Original publish date: March 5, 2020

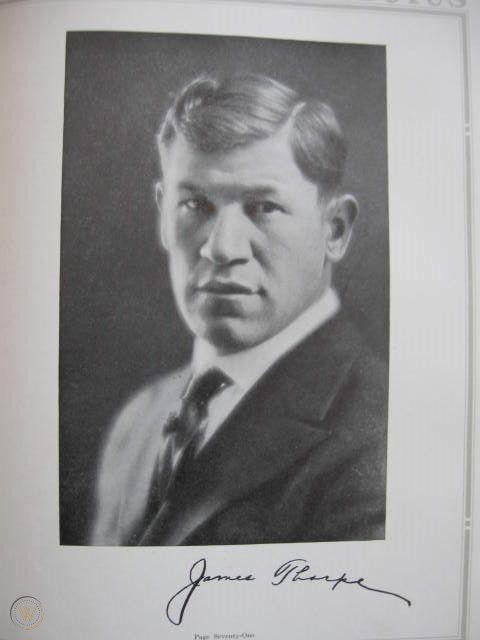

The September 2, 1915 Indianapolis Star ran the headlines: “Jim Thorpe to Coach Indiana”…”World’s Greatest Athlete Will Help Childs with Backfield Men” and “Noted Indian Will Start Work When Baseball Season Is Ended.” The article reported, “This news, coming as it does on the eve of the opening of the season, should serve to act as a tonic to athletics at the Bloomington institution…Thorpe should be – and no doubt will be – of great assistance to Coach Childs in developing a powerful football eleven at Indiana this year. Coach Childs said last night over the long-distance telephone that he proposes to turn over the backfield men to Thorpe and devote most of his own time to the linesmen. Thorpe probably will be unable to join Coach Childs’ staff until the close of the National League baseball season, for he is now playing with the New York Giants.”

The September 28 Indiana Daily Student announced, “James Thorpe, the famous Carlisle Indian athlete, reputed the world’s greatest athlete, will arrive here in a few days to assist Coach Childs in football …Thorpe will take charge of the backfield upon his arrival and will, no doubt, be able to turn out a strong offensive from the fine material on hand…. As Coach Childs has a large squad of nearly forty men, Thorpe will be of great assistance.”

It is hard to put that announcement into perspective today. Imagine if NBA & Olympic star Michael Jordan had paused at the height of his career to come and coach the foundering IU football team. No one knows for sure when Childs contacted Thorpe about joining the Hoosiers football staff, but what is certain is that by early October, Thorpe was in Bloomington.

The Indianapolis star reported, “After some three weeks of anxious waiting, (John) McGraw’s national pastimers turn over to the University coaching staff one of the greatest athletes the world has ever known, James Thorpe. He and his family will arrive in this city Thursday evening at 7 o’clock. Thorpe will take up his duties as assistant coach Friday afternoon…Students, alumni and, in fact, the entire college world looks forward to the coming of this great athlete, with great eagerness to know exactly how his coaching will compare with his known ability as a player. In fact, the thing foremost in the minds of these men is, can this All-American star teach the Indiana backfield men the tricks that made him so famous at Carlisle?”

The Indianapolis star reported, “After some three weeks of anxious waiting, (John) McGraw’s national pastimers turn over to the University coaching staff one of the greatest athletes the world has ever known, James Thorpe. He and his family will arrive in this city Thursday evening at 7 o’clock. Thorpe will take up his duties as assistant coach Friday afternoon…Students, alumni and, in fact, the entire college world looks forward to the coming of this great athlete, with great eagerness to know exactly how his coaching will compare with his known ability as a player. In fact, the thing foremost in the minds of these men is, can this All-American star teach the Indiana backfield men the tricks that made him so famous at Carlisle?”

An article in a Greencastle newspaper noted, “Thorpe, however, wouldn’t arrive in time to help the Hoosiers for their season opener vs. DePauw. Still, as the campus buzzed over the unveiling of plans for a new gymnasium to be built north of Jordan Field, Childs and his IU squad got off to a fast start to the season, beating DePauw 7-0. A player only identified as McIntosh scored the only touchdown of the game in the second quarter.” The campus was abuzz when, a few days after the DePauw victory, it was announced in the Daily Student newspaper that Jim Thorpe would be arriving by train in Bloomington on Thursday, Oct. 7. The news sent a shockwave through the Indiana football community.

Thorpe made his first appearance on campus the next day. Even though it was just a practice, the IU faithful showed up in droves, first gathering at 4 p.m. outside the Student Building before marching through campus to Jordan Field. Chic Griffis, the yell leader for the Hoosiers, taught the standing room only crowd new cheers for the game including one called “nine cheers for Thorpe,” and another named “nine cheers for Childs” as the Hoosiers practiced. A number of alumni made their way into town to get a glimpse of the superstar on the Hoosiers’ staff. The next day, Thorpe made his Hoosier coaching debut against the Miami Redskins.

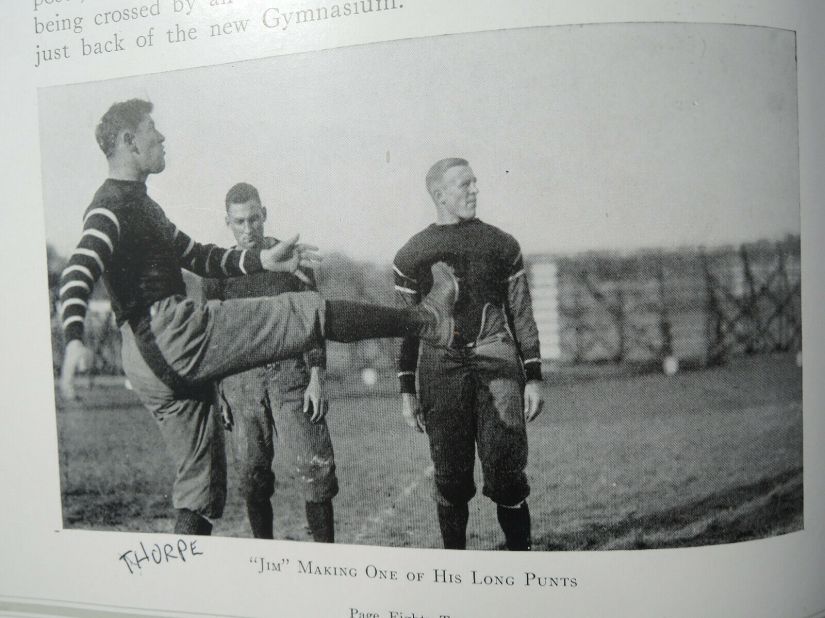

Thorpe’s presence fired up the crowd as IU jumped out to a 34-0 lead by halftime. IU fans thrilled to the sight of Thorpe pacing the sideline. IU hammered Miami 41-0 in front of a huge crowd at Jordan Field. By the next Tuesday, Thorpe was finally getting in some real work with the kickers. The Daily Student noted, “Before the scrimmage, assistant coach Thorpe had the kickers out in the center of the arena instructing them in getting off their punts in good form…The Indian’s long, twisting spirals were not duplicated by either Scott or Whitaker, although both Crimson backs showed much improvement over past performances.”

