Original Publish Date March 14, 2024

Okay, okay, not likely…but possible. No one really knows EXACTLY where the Beef Manhattan was born, but most culinary historians agree that the dish (a diagonally cut roast beef sandwich split butterfly fashion with a generous scoop of mashed potatoes resting between the two halves and the whole shebang swimming in a pool of brown beef gravy) came from the eastside of Indianapolis.

Legend claims the Beef Manhattan was born at the Naval Air Warfare Center, a former US Navy facility located at Arlington Avenue and East 21st Street in Warren Township, a stone’s throw from Irvington. The knife and fork-plated comfort food was (allegedly) the brainchild of Manhattan-trained cooks working at the factory during World War II. Faced with an overage of Hoosier staples (meat, potatoes, & bread) these crafty Hell’s Kitchen food slingers came up with a plan.

A poor man’s version of the dish had been making the rounds of Manhattan (the most densely populated and smallest of the five boroughs of New York City) for generations. The difference was, that the first version contained mysterious New York City street meat, rolls, not bread, potatoes, and no gravy. We do not know the name of the chef (or chefs) who created it or, for that matter, the date the dish first showed up in the cafeteria of the Naval Ordnance Plant. But, the best guess is that the Beef Manhattan made its debut in the winter of 1942.

The plant opened that year, covering 1,000,000 square feet and employing 3,000 workers in avionics research and development. Construction began in 1941 and the plant became fully operational in 1943. The “NOP-I”, as it was known locally, was one of five inland sites selected in July 1940 by the US Department of the Navy Bureau of Ordnance for the manufacture of naval ordnance. The other plants were in Canton, Ohio; Center Line, Michigan; Louisville, Kentucky; and Macon, Georgia. The government-owned, contractor-operated (GOCO) plant was built for $13.5 million ($255 million in 2024 dollars) and the plant manufactured Norden bombsights until September 1945.

The plant opened that year, covering 1,000,000 square feet and employing 3,000 workers in avionics research and development. Construction began in 1941 and the plant became fully operational in 1943. The “NOP-I”, as it was known locally, was one of five inland sites selected in July 1940 by the US Department of the Navy Bureau of Ordnance for the manufacture of naval ordnance. The other plants were in Canton, Ohio; Center Line, Michigan; Louisville, Kentucky; and Macon, Georgia. The government-owned, contractor-operated (GOCO) plant was built for $13.5 million ($255 million in 2024 dollars) and the plant manufactured Norden bombsights until September 1945.

After World War II, the plant was renamed the Naval Avionics Center, where employees designed and built prototype avionics, including “electronic countermeasures, missile guidance technologies, and guided bombs.” In 1992, the facility changed its name to the Naval Air Warfare Center Aircraft Division. The site was closed in 1996 on the recommendation of the 1995 Base Realignment and Closure Commission at which time it transferred ownership to Hughes Electronics Corporation. In 1997, it was the “largest full-scale privatization of a military facility in U.S. history” at the time. Eventually, the company was acquired and renamed the Raytheon Analysis & Test Laboratory. As of 2022, the facility is privately owned by Vertex Aerospace and employs about 600.

While those are the facts about the origin of place for the Beef Manhattan, determining where it first hit the streets of Indianapolis is a little bit more speculative. The riddle begins with the name itself. It is a misnomer. The dish is one of two Manhattan-named staples with no ties to New York City other than a space on the menu. The other, Manhattan clam chowder, originated in Rhode Island. Sure, New York City can claim many different foods created within its five boroughs: Eggs Benedict & the Waldorf salad (Midtown), Chicken & Waffles (Harlem), The Reuben (Manhattan), and the Cronut (So-Ho), but the Beef Manhattan is pure Hoosier.

There are different variations. One calls for shredded, pot-roast style beef on two slices of white bread, mashed potatoes on the side, with a layer of brown gravy poured over all. While another insists that the mashed potatoes are placed on top of the sliced, but unseparated, sandwich which is then drowned in brown gravy. Some versions call for diagonal slices, others conventional center-sliced bread. Another variation is Turkey Manhattan, which substitutes turkey for roast beef, but that is an obvious imposter. And, although the dish is named after Manhattan, if you were to order it in a Gotham City restaurant, you’re likely to be served a cocktail (whiskey, sweet vermouth, bitters, and a maraschino cherry garnish). Beef Manhattan is unknown there, instead such dishes are usually called “open-face sandwiches” in the Big Apple.

