Original publish date: April 8, 2021

Despite John Dillinger’s meteoric rise to infamy and spectacular headline grabbing death, his Indianapolis boyhood was unexceptional. He attended public schools for eight years in the Circle City and was a typical student. His teachers recalled that he liked working with his hands, was good with all things mechanical and liked reading better than math. He liked hunting, fishing, playing marbles, the Chicago Cubs and playing baseball. He was energetic and got along well with others (although he often bullied younger children), was cocky and quick witted. Dillinger quit school at age 16, not due to any trouble, but because he was bored and wanted to make money on his own.

During World War I, Dillinger tried to get a job at Link Belt in the city but was rejected because he was too young. Instead, he took a job as an apprentice machinist at James P. Burcham’s Reliance Specialty Company on the southwest side of Indianapolis and worked nights and weekends as an errand boy for the Indianapolis Board of Trade. All the while, Dillinger played second base on the company baseball team. One slot on Dillinger’s resume included a four day stint with the Indianapolis Power & Light Company drawing the hefty sum of 30 cents an hour. Just long enough for the “ringer” to help the IPL team win a league title.

In his spare time, Dillinger hung out at the local pool hall where he drank and smoked with the older men and cavorted with the local prostitutes. One of the regulars later recalled, “John would come in, hang up his hat and play pool at a quarter a game. He wasn’t very good, and he frequently lost. When he would lose two dollars, he’d put back the cue, get his cap, and walk out without a word. Never gave anyone any trouble and never said much.”

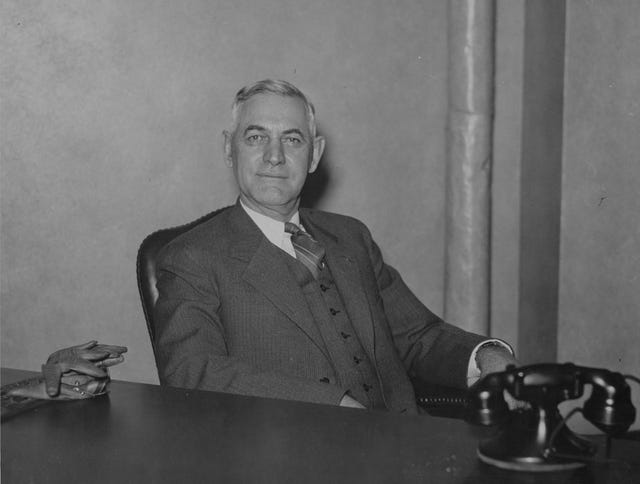

John Dillinger, Sr.

John Dillinger, Sr.

In 1920, his father, John Dillinger Sr., believing that the city was corrupting his son, sold his eastside Indianapolis Maywood grocery store property and moved his family to Mooresville. For the next 3 years, young Dillinger split his time between Moorseville, Martinsville and Indianapolis, traveling by interurban or motorcycle nearly every day. The athletic Dillinger quickly caught on with the semipro Mooresville Athletic Club’s “Athletics” baseball team. His reputation on the local sandlots and his quick speed earned him the nickname “The Jackrabbit”.

The 5-foot-7, 150 pound middle infielder batted leadoff and led the Athletics in hitting, for which the team’s sponsor, the Old Hickory Furniture Company, gave him a $25 reward on their way to the 1924 league championship. His game was so tight that other local teams began to pay him to play ball for them and throughout that summer the cash poured in.

Dillinger’s younger sister Frances, who passed away in 2015, insisted that her brother was good enough to draw Major League scouts to tiny Martinsville just to watch him play. Flush with confidence and blinded by the glare of an obviously bright future, Dillinger married Beryl Ethel Hovious in Mooresville on April 12, 1924. The couple moved into his father’s farm house but within a few weeks of the wedding, the groom was arrested for stealing 41 Buff Orpington chickens from Omer A. Zook’s farm on the Millersville Road.

