Original publish date: December 20, 2018

The Secret Service alerted Palm Beach police to be on the look out for Pavlick’s 1950 Buick. Around 9 p.m. on December 15, he was arrested as he entered the city via the Flagler Memorial Bridge onto Royal Poinciana Way. Palm Beach motorcycle police officer Lester Free stopped the light colored Buick for driving erratically on the wrong side of the road and for crossing the center line. When Free called in the license plates authorities realized they had Pavlick. Squad cars sped to the scene and surrounded the dynamite laden car and arrested the feeble old man without incident.

Once in custody Pavlick begin “singing like a bird.” He unashamedly admitted to his plans and detailed his movements and activities. Pavlick told the arresting officers, “Joe Kennedy’s money bought the White House and the Presidency. I had the crazy idea I wanted to stop Kennedy from being President.” When the Secret Service learned those details the agency was shocked. Secret Service Director U.E. Baughman later said it was the most serious assassination attempt since militant Puerto Rican pro-independence activists stormed the Capitol in an attempt on President Harry S Truman on November 1, 1950.

An Associated Press dispatch, dated December 16, 1960, announced: “A craggy-faced retired postal clerk who said he didn’t like the way John F. Kennedy won the election is in jail on charges he planned to kill the president-elect. Richard Pavlick, 73, was charged by the Secret Service with planning to make himself a human bomb and blow up Kennedy and himself.” It was only then that the public learned just how close Pavlick came to killing Kennedy.

Because Pavlick didn’t get near Kennedy on the day he was arrested, the story was not immediate national news. The story of Pavlick’s arrest happened the same day as a terrible airline disaster, known as the TWA Park Slope Plane Crash, in which two commercial planes collided over New York City, killing 134 people (including 6 on the ground). The plane crash story, the worst air disaster in U.S. history up to that time, occupied the national headlines and led the television and radio newscasts.

Because Pavlick didn’t get near Kennedy on the day he was arrested, the story was not immediate national news. The story of Pavlick’s arrest happened the same day as a terrible airline disaster, known as the TWA Park Slope Plane Crash, in which two commercial planes collided over New York City, killing 134 people (including 6 on the ground). The plane crash story, the worst air disaster in U.S. history up to that time, occupied the national headlines and led the television and radio newscasts.

The media was laser focused on the crash’s only survivor, 11-year-old Stephen Lambert Baltz who had been traveling alone on his way to spend Christmas in Yonkers with relatives. The boy was thrown from the plane into a snowbank where his burning clothing was extinguished. Barely alive and conscious, he was badly burned and had inhaled burning fuel. He died of pneumonia the next day. The assassination plot quickly faded from public attention.

Initially, Pavlick was charged with attempting to assassinate the new President. Pavlick told reporters that he was looking forward to the trial as an opportunity to voice his theories about the rigged election, Kennedy was a fraud and that he (Pavlick) was simply a patriot trying to save the Republic. For his part, Kennedy remained nonplussed about the attempt to kill him. On the day of the incident, JFK held a news conference outside his Palm Beach “Winter White House” to introduce his choice for Secretary of State, Dean Rusk. The sympathetic Kennedy urged the Justice Department, headed by his Attorney General / younger brother Bobby, not to bring Pavlick to trial. Political adversaries theorized that Kennedy and his advisers worried that a trial might turn Pavlick into a hero for right wing causes and may even inspire copy cats.

On January 27, 1961, a week after Kennedy was inaugurated as the 35th President of the United States, Pavlick was committed to the United States Public Health Service mental hospital in Springfield, Missouri. He was indicted for threatening Kennedy’s life seven weeks later. The case would drag on for years without resolution. Belmont Postmaster Thomas M. Murphy had been promised that he would remain an anonymous informant, but was quickly identified as the tipster by the media. At first he was hailed as a hero and his boss, the Postmaster General, commended his actions. Congress even passed a resolution praising him. But then, fervent right wing publisher William Loeb of the Manchester Union Leader, New Hampshire’s influential state-wide newspaper, began defending Pavlick. Turns out, Loeb held many of the same opinions about Kennedy as the would-be assassin.

