Original publish date January 30, 2025.

https://weeklyview.net/2025/01/30/peewee-the-piccolo-born-in-indianapolis/

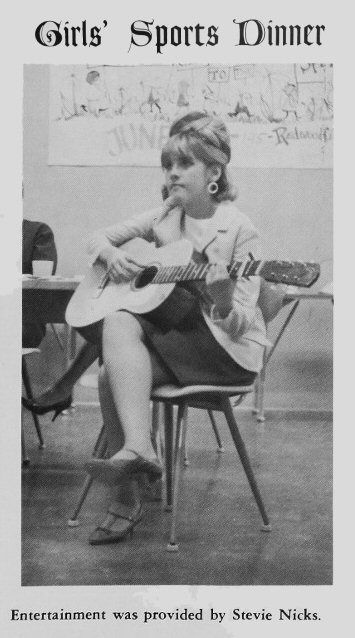

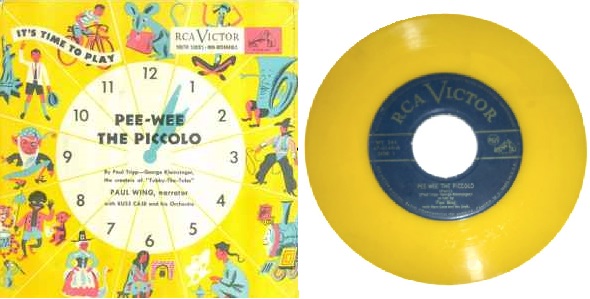

Okay all you Irvington audiophiles, quick, name the first song ever released on a 45 record. If you said it was the “Texarkana Baby” by Eddy Arnold, pat yourself on the back for remembering that lost gem. But you’re wrong. The first commercial 45rpm was “PeeWee the Piccolo” by Russ Case and his Orchestra on RCA Victor records (#47-0146 and b-side #47-0147) released on Feb. 1st, 1949. And it was born right here on the eastside of Indianapolis. Ironically Russ Case (1912-1964), a trumpet player and bandleader, led a few jazz and light music orchestras, including Eddy Arnold’s.

RCA introduced the 45 rpm single to the world on December 7th, 1948 (seven years to the day after the Pearl Harbor attack), at the Sherman Avenue plant in Indianapolis. The confusion among the public comes from the fact that RCA released several commercial 45 singles on March 31st, 1949, including Arnold’s “Texarkana Baby.” The irony is that while “Pee Wee the Piccolo” is largely forgotten, “Texarkana Baby” topped Billboard’s country chart for three weeks, reaching #18 on the Best Selling Popular Retail Records chart. And it was the b-side of the single for Arnold’s standard hit “Bouquet of Roses.”

“Pee-Wee The Piccolo” is a children’s record narrated by Academy Award winner Paul Wing (1892-1957). Wing was captured by the Japanese in the Philippines in 1942, survived the Bataan Death March, and was held prisoner in the World War II prisoner of war camp portrayed in the 2005 film The Great Raid. “Pee-Wee The Piccolo” was written by Paul Tripp and George Kleinsinger, who also created Tubby The Tuba. RCA color-coded their singles, pressing children’s 45-rpm records on yellow vinyl, popular music on black vinyl, country on green vinyl, classical on red vinyl, instrumental music on blue vinyl, and R&B and gospel on orange vinyl, international music was light blue, and musicals midnight blue. Eventually, they would all be pressed in black.

The 45′s tie-in to World War II is not without purpose. The 45 rpm single can trace its earliest origins to that conflict. Like many fields, World War II put a major dent in the music industry. Most homefront record and phonograph makers retooled their factories for the manufacture of products for the war effort. A wartime blockade stopped the import of shellac, the material from which .78 records were made. With that supply cut off, manufacturers scrambled for a new material to make records. The industry had been experimenting with synthetic PVC (polyvinyl chloride) since the 1930s, but it was more expensive to produce than shellac. CBS (Columbia Broadcasting System) engineers realized that PVC’s material properties meant that a vinyl record could be made thinner and stronger than a shellac record and that the grooves could be cut thinner, allowing more music to fit on each side. More music meant more money, outweighing the cost of the more expensive material. So the 33 rpm format was born.

