https://weeklyview.net/2020/01/30/lewis-gardner-reynolds-carnation-day-abraham-lincoln-part-1/

Original publish date: January 30, 2020.

So what did you do last Wednesday? Did you place a red carnation on your lapel or buy a small arrangement for your table? Most likely, like most Americans, you did nothing remarkable at all. Our neighbors one state to the east probably joined you in your average humpday activities. Well, most of them anyway. Some were busy celebrating Carnation Day. What? You’ve never heard of that holiday? Well, don’t feel bad. You are not alone. Carnation Day was created to honor our country’s third assassinated President: Ohio’s favorite son, William McKinley. And, it was created by an Ohioan who lived and died in Richmond, Indiana. Most Americans remember President William McKinley solely for the way he died. His image a milquetoast chief executive from the age of American Imperialism who was at the helm for the dawn of the 20th century. McKinley’s ordinary appearance belied the fact that he was the last president to have served in the American Civil War and the only one to have started the war as an enlisted soldier. It is long forgotten that McKinley led the nation to victory in the Spanish-American War, protected American industry by raising tariffs, and kept the nation on the gold standard by rejecting free silver. Most notably, his assassination at the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York unleashed the central figure who would come to personify the new century; his Vice-President Teddy Roosevelt.

Most Americans remember President William McKinley solely for the way he died. His image a milquetoast chief executive from the age of American Imperialism who was at the helm for the dawn of the 20th century. McKinley’s ordinary appearance belied the fact that he was the last president to have served in the American Civil War and the only one to have started the war as an enlisted soldier. It is long forgotten that McKinley led the nation to victory in the Spanish-American War, protected American industry by raising tariffs, and kept the nation on the gold standard by rejecting free silver. Most notably, his assassination at the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York unleashed the central figure who would come to personify the new century; his Vice-President Teddy Roosevelt. McKinley’s favorite flower was a red carnation. He displayed his affection by wearing one of the bright red florets in his lapel every day. The carnation boutonnière soon became McKinley’s personal trademark. As President, bud vases filled with red carnations were conspicuously placed around the White House (known as the “Executive Mansion” back then). Whenever a guest visited the President, McKinley’s custom was to remove the carnation from his lapel and present it to the star-struck visitor. For men, he would often place the souvenir blossom into the lapel himself and suggest that it be given to an absent wife, mother, or child. Afterward, he would replace his boutonnière with another from a nearby vase and repeat the transfer again and again for the rest of the day. McKinley was superstitious about these carnations, believing that they brought good luck to both him and his recipient.

