Original publish date: January 22, 2019

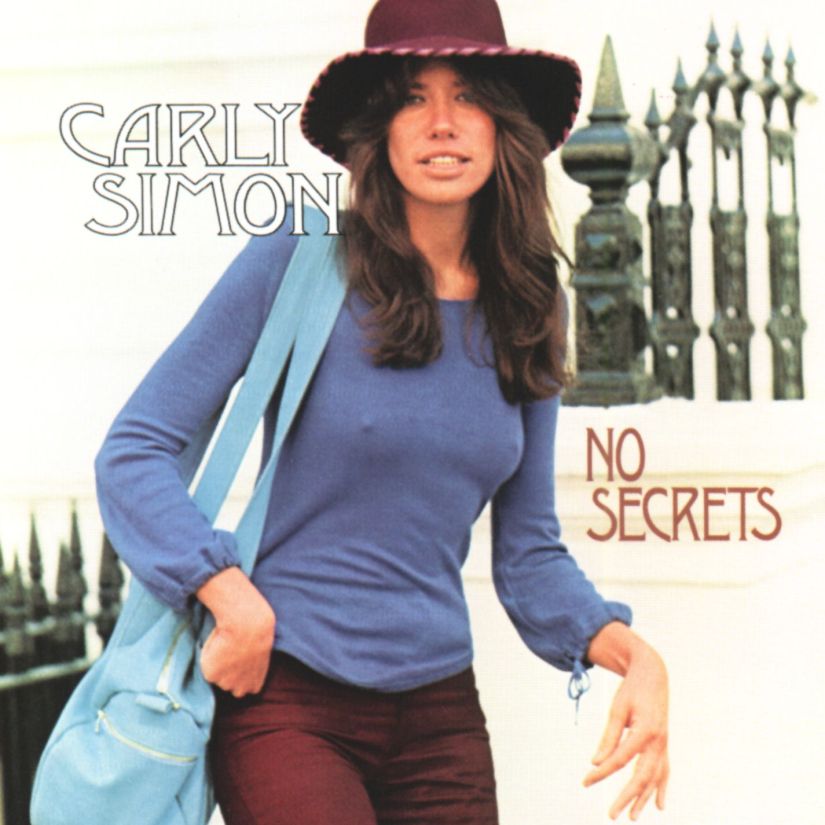

Were you alive on January 22, 1973? If so, consider this a reminder, if not, let me show what a typical day was like for a late-stage Baby Boomer like me. January 22, 1973 was a Monday in the Age of Aquarius. All in the Family was # 1 on television and The Poseidon Adventure was tops at the box office. Carly Simon was riding the top of the charts with her hit song “You’re so vain.” A song that has kept people guessing who she’s singing about to this day. Is it Warren Beatty? Mick Jagger? David Cassidy? Cat Stevens? David Bowie? James Taylor? All of whom have been accused. Carly has never fessed up, although she once admitted that the subject’s name contains the letters A, E, and R.

The month of January 1973 had started on a somber note with memorial services in Washington D.C. for President Harry S Truman on the 5th (he died the day after Christmas 1972). Then, Judge John Sirica began the Nixon impeachment proceedings on the 8th with the trial of seven men accused of committing a ” third rate burglary” of the Democratic Party headquarters at the Watergate. Next came the Inauguration of Richard Nixon (his second) on the 20th. Historians pinpoint Nixon’s speech that day as the end of the “Now Generation” and the beginning of the “Me Generation.” Gone was JFK’s promise of a “New Frontier,” lost was the compassionate feeling of the Civil Rights movement and LBJ’s dream of a “Great Society.” The self-help of the 1960s quickly morphed into the self-gratification of the 1970s, which ultimately devolved into the selfishness of the 1980s.

The line between want and need became hopelessly blurred and remains so to this day.

Twelve years before, John F. Kennedy decreed, “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.” On January 20th, 1973, Richard Nixon, purposely twisted JFK’s inaugural line by declaring , “In our own lives, let each of us ask—not just what will government do for me, but what can I do for myself?” At that moment, the idealism of the sixties gave way to narcissistic self-interest, distrust and cynicism in government of the seventies. Although it had been coming for years, when change finally arrived, it happened so fast that most of us never even noticed.

January 22nd was warm and rainy. It was the first Monday of Nixon’s second term and it would be one for the books. That day, Nixon announced that the war in Vietnam was over. The day before, his National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger and North Vietnamese politburo member Lê Đức Thọ signed off on a treaty that effectively ended the war; on paper that is. The settlement included a cease-fire throughout Vietnam. It addition, the United States agreed to the withdrawal of all U.S. troops and advisers (totaling about 23,700) and the dismantling of all U.S. bases within 60 days. In return, the North Vietnamese agreed to release all U.S. and other prisoners of war. It was agreed that the DMZ at the 17th Parallel would remain a provisional dividing line, with eventual reunification of the country “through peaceful means.”

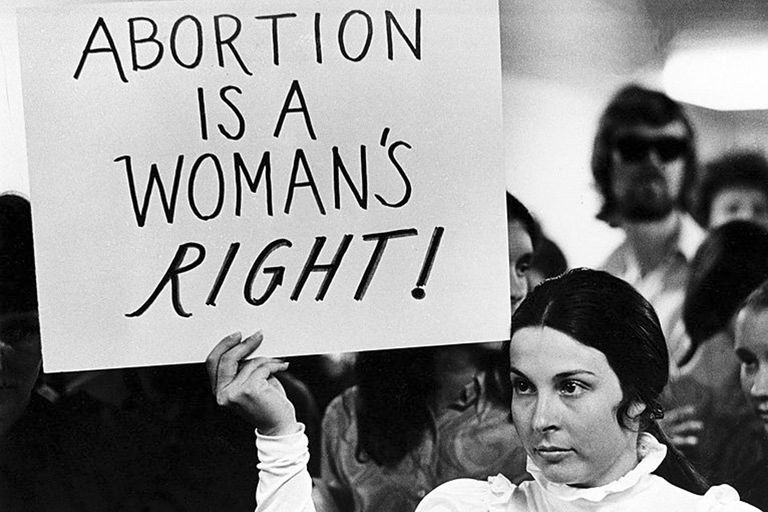

That same day, the United States Supreme Court issued their landmark decision 410 U.S. 113 (1973). Better known as Roe v. Wade. Instantly, the laws of 46 states making abortion illegal were rendered unconstitutional. In a 7-2 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a woman’s right to privacy extended to her right to make her own medical decisions, including having an abortion. The decision legalized abortion by specifically ordering that the states make no laws forbidding it. Rove V. Wade came the same day as the lesser known ruling, Doe v. Bolton, 410 U.S. 179 (1973), which overturned the abortion law of Georgia.