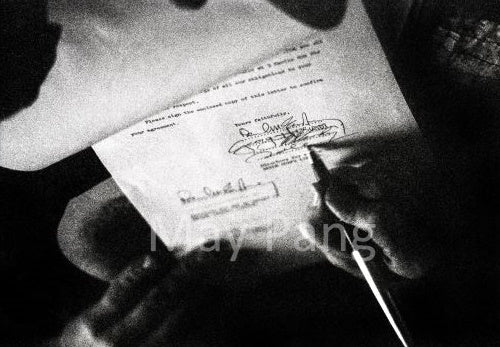

Around September of ’48, William Paley at CBS offered RCA’s David Sarnoff the rights to the 33 technology at no cost. Paley thought that sharing his secret with his chief competitor would help boost the 33 format record sales for both companies. Sarnoff adroitly thanked Paley and told him he would think about it. Paley hadn’t realized that RCA had already perfected it’s secret 45 project. Paley was shocked and CBS miffed when RCA rolled out the 45 a few months later. The 45 rpm record became RCA’s answer to Columbia’s 33 1/3 rpm long-playing disc. The two systems directly competed with each other to replace 78 rpm records, bewildering consumers, and causing a drop in record sales. In media the period from ’49 to ’51 was referred to as “the war of the speeds” years.

A myth persists that the single’s designation of “45″ came from subtracting Columbia’s new 33 rpm format speed from the old 78: equaling 45. According to “Vinyl: A History of the Analogue Record” by Richard Osborne, “the speed was based upon calculations made by the best balance between playing time and signal-to-noise ratio given by a groove density of 3 minutes per radial inch, and also that the innermost groove of a disc should be half the diameter of the outermost groove. Given the 6 7/8 diameter of the record it was found that 45 rpm provided the desired playing time within the designated bandwidth.” No wonder the 78 minus 33 urban legend remains so persistent — it’s easier to remember.

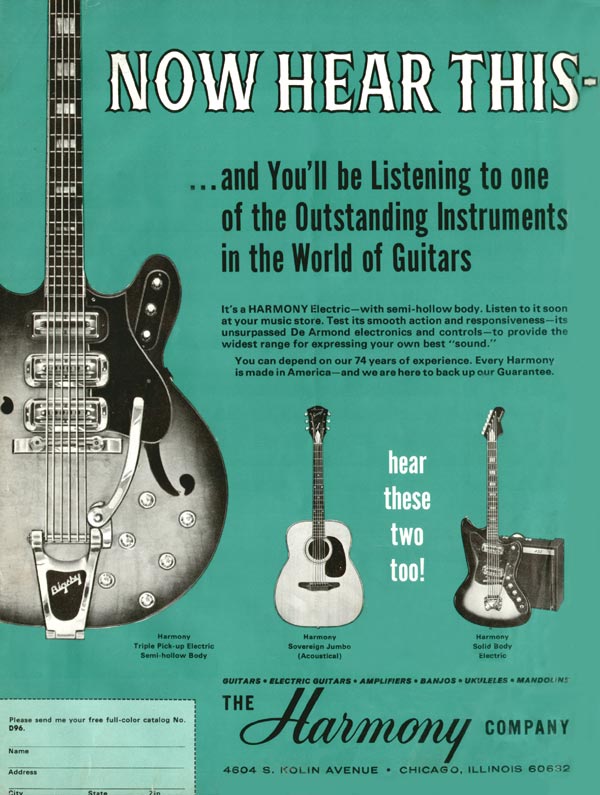

Engineers from both companies had been working on a replacement for the 78 since before the war, experimenting with speeds ranging from 30 to 50 RPM. They were balancing the playing time (5 minutes – the same as a 12″ 78) with disk diameter, to get the most compact format that would have a surface velocity and lack of “pinch effect” so that the sound would not degrade as the stylus reached the inner diameter. In fact, for all but the outer inch or so, the 45 has a higher surface velocity than a 12″ LP. Both Edison and Victor had tried to introduce long-playing records in the 1920s and failed. In 1949 Capitol and Decca started issuing the new LP format, and RCA relented and issued its first LP in January 1950. While the LP could comfortably hold a large selection of music on each side, the 45, with its large central hole, worked better on automatic changers (like jukeboxes).

