Original Publish Date March 3, 2022

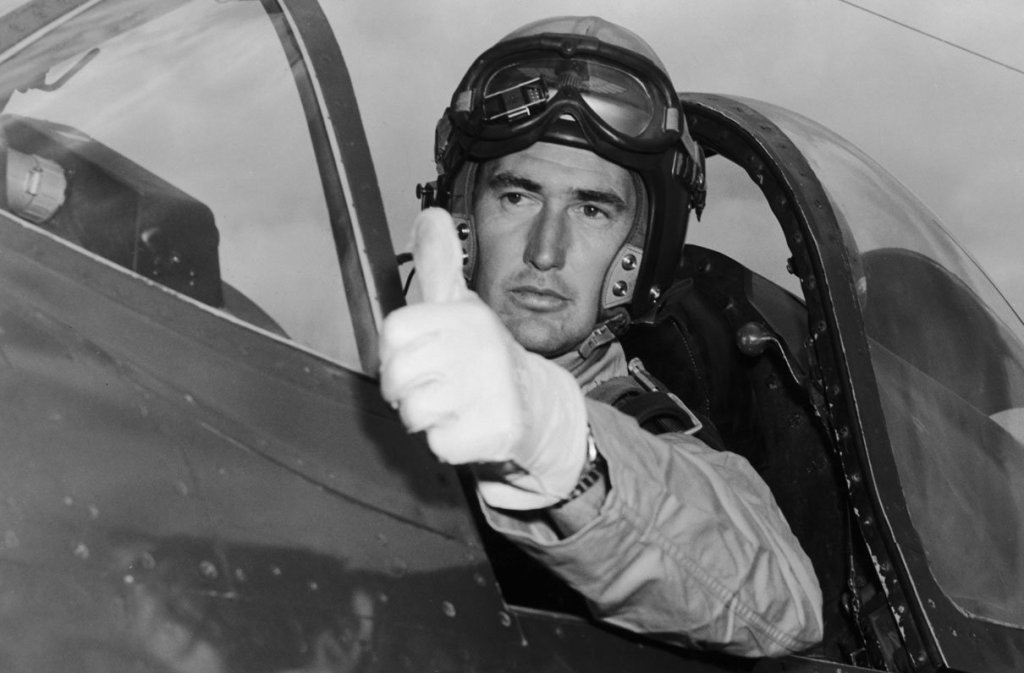

On February 16, 1953, a wounded fighter jet approached the airfield at Suwon, Korea. The plane’s radio was inoperable, its hydraulic system gone, and it was trailing smoke and bleeding fluids. Its streaming 30-foot ribbon of fire all indicated serious danger. The pilot brought his hobbled midnight-blue F9F Grumman “Panther” jet in for a dangerous wheels-up belly landing, skidding the length of the tarmac in a cloud of sparks and debris. An already tense situation became worse as the nose promptly burst into flames below the cockpit. The trapped aviator blew off the canopy, struggled out of the plane, and limped away as fire and rescue crews quickly blanketed the burning aircraft with foam. The plane was a total loss but the pilot survived.