The Georgia law in question permitted abortion only in “cases of rape, severe fetal deformity, or the possibility of severe or fatal injury to the mother.” Other restrictions included the requirement that the procedure be “approved in writing by three physicians and by a three-member special committee that either continued pregnancy would endanger the pregnant woman’s life or “seriously and permanently” injure her health; the fetus would “very likely be born with a grave, permanent and irremediable mental or physical defect”; or the pregnancy resulted from rape or incest.” Only Georgia residents could receive abortions under this statutory scheme: non-residents could not have an abortion in Georgia under any circumstances. The plaintiff, a pregnant woman known as “Mary Doe” in court papers, sued Arthur K. Bolton, then the Attorney General of Georgia, as the official responsible for enforcing the law. The same 7-2 majority that struck down a Texas abortion law in Roe v. Wade, invalidated the Georgia abortion law.

The Roe v. Wade case, filed by “Jane Roe,” challenged a Texas statute that made it a crime to perform an abortion unless a woman’s life was in danger. Roe’s life was not at stake, but she wanted to safely end her pregnancy. The court sided with Roe, saying a woman’s right to privacy “is broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.” Dozens of cases have challenged the decision in Roe v. Wade in the 46 years since the landmark ruling and the echoes of challenge are heard to this day.

And what did Nixon think about that day’s ruling? The same Oval Office taping system that would bring about his downfall in the Watergate Scandal recorded his thoughts on Roe V. Wade for posterity. “I know there are times when abortions are necessary,” he told aide Chuck Colson, “I know that – when you have a black and a white, or a rape. I just say that matter-of-factly, you know what I mean? There are times… Abortions encourage permissiveness. A girl gets knocked up, she doesn’t have to worry about the pill anymore, she goes down to the doctor, wants to get an abortion for five dollars or whatever.” Yep, that was the President of the United States talking. And his day wasn’t even over yet.

At 3:39 p.m. Central Time, former President Lyndon B. Johnson placed a call to his Secret Service agents on the LBJ ranch in Johnson City, Texas. He had just suffered a massive heart attack. The agents rushed into LBJ’s bedroom where they found Johnson lying on the floor still clutching the telephone receiver in his hand. The President was unconscious and not breathing. Johnson was airlifted in one of his own airplanes to Brooke Army General hospital in San Antonio where he was pronounced dead on arrival. Johnson was 64 years old. Shortly after LBJ’s death, his press secretary telephoned Walter Cronkite at CBS who was in the middle of a report on the Vietnam War during his CBS Evening News broadcast. Cronkite abruptly cut his report short and broke the news to the American public.

His death meant that for the first time since 1933, when Calvin Coolidge died during Herbert Hoover’s final months in office, that there were no former Presidents still living; Johnson had been the sole living ex-President Harry S. Truman’s recent death. Johnson had suffered three major heart attacks and, with his heart condition recently diagnosed as terminal, he returned to his ranch to die. He had grown his previously close-cut gray hair down past the back of his neck, his silver curls nearly touching his shoulders. Prophetically, LBJ often told friends that Johnson men died before reaching 65 years old, and he was 64. Had Johnson chosen to run in 1968 (and had he won) his death would have came 2 days after his term ended. As of this 2019 writing, Johnson remains the last former Democratic President to die.

Nixon mentioned all of these events (and more) on his famous tapes. All the President’s men are there to be heard. Along with Colson, Nixon talks with H.R. Haldeman, John Ehrlichman (whom ha calls a “softhead” that day), Bebe Rebozo, Ron Ziegler, and Alexander Haig. Haldeman is the first to inform Nixon of LBJ’s death in “Conversation 036-051” by stating “He’s dead alright.” For his part, Nixon states in “Conversation 036-061” that it makes the “first time in 40 years that there hasn’t been a former President. Hoover lived through all of 40 years” and then refers to the recent peace treaty, “In any event It’ll make him (LBJ) look better in the end than he would have looked otherwise, so… The irony that he died before we got something down there. The strange twists and turns that life takes.”

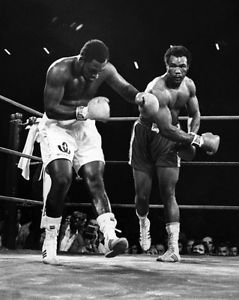

Another event took place that night to round out the day, but unlike the others, you won’t find mention of it on the Nixon tapes. In Jamaica, a matchup of two undefeated heavyweight legends took place. Undisputed world heavyweight champion Smokin’ Joe Frazier (29-0) took on the number one ranked heavyweight challenger George Foreman (37-0) in Jamaica’s National Stadium. Foreman dominated Frazier by scoring six knockdowns in less than two rounds. Foreman scored a technical knockout at 1:35 of the second round to dethrone Frazier and become the new undisputed heavyweight champion (the third-youngest in history after Floyd Patterson and Cassius Clay). This was the fight where ABC’s television broadcaster Howard Cosell made the legendary exclamation, “Down goes Frazier! Down goes Frazier! Down goes Frazier!”

“This is a peace that lasts, and a peace that heals.” Nixon announced to the American people the next day. The announcement came exactly 11 years, one month and one day after the first American death in the Vietnam conflict: 25-year-old Army Specialist 4th Class James Thomas Davis of Livingston, Tenn., who had been killed in an ambush by the Viet Cong outside of Saigon on Dec. 22, 1961. For you budding numerologists out there, that translates to 11-1-1. It was all downhill from there. LBJ’s death precipitated the cancellation of several Inauguration events and a week later, on January 30, former Nixon aides G. Gordon Liddy, James W. McCord Jr. and five others were convicted of conspiracy, burglary and wiretapping in the Watergate incident. The dominoes were falling and eventually “Down goes Nixon! Down goes Nixon!”

Because Pavlick didn’t get near Kennedy on the day he was arrested, the story was not immediate national news. The story of Pavlick’s arrest happened the same day as a terrible airline disaster, known as the TWA Park Slope Plane Crash, in which two commercial planes collided over New York City, killing 134 people (including 6 on the ground). The plane crash story, the worst air disaster in U.S. history up to that time, occupied the national headlines and led the television and radio newscasts.

