Original publish date: June 20, 2011 Reissue: April 30, 2020

To many Hoosiers, summertime conjures up images of cozy family car trips spent searching for the odd and unusual sites that allow us all to forget about life for awhile while providing memories that will last forever. Don’t let today’s high gas prices keep you from enjoying that summer road trip. The average price for a gallon of gas hovers around $3.80—that’s lower than a month ago, but about a dollar more than last year at this time. Yes, gas expenditures can add up quickly, but don’t let that deter you from jumping in the car and driving all over our fair state.

Most of you know that I have a particular affinity for the Historic National Road. My love for the Road is rooted in the roadside Americana sights I remember from my childhood cleverly designed to draw my eyes towards them like a beacon on the horizon. I suspect that many of you can easily remember those larger than life roadside attractions that used to dot our cityscape like Mr. Bendo, the giant muffler man and the TeePee restaurants. Most of these old landmark roadside attractions have been torn down or rotted away, but a precious few still stand as a testament to a simpler era.

These unique roadside attractions began popping up along our highways in the 1930s and flourished into the 1960s. But the 1950s were their heyday. The Ike Era fifties was the decade of car culture; gas was cheap and families took to the open road, many for the very first time. The US interstate highway system was authorized in 1956 and construction began almost immediately in many states. Until then, families relied on connecting state road systems that took them on meandering journeys through big cities and small towns alike.

These unique roadside attractions began popping up along our highways in the 1930s and flourished into the 1960s. But the 1950s were their heyday. The Ike Era fifties was the decade of car culture; gas was cheap and families took to the open road, many for the very first time. The US interstate highway system was authorized in 1956 and construction began almost immediately in many states. Until then, families relied on connecting state road systems that took them on meandering journeys through big cities and small towns alike.

Beginning in the 1940s, roadside attractions started to spring up around the country in an effort to lure visitors to stop based on the exterior appearance alone. In the days before air conditioning and drive-through restaurants, the promise of free ice water and clean restrooms was a sufficient lure. However, in an effort to make themselves standout from the ever-crowded landscape, some roadside attractions began to feature exotic animals, games, quirky shopping or just really big things–such as the world’s largest advertising mascot signs.

Although modern construction has ensured that you are never far from fast food and gas, if you drive highway 40 today, it is easy to imagine how that drive must have felt back in the day. Today, driving along many of Indiana’s classic highways (Michigan Road, Brookville Road, Washington Street, Lincoln Highway) traces of old gift shops, restaurants, amusement parks and motels dot the landscape. Many of you can easily recall the giant TeePees that crowned the roof of the aptly named “TeePee” restaurants on the grounds of the state fairgrounds and on the cities southside. For me, I’ll always remember the giant coffee pot that formed the roof of the “Coffee Pot” restaurant in Pennville near Richmond on the National Road.

Although modern construction has ensured that you are never far from fast food and gas, if you drive highway 40 today, it is easy to imagine how that drive must have felt back in the day. Today, driving along many of Indiana’s classic highways (Michigan Road, Brookville Road, Washington Street, Lincoln Highway) traces of old gift shops, restaurants, amusement parks and motels dot the landscape. Many of you can easily recall the giant TeePees that crowned the roof of the aptly named “TeePee” restaurants on the grounds of the state fairgrounds and on the cities southside. For me, I’ll always remember the giant coffee pot that formed the roof of the “Coffee Pot” restaurant in Pennville near Richmond on the National Road.

But, who remembers the “Mr. Bendo”, the muffler man? These giant statues routinely stood outside auto shops, usually with one arm outstretched while towering over the road with a muffler resting in his curved hand. Spotted in various incarnations all over the United States, these advertising icons were extraordinarily popular throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Legend claims that all of the original Muffler Men came from a single mold owned by Prewitt Fiberglass (later International Fiberglass). The first Muffler Man was allegedly a giant Paul Bunyan developed for a café on Route 66 in Arizona. Later incarnations were Native Americans, cowboys, spacemen and even the Uniroyal girl, who appeared in both a dress and a bikini. These behemoths either elicited fear or joy, but never failed to spur the imagination. Locally, you can find one of these “Mr. Bendo” statues at 1250 W. 16th St.

But, who remembers the “Mr. Bendo”, the muffler man? These giant statues routinely stood outside auto shops, usually with one arm outstretched while towering over the road with a muffler resting in his curved hand. Spotted in various incarnations all over the United States, these advertising icons were extraordinarily popular throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Legend claims that all of the original Muffler Men came from a single mold owned by Prewitt Fiberglass (later International Fiberglass). The first Muffler Man was allegedly a giant Paul Bunyan developed for a café on Route 66 in Arizona. Later incarnations were Native Americans, cowboys, spacemen and even the Uniroyal girl, who appeared in both a dress and a bikini. These behemoths either elicited fear or joy, but never failed to spur the imagination. Locally, you can find one of these “Mr. Bendo” statues at 1250 W. 16th St.

Today, you can get in the car and drive around Indianapolis in search of these classic old statues along with other oversized oddity signs. There are many websites and clubs devoted solely to cataloging and photographing these roadside oddities for posterity. Most of these Hoosier relics are outside of the city limits proper, but they can be found easily on a one-tank-trip. By the way, most importantly, bring your camera. Here is a partial list of these roadside oddities to give you a place to start.

