Original publish date: September 18, 2013

Original publish date: September 18, 2013

But February made me shiver~With every paper I’d deliver~Bad news on the doorstep~I couldn’t take one more step~I can’t remember if I cried~When I read about his widowed bride~But something touched me deep inside~The day the music died~Bye-bye, Miss American Pie~Drove my Chevy to the levy~But the levy was dry~And them good old boys were drinking whiskey and rye~Singing this’ll be the day that I die.

I don’t know what that song means to you, but for me, it brings back a sad memory from my childhood. I know why it was written. Although Don McLean has never clearly defined the meaning of the song, he dedicated the album to Buddy Holly. And though it is clearly an homage to Buddy Holly, Richie Valens and the Big Bopper, none of the artists are mentioned by name in the song. When asked to decipher the lyrics, McLean explained, “You will find many interpretations of my lyrics but none of them by me…They’re beyond analysis. They’re poetry…Sorry to leave you all on your own like this but long ago I realized that songwriters should make their statements and move on, maintaining a dignified silence.”

The song was released in 1971 and eventually rose to number-one on the U.S. charts, where it remained for four weeks in 1972. It is generally considered to be one of the finest rock / pop songs ever written and anyone born before 1980 can sign the song word-for-word. It’s one of those songs that if most people were awakened at 3 in the morning and asked to sing it, they could.

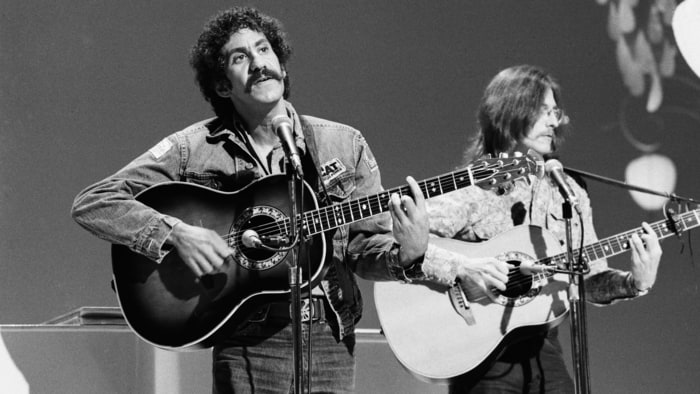

To me, it reminds me of a day 40 years ago this week, September 20, 1973. The day Jim Croce died. Like McLean in 1959, I was a paperboy in 1973 and I discovered the news by cutting open my stack of newspapers in preparation for fold-and-deliver. As fate would have it, the news came across the AM radio at exactly the same I was opening my stack. I don’t consider myself a die-hard Jim Croce fan. I listen to his songs occasionally and still believe that “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown” ranks with Mclean’s “American Pie” as one of the greatest American pop songs ever written, but that’s about it. Still, I can remember the moment of that tragic discovery as if it happened yesterday.

To me, it reminds me of a day 40 years ago this week, September 20, 1973. The day Jim Croce died. Like McLean in 1959, I was a paperboy in 1973 and I discovered the news by cutting open my stack of newspapers in preparation for fold-and-deliver. As fate would have it, the news came across the AM radio at exactly the same I was opening my stack. I don’t consider myself a die-hard Jim Croce fan. I listen to his songs occasionally and still believe that “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown” ranks with Mclean’s “American Pie” as one of the greatest American pop songs ever written, but that’s about it. Still, I can remember the moment of that tragic discovery as if it happened yesterday.

It seemed to me that Croce’s death was not unlike a Greek tragedy. Here was a man who, but all accounts, was a very nice guy. Everyone who knew him, liked him. He had worked hard for a decade to become an overnight sensation and died tragically just as he was reaching the top. Being the morose child I was and the nostalgic person I have become, I couldn’t help but wonder what might have been had Croce lived. With his natural ability to spin a phrase within a musical story, there can be little doubt that we lost many classic songs when that plane went down. Keep in mind, I’m still mad at John Belushi for checking out too soon. Although I love John Candy, Belushi would have owned that Uncle Buck movie. But that’s ANOTHER story.