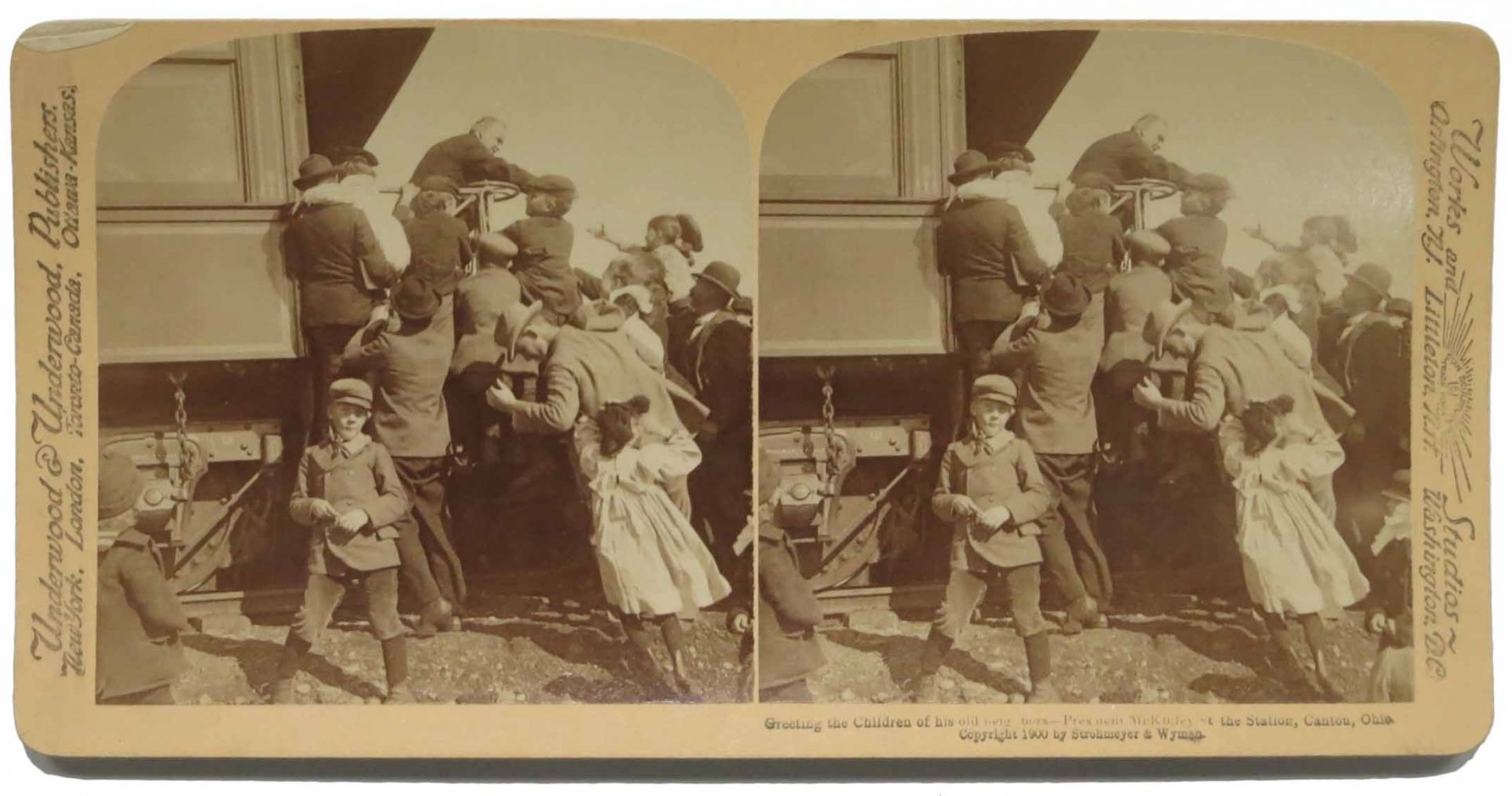

McKinley’s favorite flower was a red carnation. He displayed his affection by wearing one of the bright red florets in his lapel every day. The carnation boutonnière soon became McKinley’s personal trademark. As President, bud vases filled with red carnations were conspicuously placed around the White House (known as the “Executive Mansion” back then). Whenever a guest visited the President, McKinley’s custom was to remove the carnation from his lapel and present it to the star-struck visitor. For men, he would often place the souvenir blossom into the lapel himself and suggest that it be given to an absent wife, mother, or child. Afterward, he would replace his boutonnière with another from a nearby vase and repeat the transfer again and again for the rest of the day. McKinley was superstitious about these carnations, believing that they brought good luck to both him and his recipient. One account alleges that McKinley’s “Genus Dianthus” custom began early in his presidency when an aide brought his two sons to the White House to meet the President. McKinley, who loved children dearly, presented his carnation to the older boy. Seeing the disappointment in the younger boy’s face, the President deftly retrieved a replacement carnation and pinned it on his own lapel. Here the flower remained for a few moments before he removed it and gave to the younger child, explaining “this way you both can have a carnation worn by the President.”