Closeby, there is a giant Uncle Sam and his two smaller nephews on Shadeland Ave (between Washington St and 10th). There are two giant globes, one on Michigan Road on the way to Zionsville and the other near the pyramids visible from the interstate. There is a large dairy cow on South Shortridge Rd (between Washington St and Brookville Rd) sitting behind a 10-foot chain link fence topped with barbed wire and guard at the gate. There are two large swans in the middle of ponds, one on Mitthoffer (Between 21st St and 30th St) and the other on Pendleton Pike. Incidently there is a big fiberglass cow at 9623 Pendleton Pike near the afore mentioned swan.

Closeby, there is a giant Uncle Sam and his two smaller nephews on Shadeland Ave (between Washington St and 10th). There are two giant globes, one on Michigan Road on the way to Zionsville and the other near the pyramids visible from the interstate. There is a large dairy cow on South Shortridge Rd (between Washington St and Brookville Rd) sitting behind a 10-foot chain link fence topped with barbed wire and guard at the gate. There are two large swans in the middle of ponds, one on Mitthoffer (Between 21st St and 30th St) and the other on Pendleton Pike. Incidently there is a big fiberglass cow at 9623 Pendleton Pike near the afore mentioned swan.

The old Galyan’s bear statue sits on the edge of the Eagle Creek Reservoir. When Dick’s Sporting Goods purchased Galyan’s, the company donated the statue to the City of Indianapolis. There are two huge bowling pins, one at Woodland bowl on the northside and the other at Expo bowl on the southside (visible from I-465). Don’t forget about the giant dinosaurs hatching from eggs at the Children’s Museum on the corner of 30th and N. Meridian Streets near downtown.

The old Galyan’s bear statue sits on the edge of the Eagle Creek Reservoir. When Dick’s Sporting Goods purchased Galyan’s, the company donated the statue to the City of Indianapolis. There are two huge bowling pins, one at Woodland bowl on the northside and the other at Expo bowl on the southside (visible from I-465). Don’t forget about the giant dinosaurs hatching from eggs at the Children’s Museum on the corner of 30th and N. Meridian Streets near downtown.

If you’re feeling adventurous, there is the world’s largest toilet in downtown Columbus, part of a giant house display. Once you make it up to the top floor of the “house”, you can jump in the toilet and slide down to the bottom. Near Centerville, there is a giant candle visible from I-70. In Fortville on the Mass Avenue extension (Highway 67) there is a giant pink elephant wearing eyeglasses and drinking a martini. In Franklin, a furniture store at 4108 S. US Hwy 31 has a towering chest of drawers and what they claim to be the world’s largest rocking chair.

If you’re traveling to Logansport, you can visit three giant statues in the same town; Mr. Happy Burger on the corner of US Hwy 24/W. Market St. and W. Broadway St. features a fiberglass black bull wearing a chef’s hat and a bib as does the Mr. Happy Burger located at 3131 E. Market St. along with a giant chicken statue at 7118 W. US Hwy 24 (on the north side) that you can see from the road. Muncie has two giants; A big fiberglass muffler man stands alongside the scissor-lifts & heavy equipment in the Mac Allister rental lot at 3500 N. Lee Pit Rd. and a Paul Bunyan statue is the mascot of a bar named Timbers at 2770 W. Kilgore Ave.

If you’re traveling to Logansport, you can visit three giant statues in the same town; Mr. Happy Burger on the corner of US Hwy 24/W. Market St. and W. Broadway St. features a fiberglass black bull wearing a chef’s hat and a bib as does the Mr. Happy Burger located at 3131 E. Market St. along with a giant chicken statue at 7118 W. US Hwy 24 (on the north side) that you can see from the road. Muncie has two giants; A big fiberglass muffler man stands alongside the scissor-lifts & heavy equipment in the Mac Allister rental lot at 3500 N. Lee Pit Rd. and a Paul Bunyan statue is the mascot of a bar named Timbers at 2770 W. Kilgore Ave.

There is a car-sized basketball shoe at the Steve Alford All-American Inn on State Road 3 in New Castle and you can visit the towering, thickly-clothed “Icehouse man” painted in cool blue colors, the mascot of a bar named Icehouse at 1550 Walnut St. in New Castle. A balloon-shaped man with a chef’s hat, known by locals as “The Baker Man” is perched atop a pole with his arm raised in a friendly wave at 315 S. Railroad St. in Shirley, Indiana. And of course, who can forget the giant Santa Claus that greets visitors to Santa Claus, Indiana.

There is a car-sized basketball shoe at the Steve Alford All-American Inn on State Road 3 in New Castle and you can visit the towering, thickly-clothed “Icehouse man” painted in cool blue colors, the mascot of a bar named Icehouse at 1550 Walnut St. in New Castle. A balloon-shaped man with a chef’s hat, known by locals as “The Baker Man” is perched atop a pole with his arm raised in a friendly wave at 315 S. Railroad St. in Shirley, Indiana. And of course, who can forget the giant Santa Claus that greets visitors to Santa Claus, Indiana.

I’m sure I’m forgetting a few, perhaps many, but if this list helps stir up some old roadside memories among you, or better yet, gets you charged up to take an inexpensive holiday in search of roadside oddities, well, then it was a worthwhile read.