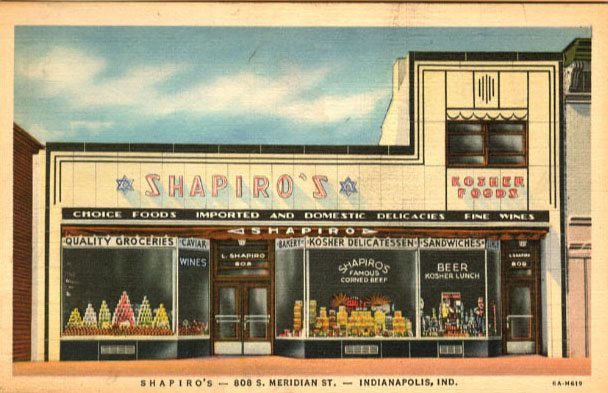

Should you Google it, you are likely to see that the dish was first served under the name “Beef Manhattan” in a now-defunct Indianapolis deli in the late 1940s, and shortly after its introduction, it became a Hoosier staple. But, nobody seems to know exactly which Indianapolis Deli was the first to put it on the menu. However, there are a few likely suspects. The natural choice would seem to be Shapiro’s. Their website states that restaurant namesakes, Louis and Rebecca Shapiro, arrived in the Hoosier state around 1900 after fleeing Russia due to anti-Semite persecution which included vandalism to their family grocery store in Odessa, Ukraine. They sold sugar and flour from a pushcart on the streets of Indianapolis for two years while saving up money to open their deli at Shapiro’s 808 South Meridian in 1905.

So, Shapiro ‘s certainly fits the bill timewise, appearing on the scene a generation before the birth of the Beef Manhattan. Shapiro’s is the sentimental favorite for sure. And it has an Irvington tie-in too. In 1925, during the reign of terror by the Ku Klux Klan in Indiana, Shapiro’s thumbed their nose at Klansman/Governor (and Irvington resident) Ed Jackson by redecorating their storefront in an art-deco style dominated by a huge Star of David for all to see. But officially, “Shapiro’s Kosher Deli” didn’t open until 1945, three years after the dish was invented.

Likewise, the Hook’s Drug Company opened a new drugstore and soda fountain at the corner of 22nd and Meridian Streets on Feb. 17, 1940 to serve hungry Hoosiers. Hook’s restaurant featured a new stainless steel soda fountain perfectly designed to serve Beef Manhattans. A contemporary news article described Hook’s as having “year-round air conditioning” and as “the last word in efficiency and beauty. The floor behind the fountain is depressed to a level so that the customer is sitting in the same comfortable position as at his own dining table. The fountain is provided with a system of sterilization which makes it sanitary for refreshments and luncheons. The cooking equipment is electrical.” Hook’s advertised heavily in the 1940s but never mentioned the Beef Manhattan in those ads. The dish did not appear in Hook’s ads until the 1950s.

The best bet (at least of this reporter) is that the Beef Manhattan most likely appeared first as a menu selection somewhere on Illinois Street. There were at least three delis operating on Illinois Street in 1942, including Brownie’s Kosher Deli at 3826 N. Illinois, Fox Delicatessen at 19 S. Illinois, and Henry Dobrowitz & Sons Kosher Meats and Delicatessen at 1002 S. Illinois. Someday, somewhere, a better Circle-city researcher than me will pinpoint the exact location but until then, I’m content to let it remain a mystery.

Choosing instead to revisit Shapiro’s version of the “Hot Beef Manhattan” in my daydreams. It consists of 2 slices of white bread, not cheap squishy white bread, but good firm white bread with some heft to it, cut diagonally and spread out on the plate like a poker hand, a layer of handmade mashed potatoes binds them together, and forms the foundation for a generous portion of thin-sliced tender beef, brisket I’m guessing. The meat mound is topped with more mashed potatoes and covered with enough gravy to float a kayak. Not that better than bouillon gravy stuff that somehow smacks of chemicals to me, but rather, real gravy made from the constant stirring of the collected juices of meats roasting. To those haughty Food Network snobs, the Beef Manhattan looks like a failure pile on a sadness plate, but Hoosiers know it is delicious.

Typically, Indianapolis sees 29 days a year where the thermometer doesn’t rise above 32 °F, and for five months a year, we’re shivering below the fifties. So, knowing that, is it that hard to understand why the Beef Manhattan remains so popular in Indiana? I mean, no one eats a tenderloin to get warm. And while the Beef Manhattan most likely wasn’t born in Irvington, it did originate on the east side of Indianapolis and Irvingtonians can fairly claim to be among the first wave of devotees.