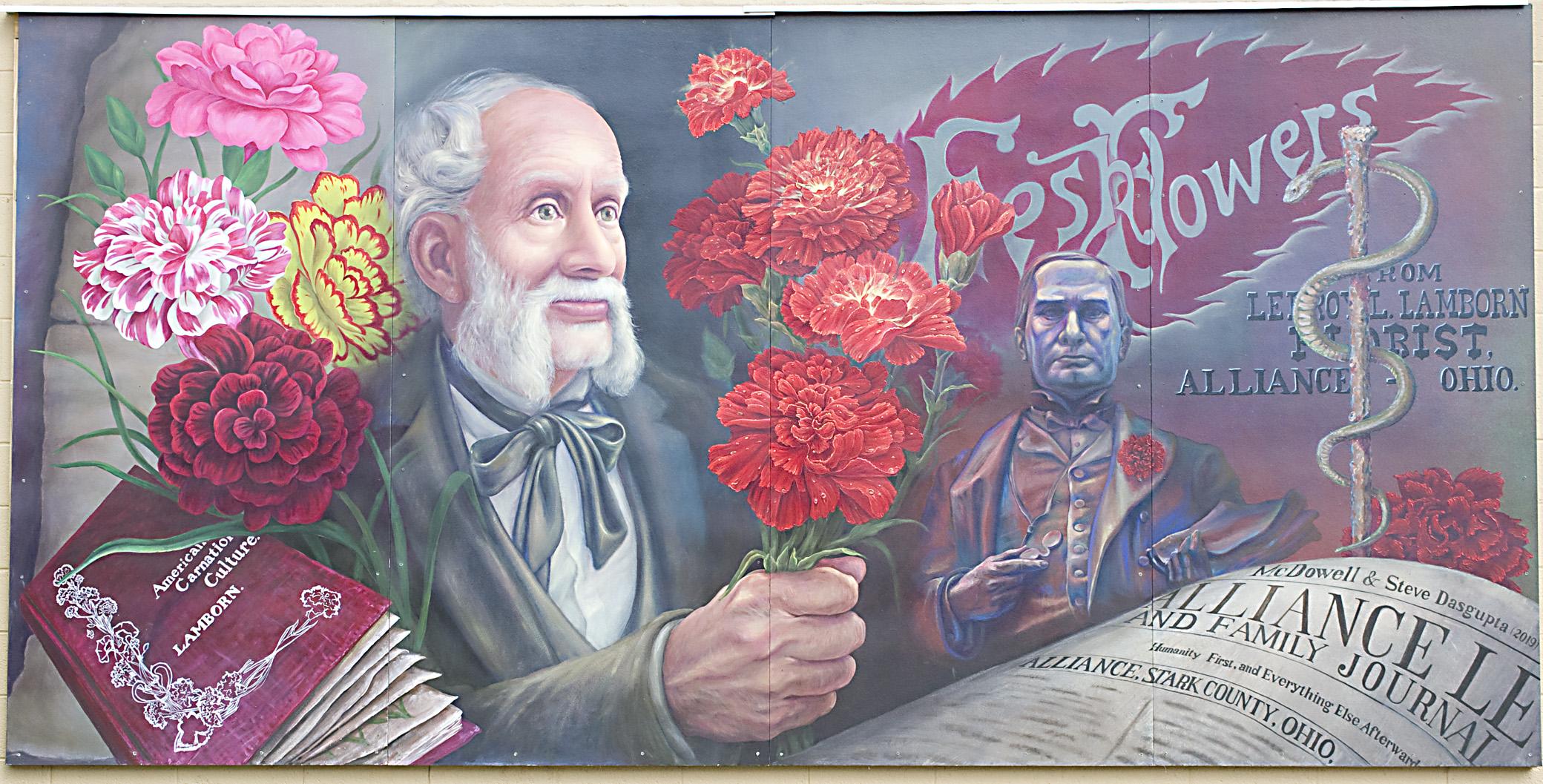

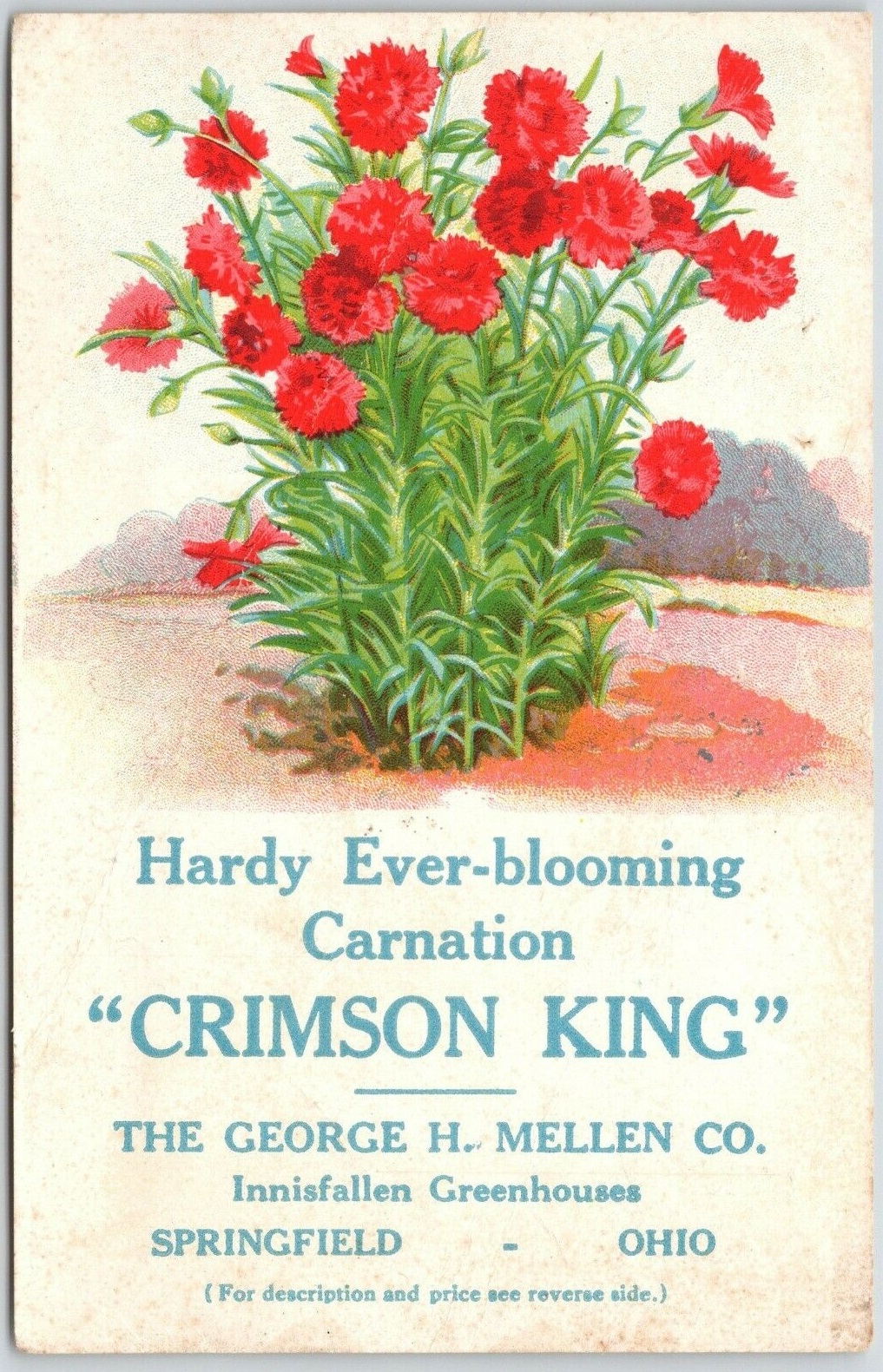

One account alleges that McKinley’s “Genus Dianthus” custom began early in his presidency when an aide brought his two sons to the White House to meet the President. McKinley, who loved children dearly, presented his carnation to the older boy. Seeing the disappointment in the younger boy’s face, the President deftly retrieved a replacement carnation and pinned it on his own lapel. Here the flower remained for a few moments before he removed it and gave to the younger child, explaining “this way you both can have a carnation worn by the President.” However, McKinley’s ubiquitous floral tradition can be traced to the election of 1876, when he was running for a seat in Congress. His opponent, Dr. Levi Lamborn, of Alliance, Ohio, was an accomplished amateur horticulturist famed for developing a strain of vivid scarlet carnations he dubbed “Lamborn Red.” Dr. Lamborn presented McKinley with a “Lamborn Red” boutonniere before their debates. After he won the election, McKinley viewed the red carnation as a good luck charm. He wore one on his lapel regularly and soon began his custom of presenting them to visitors. He wore one during his fourteen years in Congress, his two gubernatorial wins and both 1896 and 1900 presidential campaigns.

However, McKinley’s ubiquitous floral tradition can be traced to the election of 1876, when he was running for a seat in Congress. His opponent, Dr. Levi Lamborn, of Alliance, Ohio, was an accomplished amateur horticulturist famed for developing a strain of vivid scarlet carnations he dubbed “Lamborn Red.” Dr. Lamborn presented McKinley with a “Lamborn Red” boutonniere before their debates. After he won the election, McKinley viewed the red carnation as a good luck charm. He wore one on his lapel regularly and soon began his custom of presenting them to visitors. He wore one during his fourteen years in Congress, his two gubernatorial wins and both 1896 and 1900 presidential campaigns.

Years later, Dr. L.L. Lamborn recalled, “We differed politically but were personal friends. Fate decreed that we looked at political questions through different party prisms. We canvassed the district together and jointly discussed the issues of that campaign.

The contest was fervent but friendly. I was then raising the first carnations grown in the West. In our contests on the political forum, McKinley always wore carnation boutonnieres which were willingly furnished from my conservatory. I have a distinct recollection of him expressing his admiration for the flower. It was doubtless at that time he formed a preferential love for the divine flower. That love increased with his years and honors of his famous life. Through it he offered his affections to the beautiful and the true.”

Ohio Senator Mark Hannah recalled, “Oftentimes the President would wear 100 flowers in one day. Mr. McKinley always appeared at the executive office in the morning with a carnation in his buttonhole, and when it became necessary to turn down a candidate for office who had succeeded in obtaining a personal interview he frequently took the flower from his own buttonhole and pinned it on the coat of the office seeker. It was generally understood by the officials in the outer rooms that when a candidate came from the President’s office thus decorated the carnation was all he got.” After his second inauguration on March 4, 1901, William and Ida McKinley departed on a six-week train trip of the country. The McKinleys were to travel through the South to the Southwest, and then up the Pacific coast and back east again, to conclude with a visit to the Buffalo Exposition on June 13, 1901. However, the First Lady fell ill in California, causing her husband to limit his public events and cancel a series of planned speeches. The First family retreated to Washington for a month and then traveled to their Canton, Ohio home for another two months, delaying the Expo trip until September.

After his second inauguration on March 4, 1901, William and Ida McKinley departed on a six-week train trip of the country. The McKinleys were to travel through the South to the Southwest, and then up the Pacific coast and back east again, to conclude with a visit to the Buffalo Exposition on June 13, 1901. However, the First Lady fell ill in California, causing her husband to limit his public events and cancel a series of planned speeches. The First family retreated to Washington for a month and then traveled to their Canton, Ohio home for another two months, delaying the Expo trip until September.

On September 5, the President, wearing his trademark red carnation, delivered a speech to a crowd of some 50,000 people at the Exposition. One man in the crowd, Leon Czolgosz (pronounced “zoll-goss”), was close enough to the President that he could almost smell the fragrant blossom. Czolgosz, a steelworker and anarchist from Alpena, Michigan, hoped to assassinate McKinley. Although close to the presidential podium, unsure that he could hit his target, he did not fire. Instead, Czolgosz waited for the next day at the Temple of Music, where the President was scheduled to appear for a one-hour meet-and-greet with the general public.

