PLEASE SHARE!

February 5, 2023.

Friends, please consider joining me in a project celebrating the 99th birthday of the Dean of all Abraham Lincoln scholars from Springfield, Illinois:

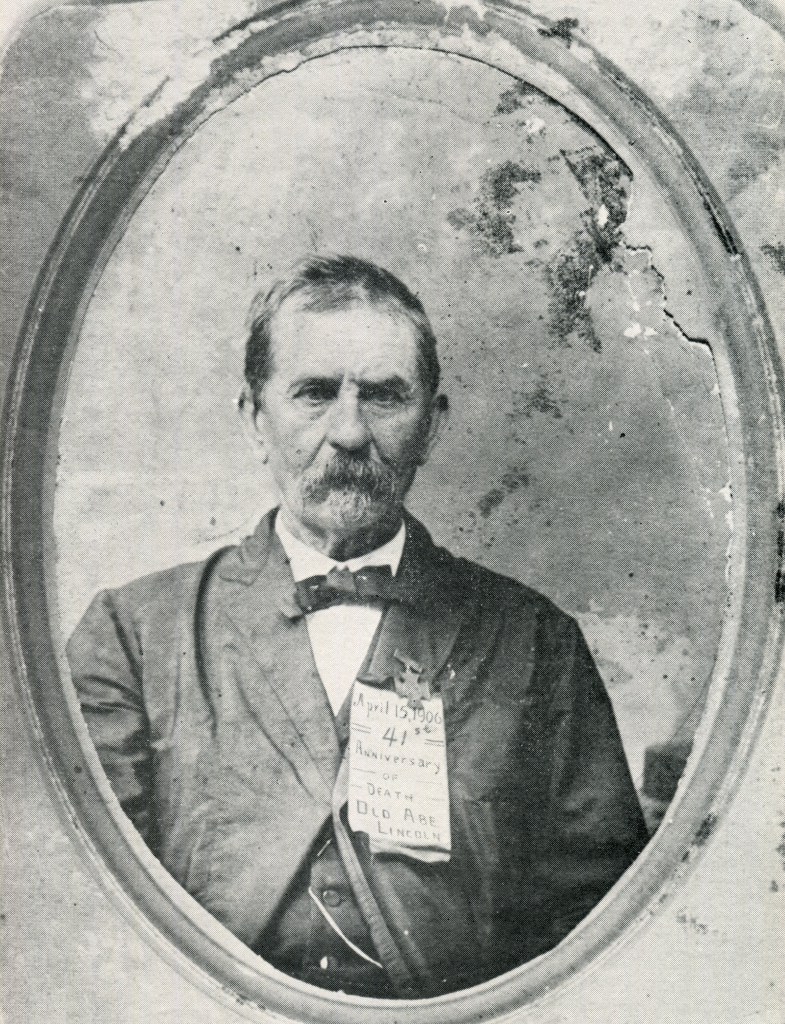

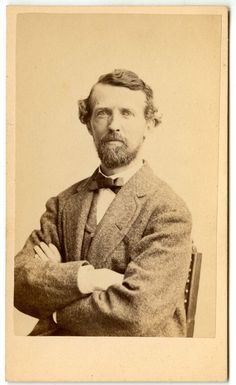

Dr. Wayne C. “Doc” Temple.

I have been working on a biography of Doc for some time now. For nearly 70 years, Doc has researched, written, and published more than 20 books and over 300 articles on Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War, Indigenous tribes, and Midwest history. Along the way, Doc has graciously volunteered his time, knowledge & wisdom with countless students and scholars along the way. Most of today’s Lincoln scholars have consulted Doc for facts in their work.

This will be Doc’s first birthday since losing Sandy, his wife of 42 years, last March. Doc is a member of America’s greatest generation having fought bravely for the United States in the European theatre, once actually standing in an open road firing a Thompson Sub-machine gun at a German fighter plane strafing his unit. He is an amazing man.

I ask that you join me in sending a birthday card or friendly note to Doc (he doesn’t do e-mail) in time for his 99th birthday (February 5, 2023) in care of the address below. Please share this humble announcement to your page and we’ll see if we can’t get 99 cards for Doc’s 99th birthday. His personal archives will be donated to the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield and these birthday cards will be preserved among that collection. Thank you for your consideration.