Though his father was able to work out a deal to keep the case out of court, it further strained his relationship between them. Dillinger and Beryl moved out of their cramped bedroom and into Beryl’s parents’ home in Martinsville. There Dillinger got a job in an upholstery shop. All the while, Dillinger continued to play baseball. In between calling balls and strikes during AC Athletics games, umpire Ed Singleton (a web-fingered local drunk and pool shark 11-years his senior) was in the young shortstop’s ear. Singleton said he knew an old man, Frank Morgan, who carried loads of cash in his pockets around the streets of Mooresville.

Beryl Hovius and John Dillinger

On September 24, 1924, the young and impressionable Dillinger accompanied Singleton on what turned out to be a botched stick-up. After ambushing Morgan with a heavy iron bolt wrapped in a cotton handkerchief and knocking him unconscious, Dillinger fled the scene, thinking he had killed his victim. Turns out the bolt was not heavy enough to render an unconscious blow so Dillinger pistol whipped the old man in the face. The gun went off, firing harmlessly into the ground, unbeknownst to the young hoodlum. The robbery netted just $50 ($750 in today’s money).

Upon hearing the gunshot, Singleton panicked and drove away with the getaway car, stranding Dillinger, who ducked into a pool hall a few blocks away. Dillinger was arrested the next day at his father’s farm and held in the county jail in Martinsville. His father visited him there and told “Junior”, “Johnnie if you did this thing, the only way is to own up to it. They’ll go easy on you and you’ll get a new start.” Dillinger, who did not have a lawyer, pled guilty and received a 10-year prison sentence. His accomplice Ed Singleton hired a lawyer and received just 5 years. John Dillinger had launched himself into the big leagues of professional crime. But again, baseball would play a pivotal role in the young outlaw’s life.

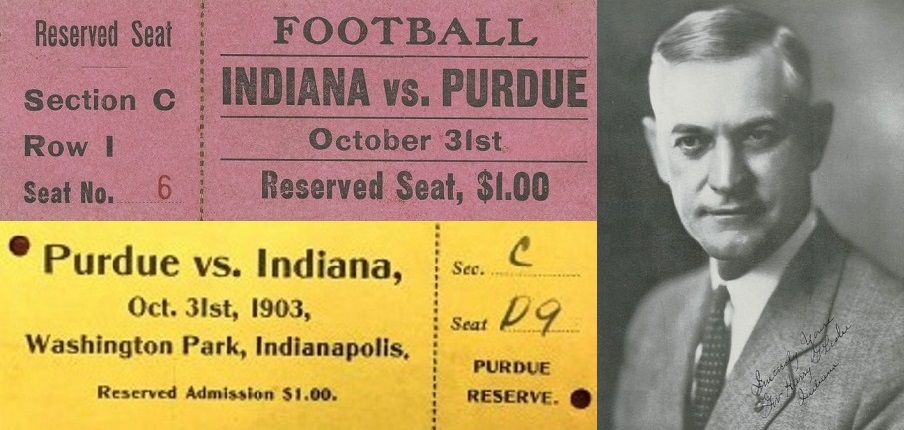

While incarcerated at the Indiana Reformatory in Pendleton, Prison officials recognized his superior ball playing skills and quickly recruited him for the prison ball club. On July 22, 1959, the 25th anniversary of Dillinger’s death, the Indianapolis News ran an article on Dillinger the ballplayer by “Outdoor Columnist” Tubby Toms. “His play was marvelous, both in the field and at bat… He might have been a Major League shortstop the caliber of a Pee Wee Reese or a Phil Rizzuto.” Tubby further mentioned an interaction between Governor Harry G. Leslie and Dillinger. Leslie, who has been detailed in a couple of my past columns, was a legendary athlete at Purdue University. Leslie always made it a point to stop and linger on visits to watch the prison ballplayers in action.