The President stood at the head of the receiving line, pleasantly shaking hands with visitors, and wearing his ever-present lapel flower. A little 12-year-old girl named Myrtle Ledger, standing in line with her mother, asked the President, “Could I have something to show my friends?” True to form, McKinley removed the red carnation, bent down, and handed it to the child. Years later, Myrtle recalled that McKinley said, “In that case, I must give this flower to another little flower,” as he gave over his personal good luck charm.

However, this time McKinley was not in his familiar surroundings and had no replacement flower at hand. Ida, who usually sat in a chair next to the President armed with a basket full of carnations during such events, though in Buffalo, was not present at the event. Meanwhile, Leon Czolgosz edged closer to the President, his handkerchief-wrapped hand concealing a .32-caliber Iver Johnson “Safety Automatic” revolver. At 4:07 P.M., the President smiled broadly and extended his hand to greet the next person in line. Czolgosz slapped it aside and shot the President twice, at point-blank range: the first bullet ricocheted off a coat button and lodged in McKinley’s jacket; the other, seriously wounding the carnation-less President in the abdomen. As McKinley fell backwards into the arms of his aides, members of the crowd immediately attacked Czolgosz. McKinley said, “Go easy on him, boys.” McKinley urged his aides to break the news gently to Ida, and to call off the mob that had set on Czolgosz, thereby saving his assassin’s life. McKinley was taken to the Exposition aid station, where the doctor was unable to locate the second bullet. Ironically, although a newly developed X-ray machine was displayed at the fair, doctors were reluctant to use it on the President because they did not know what side effects. Worse yet, the operating room at the exposition’s emergency hospital did not have any electric lighting, even though the exteriors of many of the buildings were covered with thousands of light bulbs. Amazingly, doctors used a pan to reflect sunlight onto the operating table as they treated McKinley’s wounds.

As McKinley fell backwards into the arms of his aides, members of the crowd immediately attacked Czolgosz. McKinley said, “Go easy on him, boys.” McKinley urged his aides to break the news gently to Ida, and to call off the mob that had set on Czolgosz, thereby saving his assassin’s life. McKinley was taken to the Exposition aid station, where the doctor was unable to locate the second bullet. Ironically, although a newly developed X-ray machine was displayed at the fair, doctors were reluctant to use it on the President because they did not know what side effects. Worse yet, the operating room at the exposition’s emergency hospital did not have any electric lighting, even though the exteriors of many of the buildings were covered with thousands of light bulbs. Amazingly, doctors used a pan to reflect sunlight onto the operating table as they treated McKinley’s wounds.

In the days after the shooting McKinley appeared to improve and newspapers were full of optimistic reports. Eight days after the shooting, on the morning of September 13, McKinley’s condition deteriorated and by afternoon physicians declared the case hopeless. It would later be determined that the gangrene was growing on the walls of his stomach, slowly poisoning his blood. McKinley drifted in and out of consciousness all day. By evening, McKinley himself knew he was dying, “It is useless, gentlemen. I think we ought to have prayer.” Relatives and friends gathered around the deathbed. The First Lady sobbed over him, “I want to go, too. I want to go, too.” Her husband replied, “We are all going, we are all going. God’s will be done, not ours” and with final strength put an arm around her. Some reports claimed that he also sang part of his favorite hymn, “Nearer, My God, to Thee” while others claim that the First Lady sang it softly to him. At 2:15 a.m. on September 14, President McKinley died. Czolgosz was sentenced to death and executed by electric chair on October 29, 1901.

McKinley drifted in and out of consciousness all day. By evening, McKinley himself knew he was dying, “It is useless, gentlemen. I think we ought to have prayer.” Relatives and friends gathered around the deathbed. The First Lady sobbed over him, “I want to go, too. I want to go, too.” Her husband replied, “We are all going, we are all going. God’s will be done, not ours” and with final strength put an arm around her. Some reports claimed that he also sang part of his favorite hymn, “Nearer, My God, to Thee” while others claim that the First Lady sang it softly to him. At 2:15 a.m. on September 14, President McKinley died. Czolgosz was sentenced to death and executed by electric chair on October 29, 1901.

The light had gone out of Ida McKinley’s life. She could not even bring herself to attend his funeral. Ida & William McKinley’s relationship has always been a marvel to me. She was an epileptic whose husband took great care to accommodate her condition. Contrary to protocol, he insisted that his wife be seated next to him at state dinners rather than her traditional position at the opposite end of the table. Guests noted that whenever Mrs. McKinley encountered a seizure, the President would gently place a napkin or handkerchief over her face to conceal her contorted features. When it passed, he removed it and resumed whatever he was doing as if nothing had happened. A story of true devotion that is rarely remarked on by modern day historians. Ida’s health declined as she withdrew to the safety of her home and happier memories in Canton. She survived her husband by less than six years, dying on May 26, 1907 and is buried next to him and their two daughters in Canton’s McKinley Memorial Mausoleum. Loyal readers will recognize my affinity for objects and will not be surprised by the query, “What became of that assassination carnation?” In an article for the Massillon, Ohio Daily Independent newspaper on Sept. 7, 1984, Myrtle Ledger Krass, the 12-year-old-girl to whom the President gave his lucky flower moments before he was killed, reported that the McKinley’s carnation was pressed and kept in the family Bible. Myrtle, at the time a well-known painter living in Largo, Florida, explained how, many years later while moving, “The old Bible had been put away for years, when I took it out to wrap it for moving, it just crumbled in my hand. Just fell away to nothing.”