Thorpe’s presence fired up the crowd as IU jumped out to a 34-0 lead by halftime. IU fans thrilled to the sight of Thorpe pacing the sideline. IU hammered Miami 41-0 in front of a huge crowd at Jordan Field. By the next Tuesday, Thorpe was finally getting in some real work with the kickers. The Daily Student noted, “Before the scrimmage, assistant coach Thorpe had the kickers out in the center of the arena instructing them in getting off their punts in good form…The Indian’s long, twisting spirals were not duplicated by either Scott or Whitaker, although both Crimson backs showed much improvement over past performances.”

A few days later, before the University of Chicago game, Thorpe wowed observers again. The IDS observers noted, “In showing the kickers how to boot the ball, the Indian sent the pigskin seventy and seventy-five yards on an average and was roundly applauded.” Despite Thorpe’s expert training, the Hoosiers’ lost to Amos Alonzo Stagg’s Maroons 13-7. The Chicago media hyped Thorpe’s appearance in the city, completely overlooking the fact that Childs, not Thorpe, was IU’s head coach. One paper described the team as “Indian Jim Thorpe’s Hoosier footballers” and Thorpe far overshadowed the IU football team.

After the game, Thorpe spent his time on Jordan Field practicing kicking by himself. One IDS reporter noted on October 19th, “No one was around – there was no grandstand play – just a step, a quick swing of the leg and a double-thud as the ball hit ground and cleated shoe at the same instant. The kicker was “Jim” Thorpe, late addition to the Crimson coaching staff. He stood on the line which divides the gridiron into two equal portions, a little toward the sideline to avoid the mud. There was a flash of red and brown as his leg swung to meet the rising pigskin and away sailed the ball, end over end, squarely between the white posts at the end of the field. The long kick was accomplished with so much ease and grace that it appeared the least difficult feat in the world, but the big Indian merely smiled. It’s not “being done” on many gridirons this season, however, so old Jordan Field ought to feel mighty proud.”

After the game, Thorpe spent his time on Jordan Field practicing kicking by himself. One IDS reporter noted on October 19th, “No one was around – there was no grandstand play – just a step, a quick swing of the leg and a double-thud as the ball hit ground and cleated shoe at the same instant. The kicker was “Jim” Thorpe, late addition to the Crimson coaching staff. He stood on the line which divides the gridiron into two equal portions, a little toward the sideline to avoid the mud. There was a flash of red and brown as his leg swung to meet the rising pigskin and away sailed the ball, end over end, squarely between the white posts at the end of the field. The long kick was accomplished with so much ease and grace that it appeared the least difficult feat in the world, but the big Indian merely smiled. It’s not “being done” on many gridirons this season, however, so old Jordan Field ought to feel mighty proud.”

With a bye week on the schedule following the Chicago game, the coaching staff focused on the fundamentals during a closed practice on Jordan Field. Barbed wire was placed along the top of the wooden fence surrounding the field and guards were posted at every entrance and more were on hand to discourage anybody peeking through a knothole. It was during Thorpe’s tenure at IU the ground was cleared near the football field for the new Men’s Gymnasium. Tradition claims that Jim Thorpe was on hand for the groundbreaking when axes were handed out and male students chopped down an apple orchard that occupied the site. Coeds handed out cider and sandwiches, and a good time was had by all.

Next, the Hoosiers traveled to Indianapolis’ Washington Field to take on Washington and Lee Oct. 30 in a sold out game attended by an estimated three-quarters of the IU student body. Indiana Governor Sam Ralston was also in attendance. Despite all of Thorpe’s work, IU’s kickers missed twice in the third quarter, one from less than 40 yards out. Those misses were critical in IU’s 7-7 tie with Washington and Lee in front of the largest crowd ever to see a game in pre-Hoosier Dome Indianapolis-8,500. Thorpe’s presence in the capital city translated into big money for the University as IU cleared between $5,000-$6,000 for the game, a staggering amount for the time worth over $ 150,000 today.

Indiana then traveled to Ohio State Nov. 6. Perhaps in shades of things to come, the Buckeyes won 10-9 in a game that saw the Hoosiers flagged for more than 100 yards in penalties. Once again, Thorpe’s work with the kickers didn’t pan out as IU missed five field-goal attempts, including one that skidded across the ground and over the goal line and another that was blocked. Childs returned to Bloomington and drilled his squad hard while Thorpe worked with the offensive players in search of a new kicker. He found one in a freshman walk-on who went 6-of-8 from 40 yards in practice.

Indiana traveled back to Chicago by train for its Nov. 13 battle with Northwestern. After falling behind 6-0 in the first quarter, the Hoosiers scored a pair of touchdowns and kicked both extra points to lead Indiana to a 14-6 victory. At halftime, Thorpe wowed the windy city crowd with a kicking and punting exhibition. By now, reality was setting in for Jim Thorpe. His love for football could not overcome his impatience for coaching others to perform a task that he was still the best in the game at. So Jim Thorpe went back to what he knew best.

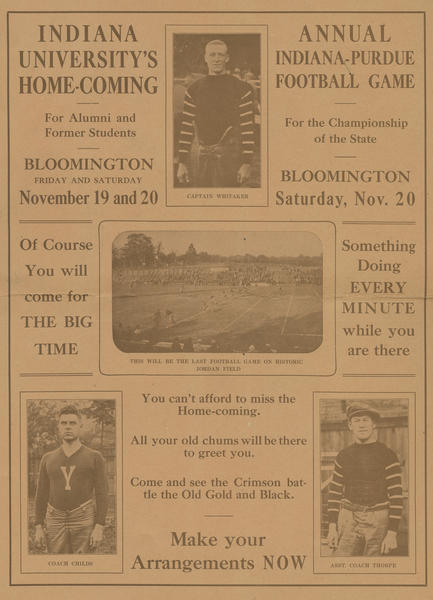

He signed his contract with the Canton Bulldogs of the Ohio League and took a train from Chicago to Massillon (Ohio) while still under contract as an IU coach. In that Nov. 14 game, Thorpe came off the bench for the Bulldogs and although Canton lost 16-0, more than 5,000 fans packed the stands to watch the game. Since previous attendance had been 1,500 fan, it was obvious that most of them were there to see Thorpe. After the game, Thorpe hopped a train back to Bloomington just in time for the old oaken bucket game and Homecoming Weekend. Adding to the excitement was the thought that Jordan Field would be hosting its last game. The new football stadium, next to the Men’s Gymnasium, was under construction.

On the day of the game, Nov. 20, Jordan Field was covered with sawdust to try to dry the water left by the snow, sleet and the rain of the past week. A crowd of more than 7,000 packed Jordan Field to see IU battle the Boilermakers in the old oaken bucket game. Purdue won 7-0. Thorpe put on another punting exhibition for the crowd at halftime. This one wasn’t as spirited as the Chicago exhibition the week before. Understandable because, Thorpe had a game to play the next day in Canton. Thorpe arrived in time for the second game in three weeks between Canton and Massillon, and he took over as head coach of the Bulldogs. In the game, Thorpe drop-kicked a field goal from 45 yards out in the first quarter and added a place kick of 38 yards in the third quarter to push Canton to a 6-0 victory.