I’m sure I’m forgetting a few, perhaps many, but if this list helps stir up some old roadside memories among you, or better yet, gets you charged up to take an inexpensive holiday in search of roadside oddities, well, then it was a worthwhile read.

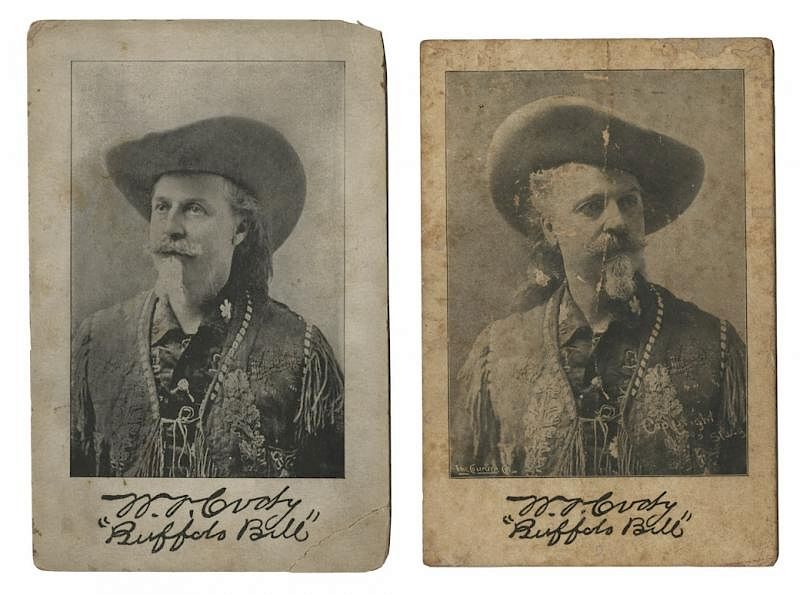

Buffalo Bill Cody was the real deal-he had fought Indians, hunted buffalo, and scouted the Northern Plains for General Phil Sheridan and Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer along America’s vast Western frontier. He was a fur-trapper, gold-miner, bullwhacker, wagon master, stagecoach driver, dude rancher, camping guide, big game hunter, hotel manager, Pony Express rider, Freemason and inventor of the traveling Wild West show. Oh, yeah, and he was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1872 for, unsurprisingly, “Gallantry” during the Indian Wars. His medal, along with medals of 910 other recipients, was revoked in February of 1917 when Congress retroactively tightened the rules for the honor. Luckily, the action came one month after Cody died in 1917. It was reinstated in 1989.

Buffalo Bill Cody was the real deal-he had fought Indians, hunted buffalo, and scouted the Northern Plains for General Phil Sheridan and Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer along America’s vast Western frontier. He was a fur-trapper, gold-miner, bullwhacker, wagon master, stagecoach driver, dude rancher, camping guide, big game hunter, hotel manager, Pony Express rider, Freemason and inventor of the traveling Wild West show. Oh, yeah, and he was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1872 for, unsurprisingly, “Gallantry” during the Indian Wars. His medal, along with medals of 910 other recipients, was revoked in February of 1917 when Congress retroactively tightened the rules for the honor. Luckily, the action came one month after Cody died in 1917. It was reinstated in 1989. But Cody’s biggest achievement came as the wild west frontier he had helped create was vanishing. Buffalo Bill’s “Wild West” shows featured western icons like Wild Bill Hickok, Annie Oakley, Frank Butler, Bill Pickett, Mexican Joe, Adam Bogardus, Buck Taylor, Geronimo, Red Cloud, Chief Joseph, Texas Jack, Pawnee Bill, Tillie Baldwin, Bronco Bill, Coyote Bill, May Lillie, and a “Congress” of cowboys, soldiers, Native American Indians and Mexican vaqueros. Movie stars Will Rogers and Tom Mix and World Heavyweight Champion Jess Willard kicked off their careers as common cow punchers for Buffalo Bill. Cody performed for Kings, Queens, Presidents, Generals, Dignitaries and just plain folk in small towns, at World’s Fairs, stadiums and arenas all over the world.

But Cody’s biggest achievement came as the wild west frontier he had helped create was vanishing. Buffalo Bill’s “Wild West” shows featured western icons like Wild Bill Hickok, Annie Oakley, Frank Butler, Bill Pickett, Mexican Joe, Adam Bogardus, Buck Taylor, Geronimo, Red Cloud, Chief Joseph, Texas Jack, Pawnee Bill, Tillie Baldwin, Bronco Bill, Coyote Bill, May Lillie, and a “Congress” of cowboys, soldiers, Native American Indians and Mexican vaqueros. Movie stars Will Rogers and Tom Mix and World Heavyweight Champion Jess Willard kicked off their careers as common cow punchers for Buffalo Bill. Cody performed for Kings, Queens, Presidents, Generals, Dignitaries and just plain folk in small towns, at World’s Fairs, stadiums and arenas all over the world. During the late 19th century, the troupe included as many as 1,200 performers.The shows consisted of historical scenes punctuated by feats of sharpshooting, military drills, staged races, rodeo events, and sideshows. Real live Native American Indians were portrayed as the “Bad Guys”, most often shown attacking wagon trains with Buffalo Bill or one of his colleagues riding in and saving the day. Other staged scenes included Pony Express riders, stagecoach robberies, buffalo-hunting and a melodramatic re-enactment of Custer’s Last Stand in which Cody himself portrayed General Custer.