On January 27, 1961, a week after Kennedy was inaugurated as the 35th President of the United States, Pavlick was committed to the United States Public Health Service mental hospital in Springfield, Missouri. He was indicted for threatening Kennedy’s life seven weeks later. The case would drag on for years without resolution. Belmont Postmaster Thomas M. Murphy had been promised that he would remain an anonymous informant, but was quickly identified as the tipster by the media. At first he was hailed as a hero and his boss, the Postmaster General, commended his actions. Congress even passed a resolution praising him. But then, fervent right wing publisher William Loeb of the Manchester Union Leader, New Hampshire’s influential state-wide newspaper, began defending Pavlick. Turns out, Loeb held many of the same opinions about Kennedy as the would-be assassin.

Loeb very publicly protested that Pavlick was being persecuted and denied his sixth amendment right to a speedy trial. Loeb’s newspaper disputed the insanity ruling and insisted the defendant have his day in court. Once the newspaper took up Pavlick’s cause, Murphy and his family began receiving hate mail, death threats and anonymous phone calls at all hours of the day and night accusing him of helping to frame Pavlick and for “railroading an innocent man.” The abuse continued for years after Murphy’s November 14, 2002 death at age 76. Even today, the surviving Murphy children are targeted by right-wing groups whenever the case gets a new round of public attention.

Loeb very publicly protested that Pavlick was being persecuted and denied his sixth amendment right to a speedy trial. Loeb’s newspaper disputed the insanity ruling and insisted the defendant have his day in court. Once the newspaper took up Pavlick’s cause, Murphy and his family began receiving hate mail, death threats and anonymous phone calls at all hours of the day and night accusing him of helping to frame Pavlick and for “railroading an innocent man.” The abuse continued for years after Murphy’s November 14, 2002 death at age 76. Even today, the surviving Murphy children are targeted by right-wing groups whenever the case gets a new round of public attention.

Charges against Pavlick were dropped on December 2, 1963, ten days after JFK’s assassination. Judge Emett Clay Choate ruled that Pavlick was incapable of telling right from wrong-the legal definition of insanity-but nonetheless ordered that the would-be assassin remain in the Missouri mental hospital. The federal government officially dropped charges in August 1964, and Pavlick was released from custody on December 13, 1966. Pavlick had been institutionalized for nearly six years after his arrest, and three years after Oswald killed John F. Kennedy.

After his release, Pavlick returned to Belmont. He began parking in front of the Murphy house seated in his car for hours every day watching it. But since there were no laws on the books against stalking in 1966, police could do little to inhibit the suspicious activities. Pavlick always denied any malicious intent and was never found to be armed. Belmont police officers would park their squad cars nearby to keep an eye on Pavlick, sometimes for several hours at a stretch. If the officer was called away, the family felt unsafe. Pavlick continued his old habit of letter writing and phone calling media outlets and government officials with rants proclaiming his innocence yet strangely justifying his actions. Pavlick died at the age of 88 on Veteran’s Day, November 11, 1975 at the Veterans Administration Hospital in Manchester, N.H. He remained unrepentant to the end.

Pavlick is unique among Presidential Assassins (would-be and otherwise) for one reason: his age. Of the four successful Presidential assassins, Lee Harvey Oswald was 24; John Wilkes Booth, 26; Leon Czolgosz was 28 when he assassinated William McKinley, and Charles Guiteau 39 when he murdered James A. Garfield. Of those unsuccessful few, Richard Lawrence was 35 when he attacked Andrew Jackson, John F. Schrank was 36 when he shot Teddy Roosevelt, Giuseppe “Joe” Zangara was 32 when he attempted to assassinate then-President-elect Franklin D. Roosevelt, Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme was 27 and Sarah Jane Moore 45 when they individually tried to shoot Gerald Ford and John Hinckley Jr. was 25 when he shot Ronald Reagan. Richard Paul Pavlick was 73 years old at the time of his attempt.

In today’s 24-hour-a-day, scandal-driven media environment, it is hard to believe that an incident of this magnitude would go unnoticed. Or would it? Sure, we all know about the very public assassination threats and attempts once they are out in the open. But what about those threats that are never reported? In Pavlick’s case, the public learned about it from the would-be assassin himself. He was proud of his plans and, after capture, boasted about it to anyone that came within earshot. The answer can be found in the name of the organization protecting the President: The Secret Service is, well, secret.

