Original Publish Date August 26, 2021.

Recently, I ran across an obscure booklet about a little-known episode in the post-assassination chronology of Abraham Lincoln. Surprisingly it was published and distributed by a man named Stewart Winning McClelland (1891-1977) a self-described “Sponsor” of Dale Carnegie courses from Indianapolis. More surprising is the fact that it was published exactly 70 years ago on August 28, 1951. The booklet is titled “A Monument to The Memory Of John Wilkes Booth.” Now THAT got your attention, didn’t it?

The booklet tells the story of a cranky old Rebel from Troy Alabama named Joseph Pinckney “Pink” Parker, born August 16, 1839, and died December 12, 1921. Parker, a former police officer and veteran of the Confederate Army, was often described in the local newspaper as “the bitterest Rebel in the South.” Almost immediately after graduating from Springhill Academy in Coffee County Alabama, the Civil War broke out and Pink enlisted in the Confederate Army. He left his family’s well-stocked plantation, a sister, and a bevy of slaves when he left for the front lines.

Parker served in Company A of the Second Georgia Battalion Infantry, Wright’s Brigade, Mohone’s Division of AP Hill’s Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia. During Parker’s four years of service, he rose to the rank of Corporal and fought at the battles of Gettysburg, the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor, Petersburg, and Appomattox: many of the fiercest battles of the Civil War.

Four years later, when the war ended, Pink returned to find the “farm overgrown with weeds, his stock and slaves disappeared and his sister imbittered by her treatment received at the hands of the northern soldiers.” The family estate was soon “eaten up” by taxes and the former Rebel soldier was forced to take a position as a “walker” on the railroad tracks carrying with him “maul and spikes to keep the tracks repaired.” Parker grew to hate everything “Yankee”, blaming President Abraham Lincoln for the social and economic distress throughout the South and for Reconstruction, which he considered the continued destruction of the South.

Parker married and bought a farm near Inverness, Florida, but found farm life there hard and unforgiving. He moved his wife and three children to a house he bought on Madison Street in Troy. For years he earned a hardscrabble living on his meager salary as a grocery store clerk, policeman, and cotton compress worker. Eventually, he became a schoolteacher in Troy, where he built a comfortable home a short distance from the famed Natchez trace “which Andrew Jackson used in his battles against the Indians in Florida.”

The booklet describes Pink as a well-respected member of his community and a devout member of the Baptist Church with just one single vice: a deep-seated hatred for Abraham Lincoln. As Lincoln’s legend began to move towards secular sainthood, in both the North and the South, Pink Parker’s wrath grew year by year into a compulsion. Whenever Lincoln’s name was mentioned, Pink would burst forth with impassioned flights of profanity that astonished and shocked his friends and family. So bad were these outbursts that his pastor at the Baptist Church removed him from the church roles for his profanity. In a situation that Pink described, “It wasn’t quite fair. I know all the deacons in that church and any one of them can cuss better than I can.”

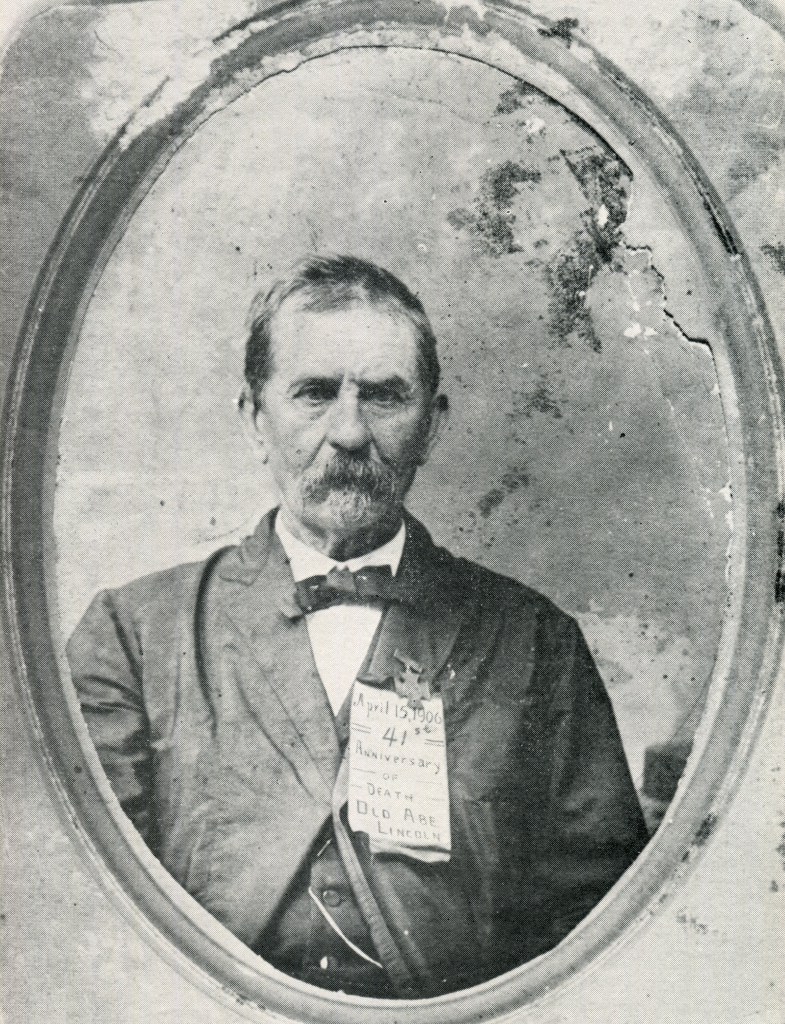

His expulsion from the church proved to be the capstone of Parker’s Lincoln hatred. Parker’s wife died in 1893 and his children moved away. From that point on, every April 15th, Pink would fashion for himself a paper badge and ribbon celebrating the “Anniversary of the Death of old Abe Lincoln.” Occasionally, Pink would memorialize these otherwise sad anniversaries by walking into the local photography studio to have his picture made wearing the offensive badge. As years passed, the idea came into his head that he would erect a monument to the memory of John Wilkes Booth. As unthinkable and repulsive as the idea sounds to our modern ears, Pink indeed put his plan into action.

The monument, standing approximately 4 feet high, resembled a typical graveyard headstone found in any Alabama burying ground around the state. Pink was always quick to note that he never took the oath of allegiance after the Civil War and he personally never surrendered. The stone bore the inscription: “Erected by Pink Parker in honor of John Wilks Booth, for killing old Abe Lincoln.” It is interesting to note that the old Rebel misspelled the cowardly assassin’s name on his memorial, fitting for such an unpopular, shortsighted memorial.

He first offered his ghastly memorial to the city of Troy to be placed in front of the Pike County Courthouse or in a public park. When the city quickly declined his invitation, he installed the monument in his front yard on Madison Street. It wasn’t long before local vandals turned their attention to the stone, defacing it. Soon Parker erected a board fence to protect it. Although newspapers from the 1920s stated that the stone had been erected in 1866, Pink placed the marker in 1906. Pink told his grandsons that he invited President Theodore Roosevelt to the stone’s dedication with a postcard stating that “while I can’t furnish a carriage for you, I could get you a dray hauled by a couple of mules.”

When those same grandsons asked their grandfather how he was going to get along with all those Yankees when he got to heaven, Pink would say, “Well, I don’t suppose I will find enough up there to bother me.” Pink Parker always believed that John Wilkes Booth was still alive, that Booth did not die from Boston Corbett’s shot through the neck in the Garrett tobacco barn. A belief principally subscribed to by only the most avowed skeptics, conspiracy theorists, and carnival sideshow aficionados of the era.

