Original publish date February 22, 2024. https://weeklyview.net/2024/02/22/the-breathalyzer/

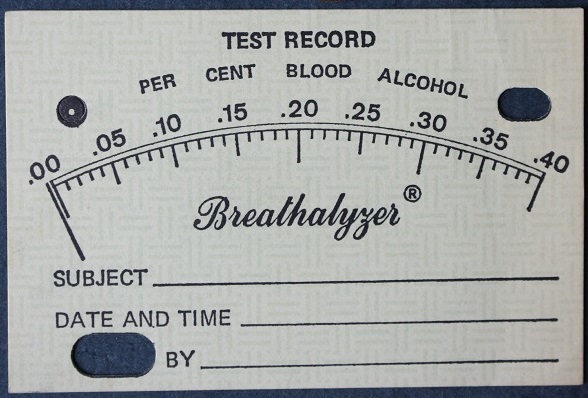

Recently, I found myself at an antique show rummaging through a small box of paper, not unfamiliar territory for me. The usual: postcards, coupons, ads, snapshot photos. Then my fingers danced past a small greenish-colored slip of paper with a frozen gauge chart numbered .00 to .40 and a pair of machine-cut holes in the corners. Titled “Breathalyzer” it was identified as a “Test Meter” to measure “Per Cent Blood Alcohol” with an unused 3-line identifier at the bottom for the “Subject” name, “Date and Time”, and name of the person administering the test. Okay, we all know what it means (some more than others) and if we are smart (or lucky) we have managed to avoid these at all costs in our lifetimes.