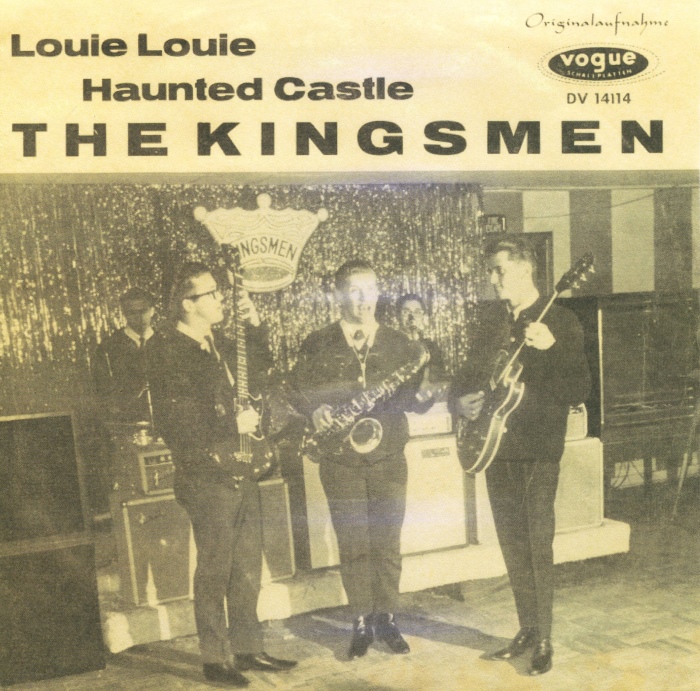

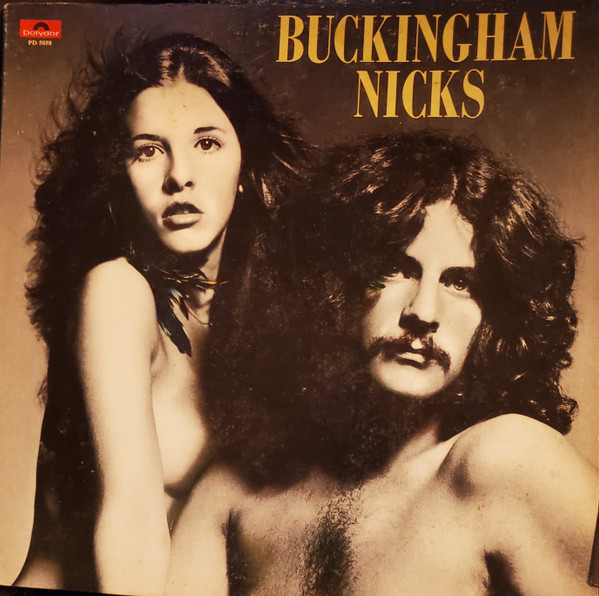

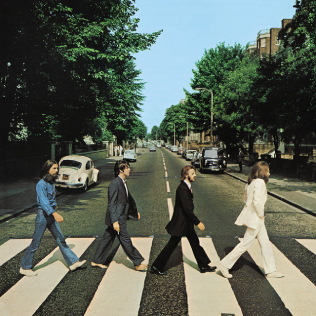

However the 45 rpm was gaining in popularity, and Columbia issued its first 45s in February 1951. Soon, other record companies saw the mass consumer appeal the new format allowed. By 1954 more than 200 million 45s had been sold. According to the New York Times, the peak year for the seven-inch single was 1974, when 250 million were sold. In the end, the war of the speeds ended without a decisive winner. By the early Eighties, the 45 began dying a slow, humiliating death. The number of jukeboxes in the country declined, stadium rock fans increasingly gravitated toward albums, and the cassette format (and even the wasteful “cassette single” and “mini-CD” format) began overtaking vinyl 45s.

Like most people my age, I fell in love with 45s in the early 1970s. Mostly because they fit into my limited allowance budget as a kid. That was, until about 1975 when the companies all raised the price of a 45 from $0.99 to $1.49! Then I had to be choosy. In most cases, the best song from an album would make it onto the 45 and, if I was lucky, there could be a b-side that was an unexpected bonus, sometimes a song not even on the album. Bingo, bonus track! Many of those 45s were made right here in Indianapolis. What’s more, back in the late 1960s/early 1970s it seemed like everyone in my family worked at that RCA plant on Sherman Ave. I remember that Mom and Dad got to pick out 2 or 3 free records every quarter, so I had a leg up on the competition (my sisters).

