Original publish date: October 23, 2009 Reissue date: July 9, 2020

This column was first published 11 years ago. Last weekend, I traveled to Terre Haute to check on it’s subject. Next, week, in Parts 2, 3 & 4, I will bring you up to speed on Jim Albright, the last guard to leave the notorious San Francisco Bay island prison know as “The Rock.”

Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary opened 75 years ago on August 11, 1934. I covered my visit to the “The Rock” in an earlier “Eastside Voice” article. As I stood on the same Alcatraz boat dock that received the likes of Al “Scarface” Capone, George “Machine Gun” Kelly, Alvin “Creepy” Karpis, and Robert Stroud aka “The Birdman of Alcatraz” my attention was caught by a distinguished looking gentleman with what appeared to be a uniform draped over his arm and an Alcatraz prison guard hat in his hand. I asked one of the Park Rangers standing near me what the story was and he identified the man as a former Alcatraz guard from Terre Haute, Indiana and realizing that I was on the island for a story on an Indianapolis inmate, he followed that up with, “Oh yeah, you might want to talk to him. He was the last guard off the island.” I barely heard the last line as I was race walking across the dock towards him.

As soon as I approached, the man saw my Indiana University hat and immediately extended his hand in a friendly greeting. “Indiana, huh? I’m from Terre Haute” he said, “I’m Jim Albright and I was here for 4 years until the prison closed in 1963.” He went on to tell me that he gained a unique designation as the last guard off the island when he and his family left on June 22, 1963, over 3 months AFTER the prison closed on March 21, 1963. At that moment, the V.I.P. tram arrived to escort Jim and his lovely wife Catherine up the winding 130 foot hill that covers a steep quarter mile series of roads up to the cell house where Jim was here to sign copies of his book’ “Last Guard Out“. You can imagine my distress at having just heard and comprehended this tasty nugget as the tram was pulling away. Just as I was contemplating the idea of chasing after the tram to complete the interview, I was whisked away into the bowels of building 64 under the old officer’s quarters that act as the backdrop for arrival.

Here I awaited Alcatraz park ranger John Cantwell in what once was a gun port of old “Fortress Alcatraz” with the gun ports still plainly visible in the walls. The building now acts as the Ranger’s research station and library. Cantwell graciously answered all of my questions and then led me on a tour of several areas that are strictly off limits to the general public. A dedicated public servant and a true asset to the National Park Service, Cantwell then took me up to meet up again with Jim and his wife Cathy who were busily autographing copies of the book for guests on the island in the huge new bookstore humorously referred to as the “Alcatraz Wal-Mart” by island employees. It’s interesting to note that the bookstore is located in the basement below the old kitchen, an area previously off limits to visitors probably best remembered by true Alcatraz buffs as the area where inmate / author Jim Quilllen attempted his breakout through the tunnel housing the steam pipes for the cell house. Jim greeted me wearing his original Alcatraz guard’s uniform from head to toe and looking pretty sharp I must say. I don’t know about you, but I don’t think I could fit into the same clothes I wore 20 years ago, let alone 50 years after I wore them.

Jim and Cathy had driven across country from Terre Haute to San Francisco with their nine grandchildren in tow (complete with sleeping bags & luggage) to attend the 75th anniversary celebration on “The Rock“. The grandkids got the thrill of a lifetime when the whole family spent the night in the cells on “D block” together with the other guests and families attending the official ceremonies. With a sparkle in his eye, Jim told how he made sure the family slept in the cells on the middle tier of D block because “that’s the only tier that you can see all of the San Francisco shoreline from.” He paused for a moment to make sure that I knew it was the first time he’d ever slept in a cell. Jim lamented how he sometimes runs into young people who have never heard of Alcatraz, which is hard to imagine.

In between autographs, Jim told me the story of his time on Alcatraz. He proudly pointed out that he was hired as a guard 50 years ago that very month (August 1959) as a 24 year old Iowa farm boy with no previous law enforcement experience. He was loading milk cans for Sealtest Dairy in Denver, Colorado when his corrections officer brother-in-law asked if he had ever considered a change of career. Alcatraz sounded a lot more exciting than milk cans, so in 1956 Jim, Cathy and their son Kenneth packed everything they owned into the back of a 1956 Chevy Nomad and drove out to the city by the bay. Jim took one look at the fog covered rock in the middle of San Francisco Bay and wondered what they had gotten themselves into. He was proud of the fact that both of his daughters, Vicki Lynn (Harland) and Donna Sue (Hinzman) were born on the island and their birth certificates list “Alcatraz” as their place of birth.