On the day of the game, Nov. 20, Jordan Field was covered with sawdust to try to dry the water left by the snow, sleet and the rain of the past week. A crowd of more than 7,000 packed Jordan Field to see IU battle the Boilermakers in the old oaken bucket game. Purdue won 7-0. Thorpe put on another punting exhibition for the crowd at halftime. This one wasn’t as spirited as the Chicago exhibition the week before. Understandable because, Thorpe had a game to play the next day in Canton. Thorpe arrived in time for the second game in three weeks between Canton and Massillon, and he took over as head coach of the Bulldogs. In the game, Thorpe drop-kicked a field goal from 45 yards out in the first quarter and added a place kick of 38 yards in the third quarter to push Canton to a 6-0 victory.

And just like that, the Jim Thorpe Era at IU ended. Thorpe proved to be a better player than he was a coach. His much ballyhooed addition to the staff did not help the Hoosiers that season. They finished with a 3–3–1 record; eighth place in the Western Conference. While Thorpe remained a hero on campus and in the Bloomington community for years to come, coach Childs was fired and replaced in early December by former Nebraska coach Ewald O. “Jumbo” Stiehm. Childs never coached football again. He was sent to France, where he served in the Army during World War I, and eventually he became the athletic director at the Colombes Stadium in Paris. He left the military with the rank of major, and he became an industrial engineer. He passed away in Washington, D.C., in 1960.

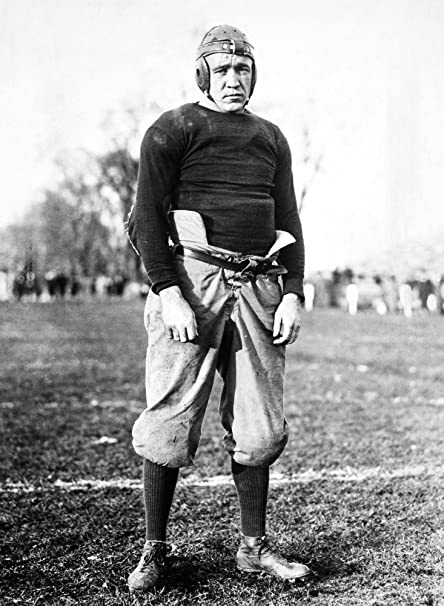

Jim Thorpe left Bloomington to continue his professional athletic career in baseball and football. He helped Canton win three Ohio League championships, reportedly sealing the 1919 title with a wind-assisted 95-yard punt late in the game. Thorpe eventually played for six NFL teams, although he never won a title, and he retired from football in 1928. He played Major League Baseball with the Giants, the Cincinnati Reds and the Boston Braves, compiling a career batting average of .252 in 289 games before retiring in 1919. He would be named the greatest athlete of the first half of the 20th century by the Associated Press and was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1951 and the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1963.

Jim Thorpe left Bloomington to continue his professional athletic career in baseball and football. He helped Canton win three Ohio League championships, reportedly sealing the 1919 title with a wind-assisted 95-yard punt late in the game. Thorpe eventually played for six NFL teams, although he never won a title, and he retired from football in 1928. He played Major League Baseball with the Giants, the Cincinnati Reds and the Boston Braves, compiling a career batting average of .252 in 289 games before retiring in 1919. He would be named the greatest athlete of the first half of the 20th century by the Associated Press and was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1951 and the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1963.

After his playing days ended, Thorpe struggled. He dabbled in Hollywood with little success, descended into alcoholism, and he worked a number of odd jobs later in life, including serving as a doorman, a ditch digger and a security guard. When he was hospitalized for lip cancer in 1950, he was broke and had to be admitted as a charity case. Thorpe finally succumbed to his third heart attack March 28, 1953 at the age of 64. Following his death, the town of Mauch Chunk purchased his remains and erected a monument in his honor, even though there is no proof he ever visited the area in life. The town renamed itself Jim Thorpe, Pa. In 1982, the Olympic committee reinstated Thorpe’s Olympic gold medals from the 1912 games.

One of Thorpe’s odd jobs was serving as a traveling softball umpire. When I was young collector, I purchased an old World War II softball in a box. It belonged to man who had received the ball as his own personal trophy for being named MVP of some long forgotten tournament. He mentioned that the ball had been signed by the tourney umpire. A man named Jim Thorpe. I opened the box and looked at the fountain pen signature, crisp as the day it had been signed. “You probably don’t know who that is.” the old man said. To which I answered, “Oh, I know who it is,” I answered. I’m an IU grad as are both of my children. And for a time, Jim Thorpe was one of us. That ball was sold off many years ago when the responsibility and expense of raising children trumped the need for sentimental objects. But the memory remains,

One of Thorpe’s odd jobs was serving as a traveling softball umpire. When I was young collector, I purchased an old World War II softball in a box. It belonged to man who had received the ball as his own personal trophy for being named MVP of some long forgotten tournament. He mentioned that the ball had been signed by the tourney umpire. A man named Jim Thorpe. I opened the box and looked at the fountain pen signature, crisp as the day it had been signed. “You probably don’t know who that is.” the old man said. To which I answered, “Oh, I know who it is,” I answered. I’m an IU grad as are both of my children. And for a time, Jim Thorpe was one of us. That ball was sold off many years ago when the responsibility and expense of raising children trumped the need for sentimental objects. But the memory remains,

Oh, and that coach that C.C. Childs passed over in favor of Jim Thorpe? Well, that was a young man who was working as a lifeguard at Cedar Point in the summer of 1913. A young man named Knute Rockne. He would go on to become one of the greatest coaches in the history of college football for the Notre Dame Fighting Irish.