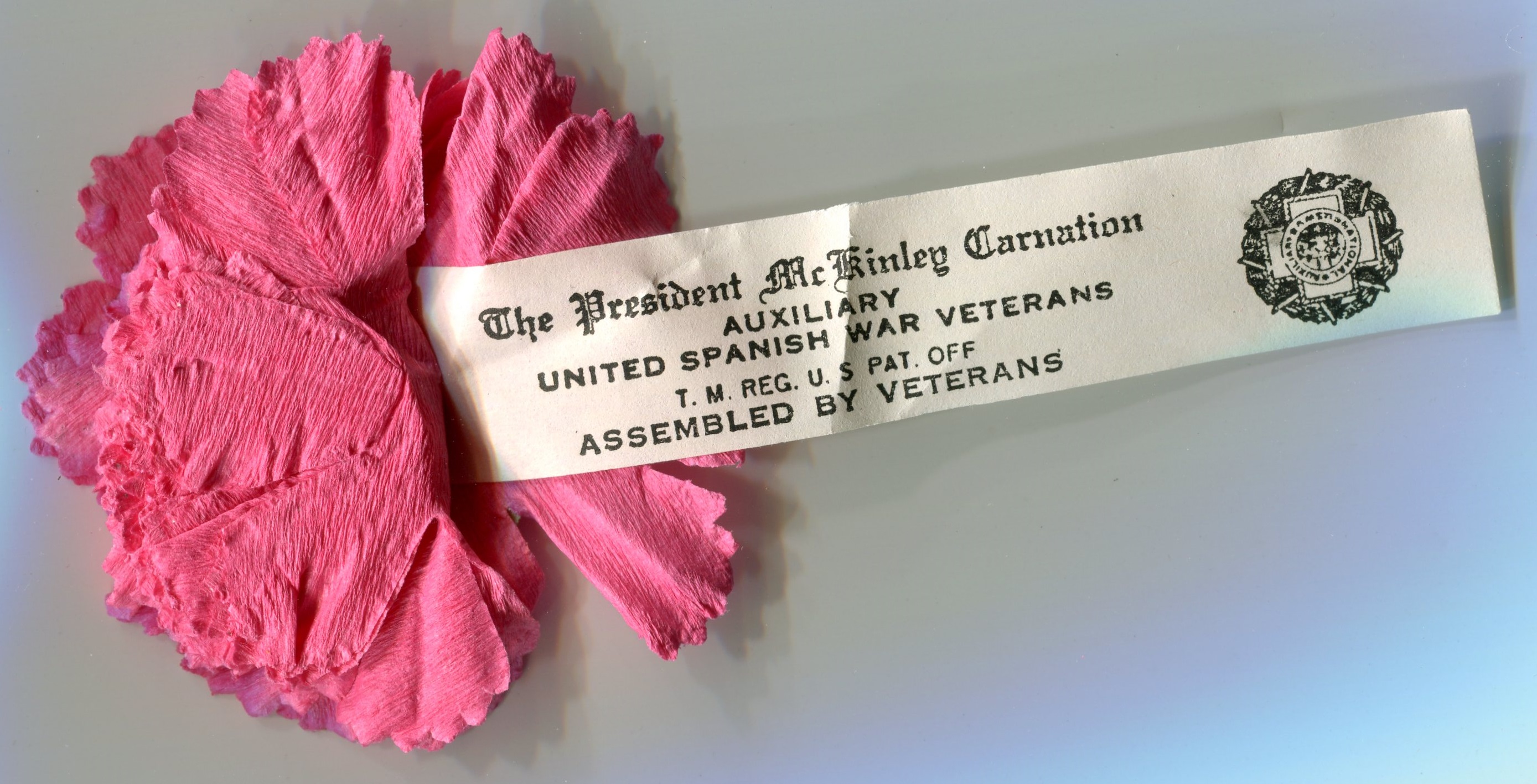

Loyal readers will recognize my affinity for objects and will not be surprised by the query, “What became of that assassination carnation?” In an article for the Massillon, Ohio Daily Independent newspaper on Sept. 7, 1984, Myrtle Ledger Krass, the 12-year-old-girl to whom the President gave his lucky flower moments before he was killed, reported that the McKinley’s carnation was pressed and kept in the family Bible. Myrtle, at the time a well-known painter living in Largo, Florida, explained how, many years later while moving, “The old Bible had been put away for years, when I took it out to wrap it for moving, it just crumbled in my hand. Just fell away to nothing.” In 1902, Lewis Gardner Reynolds (born in 1858 in Bellefontaine, Ohio) found himself in Buffalo on business on the first anniversary of McKinley’s death. While there he found that the mayor of Buffalo had declared the day a legal holiday. Gardner recalled, “without thinking at the time that I was doing something that would become a national custom, I purchased a pink carnation which I placed in the buttonhole of my coat after tying a small piece of black ribbon on it. As I went through Buffalo I explained to questioners the reason for the flower and the black ribbon. Many of those who questioned me followed my example.” On his return to Ohio, he explained to his friend Senator Mark Hannah what he had done in Buffalo. Later, in Cleveland, Reynolds met with Hannah and Governor Myron T. Herrick. Soon plans were made to celebrate Jan. 29, the anniversary of McKinley’s birth, as “Carnation Day.”

In 1902, Lewis Gardner Reynolds (born in 1858 in Bellefontaine, Ohio) found himself in Buffalo on business on the first anniversary of McKinley’s death. While there he found that the mayor of Buffalo had declared the day a legal holiday. Gardner recalled, “without thinking at the time that I was doing something that would become a national custom, I purchased a pink carnation which I placed in the buttonhole of my coat after tying a small piece of black ribbon on it. As I went through Buffalo I explained to questioners the reason for the flower and the black ribbon. Many of those who questioned me followed my example.” On his return to Ohio, he explained to his friend Senator Mark Hannah what he had done in Buffalo. Later, in Cleveland, Reynolds met with Hannah and Governor Myron T. Herrick. Soon plans were made to celebrate Jan. 29, the anniversary of McKinley’s birth, as “Carnation Day.”

In 1903, Reynolds founded the Carnation League of America and instituted Red Carnation Day as an annual memorial to McKinley. Standing for patriotism, progress, prosperity, and peace, the League encouraged all Americans to wear a red carnation on McKinley’s birthday. Not only did the new holiday honor the martyr’s birthday, but it also encouraged people to patronize florists. In Dayton alone that year, more than 15,000 carnations were sold on McKinley’s birthday. On February 3, 1904, to honor McKinley, the Ohio General Assembly declared the scarlet carnation the state flower. After the U.S. entered World War I, people started wearing an American flag instead of a carnation on January 29. In 1918, Red Carnation Day celebrations began declining and eventually stopped altogether. Today, the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus continues observing Red Carnation Day every January 29 by installing a small display honoring the assassinated President. Last year, the Statehouse Museum Shop and on-site restaurant offered special discounts to anyone wearing a red carnation or dressed in scarlet on that day. Yes, the sentimental association of the carnation with McKinley’s memory is due to Lewis Gardner Reynolds.