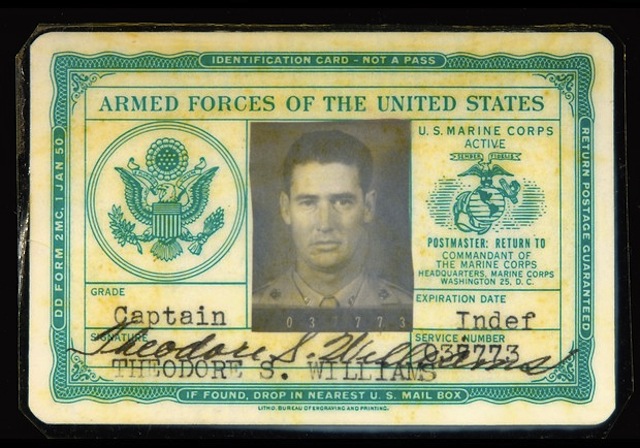

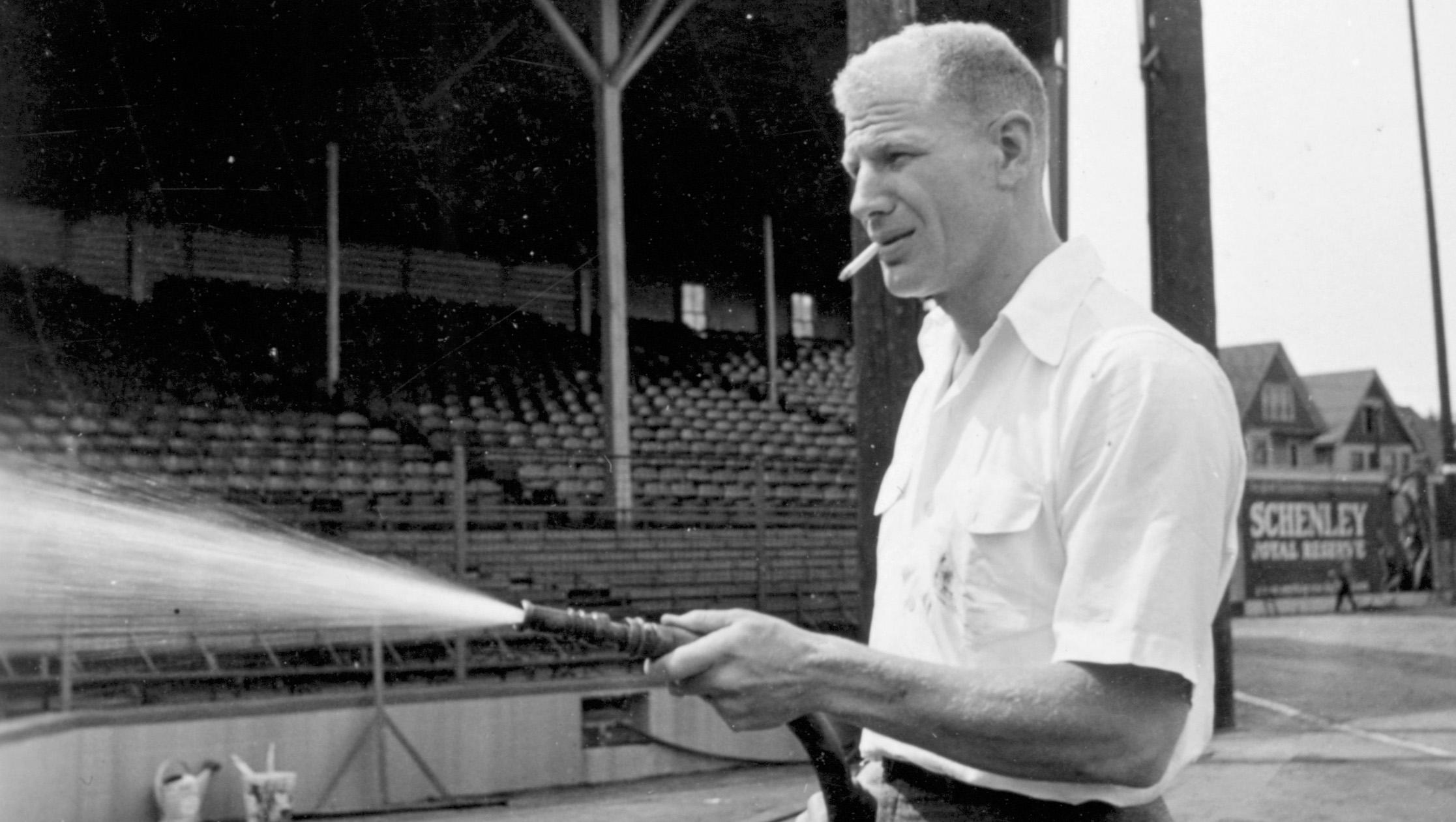

Later, the airmen at Suwon learned they had just witnessed the dramatic escape of the most famous flying leatherneck in Korea; Captain Theodore S. Williams, better known as Ted Williams of the Boston Red Sox. Williams was arguably the best baseball hitter of all time. “Teddy Ballgame” was a six-time American League batting champ, two-time AL MVP, and the last man to hit .400 for a season. He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1966 five years after hitting a homerun in his last at bat.

His stats as an airman were equally impressive. Ted flew 39 combat missions in Korea and his planes were hit by enemy fire three times. On this mission, as with many, Williams was flying as wingman for his squadron’s operations officer, John H. Glenn, Jr.: Ohio’s Mercury astronaut, former senator, and 1984 presidential candidate. Glenn and Williams were both Marine pilots during World War II but did not know each other well. Shortly after Pearl Harbor, Glenn dropped out of Muskingum College in New Concord, Ohio, and enlisted in the Marines. Williams joined the Marines at the end of the 1942 season after leading the league with a .356 batting average.

The two met and became friends in Korea. Glenn flew 63 combat missions in Korea and was nicknamed “Old Magnet Ass” because of the number of flak hits he took on low-level close air support missions. He returned to base with over 250 holes in his plane twice. But on that Feb. 16th mission, Williams’ plane was the one that took the heavy hits. When Glenn saw that his wingman’s plane was on fire, he flew to Williams’ wingtip and pointed up. The duo went up into thinner air and the fire went out.

Other pilots gestured for Williams to bail out but the slugger wouldn’t do it. Ted was 6-foot-4 and thought his knees might “catch the hatch” during ejection and that would be the end of his baseball career. Instead, Williams flew back to the base, zeroed in on the runway, and skidded to a stop. The hall of famer leaped from the cockpit and ran from the plane just as the aircraft caught fire again.