Croce’s death was a blow to me. True, it came after the deaths of Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, Duane Allman and Gram Parsons (who died the day before Croce’s death), but these deaths seemed almost predictable. After all, the string of “death by lifestyle” in the music business stretches all the way back to Hank Williams, Brian Jones, Robert Johnson and Frankie Lyman. But Croce’s sudden passing, like Holly/Valens/Richardson a generation before and Otis Redding contemporarily, was different. Sudden, shocking, unexpected, undeserved perhaps?

Jim Croce’s life story can’t help but bring a smile to anyone who hears it. He was born in South Philly on January 10, 1943. Jimmy took a strong interest in music and by age five, he had learned his first song on the accordion: “Lady of Spain.” Croce did not take music seriously until he studied at Villanova, where he formed bands and performed at fraternity parties, coffee houses, and universities around Philadelphia, playing “anything that the people wanted to hear: blues, rock, acappella, railroad music… anything.” Croce’s band was chosen for a foreign exchange tour of Africa, Middle East, and Yugoslavia. He later said, “we just ate what the people ate, lived in the woods, and played our songs. Of course they didn’t speak English over there but if you mean what you’re singing, people understand.” Croce met his future wife Ingrid Jacobson at a “hootenanny” at the Philadelphia Convention Hall, where he was judging a contest.

From the mid-1960s to early 1970s, Croce performed with his wife as a duo. At first, their performances included covers by Gordon Lightfoot, Joan Baez, and Woody Guthrie, but in time they began writing their own music. Croce and Ingrid married in 1966, and Jim converted to Judaism, as his wife was Jewish. This in spite of the fact that he was generally anti-organized religion.

He enlisted in the Army National Guard that same year to avoid being drafted and deployed to Vietnam. Jim served on active duty for four months, leaving just a week after his honeymoon. Croce, who was not good with authority, had to go through basic training twice. He said he would be prepared if “there’s ever a war where we have to defend ourselves with mops”.

In 1968, the Croces’ moved to New York City, settling in the Bronx, where they recorded their first album with Capitol Records. During the next two years, they drove more than 300,000 miles, playing small clubs and college concerts promoting their album.

Becoming disillusioned by the music business and New York City, they sold all but one guitar to pay the rent and returned to the Pennsylvania countryside, settling in an old farm in Lyndell. Croce got a job driving trucks and working construction to pay the bills. All the while Jim continued to write songs, many featuring the characters he met at local bars, truck stops and jobsites.

The couple returned to Philadelphia and Croce decided to be “serious” about becoming a productive member of society. He landed a job at a Philadelphia R&B AM radio station, WHAT, where he translated commercials into “soul”. “I’d sell airtime to Bronco’s Poolroom and then write the spot: “You wanna be cool, and you wanna shoot pool… dig it.” See what I mean? Croce’s story brings a smile to your face.

In 1972, Croce signed a three-record deal with ABC Records and released two albums, “You Don’t Mess Around with Jim” and “Life and Times”. The singles “You Don’t Mess Around with Jim”, “Operator (That’s Not the Way It Feels)”, and “Time in a Bottle” received heavy airplay and “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown” hit No. 1 on the American charts in July of 1973. By then, the Croces’ had again relocated to San Diego, California.

As his career picked up, Croce began touring the country performing gigs in large coffee houses, on college campuses, and at folk festivals. The music business in 1973 was by no means the mega-millions business to has become today and the Croce’s financial situation remained dire. The record company had fronted him the money to record the album, and much of the money the album earned went to repay that advance. In February 1973, Croce traveled to Europe playing concerts in London, Paris, and Amsterdam to rave reviews. Croce also began appearing on television, principally Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert and The Midnight Special, which he co-hosted. Croce finished recording the album “I Got a Name” one week before his death. After nonstop touring, Croce grew increasingly homesick, and decided to take a break from music and settle down with his wife and infant son after his “Life and Times” tour was completed.

On Thursday, September 19, 1973, Croce’s single “I Got a Name” was released. The next day, after a gig at Northwestern State University’s Prather Coliseum, Jim Croce and five others boarded a chartered Beechcraft E18S twin-engine airplane taking off from the Natchitoches Regional Airport in Natchitoches, Louisiana. The group included musician, songwriter Maury Muehleisen, an artist best known for his live accompaniment with, and strong influence on, the Jim Croce sound. Along with comic George Stevens, Croce’s opening act, manager and booking agent Kenneth D. Cortose, road manager Dennis Rast, and pilot Robert N. Elliott. Croce was flying to Sherman, Texas, for a gig at Austin College.

