Original publish date: February 28, 2019

It would be harder to find a more quintessential Victorian Era Englishman than Oscar Wilde, especially if you were to ask a literate American. Who was Oscar Wilde you ask? Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills Wilde (October 16,1854-November 30, 1900) was THE flamboyant Irish poet and playwright. He became one of London’s most popular playwrights in the early 1890s and is perhaps best remembered for his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, and the peculiar circumstances of his imprisonment and early death. What is largely forgotten is his visit to America in 1882, including two stops in the Hoosier state.

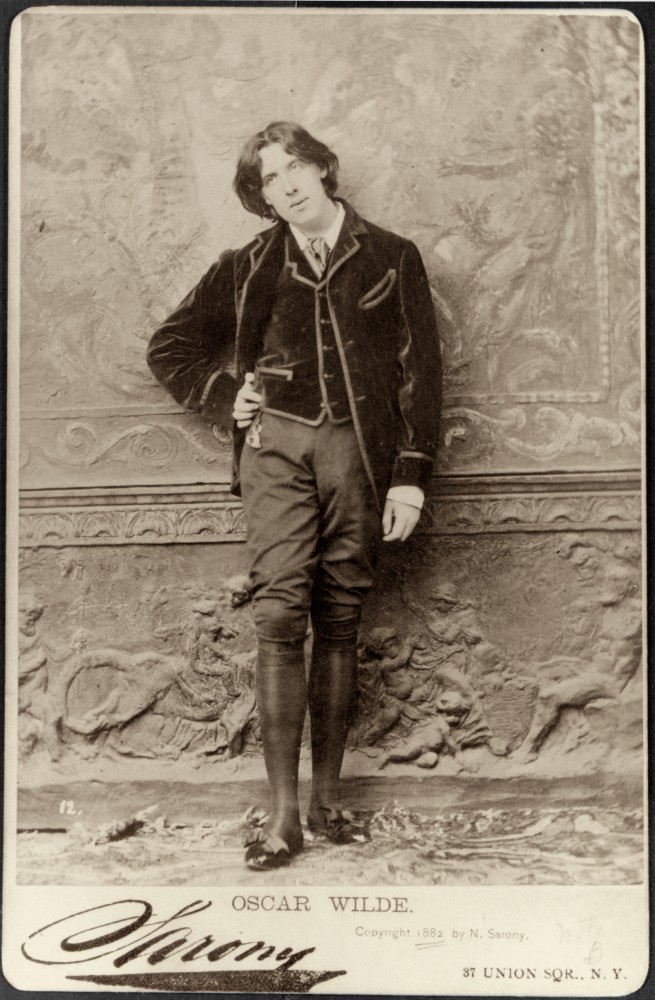

On January 3, 1882, 27-year-old Oscar Wilde arrived in New York on what would become a year long 15,000 mile visit to 150 American cities. The Dublin-born Oxford educated man was at the pinnacle of his personal eccentricity. His garish fashion sense, acerbic wit, and extravagant passion for art and home design had made such a spectacle in London that none other than Gilbert & Sullivan penned an operetta named “Patience” that lampooned Wilde as the champion of England’s aesthetic movement of the 1870s and ’80s . He was hired to go to America to lecture on interior decorating but in the end, it turned out to be a way for Wilde to promote himself. His visit may well have been one of the very first examples of “branding” as we know it today. It was on this lecture tour where most of the iconic photographic images so associated with Wilde and his “fierce” fashion sense were made.

Despite the fact that at the time of his visit, Wilde was only the author of one self-published book of poems and a single unproduced play, he often proclaimed himself a “star”. His established routine was to appear on stage dressed in satin breeches and a velvet coat with lace trim crowned by a velvet feathered slouch hat perched at a jaunty angle as he advocated the importance of sconces and embroidered pillows—and himself. Wilde was among the first “celebrity” to understand that fame for it’s own sake could launch a career and sustain one. Good or bad, no matter, Wilde’s only concern what that they spell his name right.