As Jim signed books, took pictures with guests and chatted with fans, I was able to talk to Cathy about her time on the Island. Most people unfamiliar with Alcatraz do not realize that the families of the guards lived on the island alongside the inmates; although Catherine pointed out that they rarely came into contact with each other. “There were 3 inmates that worked in the mess hall and from our windows we could see the 5 inmates that worked on the dock, but that was about it. Of course, there were no women employed on the island. The only women here were housewives and mothers.” she said. When asked what, if anything, made Alcatraz special, Catherine replied that it was the feeling of “Community” that she remembers most. Everyone knew everyone and there was always someone willing to help whenever you needed it. She remembers that she had one of the girls at 3 am and before she could pack an overnight bag for her trip to the hospital, 2 neighbors were in the apartment to help.

The Albrights remembered that the island had its own grocery store, bowling alley and movie theatre with a new movie showing every Sunday night. Jim & Cathy lived in an apartment in San Francisco for the first 6 weeks while waiting for housing to open up on the island, Cathy remembers that it was hard to find housing in the city by the bay as most apartments would allow pets, but no children. Someone had told the Albrights that the apartments on the island were furnished, so the family sold all of their furniture only to find that, when they moved in, the rooms were bare. Jim smiles broadly when he recalls that rent on the island apartment was $ 27.50 per month and included laundry, dry cleaning and utilities. Along with his uniform, Jim brought along several artifacts from his years on Alcatraz including his 1959 ID card, whistle, leather key strap, Alcatraz key “chit” tag that was exchanged for cell door keys and perhaps most interesting a couple of shiny brass Post / PX / Store tokens from the old military post years. Jim recalled how the launch boat used to dock on the west side of the island where he found the tokens shining in the moonlight in about 6 inches of water near the dock one night.

Jim then told me the story of how he gained the designation as Alcatraz Island’s “Last Guard Out“. When the prison closed on March 21, 1963, the Albright’s daughter Donna Sue was only 11 days old and suffering from a foot abnormality that required surgery. The child could not be moved in her fragile condition, so the family remained on the island for 3 more months before leaving on June 22, 1963. The Albrights were the only family left on the island aside from a night watchman and a handful of government workers left behind to remove any useful equipment that could be transferred to other prisons or facilities. In late June of 1963, Jim was one of 10 Alcatraz guards handpicked by the Warden to be transferred to the new “Supermax” prison in Marion, Illinois which was built to replace “The Rock“.

I asked Jim if being known as a former Alcatraz guard carried any weight at other facilities and he quickly replied “Oh, yes. With both guards AND Prisoners.” He remembered how he went from Alcatraz, which had 1 guard for every 3 inmates, to Marion where he worked alone from Midnight to 6 am watching 212 inmates armed only with a telephone in a prison so new that it had no doors on the cells and the containment fence that was supposed to surround the prison was incomplete. “That’s when the Alcatraz reputation made a difference. The inmates just didn’t mess with that.” He said. After Marion, Jim worked for a time at the Federal Prison in Petersburg, Virginia. Jim and Cathy Albright were transferred to the Federal Prison in Terre Haute, Indiana in 1972 and, aside from 4 years spent at a Milan, Michigan facility (1979 to 1983), they’ve been Hoosiers ever since. Jim retired as a Terre Haute Federal Prison guard in 1985.

It was on a visit to Alcatraz Island in 1998 that Jim’s identity as an Alcatraz treasure was discovered. Jim was visiting “The Rock” as a tourist with his family, having purchased a ticket just like everyone else to visit his old home and workplace. Ranger John Cantwell asked the crowd if there were anyone present with a connection to the island and Jim, humble as always, didn’t say anything. It was Jim’s brother-in-law, John Peters, who finally spoke up to reveal Jim’s past as an Island guard. For years, everyone who knew Jim’s story urged him to write a book, now Ranger Cantwell himself contributed his voice to those urgings. The end result is the 2008 book “Last Guard Out –A riveting account by the last guard to leave Alcatraz” covering Jim Albright’s years of service on “The Rock.”

In case you’re wondering, yes I bought one and gleefully asked Jim & Cathy to sign my copy and date it on that historic 75th anniversary day. Now you will have the same opportunity as I did to meet and talk with Jim and Cathy Albright right here in Irvington. The Albrights will be in Irvington for the Halloween festival, signing copies of his book “Last Guard Out” at Book Mamas book store located at 9 South Johnson Avenue in Irvington from 3 PM to 4 PM on Saturday October 31. Don’t miss this opportunity to meet a true Hoosier legend.

The book’s a great read made even better now that I know the author and his wife. Of course, I would not be true to the “spirit” of this column if I didn’t ask Jim about the ghosts of Alcatraz. Jim thought for a moment and said, “You know, I worked on this Island for 4 years at all hours of the night and day. Midnight, 3 am, 4 am, every possible time slot and I never heard anything that I could call a ghost.” It does make me wonder though, what do you think those 9 grandkids who spent the night in Alcatraz’s legendary spooky cells of D block would say if I asked them the same thing?