Because Pavlick didn’t get near Kennedy on the day he was arrested, the story was not immediate national news. The story of Pavlick’s arrest happened the same day as a terrible airline disaster, known as the TWA Park Slope Plane Crash, in which two commercial planes collided over New York City, killing 134 people (including 6 on the ground). The plane crash story, the worst air disaster in U.S. history up to that time, occupied the national headlines and led the television and radio newscasts. On January 27, 1961, a week after Kennedy was inaugurated as the 35th President of the United States, Pavlick was committed to the United States Public Health Service mental hospital in Springfield, Missouri. He was indicted for threatening Kennedy’s life seven weeks later. The case would drag on for years without resolution. Belmont Postmaster Thomas M. Murphy had been promised that he would remain an anonymous informant, but was quickly identified as the tipster by the media. At first he was hailed as a hero and his boss, the Postmaster General, commended his actions. Congress even passed a resolution praising him. But then, fervent right wing publisher William Loeb of the Manchester Union Leader, New Hampshire’s influential state-wide newspaper, began defending Pavlick. Turns out, Loeb held many of the same opinions about Kennedy as the would-be assassin.

On January 27, 1961, a week after Kennedy was inaugurated as the 35th President of the United States, Pavlick was committed to the United States Public Health Service mental hospital in Springfield, Missouri. He was indicted for threatening Kennedy’s life seven weeks later. The case would drag on for years without resolution. Belmont Postmaster Thomas M. Murphy had been promised that he would remain an anonymous informant, but was quickly identified as the tipster by the media. At first he was hailed as a hero and his boss, the Postmaster General, commended his actions. Congress even passed a resolution praising him. But then, fervent right wing publisher William Loeb of the Manchester Union Leader, New Hampshire’s influential state-wide newspaper, began defending Pavlick. Turns out, Loeb held many of the same opinions about Kennedy as the would-be assassin. Loeb very publicly protested that Pavlick was being persecuted and denied his sixth amendment right to a speedy trial. Loeb’s newspaper disputed the insanity ruling and insisted the defendant have his day in court. Once the newspaper took up Pavlick’s cause, Murphy and his family began receiving hate mail, death threats and anonymous phone calls at all hours of the day and night accusing him of helping to frame Pavlick and for “railroading an innocent man.” The abuse continued for years after Murphy’s November 14, 2002 death at age 76. Even today, the surviving Murphy children are targeted by right-wing groups whenever the case gets a new round of public attention.

Loeb very publicly protested that Pavlick was being persecuted and denied his sixth amendment right to a speedy trial. Loeb’s newspaper disputed the insanity ruling and insisted the defendant have his day in court. Once the newspaper took up Pavlick’s cause, Murphy and his family began receiving hate mail, death threats and anonymous phone calls at all hours of the day and night accusing him of helping to frame Pavlick and for “railroading an innocent man.” The abuse continued for years after Murphy’s November 14, 2002 death at age 76. Even today, the surviving Murphy children are targeted by right-wing groups whenever the case gets a new round of public attention. In today’s 24-hour-a-day, scandal-driven media environment, it is hard to believe that an incident of this magnitude would go unnoticed. Or would it? Sure, we all know about the very public assassination threats and attempts once they are out in the open. But what about those threats that are never reported? In Pavlick’s case, the public learned about it from the would-be assassin himself. He was proud of his plans and, after capture, boasted about it to anyone that came within earshot. The answer can be found in the name of the organization protecting the President: The Secret Service is, well, secret.

In today’s 24-hour-a-day, scandal-driven media environment, it is hard to believe that an incident of this magnitude would go unnoticed. Or would it? Sure, we all know about the very public assassination threats and attempts once they are out in the open. But what about those threats that are never reported? In Pavlick’s case, the public learned about it from the would-be assassin himself. He was proud of his plans and, after capture, boasted about it to anyone that came within earshot. The answer can be found in the name of the organization protecting the President: The Secret Service is, well, secret.

nowhere. He lived alone and had no family to speak of. Locals in his hometown of Belmont remember him for his angry political rants and public outbursts at local public meetings. After accusing the town of poisoning his water, Pavlick once confronted the local water company supervisor with a gun, which was then promptly confiscated. His central complaint was that the American flag was not being displayed appropriately. He often criticized the government and blamed most of the country’s problems on the Catholics. But the perpetually grumpy, prune-faced Pavlick focused most of his anger on the Kennedy family and their “undeserved” wealth.