Tubby, who was the News Statehouse reporter at the time, recalls a 1932 visit to the prison with Governor Leslie when both men watched the reformatory’s baseball team take on a local semipro club. The two men couldn’t take their eyes off the shortstop whom fellow inmates were calling “jackrabbit”. Governor Leslie strongly believed in the rehabilitative power of organized competition and took a keen interest in inmates who applied themselves and excelled. So it wasn’t unusual that Dillinger captured his attention.

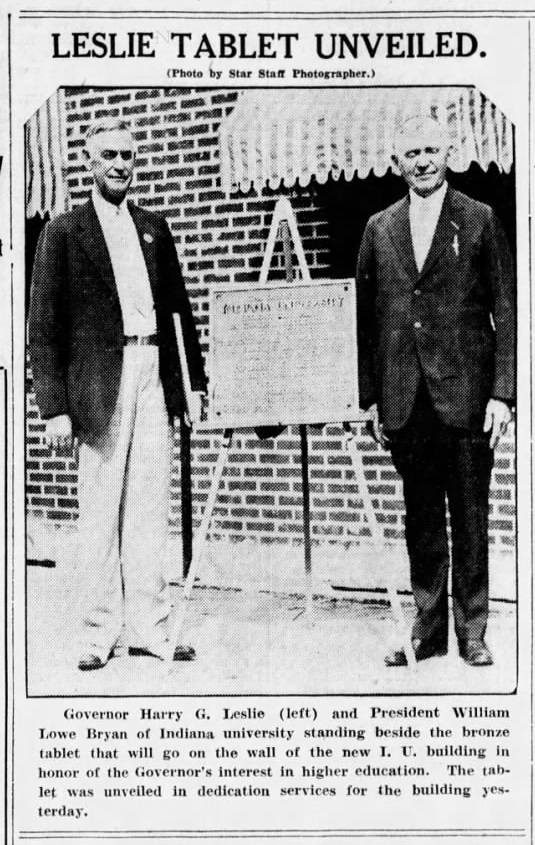

Governor Harry Leslie

Later that day, as fate would have it, Governor Leslie presided over Dillinger’s parole hearing. After Dillinger was once again denied parole, the dejected outlaw asked a question of the board. “I wonder if it would be possible to transfer me to the State Prison up at Michigan City? They’ve got a REAL ball team up there.” The Governor then said, “Gentlemen, I saw this lad play baseball this afternoon, and let me tell you, he’s got major league stuff in him. What reason can there be for denying him this request? It may play an important part in his reformation.” His request was granted and to this day, his official records state that he was sent to the big house “so he can play baseball.” It was at Michigan City where John Dillinger, under the tutelage of more seasoned cons, learned how to be a bank robber.

On May 22, 1933, Governor Paul McNutt released Dillinger from State Prison. Within a month, he held up the manager of a thread factory in Monticello, Illinois. A month after that, he held up a drugstore in Irvington. From there, he graduated to robbing banks. Dillinger followed his beloved Cubbies for the rest of his short life. Legend states that he even attended a few games at Wrigley Field while perched atop J. Edgar Hoover’s most wanted list. In fact, while playing toss in the outfield before a game in August of 1933, the bank robber was pointed out to outfielder Babe Herman as he sat with a group in the left field box seats. Cubs Hall of Fame catcher Gabby Hartnett often recalled how Chicago police routinely knew that Dillinger was in the crowd of Cubby faithful at Wrigley Field but never turned him into the G-men. Cubs all-star Woody English was once stopped on his way to the ballpark because he drove the same model of car as the outlaw did.

In a letter to his niece Mary, with whom he used to play catch, Dillinger said he was going to try and head east to see the Giants play the Senators in the 1933 World Series. Unfortunately, he was arrested on Sept. 22, 11 days before the start of the Fall Classic. He did, however, make money betting on the Giants, who won the series in five games. The 1933-1934 hot stove season was a busy one for Dillinger. He busted out of two jails and on June 22, 1934, J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI officially dubbed him Public Enemy No. 1. Dillinger responded by hiding out in plain sight in the city of big shoulders. He went to movies, partied at night clubs, toured the Chicago World’s Fair (more than once), and took in several Cubs games.