After the minister’s arrived, Lincoln rang a bell and then led the wedding party into a big room, Elizabeth recalled. The president stood alongside the minister and not only did he give the bride away but also acted as the groom’s best man. Elizabeth recalled how he smiled throughout the ceremony. She stated that a Cabinet member stood up with them, but couldn’t recall his name or that of the minister. Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln were the first to shake the newlyweds’ hands. Elizabeth’s most vivid recollection of the nuptials was how scared she was. The president chatted with them awhile and then returned to his office with the unnamed Cabinet member. Elizabeth had worn a plain white cashmere dress for the ceremony. Afterwards, the couple was taken to separate rooms in the White House to change clothes, where Elizabeth changed into a navy blue cashmere dress.

After the minister’s arrived, Lincoln rang a bell and then led the wedding party into a big room, Elizabeth recalled. The president stood alongside the minister and not only did he give the bride away but also acted as the groom’s best man. Elizabeth recalled how he smiled throughout the ceremony. She stated that a Cabinet member stood up with them, but couldn’t recall his name or that of the minister. Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln were the first to shake the newlyweds’ hands. Elizabeth’s most vivid recollection of the nuptials was how scared she was. The president chatted with them awhile and then returned to his office with the unnamed Cabinet member. Elizabeth had worn a plain white cashmere dress for the ceremony. Afterwards, the couple was taken to separate rooms in the White House to change clothes, where Elizabeth changed into a navy blue cashmere dress.

These unique roadside attractions began popping up along our highways in the 1930s and flourished into the 1960s. But the 1950s were their heyday. The Ike Era fifties was the decade of car culture; gas was cheap and families took to the open road, many for the very first time. The US interstate highway system was authorized in 1956 and construction began almost immediately in many states. Until then, families relied on connecting state road systems that took them on meandering journeys through big cities and small towns alike.

These unique roadside attractions began popping up along our highways in the 1930s and flourished into the 1960s. But the 1950s were their heyday. The Ike Era fifties was the decade of car culture; gas was cheap and families took to the open road, many for the very first time. The US interstate highway system was authorized in 1956 and construction began almost immediately in many states. Until then, families relied on connecting state road systems that took them on meandering journeys through big cities and small towns alike. Although modern construction has ensured that you are never far from fast food and gas, if you drive highway 40 today, it is easy to imagine how that drive must have felt back in the day. Today, driving along many of Indiana’s classic highways (Michigan Road, Brookville Road, Washington Street, Lincoln Highway) traces of old gift shops, restaurants, amusement parks and motels dot the landscape. Many of you can easily recall the giant TeePees that crowned the roof of the aptly named “TeePee” restaurants on the grounds of the state fairgrounds and on the cities southside. For me, I’ll always remember the giant coffee pot that formed the roof of the “Coffee Pot” restaurant in Pennville near Richmond on the National Road.

Although modern construction has ensured that you are never far from fast food and gas, if you drive highway 40 today, it is easy to imagine how that drive must have felt back in the day. Today, driving along many of Indiana’s classic highways (Michigan Road, Brookville Road, Washington Street, Lincoln Highway) traces of old gift shops, restaurants, amusement parks and motels dot the landscape. Many of you can easily recall the giant TeePees that crowned the roof of the aptly named “TeePee” restaurants on the grounds of the state fairgrounds and on the cities southside. For me, I’ll always remember the giant coffee pot that formed the roof of the “Coffee Pot” restaurant in Pennville near Richmond on the National Road. But, who remembers the “Mr. Bendo”, the muffler man? These giant statues routinely stood outside auto shops, usually with one arm outstretched while towering over the road with a muffler resting in his curved hand. Spotted in various incarnations all over the United States, these advertising icons were extraordinarily popular throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Legend claims that all of the original Muffler Men came from a single mold owned by Prewitt Fiberglass (later International Fiberglass). The first Muffler Man was allegedly a giant Paul Bunyan developed for a café on Route 66 in Arizona. Later incarnations were Native Americans, cowboys, spacemen and even the Uniroyal girl, who appeared in both a dress and a bikini. These behemoths either elicited fear or joy, but never failed to spur the imagination. Locally, you can find one of these “Mr. Bendo” statues at 1250 W. 16th St.