During the late 19th century, the troupe included as many as 1,200 performers.The shows consisted of historical scenes punctuated by feats of sharpshooting, military drills, staged races, rodeo events, and sideshows. Real live Native American Indians were portrayed as the “Bad Guys”, most often shown attacking wagon trains with Buffalo Bill or one of his colleagues riding in and saving the day. Other staged scenes included Pony Express riders, stagecoach robberies, buffalo-hunting and a melodramatic re-enactment of Custer’s Last Stand in which Cody himself portrayed General Custer. By the turn of the 20th century, William F. Cody was probably the most famous American in the world. Cody symbolized the West for Americans and Europeans, his shows seen as the entertainment triumphs of the ages. In Indiana, entire towns turned out to see the people and scenes they had read about in the dime novels and newspaper stories they grew up on and continued to read daily. Buffalo Bill’s performances were usually preceded by a downtown parade of stagecoaches, soldiers, acrobats, wild animals, chuckwagons, calliopes, cowboys, Indians, outlaws and trick shooters firing off birdshot at targets thrown haphazardly in the air. In 1898, admission to the show was half-a-buck for adults, two bits for children under 9. The Buffalo Bill show traveled by their own special train, usually arriving early in the morning and giving two shows before packing up to travel all night to the next town.

By the turn of the 20th century, William F. Cody was probably the most famous American in the world. Cody symbolized the West for Americans and Europeans, his shows seen as the entertainment triumphs of the ages. In Indiana, entire towns turned out to see the people and scenes they had read about in the dime novels and newspaper stories they grew up on and continued to read daily. Buffalo Bill’s performances were usually preceded by a downtown parade of stagecoaches, soldiers, acrobats, wild animals, chuckwagons, calliopes, cowboys, Indians, outlaws and trick shooters firing off birdshot at targets thrown haphazardly in the air. In 1898, admission to the show was half-a-buck for adults, two bits for children under 9. The Buffalo Bill show traveled by their own special train, usually arriving early in the morning and giving two shows before packing up to travel all night to the next town. According to the official “Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave in Golden, Colorado” website, from 1873 to 1916 William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody appeared in Indiana 155 times, touring 38 different Hoosier cities. Some of those cities are obvious, some obscure. Anderson (3 times), Auburn, Bedford, Bluffton, Columbus, Crawfordsville (2 times), Elkhart (3 times), Evansville (12 times), Fort Wayne (12 times), Frankfort, Gary (2 times), Goshen (2 times), Huntington, Kendallville, Kokomo (4 times), La Porte, Lafayette (14 times), Lawrenceburg, Logansport (8 times), Madison, Marion (3 times), Michigan City, Muncie (7 times), New Albany (3 times), North Vernon (4 times), Peru, Plymouth, Portland, Richmond (8 times), Shelbyville, South Bend (8 times), Tell City, Terre Haute (17 times), Valparaiso, Vincennes (4 times), Warsaw (2 times), Washington and of course Indianapolis (19 times). Strangely, although Buffalo Bill appeared in the Circle City more than any other during his career, his tour did not stop here for his final tour in 1916. preferring instead to swing thru the far northern section of our state on the way to Chicago.

According to the official “Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave in Golden, Colorado” website, from 1873 to 1916 William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody appeared in Indiana 155 times, touring 38 different Hoosier cities. Some of those cities are obvious, some obscure. Anderson (3 times), Auburn, Bedford, Bluffton, Columbus, Crawfordsville (2 times), Elkhart (3 times), Evansville (12 times), Fort Wayne (12 times), Frankfort, Gary (2 times), Goshen (2 times), Huntington, Kendallville, Kokomo (4 times), La Porte, Lafayette (14 times), Lawrenceburg, Logansport (8 times), Madison, Marion (3 times), Michigan City, Muncie (7 times), New Albany (3 times), North Vernon (4 times), Peru, Plymouth, Portland, Richmond (8 times), Shelbyville, South Bend (8 times), Tell City, Terre Haute (17 times), Valparaiso, Vincennes (4 times), Warsaw (2 times), Washington and of course Indianapolis (19 times). Strangely, although Buffalo Bill appeared in the Circle City more than any other during his career, his tour did not stop here for his final tour in 1916. preferring instead to swing thru the far northern section of our state on the way to Chicago. Buffalo Bill traveled with five different shows during his lifetime: 1872 – 1886: Buffalo Bill’s Combination acting troop / 1884 – 1908: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West / 1909 – 1913: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Pawnee Bill’s Far East / 1914 – 1915: Sells-Floto Circus and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West / 1916: Buffalo Bill and the 101 Ranch Combined. By the end, Buffalo Bill had to be strapped onto his saddle to keep from falling off (after all, he was over 70-years old at the time). Despite the perceived exploitation of his Wild West Shows, Cody respected Native Americans, was among the earliest supporters of women’s rights and was a pioneer in the conservation movement and an early advocate for civil rights. He described Native Americans as “the former foe, present friend, the American” and once said that “every Indian outbreak that I have ever known has resulted from broken promises and broken treaties by the government.” He also said, “What we want to do is give women even more liberty than they have. Let them do any kind of work they see fit, and if they do it as well as men, give them the same pay.”