In today’s 24-hour-a-day, scandal-driven media environment, it is hard to believe that an incident of this magnitude would go unnoticed. Or would it? Sure, we all know about the very public assassination threats and attempts once they are out in the open. But what about those threats that are never reported? In Pavlick’s case, the public learned about it from the would-be assassin himself. He was proud of his plans and, after capture, boasted about it to anyone that came within earshot. The answer can be found in the name of the organization protecting the President: The Secret Service is, well, secret.

Although records prior to the “information age” are hard to come by, former Secret Service Agent Floyd M. Boring (who worked for three presidents and was with Franklin D. Roosevelt when he died at Warm Springs, Georgia) stated that during the period 1949–1950, the Secret Service investigated 1,925 threats against Harry S Truman. Another study, in the September 7, 1970 issue of Time magazine, claimed the number of annual threats against the President rose from 2,400 in 1965 to 12,800 in 1969.

The Secret Service does not generally place a number on the threats they receive, nor do they feel the need to investigate each and every one nowadays. On June 1, 2017 CBS news reported “Threats against President Trump for his first six months in office are tracking about six to eight per day…It’s about the same number of threats made against former Presidents Obama and George W. Bush while they were in office.” Another report contrarily states that President Barack Obama received more than 30 potential death threats a day. That was an increase of 400% from the 3,000 a year or so under President George W. Bush. A recent news story reported that In the first 12 days of Donald Trump’s administration, 12,000 assassination tweets alone were recorded. The vast majority of the tweets are jokes or sarcastic jibes, but still, that is a BIG number.

Today, Presidential death threats are handled by approximately 3,200 special agents and an additional 1,300 uniformed officers guard the White House, the Treasury building and foreign diplomatic missions in Washington. So it can be assumed that these crackpots in search of lasting infamy are a lot more common than we think and will, sadly, continue to pop up from time-to-time. The best we can hope for is that the vast majority will remain unknown and forgotten. Like Richard Paul Pavlick.

nowhere. He lived alone and had no family to speak of. Locals in his hometown of Belmont remember him for his angry political rants and public outbursts at local public meetings. After accusing the town of poisoning his water, Pavlick once confronted the local water company supervisor with a gun, which was then promptly confiscated. His central complaint was that the American flag was not being displayed appropriately. He often criticized the government and blamed most of the country’s problems on the Catholics. But the perpetually grumpy, prune-faced Pavlick focused most of his anger on the Kennedy family and their “undeserved” wealth.