On Thursday, September 19, 1973, Croce’s single “I Got a Name” was released. The next day, after a gig at Northwestern State University’s Prather Coliseum, Jim Croce and five others boarded a chartered Beechcraft E18S twin-engine airplane taking off from the Natchitoches Regional Airport in Natchitoches, Louisiana. The group included musician, songwriter Maury Muehleisen, an artist best known for his live accompaniment with, and strong influence on, the Jim Croce sound. Along with comic George Stevens, Croce’s opening act, manager and booking agent Kenneth D. Cortose, road manager Dennis Rast, and pilot Robert N. Elliott. Croce was flying to Sherman, Texas, for a gig at Austin College.

At 10:45 pm, less than an hour after Croce walked off the stage, the plane crashed after take off. Everyone on board was killed instantly. The plane traveled an estimated 250 yards south of the runway rising some 30 feet in the air before clipping a tree. Investigators said the tree, a large pecan, was the only tree for hundreds of yards. The weather was dark, but with a clear sky, calm winds, and over five miles of visibility with light haze. At the time of the crash, Sheriff Sam James said. “For some reason they didn’t gain altitude fast enough. It flipped, landed upright and was turned completely around.” The pilot, was thrown clear of the wreckage. The other victims were found in the plane.

The official report from the NTSB listed the probable cause as the pilot’s failure to see and avoid obstructions due to pilot physical impairment and fog obstructing vision. The 57-year-old charter pilot suffered from severe coronary artery disease and had run three miles to the airport from a motel. He had an ATP Certificate, 14,290 hours total flight time and 2,190 hours in the Beech 18 type. A later investigation placed sole blame for the accident on pilot error due to his downwind takeoff into a “black hole”.

The album “I Got a Name” was released on December 1, 1973. The posthumous release included three hits: “Workin’ at the Car Wash Blues”, “I’ll Have to Say I Love You in a Song”, and the title song. The album reached No. 2 and “I’ll Have to Say I Love You in a Song” reached No. 9 on the singles chart. The news of the singer’s death sparked a renewed interest in Croce’s previous albums. Consequently, three months later on December 29, 1973, “Time in a Bottle”, originally released on Croce’s first album the year before, hit number one. It became the third posthumous chart-topping song of the rock era following Otis Redding’s “Dock of the Bay” and Janis Joplin’s “Me and Bobby McGee”. A greatest hits package entitled Photographs & Memories was released in 1974.

Jim Croce was buried at Haym Salomon Memorial Park in Frazer, Pennsylvania just outside of Philadelphia. A letter Jim had written to his wife Ingrid arrived after his death. In that poignant letter Croce stated his intention to quit music and stick to writing short stories and movie scripts as a career. In essence, Jim intended to withdraw from public life to spend more time with his wife and unborn child. The song “Time in a Bottle”, which hit number one after Jimmy died, was written for his then-unborn son, A. J. Croce. How can you not be touched by such a story? This week, kiss your wife or significant other. Hug or call your kid. And in short, enjoy life for a moment. If not for yourself, do it for Jim.

Original publish date: August 18, 2013

Original publish date: August 18, 2013 That August night began no differently from any other evening for John and May. John made and received phone calls, watched TV and listened to the day’s recorded studio work while making notes. The 52nd Street apartment was hot that night, but by 8 O’ Clock the air had cooled off enough for May to turn off the air conditioner and open the windows to catch the breeze coming off the river. Just a few feet off the apartment’s living room was the building’s roof, accessible through a side window. This rooftop acted as the couple’s private observation deck, offering a million dollar view of New York’s Eastside. The haze had now cleared over the cityscape and around 8:30 p.m., May decided to take a shower, leaving Lennon alone in the living room reviewing mock-ups of his new record’s cover. The cover art on the final product would be a painting by a 12-year-old John Lennon.