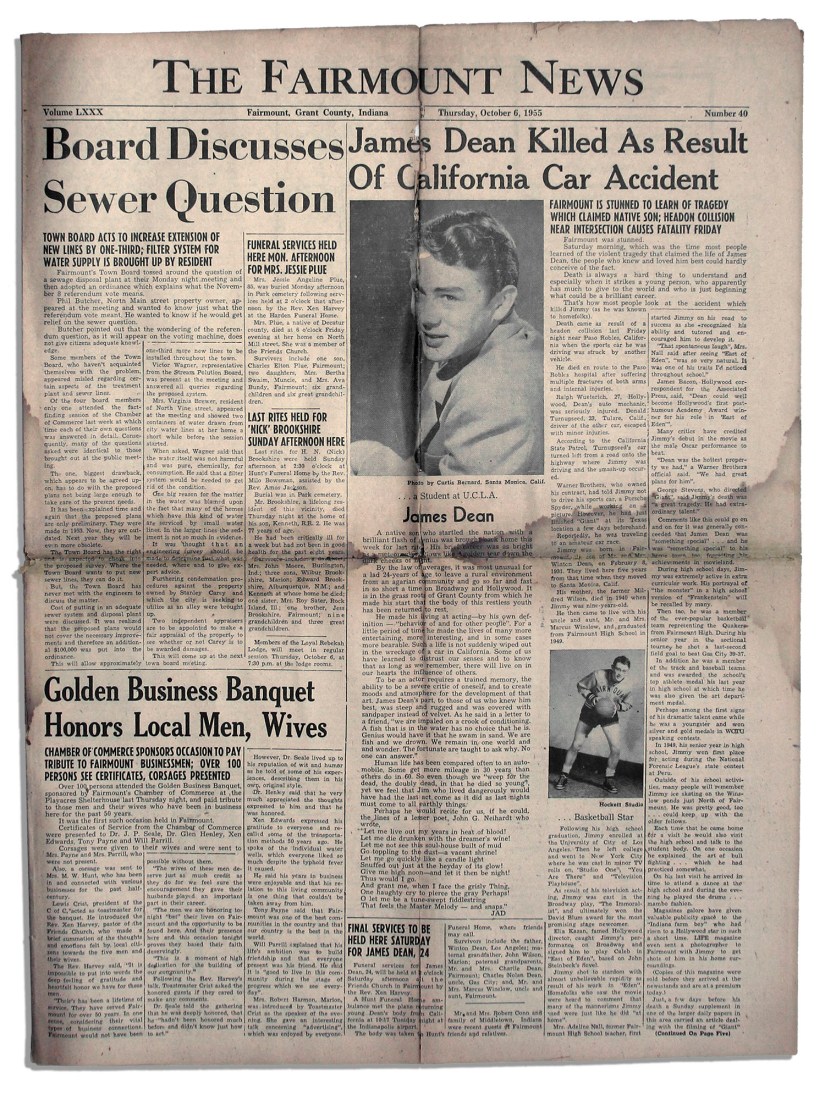

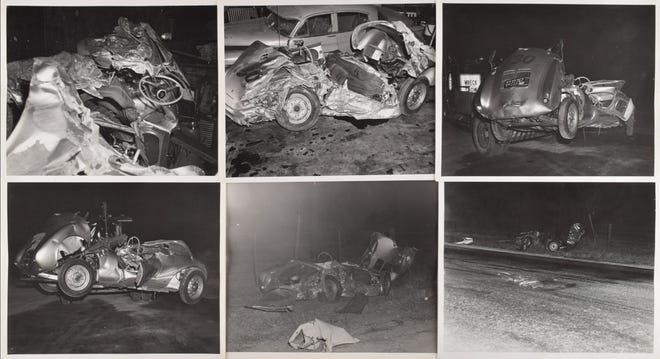

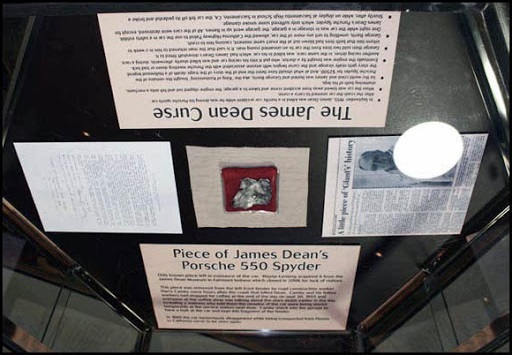

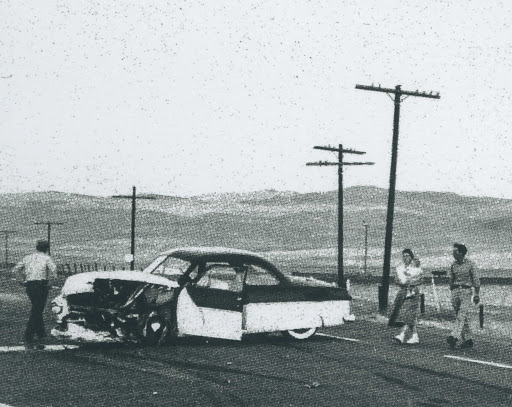

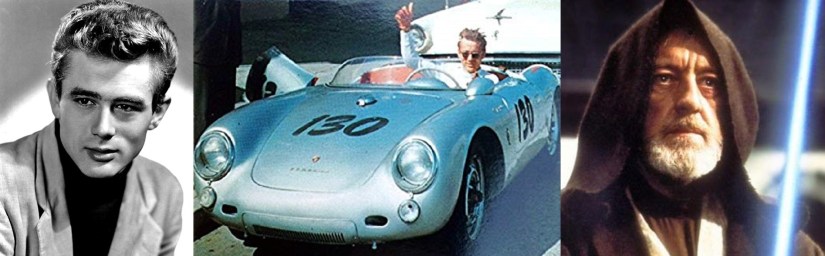

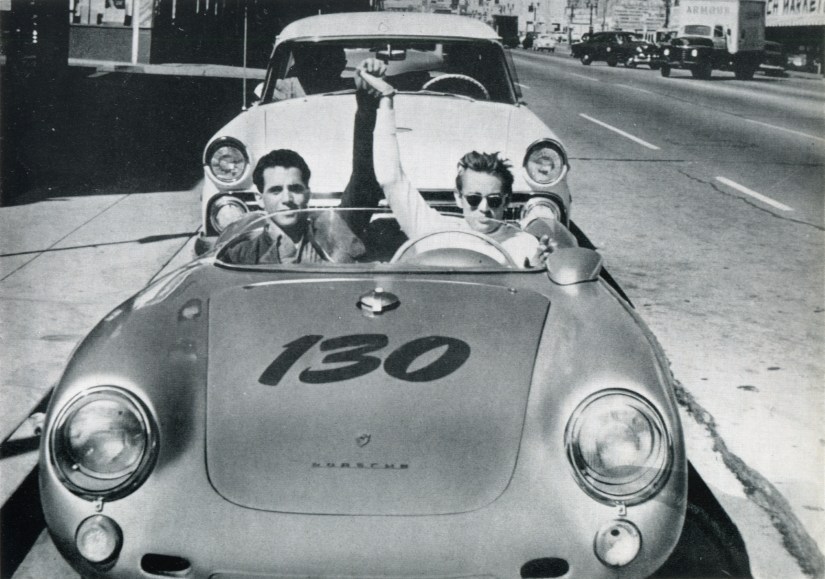

James Dean’s aluminium-bodied Porsche was launched into the air, torn and crushed. But that was not the end of the car’s story. The “curse” of James Dean’s car has become a part of America’s cultural mythology. Some claim that the source of that “curse” was none other than iconic Pop Culture car creator known as the “King of the Kustomizers”, George Barris. It was Barris who created the Batmobile, the Beverly Hillbillies truck, the Munster Koach and Grandpa Munster’s “Drag-U-La” casket car used in the 1960s TV series. It was Barris who painted the number 130 on the doors, front hood and rear trunk of Dean’s Posche Spyder. It was Barris who also stenciled the name “Little Bastard” on the back of the car. And it was Barris who eventually came to own the deathcar.