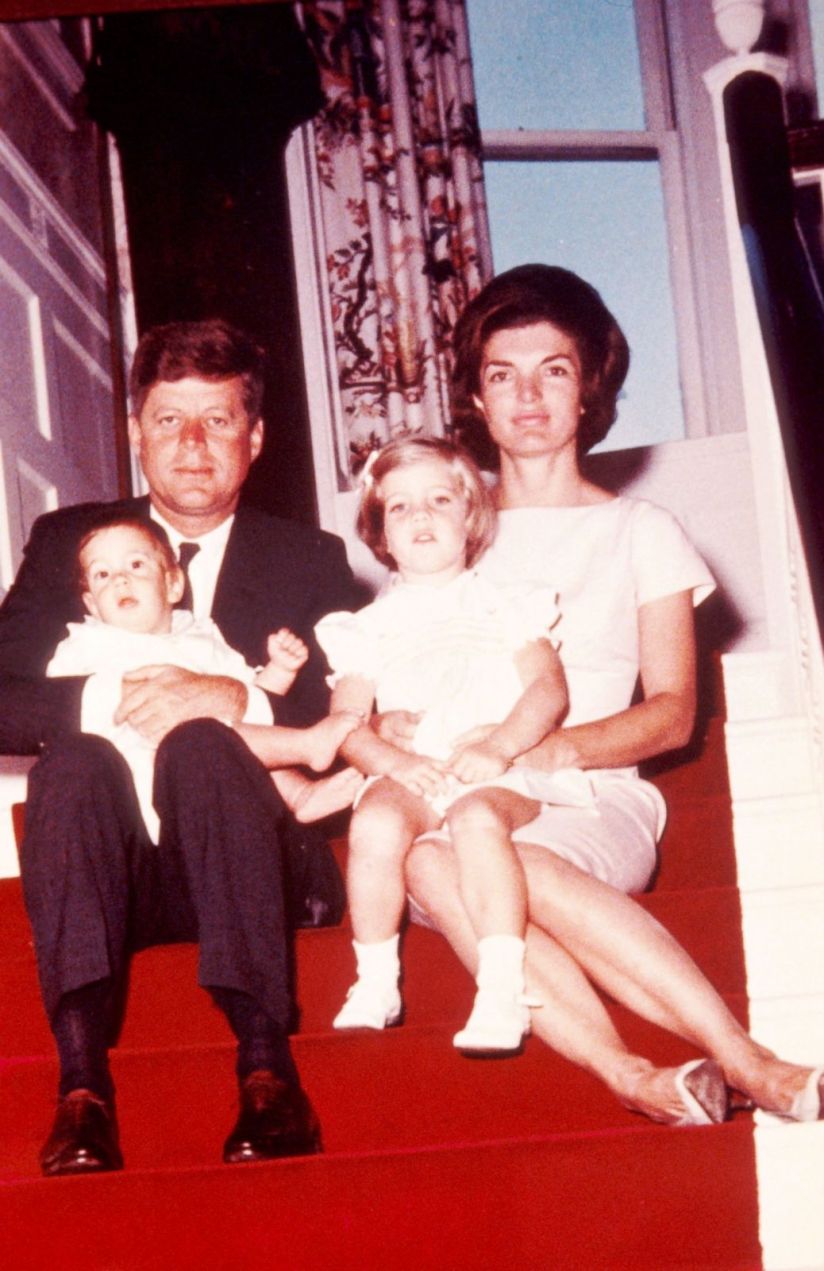

nowhere. He lived alone and had no family to speak of. Locals in his hometown of Belmont remember him for his angry political rants and public outbursts at local public meetings. After accusing the town of poisoning his water, Pavlick once confronted the local water company supervisor with a gun, which was then promptly confiscated. His central complaint was that the American flag was not being displayed appropriately. He often criticized the government and blamed most of the country’s problems on the Catholics. But the perpetually grumpy, prune-faced Pavlick focused most of his anger on the Kennedy family and their “undeserved” wealth. Luckily for Mr. Kennedy, fate stepped in to save the day… and the President-elect’s life. Kennedy did not leave his house alone that morning. Much to Pavlick’s surprise, JFK opened the door holding the hand of his 3-year-old daughter Caroline alongside his wife, Jacqueline who was holding the couple’s newborn son John, Jr., less than a month old. While Pavlick hated John F. Kennedy, he hadn’t signed up to kill Kennedy’s family. So Pavlick eased his itchy trigger-finger off the detonator switch and let the Kennedy limousine glide harmlessly past his car. No one realized that the beat-up old Buick and the white haired old man in it was literally a ticking time bomb. Pavlick glared at the car as it slipped away and decided he would try again another day. Luckily, he never got a second chance.

Luckily for Mr. Kennedy, fate stepped in to save the day… and the President-elect’s life. Kennedy did not leave his house alone that morning. Much to Pavlick’s surprise, JFK opened the door holding the hand of his 3-year-old daughter Caroline alongside his wife, Jacqueline who was holding the couple’s newborn son John, Jr., less than a month old. While Pavlick hated John F. Kennedy, he hadn’t signed up to kill Kennedy’s family. So Pavlick eased his itchy trigger-finger off the detonator switch and let the Kennedy limousine glide harmlessly past his car. No one realized that the beat-up old Buick and the white haired old man in it was literally a ticking time bomb. Pavlick glared at the car as it slipped away and decided he would try again another day. Luckily, he never got a second chance.

