Original publish date: July 12, 2018

Recently I was fortunate enough to take a tour of an American treasure housed within the Maryland Medical Examiner’s Office in Baltimore, Maryland. What, you ask? An American treasure in a medical examiner’s office? Yes dear reader, let me share with you a story about the coolest display you’re ever likely to find in any government office, anywhere. This is the story of the “Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death.” On the fourth floor, room 417 is marked “Pathology Exhibit” and it holds 18 dollhouses of death. These meticulous teaching dioramas, dating from the World War II era, are an engineering marvel in dollhouse miniature and easily the most charmingly macabre tableau I’ve ever seen.

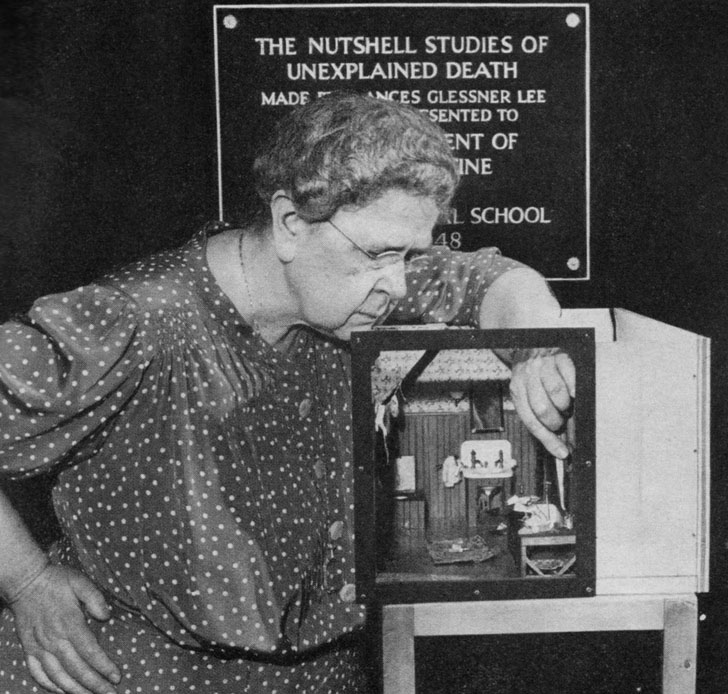

These dioramas were created by Frances Glessner Lee (1878–1962) over the course of 5 years between 1943 and 1948. Glessner Lee was a pioneer in the burgeoning field of forensic science and a trailblazer for women’s rights. She used a sizable inheritance to establish a department of legal medicine at Harvard Medical School in 1936. She donated the first of the Nutshell Studies in 1946 for use in lectures on the subject of crime scene investigation. Glessner Lee named her studies nutshells because they were designed to “convict the guilty, clear the innocent, and find the truth in a nutshell.” She instructed her students to study each scene methodically by “moving the eyes in a clockwise spiral” before drawing conclusions based on visual evidence. Crime-scene investigators had 90 minutes to study each diorama.

I was fortunate to have Bruce Goldfarb, Special Assistant for the Office of the Chief M.E., as my personal tour guide. Bruce, a former EMT, newspaper writer and accomplished author many times over, knows more about the Nutshell Studies than any one else in the Clipper City. “There are 18 dioramas in our collection and another is housed in a museum in Littleton, New Hampshire.” Bruce says, “Glessner Lee was an heiress to the International Harvester fortune and a dedicated model-maker. Each diorama cost as much to make as a full sized house.” Each model cost about US$3,000–4,500 to create which, when calculated for inflation, translates to $ 40,000 to $ 60,000 today.