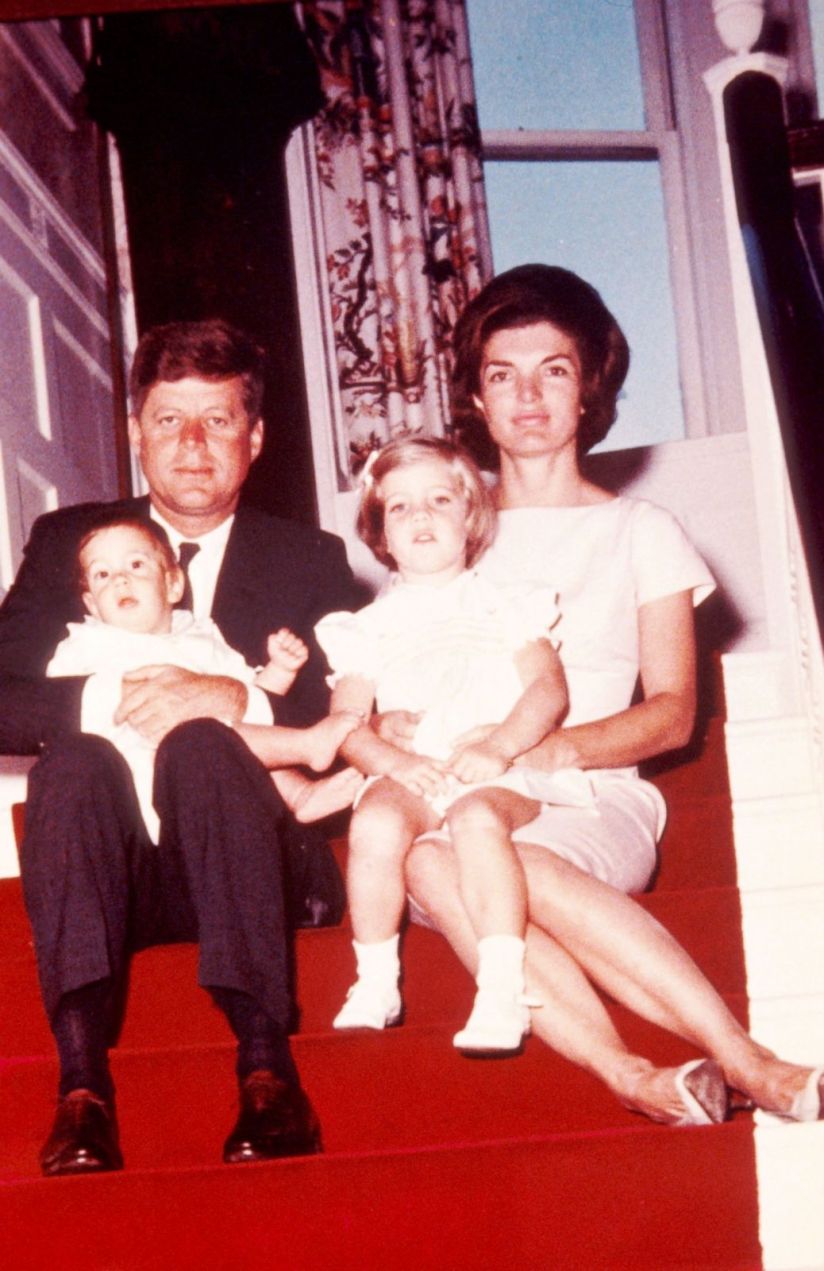

nowhere. He lived alone and had no family to speak of. Locals in his hometown of Belmont remember him for his angry political rants and public outbursts at local public meetings. After accusing the town of poisoning his water, Pavlick once confronted the local water company supervisor with a gun, which was then promptly confiscated. His central complaint was that the American flag was not being displayed appropriately. He often criticized the government and blamed most of the country’s problems on the Catholics. But the perpetually grumpy, prune-faced Pavlick focused most of his anger on the Kennedy family and their “undeserved” wealth. Luckily for Mr. Kennedy, fate stepped in to save the day… and the President-elect’s life. Kennedy did not leave his house alone that morning. Much to Pavlick’s surprise, JFK opened the door holding the hand of his 3-year-old daughter Caroline alongside his wife, Jacqueline who was holding the couple’s newborn son John, Jr., less than a month old. While Pavlick hated John F. Kennedy, he hadn’t signed up to kill Kennedy’s family. So Pavlick eased his itchy trigger-finger off the detonator switch and let the Kennedy limousine glide harmlessly past his car. No one realized that the beat-up old Buick and the white haired old man in it was literally a ticking time bomb. Pavlick glared at the car as it slipped away and decided he would try again another day. Luckily, he never got a second chance.

Luckily for Mr. Kennedy, fate stepped in to save the day… and the President-elect’s life. Kennedy did not leave his house alone that morning. Much to Pavlick’s surprise, JFK opened the door holding the hand of his 3-year-old daughter Caroline alongside his wife, Jacqueline who was holding the couple’s newborn son John, Jr., less than a month old. While Pavlick hated John F. Kennedy, he hadn’t signed up to kill Kennedy’s family. So Pavlick eased his itchy trigger-finger off the detonator switch and let the Kennedy limousine glide harmlessly past his car. No one realized that the beat-up old Buick and the white haired old man in it was literally a ticking time bomb. Pavlick glared at the car as it slipped away and decided he would try again another day. Luckily, he never got a second chance.

