Originally published in 2008, this article was reprinted on December 5, 2024. https://weeklyview.net/2024/12/05/irvingtons-disney-prince-bill-shirley-2/

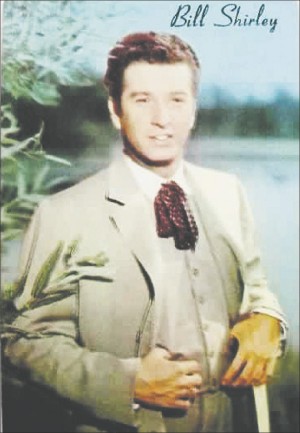

During World War II through the I Like Ike years in America, Irvington had its own representative in Tinseltown. Irvingtonian Bill Shirley made fifteen movies starting in 1941 starring alongside Hollywood luminaries like John Wayne, Abbott and Costello, Ward Bond, and the beautiful Audrey Hepburn. Bill played the part of legendary American songwriter Stephen Foster of “”Swanee River” fame and worked with the great Walt Disney as the voice of Prince Phillip in the 1959 Disney classic Sleeping Beauty.

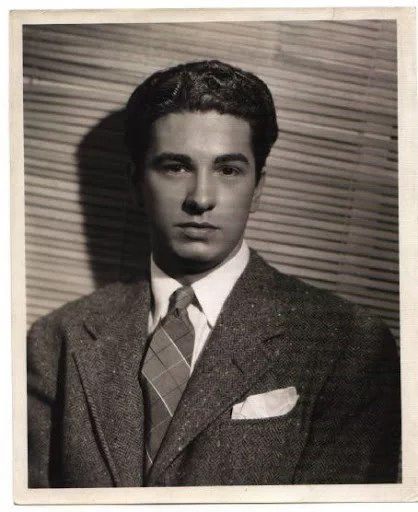

Bill Shirley was born in Irvington on July 6, 1921, and attended George Washington Julian School number 57. From his earliest days, Bill Shirley had a natural talent for singing and acting. He would spend his afternoons daydreaming about becoming a star in Hollywood, and his weekends were spent watching his idols on the big screen at the Irving Theatre, located to this day on Washington Street between the intersection of Ritter and Johnson Streets. By the tender age of 7, blessed with a beautiful singing voice, Bill had the rare honor of singing at the Easter sunrise services held annually from 1929 to 1938 on Monument Circle until age 16. Bill gained his acting abilities while performing in musicals and plays at the Irvington Playhouse and Civic Children’s Theater.

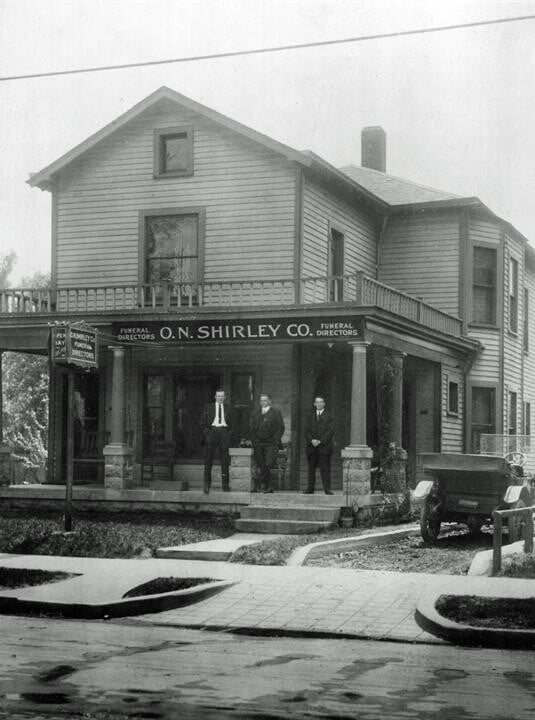

Bill’s father Ottie N. Shirley, along with his uncles Luther and Arley Shirley, formed the Shirley Brothers Funeral Home located at 2755 East Washington St. Bill lived with his family in their home at 5377 East Washington Street until he graduated from Shortridge High School at the age of 18. Immediately after Bill graduated, the family home was remodeled and opened as Irving Hill Chapel, part of the Shirley Brothers mortuary. As soon as Bill completed his studies at Shortridge, his mother packed up their bags and headed for Hollywood. She very wisely hooked Bill up with a voice coach in Los Angeles and almost immediately began to see results. His good looks, along with his mannish voice and natural acting ability, landed Bill a seven-year contract with Republic Pictures at the improbable age of 19. Bill made his first film in early 1941, a musical titled Rookies on Parade starring Bing’s brother Bob Crosby in the lead role. Within a year of arriving in Hollywood, Bill Shirley was cast in seven films for Republic Studios including the John Wayne war film Flying Tigers in 1942. Bill also appeared with one of his childhood idols, Roy Acuff in the 1942 film Hi, Neighbor shot at the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville, Tenn. His other films for Republic included Sailors on Leave and Doctors Don’t Tell in 1941, Ice Capades Review in 1942, Three Little Sisters in 1944, and Oh, You Beautiful Doll in 1949. Bill was uncredited in the film but sang the opening theme for Dancing in the Dark in 1949.