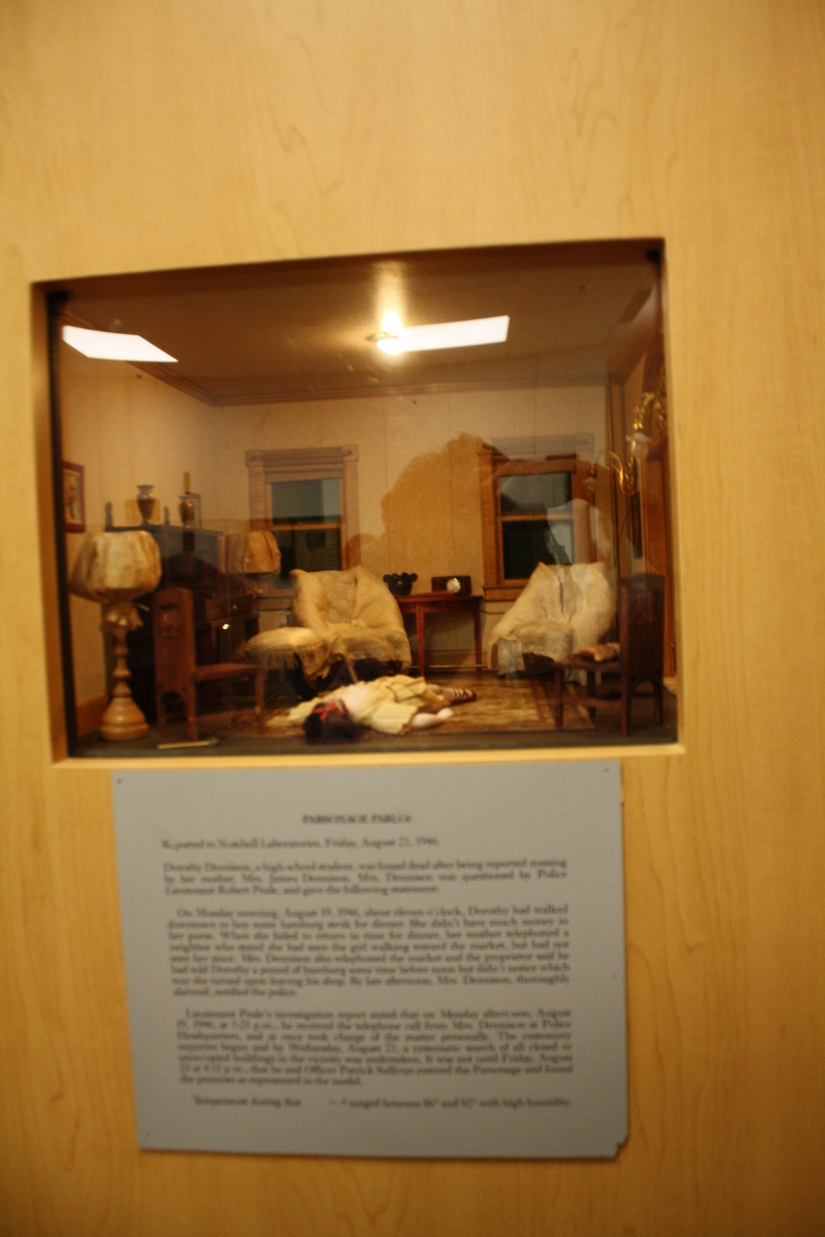

Each exquisitely detailed miniature diorama (1 inch equals 1 foot or a 1:12 scale) depicts a different true crime scene and are so well done that they are still used for forensic training today. Bruce explains, “These are not famous crime scenes. They are local scenes chosen by Frances to tell a story using composites of actual court cases. They are designed to teach young investigators how to examine and preserve a crime scene properly.”

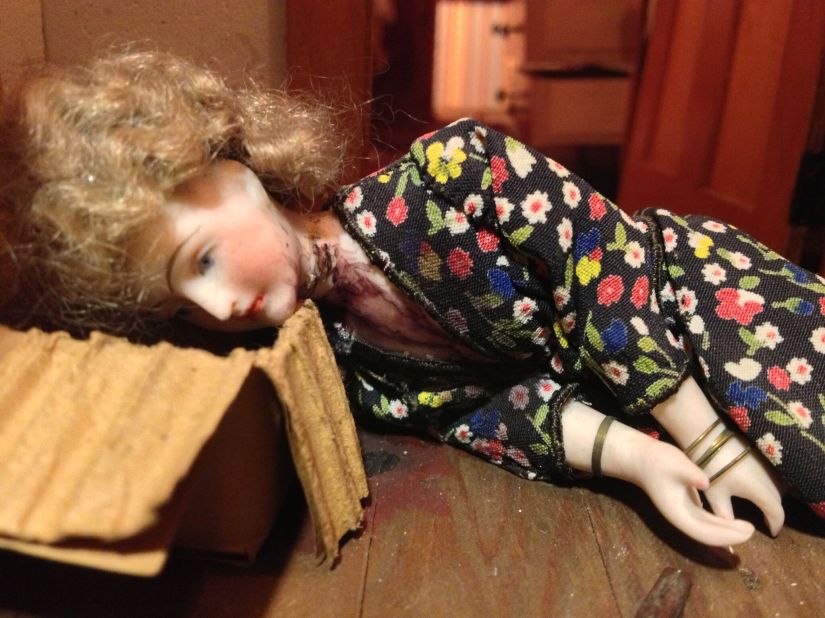

Housed in impressive looking wood and glass locked cases, they are not unlike the ancient penny arcade mechanical machines recalled by every baby boomer’s childhood. Except these scenes are populated by dead bodies, gruesome instruments of death and startling realistic blood spatter patterns. The scenes take place in attics, barns, bedrooms, log cabins, bathrooms, garages, kitchens, parsonages, saloons, jails, porches and even a woodman’s shack. Sometimes, it’s easy to determine the cause of death, but look closer and conclusions are tested. There is more than meets the eye in the Nutshell Studies and any object could be a clue. Every element of the dioramas-angles of minuscule bullet holes, placements of window latches, discoloration of painstakingly painted miniature corpses-challenges the powers of observation and deduction.

Housed in impressive looking wood and glass locked cases, they are not unlike the ancient penny arcade mechanical machines recalled by every baby boomer’s childhood. Except these scenes are populated by dead bodies, gruesome instruments of death and startling realistic blood spatter patterns. The scenes take place in attics, barns, bedrooms, log cabins, bathrooms, garages, kitchens, parsonages, saloons, jails, porches and even a woodman’s shack. Sometimes, it’s easy to determine the cause of death, but look closer and conclusions are tested. There is more than meets the eye in the Nutshell Studies and any object could be a clue. Every element of the dioramas-angles of minuscule bullet holes, placements of window latches, discoloration of painstakingly painted miniature corpses-challenges the powers of observation and deduction.