Wayne “Doc” Temple

c/o Books on the Square

427 East Washington Street

Springfield, IL 62701

————–

Doc’s historical resume is unchallenged. In my opinion, he is our nation’s greatest living Lincoln scholar. I am just one of the legion of Lincoln scholars he has helped and encouraged along the way. Doc served as chief deputy director of the Illinois State Archives for over 50 years (1964-2016), Secretary-treasurer of the National Lincoln-Civil War Council during the 100th anniversary Centennial years (1958-1964), and editor / associate of the Lincoln Herald since 1973.

I have listed Doc’s “resume” below. As you can see, it is quite impressive.

Doc’s education credentials & historical resume:

AB cum laude, University of Illinois, 1949; AM, University of Illinois, 1951; Doctor of Philosophy, University of Illinois, 1956; Lincoln Diploma of Honor (Illinois’ highest civilian award), Dean of history at Lincoln Memorial U., Harrogate, Tennessee, 1963. Wayne Calhoun Temple has been listed as a noteworthy Historian by Marquis Who’s Who.

Curator ethnohistory, Illinois State Museum, 1954-1958; editor-in-chief, Lincoln Herald, Lincoln Memorial U., 1958-1973; associate editor, Lincoln Herald, Lincoln Memorial U., since 1973; also director department Lincolniana, director university press, John Wingate Weeks professor of history, Lincoln Herald, Lincoln Memorial U., 1958-1964; with, Illinois State Archives, since 1964; chief deputy director, Illinois State Archives. Lecturer United States Military Academy, 1975. Secretary-treasurer National Lincoln-Civil War Council, 1958-1964.

Member bibliography committee Lincoln Lore, since 1958. Honorary member Lincoln Sesquicentennial Commission, 1959-1960. Advisory council United States Civil War Centennial Commission, 1960-1966.

Major Civil War Press Corps, since 1962. President Midwest Conference Masonic Education, 1985.

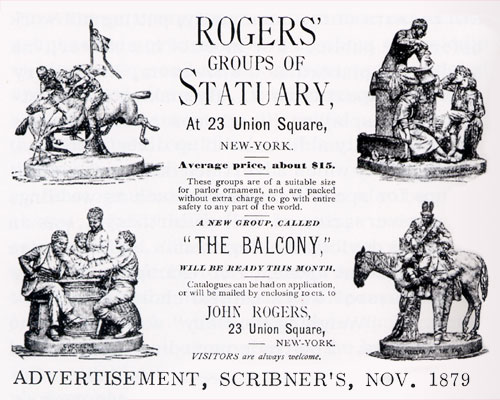

Doc’s books include:

Lincoln the Railsplitter 1961. (listed in the top 100 Lincoln books ever written)

Stephen A. Douglas, freemason Stephen A. Douglas, Freemason.

Abraham Lincoln and Others at the St. Nicholas.

Lincoln’s Confidant: The Life of Noah Brooks (The Knox College Lincoln Studies Center) by Wayne C. Temple, Douglas L. Wilson, et al. / Nov 30, 2018

Abraham Lincoln: From Skeptic to Prophet 1st Edition by Wayne C. Temple (1995)

Alexander Williamson: Friend of the Lincolns (Special publication)

Lincoln’s Surgeons at His Assassination Hardcover – October 29, 2015

BY SQUARE AND COMPASS: THE BUILDING OF LINCOLN’S HOME AND ITS SAGA.

Lincoln-Grant: Illinois militiamen Lincoln-Grant: Illinois militiamen

Indian Villages of the Illinois Country: Historic Tribes (Scientific Papers, Vol 2, Pt 2)

Membership:

Sponsor Abraham Lincoln Bay, Washington National Cathedral. Member Illinois State Flag Commission, since 1969. Trustee, regent Lincoln Academy Illinois, 1970-1982, Bicentennial Order Lincoln, 2009.

Board governors St. Louis unit Shriners Hospitals for Crippled Children, 1975-1981. Commissioning committee, honorary crew member and plank owner United States Ship Springfield submarine, since 1990. Honorary crew member United States Ship Abraham Lincoln aircraft carrier, since 1989.