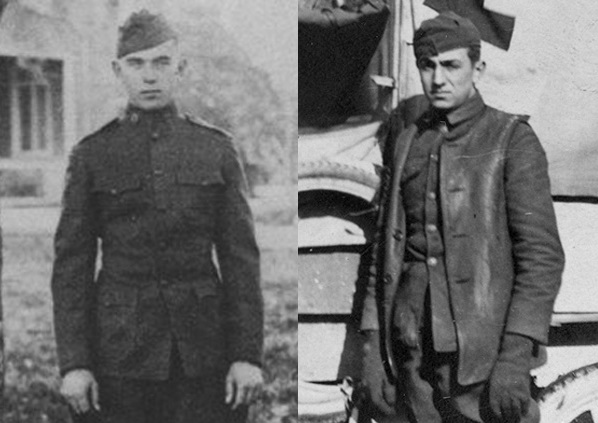

In the summer of 1942, Shirley joined the Army. When he returned at the close of the war, Bill found it hard to pick up his movie career where he had left off. He found a home as a radio announcer in Los Angeles but yearned to return to the big screen. He kept his acting skills sharp by performing on stage in the Hollywood area. He caught a break in 1947 when he was hired to dub the singing of actor Mark Stevens who was starring as Joe Howard, the man who invented kissing, in the entirely forgettable film I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now. This voice-over work came back to haunt him later in his career.

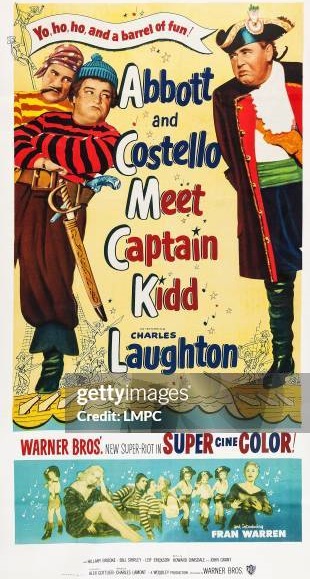

His next big break would come in 1952 when he landed a lead role as Bruce Martingale alongside the comedy team of Abbott & Costello and shared the screen with Academy Award-nominated British actor Charles Laughton in the Warner Brothers film Abbott & Costello Meet Captain Kidd. The critics hated it but the audiences loved this campy film.

Bill landed the role of historic southern songwriter Stephen Foster in the 1952 film I Dream of Jeannie. He returned to Republic Pictures in 1953 to make the film Sweethearts on Parade. In this role, Shirley, along with co-star Ray Middleton, were being touted as Republic’s answer to the Bob Hope and Bing Crosby duo. It didn’t work. It was a critical and box office disappointment. Today the film is most remembered for the staggering 26 different songs in the film. Bill was a winning contestant on Arthur Godfrey’s “Talent Scouts” TV show which ran from 1948 to 1958. “Talent Scouts” was the highest rated TV show in America and was responsible for discovering stars like Tony Bennett, Lenny Bruce, Jonathan Winters, Connie Francis, and Don Knotts. Bill’s winning accomplishment is notable when you consider that Elvis Presley and Buddy Holly auditioned but were not chosen to appear on the show. It would take Bill six years before he made another film. But it was worth the wait.

In 1959, Bill Shirley made the film appearance he is most remembered for by today’s fans when he appeared as the voice of Prince Phillip in Walt Disney Pictures’ Sleeping Beauty. It was an impressive feat considering that he was one of only three lead voices in the entire film. The film would take nearly an entire decade to produce. The story work began in 1951, the voices were recorded in 1952 and the animation production began in 1953 and did not conclude until 1958 with the musical score recorded in 1957. During the original release on January 29, 1959, the film was considered a box office bust, returning only one-half of the Disney Studios’ investment of $6 million. It was widely criticized as slow-paced with little character development. Time has been much kinder to the film and today’s Disney fans and critics alike hail it as one of the best animated films ever made with successful releases in 20 foreign countries. To date the film has grossed nearly $500 million, placing it in the top 30 highest-grossing films of all time.

In 1959, Bill Shirley made the film appearance he is most remembered for by today’s fans when he appeared as the voice of Prince Phillip in Walt Disney Pictures’ Sleeping Beauty. It was an impressive feat considering that he was one of only three lead voices in the entire film. The film would take nearly a decade to produce. The story work began in 1951, the voices were recorded in 1952 and the animation production began in 1953 and did not conclude until 1958 with the musical score recorded in 1957. During the original release on January 29, 1959, the film was considered a box office bust, returning only one-half of the Disney Studios’ investment of $6 million. It was widely criticized as slow-paced with little character development. Time has been much kinder to the film and today’s Disney fans and critics alike hail it as one of the best animated films ever made with successful releases in 20 foreign countries. To date the film has grossed nearly $500 million, placing it in the top 30 highest-grossing films of all time.

Bill Shirley died of lung cancer on August 27, 1989, in Los Angeles, California. He is buried in Crown Hill Cemetery. By the way, what is the trivia question attached to Irvington’s Bill Shirley? Prince Phillip was the first of the Disney Princes to have a first name. Cinderella’s and Snow White’s previous princes had gone nameless. Bill Shirley’s name may be all but forgotten by most of Indy’s eastsiders, but I assure you that not only has he attained a lasting measure of fame in the film industry, but he has also been immortalized in a way that not even his wildest dreams could have predicted. You see, Bill Shirley appeared in the 1953 “Mother’s Cookies” baseball-style trading card set of up-and-coming movie stars. He’s card # 33 out of the 63 card set of these premium cards that were given away in packs of Mothers Cookies sold in the Oakland/San Francisco region. The card is pretty rare and if you can find it at all, it’ll cost you about $25.