Parker became ill and, in 1918, his son, Eugene, moved his father to Sardis, Georgia. Parker deeded his home to his three children. They sold it in 1920. In 1921 emotions over Pink’s distasteful display reached a boiling point. The local president of the Alabama Women’s League of Republican Voters, Mrs. C.D. Brooks, instigated a campaign to have the monument removed permanently. Letters poured in from all over the country supporting her stand. Then sometime around Halloween, a group of local boys pulled down the marker as a prank. The Booth monument lay half-buried in the dirt as weeds slowly overtook it.

In 1921, the Troy Messenger received a large volume of indignant letters and the National Sons of Union Veterans wrote to President Waren G. Harding demanding the monument be removed and destroyed. The added attention and the age of the automobile soon brought souvenir hunters to the little town of Troy. These eager relic collectors began to chip away pieces of the stone. The Troy Messenger reported on July 13, 1921, that the monument had been removed by order of the town council. It was hidden away out of sight and mind in a shed and forgotten.

In the midst of the furor, the half-blind, sick, and forgotten Pink Parker passed away in December of 1921 at the age of 82. His body was brought back to Troy and buried next to his wife. His sons retrieved the stone from cold storage and had it re-carved. The inscription honoring Booth was removed from the monument and it was fashioned into his tombstone, his name and birth/death dates on one side and the details of his service in the Confederate Army listed on the other. Confederate veterans served as his pallbearers.

Historians have long realized how much the South lost by the killing of Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln was the one man who might have reunited a broken country. The one man who could have allayed sectional hostilities and rebuilt a nation. Pink Parker was on the wrong side of history. But Pink Parker did not care. Today, the former Booth monument can be seen on Parker’s grave in Oakwood Cemetery, located on North Knox Street in Troy. The gravestone stands on a downward slope in the farthest regions of the cemetery. There is no trace of the former writing, no indication that it ever honored assassin John Wilkes Booth. Perhaps fittingly, Pink Parker’s grave marker lists to the larboard side, forever tilted, just like the man it honors.

The president was scheduled to meet the thousands of people who, in spite of the oppressive heat, were waiting at the Temple of Music on the north side of the fairgrounds. In that line, no one stood out more than James “Big Ben” Parker, a six-foot six inch, 250 pound “Negro” waiter from Atlanta who has been laid off by the exposition’s Plaza Restaurant only days before. One could conclude that “Big Ben” was the angriest man in the room and the one the Secret Service should be watching. However, that sobriquet would belong to the man standing immediately in front of the gentle giant. A stoop-shouldered, nervous little man whose hand was wrapped in a handkerchief.

The president was scheduled to meet the thousands of people who, in spite of the oppressive heat, were waiting at the Temple of Music on the north side of the fairgrounds. In that line, no one stood out more than James “Big Ben” Parker, a six-foot six inch, 250 pound “Negro” waiter from Atlanta who has been laid off by the exposition’s Plaza Restaurant only days before. One could conclude that “Big Ben” was the angriest man in the room and the one the Secret Service should be watching. However, that sobriquet would belong to the man standing immediately in front of the gentle giant. A stoop-shouldered, nervous little man whose hand was wrapped in a handkerchief. The first bullet sheared a button off of McKinley’s vest, the second tore into the President’s abdomen. The handkerchief burst into flames and fell to the floor. McKinley lurched forward as Czolgosz took aim for a third shot. Within seconds after the second pistol shot, Big Ben Parker was grappling with the adrenaline charged assassin. Secret service special agent Samuel Ireland described the scene: “Parker struck the assassin in the neck with one hand and with the other reached for the revolver which had been discharged through the handkerchief and the shots had set fire to the linen. While on the floor Czolgosz again tried to discharge the revolver but before he got to the president the Negro knocked it from his hand.” A split second after Parker struck Czolgosz, so did Buffalo detective John Geary and one of the artillerymen, Francis O’Brien. Czolgosz disappeared beneath a pile of men, some of whom were punching or hitting him with rifle butts. The assassin cried out, “I done my duty.”

The first bullet sheared a button off of McKinley’s vest, the second tore into the President’s abdomen. The handkerchief burst into flames and fell to the floor. McKinley lurched forward as Czolgosz took aim for a third shot. Within seconds after the second pistol shot, Big Ben Parker was grappling with the adrenaline charged assassin. Secret service special agent Samuel Ireland described the scene: “Parker struck the assassin in the neck with one hand and with the other reached for the revolver which had been discharged through the handkerchief and the shots had set fire to the linen. While on the floor Czolgosz again tried to discharge the revolver but before he got to the president the Negro knocked it from his hand.” A split second after Parker struck Czolgosz, so did Buffalo detective John Geary and one of the artillerymen, Francis O’Brien. Czolgosz disappeared beneath a pile of men, some of whom were punching or hitting him with rifle butts. The assassin cried out, “I done my duty.” A Los Angeles Times story said that “with one quick shift of his clenched fist, he [Parker] knocked the pistol from the assassin’s hand. With another, he spun the man around like a top and with a third, he broke Czolgosz’s nose. A fourth split the assassin’s lip and knocked out several teeth.” In Parker’s own account, given to a newspaper reporter a few days later, he said, “I heard the shots. I did what every citizen of this country should have done. I am told that I broke his nose—I wish it had been his neck. I am sorry I did not see him four seconds before. I don’t say that I would have thrown myself before the bullets. But I do say that the life of the head of this country is worth more than that of an ordinary citizen and I should have caught the bullets in my body rather than the President should get them.” In a separate interview for the New York Journal, Parker remarked “just think, Father Abe freed me, and now I saved his successor from death, provided that bullet he got into the president don’t kill him.”

A Los Angeles Times story said that “with one quick shift of his clenched fist, he [Parker] knocked the pistol from the assassin’s hand. With another, he spun the man around like a top and with a third, he broke Czolgosz’s nose. A fourth split the assassin’s lip and knocked out several teeth.” In Parker’s own account, given to a newspaper reporter a few days later, he said, “I heard the shots. I did what every citizen of this country should have done. I am told that I broke his nose—I wish it had been his neck. I am sorry I did not see him four seconds before. I don’t say that I would have thrown myself before the bullets. But I do say that the life of the head of this country is worth more than that of an ordinary citizen and I should have caught the bullets in my body rather than the President should get them.” In a separate interview for the New York Journal, Parker remarked “just think, Father Abe freed me, and now I saved his successor from death, provided that bullet he got into the president don’t kill him.”

Historians agree that Czolgosz’s trial was a sham. Sadly, what should have been Big Ben Parker’s time to shine instead became his disappearing act. Prior to the trial, which began September 23, 1901, Parker was expected to be a major character in the assassination saga. Instead,the trial minimized Parker’s participation in the events of three weeks prior. Parker was never asked to testify and those few participants who did never identified Big Ben as the person who first subdued the assassin. Czolgosz’s sanity was never questioned and the case was closed twenty-four hours after it opened. Newspaper reports after the trial failed to mention Big Ben’s role and witnesses, including lawyers and Secret Service agents, began to enlarge their own roles in the tragedy by going as far as saying they “saw no Negro involved” whatsoever.

Historians agree that Czolgosz’s trial was a sham. Sadly, what should have been Big Ben Parker’s time to shine instead became his disappearing act. Prior to the trial, which began September 23, 1901, Parker was expected to be a major character in the assassination saga. Instead,the trial minimized Parker’s participation in the events of three weeks prior. Parker was never asked to testify and those few participants who did never identified Big Ben as the person who first subdued the assassin. Czolgosz’s sanity was never questioned and the case was closed twenty-four hours after it opened. Newspaper reports after the trial failed to mention Big Ben’s role and witnesses, including lawyers and Secret Service agents, began to enlarge their own roles in the tragedy by going as far as saying they “saw no Negro involved” whatsoever.