Buffalo Bill traveled with five different shows during his lifetime: 1872 – 1886: Buffalo Bill’s Combination acting troop / 1884 – 1908: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West / 1909 – 1913: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Pawnee Bill’s Far East / 1914 – 1915: Sells-Floto Circus and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West / 1916: Buffalo Bill and the 101 Ranch Combined. By the end, Buffalo Bill had to be strapped onto his saddle to keep from falling off (after all, he was over 70-years old at the time). Despite the perceived exploitation of his Wild West Shows, Cody respected Native Americans, was among the earliest supporters of women’s rights and was a pioneer in the conservation movement and an early advocate for civil rights. He described Native Americans as “the former foe, present friend, the American” and once said that “every Indian outbreak that I have ever known has resulted from broken promises and broken treaties by the government.” He also said, “What we want to do is give women even more liberty than they have. Let them do any kind of work they see fit, and if they do it as well as men, give them the same pay.” Although many reports make it seem that Buffalo Bill died a pauper, at the time of his death on January 10, 1917, Cody’s fortune had “dwindled” to less than $100,000 (approximately $2 million today). So you see, there is more to Buffalo Bill Cody than meets the eye. Although often portrayed in pantomime as a grossly exaggerated caricature of a buckskin clad circus act, he really was the real deal.

Although many reports make it seem that Buffalo Bill died a pauper, at the time of his death on January 10, 1917, Cody’s fortune had “dwindled” to less than $100,000 (approximately $2 million today). So you see, there is more to Buffalo Bill Cody than meets the eye. Although often portrayed in pantomime as a grossly exaggerated caricature of a buckskin clad circus act, he really was the real deal.

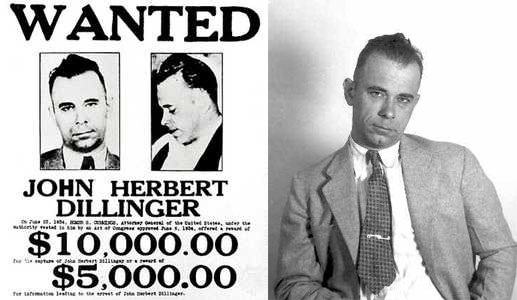

Located at 815 Massachusetts Avenue near the headquarters of the Indiana State Police, Dillinger and Vinson brazenly strolled into the bank with guns drawn. Assistant manager Lloyd Rinehart, seated at his desk chatting casually on the telephone, heard someone yell: “This is a stickup! We mean business.” He later told police that he thought it was a joke and didn’t even look up to interrupt his conversation. “Get off that damned telephone,” Dillinger snarled. Rinehart looked up from his desk to find he was staring into the barrel of a .45 automatic.

Located at 815 Massachusetts Avenue near the headquarters of the Indiana State Police, Dillinger and Vinson brazenly strolled into the bank with guns drawn. Assistant manager Lloyd Rinehart, seated at his desk chatting casually on the telephone, heard someone yell: “This is a stickup! We mean business.” He later told police that he thought it was a joke and didn’t even look up to interrupt his conversation. “Get off that damned telephone,” Dillinger snarled. Rinehart looked up from his desk to find he was staring into the barrel of a .45 automatic. While nervously adjusting his handkerchief-mask and waving his pistol in the air, Vinson pestered Dillinger to “Hurry Up, Hurry Up.” Dillinger casually emptied all of the cash drawers and made his way to the vault. There he discovered a cache of 1,000 half dollars which he gleefully threw over the top of the teller cage bars to Vinson as the Hoosier bandit giggled like a schoolboy. Unbeknownst to them, the bandits had stumbled upon the payroll of the “Real Silk Hosiery Company”, which was the nation’s largest shipper of c.o.d. parcel post packages whose headquarters were located in the Lockerbie Square area. (The building has since been converted to stylish apartments and condominiums.)

While nervously adjusting his handkerchief-mask and waving his pistol in the air, Vinson pestered Dillinger to “Hurry Up, Hurry Up.” Dillinger casually emptied all of the cash drawers and made his way to the vault. There he discovered a cache of 1,000 half dollars which he gleefully threw over the top of the teller cage bars to Vinson as the Hoosier bandit giggled like a schoolboy. Unbeknownst to them, the bandits had stumbled upon the payroll of the “Real Silk Hosiery Company”, which was the nation’s largest shipper of c.o.d. parcel post packages whose headquarters were located in the Lockerbie Square area. (The building has since been converted to stylish apartments and condominiums.)