With United States Army, 1943-1946, general Reserve (retired). Fellow Royal Society Arts (life). Member National Rifle Association, Knight Templar (Red Cross Constantine), Lincoln Group District of Columbia (honorary), University Illinois Alumni Association, Illinois State History Society, Board of Advisors, The Lincoln Forum, Illinois Professional Land Surveyors Association, Illinois State Dental Society (citation plague 1966), Reserve Officers Association, Lincoln Fellowship of Wisconsin, Iron Brigade Association (honorary life), Military Order Loyal Legion United States (honorary companion), Military Order Foreign Wars United States, Army and Navy Union, Masons (33 degree, Meritorious Service award, grand representative from Grand Lodge of Colorado), Shriners, Kappa Delta Pi, Phi Alpha, Phi Alpha Theta (Scholarship Key award), Chi Gamma Iota, Phi Beta Kappa, Tau Kappa Alpha, Alpha Psi Omega, Sigma Pi Beta (Headmaster), Sigma Tau Delta (Gold Honor Key award for editorial writing), Zeta Psi.

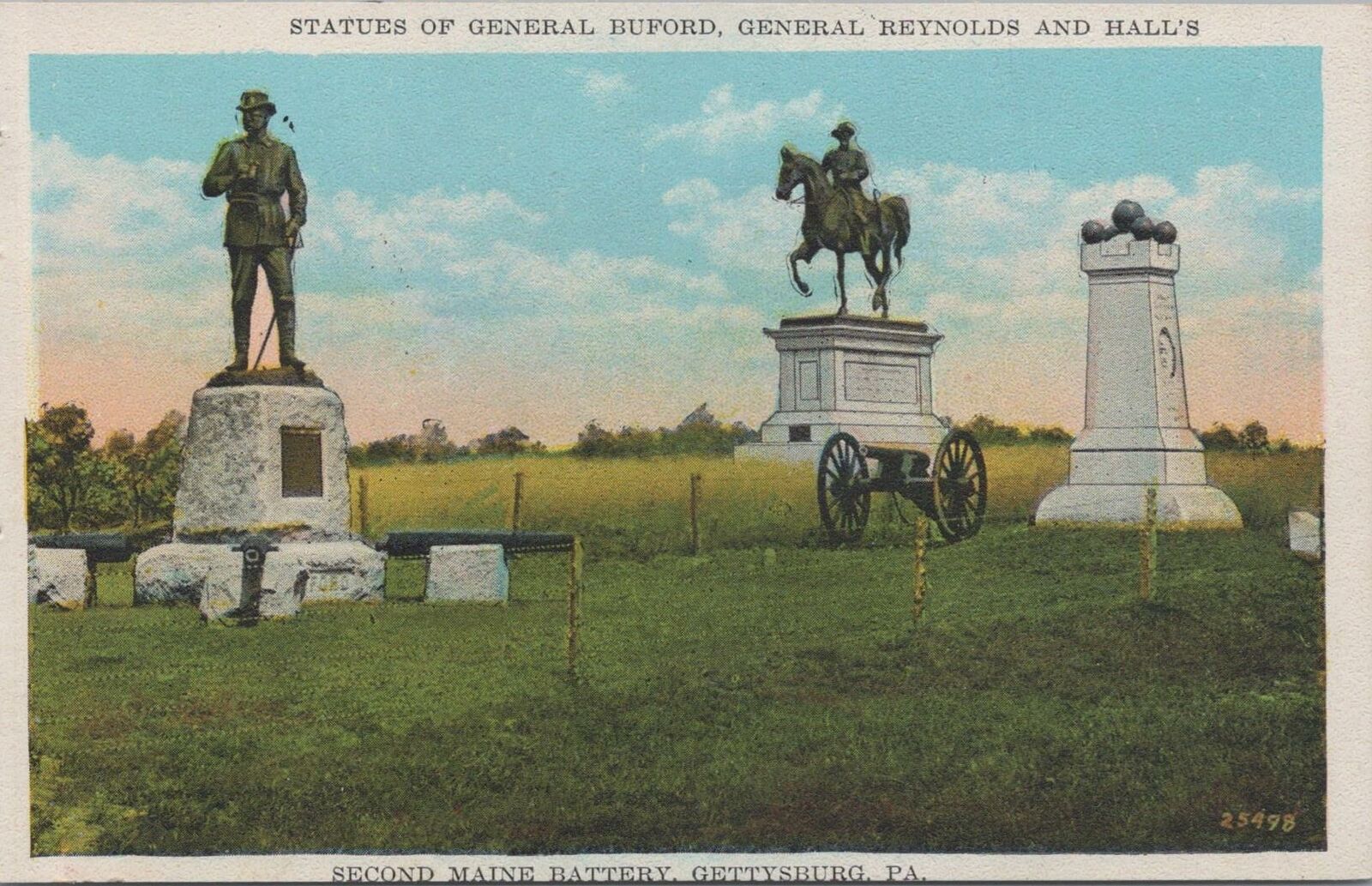

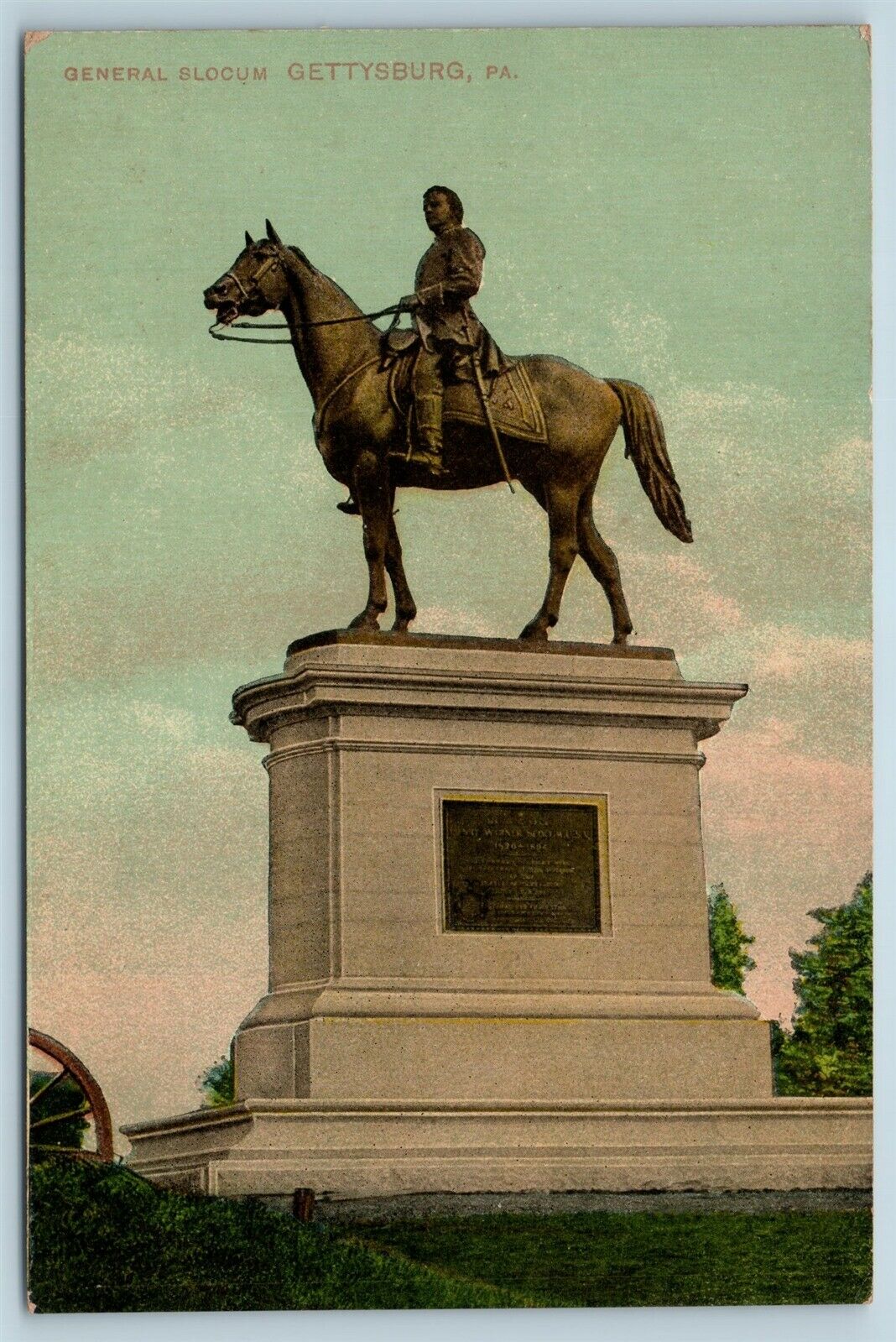