While much is known about Ted Williams the ballplayer, little is known about Williams the Marine pilot. In January 1942, Williams was drafted into the military, being put into Class 1-A (Available; fit for general military service). A friend suggested that Ted appeal his classification to the governor’s Selective Service board, since Williams was the sole support of his mother, arguing that he should be reclassified to Class 3-A (Men with dependents, not engaged in work essential to national defense). The “Splendid Splinter” was reclassified to 3-A ten days later.

Afterward, the public reaction was extremely negative. Quaker Oats stopped sponsoring Williams, and Williams, who previously had eaten Quaker products “all the time”, never ate Quaker products again. Williams took more flak by signing a new contract with the BoSox for $30,000 in 1942. That season, Williams won the Triple Crown, with a .356 batting average, 36 home runs, and 137 RBIs. On May 21, Williams hit his 100th career home run, and the next day he was sworn into the US Navy Reserves. Williams grew up in San Diego (a “Navy town”) and aviator Charles Lindbergh was one of his childhood heroes. Williams later noted that he first became interested in flying after seeing the Navy’s majestic lighter-than-air ship “Shenandoah” as a kid.

Naval aviation cadet T. S. Williams was sent to Amherst College in Massachusetts for a 90-day stint in preflight training, described as “Officer candidate school with a crash course in advanced science.” The school is where prospective pilots were whipped into shape, learned how to be military officers, and studied basic theories of how airplanes operated. Those cadets who did not wash out were then moved to Chapel Hill, N.C., for three months of preflight training. While the academic load was more strenuous, here the pilots actually got to fly airplanes. Ground-school training included subjects like engines, ordnance, aircraft characteristics, aerodynamics, and navigation.

Here the cadets flew small two-seat, single-engine, high-wing Piper NE-1 “Grasshopper” trainers to acquire the skills to fly an airplane. Next, Ted Williams was sent to the “Naval Air Station Bunker Hill” in Kokomo (Now Grissom Air Force Base) for basic flight training. There he learned more theory but also spent time flying Vultee SNV and North American SNJ trainers over the skies of Central Indiana. Upon graduation, Williams opted for the Marine Corps and moved south to Pensacola, Florida for advanced flight training as a fighter pilot.

Williams learned about tactics and weapons as he practiced advanced navigation, aerial combat maneuvering, and formation flying. His athletic ability, steady hand, and excellent eyesight made him a very good pilot. In fact, he was good enough to set the Marine gunnery record at Jacksonville. Williams once again was having an outstanding “rookie” season. Williams played on the baseball team (along with his Red Sox teammate Johnny Pesky) while in pre-flight training with the Civilian Pilot Training Course. While on the baseball team, Williams was sent back to Fenway Park on July 12, 1943, to play on an All-Star team managed by Babe Ruth. Upon meeting Williams the newspapers reported that Babe Ruth said, “Hiya, kid. You remind me a lot of myself. I love to hit. You’re one of the most natural ballplayers I’ve ever seen. And if my record is broken, I hope you’re the one to do it”. Williams later said he was “flabbergasted” by the incident, as “after all, it was Babe Ruth”. In the game, Williams hit a 425-foot home run to help give the A.L. All-Stars to a 9–8 win.

Williams went on active duty in 1943 and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the United States Marine Corps as a Naval Aviator on May 2, 1944. In mid-1944, Marine aviation in the Pacific was on the wane. Japanese fighters had all but disappeared from the skies, and the days of dogfighting fighters crisscrossing the skies over the “Solomons Slot” were gone. With fighter pilots no longer in high demand, the most promising student aviators were made flight instructors, and that is what happened to Ted Williams.

When, in the summer of 1945, Ted finally received orders for the combat zone, he was in San Francisco. On September 2, 1945, when the war ended, Second Lieutenant Theodore S. Williams USMC was in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii playing baseball in the eight-team Navy League alongside Joe DiMaggio, Joe Gordon, and Stan Musial. The Service World Series games featuring Army versus the Navy attracted crowds of 40,000. The players said it was even better than the actual World Series between the Detroit Tigers and Chicago Cubs that year.

Williams was discharged by the Marine Corps on January 28, 1946, in time to begin preparations for the upcoming baseball season. For the 1946 season, Williams hit .342 with 38 home runs and 123 RBIs. He ran away as the MVP winner and helped the Red Sox win the pennant. That season, Williams hit the only inside-the-park home run in his Major League career and topped that with the longest home run in Fenway Park history, at 502 feet (the landing zone marked by a single red seat in the Fenway bleachers).

The name Theodore S. Williams was swapped from the list of inactive reserves to active duty on January 9, 1952. As the Korean War heated up the Marines desperately needed pilots and the 33-year-old married father was one of the best. Williams returned to active duty six games into the 1952 season. After hitting a 2-run home run in his last at-bat to beat the Detroit Tigers 5-3, Williams traded his uniform for a flight suit.