After a near fatal, botched plastic surgery in May of 1934, Dillinger dyed his hair, grew a mustache, and sported dark sunglasses to attend games at Wrigley to test out his new look out. One of Dillinger’s known hideouts in Chicago was an apartment at 901 W. Addison St., just two blocks east of Wrigley Field. On June 8th, Dillinger watched as his Cubs witness from the season before, Babe Herman, hit a 2-run homer in a loss to Cincinnati 4-3. In a story that made newspapers nation-wide, Dillinger watched from the upper deck as again Babe Herman drove in a pair of runs during a June 26th game as the Cubs defeated the Brooklyn Dodgers 5-2.

Mailman Robert Volk, who was in the garage in Crown Point on March 3, 1934 when Dillinger broke out of jail, instantly recognized the arch-criminal and the robber recognized him too. The outlaw got up and sat down next to the terrified man. After sitting in chilled silence for a while, Volk shakily said “this is getting to be a habit”, to which America’s most wanted bank robber replied “it certainly is.” Dillinger smiled and shook the mailman’s hand, introduced himself as “Jimmy Lawrence”, and left during the 7th inning stretch.

Despite this close call, Dillinger returned to Wrigley again on July 8th to watch the Pirates get pounded by his Cubbies 12-3 (for the sake of continuity, Babe Herman went 1 for 5 in this one). After the blowout, the Cubs left on an extended road trip. They were still on the road against the Phillies on July 22 when Dillinger decided to catch a movie at the Biograph Theatre. The White Sox were in town that afternoon playing a double-header against the Yankees. The Bronx Bombers ‘moidered” the north-siders in both contests. Had Dillinger been a White Sox fan he might have avoided his date with destiny and lived to die another day. He might have been in the bleachers to catch Babe Ruth’s 16th homer that day. Instead he caught a hail of bullets in a damp Chicago alleyway. According to the Cook County coroner, the jackrabbit was only three pounds above his old playing weight.