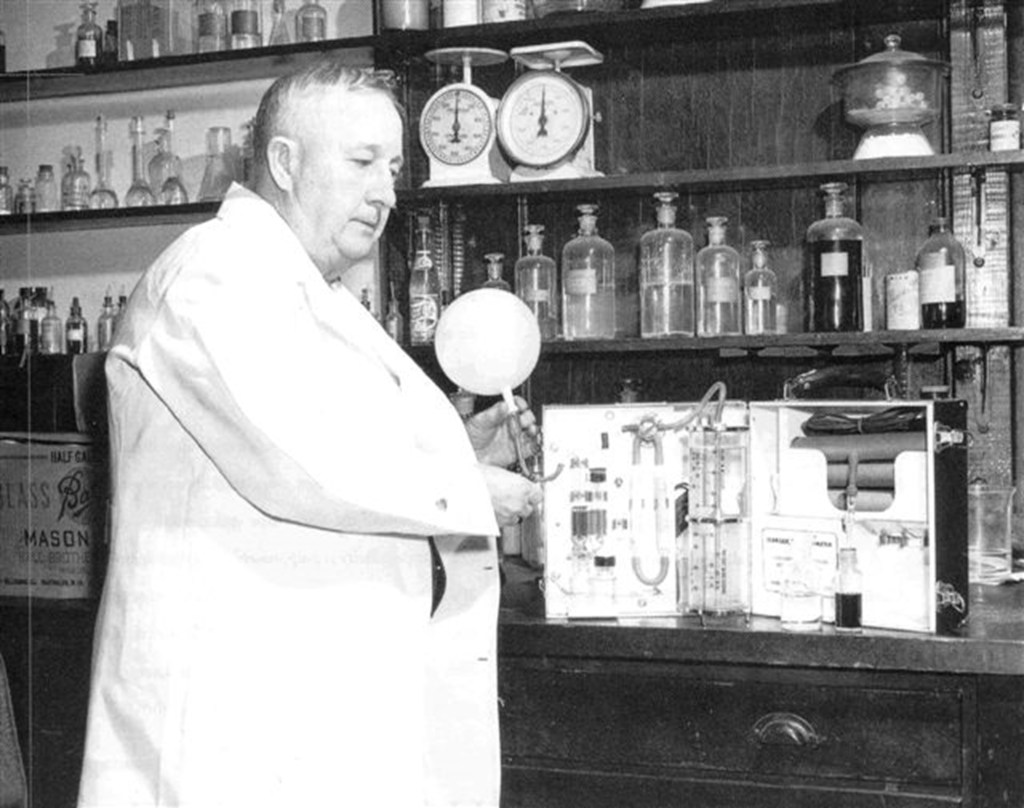

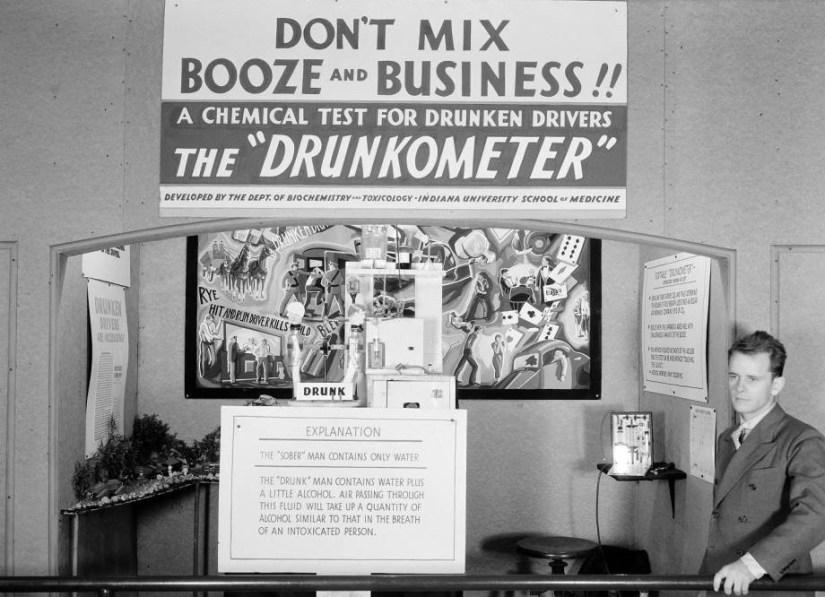

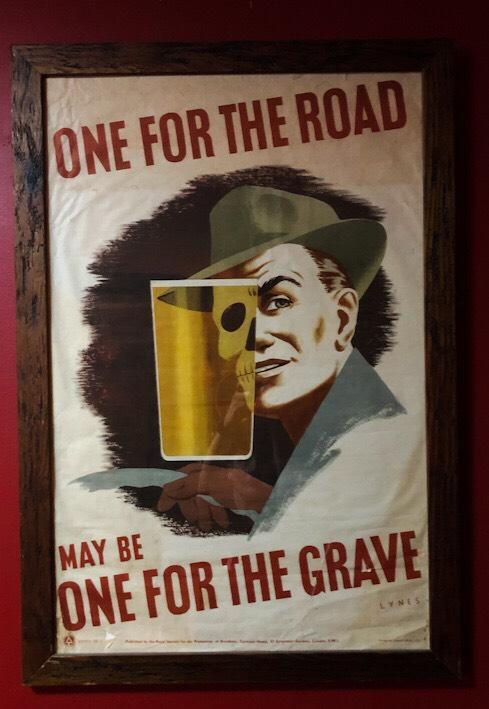

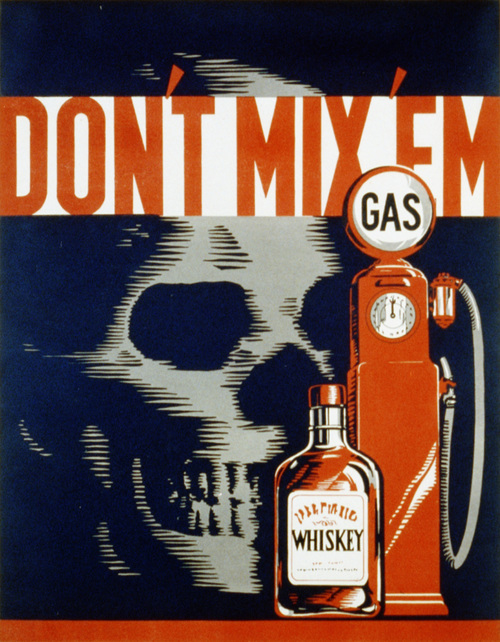

But did you know that the “Breathalyzer” instrument, known around the world as the “Breath of Death”, the “Intoxalock”, or the “Booze Kazoo”, was invented in Indiana? In 1931, a 41-year-old toxicology professor at Indiana University named Rolla Harger invented the first practical roadside breath-testing device called the Drunkometer. He was awarded a patent for it in 1936. The Drunkometer collected a sample of the motorist’s breath when the driver blew directly into a balloon attached to the machine. The breath sample was then pumped through an acidified potassium permanganate solution and if there was alcohol in the sample, the solution changed color. The greater the color change, the more alcohol there was present in the breath.

In 1922, Harger became an assistant professor at Indiana University School of Medicine in the newly formed Department of Biochemistry and Pharmacology. He served as the department chairman from 1933 to 1956 and worked continuously in the department until 1960. However, the bulky Drunkometer proved impractical and unportable. The test required the suspected impaired driver to effectively inflate a balloon (a challenging task for some drunk or sober), which was then taken to the machine at police headquarters. This time-consuming, awkward process depended on the visual skills of the technician analyzing the sample-an Achilles heel that defense lawyers were often successful contesting. The Drunkometer eventually fell out of favor with police officers who saw it as complicated and unreliable. Police instead preferred to administer roadside dexterity tests to determine intoxication.