Today, the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus continues observing Red Carnation Day every January 29 by installing a small display honoring the assassinated President. Last year, the Statehouse Museum Shop and on-site restaurant offered special discounts to anyone wearing a red carnation or dressed in scarlet on that day. Yes, the sentimental association of the carnation with McKinley’s memory is due to Lewis Gardner Reynolds.

However, that is not the only claim to fame to be made for Mr. Reynolds. He would meet and fall in love with a girl from Richmond and, after moving there, he would spearhead the Teddy Roosevelt Memorial effort and post-World War I European Relief Commission efforts in Wayne County. He would travel to Washington DC and take over curatorship of the Lincoln collection after its owner Osborn Oldroyd sold it to the US Government in 1926. He would supervise the collection’s move across the street to Ford’s Theatre, where it remains today. And, he would survive to the dawn of World War to stake his claim as the last living person to have met Abraham Lincoln.

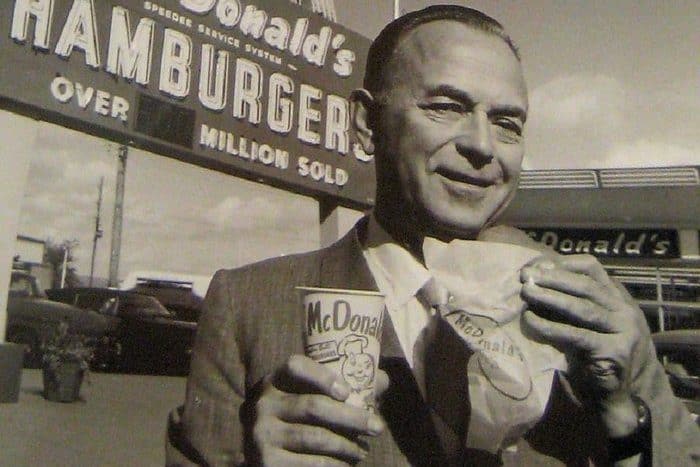

By this time, Ray Kroc was relegated to the sidelines serving in a largely ceremonial role as McDonald’s “senior chairman”. Kroc had given up day-to-day operations of McDonald’s in 1974. Ironically, the same year he bought the San Diego Padres baseball team. The Padres were scheduled to move to Washington, D.C., after the 1973 season. Legend claims that the idea to buy the team formulated in Kroc’s mind while he was reading a newspaper on his private jet. Kroc, a life-long baseball fan who was once foiled in an attempt to buy his hometown Chicago Cubs, turned to his wife Joan and said: “I think I want to buy the San Diego Padres.” Her response: “Why would you want to buy a monastery?” Five years later, frustrated with the team’s performance and league restrictions, Kroc turned the team over to his son-in-law, Ballard Smith. “There’s more future in hamburgers than baseball,” Kroc said. Ray Kroc died on January 14, 1984 and the San Diego Padres won the N.L. pennant that same year (They lost in the World Series to the Detroit Tiger 4 games to 1).

By this time, Ray Kroc was relegated to the sidelines serving in a largely ceremonial role as McDonald’s “senior chairman”. Kroc had given up day-to-day operations of McDonald’s in 1974. Ironically, the same year he bought the San Diego Padres baseball team. The Padres were scheduled to move to Washington, D.C., after the 1973 season. Legend claims that the idea to buy the team formulated in Kroc’s mind while he was reading a newspaper on his private jet. Kroc, a life-long baseball fan who was once foiled in an attempt to buy his hometown Chicago Cubs, turned to his wife Joan and said: “I think I want to buy the San Diego Padres.” Her response: “Why would you want to buy a monastery?” Five years later, frustrated with the team’s performance and league restrictions, Kroc turned the team over to his son-in-law, Ballard Smith. “There’s more future in hamburgers than baseball,” Kroc said. Ray Kroc died on January 14, 1984 and the San Diego Padres won the N.L. pennant that same year (They lost in the World Series to the Detroit Tiger 4 games to 1). By the 1980s, Disney was a corporation that seemed to be creatively exhausted. The entertainment giant was seriously out of touch with what consumers wanted to buy, what moviegoers wanted to see. McDonald’s had introduced their wildly popular “Happy Meal” nationwide in 1979. Disney saw an opportunity for revival by proposing the idea of adding Disney toys and merchandising to Happy Meals. In 1987, the first Disney Happy Meal debuted, offering toys and prizes from familiar characters like Cinderella, The Sword In The Stone, Mickey Mouse, Aladdin, Simba, Finding Nemo, Jungle Book, 101 Dalmatians, The Lion King and other classics. For a time, changing food habits, mismanagement and failure to recognize trends, placed the Disney corporation in an exposed position. Rumors circulated that the Mouse was on the brink of being swallowed up by Mickey D’s.

By the 1980s, Disney was a corporation that seemed to be creatively exhausted. The entertainment giant was seriously out of touch with what consumers wanted to buy, what moviegoers wanted to see. McDonald’s had introduced their wildly popular “Happy Meal” nationwide in 1979. Disney saw an opportunity for revival by proposing the idea of adding Disney toys and merchandising to Happy Meals. In 1987, the first Disney Happy Meal debuted, offering toys and prizes from familiar characters like Cinderella, The Sword In The Stone, Mickey Mouse, Aladdin, Simba, Finding Nemo, Jungle Book, 101 Dalmatians, The Lion King and other classics. For a time, changing food habits, mismanagement and failure to recognize trends, placed the Disney corporation in an exposed position. Rumors circulated that the Mouse was on the brink of being swallowed up by Mickey D’s.

Additionally, there once was a McDonald’s at downtown Disney (before it became Disney Springs). At the Magic Kingdom, visitors could munch on french fries at the Village Fire Shoppe. At Disney’s Hollywood Studios, McDonald’s sponsored Fairfax Fries at the Sunset Ranch March. Fairfax is a reference to the street where the famous Los Angeles Farmers Market (the inspiration for the Sunset Ranch Market) is located. At Epcot, on the World Showcase promenade, is the Refreshment Port where sometimes international cast members from Canada would bring Canadian Smarties (similar to M&Ms) for the food and beverage location to make a Smarties McFlurry. The exclusive contract with Disney did not allow McDonald’s to tie in with blockbuster movies such as the Star Wars franchise even though movie studios would have preferred the tie in since McDonald’s had a higher profile and market share.