Bill Shirley’s Grave at Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis, Indiana.

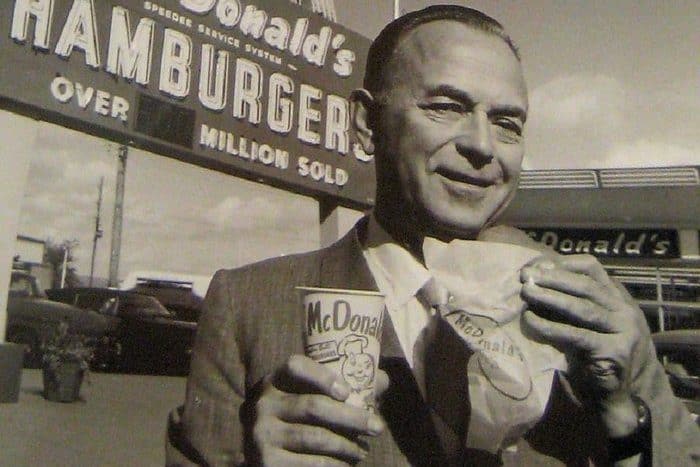

By this time, Ray Kroc was relegated to the sidelines serving in a largely ceremonial role as McDonald’s “senior chairman”. Kroc had given up day-to-day operations of McDonald’s in 1974. Ironically, the same year he bought the San Diego Padres baseball team. The Padres were scheduled to move to Washington, D.C., after the 1973 season. Legend claims that the idea to buy the team formulated in Kroc’s mind while he was reading a newspaper on his private jet. Kroc, a life-long baseball fan who was once foiled in an attempt to buy his hometown Chicago Cubs, turned to his wife Joan and said: “I think I want to buy the San Diego Padres.” Her response: “Why would you want to buy a monastery?” Five years later, frustrated with the team’s performance and league restrictions, Kroc turned the team over to his son-in-law, Ballard Smith. “There’s more future in hamburgers than baseball,” Kroc said. Ray Kroc died on January 14, 1984 and the San Diego Padres won the N.L. pennant that same year (They lost in the World Series to the Detroit Tiger 4 games to 1).

By this time, Ray Kroc was relegated to the sidelines serving in a largely ceremonial role as McDonald’s “senior chairman”. Kroc had given up day-to-day operations of McDonald’s in 1974. Ironically, the same year he bought the San Diego Padres baseball team. The Padres were scheduled to move to Washington, D.C., after the 1973 season. Legend claims that the idea to buy the team formulated in Kroc’s mind while he was reading a newspaper on his private jet. Kroc, a life-long baseball fan who was once foiled in an attempt to buy his hometown Chicago Cubs, turned to his wife Joan and said: “I think I want to buy the San Diego Padres.” Her response: “Why would you want to buy a monastery?” Five years later, frustrated with the team’s performance and league restrictions, Kroc turned the team over to his son-in-law, Ballard Smith. “There’s more future in hamburgers than baseball,” Kroc said. Ray Kroc died on January 14, 1984 and the San Diego Padres won the N.L. pennant that same year (They lost in the World Series to the Detroit Tiger 4 games to 1). By the 1980s, Disney was a corporation that seemed to be creatively exhausted. The entertainment giant was seriously out of touch with what consumers wanted to buy, what moviegoers wanted to see. McDonald’s had introduced their wildly popular “Happy Meal” nationwide in 1979. Disney saw an opportunity for revival by proposing the idea of adding Disney toys and merchandising to Happy Meals. In 1987, the first Disney Happy Meal debuted, offering toys and prizes from familiar characters like Cinderella, The Sword In The Stone, Mickey Mouse, Aladdin, Simba, Finding Nemo, Jungle Book, 101 Dalmatians, The Lion King and other classics. For a time, changing food habits, mismanagement and failure to recognize trends, placed the Disney corporation in an exposed position. Rumors circulated that the Mouse was on the brink of being swallowed up by Mickey D’s.

By the 1980s, Disney was a corporation that seemed to be creatively exhausted. The entertainment giant was seriously out of touch with what consumers wanted to buy, what moviegoers wanted to see. McDonald’s had introduced their wildly popular “Happy Meal” nationwide in 1979. Disney saw an opportunity for revival by proposing the idea of adding Disney toys and merchandising to Happy Meals. In 1987, the first Disney Happy Meal debuted, offering toys and prizes from familiar characters like Cinderella, The Sword In The Stone, Mickey Mouse, Aladdin, Simba, Finding Nemo, Jungle Book, 101 Dalmatians, The Lion King and other classics. For a time, changing food habits, mismanagement and failure to recognize trends, placed the Disney corporation in an exposed position. Rumors circulated that the Mouse was on the brink of being swallowed up by Mickey D’s.

Additionally, there once was a McDonald’s at downtown Disney (before it became Disney Springs). At the Magic Kingdom, visitors could munch on french fries at the Village Fire Shoppe. At Disney’s Hollywood Studios, McDonald’s sponsored Fairfax Fries at the Sunset Ranch March. Fairfax is a reference to the street where the famous Los Angeles Farmers Market (the inspiration for the Sunset Ranch Market) is located. At Epcot, on the World Showcase promenade, is the Refreshment Port where sometimes international cast members from Canada would bring Canadian Smarties (similar to M&Ms) for the food and beverage location to make a Smarties McFlurry. The exclusive contract with Disney did not allow McDonald’s to tie in with blockbuster movies such as the Star Wars franchise even though movie studios would have preferred the tie in since McDonald’s had a higher profile and market share.