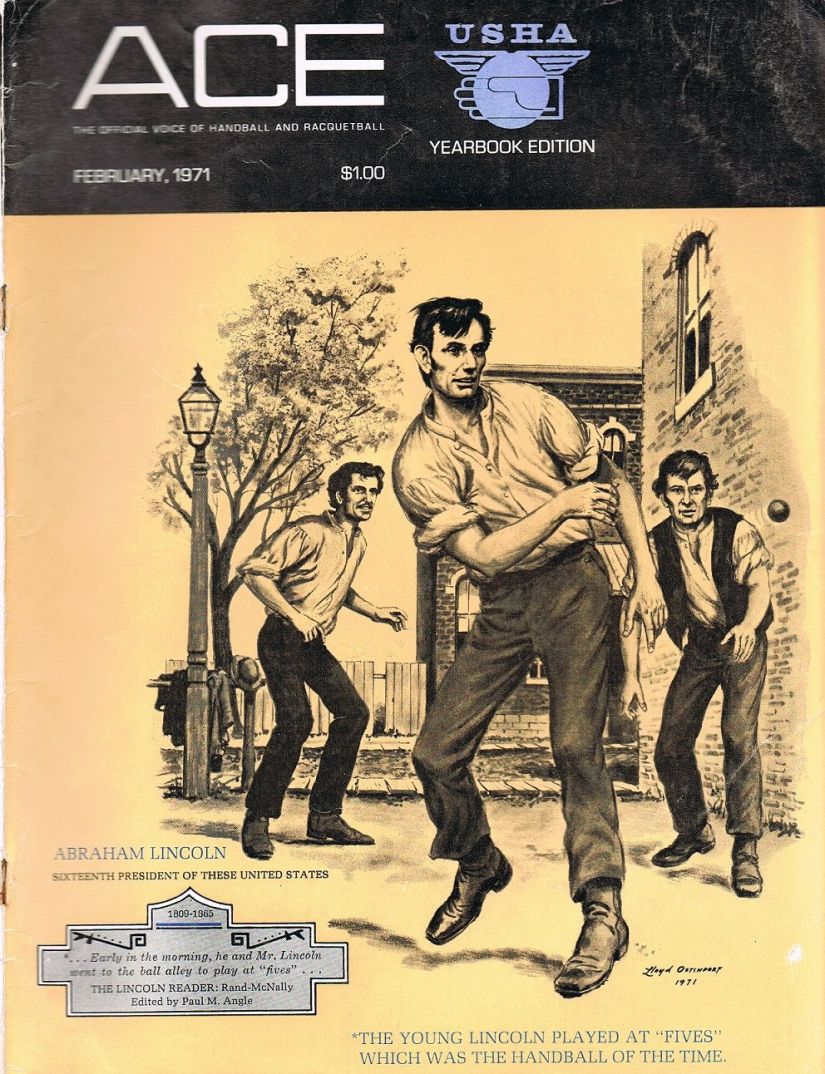

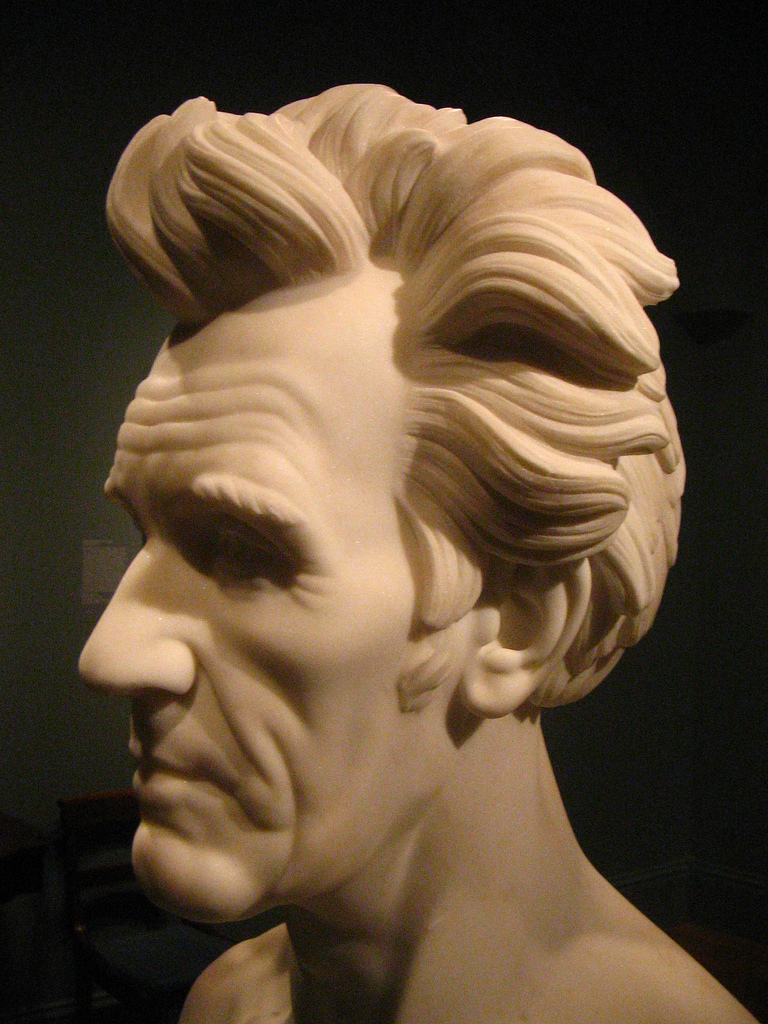

Likewise, you may have heard that he was a handball player, as have I, but details have always been hard to find. The game of handball was much better suited to Lincoln. At 6 feet 4 inches tall, his long legs and gangly arms served the rail splitter well. Muscles honed while wielding an axe as a youth were kept tight and toned as an adult. Lincoln milked his own cows and chopped his own wood even though he was a successful, affluent lawyer with little time to spare.

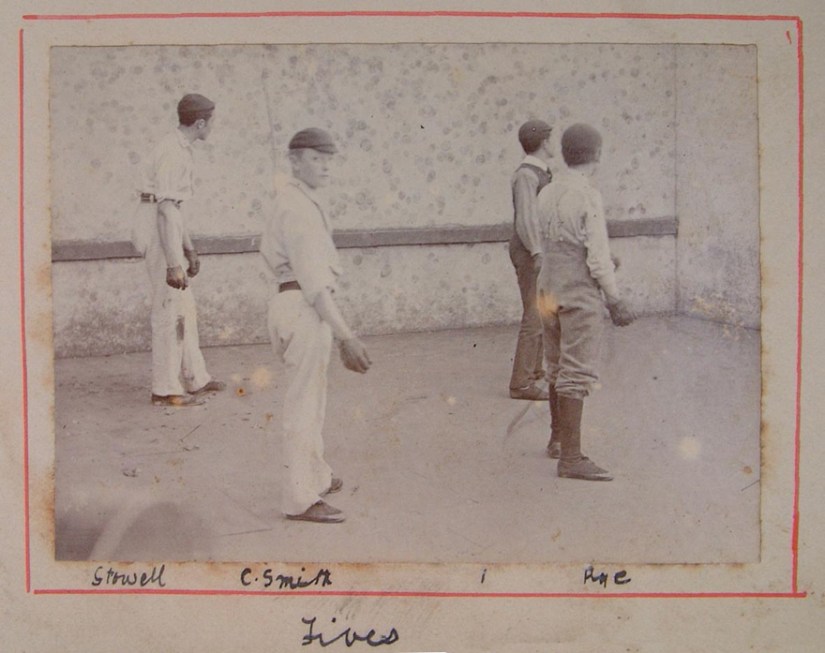

Likewise, you may have heard that he was a handball player, as have I, but details have always been hard to find. The game of handball was much better suited to Lincoln. At 6 feet 4 inches tall, his long legs and gangly arms served the rail splitter well. Muscles honed while wielding an axe as a youth were kept tight and toned as an adult. Lincoln milked his own cows and chopped his own wood even though he was a successful, affluent lawyer with little time to spare. The term handball really didn’t exist in Lincoln’s day. It was called a “game of fives” by Abe and his contemporaries. When Mr. Lincoln went to town, he frequently joined with the boys in playing handball. In the Springfield version, players choose sides to square off against one another. The game is begun by one of the boys bouncing the ball against the wall of the Logan building. As it bounced back, and opponent strikes it in the same manner, so that the ball is kept going back and forth against the wall until someone misses the rebound. ‘Old Abe’ was often the winner, for his long arms and long legs served a good purpose in reaching and returning the ball from any angle his adversary could send it to the wall. The game required two, four or six players, spread equally on each side. The three players who lost paid 10 ¢ each, making 30 ¢ a game. So as you can imagine the games got pretty serious.