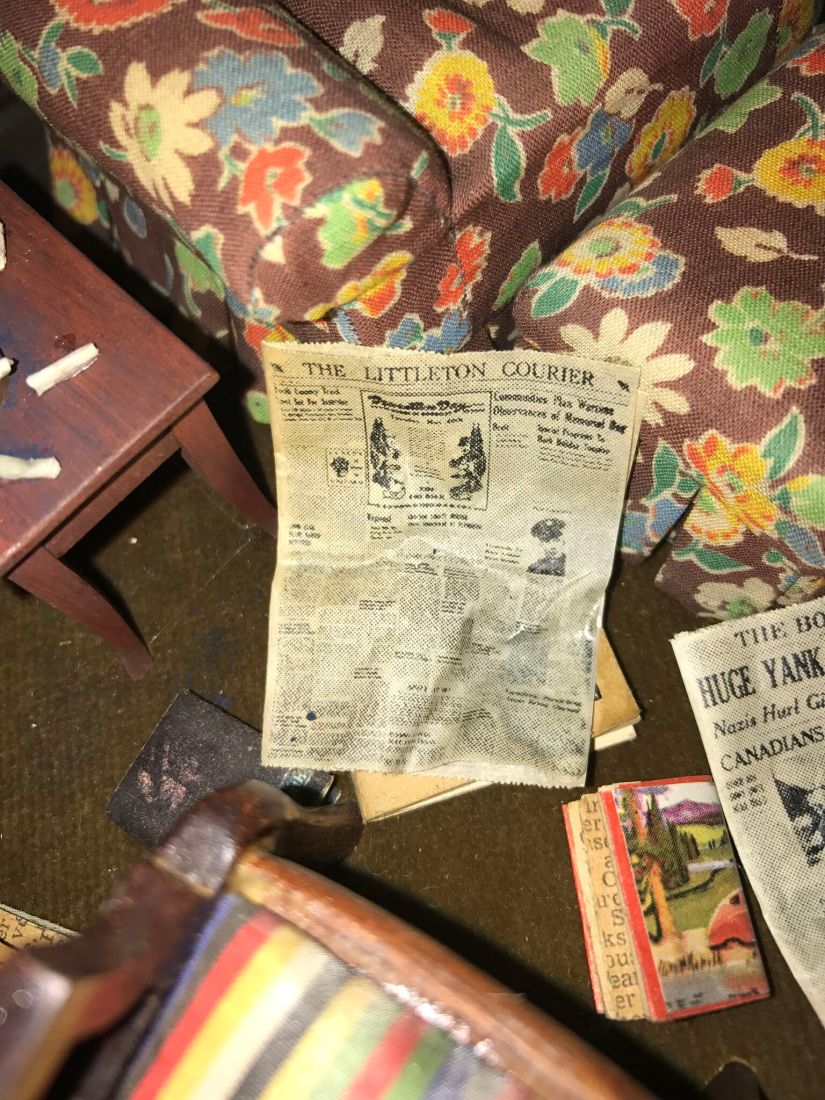

Bruce says, “Look at the miniature sewing machine (about the size of your thumbnail) it’s threaded. There is graffiti on the jail cell walls. The newspapers (less than the size of a postage stamp) are real. Each one had to be printed on a tiny press, the newsprint is immeasurably small. The Life magazine cover is accurate to the week of the crime. The ant-sized cigarettes are hand rolled and burnt on the end. Amazing!” Bruce, who came to the M.E.’s office in 2012, says that although he’s been over every inch of each diorama, he is still making new discoveries.

Bruce says, “Look at the miniature sewing machine (about the size of your thumbnail) it’s threaded. There is graffiti on the jail cell walls. The newspapers (less than the size of a postage stamp) are real. Each one had to be printed on a tiny press, the newsprint is immeasurably small. The Life magazine cover is accurate to the week of the crime. The ant-sized cigarettes are hand rolled and burnt on the end. Amazing!” Bruce, who came to the M.E.’s office in 2012, says that although he’s been over every inch of each diorama, he is still making new discoveries.

Bruce credits a recent exhibition of the Nutshell Studies at the Smithsonian for reinvigorating interest in the displays among the public. The dioramas were exhibited at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian’s American Art Museum in Washington, DC from October 20, 2017 to January 28, 2018. When I asked if they would ever be put on public display again, Bruce answers quickly, “Never. That is the last time they will be available to the general public. This is a classroom, not a gallery. The studies won’t leave this room again.” He continues, “The Smithsonian people really helped in our preservation efforts. They had expertise far beyond our knowledge.” Bruce especially credits Smithsonian conservator Ariel O’Connor for her expertise, “Ariel is the only woman to have entered the Apollo 11 capsule and only the 6th person overall. She was lowered Tom Cruise / Mission Impossible style into the capsule to retrieve a bag left under the seat by Neil Armstrong.”

As informative as Mr. Goldfarb is on the dioramas, his eyes really light up when it comes to the artist. He explains “Lee was the first female police captain in the U.S. and is considered the mother of forensic science.” Lee’s original commission as captain hangs nearby on the wall. Bruce delights in telling the story of how a woman co-opted traditionally feminine crafts to advance the male-dominated field of police investigation and to establish herself as one of the founders of “legal medicine”, what we now call forensic science. “These studies are not puzzles waiting to be solved. They are designed to teach police officers to handle, observe and assess crime scenes. Frances wanted the investigator to get a sense of who these people were by deciphering the residual clues found in the surroundings.”

The Nutshell Studies made their debut at the homicide seminar in Boston in 1945. It was the first of it’s kind. Bruce says, “Frances’ intention was for Harvard University to do for crime scene investigation what they had done for their famous business school. When Frances died in 1962, support evaporated and by 1966, the department of legal medicine at Harvard was dissolved.” When asked how the displays made the trip from Harvard yard to Baltimore, Bruce states, “That’s a good question. When Harvard planned to throw them away, longtime medical examiner Russell S. Fisher brought them here in 1968. Fisher was a legend and a former student of Frances Glessner Lee. Fisher was one of the doctors called in to examine John F. Kennedy’s head wounds.”