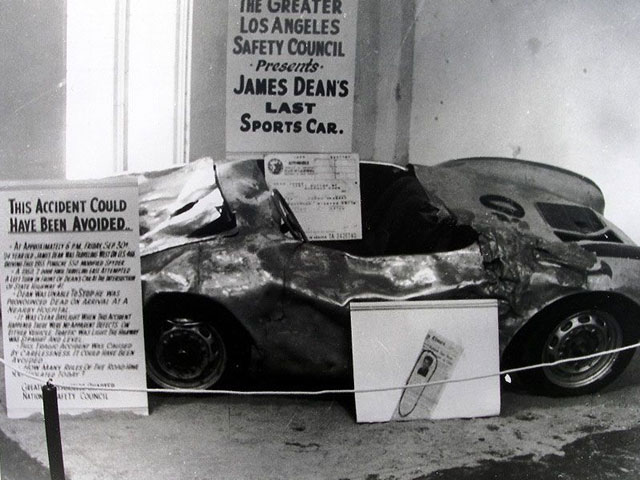

James Dean’s aluminium-bodied Porsche was launched into the air, torn and crushed. But that was not the end of the car’s story. The “curse” of James Dean’s car has become a part of America’s cultural mythology. Some claim that the source of that “curse” was none other than iconic Pop Culture car creator known as the “King of the Kustomizers”, George Barris. It was Barris who created the Batmobile, the Beverly Hillbillies truck, the Munster Koach and Grandpa Munster’s “Drag-U-La” casket car used in the 1960s TV series. It was Barris who painted the number 130 on the doors, front hood and rear trunk of Dean’s Posche Spyder. It was Barris who also stenciled the name “Little Bastard” on the back of the car. And it was Barris who eventually came to own the deathcar. After Dr. Eschrich striped the car of it’s engine and any other salvageable racing components, he evidently sold the Spyder’s mangled chassis to Barris. It is not known exactly how Barris knew Eschrich, but in late-1956, Barris announced that he would rebuild the Porsche. However, as the wrecked chassis had no remaining integral strength, a rebuild proved to be a Herculean task, even for a wizard like Barris. Barris welded aluminum sheet metal over the caved-in left front fender and cockpit. He then beat on the aluminum panels with a 2×4 to try to mimic collision damage. So, likely to protect his investment and reputation, Barris promoted the “curse” by placing the wreck on public display.

After Dr. Eschrich striped the car of it’s engine and any other salvageable racing components, he evidently sold the Spyder’s mangled chassis to Barris. It is not known exactly how Barris knew Eschrich, but in late-1956, Barris announced that he would rebuild the Porsche. However, as the wrecked chassis had no remaining integral strength, a rebuild proved to be a Herculean task, even for a wizard like Barris. Barris welded aluminum sheet metal over the caved-in left front fender and cockpit. He then beat on the aluminum panels with a 2×4 to try to mimic collision damage. So, likely to protect his investment and reputation, Barris promoted the “curse” by placing the wreck on public display. First, Barris loaned the car out to the Los Angeles chapter of the National Safety Council for a local custom car show in 1956. The gruesome display was promoted as: “James Dean’s Last Sports Car”. From 1957 to 1959, the exhibit toured the country in various custom car shows, movie theatres, bowling alleys, and highway safety displays throughout California. It even made an appearance at Indianapolis Raceway Park during the NHRA Drag Racing Championship track’s grand opening in 1960. According to Barris, during those years 1956 to 1960, a mysterious series of accidents, not all of them car crashes, occurred involving the car resulting in serious injuries to spectators and even a truck driver’s death.

First, Barris loaned the car out to the Los Angeles chapter of the National Safety Council for a local custom car show in 1956. The gruesome display was promoted as: “James Dean’s Last Sports Car”. From 1957 to 1959, the exhibit toured the country in various custom car shows, movie theatres, bowling alleys, and highway safety displays throughout California. It even made an appearance at Indianapolis Raceway Park during the NHRA Drag Racing Championship track’s grand opening in 1960. According to Barris, during those years 1956 to 1960, a mysterious series of accidents, not all of them car crashes, occurred involving the car resulting in serious injuries to spectators and even a truck driver’s death.

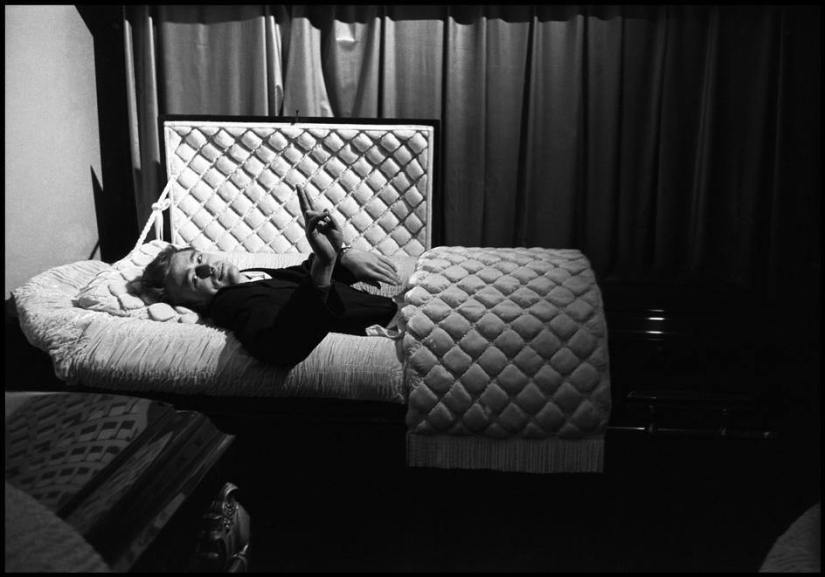

Like many a Hoosier youth, I too had my “James Dean phase”. Some twenty years ago, my wife Rhonda and I took a trip up to Fairmount to visit James Dean country. We were toured around the community by a couple of older gentlemen who graciously pointed out spots the young actor frequented including the family farm, Dean’s old high school, a few of the old stores Dean used to frequent, the cemetery and the funeral home where Dean was prepared for burial. One of the men mentioned, “He had a closed-casket funeral to conceal his severe injuries from his hometown friends and family.” These men had been underclassmen at Fairmount high school and relayed stories of encounters with Dean from their school days. They remarked that when the young method actor returned to Fairmount after making a Pepsi commercial and a bit part on TV, Dean attended a high school dance. “We didn’t like him because he had all of the girls in the room fawning all over him and we couldn’t get a dance.” they said. “We didn’t see him as a big shot from Hollywood, we saw him as a guy trying to steal our dates.”

Like many a Hoosier youth, I too had my “James Dean phase”. Some twenty years ago, my wife Rhonda and I took a trip up to Fairmount to visit James Dean country. We were toured around the community by a couple of older gentlemen who graciously pointed out spots the young actor frequented including the family farm, Dean’s old high school, a few of the old stores Dean used to frequent, the cemetery and the funeral home where Dean was prepared for burial. One of the men mentioned, “He had a closed-casket funeral to conceal his severe injuries from his hometown friends and family.” These men had been underclassmen at Fairmount high school and relayed stories of encounters with Dean from their school days. They remarked that when the young method actor returned to Fairmount after making a Pepsi commercial and a bit part on TV, Dean attended a high school dance. “We didn’t like him because he had all of the girls in the room fawning all over him and we couldn’t get a dance.” they said. “We didn’t see him as a big shot from Hollywood, we saw him as a guy trying to steal our dates.”

Driving along that long two-lane stretch of Central California highway, it’s easy to imagine what James Dean’s last hour was like even though much of today’s road isn’t the same one James Dean traveled on. The route was upgraded and moved slightly north in the 1960s. However, parts of the original can still be found. As you drive west on the last mile to the crash site and look off to your left and you can still see what’s left of the original two-lane road. If you pull off to the side of the road, it’s still possible to walk on part of the crumbling pavement, with weeds sprouting in the middle, and imagine that little silver Porsche speeding past.