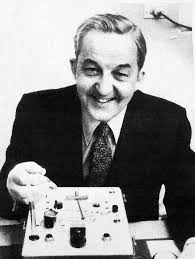

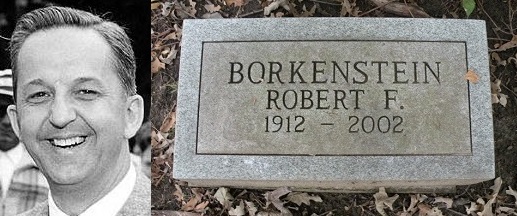

Enter Robert Frank Borkenstein. Born August 31, 1912, in Fort Wayne, Borkenstein was a natural-born teacher, researcher, and inventor. Borkenstein was a product of the Great Depression, and like many young Hoosiers of that era, he was unable to attend college. His first job in Fort Wayne was as a photographic technician, where legend claims his expertise in color film led (at least in part) to the invention of the color camera. While that claim is hard to nail down, what we do know is that his skill and creativity were recognized by the Indiana State Police Criminology Laboratory which hired him in 1936. Borkenstein quickly rose through the ranks, he went from working as a clerk to Captain in charge of Laboratory Services to Director of the State Police Criminological Laboratory, one of the first state police laboratories in the US. During his time with the department, Borkenstein helped perfect the use of photography in law enforcement and worked extensively on developing the polygraph, or lie detector. He administered more than 15,000 tests before his retirement in the late 1980s.

Also while with the department, Borkenstein developed a close professional relationship with IU Professor Rolla N. Harger who was still working to improve his Drunkometer. In the 1950s, Borkenstein attended Indiana University on a part-time basis, eventually earning his Bachelor of Arts in Forensic Science. In February of 1954, IPD Lieutenant Borkenstein, Director of the State police laboratory, developed his first working model of the Breathalyzer (an amalgam of “breath, alcohol and analyze”) in the partially dirt-floored basement of his small Indianapolis home at 6441 Broadway near Broad Ripple. His machine was more compact, easier to operate, and consistently produced reliable results when measuring blood alcohol content. The Breathalyzer substituted a rubber hose for the balloon and featured an automatic internal device to gauge the color changes previously determined by the naked eye. Borkenstein’s Breathalyzer was an inexpensive way to test intoxication and meant that BAC (blood alcohol content) could be quickly collected and analyzed for use as evidence. Upon graduation from IU, Borkenstein retired from the State Police and joined IU as Chairman of the newly-formed Department of Police Administration.

Robert Borkenstein, a convivial fellow known as “Bob” to friends, family, and colleagues, enjoyed listening to Gilbert and Sullivan, entertaining visitors, and serving drinks to his friends. According to one account, ironically Bob “exhibited a Catholic taste in wines and spirits”. But Bob insisted on one rule for himself and anyone consuming alcohol in his presence: No drinking and driving! This, even though he supervised a study, paid for by the liquor industry, that suggested that “the relaxing effect of having drunk less than two ounces of alcohol might produce a slightly better driver than one who had none”.

At I.U., Borkenstein was well-liked and known for his generosity to younger colleagues. He was also a Francophile who traveled extensively to Paris and other parts of France, incorporating the French language into much of his work. Another gadget Borkenstein invented was a coin-operated Breathalyser for use in bars. The idea is that when a customer drops a coin it causes a straw to pop up. When the straw is blown into, a reading of .04 or less would produce a message: “Be a safe driver.” Between .05 and .09, the machine blinked and advised: “Be a good walker.” At .10 or higher, it sounded a small alarm and warned: “You’re a passenger.”

He later became chairman of IU’s Forensic Studies Department and director of the university’s Centre for Studies of Law in Action. The class he established on alcohol and highway safety became a national standard in the United States for forensic science, law enforcement, and criminal justice professionals. Today, it is officially known as the “Robert F. Borkenstein Course on Alcohol and Highway Safety: Testing, Research, and Litigation”, more simply known as the “Borky”. In light of his achievements, Borkenstein was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Science by Wittenberg University in 1963 and an Honorary LL.D. from Indiana University in 1987. In March 1987 Borkenstein retired, though he continued to hold emeritus titles as both a professor and Director of the Center for Studies of Law in Action and was inducted into the Safety and Health Hall of Fame International in 1988. Borkenstein’s mentor Dr. Rolla Neil Harger died on August 8, 1983, in Indianapolis and is buried in Crown Hill Cemetery. Borkenstein’s papers are held at the Indiana University Archives in the Herman B Wells Library in Bloomington, IN.

Fort Wayne, Allen County, Indiana.