Additionally, there once was a McDonald’s at downtown Disney (before it became Disney Springs). At the Magic Kingdom, visitors could munch on french fries at the Village Fire Shoppe. At Disney’s Hollywood Studios, McDonald’s sponsored Fairfax Fries at the Sunset Ranch March. Fairfax is a reference to the street where the famous Los Angeles Farmers Market (the inspiration for the Sunset Ranch Market) is located. At Epcot, on the World Showcase promenade, is the Refreshment Port where sometimes international cast members from Canada would bring Canadian Smarties (similar to M&Ms) for the food and beverage location to make a Smarties McFlurry. The exclusive contract with Disney did not allow McDonald’s to tie in with blockbuster movies such as the Star Wars franchise even though movie studios would have preferred the tie in since McDonald’s had a higher profile and market share.

During his lifetime, Walt Disney received 59 Academy Award nominations, including 22 awards: both totals are records. Walt Disney’s net worth was equal to roughly $1 billion at the time of his death in 1966 (after adjusting for inflation). At the time of his death, Disney’s various assets were worth $100-$150 million in 1966 dollars which is the same as $750 million-$1.1 billion today. By the time of Kroc’s death in 1984, his net worth was $600 million. That’s the same as $1.4 billion after adjusting for inflation. One can only imagine how the pop culture landscape might have changed back in 1955 if those two former ambulance corps buddies had formed a partnership. But wait, would that make it Mickey D’s Mouse?

During his lifetime, Walt Disney received 59 Academy Award nominations, including 22 awards: both totals are records. Walt Disney’s net worth was equal to roughly $1 billion at the time of his death in 1966 (after adjusting for inflation). At the time of his death, Disney’s various assets were worth $100-$150 million in 1966 dollars which is the same as $750 million-$1.1 billion today. By the time of Kroc’s death in 1984, his net worth was $600 million. That’s the same as $1.4 billion after adjusting for inflation. One can only imagine how the pop culture landscape might have changed back in 1955 if those two former ambulance corps buddies had formed a partnership. But wait, would that make it Mickey D’s Mouse?

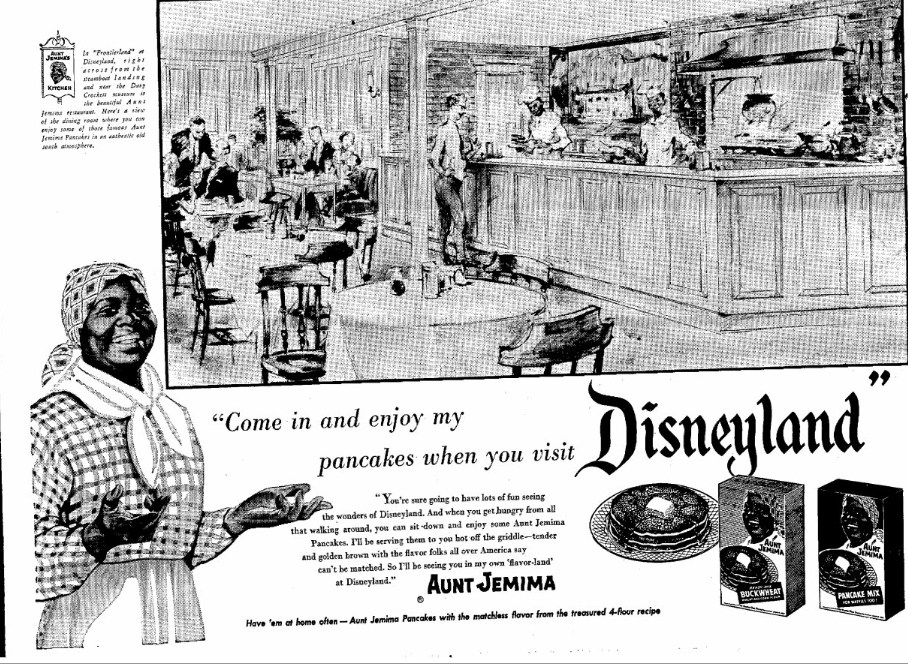

From there, well, nobody knows. For the answer, you need look no further than the fact that there are no McDonald’s at Disney. It should be noted that there were SOME franchise restaurants in Disneyland during those first first years. They included the Aunt Jemima pancake and waffle house in Frontierland and the Chicken of the Sea Pirate Ship in Fantasyland.