According to biographer David M. Friedman (Wilde in America) Widle’s tour of nineteenth-century America ranged “from the mansions of Gilded Age Manhattan to roller-skating rinks in Indiana, from an opium den in San Francisco to the bottom of the Matchless silver mine in Colorado—then the richest on earth—where Wilde dined with twelve gobsmacked miners, later describing their feast to his friends in London as “First course: whiskey. Second course: whiskey. Third course: whiskey.” Wilde gave 100 interviews in America, more than anyone else in the world in 1882. Wilde arrived in an America whose news headlines were populated by outlaws (Jesse James), Presidential assassins (Charles Guiteau), legendary showmen (P.T. Barnum), and inventors (Thomas Edison). Where grabbing headlines are concerned, Oscar Wilde went toe-to-toe with them all. The difference being that Oscar Wilde was the first to become famous for being famous.

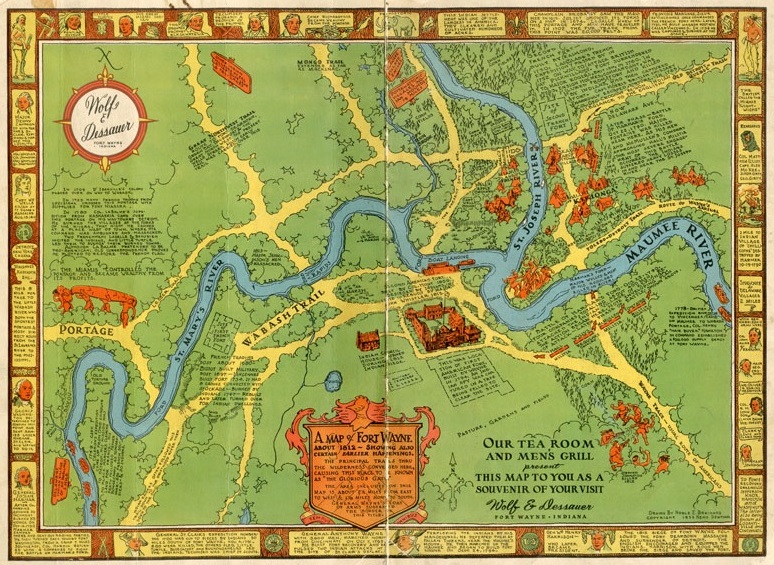

The first stop in Indiana on Wilde’s tour came in Fort Wayne on February 16, 1882. Wilde appeared at a facility known as “The Rink” located at 215 East Berry St. in the city (between Clinton and Barr streets). As the name denotes, it was opened as a rollerskating rink in 1869 and was converted into a public house known as “The Academy of Music” for the next decade before it became “The People’s Theatre” before being demolished in 1901. According to the “Pictorial History of Fort Wayne” the building stood on the site of the present Lincoln Memorial Life Insurance Building and was 60 feet wide by 150 feet long with a floor space capable of accommodating 500 ice skaters.

The Fort Wayne daily Gazette reported, “the Academy was about three quarters filled last night to hear Oscar Wilde, the greatly advertised lecturer, who has carried with him the lovers of the beautiful and his ideas of art. His lecture, in the main, is certainly an elaborately written, beautifully worded piece of literature; but for Oscar Wilde he is not an elocutionist, his voice is as effeminate as a school girl’s, and he becomes very tiresome to his auditors, even those who admire the lily and sunflower theory of the aesthetic genius. That Oscar Wilde is a cultured man no one will deny, that he is an orator, every one will hold up their hands in horror against such an insinuation.” The Fort Wayne News called the talk a “languid, monotonous stream of mechanically arranged words … scholarly but pointless; as instructive as a tax list to a pauper, and scarcely as interesting.” From Fort Wayne, Wilde circled around to Detroit, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Louisville, and Indianapolis.