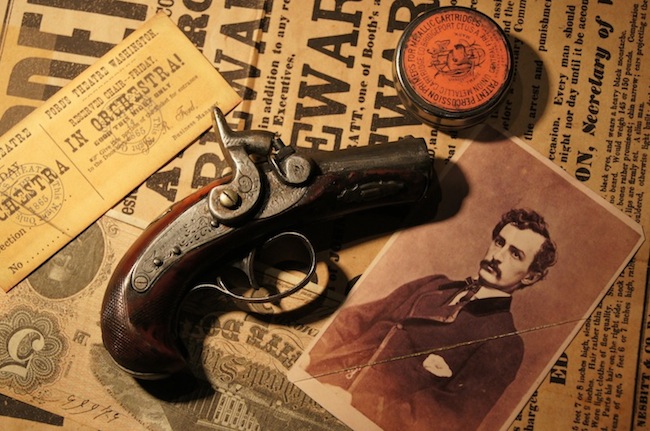

The ALPLM’s “problems” began back in 2007 when it purchased the famous Taper collection for $23 million. “The collection is amazing,” says Sam, “the Lincoln top hat and bloodied gloves seem to be the items that resonate most with people, but the collection is much more than that.” Dr. Wheeler says that the uniqueness of the Taper collection centers around its emphasis on assassination related items, a field that had been largely ignored by Lincoln collectors at that time of its assemblage. The collection was created by Louise Taper, daughter-in-law of Southern California real estate magnate S. Mark Taper. She created the exhibition The Last Best Hope of Earth: Abraham Lincoln and the Promise of America which was at the Huntington Library from 1993–1994 and at the Chicago Historical Society from 1996-1997.

The ALPLM’s “problems” began back in 2007 when it purchased the famous Taper collection for $23 million. “The collection is amazing,” says Sam, “the Lincoln top hat and bloodied gloves seem to be the items that resonate most with people, but the collection is much more than that.” Dr. Wheeler says that the uniqueness of the Taper collection centers around its emphasis on assassination related items, a field that had been largely ignored by Lincoln collectors at that time of its assemblage. The collection was created by Louise Taper, daughter-in-law of Southern California real estate magnate S. Mark Taper. She created the exhibition The Last Best Hope of Earth: Abraham Lincoln and the Promise of America which was at the Huntington Library from 1993–1994 and at the Chicago Historical Society from 1996-1997. “Bottom line,” Sam says, “we need to keep the collection here. That is our first priority.” It is easy to see how important this collection is to Dr. Wheeler by simply watching his eyes as he speaks. To Wheeler, the collection is not just a part of the museum, it is a part of the state of Illinois. Sam relates how when he speaks to groups, which he does quite regularly on behalf of the ALPLM, he often reaches into the vault to bring along pieces from the Taper collection to fit the topic. “People love seeing these items. It gives them a direct connection to Lincoln.” states Wheeler.

“Bottom line,” Sam says, “we need to keep the collection here. That is our first priority.” It is easy to see how important this collection is to Dr. Wheeler by simply watching his eyes as he speaks. To Wheeler, the collection is not just a part of the museum, it is a part of the state of Illinois. Sam relates how when he speaks to groups, which he does quite regularly on behalf of the ALPLM, he often reaches into the vault to bring along pieces from the Taper collection to fit the topic. “People love seeing these items. It gives them a direct connection to Lincoln.” states Wheeler. Hoosiers may ask, why doesn’t the ALPLM just ask the state of Illinois for the money? After all, with 300,000 visitors annually, the Lincoln Library Museum is one of the most popular tourist sites in the state of Illinois and is prominently featured in all of their state tourism ads. Well, the state is billions of dollars in debt despite approving a major income-tax increase last summer and as of the time of this writing, has yet to put together a budget. To the casual observer, one would think that financial stalemate between the state and the museum would be a no-brainer when you consider that the ALPLM has drawn more than 4 million visitors since opening in 2005. The truth is a little more complicated than that. Illinois State government runs and funds the Lincoln library and museum. The separately run foundation raises private funds to support the presidential complex. The foundation, which is not funded by the state, operates a gift store and restaurant but has little role in the complex’s operations, programs and oversight.

Hoosiers may ask, why doesn’t the ALPLM just ask the state of Illinois for the money? After all, with 300,000 visitors annually, the Lincoln Library Museum is one of the most popular tourist sites in the state of Illinois and is prominently featured in all of their state tourism ads. Well, the state is billions of dollars in debt despite approving a major income-tax increase last summer and as of the time of this writing, has yet to put together a budget. To the casual observer, one would think that financial stalemate between the state and the museum would be a no-brainer when you consider that the ALPLM has drawn more than 4 million visitors since opening in 2005. The truth is a little more complicated than that. Illinois State government runs and funds the Lincoln library and museum. The separately run foundation raises private funds to support the presidential complex. The foundation, which is not funded by the state, operates a gift store and restaurant but has little role in the complex’s operations, programs and oversight.