Additionally, there once was a McDonald’s at downtown Disney (before it became Disney Springs). At the Magic Kingdom, visitors could munch on french fries at the Village Fire Shoppe. At Disney’s Hollywood Studios, McDonald’s sponsored Fairfax Fries at the Sunset Ranch March. Fairfax is a reference to the street where the famous Los Angeles Farmers Market (the inspiration for the Sunset Ranch Market) is located. At Epcot, on the World Showcase promenade, is the Refreshment Port where sometimes international cast members from Canada would bring Canadian Smarties (similar to M&Ms) for the food and beverage location to make a Smarties McFlurry. The exclusive contract with Disney did not allow McDonald’s to tie in with blockbuster movies such as the Star Wars franchise even though movie studios would have preferred the tie in since McDonald’s had a higher profile and market share.

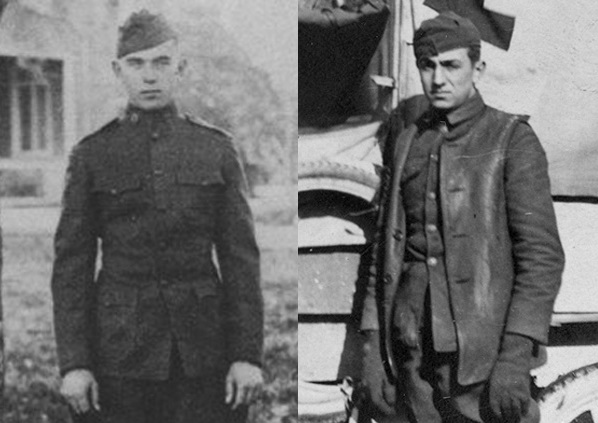

During his lifetime, Walt Disney received 59 Academy Award nominations, including 22 awards: both totals are records. Walt Disney’s net worth was equal to roughly $1 billion at the time of his death in 1966 (after adjusting for inflation). At the time of his death, Disney’s various assets were worth $100-$150 million in 1966 dollars which is the same as $750 million-$1.1 billion today. By the time of Kroc’s death in 1984, his net worth was $600 million. That’s the same as $1.4 billion after adjusting for inflation. One can only imagine how the pop culture landscape might have changed back in 1955 if those two former ambulance corps buddies had formed a partnership. But wait, would that make it Mickey D’s Mouse?

During his lifetime, Walt Disney received 59 Academy Award nominations, including 22 awards: both totals are records. Walt Disney’s net worth was equal to roughly $1 billion at the time of his death in 1966 (after adjusting for inflation). At the time of his death, Disney’s various assets were worth $100-$150 million in 1966 dollars which is the same as $750 million-$1.1 billion today. By the time of Kroc’s death in 1984, his net worth was $600 million. That’s the same as $1.4 billion after adjusting for inflation. One can only imagine how the pop culture landscape might have changed back in 1955 if those two former ambulance corps buddies had formed a partnership. But wait, would that make it Mickey D’s Mouse?

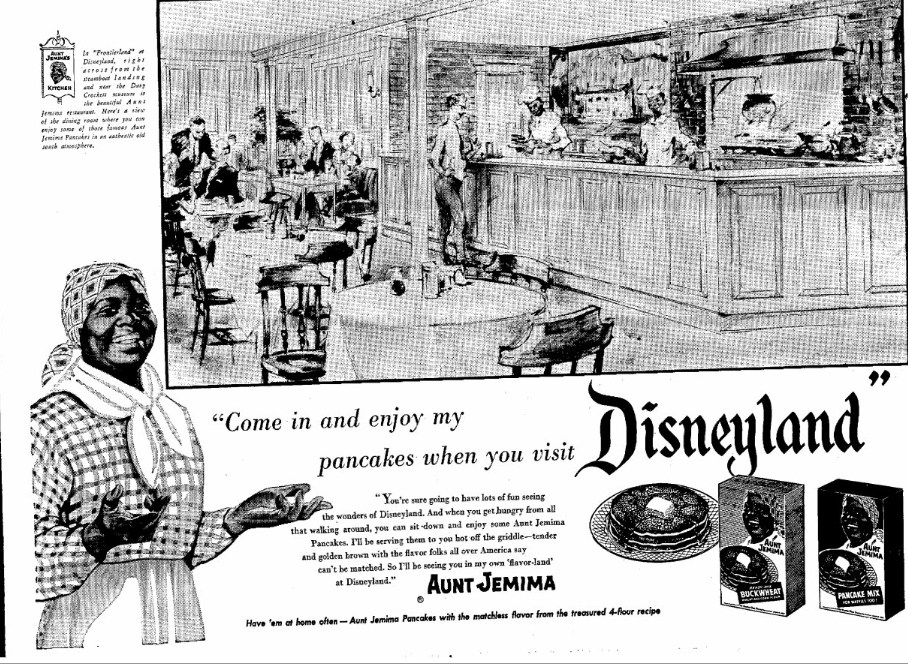

From there, well, nobody knows. For the answer, you need look no further than the fact that there are no McDonald’s at Disney. It should be noted that there were SOME franchise restaurants in Disneyland during those first first years. They included the Aunt Jemima pancake and waffle house in Frontierland and the Chicken of the Sea Pirate Ship in Fantasyland.

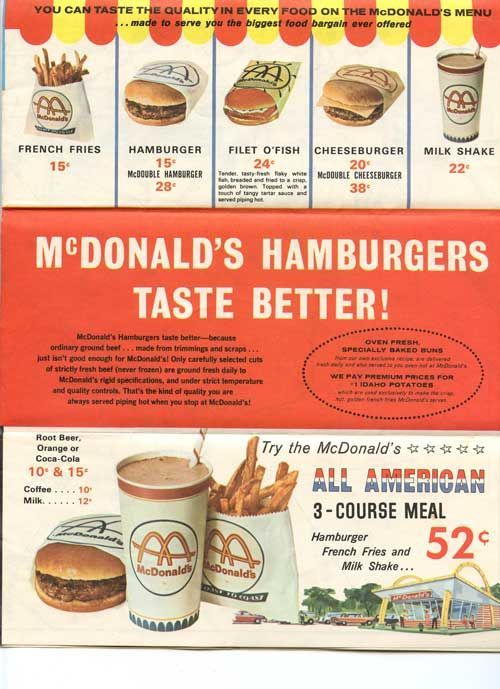

From there, well, nobody knows. For the answer, you need look no further than the fact that there are no McDonald’s at Disney. It should be noted that there were SOME franchise restaurants in Disneyland during those first first years. They included the Aunt Jemima pancake and waffle house in Frontierland and the Chicken of the Sea Pirate Ship in Fantasyland. To his dying day, Ray Kroc insisted that the reason the “world’s first McDonald’s” was not featured inside Disneyland at the park’s July 17, 1955 grand opening was because the head of concessions had tried to force Ray to raise the price of his french fries by a nickle (from 10 cents to 15 cents) for the Disneyland crowd. Kroc, the man in charge of McDonald’s franchising, believed that he was being charged a franchise fee by virtue of Walt Disney Productions tacking on a concessionaire’s fee. Kroc, the consummate businessman, said he wasn’t about to give away 1/3 of his profits while gouging his customers. Great story, but by the time Disneyland debuted, Kroc had only opened one McDonald’s franchise (in Des Plaines, Illinois on April 15, 1955). So he had no loyal customers to offend…yet. Well, no customers within 2,000 miles anyway.