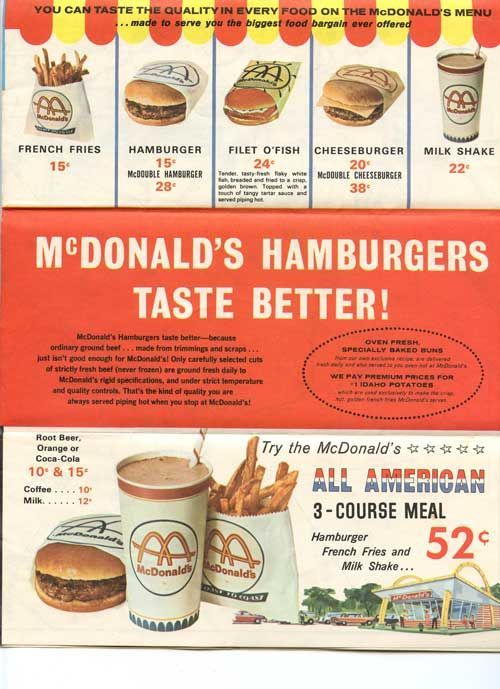

From there, well, nobody knows. For the answer, you need look no further than the fact that there are no McDonald’s at Disney. It should be noted that there were SOME franchise restaurants in Disneyland during those first first years. They included the Aunt Jemima pancake and waffle house in Frontierland and the Chicken of the Sea Pirate Ship in Fantasyland. To his dying day, Ray Kroc insisted that the reason the “world’s first McDonald’s” was not featured inside Disneyland at the park’s July 17, 1955 grand opening was because the head of concessions had tried to force Ray to raise the price of his french fries by a nickle (from 10 cents to 15 cents) for the Disneyland crowd. Kroc, the man in charge of McDonald’s franchising, believed that he was being charged a franchise fee by virtue of Walt Disney Productions tacking on a concessionaire’s fee. Kroc, the consummate businessman, said he wasn’t about to give away 1/3 of his profits while gouging his customers. Great story, but by the time Disneyland debuted, Kroc had only opened one McDonald’s franchise (in Des Plaines, Illinois on April 15, 1955). So he had no loyal customers to offend…yet. Well, no customers within 2,000 miles anyway.

To his dying day, Ray Kroc insisted that the reason the “world’s first McDonald’s” was not featured inside Disneyland at the park’s July 17, 1955 grand opening was because the head of concessions had tried to force Ray to raise the price of his french fries by a nickle (from 10 cents to 15 cents) for the Disneyland crowd. Kroc, the man in charge of McDonald’s franchising, believed that he was being charged a franchise fee by virtue of Walt Disney Productions tacking on a concessionaire’s fee. Kroc, the consummate businessman, said he wasn’t about to give away 1/3 of his profits while gouging his customers. Great story, but by the time Disneyland debuted, Kroc had only opened one McDonald’s franchise (in Des Plaines, Illinois on April 15, 1955). So he had no loyal customers to offend…yet. Well, no customers within 2,000 miles anyway. It is more likely to say that while the executives in charge of Disneyland’s concessions were undoubtedly intrigued by Ray’s “fast food” proposal, “war buddy” or not, Kroc just didn’t have enough experience in the restaurant business to take that gamble. So, despite how Kroc spun the tale to reporters from the 1950s forward, while there was some discussion of putting a McDonald’s inside the theme park, the project never really made it past the talking stage. But Ray Kroc would never let the truth stand in the way of a good story.

It is more likely to say that while the executives in charge of Disneyland’s concessions were undoubtedly intrigued by Ray’s “fast food” proposal, “war buddy” or not, Kroc just didn’t have enough experience in the restaurant business to take that gamble. So, despite how Kroc spun the tale to reporters from the 1950s forward, while there was some discussion of putting a McDonald’s inside the theme park, the project never really made it past the talking stage. But Ray Kroc would never let the truth stand in the way of a good story.

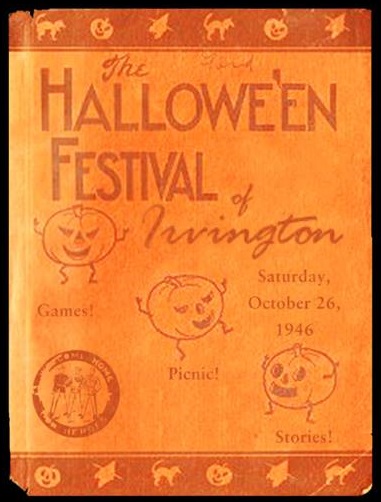

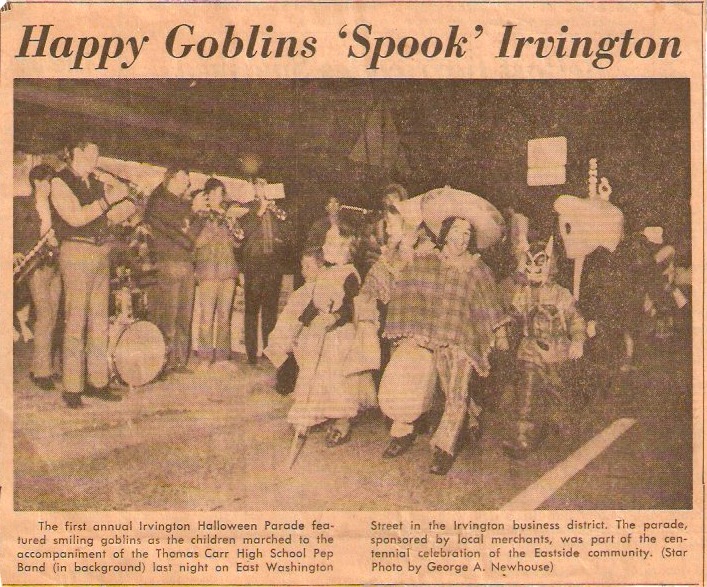

We’ve all heard the stories, legends and rumors surrounding that now legendary first event. It was sponsored by the Walt Disney company featuring costumed characters with a Disney based theme. The Disney folks gave away potentially priceless hand painted film production cels right here on the streets of old Irvington town. Walt Disney himself was seen walking down Audubon with Mickey Mouse at his side. It’s hard to separate fact from fiction nowadays.