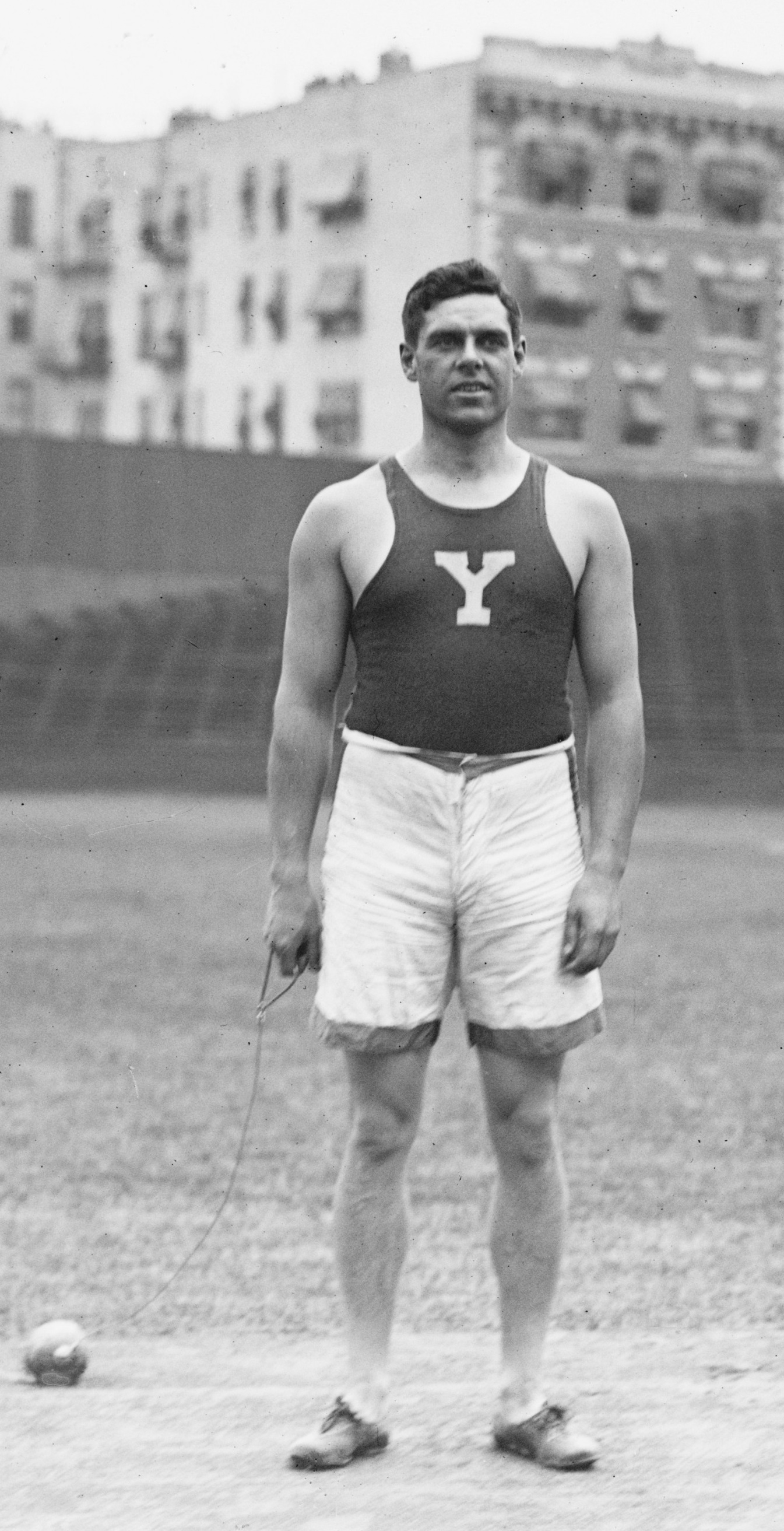

The Indianapolis star reported, “After some three weeks of anxious waiting, (John) McGraw’s national pastimers turn over to the University coaching staff one of the greatest athletes the world has ever known, James Thorpe. He and his family will arrive in this city Thursday evening at 7 o’clock. Thorpe will take up his duties as assistant coach Friday afternoon…Students, alumni and, in fact, the entire college world looks forward to the coming of this great athlete, with great eagerness to know exactly how his coaching will compare with his known ability as a player. In fact, the thing foremost in the minds of these men is, can this All-American star teach the Indiana backfield men the tricks that made him so famous at Carlisle?”

The Indianapolis star reported, “After some three weeks of anxious waiting, (John) McGraw’s national pastimers turn over to the University coaching staff one of the greatest athletes the world has ever known, James Thorpe. He and his family will arrive in this city Thursday evening at 7 o’clock. Thorpe will take up his duties as assistant coach Friday afternoon…Students, alumni and, in fact, the entire college world looks forward to the coming of this great athlete, with great eagerness to know exactly how his coaching will compare with his known ability as a player. In fact, the thing foremost in the minds of these men is, can this All-American star teach the Indiana backfield men the tricks that made him so famous at Carlisle?” Thorpe’s presence fired up the crowd as IU jumped out to a 34-0 lead by halftime. IU fans thrilled to the sight of Thorpe pacing the sideline. IU hammered Miami 41-0 in front of a huge crowd at Jordan Field. By the next Tuesday, Thorpe was finally getting in some real work with the kickers. The Daily Student noted, “Before the scrimmage, assistant coach Thorpe had the kickers out in the center of the arena instructing them in getting off their punts in good form…The Indian’s long, twisting spirals were not duplicated by either Scott or Whitaker, although both Crimson backs showed much improvement over past performances.”