Driving along that long two-lane stretch of Central California highway, it’s easy to imagine what James Dean’s last hour was like even though much of today’s road isn’t the same one James Dean traveled on. The route was upgraded and moved slightly north in the 1960s. However, parts of the original can still be found. As you drive west on the last mile to the crash site and look off to your left and you can still see what’s left of the original two-lane road. If you pull off to the side of the road, it’s still possible to walk on part of the crumbling pavement, with weeds sprouting in the middle, and imagine that little silver Porsche speeding past.

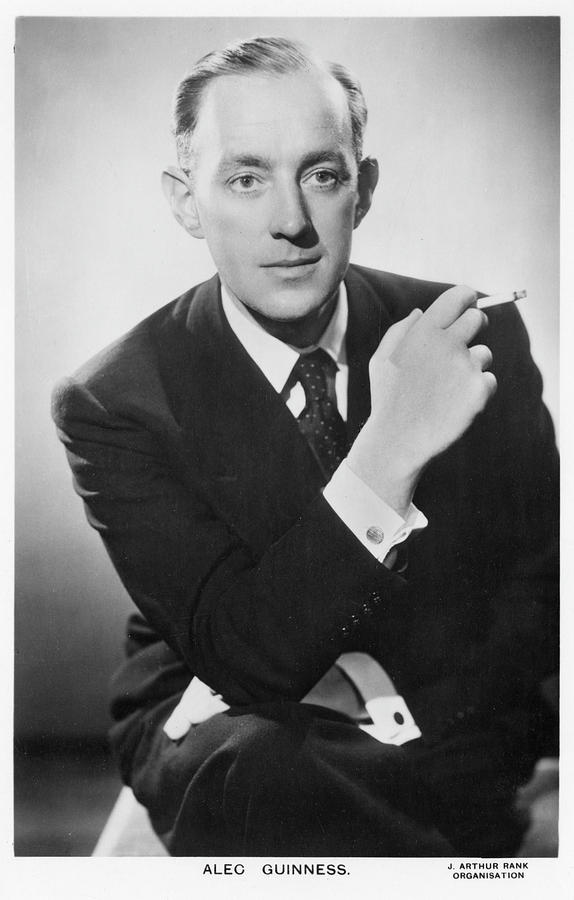

Guinness and Moss followed Dean to the restaurant, but before they reached the door, Dean stopped and said, “I’d like to show you something.” Years later, Guinness recalled “There in the courtyard of this little restaurant was this little silver thing, very smart, all done up in cellophane with a bunch of roses tied to its bonnet.” The young method actor told his new British star, “It’s just been delivered,” said Dean “I haven’t even been in it at all.” Guinness thought the car looked “sinister”. “How fast is it?” he asked. “She’ll do a hundred and fifty,” replied Dean.

Guinness and Moss followed Dean to the restaurant, but before they reached the door, Dean stopped and said, “I’d like to show you something.” Years later, Guinness recalled “There in the courtyard of this little restaurant was this little silver thing, very smart, all done up in cellophane with a bunch of roses tied to its bonnet.” The young method actor told his new British star, “It’s just been delivered,” said Dean “I haven’t even been in it at all.” Guinness thought the car looked “sinister”. “How fast is it?” he asked. “She’ll do a hundred and fifty,” replied Dean. At 3:30 p.m., Dean was stopped by California Highway Patrolman O.V. Hunter at Mettler Station on Wheeler Ridge, just south of Bakersfield, for driving 65 mph in a 55 mph zone. Hickman, following the Spyder in Dean’s Ford “woodie” station wagon pulling the trailer, was also ticketed for driving 20 mph over the limit, as the speed limit for all vehicles towing a trailer was 45 mph. After receiving the citations, Dean and Hickman turned left onto SR 166 / 33 to bypass Bakersfield’s congested downtown district. This bypass became known as “the racer’s road”, a popular short-cut for sports car drivers going to Salinas. The racer’s road went directly to Blackwells Corner at U.S. Route 466 (later SR 46). Around 5:00 p.m., Dean stopped at Blackwells Corner for “apples and Coca-Cola” and met up briefly with fellow racers Lance Reventlow and Bruce Kessler, who were also on their way to Salinas in Reventlow’s Mercedes-Benz 300 SL coupe. As Reventlow and Kessler were leaving, they all agreed to meet for dinner that night in Paso Robles.

At 3:30 p.m., Dean was stopped by California Highway Patrolman O.V. Hunter at Mettler Station on Wheeler Ridge, just south of Bakersfield, for driving 65 mph in a 55 mph zone. Hickman, following the Spyder in Dean’s Ford “woodie” station wagon pulling the trailer, was also ticketed for driving 20 mph over the limit, as the speed limit for all vehicles towing a trailer was 45 mph. After receiving the citations, Dean and Hickman turned left onto SR 166 / 33 to bypass Bakersfield’s congested downtown district. This bypass became known as “the racer’s road”, a popular short-cut for sports car drivers going to Salinas. The racer’s road went directly to Blackwells Corner at U.S. Route 466 (later SR 46). Around 5:00 p.m., Dean stopped at Blackwells Corner for “apples and Coca-Cola” and met up briefly with fellow racers Lance Reventlow and Bruce Kessler, who were also on their way to Salinas in Reventlow’s Mercedes-Benz 300 SL coupe. As Reventlow and Kessler were leaving, they all agreed to meet for dinner that night in Paso Robles.

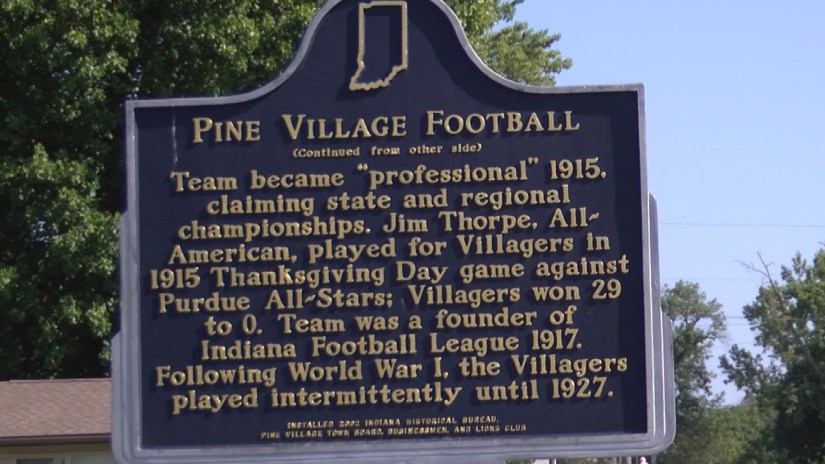

Thorpe played professional football in 1913 as a member of the Indiana-based Pine Village Pros, a team that had a several-season winning streak against local teams during the 1910s. Also that year, Thorpe signed pro contracts to play baseball with the New York Giants and football for the Chicago Cardinals and Canton (Ohio) Bulldogs. The Bulldogs paid Thorpe $ 250 per game ($5,919 today) a huge sum for the time. Overnight, the Bulldogs went from drawing 1,200 fans per game to 8,000. Thorpe was front page news, leading the Bulldogs to league championships in 1916, 1917 and 1919. In 1920, the Bulldogs and 13 other teams formed the APFA (American Professional Football Association) the forerunner of today’s NFL and Thorpe was elected the league’s first president. You might say that Jim Thorpe was a big deal.