That August night began no differently from any other evening for John and May. John made and received phone calls, watched TV and listened to the day’s recorded studio work while making notes. The 52nd Street apartment was hot that night, but by 8 O’ Clock the air had cooled off enough for May to turn off the air conditioner and open the windows to catch the breeze coming off the river. Just a few feet off the apartment’s living room was the building’s roof, accessible through a side window. This rooftop acted as the couple’s private observation deck, offering a million dollar view of New York’s Eastside. The haze had now cleared over the cityscape and around 8:30 p.m., May decided to take a shower, leaving Lennon alone in the living room reviewing mock-ups of his new record’s cover. The cover art on the final product would be a painting by a 12-year-old John Lennon. Bob Gruen arrived and John excitedly told the photographer what had transpired. Gruen later recalled “I took the film home and put John’s roll between two rolls of film I’d taken earlier that day and developed them”. “My two rolls of film came out perfectly but John’s roll was blank. Later I asked him ” did you call the newspaper?” and he said “I’m not going to call up the newspaper and say, This is John Lennon and I saw a flying saucer last night”… So Bob Gruen called up the local police precinct and asked if anyone had reported a UFO or flying saucer. The police responded with “Where? Up on the East Side? You’re the third call on it”. Then Bob called the Daily News and they said, “On the East Side? Five people reported it”. Finally, Gruen called the ultra-conservative New York Times and asked a reporter if anybody had reported a flying saucer? The reporter hung up on him.

Bob Gruen arrived and John excitedly told the photographer what had transpired. Gruen later recalled “I took the film home and put John’s roll between two rolls of film I’d taken earlier that day and developed them”. “My two rolls of film came out perfectly but John’s roll was blank. Later I asked him ” did you call the newspaper?” and he said “I’m not going to call up the newspaper and say, This is John Lennon and I saw a flying saucer last night”… So Bob Gruen called up the local police precinct and asked if anyone had reported a UFO or flying saucer. The police responded with “Where? Up on the East Side? You’re the third call on it”. Then Bob called the Daily News and they said, “On the East Side? Five people reported it”. Finally, Gruen called the ultra-conservative New York Times and asked a reporter if anybody had reported a flying saucer? The reporter hung up on him. Hand drawn, autographed UFO sketch by John Lennon.

Hand drawn, autographed UFO sketch by John Lennon.

Original publish date: June 29, 2015

Original publish date: June 29, 2015 Paul, sharply dressed in a white, silver flecked jacket and black stovepipe pants with a guitar strapped to his back, whipped out the guitar and began playing Eddie Cochran’s “Twenty Flight Rock” followed by Gene Vincent’s “Be Bop A Lula” before launching into a medley of Little Richard songs. Lennon was floored by the demonstration. McCartney sealed the deal by tuning Lennon’s guitar and writing out the chords and lyrics to some of the songs he’d just played.

Paul, sharply dressed in a white, silver flecked jacket and black stovepipe pants with a guitar strapped to his back, whipped out the guitar and began playing Eddie Cochran’s “Twenty Flight Rock” followed by Gene Vincent’s “Be Bop A Lula” before launching into a medley of Little Richard songs. Lennon was floored by the demonstration. McCartney sealed the deal by tuning Lennon’s guitar and writing out the chords and lyrics to some of the songs he’d just played. But wait, there is proof. That July 6, 1957 Quarrymen’s set was recorded by a member of St Peter’s Youth Club, Bob Molyneux, on his portable Grundig reel-to-reel tape recorder. Made just moments after that historic meeting, it remains the earliest known recording of Lennon. The three-inch reel includes Lennon’s performances of two songs; “Puttin’ on the Style,” a No. 1 hit at the time for Lonnie Donegan, and “Baby Let’s Play House,” an Arthur Gunter song made popular by Elvis Presley. In 1965 Lennon used a line from the Gunter song – “I’d rather see you dead, little girl, than to be with another man”- as the opening line of his own “Run for Your Life”. In 1963, Molyneux offered the tape to Lennon, through Ringo Starr. But Lennon never responded, so Molyneux put the tape in a vault.

