In 1988, a survey was taken in conjunction with the “Hoosier Celebration” during Governor Robert Orr’s administration ranking the best known Hoosiers. Abraham Lincoln was number one and James Whitcomb Riley was number two followed (in descending order) by Benjamin and William Henry Harrison and explorers Lewis and Clark, who tied with former Governor Otis Bowen. And, because everybody loves a list, others making the cut included Larry Bird, John Cougar Mellencamp, Red Skelton, Florence Henderson, Jane Pauley, Michael Jackson and Bobby Knight. Don’t remember the “Hoosier Celebration”? Neither do I.

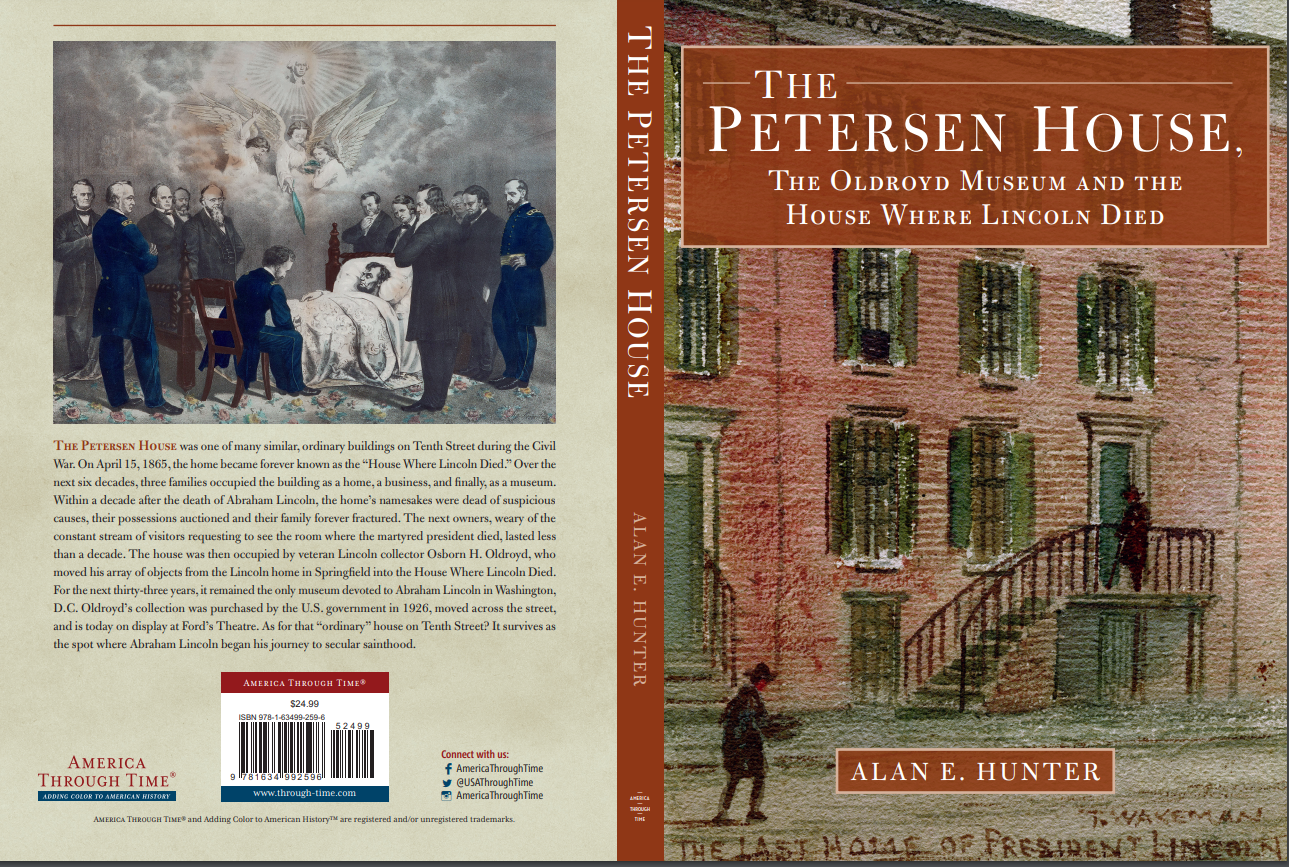

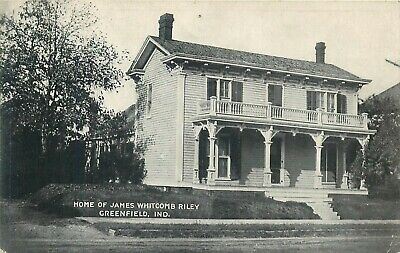

This Saturday (Yay! On Halloween!) October 31st, I will be visiting the James Whitcomb Riley boyhood home in Greenfield to talk about both Lincoln and Riley. That day will be the official book reveal for my newest book, “The Petersen House, The Oldroyd Museum and The House Where Lincoln Died”. Thanks to the courtesy of former Indiana National Road Board member and Director of the Riley Boyhood Home and Museum Stacey Poe, you are invited to come out at 2:00 pm and experience the Riley home and their new “Lizabuth Ann’s Kitchen” facility located at 250 W. Main Street on the historic National Road. I will be bringing some Lincoln props, signing books, sharing stories about the Washington DC building Lincoln died in (and it’s Indiana connection) and, in the “spirit” of the season, spinning a few ghost stories too.