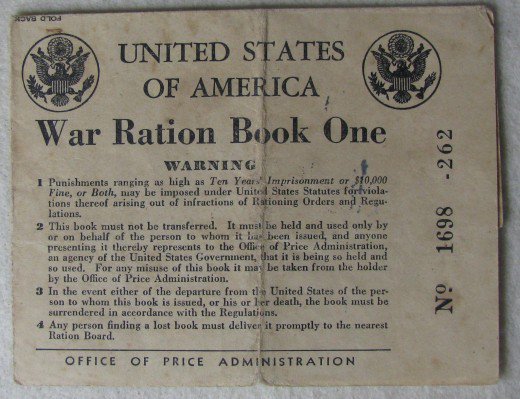

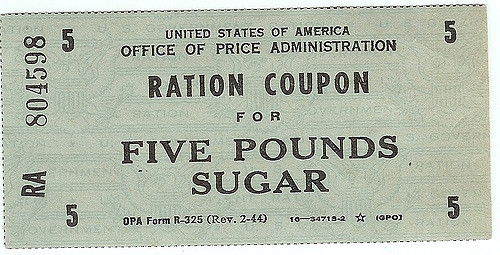

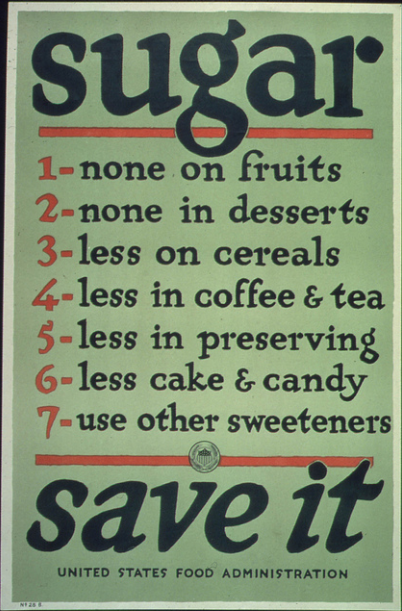

We’ve all heard the stories, legends and rumors surrounding that now legendary first event. It was sponsored by the Walt Disney company featuring costumed characters with a Disney based theme. The Disney folks gave away potentially priceless hand painted film production cels right here on the streets of old Irvington town. Walt Disney himself was seen walking down Audubon with Mickey Mouse at his side. It’s hard to separate fact from fiction nowadays. A week later on May 5, 1942, every United States citizen received their much anticipated “War Ration Book Number One”, good for a 56-week supply of sugar. Initially, each stamp was good for one pound of sugar and could be redeemed over a specified two-week period. Later on, as other items such as coffee and shoes were rationed, each stamp became good for two pounds of sugar over a four-week period. The ration book bore the recipient’s name and could only be used by household members. Stamps had to be torn off in the presence of the grocer. If the book was lost, stolen, or destroyed, an application had to be submitted to the Ration Board for a new copy. If the ration book holder entered the hospital for greater than a 10-day stay, the ration book had to be brought along with them. Talk about your red tape!

A week later on May 5, 1942, every United States citizen received their much anticipated “War Ration Book Number One”, good for a 56-week supply of sugar. Initially, each stamp was good for one pound of sugar and could be redeemed over a specified two-week period. Later on, as other items such as coffee and shoes were rationed, each stamp became good for two pounds of sugar over a four-week period. The ration book bore the recipient’s name and could only be used by household members. Stamps had to be torn off in the presence of the grocer. If the book was lost, stolen, or destroyed, an application had to be submitted to the Ration Board for a new copy. If the ration book holder entered the hospital for greater than a 10-day stay, the ration book had to be brought along with them. Talk about your red tape!

To make matters worse, just because you had a sugar stamp didn’t mean sugar was available for purchase. Shortages occurred often throughout the war, and in early 1945 sugar became nearly impossible to find in any quantity. As Europe was liberated from the grip of Nazi Germany, the United States took on the main responsibility for providing food to those war ravaged countries. On May 1, 1945, the sugar ration for American families was slashed to 15 pounds per year for household use and 15 pounds per year for canning – roughly eight ounces per week per household. Sugar supplies remained scarce and, just as sugar had the distinction of being the first product rationed at the start of the war, sugar was the last product to be rationed after the war. Sugar rationing continued until June of 1947, over six months after the first Irvington Halloween festival in October of 1946.