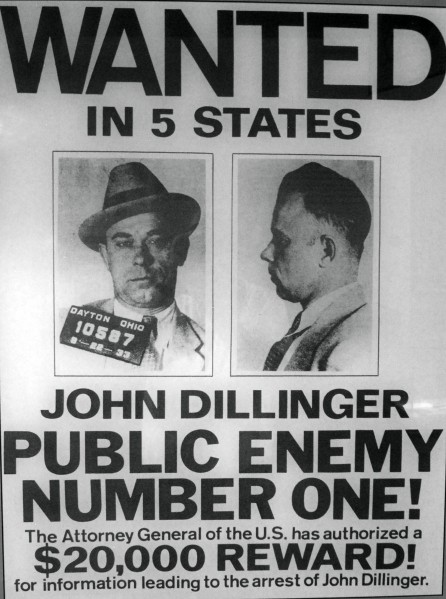

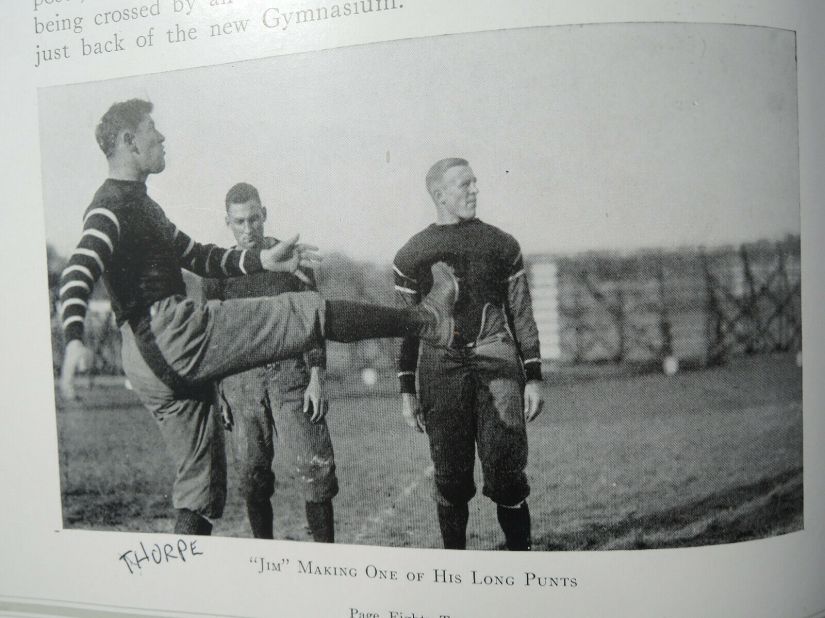

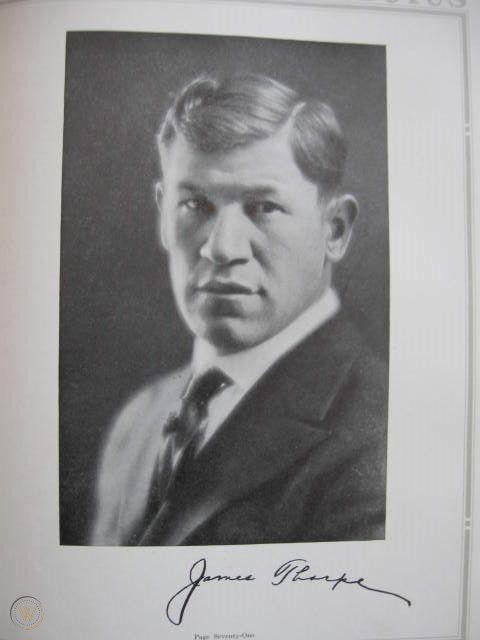

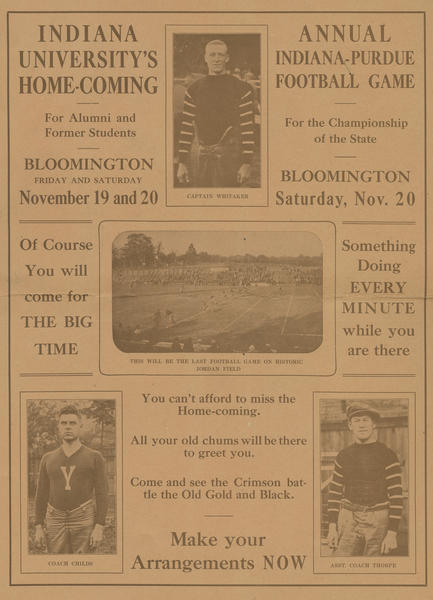

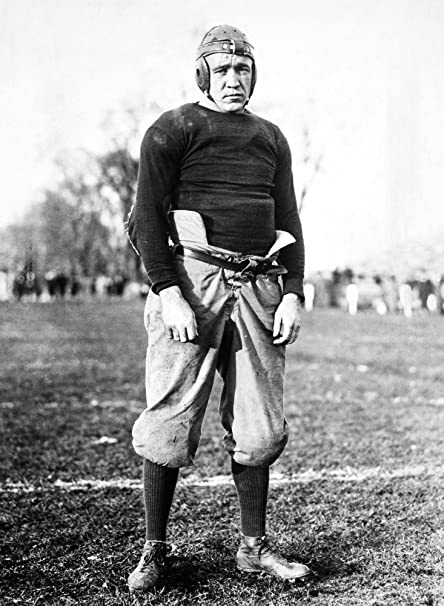

The Indianapolis star reported, “After some three weeks of anxious waiting, (John) McGraw’s national pastimers turn over to the University coaching staff one of the greatest athletes the world has ever known, James Thorpe. He and his family will arrive in this city Thursday evening at 7 o’clock. Thorpe will take up his duties as assistant coach Friday afternoon…Students, alumni and, in fact, the entire college world looks forward to the coming of this great athlete, with great eagerness to know exactly how his coaching will compare with his known ability as a player. In fact, the thing foremost in the minds of these men is, can this All-American star teach the Indiana backfield men the tricks that made him so famous at Carlisle?”