Although Lincoln and Riley died a half-century apart, the men had much in common. The two were considered the state’s most famous Hoosiers (that is until John Dillinger died in 1934) and their names were often linked in speeches, newspaper articles, books and periodicals in the first fifty years of the 20th century. One of my favorite quotes found while searching the virtual stacks of old newspapers comes from the July 20, 1941 Manhattan Kansas Morning Chronicle: “If you want to succeed in life, you might run a better chance if you live in a house with green shutters. Abraham Lincoln, Mark Twain and James Whitcomb Riley all lived in such houses.” Lincoln and Riley epitomized everything that was good about being a Hoosier, right down to the color of their green window shutters.

Although Lincoln and Riley died a half-century apart, the men had much in common. The two were considered the state’s most famous Hoosiers (that is until John Dillinger died in 1934) and their names were often linked in speeches, newspaper articles, books and periodicals in the first fifty years of the 20th century. One of my favorite quotes found while searching the virtual stacks of old newspapers comes from the July 20, 1941 Manhattan Kansas Morning Chronicle: “If you want to succeed in life, you might run a better chance if you live in a house with green shutters. Abraham Lincoln, Mark Twain and James Whitcomb Riley all lived in such houses.” Lincoln and Riley epitomized everything that was good about being a Hoosier, right down to the color of their green window shutters.

Lizabuth Ann’s Kitchen

The comparison was not unfounded. Both men were born in a log cabin. Both came from humble origins. Both were unevenly educated and both men never stopped learning. Both studied law-Lincoln with borrowed law books, Riley doodling poetry in the margins of his father’s law books. Both men were poets and both were considered among the greatest speakers of their generation. And both men had problematic relationships with women. Lincoln once said that he could “never be satisfied with anyone who would be blockhead enough to have me” and Riley famously said “the highest compliment I could pay to a woman is to not marry her.”

Reuben Alexander Riley (1819-1893)

For the poet, his admiration began with his father, Reuben Riley. The senior Riley was a state legislator and among the first central Indiana politicians to embrace the railsplitter as a national figure and presidential candidate. Riley was considered by many to be the best political orator of his day. He traveled the Hoosier state stumping for Lincoln in 1860 and continued his support until the day that Lincoln died. Because of this young J.W. Riley could not remember a time when he did not admire Lincoln.

When the Lincoln funeral train came through Indiana on April 30, 1865, the official “Travel Log” notes that it arrived in Greenfield at 5:48 a.m., Philadelphia at 5:57 a.m., Cumberland at 6:30 a.m., the Engine House (identified as “Thorne” in Irvington) at 6:45 a.m. before finally arriving in Indianapolis at 7:00 a.m. In Greenfield, the depot was choked with people wishing to gaze upon the face of the departed leader one last time. The train was not officially scheduled to stop in Greenfield, but the mood among the citizens was that perhaps the engineer might be persuaded to stop when he witnessed the tremendous outpouring of trackside emotion at the Greenfield depot.

The local newspaper described “a knot of three boys, hands in pockets chattering back and forth with each other while pacing up and down the railroad tracks. Two older fellows were standing together, each arm around the other, probably soldiers remembering what it means to be a comrade.” The depot porch was filled to overflowing with women in their long dresses, old soldiers in their Union uniforms and a sea of men dressed entirely in black. The telegraph operator in Charlottesville wired that the train had just passed and was heading towards the neighboring town. A sentinel was perched atop the station to alert the citizens below of the train’s approach.

In a few moments, a cloud of silver phosphorescent smoke appeared above the tree tops along the route of today’s Pennsy trail. “Here it Comes” was the cry from above and immediately the crowd below hushed and gazed eastward expectantly. For several moments, the only sound that could be heard on the platform was the muffled weeping of the gathered mourners. As the train slowly approached, Captain Reuben Riley read aloud excerpts from Lincoln’s second Inaugural address at the close of which he sat down and wept uncontrollably. The train paused briefly at the station and the engineer removed his cap in respect to reverent gathering. Fortuitously, Reverend Manners stepped from the crowd and led the group in a prayer that began, “Thank God for the life of Abraham Lincoln.” The people now openly wept as the train slowly departed westward towards Indianapolis. It is likely that 16-year-old James Whitcomb Riley was present that day.

Riley wrote two poems dedicated to Abraham Lincoln. in a letter to Edward W. Bok dated October 23, 1890, Riley said this of the sixteenth President; “I think of what a child Lincoln must have been-and the same child-heart at home within his breast when death came by.” Along with all the shared common traits mentioned above, Lincoln and Riley were, and still remain, perhaps foremost, the idol of children everywhere.