To his dying day, Ray Kroc insisted that the reason the “world’s first McDonald’s” was not featured inside Disneyland at the park’s July 17, 1955 grand opening was because the head of concessions had tried to force Ray to raise the price of his french fries by a nickle (from 10 cents to 15 cents) for the Disneyland crowd. Kroc, the man in charge of McDonald’s franchising, believed that he was being charged a franchise fee by virtue of Walt Disney Productions tacking on a concessionaire’s fee. Kroc, the consummate businessman, said he wasn’t about to give away 1/3 of his profits while gouging his customers. Great story, but by the time Disneyland debuted, Kroc had only opened one McDonald’s franchise (in Des Plaines, Illinois on April 15, 1955). So he had no loyal customers to offend…yet. Well, no customers within 2,000 miles anyway. It is more likely to say that while the executives in charge of Disneyland’s concessions were undoubtedly intrigued by Ray’s “fast food” proposal, “war buddy” or not, Kroc just didn’t have enough experience in the restaurant business to take that gamble. So, despite how Kroc spun the tale to reporters from the 1950s forward, while there was some discussion of putting a McDonald’s inside the theme park, the project never really made it past the talking stage. But Ray Kroc would never let the truth stand in the way of a good story.

It is more likely to say that while the executives in charge of Disneyland’s concessions were undoubtedly intrigued by Ray’s “fast food” proposal, “war buddy” or not, Kroc just didn’t have enough experience in the restaurant business to take that gamble. So, despite how Kroc spun the tale to reporters from the 1950s forward, while there was some discussion of putting a McDonald’s inside the theme park, the project never really made it past the talking stage. But Ray Kroc would never let the truth stand in the way of a good story.

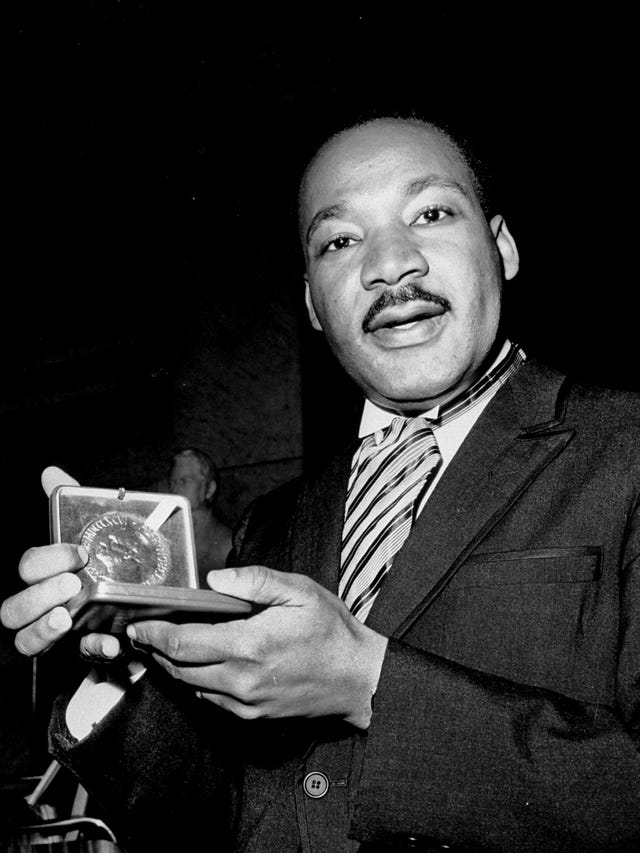

In 1970, two years after King’s assassination, Hoover told a Time reporter. “King was very suave and smooth. He sat right there where you’re sitting and said he never criticized the FBI. I said, ‘Mr. King’-I never called him reverend- ‘stop right there. You’re lying….If you ever say anything that’s a lie again, I’ll brand you a liar again.’ Strange to say, he never attacked the Bureau again for as long as he lived.” Nobody else present that day remembered that confrontation-not Young, not Abernathy, not even Deputy Director Deke DeLoach, who was taking notes that afternoon.

In 1970, two years after King’s assassination, Hoover told a Time reporter. “King was very suave and smooth. He sat right there where you’re sitting and said he never criticized the FBI. I said, ‘Mr. King’-I never called him reverend- ‘stop right there. You’re lying….If you ever say anything that’s a lie again, I’ll brand you a liar again.’ Strange to say, he never attacked the Bureau again for as long as he lived.” Nobody else present that day remembered that confrontation-not Young, not Abernathy, not even Deputy Director Deke DeLoach, who was taking notes that afternoon.

Even though I was very young, I can remember that in May of 1968, Hollywood came to town to film a major movie at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Although I didn’t know it at the time, the film was called “Winning,” and starred Paul Newman and his real-life wife, Joanne Woodward. The plot focused on an ambitious race driver determined to win the Indianapolis 500 in an effort to resurrect his flagging career. The film also starred Richard Thomas, soon to become more famous as “John Boy” on “The Waltons” TV series and Robert Wagner (of “Hart to Hart” TV fame). Several real-life racing figures-including the Speedway’s owner, Tony Hulman, and race driver Bobby Unser-portray themselves in the movie.

Even though I was very young, I can remember that in May of 1968, Hollywood came to town to film a major movie at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Although I didn’t know it at the time, the film was called “Winning,” and starred Paul Newman and his real-life wife, Joanne Woodward. The plot focused on an ambitious race driver determined to win the Indianapolis 500 in an effort to resurrect his flagging career. The film also starred Richard Thomas, soon to become more famous as “John Boy” on “The Waltons” TV series and Robert Wagner (of “Hart to Hart” TV fame). Several real-life racing figures-including the Speedway’s owner, Tony Hulman, and race driver Bobby Unser-portray themselves in the movie.