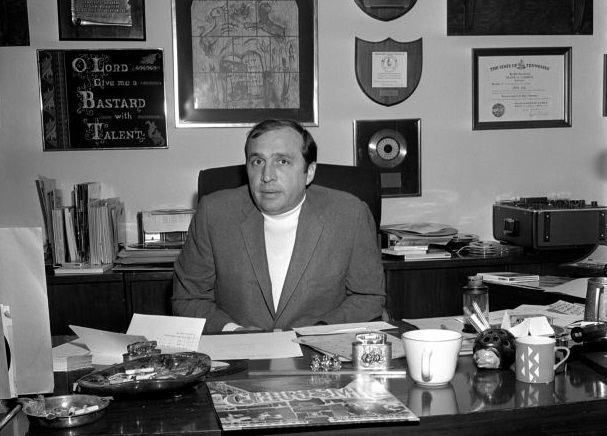

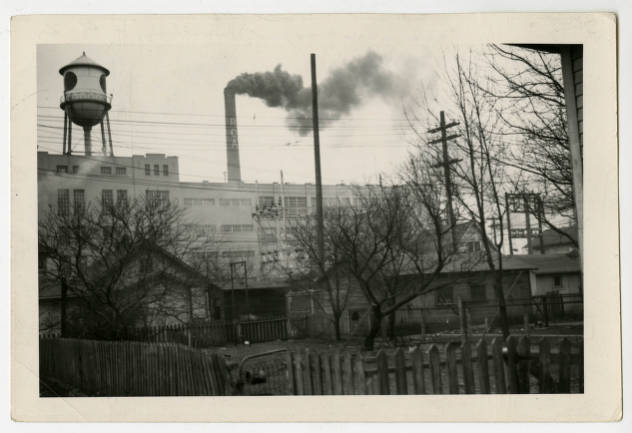

Built in the 1920s, the RCA plant on the near eastside was a massive site that, during its heyday in the 1950s, employed over 8,000 people. RCA featured over 20 buildings on its 50-acre site, and aside from making records, the plant produced electronics like televisions, stereos, and radios. A gradual decline in business began in the 1970s, eventually leading to RCA being sold to GE in 1986. The Sherman Ave. plant operated for a few more years before closing in 1995. A heavy machinery and storage company operated in a small portion of the plant and a recycling nonprofit operated in the main building along Michigan St. for years before leaving in 2012. The RCA Sherman Plant was ultimately demolished in late January/early February 2017.

Elvis Presley and Dolly Parton were two of the bigger names that toured the plant, although many bands and artists made the trip to the RCA plant to see how their records were made. One of the more famous records made there was Elvis Presley’s “Moody Blue” record, a special presentation copy of which was given to Elvis during his final concert at Market Square Arena on June 26, 1977. As it happens, the stage where Elvis stood when he received that gold record now rests inside the Irving Theatre.

Dad, who was trained as a draftsman in the service, worked in the relatively new computer processing area at the Sherman Ave. facility. He would take a sweater or zipper-pull fleece with him every day regardless of the season because back then the computers ran pretty hot and the room was kept so cold. They let employees smoke back in those days in the computer room and Dad smoked a pipe. I remember he worked with IBM cards back then. Those punchcards sorted all the info for the RCA record club members, which numbered in the hundreds of thousands.

My father lived for many years across the street from the plant on Sherman Avenue. He relished the idea of walking to and from work and eating lunches at home. The plant was an awesome sight to see when it was still standing. After it was vacated in the early 2000s, it became the largest abandoned place in Indy (besides the coke plant). There were some reminders of its former life throughout the building (the RCA dog could still be found in the main building) and leftover remnants from the other companies that operated there.

During those derelict years, I may (or may not) have surreptitiously ventured into the empty building. It was pretty sketch back then and you were likely to run into other people, mostly vagrants, scrappers, and other neighborhood kids. The attics had catwalks from which one could access various rooms/areas throughout the building via small doors. I remember one door in the back of the men’s room. There were muddy raccoon footprints all over the bathroom tile floors: proof that the critters would come in at night to drink out of the toilets. Some rooms were lined with meshed steel Faraday cages. The level beneath the main offices had large mounds of dirt reportedly earmarked for a BMX track that never materialized. When Thomson Consumer Electronics moved north to their new sparkling aqua green and blue paneled building at I-465 and Meridian, RCA left a ton of office furniture and obsolete audio-visual equipment behind in the building.

My dad worked in that building for over three decades. He died in 1997 just months away from retirement. My grandparents and my mother worked there in the 1960s. And it was in that lobby where I saw my stepmother Bonnie for the last time in 1997 before she left for Tennessee never to return. Back then RCA had a notary public in residence just inside the door. Tens of thousands of Hoosiers worked at that plant during its 75-year lifespan. Now, the vacant space is just a large patch of overgrown weeds and wild grass. My dad’s house sits empty, the doors and windows boarded up. Life goes on, the world still turns, and soon anyone with memories of working in that plant will fade away as well. Like phone booths, inspection stations, long-distance operators, and most of the products made in that building, RCA is just a distant memory now.