The term handball really didn’t exist in Lincoln’s day. It was called a “game of fives” by Abe and his contemporaries. When Mr. Lincoln went to town, he frequently joined with the boys in playing handball. In the Springfield version, players choose sides to square off against one another. The game is begun by one of the boys bouncing the ball against the wall of the Logan building. As it bounced back, and opponent strikes it in the same manner, so that the ball is kept going back and forth against the wall until someone misses the rebound. ‘Old Abe’ was often the winner, for his long arms and long legs served a good purpose in reaching and returning the ball from any angle his adversary could send it to the wall. The game required two, four or six players, spread equally on each side. The three players who lost paid 10 ¢ each, making 30 ¢ a game. So as you can imagine the games got pretty serious. Court clerk Thomas W.S. Kidd spoke of Mr. Lincoln’s love of the game: “In 1859, Zimri A. Enos, Esq., Hon. Chas. A. Keyes, E. L. Baker, Esq., then editor of the Journal, William A. Turney, Esq., Clerk of the Supreme Court, and a number of others, in connection with Mr. Lincoln, had the lot, then an open one, lying between what was known as the United States Court Building, on the northeast corner of the public square, and the building owned by our old friend, Mr. John Carmody, on the alley north of it, on Sixth street, enclosed with a high board fence, leaving a dead wall at either end. In this ‘alley’ could be found Mr. Lincoln, with the gentlemen named and others, as vigorously engaged in the sport as though life depended upon it. He would play until nearly exhausted and then take a seat on the rough board benches arranged along the sides for the accommodation of friends and the tired players.”

Court clerk Thomas W.S. Kidd spoke of Mr. Lincoln’s love of the game: “In 1859, Zimri A. Enos, Esq., Hon. Chas. A. Keyes, E. L. Baker, Esq., then editor of the Journal, William A. Turney, Esq., Clerk of the Supreme Court, and a number of others, in connection with Mr. Lincoln, had the lot, then an open one, lying between what was known as the United States Court Building, on the northeast corner of the public square, and the building owned by our old friend, Mr. John Carmody, on the alley north of it, on Sixth street, enclosed with a high board fence, leaving a dead wall at either end. In this ‘alley’ could be found Mr. Lincoln, with the gentlemen named and others, as vigorously engaged in the sport as though life depended upon it. He would play until nearly exhausted and then take a seat on the rough board benches arranged along the sides for the accommodation of friends and the tired players.” Lincoln’s friend, Dr. Preston H Bailhache, recalled a handball game played on a court built by Patrick Stanley in an ‘alley’ in the rear of his grocery in the Second Ward, which is still standing. “I have sat and laughed many happy hours away watching a game of ball between Lincoln on one side and Hon. Chas. A. Keyes on the other. Mr. Keyes is quite a short man, but muscular, wiry and active as a cat, while his now more distinguished antagonist, as all now know, was tall and a little awkward, but which with much practice and skill in the movement of the ball, together with his good judgment, gave him the greatest advantage. In a very hotly contested game, when both sides were ‘up a stump’ – a term used by the players to indicate an even game – and while the contestants were vigorously watching every movement, Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Turney collided with such force that it came very near preventing his nomination to the Presidency, and giving to Springfield a sensation by his death and burial. Both were badly hurt, but not so badly as to discourage either from being found in the ‘alley’ the next day.”

Lincoln’s friend, Dr. Preston H Bailhache, recalled a handball game played on a court built by Patrick Stanley in an ‘alley’ in the rear of his grocery in the Second Ward, which is still standing. “I have sat and laughed many happy hours away watching a game of ball between Lincoln on one side and Hon. Chas. A. Keyes on the other. Mr. Keyes is quite a short man, but muscular, wiry and active as a cat, while his now more distinguished antagonist, as all now know, was tall and a little awkward, but which with much practice and skill in the movement of the ball, together with his good judgment, gave him the greatest advantage. In a very hotly contested game, when both sides were ‘up a stump’ – a term used by the players to indicate an even game – and while the contestants were vigorously watching every movement, Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Turney collided with such force that it came very near preventing his nomination to the Presidency, and giving to Springfield a sensation by his death and burial. Both were badly hurt, but not so badly as to discourage either from being found in the ‘alley’ the next day.” Another eyewitness was the unofficial gatekeeper of the Handball Court, William Donnelly, a nephew of John Carmody. Years later, Donnelly offered this account to a reporter, “I worked in the Carmody store and usually had charge of the ball court. I smoothed the wall and leveled the ground. I made the balls. Old stockings were rolled out and wound into balls and covered with buckskin. Mr. Lincoln was not a good player. He learned the game when he was too old. But he liked to play and did tolerably well. I remember when he was nominated as though it were yesterday. It was the last day of the convention and he was plainly nervous and restless.”

Another eyewitness was the unofficial gatekeeper of the Handball Court, William Donnelly, a nephew of John Carmody. Years later, Donnelly offered this account to a reporter, “I worked in the Carmody store and usually had charge of the ball court. I smoothed the wall and leveled the ground. I made the balls. Old stockings were rolled out and wound into balls and covered with buckskin. Mr. Lincoln was not a good player. He learned the game when he was too old. But he liked to play and did tolerably well. I remember when he was nominated as though it were yesterday. It was the last day of the convention and he was plainly nervous and restless.” John Carmody recalled another handball game: “An incident took place, during one of those games, which I have retained clearly in my memory. I had a nephew named Patrick Johnson who was very expert in the game. He struck the ball in such a manner that it hit Mr. Lincoln in the ear. I ran to sympathize with him and asked if he was hurt. He said he was not, and as he said it he reached both of his hands toward the sky. Straining my neck to look up into his face, for he was several inches taller than I was, I said to him, ‘Lincoln, if you are going to heaven, take us both.’”

John Carmody recalled another handball game: “An incident took place, during one of those games, which I have retained clearly in my memory. I had a nephew named Patrick Johnson who was very expert in the game. He struck the ball in such a manner that it hit Mr. Lincoln in the ear. I ran to sympathize with him and asked if he was hurt. He said he was not, and as he said it he reached both of his hands toward the sky. Straining my neck to look up into his face, for he was several inches taller than I was, I said to him, ‘Lincoln, if you are going to heaven, take us both.’” In October of 2004, the Smithsonian Institution displayed Abraham Lincoln’s handball as part of their exhibit “Sports: Breaking Records, Breaking Barriers.” It’s small (about the size of a tennis ball), dirty and well worn and really, really old. The ball has “No. 2” stamped on the side but it is unclear if the stamp was on the ball when Lincoln handled it or if it was stamped on the side for reference years later. It came from the Lincoln Home in Springfield, where Lincoln lived with his family from 1844 until 1861.