Just as Big Ben is the forgotten figure in the McKinley assassination saga, Leon Czolgosz is the least known of all presidential assassins. Prior to his execution Czolgosz met with two priests and said, “No. Damn them. Don’t send them here again. I don’t want them. And don’t you have any praying over me when I’m dead. I don’t want it. I don’t want any of their damned religion.” Czolgosz was electrocuted on October 29, 1901 at Auburn penitentiary. Initially, Czolgosz’s family wanted the body. The warden convinced them that it would be a bad idea, that relic hunters would disturb his grave, or worse, that unscrupulous carnival promoters would want to display the body in traveling sideshows.

Just as Big Ben is the forgotten figure in the McKinley assassination saga, Leon Czolgosz is the least known of all presidential assassins. Prior to his execution Czolgosz met with two priests and said, “No. Damn them. Don’t send them here again. I don’t want them. And don’t you have any praying over me when I’m dead. I don’t want it. I don’t want any of their damned religion.” Czolgosz was electrocuted on October 29, 1901 at Auburn penitentiary. Initially, Czolgosz’s family wanted the body. The warden convinced them that it would be a bad idea, that relic hunters would disturb his grave, or worse, that unscrupulous carnival promoters would want to display the body in traveling sideshows. His family agreed that the prison should take care of the funeral arrangements by giving the assassin a decent burial within the protection of the prison grounds. When Leon Czolgosz was buried in the Auburn prison cemetery, yards away from where he was executed, unbeknownst to the family, the decision was made to have his body destroyed. The local crematorium refused to undertake the job. So the assassin’s body was placed in a rough pine box and lowered into the ground which had been coated with quicklime. The lid was removed and two barrels of quicklime powder was caked on top of the body. Then sulfuric acid was poured on top of that followed by another two layers of quicklime.

His family agreed that the prison should take care of the funeral arrangements by giving the assassin a decent burial within the protection of the prison grounds. When Leon Czolgosz was buried in the Auburn prison cemetery, yards away from where he was executed, unbeknownst to the family, the decision was made to have his body destroyed. The local crematorium refused to undertake the job. So the assassin’s body was placed in a rough pine box and lowered into the ground which had been coated with quicklime. The lid was removed and two barrels of quicklime powder was caked on top of the body. Then sulfuric acid was poured on top of that followed by another two layers of quicklime. Their intention was to make the anarchist’s body dematerialize. What the prison officials did not know was that when quicklime (calcium oxide) and sulfuric acid are combined, a chemical reaction occurs which creates an exterior coating best compared to plaster of paris. Since the shell is insoluble in water, the coating acts as a protective layer thus preventing further attack on the corpse by the acid. It is entirely possible that the body of Czolgosz was preserved in perpetuity accidentally.

Their intention was to make the anarchist’s body dematerialize. What the prison officials did not know was that when quicklime (calcium oxide) and sulfuric acid are combined, a chemical reaction occurs which creates an exterior coating best compared to plaster of paris. Since the shell is insoluble in water, the coating acts as a protective layer thus preventing further attack on the corpse by the acid. It is entirely possible that the body of Czolgosz was preserved in perpetuity accidentally.

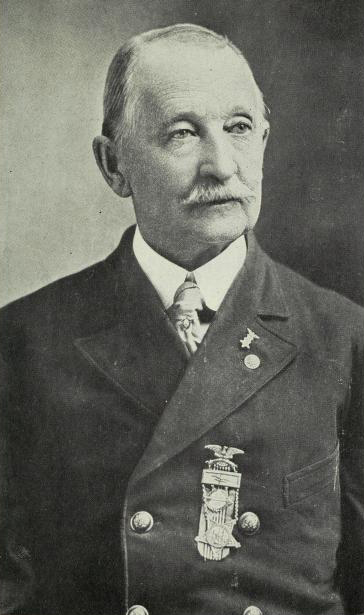

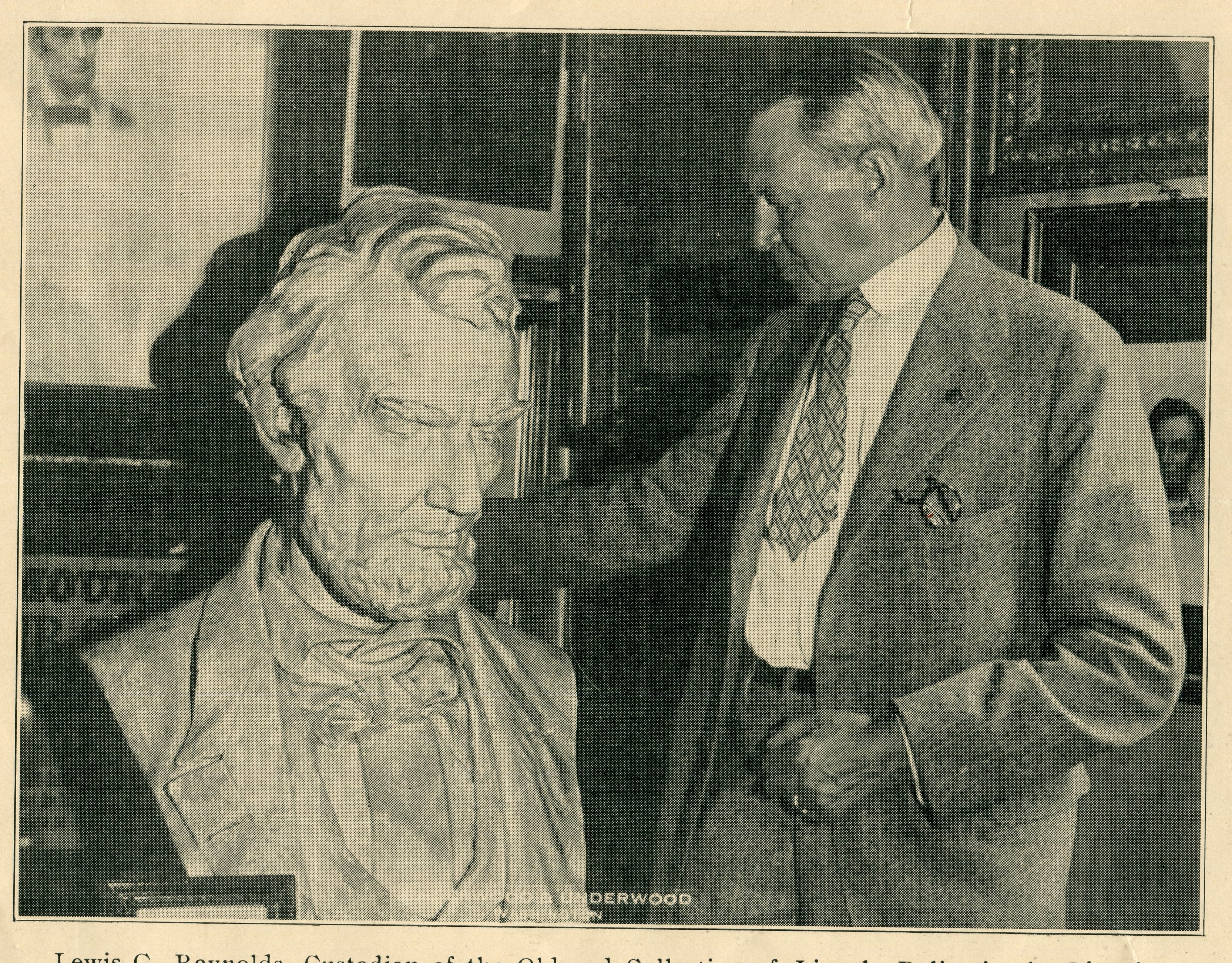

Mr. Reynolds was born at Bellefontaine, Ohio on June 28, 1858 and grew up in Dayton, Ohio. In Dayton, he worked for his father at the Reynolds & Reynolds Co., manufacturing notebooks and other school supplies. Later he started his own company, manufacturing paper cartons and served for 10 years as a member of the school board of that city. While in Ohio, Mr. Reynolds came to know many American leaders, including President McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt and Ohio politicos Myron T. Herrick, and Mark Hannah. In 1896 he married Miss Jeanette Lytle in Dayton. She died in 1903 and in 1909 he married Mary V. Williams of Richmond, Indiana. The couple relocated to Richmond and during World War I, Reynolds was prominent in organizing Liberty Loan drives for the war effort.