Wilde’s February visit to Indianapolis came at a busy time in the city with 3 major conventions taking place: A veterans of the Mexican War reunion, the GAR reunion of Civil War Vets and the Greenback Party convention. Wilde appeared in person for one of his fashion lectures at the English Opera House on the northwest quadrant Monument Circle on February 22, 1882. A full color poster inside the opera house’s marble entryway declared that Wilde’s visit would be “The Fashionable event of the season.” The building was constructed by the Honorable William H. English, a businessman, banker, historian, and politician. Opened on September 20, 1880, the English immediately became the city’s leading theatre and remained so for the next 68 years. Widle’s visit came two years after Hancock ran for Vice-President with Civil War Hero of Gettysburg, General Winfield Scott Hancock.

A crowd of 500 people crowded the opera house to witness Wilde’s 75 minute performance titled “The Decorative Arts”. The Feb. 23, 1883 issue of the Indianapolis News reported, “Oscar Wilde delivered his lecture on “The English Renaissance” last evening at English’s Opera House, to a large audience. He appeared half an hour late, and was greeted with a tender murmur of applause. He came upon the stage alone and proceeded to his lecture without formal introduction. He was dressed partly in the style made familiar to most of his hearers by “Grosvernor” in “Patience.” He wore a dress coat, double-breasted white vest, exposing a wide expanse of unsullied shirt front, in the middle of which glowed a single stud of gold, a standing collar, dead white silk necktie most artistically knotted, knee breeches, black silk stockings and low-cut shoes… Mr. Wilde has been has been variously criticized, but all agree that he is well worth seeing and listening to. Some can make nothing out of his lecture while others are delighted with it. The only way to judge is for each to go and hear for yourself.”

No less than five separate newspaper columns excoriated Wilde or his performance. The Indianapolis Journal newspaper said “We have grown sunflowers for many a year, suddenly, we are told there is a beauty in them our eyes have never been able to see. And hundreds of youths are smitten with the love of the helianthus. Alackaday! We must have our farces and our clowns. What fool next?” Soon, gaggles of admiring young men sporting sunflowers in their velvet lapels formed clubs known as “sunflower boys” to sit front and center at Wilde’s appearances. At Wilde’s other appearances, so many young street toughs interrupted Wilde’s shows that he sent advance notice to Denver that he would no longer act the gentleman and that he was “practicing with my new revolver by shooting at sparrows on telegraph wires from my car. My aim is as lethal as lighting. — O. Wilde.”

No less than five separate newspaper columns excoriated Wilde or his performance. The Indianapolis Journal newspaper said “We have grown sunflowers for many a year, suddenly, we are told there is a beauty in them our eyes have never been able to see. And hundreds of youths are smitten with the love of the helianthus. Alackaday! We must have our farces and our clowns. What fool next?” Soon, gaggles of admiring young men sporting sunflowers in their velvet lapels formed clubs known as “sunflower boys” to sit front and center at Wilde’s appearances. At Wilde’s other appearances, so many young street toughs interrupted Wilde’s shows that he sent advance notice to Denver that he would no longer act the gentleman and that he was “practicing with my new revolver by shooting at sparrows on telegraph wires from my car. My aim is as lethal as lighting. — O. Wilde.”

“He knows uncommonly well what he is doing,” said the Indianapolis News. The Indianapolis Daily Sentinel reported that “from pit to dome,” most came to make fun of him, but many soon realized that he had something to say. “It would be safe to wage a cigar that if Oscar can be induced by his manager to be a little more utilitarian, he will not want for appreciate or applause.” Wilde took the conservative criticism seriously and decided to tone down his outlandish stage costumes. Wilde later noted that his next night’s audience was “dreadfully disappointed at Cincinnati at my not wearing knee breeches.” Of the Queen City, Wilde quipped, “I wonder that no criminal has ever pleaded the ugliness of your city as an excuse for his crimes.”