But wait, there is proof. That July 6, 1957 Quarrymen’s set was recorded by a member of St Peter’s Youth Club, Bob Molyneux, on his portable Grundig reel-to-reel tape recorder. Made just moments after that historic meeting, it remains the earliest known recording of Lennon. The three-inch reel includes Lennon’s performances of two songs; “Puttin’ on the Style,” a No. 1 hit at the time for Lonnie Donegan, and “Baby Let’s Play House,” an Arthur Gunter song made popular by Elvis Presley. In 1965 Lennon used a line from the Gunter song – “I’d rather see you dead, little girl, than to be with another man”- as the opening line of his own “Run for Your Life”. In 1963, Molyneux offered the tape to Lennon, through Ringo Starr. But Lennon never responded, so Molyneux put the tape in a vault. Original publish date: July 12, 2015

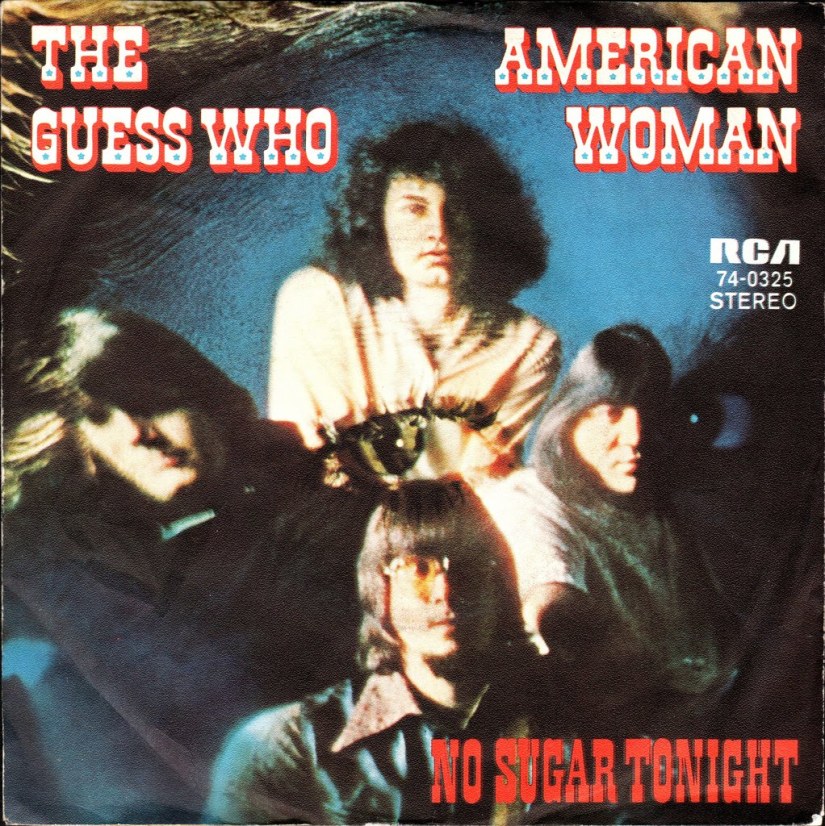

Original publish date: July 12, 2015 Despite it’s popularity and Patriotic sounding title, “American Woman” posed a problem for the Nixon family and more importantly, the Nixon White House. The song was viewed, rightly or wrongly, as as war protest anthem and this was not your ordinary White House garden party. It was a royal reception for England’s Prince Charles and Princess Anne, who were guests at the White House. No doubt the fact that the band was from Canada, a British territory ruled by the Royal guest’s mother, made perfect sense and sealed the deal.

Despite it’s popularity and Patriotic sounding title, “American Woman” posed a problem for the Nixon family and more importantly, the Nixon White House. The song was viewed, rightly or wrongly, as as war protest anthem and this was not your ordinary White House garden party. It was a royal reception for England’s Prince Charles and Princess Anne, who were guests at the White House. No doubt the fact that the band was from Canada, a British territory ruled by the Royal guest’s mother, made perfect sense and sealed the deal. Cummings went on to say this about about playing The White House: “It was strange. All the guests were white, all the military aides were white in full military dress, and all the people serving food were black. And the way the White House was landscaped it kind of looked like Alabama …before Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. It left a bad taste in my mouth. It was terribly racist and this was 1970. I remember sitting with Edward Lear, heir to the Lear Jet fortune, and Billy Graham’s daughter was there. It was really the so-called upper crust aristocracy of America, very stuffy, boring people…We were told not to play “American Woman” but we did “Hand Me Down World.” We thought we were just as cool for doing it. But we did get a great tour of The White House, though, and (band mate) Leskiw and I spent an hour going through all these rooms and corridors seeing stuff most people don’t get to see.”