The Nutshell Studies made their debut at the homicide seminar in Boston in 1945. It was the first of it’s kind. Bruce says, “Frances’ intention was for Harvard University to do for crime scene investigation what they had done for their famous business school. When Frances died in 1962, support evaporated and by 1966, the department of legal medicine at Harvard was dissolved.” When asked how the displays made the trip from Harvard yard to Baltimore, Bruce states, “That’s a good question. When Harvard planned to throw them away, longtime medical examiner Russell S. Fisher brought them here in 1968. Fisher was a legend and a former student of Frances Glessner Lee. Fisher was one of the doctors called in to examine John F. Kennedy’s head wounds.”

Each study includes a descriptive crime scene report placard (written by Lee to accompany each case) containing a general outline of the crime, parties involved and date. But the solutions remain a secret. One such placard reads: “Robert Judson, a foreman in a shoe factory, his wife, Kate Judson, and their baby, Linda Mae Judson, were discovered dead by Paul Abbott, a neighbor.”

One model shows farmer Eben Wallace hanged in a hay-filled barn. One depicts a man shot to death in a log cabin, another shows a charred body in a burnt home, another, a body splattered face-down on the sidewalk outside a three-story apartment complex and still another reveals the decomposing body of “Mrs. Rose Fishman,” found in a pink bathroom in 1942. The scenes are accurate to the tiniest of details, including the appropriate lighting. “Frances was very ingenious in her lighting choices. There were no LED lighting options available. She used turn signal bulbs, Christmas tree lights, flashlight bulbs, anything she could find. Sometimes it came down to the color of the bulb or a particular paint color to achieve appropriate mood lighting.” says Bruce. “The blood pools and spatter are actually finger nail polish, which took us forever to figure out.”

While perusing these fascinating dioramas, it’s easy to forget where you are. Researchers who work in the $43 million Forensic Medical Center call the state-of-the-art facility the “Bat Cave.” It is the largest free-standing medical examiner’s office in the country and home to some 80 full-time employees, many of them pathologists, who analyze death in minute scientific detail, much like the Nutshell Studies themselves. Here, the state of Maryland learns the facts behind thousands of deaths each year.

I inform Bruce that the last time I was in Baltimore was on April 15, 2015 during the 150th anniversary of the Civil War. It was 3 days after the tragic death of Freddie Gray that sparked Civil Rights protests in the city and all across the country. My visit this time came just 3 days after the Capital Gazette newspaper shootings in Annapolis. Bruce pauses, shakes his head slightly and says, “Yes, we were very involved in the Freddie Gray incident and we’re working on the Capital Gazette shootings downstairs right now.”

In a typical summer, the M.E.’s office receives 13 to 18 bodies each day (more than 8,000 per year). It is the sole medical examiner’s office for the entire state. Homicide accounts for about 14 % of deaths, suicide for 12 % and accidents for 27 %. The first floor of the building serves as a garage that can be transformed into a mass casualty center. A large classroom on the fourth floor, with banks of desks and communication connections, can become an emergency command center during disasters. It’s like a hospital where patients are getting a physical exam, one day too late.

Bruce says the Nutshell Studies are an integral part of the M.E.’s popular 5-day homicide seminar every April. The seminars are limited to 90 people and are routinely filled to capacity. He reveals that the courses are likely to be expanded this October. “The seminars are not pass or fail, they are designed as a team exercise. Each team member is paired up with strangers. They are conducted the same way that Frances did them back in 1945. Each graduate receives a ‘Harvard Associates in Police Sciences’ diploma and a class photo. Historically, police officers and journalists do well.” Bruce says with a wry smile.

However, the Nutshell Studies are not the only visual aids created by Frances on display in the M.E.’s office. The walls of the entryway to room 417 are lined with 48 incredibly realistic looking bullet wound patterns and the conference room has 3 life-size heads with bullet wounds, slashed throats and a reconstructed face. Cases contain cremated remains, shoes worn by people struck by lightning, exploded oxygen tanks and even a motorcycle helmet from a crash victim who died in an accident. But wait, there’s more.

Bruce asks, “Would you like to see the Scarpetta House?” Accompanied by official tech advisers Kris & Roger Branch and my photographer wife Rhonda, I answered “Absolutely” even though I had no idea what lay in store for us. Bruce explains that the Scarpetta house is an enclosed space decorated like a typical model home complete with a swing set and wooden deck “outside”, a furnished living room, bedroom, bathroom, kitchen and laundry room “inside.” It was donated by novelist Patricia Cornwell and the facility is named after Kay Scarpetta, Cornwell’s medical examiner heroine. Her books, including 24 novels in the Scarpetta series and 2 non-fiction books on Jack the Ripper, have sold more than 100 million copies worldwide.

It should come as no surprise that the Scarpetta house is incredibly accurate in every detail. Cigarettes on the kitchen table, cereal boxes on the counter, trash in the trashcans: it looks like someone just stepped out to get the mail. Bruce notes that a few years ago, the M.E.’s office used bloody mannequins to recreate death scene scenarios for investigators to solve, but now they use live volunteers to portray the dead.

“We have local makeup artists with ‘Special FX’ experience from TV and movies come in to apply the Moulage make-up. And they look very realistic. We’ve even had some celebrities come in to portray dead people. It’s like a bucket list thing with them.” Bruce continues, “Last year my brother came in and portrayed a suicide victim. His family asked him not to take the makeup off when he was finished so they could see it. I drove him home (in the passenger seat) with a gunshot wound (complete with dripping blood) to the right temple. I even pulled in to the 7-Eleven and parked. Nobody even raised an eyebrow. He warned me that if I got pulled over for speeding, he was gonna play dead and let me explain it.”