Original publish date: July 20, 2017

Original publish date: July 20, 2017 Another of the letters, dated Dec. 10, 1902, touched me personally because it was written by the sister of Louis Weichmann, the main government witness at the trial of the conspirators. Weichmann lived in Mrs. Surratt’s boarding house and many believe it was Weichmann’s testimony that got Mary Surratt hung. Weichmann moved to Anderson Indiana after the trial and founded Anderson business college. He is buried in Anderson’s St. Francis cemetery in an unmarked grave. “Dear Sir-I am sending you a copy of Sunday’s Indianapolis Journal containing a confession of one of the conspirators of President Lincoln….With best regards from our family, I remain Sincerely yours, Mrs. C.O. Crowley Sister of the late L.J. Wiechmann.” Curiously, Mrs. Crowley misspelled her own maiden name in her letter.

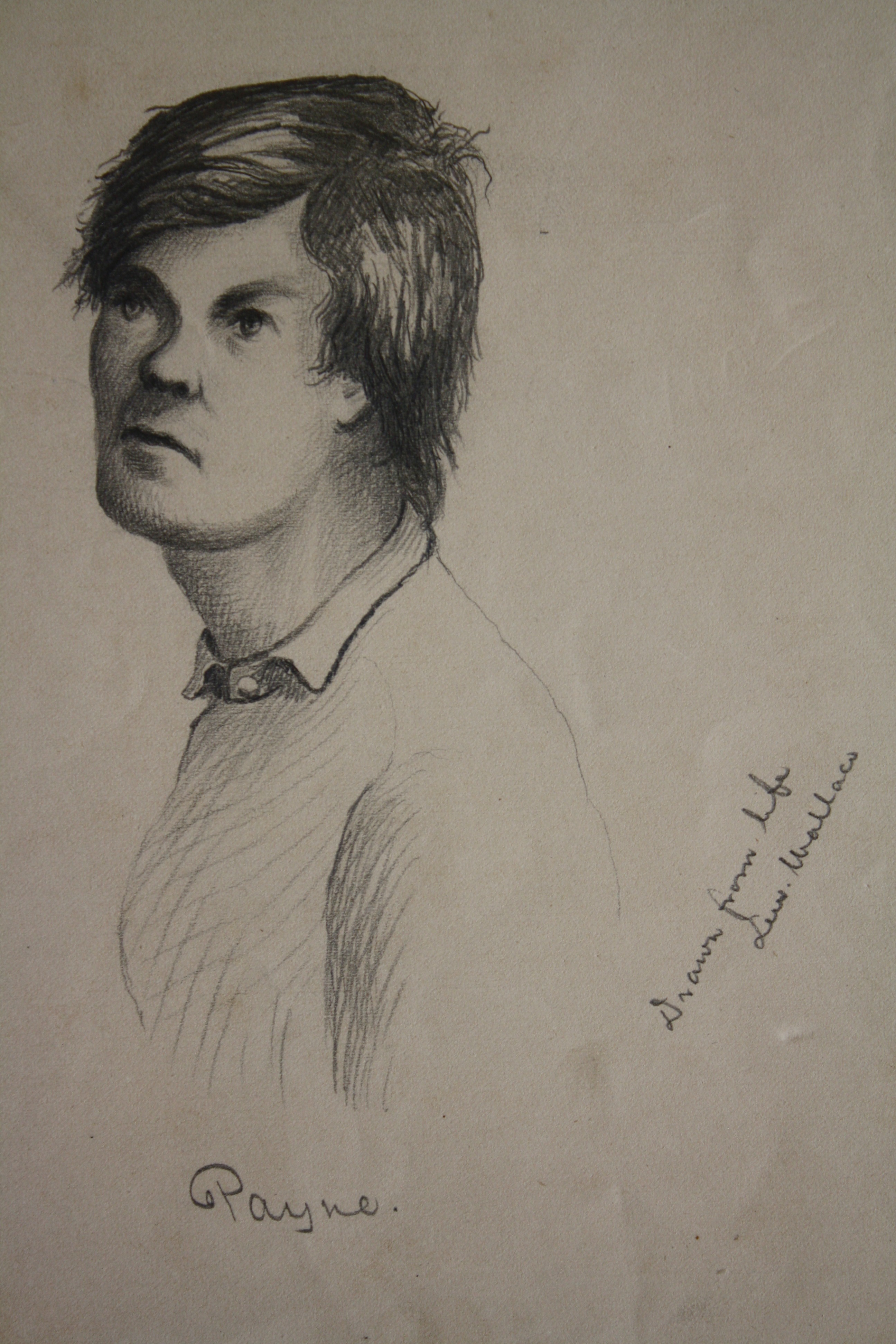

Another of the letters, dated Dec. 10, 1902, touched me personally because it was written by the sister of Louis Weichmann, the main government witness at the trial of the conspirators. Weichmann lived in Mrs. Surratt’s boarding house and many believe it was Weichmann’s testimony that got Mary Surratt hung. Weichmann moved to Anderson Indiana after the trial and founded Anderson business college. He is buried in Anderson’s St. Francis cemetery in an unmarked grave. “Dear Sir-I am sending you a copy of Sunday’s Indianapolis Journal containing a confession of one of the conspirators of President Lincoln….With best regards from our family, I remain Sincerely yours, Mrs. C.O. Crowley Sister of the late L.J. Wiechmann.” Curiously, Mrs. Crowley misspelled her own maiden name in her letter. Included within that collection was a group of several dozen items that once belonged to Osborn Oldroyd himself. This included correspondence from Anderson’s Louis Weichmann to Oldroyd about shared information for books about Abraham Lincoln both men were simultaneously working on as well as photos and several handwritten eyewitness accounts of the assassination of President Lincoln. My personal favorite was a pencil drawing of Lincoln Conspirator Lewis Thornton Powell drawn by Crawfordsville, Indiana’s General Lew Wallace.