Although initially bitter at being called up (he’d only been in a plane once since World War II ended), Williams realized that going to Korea was the right thing to do. Still, Williams believed his call-up had more to do with the publicity it would generate for the Marines than the true need for his services. Right before he left for Korea, the Red Sox held a “Ted Williams Day” at Fenway Park. Williams was given a Cadillac and a memory book signed by 400,000 fans. The governor of Massachusetts and the mayor of Boston were there and at the end of the ceremony, the fans in the stands held hands and sang “Auld Lang Syne” to their hero.

Williams reported to Willow Grove (Pa.) Naval Air Station for flight-refresher training and then headed to Cherry Point, N.C., for ground school before transitioning into jets. From there, Williams traveled to Pohang on Korea’s eastern coast in early 1953. Captain Williams flew 39 combat missions, sustaining heavy enemy on many occasions, and he was awarded three Air Medals before being sent home with a severe ear infection and recurring viruses in June. Williams was formally discharged from active duty on July 28, 1953, the day after a cease-fire in Korea went into effect.

Williams’ squadron commander at his North Carolina training station said of him, “He was a spoiled-brat… He had too much money and had too many people rooting for him.” Unlike Williams, Major John H. Glenn, Jr. remained in the Marines after World War II. In Korea, it would have been easy for Glenn, the operations officer in Williams’ squadron in charge of assigning pilots to their daily missions, to adopt the same attitude toward Williams but he never did.

In the early 1950s, Glenn was a hotshot Marine pilot no one outside the military had ever heard of. In the early 1950s, Williams was one of the most famous big-league players on the planet. In his 1999 memoir, Glenn described Williams as anything but a prima donna. “I had just joined the squadron and was sitting in the pilots’ ready room one day when he walked in and came over and introduced himself,” Glenn writes of their first meeting. “I had been a baseball fan since I was a boy, and meeting Ted was a thrill.”

Glenn described Williams as a pilot, “He was just great. The same skills that made him the best baseball hitter ever — the eye, the coordination, the discipline — are what he used to make himself an excellent combat pilot.” As for their shared sky duty in Korea, Glenn describes, “We would be over one of their supply roads. Then we would drop down and follow the road back toward the front, hoping to catch their troops and trucks in the open . . . We leapfrogged, with one of us flying at treetop level and the other at 1,000 or 1,500 feet above and behind in order to see farther down the road and relay advice to the `shooter’ on targets ahead. We would switch positions every 10 minutes.”

Williams later described Glenn as “Absolutely fearless. The best I ever saw. It was an honor to fly with him.” In his memoir, Glenn emphasizes his fondness for Williams and recalls how the famously zipper-thin Williams developed an appetite for the fudge Glenn’s sister-in-law would send through the mail. “Ted and I flew together a lot,” Glenn recalled, “Ted flew about half his missions as my wingman. He was a fine pilot, and I liked to fly with him.”

Williams’ two major career disruptions for military service eventually cost the slugger nearly four years of playing time at the very peak of his career. Most articles about Williams focus on his sports achievements, hardly mentioning his military service. The only question usually asked is, “Where would Ted Williams be in the record book had he not lost four prime baseball seasons serving his country?” It may be more accurate to ask, “Where would the United States be without men like Ted Williams?” Ted’s baseball achievements take a backseat to his performance as a “Flying Leatherneck.” Williams was a baseball star for nineteen years and a proud Marine for five. In the words of Senator John Glenn, “Ted may have batted .400 for the Red Sox, but he hit a thousand as a U.S. Marine.”

The train was traveling on what would have been the 101st birthday of school founder and namesake John Purdue (born October 31, 1802). Purdue, a wealthy landowner, politician, educator and merchant, was the primary benefactor of the University. In 1903, if you wanted to get to Indianapolis from either school, you had three choices: ride a horse and buggy, walk or take the train. Since these were the days before automobile travel was popular, train travel was the most widely accepted form of transportation.

The train was traveling on what would have been the 101st birthday of school founder and namesake John Purdue (born October 31, 1802). Purdue, a wealthy landowner, politician, educator and merchant, was the primary benefactor of the University. In 1903, if you wanted to get to Indianapolis from either school, you had three choices: ride a horse and buggy, walk or take the train. Since these were the days before automobile travel was popular, train travel was the most widely accepted form of transportation.

Unlike the raucous fans traveling in the 13 plush, modern streamliner train coaches behind them, the Boilermakers team traveled in relative silence, focusing on the task at hand, mentally preparing for their upcoming rivalry game in the cozy confines of an older wooden train car. Unfortunately, the athletes had no idea that a minor mistake would lead to a major disaster. Railroad protocol specified that “Special” trains operate independent of the regular schedule. Timing was everything in the railroad game.

Unlike the raucous fans traveling in the 13 plush, modern streamliner train coaches behind them, the Boilermakers team traveled in relative silence, focusing on the task at hand, mentally preparing for their upcoming rivalry game in the cozy confines of an older wooden train car. Unfortunately, the athletes had no idea that a minor mistake would lead to a major disaster. Railroad protocol specified that “Special” trains operate independent of the regular schedule. Timing was everything in the railroad game.