In 1938 Borkenstein married Marjorie K. Buchanan, a children’s book author who died in December 1998. The couple had no children. Robert Borkenstein died on August 10, 2002, at the age of 89. Borkenstein held the Breathalyzer patent for most of his life, finally selling it to the Colorado firm that markets it today. Although the Breathalyzer is no longer the dominant instrument used by police forces to determine alcohol intoxication, its name has entered the vernacular to the extent that it has become a generic name for any breath-testing instrument. Between 1955 and 1999, over 30,000 Breathalyzer units were sold. Without question, Bob Borkenstein’s invention has saved countless lives over the years and has become an irreplaceable tool of the police. And to think, it all started in Indiana.

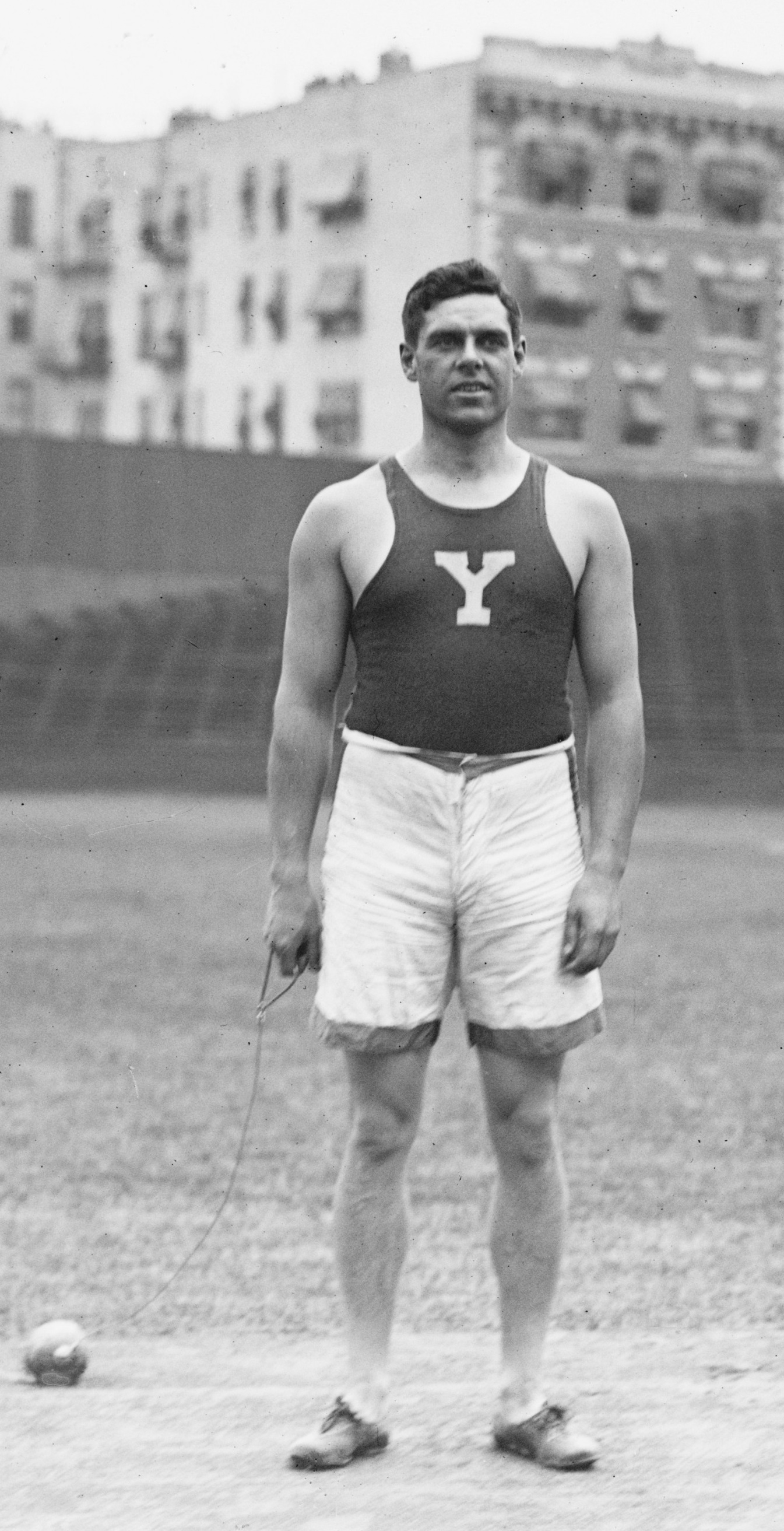

Thorpe played professional football in 1913 as a member of the Indiana-based Pine Village Pros, a team that had a several-season winning streak against local teams during the 1910s. Also that year, Thorpe signed pro contracts to play baseball with the New York Giants and football for the Chicago Cardinals and Canton (Ohio) Bulldogs. The Bulldogs paid Thorpe $ 250 per game ($5,919 today) a huge sum for the time. Overnight, the Bulldogs went from drawing 1,200 fans per game to 8,000. Thorpe was front page news, leading the Bulldogs to league championships in 1916, 1917 and 1919. In 1920, the Bulldogs and 13 other teams formed the APFA (American Professional Football Association) the forerunner of today’s NFL and Thorpe was elected the league’s first president. You might say that Jim Thorpe was a big deal.