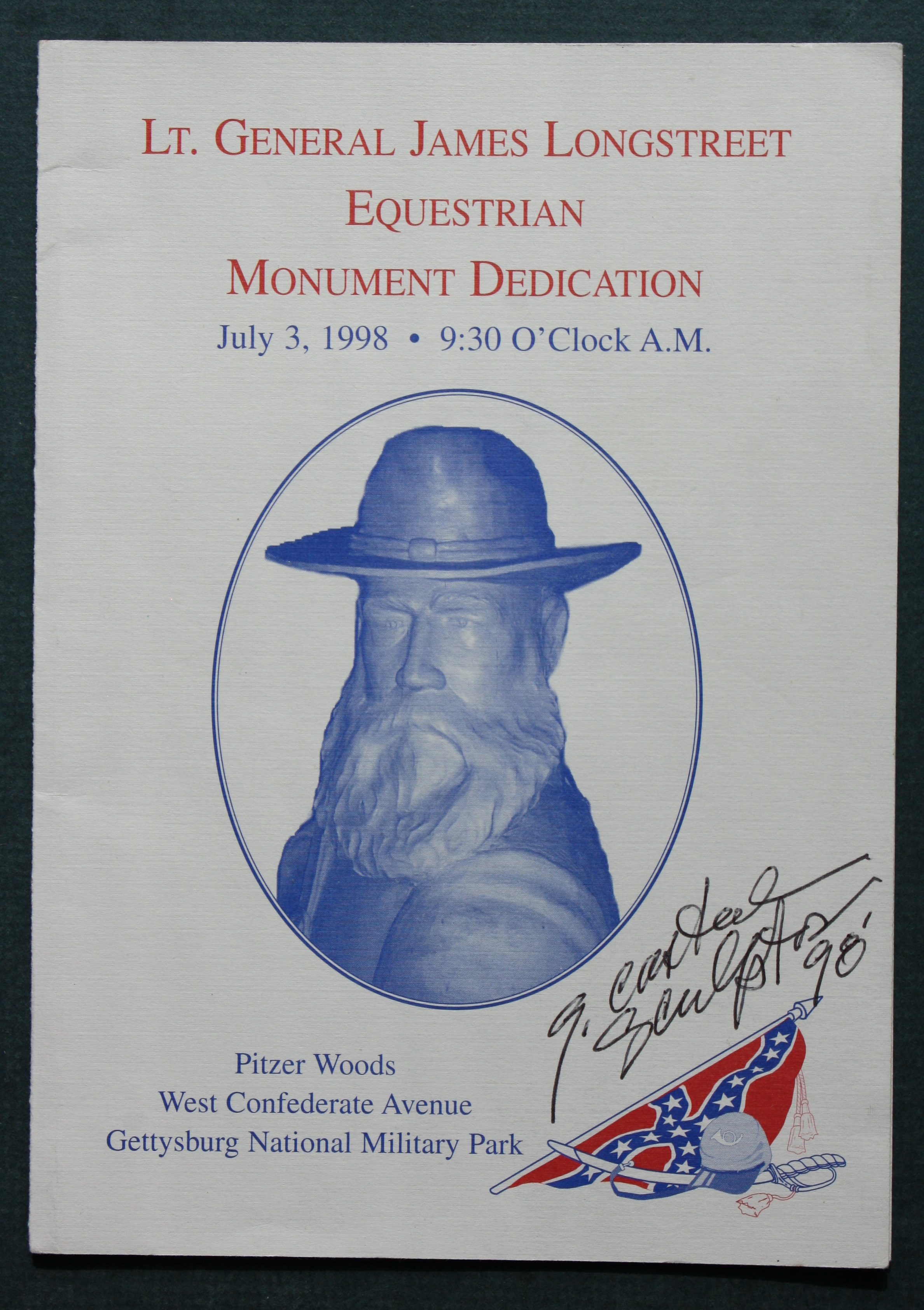

The statues on the field represent Union Generals Meade, Reynolds, Hancock, Howard, Slocum, and Sedgwick, and Confederates, Lee, atop the Virginia Memorial, and James Longstreet. According to the NPS, “Meade and Hancock were the first on June 5, 1896. They were followed by Reynolds, July 1, 1899, Slocum, September 19, 1902, Sedgwick, June 19, 1913, and Howard, November 12, 1932. The Virginia Memorial was dedicated on June 8, 1917. Longstreet did not come along until 1998 and by this time the myth was firmly established.”