I must admit that by this time in our visit, the investigation bug had bitten our little group. The four of us were now spread out in the Scarpetta house in search of our own clues. And although the facility had been cleaned up after last Spring’s class departed, upon closer examination, blood spatter evidence remained in those hard to reach places found in normal household scenarios. For example, the space between the toilet & sink, the bathtub grout and that pesky space between the fridge and the cabinet. Rhonda notes that there was no toilet paper in the bathroom but the empty roll remained on the holder. “That is a crime in itself,” she states. While in the kitchen, Bruce pauses before saying, “Oh yeah, don’t open the fridge” before walking out of the room. Although tempted, we took his advice and left it alone without ever knowing exactly what was inside of it.

Viewing the Nutshell Studies in this information age of virtual reality, it becomes easy to appreciate them as works of art and popular culture over and above their importance as forensic tools. Lee’s hyper-real dioramas are designed to re-train people to see. It becomes obvious that Frances Glessner Lee’s genius for story telling by using simple materials was both exacting and highly creative in her pursuit of detail-knitting tiny stocking by hand with straight pins, writing minuscule letters with a single-hair paintbrush, and crafting working locks for tiny windows and doors. Exacting details, easily overlooked.

What may be most overlooked in her dioramas is the subtle social commentary found within these complex cases. Her subversive velvet touch challenges the mores of femininity, questions domestic bliss and upends the traditional ideals for dollhouse miniature modeling, sewing, and other crafts considered to be “women’s work” back in the day. Often, her models focus on society’s “invisible victims” and feature victims (women, the poor, and people living on the fringes of society) whose cases might be overlooked or tainted with prejudice on the part of the investigator. She wanted trainees to recognize and overcome any unconscious biases and to treat each case equally, regardless of the status of the victim.

So much of today’s culture is digital, and the Nutshell Studies are three-dimensional. You can’t really understand it from a flat page; you have to see it to believe it. And if that isn’t enough, Bruce Goldfarb is in the final stages of a book about Frances Glessner Lee. “Why not? I know her as well as anyone and it’s a story is worth telling. ” Bruce says. I’m sure that Bruce’s book will sum it up quite nicely…in a nutshell.

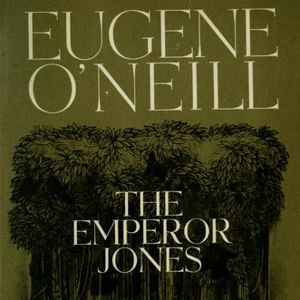

With the choice of O’Neill’s work, “The Emperor Jones”, the Society was taking an enormous risk if only for the fact that it required an elaborate stage for a one night performance. And then there was the Klan. The KKK was growing by leaps and bounds despite the fact that it had just been formally recognized in the state that same year. Soon, one third of the native male white born citizenry of the state would belong to the Klan. This was a play solely centered around a strong, murderous black man in a position of absolute authority in production in the principally white governed center of the WASP-ish Midwestern cornbelt.

With the choice of O’Neill’s work, “The Emperor Jones”, the Society was taking an enormous risk if only for the fact that it required an elaborate stage for a one night performance. And then there was the Klan. The KKK was growing by leaps and bounds despite the fact that it had just been formally recognized in the state that same year. Soon, one third of the native male white born citizenry of the state would belong to the Klan. This was a play solely centered around a strong, murderous black man in a position of absolute authority in production in the principally white governed center of the WASP-ish Midwestern cornbelt. W. F. McDermott, drama editor of the Indianapolis News, wrote this about Long: “a colored actor, played the role of the emperor with several moments of great naturalness. He was able to portray the negro fear of “ha’nts” with unusual power.” But McDermott was less kind to the playwrite, “O’Neill writes darkly of brooding, inscrutable fate; of black and stormbound heights, of man, stripped savage and terrified; of man tragically at odds with his environment and foredoomed.”

W. F. McDermott, drama editor of the Indianapolis News, wrote this about Long: “a colored actor, played the role of the emperor with several moments of great naturalness. He was able to portray the negro fear of “ha’nts” with unusual power.” But McDermott was less kind to the playwrite, “O’Neill writes darkly of brooding, inscrutable fate; of black and stormbound heights, of man, stripped savage and terrified; of man tragically at odds with his environment and foredoomed.” Perhaps the most unusual feature of the Indianapolis production was the choice of the lead actor chosen to portray Brutus Jones. Arthur Theodore Long was born on December 31, 1884, the son of Henry and Nattie (Buckner) Long in Morrillton, Arkansas. According to the 6th edition of “Who’s Who in Colored America (1941-1944)”, Long graduated from Sumner High School in St. Louis, Missouri in 1904. He entered the University of Illinois at age twenty and earned a BA degree in 1908. Arthur then went on to further his education at both Indiana and Butler universities. He then studied at the University of Chicago, presumably in pursuit of his master’s degree. Long earned teaching credentials in history, civics, English, music and mathematics.

Perhaps the most unusual feature of the Indianapolis production was the choice of the lead actor chosen to portray Brutus Jones. Arthur Theodore Long was born on December 31, 1884, the son of Henry and Nattie (Buckner) Long in Morrillton, Arkansas. According to the 6th edition of “Who’s Who in Colored America (1941-1944)”, Long graduated from Sumner High School in St. Louis, Missouri in 1904. He entered the University of Illinois at age twenty and earned a BA degree in 1908. Arthur then went on to further his education at both Indiana and Butler universities. He then studied at the University of Chicago, presumably in pursuit of his master’s degree. Long earned teaching credentials in history, civics, English, music and mathematics.