Thorpe played professional football in 1913 as a member of the Indiana-based Pine Village Pros, a team that had a several-season winning streak against local teams during the 1910s. Also that year, Thorpe signed pro contracts to play baseball with the New York Giants and football for the Chicago Cardinals and Canton (Ohio) Bulldogs. The Bulldogs paid Thorpe $ 250 per game ($5,919 today) a huge sum for the time. Overnight, the Bulldogs went from drawing 1,200 fans per game to 8,000. Thorpe was front page news, leading the Bulldogs to league championships in 1916, 1917 and 1919. In 1920, the Bulldogs and 13 other teams formed the APFA (American Professional Football Association) the forerunner of today’s NFL and Thorpe was elected the league’s first president. You might say that Jim Thorpe was a big deal.

A total of 17 people died immediately, including 13 players, a coach, a trainer, a student manager and a booster. One member of the team miraculously landed on his feet and was unharmed after being thrown out a window. All the casualties were limited to the team’s railcar. Twenty-nine more players were hospitalized, several of whom suffered crippling injuries that would last the rest of their lives. Further tragedy was averted when several people, led by the “John Purdue Special” brakeman, ran up the track to slow down the second special train that was following 10 minutes behind the first. This heroic action undoubtedly saved many lives by preventing another train wreck. One of the survivors of the wreck was Purdue University President Winthrop E. Stone who remained on the scene to comfort the injured and dying.