In October of 2004, the Smithsonian Institution displayed Abraham Lincoln’s handball as part of their exhibit “Sports: Breaking Records, Breaking Barriers.” It’s small (about the size of a tennis ball), dirty and well worn and really, really old. The ball has “No. 2” stamped on the side but it is unclear if the stamp was on the ball when Lincoln handled it or if it was stamped on the side for reference years later. It came from the Lincoln Home in Springfield, where Lincoln lived with his family from 1844 until 1861. Although Assassin John Wilkes Booth was not in the production, he would appear at the McVicker’s 4 times in different productions between 1862 & 1863 while Mr. Lincoln was in the White House. Ironically, the McVickers Theatre was the very first place where actor Harry Hawk began theater work as a call boy, or stagehand. Hawk was the actor on stage alone at the moment of Lincoln’s assassination and likely uttered the last words Mr. Lincoln ever heard. Who knew a well worn piece of leather sports equipment could have so many connections?

Although Assassin John Wilkes Booth was not in the production, he would appear at the McVicker’s 4 times in different productions between 1862 & 1863 while Mr. Lincoln was in the White House. Ironically, the McVickers Theatre was the very first place where actor Harry Hawk began theater work as a call boy, or stagehand. Hawk was the actor on stage alone at the moment of Lincoln’s assassination and likely uttered the last words Mr. Lincoln ever heard. Who knew a well worn piece of leather sports equipment could have so many connections?

Long story short, I won the item. Needless to say, I was excited. Hours turned into days and days turned into weeks as I waited for the General’s lock of hair to arrive. It came via the United States postal service and I could hardly wait to get my first peek at it. Turns out, the item was far more attractive than I expected (for a lock of dead guy’s hair that is). The thick lock of reddish grey hair is about 1.5 inches in length and looks to contain somewhere between 25 and 50 strands of hair. The blue wax seal features an “S” initial that was undoubtedly applied by Forest H. Sweet himself. I could hardly wait to reveal the relic to my children. Sadly, the unveiling was less than I expected. “That’s nice daddy” was the general consensus. It was like buying a kid a Christmas present only to find that they are more interested in playing with the shipping box.