Thorpe’s presence fired up the crowd as IU jumped out to a 34-0 lead by halftime. IU fans thrilled to the sight of Thorpe pacing the sideline. IU hammered Miami 41-0 in front of a huge crowd at Jordan Field. By the next Tuesday, Thorpe was finally getting in some real work with the kickers. The Daily Student noted, “Before the scrimmage, assistant coach Thorpe had the kickers out in the center of the arena instructing them in getting off their punts in good form…The Indian’s long, twisting spirals were not duplicated by either Scott or Whitaker, although both Crimson backs showed much improvement over past performances.” After the game, Thorpe spent his time on Jordan Field practicing kicking by himself. One IDS reporter noted on October 19th, “No one was around – there was no grandstand play – just a step, a quick swing of the leg and a double-thud as the ball hit ground and cleated shoe at the same instant. The kicker was “Jim” Thorpe, late addition to the Crimson coaching staff. He stood on the line which divides the gridiron into two equal portions, a little toward the sideline to avoid the mud. There was a flash of red and brown as his leg swung to meet the rising pigskin and away sailed the ball, end over end, squarely between the white posts at the end of the field. The long kick was accomplished with so much ease and grace that it appeared the least difficult feat in the world, but the big Indian merely smiled. It’s not “being done” on many gridirons this season, however, so old Jordan Field ought to feel mighty proud.”

After the game, Thorpe spent his time on Jordan Field practicing kicking by himself. One IDS reporter noted on October 19th, “No one was around – there was no grandstand play – just a step, a quick swing of the leg and a double-thud as the ball hit ground and cleated shoe at the same instant. The kicker was “Jim” Thorpe, late addition to the Crimson coaching staff. He stood on the line which divides the gridiron into two equal portions, a little toward the sideline to avoid the mud. There was a flash of red and brown as his leg swung to meet the rising pigskin and away sailed the ball, end over end, squarely between the white posts at the end of the field. The long kick was accomplished with so much ease and grace that it appeared the least difficult feat in the world, but the big Indian merely smiled. It’s not “being done” on many gridirons this season, however, so old Jordan Field ought to feel mighty proud.” On the day of the game, Nov. 20, Jordan Field was covered with sawdust to try to dry the water left by the snow, sleet and the rain of the past week. A crowd of more than 7,000 packed Jordan Field to see IU battle the Boilermakers in the old oaken bucket game. Purdue won 7-0. Thorpe put on another punting exhibition for the crowd at halftime. This one wasn’t as spirited as the Chicago exhibition the week before. Understandable because, Thorpe had a game to play the next day in Canton. Thorpe arrived in time for the second game in three weeks between Canton and Massillon, and he took over as head coach of the Bulldogs. In the game, Thorpe drop-kicked a field goal from 45 yards out in the first quarter and added a place kick of 38 yards in the third quarter to push Canton to a 6-0 victory.

On the day of the game, Nov. 20, Jordan Field was covered with sawdust to try to dry the water left by the snow, sleet and the rain of the past week. A crowd of more than 7,000 packed Jordan Field to see IU battle the Boilermakers in the old oaken bucket game. Purdue won 7-0. Thorpe put on another punting exhibition for the crowd at halftime. This one wasn’t as spirited as the Chicago exhibition the week before. Understandable because, Thorpe had a game to play the next day in Canton. Thorpe arrived in time for the second game in three weeks between Canton and Massillon, and he took over as head coach of the Bulldogs. In the game, Thorpe drop-kicked a field goal from 45 yards out in the first quarter and added a place kick of 38 yards in the third quarter to push Canton to a 6-0 victory. Jim Thorpe left Bloomington to continue his professional athletic career in baseball and football. He helped Canton win three Ohio League championships, reportedly sealing the 1919 title with a wind-assisted 95-yard punt late in the game. Thorpe eventually played for six NFL teams, although he never won a title, and he retired from football in 1928. He played Major League Baseball with the Giants, the Cincinnati Reds and the Boston Braves, compiling a career batting average of .252 in 289 games before retiring in 1919. He would be named the greatest athlete of the first half of the 20th century by the Associated Press and was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1951 and the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1963.