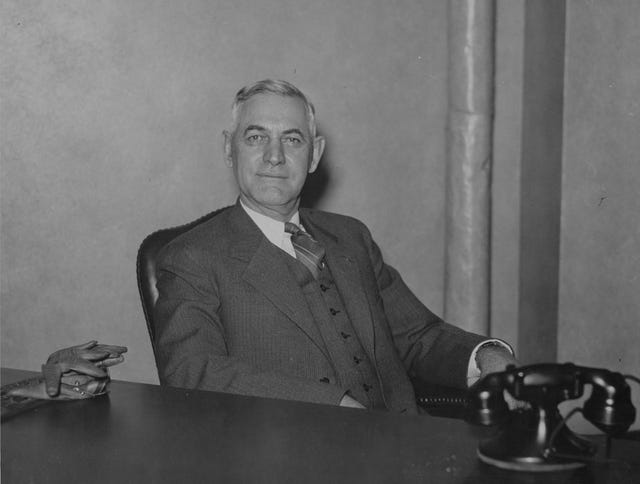

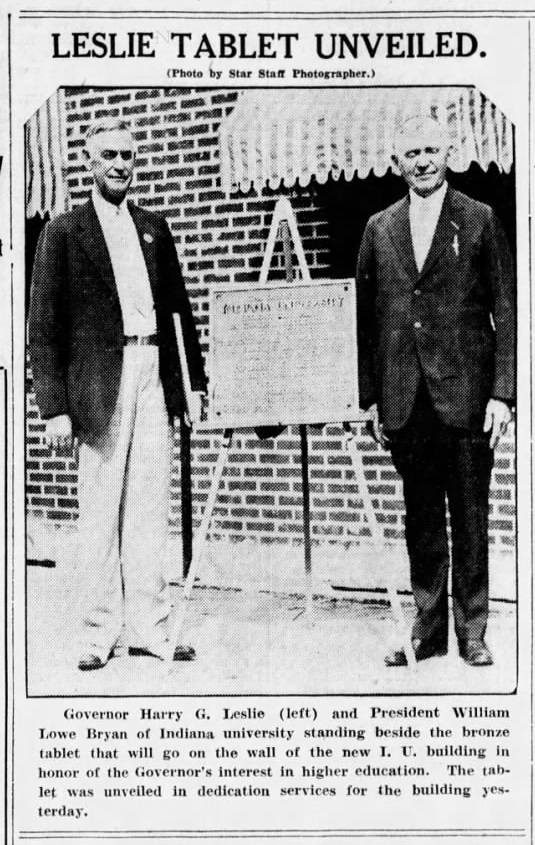

A total of 17 people died immediately, including 13 players, a coach, a trainer, a student manager and a booster. One member of the team miraculously landed on his feet and was unharmed after being thrown out a window. All the casualties were limited to the team’s railcar. Twenty-nine more players were hospitalized, several of whom suffered crippling injuries that would last the rest of their lives. Further tragedy was averted when several people, led by the “John Purdue Special” brakeman, ran up the track to slow down the second special train that was following 10 minutes behind the first. This heroic action undoubtedly saved many lives by preventing another train wreck. One of the survivors of the wreck was Purdue University President Winthrop E. Stone who remained on the scene to comfort the injured and dying. Walter Bailey, a reserve player from New Richmond, was grievously injured but refused aid so that others could be helped before him. Bailey would die a month later at the hospital from complications from his injuries and massive blood loss. Purdue team Captain Harry “Skeets” Leslie was found with ghastly wounds and covered up for dead. His body was transported to the morgue with the others. Leslie would later be upgraded to “alive” when, while his body lay on a cold slab at the morgue, someone noticed his right arm move slightly and he was found to have a faint pulse. Skeets was clinging to life for several weeks and needed several operations before he was out of the woods. Leslie would later go on to become the state of Indiana’s 33rd governor, the only Purdue graduate to ever hold that office. As a reminder of that Halloween train disaster, Skeets would walk with a limp for the rest of his life.

Walter Bailey, a reserve player from New Richmond, was grievously injured but refused aid so that others could be helped before him. Bailey would die a month later at the hospital from complications from his injuries and massive blood loss. Purdue team Captain Harry “Skeets” Leslie was found with ghastly wounds and covered up for dead. His body was transported to the morgue with the others. Leslie would later be upgraded to “alive” when, while his body lay on a cold slab at the morgue, someone noticed his right arm move slightly and he was found to have a faint pulse. Skeets was clinging to life for several weeks and needed several operations before he was out of the woods. Leslie would later go on to become the state of Indiana’s 33rd governor, the only Purdue graduate to ever hold that office. As a reminder of that Halloween train disaster, Skeets would walk with a limp for the rest of his life.

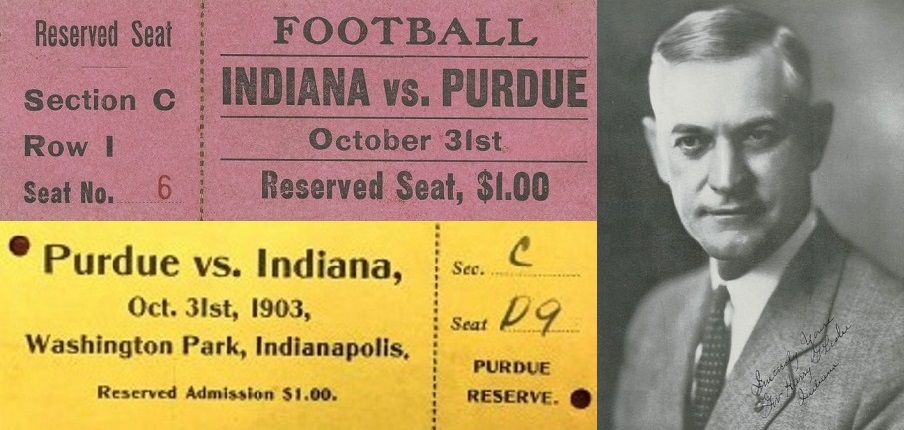

The train was traveling on what would have been the 101st birthday of school founder and namesake John Purdue (born October 31, 1802). Purdue, a wealthy landowner, politician, educator and merchant, was the primary benefactor of the University. In 1903, if you wanted to get to Indianapolis from either school, you had three choices: ride a horse and buggy, walk or take the train. Since these were the days before automobile travel was popular, train travel was the most widely accepted form of transportation.

The train was traveling on what would have been the 101st birthday of school founder and namesake John Purdue (born October 31, 1802). Purdue, a wealthy landowner, politician, educator and merchant, was the primary benefactor of the University. In 1903, if you wanted to get to Indianapolis from either school, you had three choices: ride a horse and buggy, walk or take the train. Since these were the days before automobile travel was popular, train travel was the most widely accepted form of transportation.

Unlike the raucous fans traveling in the 13 plush, modern streamliner train coaches behind them, the Boilermakers team traveled in relative silence, focusing on the task at hand, mentally preparing for their upcoming rivalry game in the cozy confines of an older wooden train car. Unfortunately, the athletes had no idea that a minor mistake would lead to a major disaster. Railroad protocol specified that “Special” trains operate independent of the regular schedule. Timing was everything in the railroad game.

Unlike the raucous fans traveling in the 13 plush, modern streamliner train coaches behind them, the Boilermakers team traveled in relative silence, focusing on the task at hand, mentally preparing for their upcoming rivalry game in the cozy confines of an older wooden train car. Unfortunately, the athletes had no idea that a minor mistake would lead to a major disaster. Railroad protocol specified that “Special” trains operate independent of the regular schedule. Timing was everything in the railroad game.