Mr. Reynolds was born at Bellefontaine, Ohio on June 28, 1858 and grew up in Dayton, Ohio. In Dayton, he worked for his father at the Reynolds & Reynolds Co., manufacturing notebooks and other school supplies. Later he started his own company, manufacturing paper cartons and served for 10 years as a member of the school board of that city. While in Ohio, Mr. Reynolds came to know many American leaders, including President McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt and Ohio politicos Myron T. Herrick, and Mark Hannah. In 1896 he married Miss Jeanette Lytle in Dayton. She died in 1903 and in 1909 he married Mary V. Williams of Richmond, Indiana. The couple relocated to Richmond and during World War I, Reynolds was prominent in organizing Liberty Loan drives for the war effort.

The Reynolds leaflet further reveals,”Father and mother were at Ford’s Theatre the night of the assassination, and although it was late when they returned home, the general excitement of the night had reached our neighborhood. The newsboys shrill cries of “Extra! Extra! President Lincoln Shot” had awakened everybody in the boarding house. I, too, was awake. Young as I was, I realized what dreadful thing had happened, and I lay wide-eyed in my little trundle bed while father and mother related to the others their personal story of the tragedy. Father, accompanied by several of the men guests, went back to the scene and did not return until after the fateful hour of 7:22 the next morning. I remember as clearly as though it were of yesterday, wearing a wide band of black around the sleeve of my bright plaid jacket, and, carried in father’s arms, of passing the somber catafalque in the rotunda of the Capitol, which inclosed (sic) all that was mortal of the beloved Lincoln. A few weeks later I witnessed the Grand Review of the Army – that wonderful spectacle of the returning boys in blue – which took several days in its passing.”

The Reynolds leaflet further reveals,”Father and mother were at Ford’s Theatre the night of the assassination, and although it was late when they returned home, the general excitement of the night had reached our neighborhood. The newsboys shrill cries of “Extra! Extra! President Lincoln Shot” had awakened everybody in the boarding house. I, too, was awake. Young as I was, I realized what dreadful thing had happened, and I lay wide-eyed in my little trundle bed while father and mother related to the others their personal story of the tragedy. Father, accompanied by several of the men guests, went back to the scene and did not return until after the fateful hour of 7:22 the next morning. I remember as clearly as though it were of yesterday, wearing a wide band of black around the sleeve of my bright plaid jacket, and, carried in father’s arms, of passing the somber catafalque in the rotunda of the Capitol, which inclosed (sic) all that was mortal of the beloved Lincoln. A few weeks later I witnessed the Grand Review of the Army – that wonderful spectacle of the returning boys in blue – which took several days in its passing.”

Two decades later, in 1960, the Richmond Palladium-Item newspaper profiled the widow of the former curator, offering new insight. The article is titled: “Local Woman Conducted Tours In House Where Lincoln Died.” It reveals, “Mrs. Reynolds and her husband lived on the second floor of the house at 516 Tenth street, Washington, DC, at the time Mr. Reynolds was curator of the Oldroyd Lincoln Memorial collection. This was from 1928 through 1936. “I never heard anyone ask Mr. Reynolds a question about Mr. Lincoln he could not answer,” Mrs. Reynolds recalls. Her husband acquired the job as curator when he heard Oldroyd wanted to retire… “I have had visitors say to me doesn’t it give you a creepy feeling?” (sleeping in the house where Lincoln died.) Her answer was always “No.” To the reporter, she said, “I never had a creepy feeling. When I thought about it, it was just a feeling of awe and reverence.” Mr. Reynolds described the collection via radio from the Petersen house several times.”

Two decades later, in 1960, the Richmond Palladium-Item newspaper profiled the widow of the former curator, offering new insight. The article is titled: “Local Woman Conducted Tours In House Where Lincoln Died.” It reveals, “Mrs. Reynolds and her husband lived on the second floor of the house at 516 Tenth street, Washington, DC, at the time Mr. Reynolds was curator of the Oldroyd Lincoln Memorial collection. This was from 1928 through 1936. “I never heard anyone ask Mr. Reynolds a question about Mr. Lincoln he could not answer,” Mrs. Reynolds recalls. Her husband acquired the job as curator when he heard Oldroyd wanted to retire… “I have had visitors say to me doesn’t it give you a creepy feeling?” (sleeping in the house where Lincoln died.) Her answer was always “No.” To the reporter, she said, “I never had a creepy feeling. When I thought about it, it was just a feeling of awe and reverence.” Mr. Reynolds described the collection via radio from the Petersen house several times.”

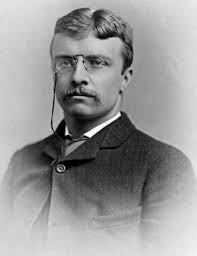

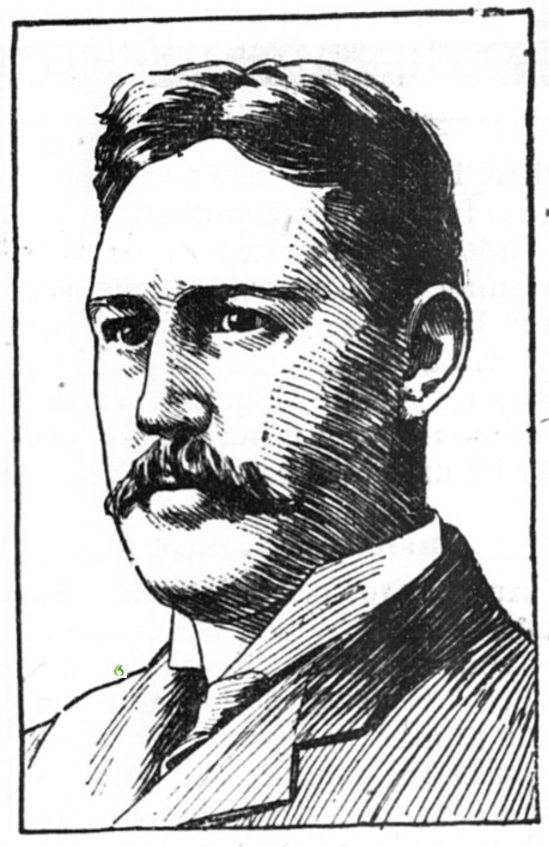

Most Americans remember President William McKinley solely for the way he died. His image a milquetoast chief executive from the age of American Imperialism who was at the helm for the dawn of the 20th century. McKinley’s ordinary appearance belied the fact that he was the last president to have served in the American Civil War and the only one to have started the war as an enlisted soldier. It is long forgotten that McKinley led the nation to victory in the Spanish-American War, protected American industry by raising tariffs and kept the nation on the gold standard by rejecting free silver. Most notably, his assassination at the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York unleashed the central figure who would come to personify the new century; his Vice-President Teddy Roosevelt.