Jim Thorpe left Bloomington to continue his professional athletic career in baseball and football. He helped Canton win three Ohio League championships, reportedly sealing the 1919 title with a wind-assisted 95-yard punt late in the game. Thorpe eventually played for six NFL teams, although he never won a title, and he retired from football in 1928. He played Major League Baseball with the Giants, the Cincinnati Reds and the Boston Braves, compiling a career batting average of .252 in 289 games before retiring in 1919. He would be named the greatest athlete of the first half of the 20th century by the Associated Press and was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1951 and the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1963. One of Thorpe’s odd jobs was serving as a traveling softball umpire. When I was young collector, I purchased an old World War II softball in a box. It belonged to man who had received the ball as his own personal trophy for being named MVP of some long forgotten tournament. He mentioned that the ball had been signed by the tourney umpire. A man named Jim Thorpe. I opened the box and looked at the fountain pen signature, crisp as the day it had been signed. “You probably don’t know who that is.” the old man said. To which I answered, “Oh, I know who it is,” I answered. I’m an IU grad as are both of my children. And for a time, Jim Thorpe was one of us. That ball was sold off many years ago when the responsibility and expense of raising children trumped the need for sentimental objects. But the memory remains,

One of Thorpe’s odd jobs was serving as a traveling softball umpire. When I was young collector, I purchased an old World War II softball in a box. It belonged to man who had received the ball as his own personal trophy for being named MVP of some long forgotten tournament. He mentioned that the ball had been signed by the tourney umpire. A man named Jim Thorpe. I opened the box and looked at the fountain pen signature, crisp as the day it had been signed. “You probably don’t know who that is.” the old man said. To which I answered, “Oh, I know who it is,” I answered. I’m an IU grad as are both of my children. And for a time, Jim Thorpe was one of us. That ball was sold off many years ago when the responsibility and expense of raising children trumped the need for sentimental objects. But the memory remains,

Thorpe played professional football in 1913 as a member of the Indiana-based Pine Village Pros, a team that had a several-season winning streak against local teams during the 1910s. Also that year, Thorpe signed pro contracts to play baseball with the New York Giants and football for the Chicago Cardinals and Canton (Ohio) Bulldogs. The Bulldogs paid Thorpe $ 250 per game ($5,919 today) a huge sum for the time. Overnight, the Bulldogs went from drawing 1,200 fans per game to 8,000. Thorpe was front page news, leading the Bulldogs to league championships in 1916, 1917 and 1919. In 1920, the Bulldogs and 13 other teams formed the APFA (American Professional Football Association) the forerunner of today’s NFL and Thorpe was elected the league’s first president. You might say that Jim Thorpe was a big deal.

Thorpe played professional football in 1913 as a member of the Indiana-based Pine Village Pros, a team that had a several-season winning streak against local teams during the 1910s. Also that year, Thorpe signed pro contracts to play baseball with the New York Giants and football for the Chicago Cardinals and Canton (Ohio) Bulldogs. The Bulldogs paid Thorpe $ 250 per game ($5,919 today) a huge sum for the time. Overnight, the Bulldogs went from drawing 1,200 fans per game to 8,000. Thorpe was front page news, leading the Bulldogs to league championships in 1916, 1917 and 1919. In 1920, the Bulldogs and 13 other teams formed the APFA (American Professional Football Association) the forerunner of today’s NFL and Thorpe was elected the league’s first president. You might say that Jim Thorpe was a big deal.