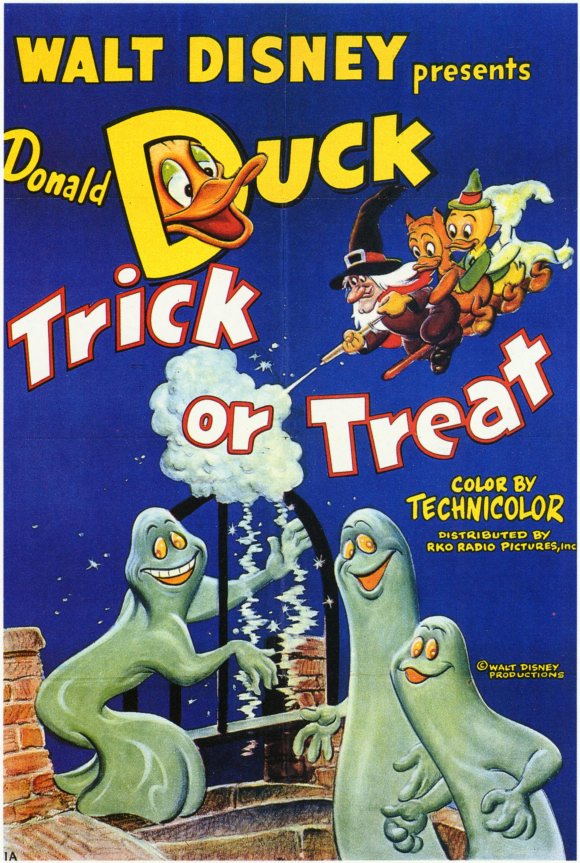

To make matters worse, just because you had a sugar stamp didn’t mean sugar was available for purchase. Shortages occurred often throughout the war, and in early 1945 sugar became nearly impossible to find in any quantity. As Europe was liberated from the grip of Nazi Germany, the United States took on the main responsibility for providing food to those war ravaged countries. On May 1, 1945, the sugar ration for American families was slashed to 15 pounds per year for household use and 15 pounds per year for canning – roughly eight ounces per week per household. Sugar supplies remained scarce and, just as sugar had the distinction of being the first product rationed at the start of the war, sugar was the last product to be rationed after the war. Sugar rationing continued until June of 1947, over six months after the first Irvington Halloween festival in October of 1946. An argument can be made that it was events like the First Irvington Halloween Festival that kicked off the tradition of trick-or-treating as we know it today. Although the Halloween holiday was certainly well known in America before that first Irvington celebration, it was predominantly a holiday for adult costume parties and a chance to cut loose with friends playing party games while consuming hard cider. Early national attention to trick-or-treating in popular culture really began a year later in October of 1947. That’s when the custom of passing out the playful “candy bribes” began to appear in issues of children’s magazines like Jack and Jill and Children’s Activities, and in Halloween episodes of network radio programs like The Baby Snooks Show, The Jack Benny Show and The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet. Trick-or-treating was first depicted in a Peanuts comic strip in 1951, perhaps the image most identified with the children’s holiday in the hearts and minds of baby boomers today. The custom had become firmly established in popular culture by 1952, when Walt Disney debuted his Donald Duck movie “Trick or Treat”, and again when Ozzie and Harriet were besieged by trick-or-treaters on an episode of their popular television show. In 1953, less than a decade after that first festival in Irvington, the tradition of Halloween as a children’s holiday was fully accepted when UNICEF conducted it’s first national children’s charity fund raising campaign centered around trick-or-treaters.

An argument can be made that it was events like the First Irvington Halloween Festival that kicked off the tradition of trick-or-treating as we know it today. Although the Halloween holiday was certainly well known in America before that first Irvington celebration, it was predominantly a holiday for adult costume parties and a chance to cut loose with friends playing party games while consuming hard cider. Early national attention to trick-or-treating in popular culture really began a year later in October of 1947. That’s when the custom of passing out the playful “candy bribes” began to appear in issues of children’s magazines like Jack and Jill and Children’s Activities, and in Halloween episodes of network radio programs like The Baby Snooks Show, The Jack Benny Show and The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet. Trick-or-treating was first depicted in a Peanuts comic strip in 1951, perhaps the image most identified with the children’s holiday in the hearts and minds of baby boomers today. The custom had become firmly established in popular culture by 1952, when Walt Disney debuted his Donald Duck movie “Trick or Treat”, and again when Ozzie and Harriet were besieged by trick-or-treaters on an episode of their popular television show. In 1953, less than a decade after that first festival in Irvington, the tradition of Halloween as a children’s holiday was fully accepted when UNICEF conducted it’s first national children’s charity fund raising campaign centered around trick-or-treaters. Most of this column’s readers are aware that part of my passion for history revolves around collecting, cataloging, displaying and observing antiques and collectibles. There exists in the collecting world a strong group of enthusiasts devoted to the pursuit and preservation of Halloween memorabilia of all types. Costumes, decorations, photographs, publications and postcards in particular. The origins of Halloween as we now know it might best be traced in the postcards issued to celebrate the tradition. The thousands of Halloween postcards produced between the turn of the 20th century and the 1920s commonly show costumed children, but do not depict trick-or-treating. It is believed that the pranks associated with early Halloween were perpetrated by unattended children left to their own devices while their parents caroused and partied without them. Some have characterized Halloween trick-or-treating as an adult invention to curtail vandalism previously associated with the holiday. Halloween was not widely accepted and many adults, as reported in newspapers from the 1930s and 1940s, typically saw it as a form of extortion, with reactions ranging from bemused indulgence to anger. Sometimes, even the children protested. As late as Halloween of 1948, members of the Madison Square Boys Club in New York City carried a parade banner that read “American Boys Don’t Beg.” Times have certainly changed since that first Halloween festival 65 years ago.