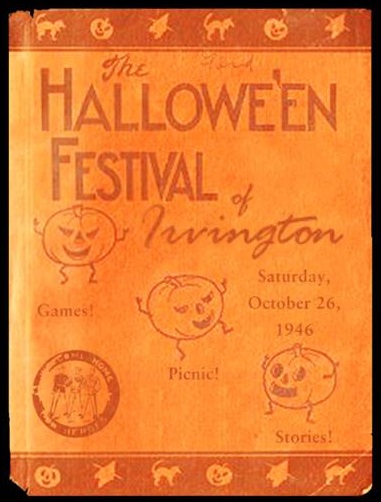

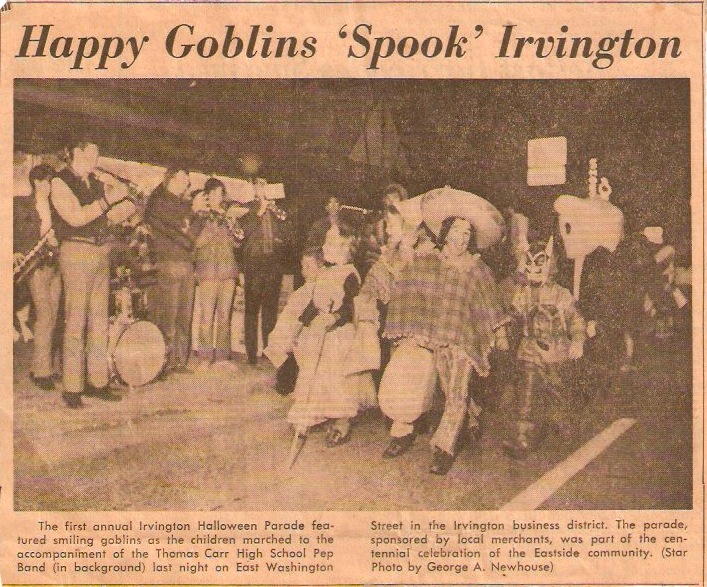

We’ve all heard the stories, legends and rumors surrounding that now legendary first event. It was sponsored by the Walt Disney company featuring costumed characters with a Disney based theme. The Disney folks gave away potentially priceless hand painted film production cels right here on the streets of old Irvington town. Walt Disney himself was seen walking down Audubon with Mickey Mouse at his side. It’s hard to separate fact from fiction nowadays.

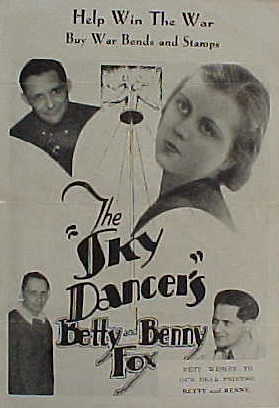

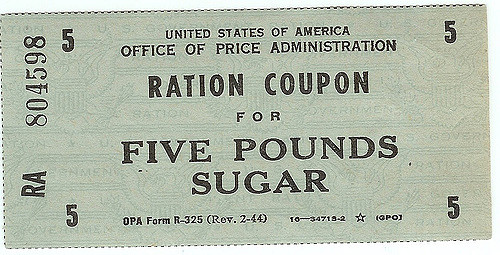

We’ve all heard the stories, legends and rumors surrounding that now legendary first event. It was sponsored by the Walt Disney company featuring costumed characters with a Disney based theme. The Disney folks gave away potentially priceless hand painted film production cels right here on the streets of old Irvington town. Walt Disney himself was seen walking down Audubon with Mickey Mouse at his side. It’s hard to separate fact from fiction nowadays. A week later on May 5, 1942, every United States citizen received their much anticipated “War Ration Book Number One”, good for a 56-week supply of sugar. Initially, each stamp was good for one pound of sugar and could be redeemed over a specified two-week period. Later on, as other items such as coffee and shoes were rationed, each stamp became good for two pounds of sugar over a four-week period. The ration book bore the recipient’s name and could only be used by household members. Stamps had to be torn off in the presence of the grocer. If the book was lost, stolen, or destroyed, an application had to be submitted to the Ration Board for a new copy. If the ration book holder entered the hospital for greater than a 10-day stay, the ration book had to be brought along with them. Talk about your red tape!

A week later on May 5, 1942, every United States citizen received their much anticipated “War Ration Book Number One”, good for a 56-week supply of sugar. Initially, each stamp was good for one pound of sugar and could be redeemed over a specified two-week period. Later on, as other items such as coffee and shoes were rationed, each stamp became good for two pounds of sugar over a four-week period. The ration book bore the recipient’s name and could only be used by household members. Stamps had to be torn off in the presence of the grocer. If the book was lost, stolen, or destroyed, an application had to be submitted to the Ration Board for a new copy. If the ration book holder entered the hospital for greater than a 10-day stay, the ration book had to be brought along with them. Talk about your red tape!