The Boilermakers never knew what hit ’em. The engine slammed into the coal car, splintering apart the first few cars while folding like an accordion. When the two trains collided, the lead car hit the debris, causing it to shoot into the air. This gave the full impact to the second train car, causing all the deaths. The wooden train cars splintered like kindling and were destroyed, and the adjacent cars careened violently off the elevated tracks, tumbling to the ground below like jack straws.

The Boilermakers never knew what hit ’em. The engine slammed into the coal car, splintering apart the first few cars while folding like an accordion. When the two trains collided, the lead car hit the debris, causing it to shoot into the air. This gave the full impact to the second train car, causing all the deaths. The wooden train cars splintered like kindling and were destroyed, and the adjacent cars careened violently off the elevated tracks, tumbling to the ground below like jack straws. The Indianapolis star reported, “The trains came together with a great crash, which wrecked three of the passenger coaches, in addition to the engine and tender of the special train and two or three of the coal cars. The first coach on the special train was reduced to splinters. The second coach was thrown down a fifteen-foot embankment into the gravel pit and the third coach was thrown from the track to the west-side and badly wrecked. The coal cars plowed their way into the engine and demolished it completely. The coal tender was tossed to the side and turned over. A wild effort on the part of the imprisoned passengers to escape from the wrecked car followed the crash. Immediately following the wreck the students and the others turned their attention to the work of rescuing the injured, and by the time the first ambulances arrived many of the dead and suffering young men had been carried out and placed on the grass on both sides of the track.”

The Indianapolis star reported, “The trains came together with a great crash, which wrecked three of the passenger coaches, in addition to the engine and tender of the special train and two or three of the coal cars. The first coach on the special train was reduced to splinters. The second coach was thrown down a fifteen-foot embankment into the gravel pit and the third coach was thrown from the track to the west-side and badly wrecked. The coal cars plowed their way into the engine and demolished it completely. The coal tender was tossed to the side and turned over. A wild effort on the part of the imprisoned passengers to escape from the wrecked car followed the crash. Immediately following the wreck the students and the others turned their attention to the work of rescuing the injured, and by the time the first ambulances arrived many of the dead and suffering young men had been carried out and placed on the grass on both sides of the track.” The fans at the rear of the train were unaware of what happened and only felt a slight jolt as the train came to a sudden stop. These rearmost passengers wasted no time in coming to the assistance of the victims up ahead. The erstwhile revelers skidded to a stop at the scene of carnage and were horrified at the devastation before them. Acts of unselfish action made heroes out of athletes and ordinary people alike.

The fans at the rear of the train were unaware of what happened and only felt a slight jolt as the train came to a sudden stop. These rearmost passengers wasted no time in coming to the assistance of the victims up ahead. The erstwhile revelers skidded to a stop at the scene of carnage and were horrified at the devastation before them. Acts of unselfish action made heroes out of athletes and ordinary people alike. Seventeen passengers in the first coach were killed. Thirteen of the dead were members of the Purdue football team. Walter Bailey, a reserve player from New Richmond, although grievously injured, refused aid so that others could be helped. Team Captain Skeets Leslie was covered up for dead, his body transported to the morgue with the others. It was the first catastrophe to hit a major college sports team in the history of this country. The affects would be felt for decades to come and one of those players would rise from the dead, shake off accusations of association with Irvington KKK leader D.C. Stephenson, and lead his state and country through the Great Depression.

Seventeen passengers in the first coach were killed. Thirteen of the dead were members of the Purdue football team. Walter Bailey, a reserve player from New Richmond, although grievously injured, refused aid so that others could be helped. Team Captain Skeets Leslie was covered up for dead, his body transported to the morgue with the others. It was the first catastrophe to hit a major college sports team in the history of this country. The affects would be felt for decades to come and one of those players would rise from the dead, shake off accusations of association with Irvington KKK leader D.C. Stephenson, and lead his state and country through the Great Depression.