The Indianapolis star reported, “After some three weeks of anxious waiting, (John) McGraw’s national pastimers turn over to the University coaching staff one of the greatest athletes the world has ever known, James Thorpe. He and his family will arrive in this city Thursday evening at 7 o’clock. Thorpe will take up his duties as assistant coach Friday afternoon…Students, alumni and, in fact, the entire college world looks forward to the coming of this great athlete, with great eagerness to know exactly how his coaching will compare with his known ability as a player. In fact, the thing foremost in the minds of these men is, can this All-American star teach the Indiana backfield men the tricks that made him so famous at Carlisle?” Thorpe’s presence fired up the crowd as IU jumped out to a 34-0 lead by halftime. IU fans thrilled to the sight of Thorpe pacing the sideline. IU hammered Miami 41-0 in front of a huge crowd at Jordan Field. By the next Tuesday, Thorpe was finally getting in some real work with the kickers. The Daily Student noted, “Before the scrimmage, assistant coach Thorpe had the kickers out in the center of the arena instructing them in getting off their punts in good form…The Indian’s long, twisting spirals were not duplicated by either Scott or Whitaker, although both Crimson backs showed much improvement over past performances.”

Thorpe’s presence fired up the crowd as IU jumped out to a 34-0 lead by halftime. IU fans thrilled to the sight of Thorpe pacing the sideline. IU hammered Miami 41-0 in front of a huge crowd at Jordan Field. By the next Tuesday, Thorpe was finally getting in some real work with the kickers. The Daily Student noted, “Before the scrimmage, assistant coach Thorpe had the kickers out in the center of the arena instructing them in getting off their punts in good form…The Indian’s long, twisting spirals were not duplicated by either Scott or Whitaker, although both Crimson backs showed much improvement over past performances.” After the game, Thorpe spent his time on Jordan Field practicing kicking by himself. One IDS reporter noted on October 19th, “No one was around – there was no grandstand play – just a step, a quick swing of the leg and a double-thud as the ball hit ground and cleated shoe at the same instant. The kicker was “Jim” Thorpe, late addition to the Crimson coaching staff. He stood on the line which divides the gridiron into two equal portions, a little toward the sideline to avoid the mud. There was a flash of red and brown as his leg swung to meet the rising pigskin and away sailed the ball, end over end, squarely between the white posts at the end of the field. The long kick was accomplished with so much ease and grace that it appeared the least difficult feat in the world, but the big Indian merely smiled. It’s not “being done” on many gridirons this season, however, so old Jordan Field ought to feel mighty proud.”

After the game, Thorpe spent his time on Jordan Field practicing kicking by himself. One IDS reporter noted on October 19th, “No one was around – there was no grandstand play – just a step, a quick swing of the leg and a double-thud as the ball hit ground and cleated shoe at the same instant. The kicker was “Jim” Thorpe, late addition to the Crimson coaching staff. He stood on the line which divides the gridiron into two equal portions, a little toward the sideline to avoid the mud. There was a flash of red and brown as his leg swung to meet the rising pigskin and away sailed the ball, end over end, squarely between the white posts at the end of the field. The long kick was accomplished with so much ease and grace that it appeared the least difficult feat in the world, but the big Indian merely smiled. It’s not “being done” on many gridirons this season, however, so old Jordan Field ought to feel mighty proud.” On the day of the game, Nov. 20, Jordan Field was covered with sawdust to try to dry the water left by the snow, sleet and the rain of the past week. A crowd of more than 7,000 packed Jordan Field to see IU battle the Boilermakers in the old oaken bucket game. Purdue won 7-0. Thorpe put on another punting exhibition for the crowd at halftime. This one wasn’t as spirited as the Chicago exhibition the week before. Understandable because, Thorpe had a game to play the next day in Canton. Thorpe arrived in time for the second game in three weeks between Canton and Massillon, and he took over as head coach of the Bulldogs. In the game, Thorpe drop-kicked a field goal from 45 yards out in the first quarter and added a place kick of 38 yards in the third quarter to push Canton to a 6-0 victory.

On the day of the game, Nov. 20, Jordan Field was covered with sawdust to try to dry the water left by the snow, sleet and the rain of the past week. A crowd of more than 7,000 packed Jordan Field to see IU battle the Boilermakers in the old oaken bucket game. Purdue won 7-0. Thorpe put on another punting exhibition for the crowd at halftime. This one wasn’t as spirited as the Chicago exhibition the week before. Understandable because, Thorpe had a game to play the next day in Canton. Thorpe arrived in time for the second game in three weeks between Canton and Massillon, and he took over as head coach of the Bulldogs. In the game, Thorpe drop-kicked a field goal from 45 yards out in the first quarter and added a place kick of 38 yards in the third quarter to push Canton to a 6-0 victory. Jim Thorpe left Bloomington to continue his professional athletic career in baseball and football. He helped Canton win three Ohio League championships, reportedly sealing the 1919 title with a wind-assisted 95-yard punt late in the game. Thorpe eventually played for six NFL teams, although he never won a title, and he retired from football in 1928. He played Major League Baseball with the Giants, the Cincinnati Reds and the Boston Braves, compiling a career batting average of .252 in 289 games before retiring in 1919. He would be named the greatest athlete of the first half of the 20th century by the Associated Press and was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1951 and the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1963.