Even though I was very young, I can remember that in May of 1968, Hollywood came to town to film a major movie at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Although I didn’t know it at the time, the film was called “Winning,” and starred Paul Newman and his real-life wife, Joanne Woodward. The plot focused on an ambitious race driver determined to win the Indianapolis 500 in an effort to resurrect his flagging career. The film also starred Richard Thomas, soon to become more famous as “John Boy” on “The Waltons” TV series and Robert Wagner (of “Hart to Hart” TV fame). Several real-life racing figures-including the Speedway’s owner, Tony Hulman, and race driver Bobby Unser-portray themselves in the movie.

Even though I was very young, I can remember that in May of 1968, Hollywood came to town to film a major movie at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Although I didn’t know it at the time, the film was called “Winning,” and starred Paul Newman and his real-life wife, Joanne Woodward. The plot focused on an ambitious race driver determined to win the Indianapolis 500 in an effort to resurrect his flagging career. The film also starred Richard Thomas, soon to become more famous as “John Boy” on “The Waltons” TV series and Robert Wagner (of “Hart to Hart” TV fame). Several real-life racing figures-including the Speedway’s owner, Tony Hulman, and race driver Bobby Unser-portray themselves in the movie.

A total of 17 people died immediately, including 13 players, a coach, a trainer, a student manager and a booster. One member of the team miraculously landed on his feet and was unharmed after being thrown out a window. All the casualties were limited to the team’s railcar. Twenty-nine more players were hospitalized, several of whom suffered crippling injuries that would last the rest of their lives. Further tragedy was averted when several people, led by the “John Purdue Special” brakeman, ran up the track to slow down the second special train that was following 10 minutes behind the first. This heroic action undoubtedly saved many lives by preventing another train wreck. One of the survivors of the wreck was Purdue University President Winthrop E. Stone who remained on the scene to comfort the injured and dying.

A total of 17 people died immediately, including 13 players, a coach, a trainer, a student manager and a booster. One member of the team miraculously landed on his feet and was unharmed after being thrown out a window. All the casualties were limited to the team’s railcar. Twenty-nine more players were hospitalized, several of whom suffered crippling injuries that would last the rest of their lives. Further tragedy was averted when several people, led by the “John Purdue Special” brakeman, ran up the track to slow down the second special train that was following 10 minutes behind the first. This heroic action undoubtedly saved many lives by preventing another train wreck. One of the survivors of the wreck was Purdue University President Winthrop E. Stone who remained on the scene to comfort the injured and dying. Walter Bailey, a reserve player from New Richmond, was grievously injured but refused aid so that others could be helped before him. Bailey would die a month later at the hospital from complications from his injuries and massive blood loss. Purdue team Captain Harry “Skeets” Leslie was found with ghastly wounds and covered up for dead. His body was transported to the morgue with the others. Leslie would later be upgraded to “alive” when, while his body lay on a cold slab at the morgue, someone noticed his right arm move slightly and he was found to have a faint pulse. Skeets was clinging to life for several weeks and needed several operations before he was out of the woods. Leslie would later go on to become the state of Indiana’s 33rd governor, the only Purdue graduate to ever hold that office. As a reminder of that Halloween train disaster, Skeets would walk with a limp for the rest of his life.

Walter Bailey, a reserve player from New Richmond, was grievously injured but refused aid so that others could be helped before him. Bailey would die a month later at the hospital from complications from his injuries and massive blood loss. Purdue team Captain Harry “Skeets” Leslie was found with ghastly wounds and covered up for dead. His body was transported to the morgue with the others. Leslie would later be upgraded to “alive” when, while his body lay on a cold slab at the morgue, someone noticed his right arm move slightly and he was found to have a faint pulse. Skeets was clinging to life for several weeks and needed several operations before he was out of the woods. Leslie would later go on to become the state of Indiana’s 33rd governor, the only Purdue graduate to ever hold that office. As a reminder of that Halloween train disaster, Skeets would walk with a limp for the rest of his life.