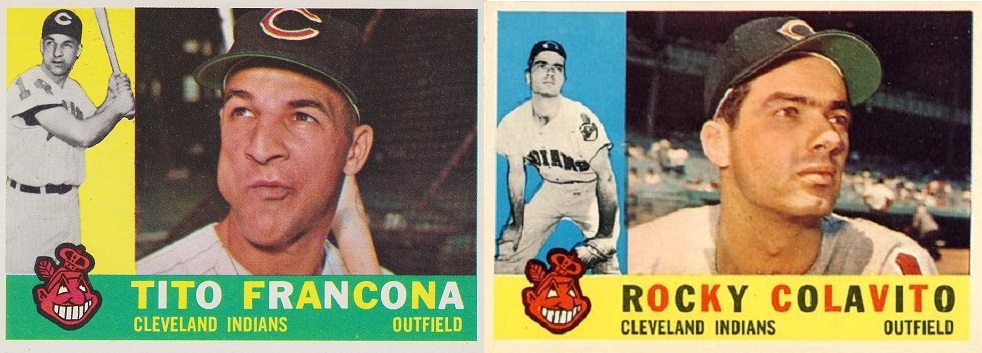

The front page of the Tucson Daily Citizen on March 27, 1961 ran a story headlined, “Practice Homer Leads To Body”. The story detailed, “An over-the-wall smash by Cleveland Indians’ Tito Francona yesterday led to the discovery that Frederick Victor Burden had carried out his threat to commit suicide after killing a man in the home of his estranged wife. Burden’s body, with a bullet in the head, was found by city parks employee John C. Cota, 52, of 238 E. E. 19th St., while he was looking for a ball that had just been knocked over the west wall during the practice at Hi Corbett Field in Randolph Park. The partially concealed body was found lying in a shallow watering trench under low – hanging palm fronds when discovered about 11:30 a m.”

The front page of the Tucson Daily Citizen on March 27, 1961 ran a story headlined, “Practice Homer Leads To Body”. The story detailed, “An over-the-wall smash by Cleveland Indians’ Tito Francona yesterday led to the discovery that Frederick Victor Burden had carried out his threat to commit suicide after killing a man in the home of his estranged wife. Burden’s body, with a bullet in the head, was found by city parks employee John C. Cota, 52, of 238 E. E. 19th St., while he was looking for a ball that had just been knocked over the west wall during the practice at Hi Corbett Field in Randolph Park. The partially concealed body was found lying in a shallow watering trench under low – hanging palm fronds when discovered about 11:30 a m.” Despite having emerged as the best defensive left fielder in the league, Francona was shifted to first base during spring training in 1962 and finished the season leading the American League in double plays turned as a first baseman. He finished with 14 homers, 28 doubles and batted .272. When Birdie Tebbetts took over as Indians manager in 1963, Francona was moved back into left, but his numbers fell drastically. His .228 batting average was a career low, and his ten home runs and 41 RBIs were his fewest over a full season. The Indians acquired All-Star Leon “Daddy Wags” Wagner to play left field prior to the 1964 season, so Francona split time between right and first base. After the season, he was dealt to the St. Louis Cardinals for a player to be named later and cash.

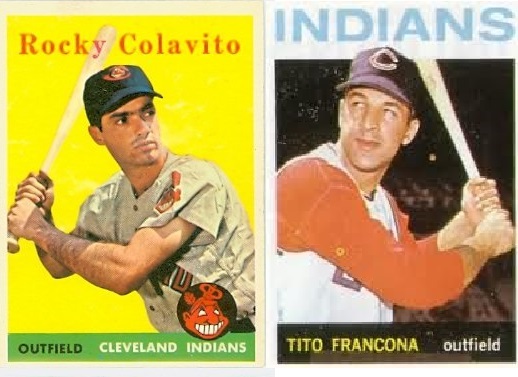

Despite having emerged as the best defensive left fielder in the league, Francona was shifted to first base during spring training in 1962 and finished the season leading the American League in double plays turned as a first baseman. He finished with 14 homers, 28 doubles and batted .272. When Birdie Tebbetts took over as Indians manager in 1963, Francona was moved back into left, but his numbers fell drastically. His .228 batting average was a career low, and his ten home runs and 41 RBIs were his fewest over a full season. The Indians acquired All-Star Leon “Daddy Wags” Wagner to play left field prior to the 1964 season, so Francona split time between right and first base. After the season, he was dealt to the St. Louis Cardinals for a player to be named later and cash. And what about that curse? The curse of Rocky Colavito? Well, in recent years, it has dampened a little with the Indians “rebuilding years” of the past two decades. But. although they’ve played in three World Series Championships since 1995, they still haven’t won one. Here are just a few of the mishaps blamed on that curse since Colavito’s 1960 trade. September 1961: Fireballer “Sudden Sam” McDowell breaks two ribs throwing a fastball. June 1964: Third Baseman Max Alvis suffers an attack of spinal meningitis on a team flight. January 1965: The Indians reacquire Rocky Colavito from the Kansas City A’s in exchange for Rookie of the Year winner Tommie Agee and future 286-game winner Tommy John. July 1970: Reds star Pete Rose plows over catcher Ray Fosse in the All-Star game, effectively ending Fosse’s career in Cleveland. June 1974: Drunken fans pour onto the Cleveland Stadium field during ten-cent beer night, forcing a forfeit while destroying the diamond. March 1977: 20-game winner Wayne Garland hurts his arm in Spring training, effectively ending his career. March 1978: Indians trade Hall of Famer Dennis Eckersley to the Red Sox. July 1981: Cleveland hosts the All-Star game which is delayed until August by the MLB strike. August 1981: 1980 AL Rookie of the Year “Super Joe” Charboneau is sent down to AAA, never to be heard of again. April 1987: Sports Illustrated picks the Indians to win the pennant but they lose 101 games and finish last. March 1993: three Indians pitchers die in car crashes and a fourth is seriously injured. July 1994: Indians are speeding towards the World Series when the season is cancelled by a player’s strike.