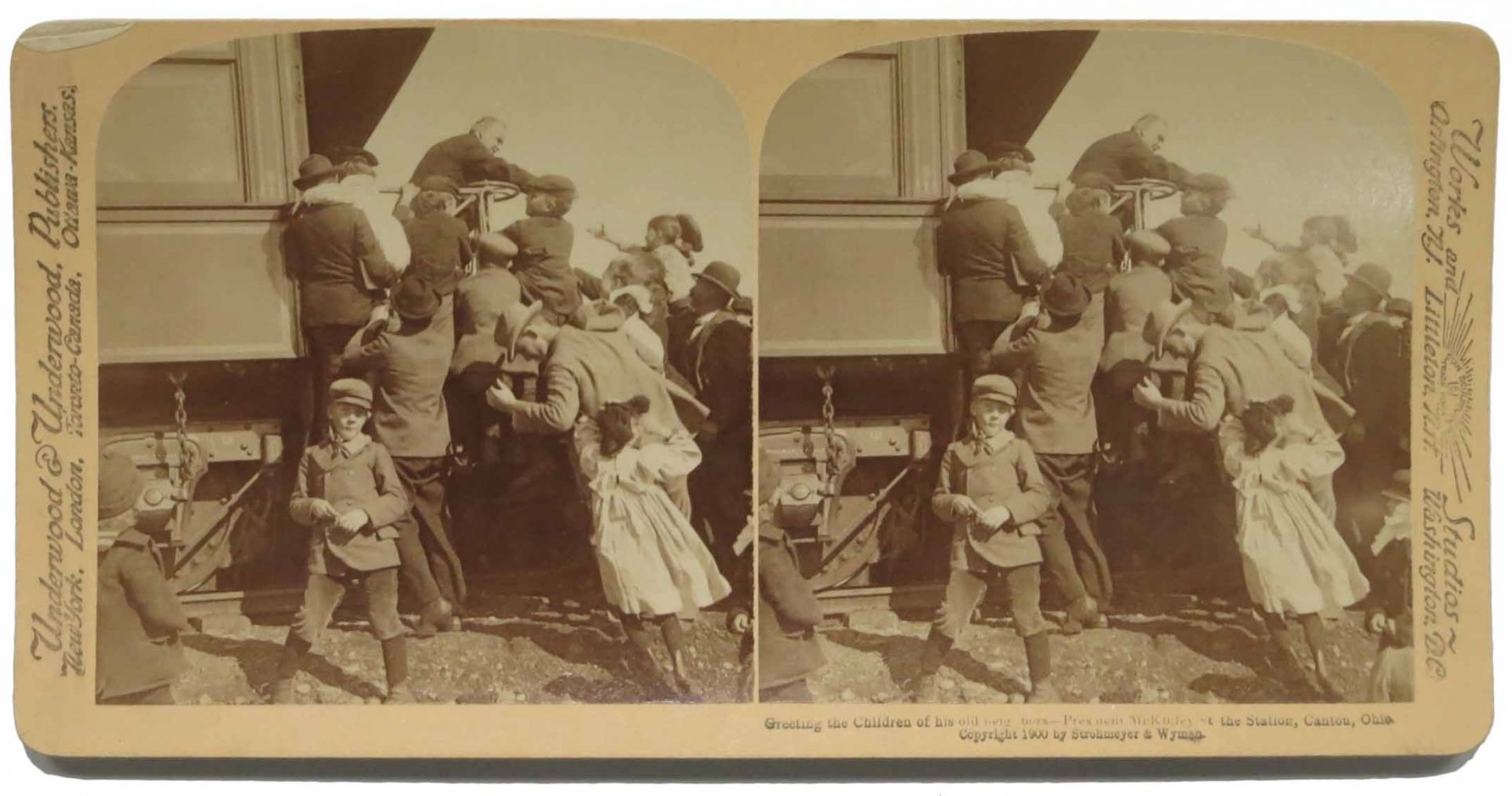

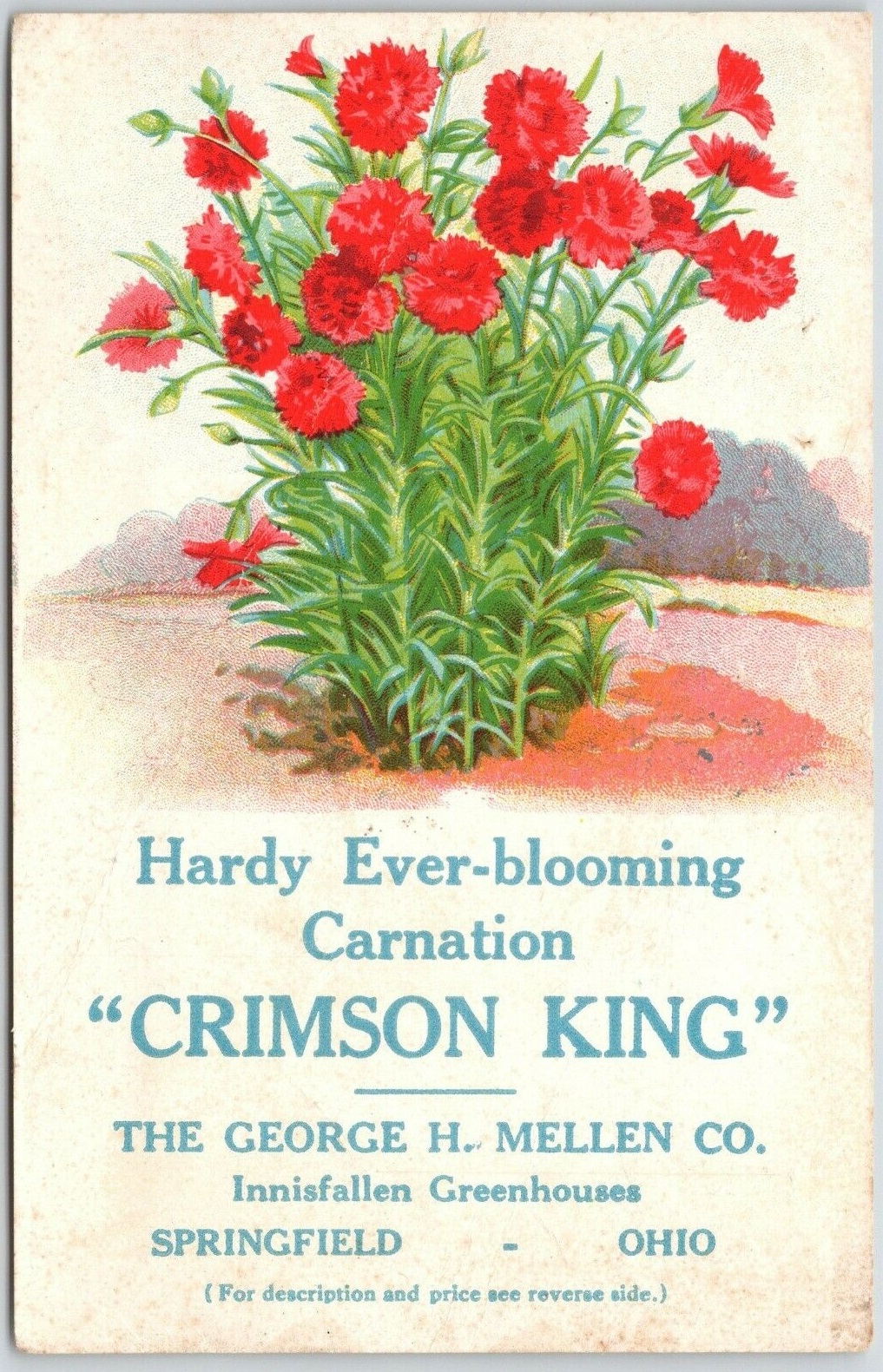

Most Americans remember President William McKinley solely for the way he died. His image a milquetoast chief executive from the age of American Imperialism who was at the helm for the dawn of the 20th century. McKinley’s ordinary appearance belied the fact that he was the last president to have served in the American Civil War and the only one to have started the war as an enlisted soldier. It is long forgotten that McKinley led the nation to victory in the Spanish-American War, protected American industry by raising tariffs and kept the nation on the gold standard by rejecting free silver. Most notably, his assassination at the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York unleashed the central figure who would come to personify the new century; his Vice-President Teddy Roosevelt. McKinley’s favorite flower was a red carnation. He displayed his affection by wearing one of the bright red florets in his lapel everyday. The carnation boutonnière soon became McKinley’s personal trademark. As President, bud vases filled with red carnations were conspicuously placed around the White House (known as the “Executive Mansion” back then). Whenever a guest visited the President, McKinley’s custom was to remove the carnation from his lapel and present it to the star struck visitor. For men, he would often place the souvenir blossom into the lapel himself and suggest that it be given to an absent wife, mother or child. Afterwards, he would replace his boutonnière with another from a nearby vase and repeat the transfer again-and-again for the rest of the day. McKinley was superstitious about these carnations, believing that they brought good luck to both him and his recipient.

McKinley’s favorite flower was a red carnation. He displayed his affection by wearing one of the bright red florets in his lapel everyday. The carnation boutonnière soon became McKinley’s personal trademark. As President, bud vases filled with red carnations were conspicuously placed around the White House (known as the “Executive Mansion” back then). Whenever a guest visited the President, McKinley’s custom was to remove the carnation from his lapel and present it to the star