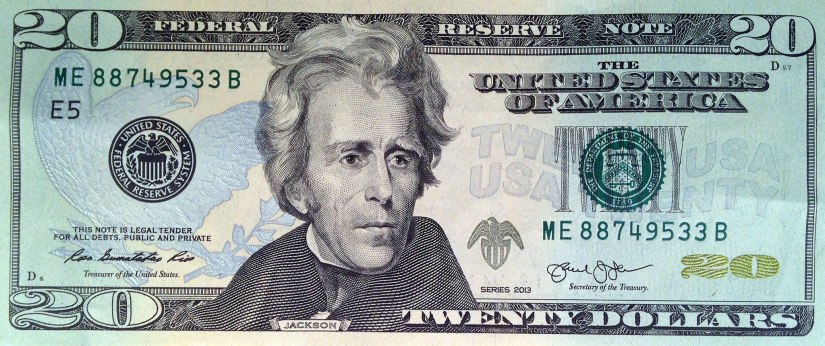

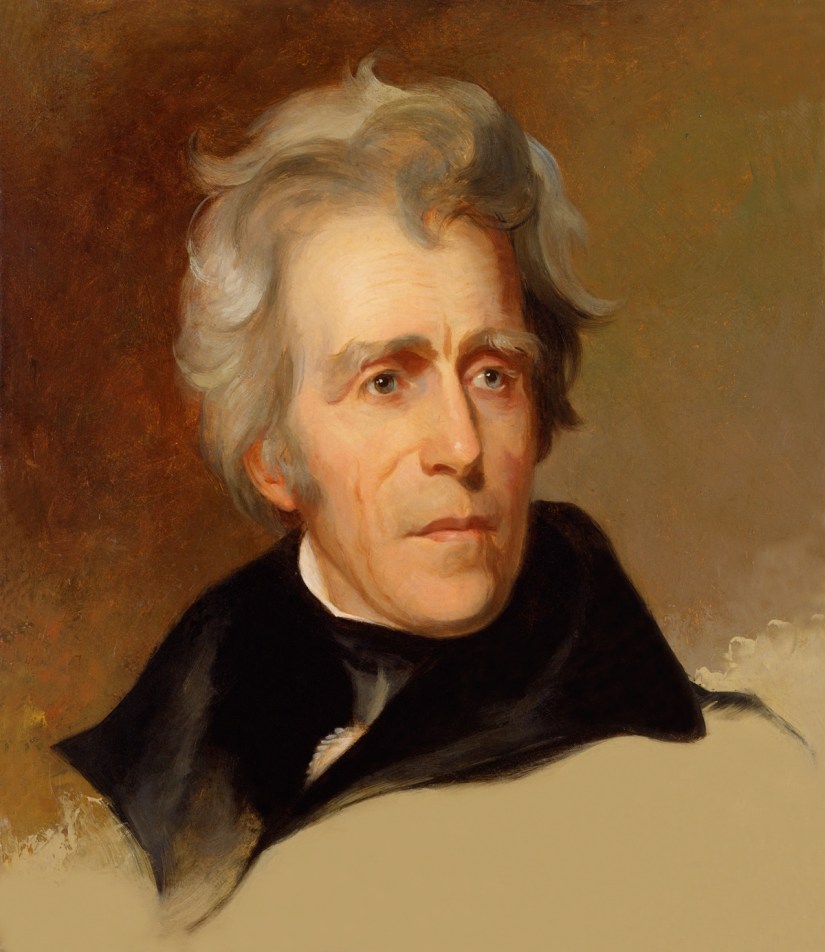

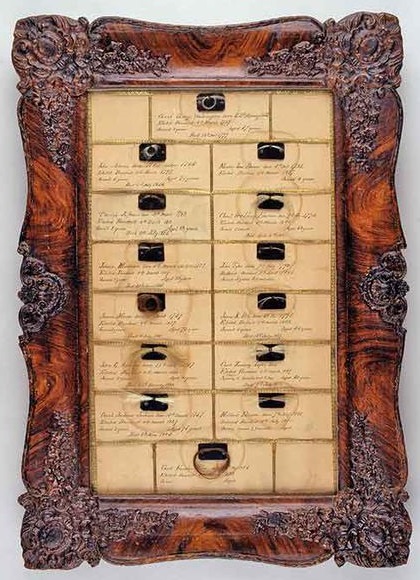

Long story short, I won the item. Needless to say, I was excited. Hours turned into days and days turned into weeks as I waited for the General’s lock of hair to arrive. It came via the United States postal service and I could hardly wait to get my first peek at it. Turns out, the item was far more attractive than I expected (for a lock of dead guy’s hair that is). The thick lock of reddish grey hair is about 1.5 inches in length and looks to contain somewhere between 25 and 50 strands of hair. The blue wax seal features an “S” initial that was undoubtedly applied by Forest H. Sweet himself. I could hardly wait to reveal the relic to my children. Sadly, the unveiling was less than I expected. “That’s nice daddy” was the general consensus. It was like buying a kid a Christmas present only to find that they are more interested in playing with the shipping box. I simply could not resist researching (my wife might say obsessing over) my cherished new relic. Much to my surprise, while searching the net I actually found a website and active blog devoted to “That Glorious Mane“. The website, called “American Lion”, is associated to Andrew Jackson’s hair in name only. But it does touch on the macabre hobby and, more importantly, vindicates my strange purchase by discussing famous locks of hair that have sold recently at auction. In December of 2011, 12 strands of Michael Jackson’s hair, reportedly fished out of a shower drain at New York’s Carlyle Hotel after Jackson stayed there for a charity event during the 1980s, sold at auction in London for around $1,900 to an online gaming casino. The casino plans to use the hair in the construction of a special roulette ball (I don‘t understand it either).

I simply could not resist researching (my wife might say obsessing over) my cherished new relic. Much to my surprise, while searching the net I actually found a website and active blog devoted to “That Glorious Mane“. The website, called “American Lion”, is associated to Andrew Jackson’s hair in name only. But it does touch on the macabre hobby and, more importantly, vindicates my strange purchase by discussing famous locks of hair that have sold recently at auction. In December of 2011, 12 strands of Michael Jackson’s hair, reportedly fished out of a shower drain at New York’s Carlyle Hotel after Jackson stayed there for a charity event during the 1980s, sold at auction in London for around $1,900 to an online gaming casino. The casino plans to use the hair in the construction of a special roulette ball (I don‘t understand it either).

In addition, Jackson suffered from dysentery and malaria contracted during his military campaigns. He was known to have an addiction to coffee, enjoyed a drink or two on occasion, and incessantly chewed tobacco to the extent that brass spittoons were everywhere in the White House. Despite Doctor’s orders, Jackson refused to give up these three vices, regardless of the fact that they gave him migraines. The afore mentioned bullets undoubtedly caused the General to suffer from lead poisoning, quite literally. Luckily, 19 years after that 1832 duel, the bullet causing the most damage was extracted in the White House without anesthesia. Afterwards, Jackson’s health improved tremendously .

In addition, Jackson suffered from dysentery and malaria contracted during his military campaigns. He was known to have an addiction to coffee, enjoyed a drink or two on occasion, and incessantly chewed tobacco to the extent that brass spittoons were everywhere in the White House. Despite Doctor’s orders, Jackson refused to give up these three vices, regardless of the fact that they gave him migraines. The afore mentioned bullets undoubtedly caused the General to suffer from lead poisoning, quite literally. Luckily, 19 years after that 1832 duel, the bullet causing the most damage was extracted in the White House without anesthesia. Afterwards, Jackson’s health improved tremendously . For years, Jackson treated his aches and pains by self-medicating with salts of mercury (often used as a diuretic and purgative in the mid 19th century), as well as ingesting sugar of lead (a lead acetate-used as a food sweetener). Historians have long believed that Andrew Jackson slowly died of mercury and lead poisoning from two bullets in his body and those medications he took for intestinal problems. As proof, historians believe that his symptoms, including excessive salivation, rapid tooth loss, colic, diarrhea, hand tremors, irritability, mood swings and paranoia, were consistent with mercury and lead poisoning. One of Jackson’s doctors liked to give the lead laden sugar to both Andrew and his wife Rachel. They not only ingested it, but used it to bathe their skin and eyes. Jackson’s well-documented, unpredictable behavior were textbook signs of mercury poisoning. Historians described these signs as “thundering and haranguing,” “pacing and ranting” and “at one moment in a towering rage, in the next moment laughing about the outburst. “

For years, Jackson treated his aches and pains by self-medicating with salts of mercury (often used as a diuretic and purgative in the mid 19th century), as well as ingesting sugar of lead (a lead acetate-used as a food sweetener). Historians have long believed that Andrew Jackson slowly died of mercury and lead poisoning from two bullets in his body and those medications he took for intestinal problems. As proof, historians believe that his symptoms, including excessive salivation, rapid tooth loss, colic, diarrhea, hand tremors, irritability, mood swings and paranoia, were consistent with mercury and lead poisoning. One of Jackson’s doctors liked to give the lead laden sugar to both Andrew and his wife Rachel. They not only ingested it, but used it to bathe their skin and eyes. Jackson’s well-documented, unpredictable behavior were textbook signs of mercury poisoning. Historians described these signs as “thundering and haranguing,” “pacing and ranting” and “at one moment in a towering rage, in the next moment laughing about the outburst. “ The submitted strands were taken nearly a quarter century apart for better comparison to check for elevated levels of the heavy metals. The first sample was from 1815, the year of Jackson’s victory at the Battle of New Orleans, the second was from 1839, toward the end of Jackson’s life. According to the American Medical Association, while the mercury and lead levels found in the hair samples were “significantly elevated” in both samples, they were not toxic, said Dr. Ludwag M. Deppisch, a pathologist with Northeastern Ohio University College of Medicine and Forum Health. Officially, Andrew Jackson died at The Hermitage on June 8, 1845, at the age of 78, of chronic tuberculosis, dropsy, heart disease and kidney failure. In other words, the General died a natural death after leaving an extraordinarily unnatural life.

The submitted strands were taken nearly a quarter century apart for better comparison to check for elevated levels of the heavy metals. The first sample was from 1815, the year of Jackson’s victory at the Battle of New Orleans, the second was from 1839, toward the end of Jackson’s life. According to the American Medical Association, while the mercury and lead levels found in the hair samples were “significantly elevated” in both samples, they were not toxic, said Dr. Ludwag M. Deppisch, a pathologist with Northeastern Ohio University College of Medicine and Forum Health. Officially, Andrew Jackson died at The Hermitage on June 8, 1845, at the age of 78, of chronic tuberculosis, dropsy, heart disease and kidney failure. In other words, the General died a natural death after leaving an extraordinarily unnatural life.