Morris Ross, one of the “legendary foursome” staff of writers and editors for the Indianapolis News (including Hilton U. Brown, Meredith Nicholson and Louis Howland), said that Wilde gained attention “mainly by adopting knee breeches and a lily. The latter’s lecture at the last-named city was by no means successful. One reporter caught him using the word “handicrawftsmen” seventeen times and noted his pronunciation of “teel-e-phone,” “eye-solate,” and “vawse.” The same newsman disliked Wilde’s legs, which he said had no more symmetry than the same length of garden hose. Wilde was invited to the governor’s party that evening and on the way he was asked why he came to America. “For recreation and pleasure,” he answered with his typical wit, “but I have not, as yet, found any Americans. There are English, French, Danes, and Spaniards in New York; but I have yet to see an American.” This was a common British criticism of this country during the nineteenth century. At dinner with the governor and his family, Wilde ate greedily. The Saturday Review reported that when he was introduced to ice cream he spooned it up “with the languor of a debilitated duck.”29 Indiana of the 1880’s was truly unsympathetic to Wilde and the aesthetic movement.”

Morris Ross, one of the “legendary foursome” staff of writers and editors for the Indianapolis News (including Hilton U. Brown, Meredith Nicholson and Louis Howland), said that Wilde gained attention “mainly by adopting knee breeches and a lily. The latter’s lecture at the last-named city was by no means successful. One reporter caught him using the word “handicrawftsmen” seventeen times and noted his pronunciation of “teel-e-phone,” “eye-solate,” and “vawse.” The same newsman disliked Wilde’s legs, which he said had no more symmetry than the same length of garden hose. Wilde was invited to the governor’s party that evening and on the way he was asked why he came to America. “For recreation and pleasure,” he answered with his typical wit, “but I have not, as yet, found any Americans. There are English, French, Danes, and Spaniards in New York; but I have yet to see an American.” This was a common British criticism of this country during the nineteenth century. At dinner with the governor and his family, Wilde ate greedily. The Saturday Review reported that when he was introduced to ice cream he spooned it up “with the languor of a debilitated duck.”29 Indiana of the 1880’s was truly unsympathetic to Wilde and the aesthetic movement.”

On his 1882 lecture tour of America drank elderberry wine with Walt Whitman in Camden (of whom he said, “I have the kiss of Walt Whitman still on my lips.”), conversed chillily with Henry James in Washington (who called Wilde “the most gruesome object I ever saw”), lectured in Saint Joseph, Missouri (two weeks after the death of Jesse James), called on an elderly Jefferson Davis at his Mississippi plantation (of whom Wilde inexplicably remarked, “The principles for which Jefferson Davis and the South went to war cannot suffer defeat.”), and fell prey to a con-man in New York’s Tenderloin (he lost $ 5,000 to legendary Gotham City conman Hungry Joe Lewis in a rigged Bunco game).

On his 1882 lecture tour of America drank elderberry wine with Walt Whitman in Camden (of whom he said, “I have the kiss of Walt Whitman still on my lips.”), conversed chillily with Henry James in Washington (who called Wilde “the most gruesome object I ever saw”), lectured in Saint Joseph, Missouri (two weeks after the death of Jesse James), called on an elderly Jefferson Davis at his Mississippi plantation (of whom Wilde inexplicably remarked, “The principles for which Jefferson Davis and the South went to war cannot suffer defeat.”), and fell prey to a con-man in New York’s Tenderloin (he lost $ 5,000 to legendary Gotham City conman Hungry Joe Lewis in a rigged Bunco game).

However, my favorite encounter story from Wilde’s American tour comes from his visit to Hildene. the New Hampshire estate of President Abraham Lincoln’s son Robert Todd Lincoln. Wilde ate dinner with the former Secretary of War and his wife Mary. Mrs. Lincoln was apparently entranced by Wilde but Robert remained silent throughout the encounter. The visit culminated with Mr. Lincoln’s sudden rise and push back from the table followed by a slamming of his napkin onto his dinner plate and announcement, “I do not care for that man!” Years after Lincoln’s death in 1926, an imperial sized cabinet photo of Wilde (dressed in all his finery) was found in the Secretary’s estate signed “To Robert T. Lincoln, with my very best wishes, Oscar Wilde”. Oh, if they only knew.