To make matters worse, just because you had a sugar stamp didn’t mean sugar was available for purchase. Shortages occurred often throughout the war, and in early 1945 sugar became nearly impossible to find in any quantity. As Europe was liberated from the grip of Nazi Germany, the United States took on the main responsibility for providing food to those war ravaged countries. On May 1, 1945, the sugar ration for American families was slashed to 15 pounds per year for household use and 15 pounds per year for canning – roughly eight ounces per week per household. Sugar supplies remained scarce and, just as sugar had the distinction of being the first product rationed at the start of the war, sugar was the last product to be rationed after the war. Sugar rationing continued until June of 1947, over six months after the first Irvington Halloween festival in October of 1946.

To make matters worse, just because you had a sugar stamp didn’t mean sugar was available for purchase. Shortages occurred often throughout the war, and in early 1945 sugar became nearly impossible to find in any quantity. As Europe was liberated from the grip of Nazi Germany, the United States took on the main responsibility for providing food to those war ravaged countries. On May 1, 1945, the sugar ration for American families was slashed to 15 pounds per year for household use and 15 pounds per year for canning – roughly eight ounces per week per household. Sugar supplies remained scarce and, just as sugar had the distinction of being the first product rationed at the start of the war, sugar was the last product to be rationed after the war. Sugar rationing continued until June of 1947, over six months after the first Irvington Halloween festival in October of 1946. An argument can be made that it was events like the First Irvington Halloween Festival that kicked off the tradition of trick-or-treating as we know it today. Although the Halloween holiday was certainly well known in America before that first Irvington celebration, it was predominantly a holiday for adult costume parties and a chance to cut loose with friends playing party games while consuming hard cider. Early national attention to trick-or-treating in popular culture really began a year later in October of 1947. That’s when the custom of passing out the playful “candy bribes” began to appear in issues of children’s magazines like Jack and Jill and Children’s Activities, and in Halloween episodes of network radio programs like The Baby Snooks Show, The Jack Benny Show and The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet. Trick-or-treating was first depicted in a Peanuts comic strip in 1951, perhaps the image most identified with the children’s holiday in the hearts and minds of baby boomers today. The custom had become firmly established in popular culture by 1952, when Walt Disney debuted his Donald Duck movie “Trick or Treat”, and again when Ozzie and Harriet were besieged by trick-or-treaters on an episode of their popular television show. In 1953, less than a decade after that first festival in Irvington, the tradition of Halloween as a children’s holiday was fully accepted when UNICEF conducted it’s first national children’s charity fund raising campaign centered around trick-or-treaters.

An argument can be made that it was events like the First Irvington Halloween Festival that kicked off the tradition of trick-or-treating as we know it today. Although the Halloween holiday was certainly well known in America before that first Irvington celebration, it was predominantly a holiday for adult costume parties and a chance to cut loose with friends playing party games while consuming hard cider. Early national attention to trick-or-treating in popular culture really began a year later in October of 1947. That’s when the custom of passing out the playful “candy bribes” began to appear in issues of children’s magazines like Jack and Jill and Children’s Activities, and in Halloween episodes of network radio programs like The Baby Snooks Show, The Jack Benny Show and The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet. Trick-or-treating was first depicted in a Peanuts comic strip in 1951, perhaps the image most identified with the children’s holiday in the hearts and minds of baby boomers today. The custom had become firmly established in popular culture by 1952, when Walt Disney debuted his Donald Duck movie “Trick or Treat”, and again when Ozzie and Harriet were besieged by trick-or-treaters on an episode of their popular television show. In 1953, less than a decade after that first festival in Irvington, the tradition of Halloween as a children’s holiday was fully accepted when UNICEF conducted it’s first national children’s charity fund raising campaign centered around trick-or-treaters. Most of this column’s readers are aware that part of my passion for history revolves around collecting, cataloging, displaying and observing antiques and collectibles. There exists in the collecting world a strong group of enthusiasts devoted to the pursuit and preservation of Halloween memorabilia of all types. Costumes, decorations, photographs, publications and postcards in particular. The origins of Halloween as we now know it might best be traced in the postcards issued to celebrate the tradition. The thousands of Halloween postcards produced between the turn of the 20th century and the 1920s commonly show costumed children, but do not depict trick-or-treating. It is believed that the pranks associated with early Halloween were perpetrated by unattended children left to their own devices while their parents caroused and partied without them. Some have characterized Halloween trick-or-treating as an adult invention to curtail vandalism previously associated with the holiday. Halloween was not widely accepted and many adults, as reported in newspapers from the 1930s and 1940s, typically saw it as a form of extortion, with reactions ranging from bemused indulgence to anger. Sometimes, even the children protested. As late as Halloween of 1948, members of the Madison Square Boys Club in New York City carried a parade banner that read “American Boys Don’t Beg.” Times have certainly changed since that first Halloween festival 65 years ago.

Most of this column’s readers are aware that part of my passion for history revolves around collecting, cataloging, displaying and observing antiques and collectibles. There exists in the collecting world a strong group of enthusiasts devoted to the pursuit and preservation of Halloween memorabilia of all types. Costumes, decorations, photographs, publications and postcards in particular. The origins of Halloween as we now know it might best be traced in the postcards issued to celebrate the tradition. The thousands of Halloween postcards produced between the turn of the 20th century and the 1920s commonly show costumed children, but do not depict trick-or-treating. It is believed that the pranks associated with early Halloween were perpetrated by unattended children left to their own devices while their parents caroused and partied without them. Some have characterized Halloween trick-or-treating as an adult invention to curtail vandalism previously associated with the holiday. Halloween was not widely accepted and many adults, as reported in newspapers from the 1930s and 1940s, typically saw it as a form of extortion, with reactions ranging from bemused indulgence to anger. Sometimes, even the children protested. As late as Halloween of 1948, members of the Madison Square Boys Club in New York City carried a parade banner that read “American Boys Don’t Beg.” Times have certainly changed since that first Halloween festival 65 years ago. A 2005 study by the National Confectioners Association reported that 80 percent of American households gave out candy to trick-or-treaters, and that 93 percent of children, teenagers, and young adults planned to either venture out trick-or-treating or to participate in other Halloween associated activities. In 2008, Halloween candy, costumes and other related products accounted for $5.77 billion in revenue. An estimated $2 billion worth of candy will be passed out during this Halloween season and one study claims that “an average Jack-O-Lantern bucket carries about 250 pieces of candy amounting to about 9,000 calories and containing three pounds of sugar.” Yes, 65-years ago, Halloween looked quite different than it does today. Next week, doorbells all over Irvington will ring, doors will be opened and wide-eyed gaggles of eager children will unanimously cry out “Trick-or-Treat” from Oak Avenue to Pleasant Run Parkway.