The statues on the field represent Union Generals Meade, Reynolds, Hancock, Howard, Slocum, and Sedgwick, and Confederates, Lee, atop the Virginia Memorial, and James Longstreet. According to the NPS, “Meade and Hancock were the first on June 5, 1896. They were followed by Reynolds, July 1, 1899, Slocum, September 19, 1902, Sedgwick, June 19, 1913, and Howard, November 12, 1932. The Virginia Memorial was dedicated on June 8, 1917. Longstreet did not come along until 1998 and by this time the myth was firmly established.” But Hancock’s horse at Gettysburg? No one knows. Likewise, General O.O. Howard’s horse remains nameless (he had at least two shot out from under him and himself was wounded twice in battle) but the sternly pious one-armed General’s nickname of “Uh Oh” survives. So named by soldiers because when the General showed up, one way or another, there was gonna be a fight (he was awarded the Medal of Honor for actions at Gettysburg). Look up at his statue the next time you’re walking the field and you’ll see the empty flap of his right arm (shot off at the Battle of Seven Pines a year earlier) pinned neatly to his coat.

But Hancock’s horse at Gettysburg? No one knows. Likewise, General O.O. Howard’s horse remains nameless (he had at least two shot out from under him and himself was wounded twice in battle) but the sternly pious one-armed General’s nickname of “Uh Oh” survives. So named by soldiers because when the General showed up, one way or another, there was gonna be a fight (he was awarded the Medal of Honor for actions at Gettysburg). Look up at his statue the next time you’re walking the field and you’ll see the empty flap of his right arm (shot off at the Battle of Seven Pines a year earlier) pinned neatly to his coat.

The Opera House hosted the first performance of the inflammatory anti-slavery play “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and its location straddling the North-South boundary caused quite a stir in the days leading up to the Civil War. During the “War of the Rebellion”, the building was used as “Hospital No. 9” and soldiers from both sides of the conflict could often be found lying side-by-side within its walls. In April of 1862, the steamer “H.J. Adams” delivered 200 wounded soldiers to the converted Opera House fresh from the killing fields of Shiloh. In these years before sterilization set the standard of hospital care, a wounded soldier sent to Hospital No. 9, as with any hospital North or South of the Mason-Dixon line, might as well have been handed a death sentence. Many a soldier in Hospital No. 9 would write letters telling friends and family that he was on the mend from a minor battle wound one day, only to die unexpectedly the next day from disease.

The Opera House hosted the first performance of the inflammatory anti-slavery play “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and its location straddling the North-South boundary caused quite a stir in the days leading up to the Civil War. During the “War of the Rebellion”, the building was used as “Hospital No. 9” and soldiers from both sides of the conflict could often be found lying side-by-side within its walls. In April of 1862, the steamer “H.J. Adams” delivered 200 wounded soldiers to the converted Opera House fresh from the killing fields of Shiloh. In these years before sterilization set the standard of hospital care, a wounded soldier sent to Hospital No. 9, as with any hospital North or South of the Mason-Dixon line, might as well have been handed a death sentence. Many a soldier in Hospital No. 9 would write letters telling friends and family that he was on the mend from a minor battle wound one day, only to die unexpectedly the next day from disease. Judy recalls how in 2001, her youngest son David was down in the building’s cellar “fishing” for old bottles in a cistern that he had removed the concrete covering from. “He was laying on his stomach down there alone when he suddenly felt someone tap him on the shoulder” she says, “he looked around expecting to see the source of the poking, but saw that he was still down there alone. Since that time, David does not like to be in the basement by himself.”

Judy recalls how in 2001, her youngest son David was down in the building’s cellar “fishing” for old bottles in a cistern that he had removed the concrete covering from. “He was laying on his stomach down there alone when he suddenly felt someone tap him on the shoulder” she says, “he looked around expecting to see the source of the poking, but saw that he was still down there alone. Since that time, David does not like to be in the basement by himself.” Spirits of a Civil War soldier and a woman in an old fashioned Antebellum Era dress have been seen lounging around the cafe area by a few folks. “Every once in awhile, we’ll get a psychic coming through here telling us that they see the spirits of several Civil War soldiers around the entire building and sense sadness in the basement area.” says Gwinn.

Spirits of a Civil War soldier and a woman in an old fashioned Antebellum Era dress have been seen lounging around the cafe area by a few folks. “Every once in awhile, we’ll get a psychic coming through here telling us that they see the spirits of several Civil War soldiers around the entire building and sense sadness in the basement area.” says Gwinn.