struck visitor. For men, he would often place the souvenir blossom into the lapel himself and suggest that it be given to an absent wife, mother or child. Afterwards, he would replace his boutonnière with another from a nearby vase and repeat the transfer again-and-again for the rest of the day. McKinley was superstitious about these carnations, believing that they brought good luck to both him and his recipient. One account alleges that McKinley’s “Genus Dianthus” custom began early in his presidency when an aide brought his two sons to the White House to meet the President. McKinley, who loved children dearly, presented his carnation to the older boy. Seeing the disappointment in the younger boy’s face, the President deftly retrieved a replacement carnation and pinned it on his own lapel. Here the flower remained for a few moments before he removed it and gave to the younger child, explaining “this way you both can have a carnation worn by the President.”

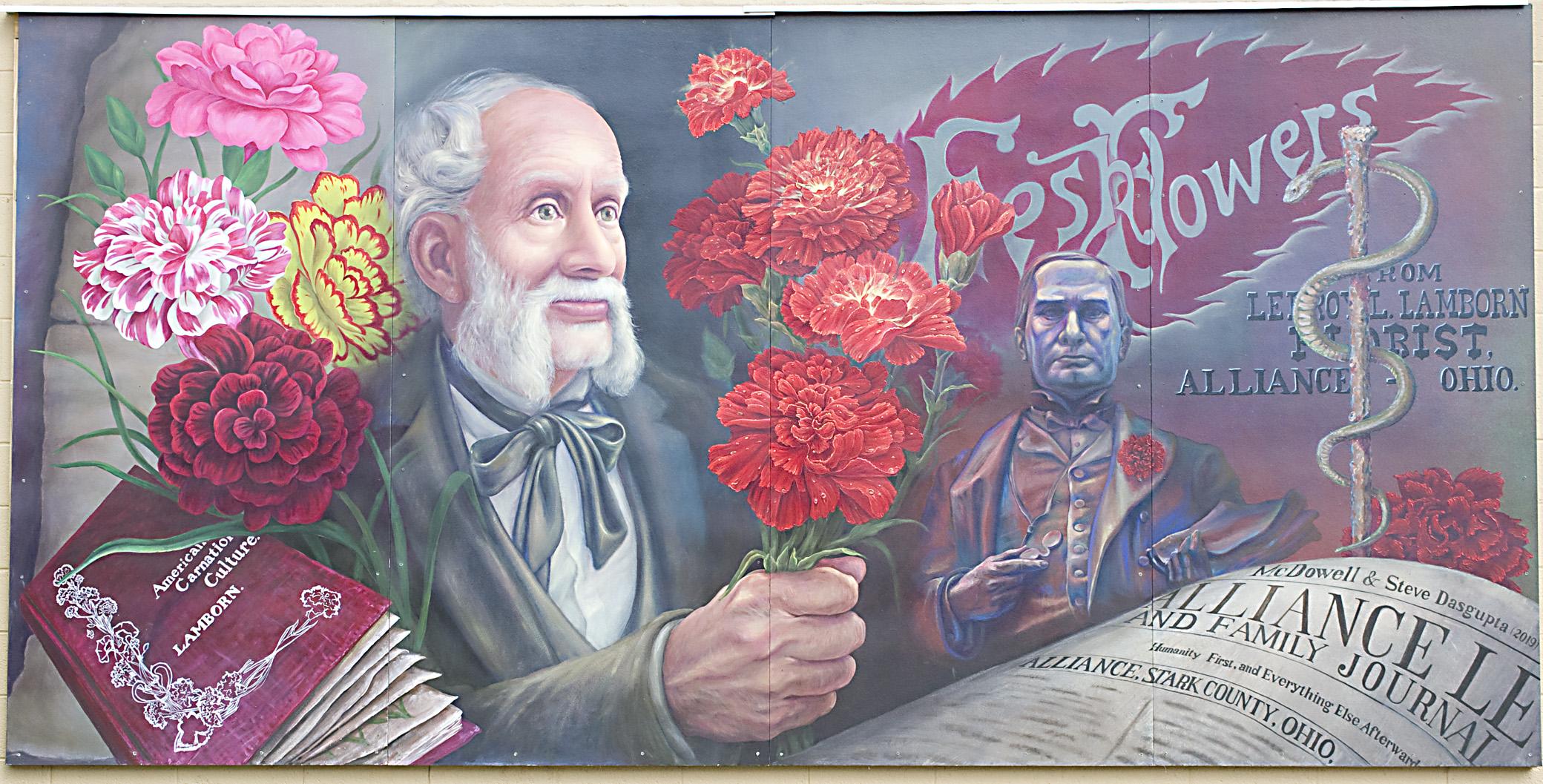

One account alleges that McKinley’s “Genus Dianthus” custom began early in his presidency when an aide brought his two sons to the White House to meet the President. McKinley, who loved children dearly, presented his carnation to the older boy. Seeing the disappointment in the younger boy’s face, the President deftly retrieved a replacement carnation and pinned it on his own lapel. Here the flower remained for a few moments before he removed it and gave to the younger child, explaining “this way you both can have a carnation worn by the President.” However, McKinley’s ubiquitous floral tradition can be traced to the election of 1876, when he was running for a seat in Congress. His opponent, Dr. Levi Lamborn, of Alliance, Ohio, was an accomplished amateur horticulturist famed for developing a strain of vivid scarlet carnations he dubbed “Lamborn Red.” Dr. Lamborn presented McKinley with a “Lamborn Red” boutonniere before their debates. After he won the election, McKinley viewed the red carnation as a good luck charm. He wore one on his lapel regularly and soon began his custom of presenting them to visitors. He wore one during his fourteen years in Congress, his two gubernatorial wins and both 1896 and 1900 presidential campaigns.