I asked Mr. Casteel if it was true that Longstreet’s granddaughter attended the unveiling ceremony. He answered quickly, “Oh yes. Jamie Longstreet Paterson attended the dedication ceremony. We brought out a ladder and she climbed up to get a better look at the General. I was worried because she was 67-years-old but more worried when she started to cry,” said Gary. “I thought, oh my, we may have a problem here. When she came down, I realized they were tears of joy as she said, ‘I never thought I would look him in the face’.” Sculptor Casteel’s Longstreet memorial was one of the last monuments erected at the Gettysburg National Military Park. It was dedicated on July 3, 1998, the 135th anniversary of the end of the battle of Gettysburg. Jamie Paterson Longstreet died six years later on August 4, 2014.

I asked Mr. Casteel if it was true that Longstreet’s granddaughter attended the unveiling ceremony. He answered quickly, “Oh yes. Jamie Longstreet Paterson attended the dedication ceremony. We brought out a ladder and she climbed up to get a better look at the General. I was worried because she was 67-years-old but more worried when she started to cry,” said Gary. “I thought, oh my, we may have a problem here. When she came down, I realized they were tears of joy as she said, ‘I never thought I would look him in the face’.” Sculptor Casteel’s Longstreet memorial was one of the last monuments erected at the Gettysburg National Military Park. It was dedicated on July 3, 1998, the 135th anniversary of the end of the battle of Gettysburg. Jamie Paterson Longstreet died six years later on August 4, 2014. It should be noted that Casteel is not only an accomplished sculptor, knowledgeable historian and well versed art scholar, he has deeper personal roots in the Civil War and Battle of Gettysburg itself. Casteel says that his own family had two ancestors -brothers in fact- who actually fired at each other from opposing sides during the Battle of Gettysburg. “I call him Uncle Bill and he placed his rifle against that stone wall and fired our way from right over there” as he points out his studio window. Casteel is currently hard at work on several pieces for the proposed National Civil War Memorial. “Did you realize that there is no national monument to the Civil War?” he asks.

It should be noted that Casteel is not only an accomplished sculptor, knowledgeable historian and well versed art scholar, he has deeper personal roots in the Civil War and Battle of Gettysburg itself. Casteel says that his own family had two ancestors -brothers in fact- who actually fired at each other from opposing sides during the Battle of Gettysburg. “I call him Uncle Bill and he placed his rifle against that stone wall and fired our way from right over there” as he points out his studio window. Casteel is currently hard at work on several pieces for the proposed National Civil War Memorial. “Did you realize that there is no national monument to the Civil War?” he asks.

Gary guides us to a loose leaf binder containing images of the large sculpture medallions he has created for the museum. Lincoln, Lee, Jefferson Davis, and John Wilkes Booth are just a few of the completed images resting on the drying racks in the back of Gary’s studio. Gary remarks, “I asked Ed Bearss (Chief Historian Emeritus of the National Park Service), who serves on the museum board, why there was no plaque for Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain (Hero of Gettysburg’s Little Round Top) in the selection. He responded, ‘Gary, no one ever heard of Chamberlain before Gettysburg or afterwards for that matter.” Yes, talking with Gary Casteel gives new perspective to an old subject and promises to make a visit to his studio an unforgettable memory.

Gary guides us to a loose leaf binder containing images of the large sculpture medallions he has created for the museum. Lincoln, Lee, Jefferson Davis, and John Wilkes Booth are just a few of the completed images resting on the drying racks in the back of Gary’s studio. Gary remarks, “I asked Ed Bearss (Chief Historian Emeritus of the National Park Service), who serves on the museum board, why there was no plaque for Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain (Hero of Gettysburg’s Little Round Top) in the selection. He responded, ‘Gary, no one ever heard of Chamberlain before Gettysburg or afterwards for that matter.” Yes, talking with Gary Casteel gives new perspective to an old subject and promises to make a visit to his studio an unforgettable memory.