And what about that curse? The curse of Rocky Colavito? Well, in recent years, it has dampened a little with the Indians “rebuilding years” of the past two decades. But. although they’ve played in three World Series Championships since 1995, they still haven’t won one. Here are just a few of the mishaps blamed on that curse since Colavito’s 1960 trade. September 1961: Fireballer “Sudden Sam” McDowell breaks two ribs throwing a fastball. June 1964: Third Baseman Max Alvis suffers an attack of spinal meningitis on a team flight. January 1965: The Indians reacquire Rocky Colavito from the Kansas City A’s in exchange for Rookie of the Year winner Tommie Agee and future 286-game winner Tommy John. July 1970: Reds star Pete Rose plows over catcher Ray Fosse in the All-Star game, effectively ending Fosse’s career in Cleveland. June 1974: Drunken fans pour onto the Cleveland Stadium field during ten-cent beer night, forcing a forfeit while destroying the diamond. March 1977: 20-game winner Wayne Garland hurts his arm in Spring training, effectively ending his career. March 1978: Indians trade Hall of Famer Dennis Eckersley to the Red Sox. July 1981: Cleveland hosts the All-Star game which is delayed until August by the MLB strike. August 1981: 1980 AL Rookie of the Year “Super Joe” Charboneau is sent down to AAA, never to be heard of again. April 1987: Sports Illustrated picks the Indians to win the pennant but they lose 101 games and finish last. March 1993: three Indians pitchers die in car crashes and a fourth is seriously injured. July 1994: Indians are speeding towards the World Series when the season is cancelled by a player’s strike. There is so much about Tito Francona that typifies that which makes baseball so interesting. Aside from one of the greatest nicknames in sports history, he was considered a journeyman for most of his career, but a damned good one. Tito Francona was a baseball player, a great husband and father and an even better teammate. When he died at the age of 84 he left a lasting legacy. Tito was there at the beginning of “The Curse” and although he’s gone, he’s likely to be there when the curse ends because “Little Tito” just might lead the Indians to a World Series Championship this season. After all, it was Francona who broke the Boston Red Sox Curse of Babe Ruth by winning two World’s Series titles in four years. Yep, baseball is a funny game.

There is so much about Tito Francona that typifies that which makes baseball so interesting. Aside from one of the greatest nicknames in sports history, he was considered a journeyman for most of his career, but a damned good one. Tito Francona was a baseball player, a great husband and father and an even better teammate. When he died at the age of 84 he left a lasting legacy. Tito was there at the beginning of “The Curse” and although he’s gone, he’s likely to be there when the curse ends because “Little Tito” just might lead the Indians to a World Series Championship this season. After all, it was Francona who broke the Boston Red Sox Curse of Babe Ruth by winning two World’s Series titles in four years. Yep, baseball is a funny game.

My grandparents retired to Cape Coral in the late 1970s and I recall one of their oldster neighbors showing me a photo album from the 1930s with pictures of the New York Yankees at Spring Training down there. Turns out his family lived near the facility, Fort Lauderdale if memory serves, where the Yankees trained. I can remember the photos in there of Lou Gehrig in a bathing suit (MAN that dude was HUGE!) and Babe Ruth in full uniform on the beach, two bats resting on his shoulder with his fielder’s glove and cleats hanging from the back like a hobo pouch. In his pin striped uniform! On the Beach! Everything in that photo would be worth a small fortune today, including the photo itself!

My grandparents retired to Cape Coral in the late 1970s and I recall one of their oldster neighbors showing me a photo album from the 1930s with pictures of the New York Yankees at Spring Training down there. Turns out his family lived near the facility, Fort Lauderdale if memory serves, where the Yankees trained. I can remember the photos in there of Lou Gehrig in a bathing suit (MAN that dude was HUGE!) and Babe Ruth in full uniform on the beach, two bats resting on his shoulder with his fielder’s glove and cleats hanging from the back like a hobo pouch. In his pin striped uniform! On the Beach! Everything in that photo would be worth a small fortune today, including the photo itself! Somehow, I became a Blue Jays fan. Probably because I went to their first spring training game in franchise history in Dunedin. March 11, 1977 they beat the Mets 3-1 at Grant Field, which was built in 1930 and looked like it. I went to a few games that year. I distinctly recall sitting on a wooden bleacher seat right next to Tom Seaver who was talking to me like it was no big deal. And he was pitching that day. Within a few weeks, he was traded to the Cincinnati Reds “Big Red Machine.” Florida meant Spring Training, period. Somewhere along the line that changed.