However, McKinley’s ubiquitous floral tradition can be traced to the election of 1876, when he was running for a seat in Congress. His opponent, Dr. Levi Lamborn, of Alliance, Ohio, was an accomplished amateur horticulturist famed for developing a strain of vivid scarlet carnations he dubbed “Lamborn Red.” Dr. Lamborn presented McKinley with a “Lamborn Red” boutonniere before their debates. After he won the election, McKinley viewed the red carnation as a good luck charm. He wore one on his lapel regularly and soon began his custom of presenting them to visitors. He wore one during his fourteen years in Congress, his two gubernatorial wins and both 1896 and 1900 presidential campaigns.

After his second inauguration on March 4, 1901, William and Ida McKinley departed on a six-week train trip of the country. The McKinleys’ were to travel through the South to the Southwest, and then up the Pacific coast and back east again, to conclude with a visit to the Buffalo Exposition on June 13, 1901. However, the First Lady fell ill in California, causing her husband to limit his public events and cancel a series of planned speeches. The First family retreated to Washington for a month and then traveled to their Canton, Ohio home for another two months, delaying the Expo trip until September.

After his second inauguration on March 4, 1901, William and Ida McKinley departed on a six-week train trip of the country. The McKinleys’ were to travel through the South to the Southwest, and then up the Pacific coast and back east again, to conclude with a visit to the Buffalo Exposition on June 13, 1901. However, the First Lady fell ill in California, causing her husband to limit his public events and cancel a series of planned speeches. The First family retreated to Washington for a month and then traveled to their Canton, Ohio home for another two months, delaying the Expo trip until September.

Loyal readers will recognize my affinity for objects and will not be surprised by the query, “What became of that assassination carnation?” In an article for the Massillon, Ohio Daily Independent newspaper on Sept. 7, 1984, Myrtle Ledger Krass, the 12-year-old-girl to whom the President gave his lucky flower to moments before he was killed, reported that the McKinley’s carnation was pressed and kept in the family Bible. Myrtle, at the time a well-known painter living in Largo, Florida, explained how, many years later while moving, “The old Bible had been put away for years, when I took it out to wrap it for moving, it just crumbled in my hand. Just fell away to nothing.”

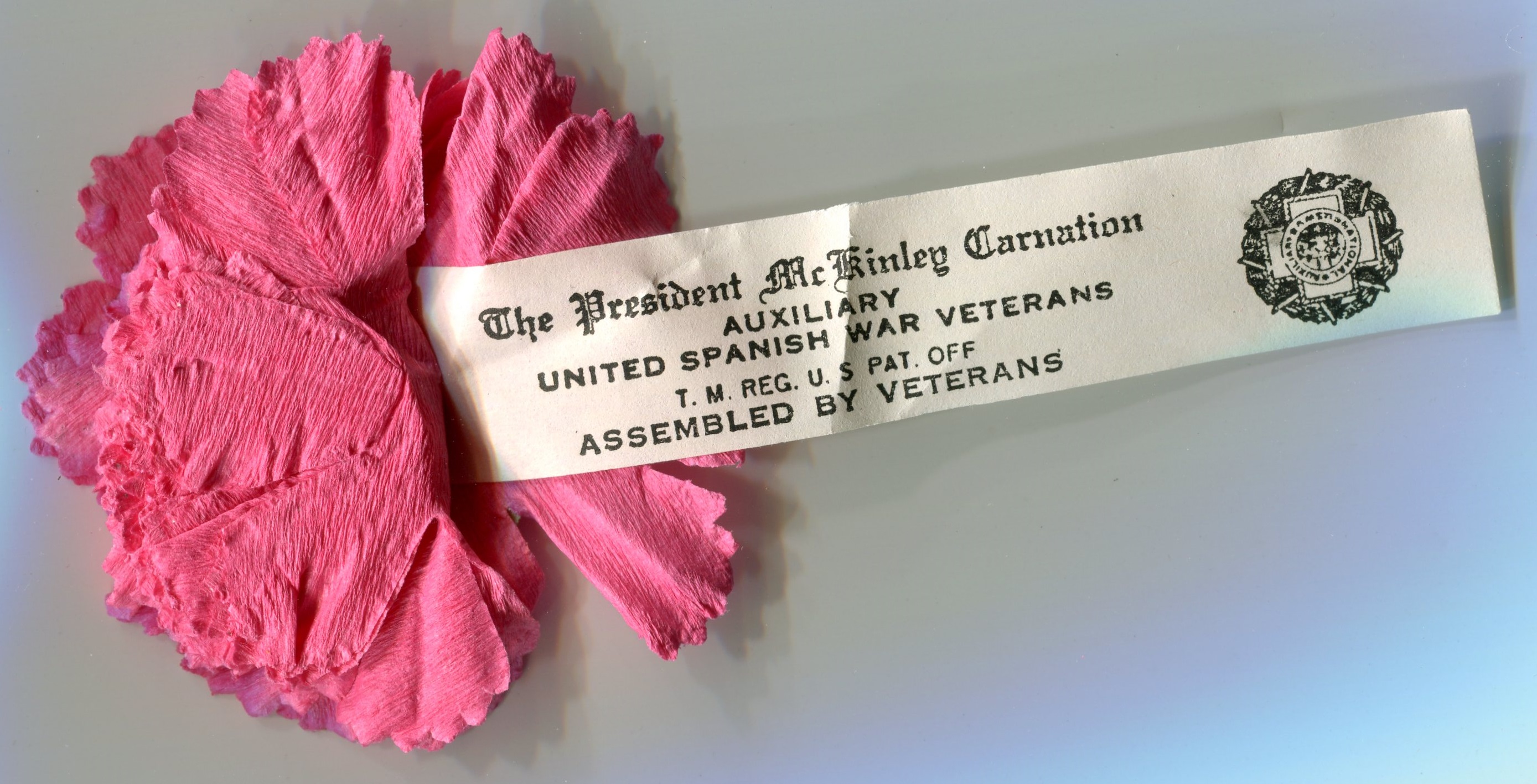

Loyal readers will recognize my affinity for objects and will not be surprised by the query, “What became of that assassination carnation?” In an article for the Massillon, Ohio Daily Independent newspaper on Sept. 7, 1984, Myrtle Ledger Krass, the 12-year-old-girl to whom the President gave his lucky flower to moments before he was killed, reported that the McKinley’s carnation was pressed and kept in the family Bible. Myrtle, at the time a well-known painter living in Largo, Florida, explained how, many years later while moving, “The old Bible had been put away for years, when I took it out to wrap it for moving, it just crumbled in my hand. Just fell away to nothing.” In 1902, Lewis Gardner Reynolds (born in 1858 in Bellefontaine, Ohio) found himself in Buffalo on business on the first anniversary of McKinley’s death. While there he found that the mayor of Buffalo had declared the day a legal holiday. Gardner recalled, “without thinking at the time that I was doing something that would become a national custom, I purchased a pink carnation which I placed in the button hole of my coat after tying a small piece of black ribbon on it. As I went through Buffalo I explained to questioners the reason for the flower and the black ribbon. Many of those who questioned me followed my example.” On his return to Ohio he explained to his friend Senator Mark Hannah what he had done in Buffalo. Later, in Cleveland, Reynolds met with Hannah and Governor Myron T. Herrick. Soon plans were made to celebrate Jan. 29, the anniversary of McKinley’s birth, as “Carnation Day.”