The Indianapolis star reported, “The trains came together with a great crash, which wrecked three of the passenger coaches, in addition to the engine and tender of the special train and two or three of the coal cars. The first coach on the special train was reduced to splinters. The second coach was thrown down a fifteen-foot embankment into the gravel pit and the third coach was thrown from the track to the west-side and badly wrecked. The coal cars plowed their way into the engine and demolished it completely. The coal tender was tossed to the side and turned over. A wild effort on the part of the imprisoned passengers to escape from the wrecked car followed the crash. Immediately following the wreck the students and the others turned their attention to the work of rescuing the injured, and by the time the first ambulances arrived many of the dead and suffering young men had been carried out and placed on the grass on both sides of the track.”

The Indianapolis star reported, “The trains came together with a great crash, which wrecked three of the passenger coaches, in addition to the engine and tender of the special train and two or three of the coal cars. The first coach on the special train was reduced to splinters. The second coach was thrown down a fifteen-foot embankment into the gravel pit and the third coach was thrown from the track to the west-side and badly wrecked. The coal cars plowed their way into the engine and demolished it completely. The coal tender was tossed to the side and turned over. A wild effort on the part of the imprisoned passengers to escape from the wrecked car followed the crash. Immediately following the wreck the students and the others turned their attention to the work of rescuing the injured, and by the time the first ambulances arrived many of the dead and suffering young men had been carried out and placed on the grass on both sides of the track.” The fans at the rear of the train were unaware of what happened and only felt a slight jolt as the train came to a sudden stop. These rearmost passengers wasted no time in coming to the assistance of the victims up ahead. The erstwhile revelers skidded to a stop at the scene of carnage and were horrified at the devastation before them. Acts of unselfish action made heroes out of athletes and ordinary people alike.

The fans at the rear of the train were unaware of what happened and only felt a slight jolt as the train came to a sudden stop. These rearmost passengers wasted no time in coming to the assistance of the victims up ahead. The erstwhile revelers skidded to a stop at the scene of carnage and were horrified at the devastation before them. Acts of unselfish action made heroes out of athletes and ordinary people alike. Seventeen passengers in the first coach were killed. Thirteen of the dead were members of the Purdue football team. Walter Bailey, a reserve player from New Richmond, although grievously injured, refused aid so that others could be helped. Team Captain Skeets Leslie was covered up for dead, his body transported to the morgue with the others. It was the first catastrophe to hit a major college sports team in the history of this country. The affects would be felt for decades to come and one of those players would rise from the dead, shake off accusations of association with Irvington KKK leader D.C. Stephenson, and lead his state and country through the Great Depression.

Seventeen passengers in the first coach were killed. Thirteen of the dead were members of the Purdue football team. Walter Bailey, a reserve player from New Richmond, although grievously injured, refused aid so that others could be helped. Team Captain Skeets Leslie was covered up for dead, his body transported to the morgue with the others. It was the first catastrophe to hit a major college sports team in the history of this country. The affects would be felt for decades to come and one of those players would rise from the dead, shake off accusations of association with Irvington KKK leader D.C. Stephenson, and lead his state and country through the Great Depression.

Original publish date: July 20, 2017

Original publish date: July 20, 2017 Another of the letters, dated Dec. 10, 1902, touched me personally because it was written by the sister of Louis Weichmann, the main government witness at the trial of the conspirators. Weichmann lived in Mrs. Surratt’s boarding house and many believe it was Weichmann’s testimony that got Mary Surratt hung. Weichmann moved to Anderson Indiana after the trial and founded Anderson business college. He is buried in Anderson’s St. Francis cemetery in an unmarked grave. “Dear Sir-I am sending you a copy of Sunday’s Indianapolis Journal containing a confession of one of the conspirators of President Lincoln….With best regards from our family, I remain Sincerely yours, Mrs. C.O. Crowley Sister of the late L.J. Wiechmann.” Curiously, Mrs. Crowley misspelled her own maiden name in her letter.