Cummings went on to say this about about playing The White House: “It was strange. All the guests were white, all the military aides were white in full military dress, and all the people serving food were black. And the way the White House was landscaped it kind of looked like Alabama …before Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. It left a bad taste in my mouth. It was terribly racist and this was 1970. I remember sitting with Edward Lear, heir to the Lear Jet fortune, and Billy Graham’s daughter was there. It was really the so-called upper crust aristocracy of America, very stuffy, boring people…We were told not to play “American Woman” but we did “Hand Me Down World.” We thought we were just as cool for doing it. But we did get a great tour of The White House, though, and (band mate) Leskiw and I spent an hour going through all these rooms and corridors seeing stuff most people don’t get to see.” Original publish date: July 11, 2016

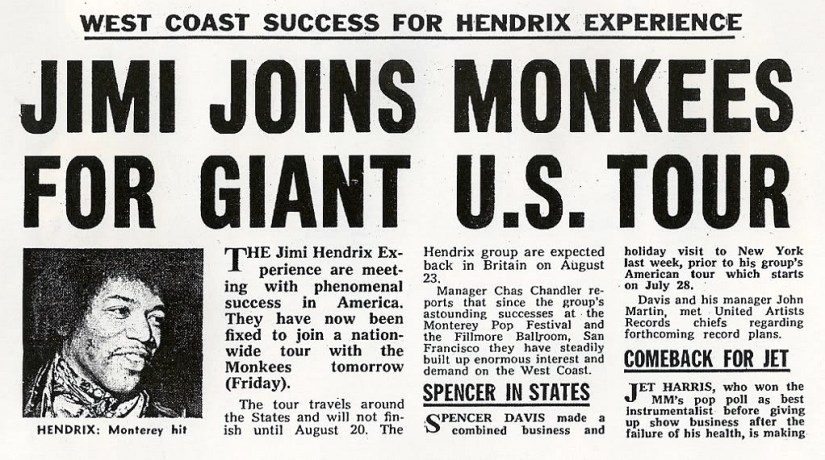

Original publish date: July 11, 2016 Jimi joined the tour on July 8 in Jacksonville, Florida, after The Monkees returned from three gigs in England. Now, imagine being a Monkees-loving teenager wedged into a sweaty, darkened, cram-packed concert hall anticipating the arrival of your favorite TV-pop band. Wearing your Monkees bubblegum machine pins, flipping through your official Monkees trading cards and holding your hand lettered poster professing your love for one Monkee or another. The curtain rises and this new guy Jimi Hendrix storms the stage to melt your face off while playing the guitar with his teeth!

Jimi joined the tour on July 8 in Jacksonville, Florida, after The Monkees returned from three gigs in England. Now, imagine being a Monkees-loving teenager wedged into a sweaty, darkened, cram-packed concert hall anticipating the arrival of your favorite TV-pop band. Wearing your Monkees bubblegum machine pins, flipping through your official Monkees trading cards and holding your hand lettered poster professing your love for one Monkee or another. The curtain rises and this new guy Jimi Hendrix storms the stage to melt your face off while playing the guitar with his teeth!

The Jimi Hendrix Experience experiment lasted just eight of the 29 scheduled tour dates. After only a few gigs, Hendrix grew tired of the “We want the Monkees” chant that met his every performance. Matters came to a head a few days later as the Monkees played a trio of dates in New York. On Sunday July 16, 1967, Jimi flipped off the audience at Forest Hills Stadium in Queens, threw down his guitar and walked off stage, leaving Monkeemania forever in his wake. After all, “Purple Haze” and Are You Experienced? were climbing the American charts, and it was time for him play for audiences who wanted to see him. He asked to be let out of his contract, and he and the Monkees amicably parted ways.

The Jimi Hendrix Experience experiment lasted just eight of the 29 scheduled tour dates. After only a few gigs, Hendrix grew tired of the “We want the Monkees” chant that met his every performance. Matters came to a head a few days later as the Monkees played a trio of dates in New York. On Sunday July 16, 1967, Jimi flipped off the audience at Forest Hills Stadium in Queens, threw down his guitar and walked off stage, leaving Monkeemania forever in his wake. After all, “Purple Haze” and Are You Experienced? were climbing the American charts, and it was time for him play for audiences who wanted to see him. He asked to be let out of his contract, and he and the Monkees amicably parted ways.