Thorpe played professional football in 1913 as a member of the Indiana-based Pine Village Pros, a team that had a several-season winning streak against local teams during the 1910s. Also that year, Thorpe signed pro contracts to play baseball with the New York Giants and football for the Chicago Cardinals and Canton (Ohio) Bulldogs. The Bulldogs paid Thorpe $ 250 per game ($5,919 today) a huge sum for the time. Overnight, the Bulldogs went from drawing 1,200 fans per game to 8,000. Thorpe was front page news, leading the Bulldogs to league championships in 1916, 1917 and 1919. In 1920, the Bulldogs and 13 other teams formed the APFA (American Professional Football Association) the forerunner of today’s NFL and Thorpe was elected the league’s first president. You might say that Jim Thorpe was a big deal.

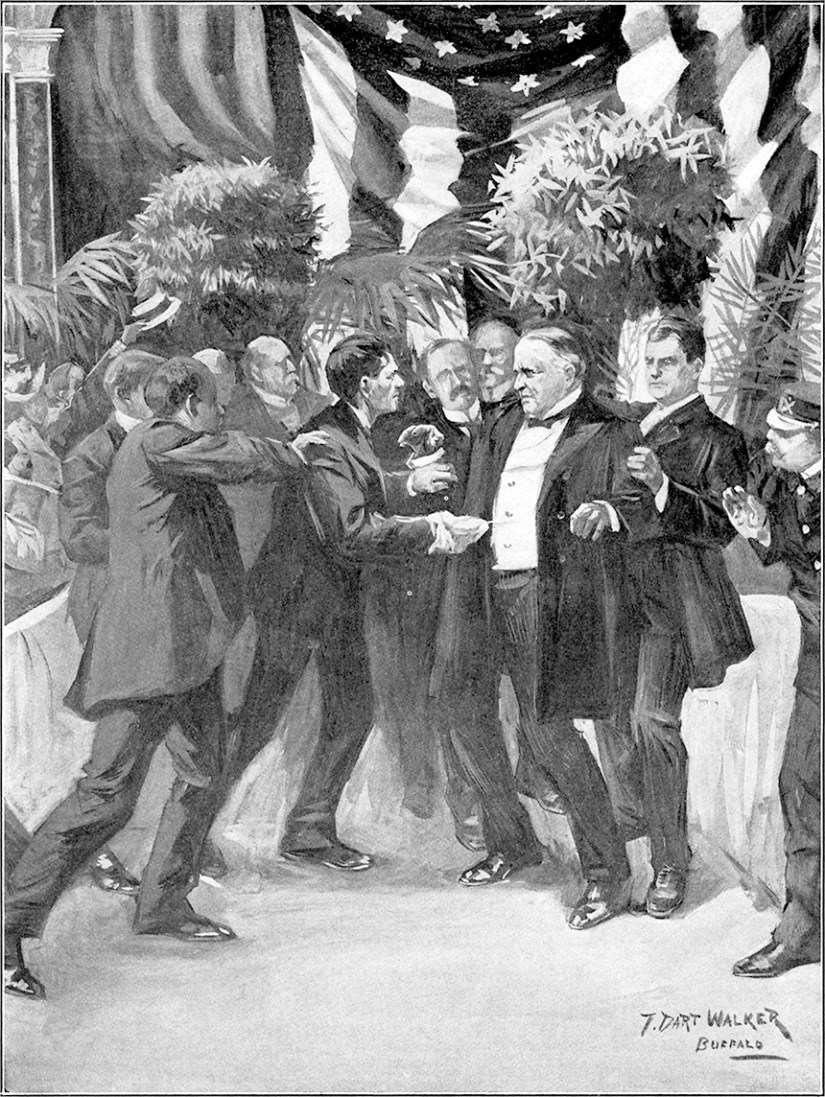

The president was scheduled to meet the thousands of people who, in spite of the oppressive heat, were waiting at the Temple of Music on the north side of the fairgrounds. In that line, no one stood out more than James “Big Ben” Parker, a six-foot six inch, 250 pound “Negro” waiter from Atlanta who has been laid off by the exposition’s Plaza Restaurant only days before. One could conclude that “Big Ben” was the angriest man in the room and the one the Secret Service should be watching. However, that sobriquet would belong to the man standing immediately in front of the gentle giant. A stoop-shouldered, nervous little man whose hand was wrapped in a handkerchief.

The president was scheduled to meet the thousands of people who, in spite of the oppressive heat, were waiting at the Temple of Music on the north side of the fairgrounds. In that line, no one stood out more than James “Big Ben” Parker, a six-foot six inch, 250 pound “Negro” waiter from Atlanta who has been laid off by the exposition’s Plaza Restaurant only days before. One could conclude that “Big Ben” was the angriest man in the room and the one the Secret Service should be watching. However, that sobriquet would belong to the man standing immediately in front of the gentle giant. A stoop-shouldered, nervous little man whose hand was wrapped in a handkerchief. The first bullet sheared a button off of McKinley’s vest, the second tore into the President’s abdomen. The handkerchief burst into flames and fell to the floor. McKinley lurched forward as Czolgosz took aim for a third shot. Within seconds after the second pistol shot, Big Ben Parker was grappling with the adrenaline charged assassin. Secret service special agent Samuel Ireland described the scene: “Parker struck the assassin in the neck with one hand and with the other reached for the revolver which had been discharged through the handkerchief and the shots had set fire to the linen. While on the floor Czolgosz again tried to discharge the revolver but before he got to the president the Negro knocked it from his hand.” A split second after Parker struck Czolgosz, so did Buffalo detective John Geary and one of the artillerymen, Francis O’Brien. Czolgosz disappeared beneath a pile of men, some of whom were punching or hitting him with rifle butts. The assassin cried out, “I done my duty.”

The first bullet sheared a button off of McKinley’s vest, the second tore into the President’s abdomen. The handkerchief burst into flames and fell to the floor. McKinley lurched forward as Czolgosz took aim for a third shot. Within seconds after the second pistol shot, Big Ben Parker was grappling with the adrenaline charged assassin. Secret service special agent Samuel Ireland described the scene: “Parker struck the assassin in the neck with one hand and with the other reached for the revolver which had been discharged through the handkerchief and the shots had set fire to the linen. While on the floor Czolgosz again tried to discharge the revolver but before he got to the president the Negro knocked it from his hand.” A split second after Parker struck Czolgosz, so did Buffalo detective John Geary and one of the artillerymen, Francis O’Brien. Czolgosz disappeared beneath a pile of men, some of whom were punching or hitting him with rifle butts. The assassin cried out, “I done my duty.” A Los Angeles Times story said that “with one quick shift of his clenched fist, he [Parker] knocked the pistol from the assassin’s hand. With another, he spun the man around like a top and with a third, he broke Czolgosz’s nose. A fourth split the assassin’s lip and knocked out several teeth.” In Parker’s own account, given to a newspaper reporter a few days later, he said, “I heard the shots. I did what every citizen of this country should have done. I am told that I broke his nose—I wish it had been his neck. I am sorry I did not see him four seconds before. I don’t say that I would have thrown myself before the bullets. But I do say that the life of the head of this country is worth more than that of an ordinary citizen and I should have caught the bullets in my body rather than the President should get them.” In a separate interview for the New York Journal, Parker remarked “just think, Father Abe freed me, and now I saved his successor from death, provided that bullet he got into the president don’t kill him.”