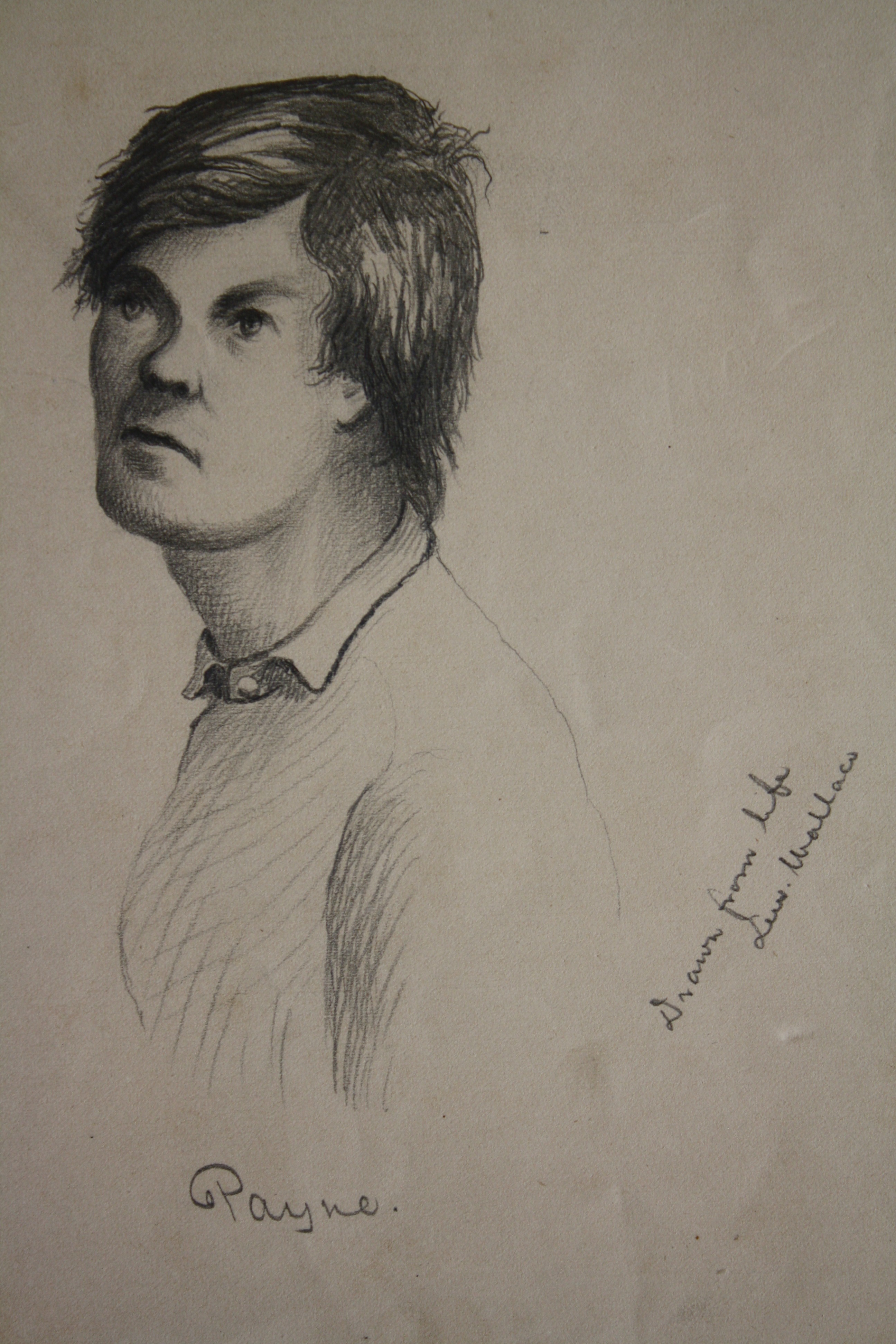

Another of the letters, dated Dec. 10, 1902, touched me personally because it was written by the sister of Louis Weichmann, the main government witness at the trial of the conspirators. Weichmann lived in Mrs. Surratt’s boarding house and many believe it was Weichmann’s testimony that got Mary Surratt hung. Weichmann moved to Anderson Indiana after the trial and founded Anderson business college. He is buried in Anderson’s St. Francis cemetery in an unmarked grave. “Dear Sir-I am sending you a copy of Sunday’s Indianapolis Journal containing a confession of one of the conspirators of President Lincoln….With best regards from our family, I remain Sincerely yours, Mrs. C.O. Crowley Sister of the late L.J. Wiechmann.” Curiously, Mrs. Crowley misspelled her own maiden name in her letter. Included within that collection was a group of several dozen items that once belonged to Osborn Oldroyd himself. This included correspondence from Anderson’s Louis Weichmann to Oldroyd about shared information for books about Abraham Lincoln both men were simultaneously working on as well as photos and several handwritten eyewitness accounts of the assassination of President Lincoln. My personal favorite was a pencil drawing of Lincoln Conspirator Lewis Thornton Powell drawn by Crawfordsville, Indiana’s General Lew Wallace.

Included within that collection was a group of several dozen items that once belonged to Osborn Oldroyd himself. This included correspondence from Anderson’s Louis Weichmann to Oldroyd about shared information for books about Abraham Lincoln both men were simultaneously working on as well as photos and several handwritten eyewitness accounts of the assassination of President Lincoln. My personal favorite was a pencil drawing of Lincoln Conspirator Lewis Thornton Powell drawn by Crawfordsville, Indiana’s General Lew Wallace.