Three days after Riley died on July 22, 1916, the Morning Call newspaper in Allentown, Pennsylvania eulogized the poet by saying: “The country has produced poets of more creative power and commanding genius, but none- not even Longfellow, beloved as he was- ever came quite so close to the heart of the mass of the people as the Hoosier Poet, James Whitcomb Riley, who died at Indianapolis on Sunday. He was truly from and of the people as was Lincoln, and in their way, his personality and career are almost as interesting and picturesque as those of the immortal emancipator.”

Elbert Hubbard, founder of the Roycrofters Arts & Crafts community in Aurora, New York, said “Who taught Abraham Lincoln and James Whitcomb Riley how to throw the lariat of their imagination over us, rope us hand and foot and put their brand upon us? God educated them. Yes, that is what I mean, and that is why the American people love them.” Hubbard was a contemporary of Riley’s who, along with his wife, died when the Germans sunk the RMS Lusitania leading to our entry into World War I a year before Riley passed.

However, in my view, what links both men in perpetuity is a shared language. Both men spoke fluent Hoosier. All his life, Lincoln and Riley tended to swallow the ‘g’ sound on words ending with ‘ing’, so a Walking Talking Traveling man become Walkin’, Talken’, Travelin’, man. Lincoln said “warsh” for wash, “poosh” for push, “kin” for can, “airth” for earth, “heered” for for heard, “sot” for sat, “thar” for there, “oral” for oil, “hunnert” for hundred, “feesh” for fish and “Mr. Cheerman” for Mr. Chairman. Likewise, Riley practiced the Hoosier dialect in his printed work, saying “punkin'” for pumpkin, “skwarsh” for squash, “iffin'” for if then and “tarlet” for toilet. Both men peppered their speech with distinctive words like yonder and for schoolin’ both “larned” their lessons and got their “eddication” in fits and spurts.

Both men’s lives came to an end in private houses, not in hospitals. Riley in the Nickum House in Indianapolis’ Lockerbie Square and Lincoln in the Petersen House in Washington, D.C. This Saturday, I will share my favorite ghost story about J.W. Riley (in the Lockerbie house) and while I have no ghost stories to share about The House Where Lincoln Died, I will detail a connection between the two. I will introduce you to the three families who resided there, the last of whom, Osborn Oldroyd, displayed his Lincoln collection of relics and objects for over thirty years before selling it to the United States Government in 1926. That collection is now on display in the basement of Ford’s Theatre. Oldroyd, a thrice-wounded Civil War veteran, collector, curator and author, is perhaps the father of the house museum in America. One of Oldroyd’s books, a compilation of poems entitled, “The Poets’ Lincoln— Tributes In Verse To The Martyred President”, was published in 1915. James Whitcomb Riley’s poem, A Peaceful Life with the name “Lincoln” in parenthesis as a sub-title can be found there on page 31. In Oldroyd’s version, the first line differs from Riley’s original version. Riley’s handwritten original (found today in the archives of the Lilly Library on the Bloomington campus of Indiana University) begins: “Peaceful Life:-toil, duty, rest-“. Oldroyd’s book version begins; “A peaceful life —just toil and rest—.” Interestingly, the Oldroyd version has become the standard. And there you have it. Oldroyd’s influence is subtle, his name largely unknown, yet he stays with us to this day.

Oldroyd, a thrice-wounded Civil War veteran, collector, curator and author, is perhaps the father of the house museum in America. One of Oldroyd’s books, a compilation of poems entitled, “The Poets’ Lincoln— Tributes In Verse To The Martyred President”, was published in 1915. James Whitcomb Riley’s poem, A Peaceful Life with the name “Lincoln” in parenthesis as a sub-title can be found there on page 31. In Oldroyd’s version, the first line differs from Riley’s original version. Riley’s handwritten original (found today in the archives of the Lilly Library on the Bloomington campus of Indiana University) begins: “Peaceful Life:-toil, duty, rest-“. Oldroyd’s book version begins; “A peaceful life —just toil and rest—.” Interestingly, the Oldroyd version has become the standard. And there you have it. Oldroyd’s influence is subtle, his name largely unknown, yet he stays with us to this day.

Original publish date: August 24, 2015

Original publish date: August 24, 2015 Babe and Claire left shortly after the picture started and checked into Memorial Hospital for the last time. Babe Ruth struggled to answer letters and meet with visitors right up until August 15, 1948, barely a year after he graced the diamond of Victory Field in Indianapolis. Babe Ruth died in his sleep at 8:01 p.m. on the evening of on Aug. 16,1948. His last conscious act was to autograph a copy of his autobiography for one of his nurses. It was only after the great man’s death that the newspapers announced the cause of death as “throat cancer”.

Babe and Claire left shortly after the picture started and checked into Memorial Hospital for the last time. Babe Ruth struggled to answer letters and meet with visitors right up until August 15, 1948, barely a year after he graced the diamond of Victory Field in Indianapolis. Babe Ruth died in his sleep at 8:01 p.m. on the evening of on Aug. 16,1948. His last conscious act was to autograph a copy of his autobiography for one of his nurses. It was only after the great man’s death that the newspapers announced the cause of death as “throat cancer”.