In 1902, Lewis Gardner Reynolds (born in 1858 in Bellefontaine, Ohio) found himself in Buffalo on business on the first anniversary of McKinley’s death. While there he found that the mayor of Buffalo had declared the day a legal holiday. Gardner recalled, “without thinking at the time that I was doing something that would become a national custom, I purchased a pink carnation which I placed in the button hole of my coat after tying a small piece of black ribbon on it. As I went through Buffalo I explained to questioners the reason for the flower and the black ribbon. Many of those who questioned me followed my example.” On his return to Ohio he explained to his friend Senator Mark Hannah what he had done in Buffalo. Later, in Cleveland, Reynolds met with Hannah and Governor Myron T. Herrick. Soon plans were made to celebrate Jan. 29, the anniversary of McKinley’s birth, as “Carnation Day.”

Today, the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus continues observing Red Carnation Day every January 29 by installing a small display honoring the assassinated President. Last year, the Statehouse Museum Shop and on-site restaurant offered special discounts to anyone wearing a red carnation or dressed in scarlet on that day. Yes, the sentimental association of the carnation with McKinley’s memory is due to Lewis Gardner Reynolds.

Today, the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus continues observing Red Carnation Day every January 29 by installing a small display honoring the assassinated President. Last year, the Statehouse Museum Shop and on-site restaurant offered special discounts to anyone wearing a red carnation or dressed in scarlet on that day. Yes, the sentimental association of the carnation with McKinley’s memory is due to Lewis Gardner Reynolds.

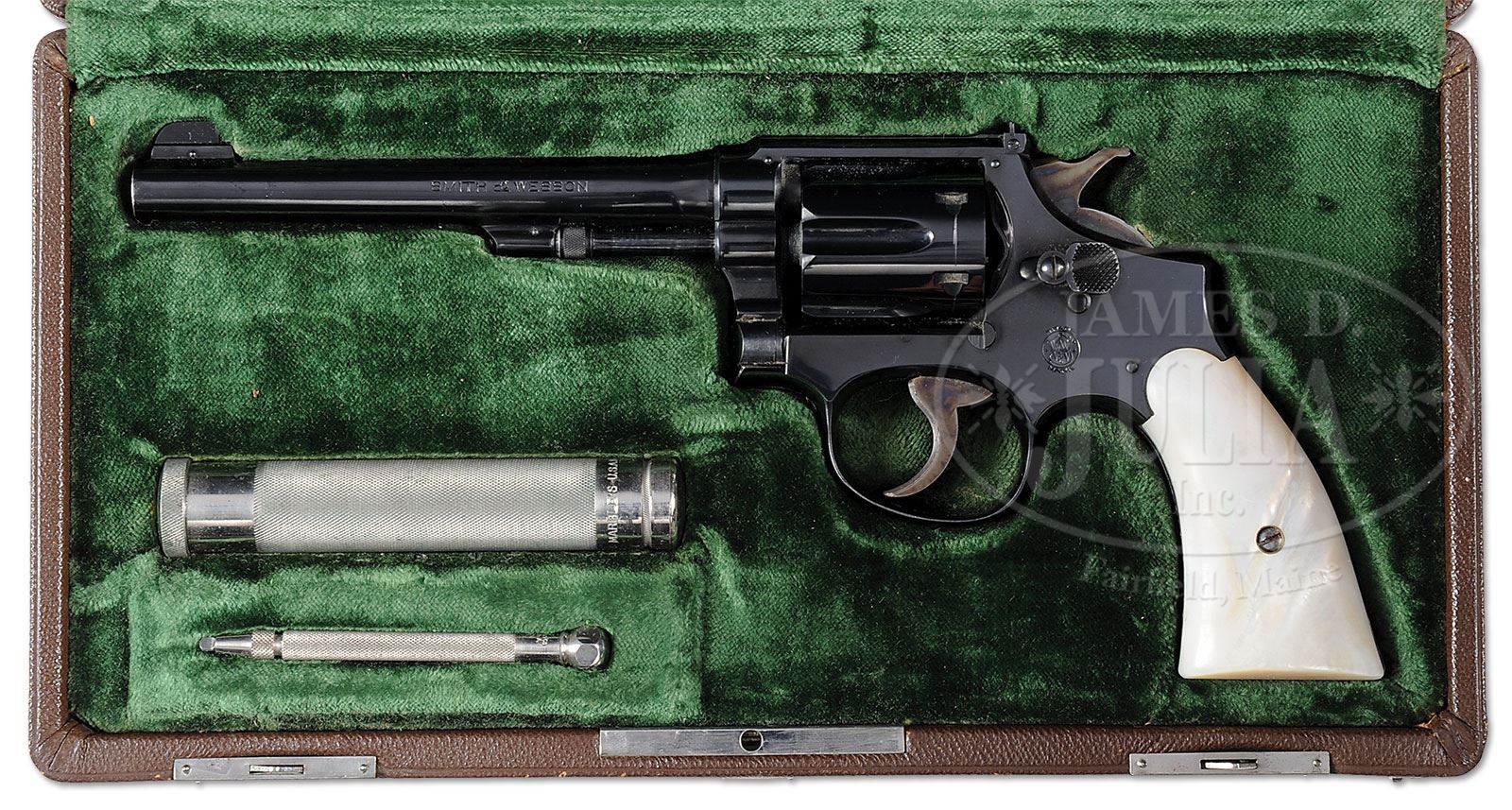

Oh, and by the way, Eleanor Roosevelt, the First lady of the world, icon of liberalism, fighter for civil rights, champion of the poor and marginalized and powerful advocate for women’s rights was a gun owner. Yes, Eleanor Roosevelt, mother of six, grandmother to twenty, was packing heat. Her application for a pistol permit in New York’s Dutchess County can be found at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in Hyde Park. With debate raging around the nation about gun control and Second Amendment rights, the fact that one of the icons of the Democratic womanhood not only owned a gun, but carried it for protection, may come as a surprise.

Oh, and by the way, Eleanor Roosevelt, the First lady of the world, icon of liberalism, fighter for civil rights, champion of the poor and marginalized and powerful advocate for women’s rights was a gun owner. Yes, Eleanor Roosevelt, mother of six, grandmother to twenty, was packing heat. Her application for a pistol permit in New York’s Dutchess County can be found at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in Hyde Park. With debate raging around the nation about gun control and Second Amendment rights, the fact that one of the icons of the Democratic womanhood not only owned a gun, but carried it for protection, may come as a surprise.

The application was processed by the Dutchess County Sheriff’s Office and signed by then-Sheriff C. Fred Close. It included a photo of Eleanor Roosevelt wearing a hat, fur stole and double strand of pearls. The reason for the pistol, according to Eleanor Roosevelt’s application, was “protection.” The timing of the pistol permit coincided with Eleanor Roosevelt’s travels throughout the South-by herself-in advocacy of civil rights. Those trips prompted death threats.

The application was processed by the Dutchess County Sheriff’s Office and signed by then-Sheriff C. Fred Close. It included a photo of Eleanor Roosevelt wearing a hat, fur stole and double strand of pearls. The reason for the pistol, according to Eleanor Roosevelt’s application, was “protection.” The timing of the pistol permit coincided with Eleanor Roosevelt’s travels throughout the South-by herself-in advocacy of civil rights. Those trips prompted death threats. Viewed from the perspective of 21st century politics, where Republicans and Democrats have lined up on opposing sides of the gun control debate, Eleanor Roosevelt’s pistol offers a fresh take on the ongoing debate over the rights of gun owners, the Democrats who want to curtail them and the Republicans who want to expand them.

Viewed from the perspective of 21st century politics, where Republicans and Democrats have lined up on opposing sides of the gun control debate, Eleanor Roosevelt’s pistol offers a fresh take on the ongoing debate over the rights of gun owners, the Democrats who want to curtail them and the Republicans who want to expand them.