A Los Angeles Times story said that “with one quick shift of his clenched fist, he [Parker] knocked the pistol from the assassin’s hand. With another, he spun the man around like a top and with a third, he broke Czolgosz’s nose. A fourth split the assassin’s lip and knocked out several teeth.” In Parker’s own account, given to a newspaper reporter a few days later, he said, “I heard the shots. I did what every citizen of this country should have done. I am told that I broke his nose—I wish it had been his neck. I am sorry I did not see him four seconds before. I don’t say that I would have thrown myself before the bullets. But I do say that the life of the head of this country is worth more than that of an ordinary citizen and I should have caught the bullets in my body rather than the President should get them.” In a separate interview for the New York Journal, Parker remarked “just think, Father Abe freed me, and now I saved his successor from death, provided that bullet he got into the president don’t kill him.”

Historians agree that Czolgosz’s trial was a sham. Sadly, what should have been Big Ben Parker’s time to shine instead became his disappearing act. Prior to the trial, which began September 23, 1901, Parker was expected to be a major character in the assassination saga. Instead,the trial minimized Parker’s participation in the events of three weeks prior. Parker was never asked to testify and those few participants who did never identified Big Ben as the person who first subdued the assassin. Czolgosz’s sanity was never questioned and the case was closed twenty-four hours after it opened. Newspaper reports after the trial failed to mention Big Ben’s role and witnesses, including lawyers and Secret Service agents, began to enlarge their own roles in the tragedy by going as far as saying they “saw no Negro involved” whatsoever.

Historians agree that Czolgosz’s trial was a sham. Sadly, what should have been Big Ben Parker’s time to shine instead became his disappearing act. Prior to the trial, which began September 23, 1901, Parker was expected to be a major character in the assassination saga. Instead,the trial minimized Parker’s participation in the events of three weeks prior. Parker was never asked to testify and those few participants who did never identified Big Ben as the person who first subdued the assassin. Czolgosz’s sanity was never questioned and the case was closed twenty-four hours after it opened. Newspaper reports after the trial failed to mention Big Ben’s role and witnesses, including lawyers and Secret Service agents, began to enlarge their own roles in the tragedy by going as far as saying they “saw no Negro involved” whatsoever.

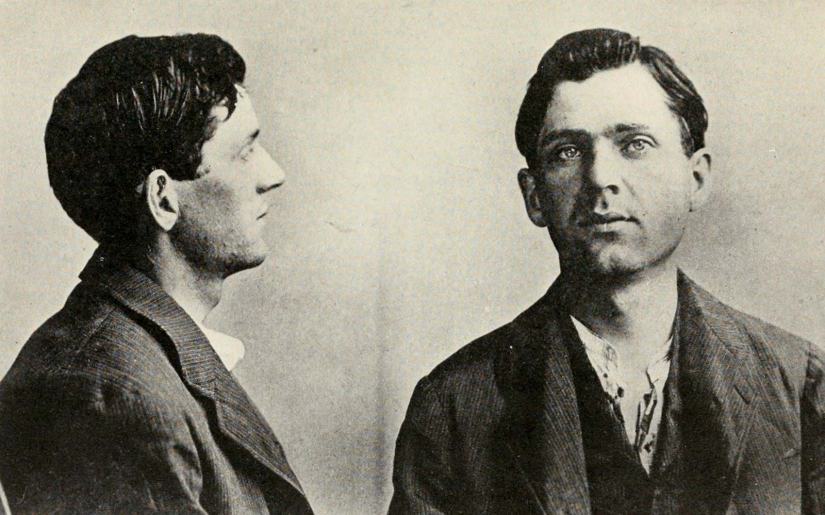

Just as Big Ben is the forgotten figure in the McKinley assassination saga, Leon Czolgosz is the least known of all presidential assassins. Prior to his execution Czolgosz met with two priests and said, “No. Damn them. Don’t send them here again. I don’t want them. And don’t you have any praying over me when I’m dead. I don’t want it. I don’t want any of their damned religion.” Czolgosz was electrocuted on October 29, 1901 at Auburn penitentiary. Initially, Czolgosz’s family wanted the body. The warden convinced them that it would be a bad idea, that relic hunters would disturb his grave, or worse, that unscrupulous carnival promoters would want to display the body in traveling sideshows.

Just as Big Ben is the forgotten figure in the McKinley assassination saga, Leon Czolgosz is the least known of all presidential assassins. Prior to his execution Czolgosz met with two priests and said, “No. Damn them. Don’t send them here again. I don’t want them. And don’t you have any praying over me when I’m dead. I don’t want it. I don’t want any of their damned religion.” Czolgosz was electrocuted on October 29, 1901 at Auburn penitentiary. Initially, Czolgosz’s family wanted the body. The warden convinced them that it would be a bad idea, that relic hunters would disturb his grave, or worse, that unscrupulous carnival promoters would want to display the body in traveling sideshows. His family agreed that the prison should take care of the funeral arrangements by giving the assassin a decent burial within the protection of the prison grounds. When Leon Czolgosz was buried in the Auburn prison cemetery, yards away from where he was executed, unbeknownst to the family, the decision was made to have his body destroyed. The local crematorium refused to undertake the job. So the assassin’s body was placed in a rough pine box and lowered into the ground which had been coated with quicklime. The lid was removed and two barrels of quicklime powder was caked on top of the body. Then sulfuric acid was poured on top of that followed by another two layers of quicklime.

His family agreed that the prison should take care of the funeral arrangements by giving the assassin a decent burial within the protection of the prison grounds. When Leon Czolgosz was buried in the Auburn prison cemetery, yards away from where he was executed, unbeknownst to the family, the decision was made to have his body destroyed. The local crematorium refused to undertake the job. So the assassin’s body was placed in a rough pine box and lowered into the ground which had been coated with quicklime. The lid was removed and two barrels of quicklime powder was caked on top of the body. Then sulfuric acid was poured on top of that followed by another two layers of quicklime. Their intention was to make the anarchist’s body dematerialize. What the prison officials did not know was that when quicklime (calcium oxide) and sulfuric acid are combined, a chemical reaction occurs which creates an exterior coating best compared to plaster of paris. Since the shell is insoluble in water, the coating acts as a protective layer thus preventing further attack on the corpse by the acid. It is entirely possible that the body of Czolgosz was preserved in perpetuity accidentally.

Their intention was to make the anarchist’s body dematerialize. What the prison officials did not know was that when quicklime (calcium oxide) and sulfuric acid are combined, a chemical reaction occurs which creates an exterior coating best compared to plaster of paris. Since the shell is insoluble in water, the coating acts as a protective layer thus preventing further attack on the corpse by the acid. It is entirely possible that the body of Czolgosz was preserved in perpetuity accidentally.