Jim Thorpe left Bloomington to continue his professional athletic career in baseball and football. He helped Canton win three Ohio League championships, reportedly sealing the 1919 title with a wind-assisted 95-yard punt late in the game. Thorpe eventually played for six NFL teams, although he never won a title, and he retired from football in 1928. He played Major League Baseball with the Giants, the Cincinnati Reds and the Boston Braves, compiling a career batting average of .252 in 289 games before retiring in 1919. He would be named the greatest athlete of the first half of the 20th century by the Associated Press and was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1951 and the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1963. One of Thorpe’s odd jobs was serving as a traveling softball umpire. When I was young collector, I purchased an old World War II softball in a box. It belonged to man who had received the ball as his own personal trophy for being named MVP of some long forgotten tournament. He mentioned that the ball had been signed by the tourney umpire. A man named Jim Thorpe. I opened the box and looked at the fountain pen signature, crisp as the day it had been signed. “You probably don’t know who that is.” the old man said. To which I answered, “Oh, I know who it is,” I answered. I’m an IU grad as are both of my children. And for a time, Jim Thorpe was one of us. That ball was sold off many years ago when the responsibility and expense of raising children trumped the need for sentimental objects. But the memory remains,

One of Thorpe’s odd jobs was serving as a traveling softball umpire. When I was young collector, I purchased an old World War II softball in a box. It belonged to man who had received the ball as his own personal trophy for being named MVP of some long forgotten tournament. He mentioned that the ball had been signed by the tourney umpire. A man named Jim Thorpe. I opened the box and looked at the fountain pen signature, crisp as the day it had been signed. “You probably don’t know who that is.” the old man said. To which I answered, “Oh, I know who it is,” I answered. I’m an IU grad as are both of my children. And for a time, Jim Thorpe was one of us. That ball was sold off many years ago when the responsibility and expense of raising children trumped the need for sentimental objects. But the memory remains,

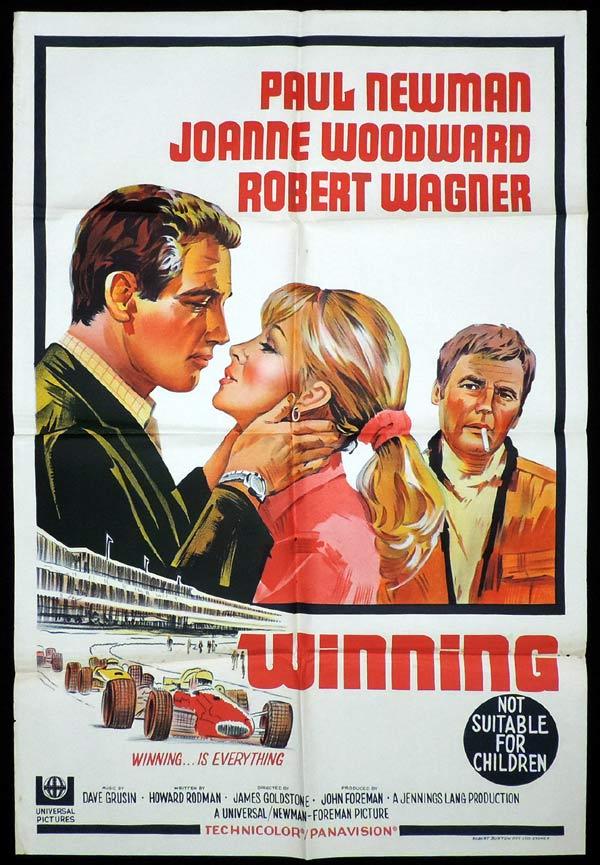

Even though I was very young, I can remember that in May of 1968, Hollywood came to town to film a major movie at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Although I didn’t know it at the time, the film was called “Winning,” and starred Paul Newman and his real-life wife, Joanne Woodward. The plot focused on an ambitious race driver determined to win the Indianapolis 500 in an effort to resurrect his flagging career. The film also starred Richard Thomas, soon to become more famous as “John Boy” on “The Waltons” TV series and Robert Wagner (of “Hart to Hart” TV fame). Several real-life racing figures-including the Speedway’s owner, Tony Hulman, and race driver Bobby Unser-portray themselves in the movie.

Even though I was very young, I can remember that in May of 1968, Hollywood came to town to film a major movie at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Although I didn’t know it at the time, the film was called “Winning,” and starred Paul Newman and his real-life wife, Joanne Woodward. The plot focused on an ambitious race driver determined to win the Indianapolis 500 in an effort to resurrect his flagging career. The film also starred Richard Thomas, soon to become more famous as “John Boy” on “The Waltons” TV series and Robert Wagner (of “Hart to Hart” TV fame). Several real-life racing figures-including the Speedway’s owner, Tony Hulman, and race driver Bobby Unser-portray themselves in the movie.