A 2005 study by the National Confectioners Association reported that 80 percent of American households gave out candy to trick-or-treaters, and that 93 percent of children, teenagers, and young adults planned to either venture out trick-or-treating or to participate in other Halloween associated activities. In 2008, Halloween candy, costumes and other related products accounted for $5.77 billion in revenue. An estimated $2 billion worth of candy will be passed out during this Halloween season and one study claims that “an average Jack-O-Lantern bucket carries about 250 pieces of candy amounting to about 9,000 calories and containing three pounds of sugar.” Yes, 65-years ago, Halloween looked quite different than it does today. Next week, doorbells all over Irvington will ring, doors will be opened and wide-eyed gaggles of eager children will unanimously cry out “Trick-or-Treat” from Oak Avenue to Pleasant Run Parkway. Costumed kids will be rewarded for their efforts with all sorts of tribute in the form of coins, nuts, popcorn balls, fruit, cookies, cakes, and toys. As a casual observer born long after that first Irvington Halloween Festival and an active participant in the festivities that will begin next week, I’m glad that our Irvington forefathers skirted government regulations all those years ago. In fact, as a fan of all things Irvington, I’d go so far as to say that this community has played a big part in the Halloween holiday as we know it today. Because, grammar notwithstanding, nobody does Halloween like Irvington do.

Costumed kids will be rewarded for their efforts with all sorts of tribute in the form of coins, nuts, popcorn balls, fruit, cookies, cakes, and toys. As a casual observer born long after that first Irvington Halloween Festival and an active participant in the festivities that will begin next week, I’m glad that our Irvington forefathers skirted government regulations all those years ago. In fact, as a fan of all things Irvington, I’d go so far as to say that this community has played a big part in the Halloween holiday as we know it today. Because, grammar notwithstanding, nobody does Halloween like Irvington do.

My first thought, where the heck is Bloomfield, Indiana? Well, if you didn’t know, it is a small town of some 2,400 people located in Greene County not far from, and currently considered a part of, Bloomington. Its best known for having one of the most well preserved covered bridges in the state and for its long association with the Native American Indian tribes including the Miami, Kickapoo, Piankeshaw, and Wesa tribes. That settled, I was on to the next question. What is this thing? I’m guessing some of you already know the answer, but it was unknown to me. It is a book, distributed by the electric company to their wartime, homefront customers to read their own meters and pay the fees associated with usage based on the honor system. That’s right, the honor system. With the electric company. An Oxymoron if you ever heard one right?

My first thought, where the heck is Bloomfield, Indiana? Well, if you didn’t know, it is a small town of some 2,400 people located in Greene County not far from, and currently considered a part of, Bloomington. Its best known for having one of the most well preserved covered bridges in the state and for its long association with the Native American Indian tribes including the Miami, Kickapoo, Piankeshaw, and Wesa tribes. That settled, I was on to the next question. What is this thing? I’m guessing some of you already know the answer, but it was unknown to me. It is a book, distributed by the electric company to their wartime, homefront customers to read their own meters and pay the fees associated with usage based on the honor system. That’s right, the honor system. With the electric company. An Oxymoron if you ever heard one right? The customer would record the electricity their household used, pay the bill, and the electric company trusted them. Seriously? The electric company…trust you? Could that be possible? Can you imagine such a system? I gotta tell ya, when I see things like this I’m convinced that I was born in the wrong era. I must admit, I’m one of those people that believes that the World War II Generation was truly our greatest. Life was simpler, people were nicer, and businesses were staffed by friends and neighbors who were really rooting for our success. Whenever I see things like this I realize that back then, everyone pulled together to do their part. All for one and one for all. Corny, but true. I didn’t realize that this little booklet was a first generation relic of the rural electrification movement that began in 1935 as part of an effort to bring electricity, telephone and indoor plumbing to the rural communities all over the state. Something we take for granted today.

The customer would record the electricity their household used, pay the bill, and the electric company trusted them. Seriously? The electric company…trust you? Could that be possible? Can you imagine such a system? I gotta tell ya, when I see things like this I’m convinced that I was born in the wrong era. I must admit, I’m one of those people that believes that the World War II Generation was truly our greatest. Life was simpler, people were nicer, and businesses were staffed by friends and neighbors who were really rooting for our success. Whenever I see things like this I realize that back then, everyone pulled together to do their part. All for one and one for all. Corny, but true. I didn’t realize that this little booklet was a first generation relic of the rural electrification movement that began in 1935 as part of an effort to bring electricity, telephone and indoor plumbing to the rural communities all over the state. Something we take for granted today.