Most of this column’s readers are aware that part of my passion for history revolves around collecting, cataloging, displaying and observing antiques and collectibles. There exists in the collecting world a strong group of enthusiasts devoted to the pursuit and preservation of Halloween memorabilia of all types. Costumes, decorations, photographs, publications and postcards in particular. The origins of Halloween as we now know it might best be traced in the postcards issued to celebrate the tradition. The thousands of Halloween postcards produced between the turn of the 20th century and the 1920s commonly show costumed children, but do not depict trick-or-treating. It is believed that the pranks associated with early Halloween were perpetrated by unattended children left to their own devices while their parents caroused and partied without them. Some have characterized Halloween trick-or-treating as an adult invention to curtail vandalism previously associated with the holiday. Halloween was not widely accepted and many adults, as reported in newspapers from the 1930s and 1940s, typically saw it as a form of extortion, with reactions ranging from bemused indulgence to anger. Sometimes, even the children protested. As late as Halloween of 1948, members of the Madison Square Boys Club in New York City carried a parade banner that read “American Boys Don’t Beg.” Times have certainly changed since that first Halloween festival 65 years ago. A 2005 study by the National Confectioners Association reported that 80 percent of American households gave out candy to trick-or-treaters, and that 93 percent of children, teenagers, and young adults planned to either venture out trick-or-treating or to participate in other Halloween associated activities. In 2008, Halloween candy, costumes and other related products accounted for $5.77 billion in revenue. An estimated $2 billion worth of candy will be passed out during this Halloween season and one study claims that “an average Jack-O-Lantern bucket carries about 250 pieces of candy amounting to about 9,000 calories and containing three pounds of sugar.” Yes, 65-years ago, Halloween looked quite different than it does today. Next week, doorbells all over Irvington will ring, doors will be opened and wide-eyed gaggles of eager children will unanimously cry out “Trick-or-Treat” from Oak Avenue to Pleasant Run Parkway.

A 2005 study by the National Confectioners Association reported that 80 percent of American households gave out candy to trick-or-treaters, and that 93 percent of children, teenagers, and young adults planned to either venture out trick-or-treating or to participate in other Halloween associated activities. In 2008, Halloween candy, costumes and other related products accounted for $5.77 billion in revenue. An estimated $2 billion worth of candy will be passed out during this Halloween season and one study claims that “an average Jack-O-Lantern bucket carries about 250 pieces of candy amounting to about 9,000 calories and containing three pounds of sugar.” Yes, 65-years ago, Halloween looked quite different than it does today. Next week, doorbells all over Irvington will ring, doors will be opened and wide-eyed gaggles of eager children will unanimously cry out “Trick-or-Treat” from Oak Avenue to Pleasant Run Parkway. Costumed kids will be rewarded for their efforts with all sorts of tribute in the form of coins, nuts, popcorn balls, fruit, cookies, cakes, and toys. As a casual observer born long after that first Irvington Halloween Festival and an active participant in the festivities that will begin next week, I’m glad that our Irvington forefathers skirted government regulations all those years ago. In fact, as a fan of all things Irvington, I’d go so far as to say that this community has played a big part in the Halloween holiday as we know it today. Because, grammar notwithstanding, nobody does Halloween like Irvington do.

Costumed kids will be rewarded for their efforts with all sorts of tribute in the form of coins, nuts, popcorn balls, fruit, cookies, cakes, and toys. As a casual observer born long after that first Irvington Halloween Festival and an active participant in the festivities that will begin next week, I’m glad that our Irvington forefathers skirted government regulations all those years ago. In fact, as a fan of all things Irvington, I’d go so far as to say that this community has played a big part in the Halloween holiday as we know it today. Because, grammar notwithstanding, nobody does Halloween like Irvington do. Original publish date: October 29, 2014

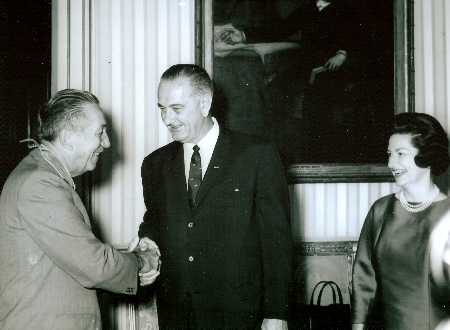

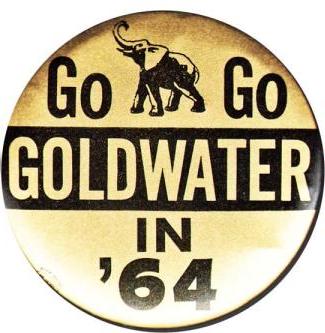

Original publish date: October 29, 2014 Back in Los Angeles, Walt told his daughter that he had worn the small button openly and that he had worn the larger “Go Go Goldwater” button on the underside of his lapel. He explained this double placement as “So if anyone said anything about it [the small button], I’d flash this [the larger button]… as if to say, ‘which one do you prefer I wear?’ Wearing an opponent’s button visible to LBJ would seem to have been a slap in the President’s face, a rude gesture difficult to reconcile with the Walt Disney legend.

Back in Los Angeles, Walt told his daughter that he had worn the small button openly and that he had worn the larger “Go Go Goldwater” button on the underside of his lapel. He explained this double placement as “So if anyone said anything about it [the small button], I’d flash this [the larger button]… as if to say, ‘which one do you prefer I wear?’ Wearing an opponent’s button visible to LBJ would seem to have been a slap in the President’s face, a rude gesture difficult to reconcile with the Walt Disney legend.