Included within that collection was a group of several dozen items that once belonged to Osborn Oldroyd himself. This included correspondence from Anderson’s Louis Weichmann to Oldroyd about shared information for books about Abraham Lincoln both men were simultaneously working on as well as photos and several handwritten eyewitness accounts of the assassination of President Lincoln. My personal favorite was a pencil drawing of Lincoln Conspirator Lewis Thornton Powell drawn by Crawfordsville, Indiana’s General Lew Wallace. Original publish date: February 19, 2016

Original publish date: February 19, 2016 That afternoon, Booth sat down and wrote a letter to the editor of a Washington D.C. newspaper called the National Intelligencer. In it, he explained that his plans had changed from kidnapping Lincoln to assassinating Lincoln. He signed the letter not only with his own name but also three of his co-conspirators: Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, and David Herold. Then he got up and walked his rented horse down Fourteenth Street.

That afternoon, Booth sat down and wrote a letter to the editor of a Washington D.C. newspaper called the National Intelligencer. In it, he explained that his plans had changed from kidnapping Lincoln to assassinating Lincoln. He signed the letter not only with his own name but also three of his co-conspirators: Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, and David Herold. Then he got up and walked his rented horse down Fourteenth Street.

Apparently Booth visited Mathews and Warwick at the Petersen house and both rented the Lincoln death room on numerous occasions. Both actors recalled Booth visiting them there, stretching out on the bed, laughing and telling stories, chomping on a cigar or with his pipe hooked in his mouth. There are several unconfirmed claims that Mathews was actually staying in an upstairs room at the Petersen House on the night of Lincoln’s assassination. The accounts are speculative at best but tantalizing to be sure. If that were the case, then Mathews burned Booth’s confessional letter in a fireplace just feet away from the dying President.

Apparently Booth visited Mathews and Warwick at the Petersen house and both rented the Lincoln death room on numerous occasions. Both actors recalled Booth visiting them there, stretching out on the bed, laughing and telling stories, chomping on a cigar or with his pipe hooked in his mouth. There are several unconfirmed claims that Mathews was actually staying in an upstairs room at the Petersen House on the night of Lincoln’s assassination. The accounts are speculative at best but tantalizing to be sure. If that were the case, then Mathews burned Booth’s confessional letter in a fireplace just feet away from the dying President.