Somehow, I became a Blue Jays fan. Probably because I went to their first spring training game in franchise history in Dunedin. March 11, 1977 they beat the Mets 3-1 at Grant Field, which was built in 1930 and looked like it. I went to a few games that year. I distinctly recall sitting on a wooden bleacher seat right next to Tom Seaver who was talking to me like it was no big deal. And he was pitching that day. Within a few weeks, he was traded to the Cincinnati Reds “Big Red Machine.” Florida meant Spring Training, period. Somewhere along the line that changed. March of 1961 was a busy time: America’s brand new President John F. Kennedy creates the Peace Corps, The Beatles start performing at the Cavern Club, Nine African-American students from Mississippi’s Tougaloo College made the first peaceful attempt to end segregation by staging a “read-in” at the whites-only main branch of the Jackson municipal public library, NASA launches a Mercury-Redstone BD rocket from Cape Canaveral as one final test flight to certify its safety for human transport. Alan Shepard had volunteered to take the flight and become the first man to travel into outer space, but was stopped by Wernher von Braun from going, Less than three weeks later, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin would, on April 12, would reach the milestone, Actor Ronald Reagan bursts onto the political scene with his speech “Encroaching Control” before the Phoenix chamber of commerce and the Boston Strangler Albert DeSalvo is captured.

March of 1961 was a busy time: America’s brand new President John F. Kennedy creates the Peace Corps, The Beatles start performing at the Cavern Club, Nine African-American students from Mississippi’s Tougaloo College made the first peaceful attempt to end segregation by staging a “read-in” at the whites-only main branch of the Jackson municipal public library, NASA launches a Mercury-Redstone BD rocket from Cape Canaveral as one final test flight to certify its safety for human transport. Alan Shepard had volunteered to take the flight and become the first man to travel into outer space, but was stopped by Wernher von Braun from going, Less than three weeks later, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin would, on April 12, would reach the milestone, Actor Ronald Reagan bursts onto the political scene with his speech “Encroaching Control” before the Phoenix chamber of commerce and the Boston Strangler Albert DeSalvo is captured.

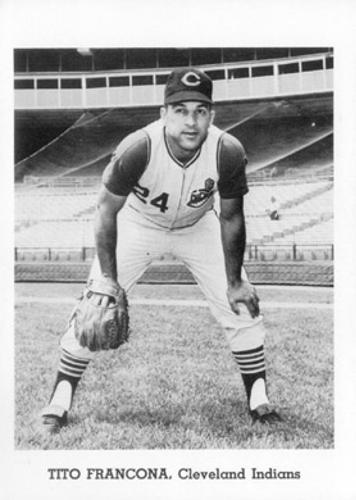

Last year, John Patsy Francona, a Cleveland Indians fan favorite better known as “Tito” died on the eve of spring training. It was the day before Valentine’s Day and the Indians’ pitchers & catchers were just trickling in to their spring training park in Goodyear, Arizona. The passing was made all the more bittersweet when you consider that the team was managed by Tito’s son, Terry Francona. Terry grew up in the Indians dugout where players called him “Little Tito.” As a member of the Montreal Expos, Terry played against our Indians here in Indianapolis at the old 16th street stadium. Before that he played college ball for Arizona State and led his team to the 1980 College World Series Championship. Terry Francona’s dad’s nickname of “Tito” was naturally passed down to his son, and although the broadcasters and news media still call him “Terry”, Tito is what the manager’s friends and players call him.

Last year, John Patsy Francona, a Cleveland Indians fan favorite better known as “Tito” died on the eve of spring training. It was the day before Valentine’s Day and the Indians’ pitchers & catchers were just trickling in to their spring training park in Goodyear, Arizona. The passing was made all the more bittersweet when you consider that the team was managed by Tito’s son, Terry Francona. Terry grew up in the Indians dugout where players called him “Little Tito.” As a member of the Montreal Expos, Terry played against our Indians here in Indianapolis at the old 16th street stadium. Before that he played college ball for Arizona State and led his team to the 1980 College World Series Championship. Terry Francona’s dad’s nickname of “Tito” was naturally passed down to his son, and although the broadcasters and news media still call him “Terry”, Tito is what the manager’s friends and players call him. That season Tito batted .363 with a career high twenty home runs and 79 RBIs to help the Indians to an 89–65 record and second place in the American League. His .363 average would have led the league, however, he fell 34 at-bats short of the 3.1 per game necessary to qualify. The batting championship went to the Detroit Tigers’ Harvey Kuenn, with a .353 batting average, ten points below Tito. Francona finished fifth in balloting for the AL Most Valuable Player Award that season. He compiled 20 home runs, 17 doubles, 79 RBIs, 68 runs scored, 145 hits, a .414 on-base percentage and a .566 slugging percentage in 122 games.

That season Tito batted .363 with a career high twenty home runs and 79 RBIs to help the Indians to an 89–65 record and second place in the American League. His .363 average would have led the league, however, he fell 34 at-bats short of the 3.1 per game necessary to qualify. The batting championship went to the Detroit Tigers’ Harvey Kuenn, with a .353 batting average, ten points below Tito. Francona finished fifth in balloting for the AL Most Valuable Player Award that season. He compiled 20 home runs, 17 doubles, 79 RBIs, 68 runs scored, 145 hits, a .414 on-base percentage and a .566 slugging percentage in 122 games.