But, who remembers the “Mr. Bendo”, the muffler man? These giant statues routinely stood outside auto shops, usually with one arm outstretched while towering over the road with a muffler resting in his curved hand. Spotted in various incarnations all over the United States, these advertising icons were extraordinarily popular throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Legend claims that all of the original Muffler Men came from a single mold owned by Prewitt Fiberglass (later International Fiberglass). The first Muffler Man was allegedly a giant Paul Bunyan developed for a café on Route 66 in Arizona. Later incarnations were Native Americans, cowboys, spacemen and even the Uniroyal girl, who appeared in both a dress and a bikini. These behemoths either elicited fear or joy, but never failed to spur the imagination. Locally, you can find one of these “Mr. Bendo” statues at 1250 W. 16th St. Closeby, there is a giant Uncle Sam and his two smaller nephews on Shadeland Ave (between Washington St and 10th). There are two giant globes, one on Michigan Road on the way to Zionsville and the other near the pyramids visible from the interstate. There is a large dairy cow on South Shortridge Rd (between Washington St and Brookville Rd) sitting behind a 10-foot chain link fence topped with barbed wire and guard at the gate. There are two large swans in the middle of ponds, one on Mitthoffer (Between 21st St and 30th St) and the other on Pendleton Pike. Incidently there is a big fiberglass cow at 9623 Pendleton Pike near the afore mentioned swan.

Closeby, there is a giant Uncle Sam and his two smaller nephews on Shadeland Ave (between Washington St and 10th). There are two giant globes, one on Michigan Road on the way to Zionsville and the other near the pyramids visible from the interstate. There is a large dairy cow on South Shortridge Rd (between Washington St and Brookville Rd) sitting behind a 10-foot chain link fence topped with barbed wire and guard at the gate. There are two large swans in the middle of ponds, one on Mitthoffer (Between 21st St and 30th St) and the other on Pendleton Pike. Incidently there is a big fiberglass cow at 9623 Pendleton Pike near the afore mentioned swan. The old Galyan’s bear statue sits on the edge of the Eagle Creek Reservoir. When Dick’s Sporting Goods purchased Galyan’s, the company donated the statue to the City of Indianapolis. There are two huge bowling pins, one at Woodland bowl on the northside and the other at Expo bowl on the southside (visible from I-465). Don’t forget about the giant dinosaurs hatching from eggs at the Children’s Museum on the corner of 30th and N. Meridian Streets near downtown.

The old Galyan’s bear statue sits on the edge of the Eagle Creek Reservoir. When Dick’s Sporting Goods purchased Galyan’s, the company donated the statue to the City of Indianapolis. There are two huge bowling pins, one at Woodland bowl on the northside and the other at Expo bowl on the southside (visible from I-465). Don’t forget about the giant dinosaurs hatching from eggs at the Children’s Museum on the corner of 30th and N. Meridian Streets near downtown. If you’re traveling to Logansport, you can visit three giant statues in the same town; Mr. Happy Burger on the corner of US Hwy 24/W. Market St. and W. Broadway St. features a fiberglass black bull wearing a chef’s hat and a bib as does the Mr. Happy Burger located at 3131 E. Market St. along with a giant chicken statue at 7118 W. US Hwy 24 (on the north side) that you can see from the road. Muncie has two giants; A big fiberglass muffler man stands alongside the scissor-lifts & heavy equipment in the Mac Allister rental lot at 3500 N. Lee Pit Rd. and a Paul Bunyan statue is the mascot of a bar named Timbers at 2770 W. Kilgore Ave.

If you’re traveling to Logansport, you can visit three giant statues in the same town; Mr. Happy Burger on the corner of US Hwy 24/W. Market St. and W. Broadway St. features a fiberglass black bull wearing a chef’s hat and a bib as does the Mr. Happy Burger located at 3131 E. Market St. along with a giant chicken statue at 7118 W. US Hwy 24 (on the north side) that you can see from the road. Muncie has two giants; A big fiberglass muffler man stands alongside the scissor-lifts & heavy equipment in the Mac Allister rental lot at 3500 N. Lee Pit Rd. and a Paul Bunyan statue is the mascot of a bar named Timbers at 2770 W. Kilgore Ave. There is a car-sized basketball shoe at the Steve Alford All-American Inn on State Road 3 in New Castle and you can visit the towering, thickly-clothed “Icehouse man” painted in cool blue colors, the mascot of a bar named Icehouse at 1550 Walnut St. in New Castle. A balloon-shaped man with a chef’s hat, known by locals as “The Baker Man” is perched atop a pole with his arm raised in a friendly wave at 315 S. Railroad St. in Shirley, Indiana. And of course, who can forget the giant Santa Claus that greets visitors to Santa Claus, Indiana.

There is a car-sized basketball shoe at the Steve Alford All-American Inn on State Road 3 in New Castle and you can visit the towering, thickly-clothed “Icehouse man” painted in cool blue colors, the mascot of a bar named Icehouse at 1550 Walnut St. in New Castle. A balloon-shaped man with a chef’s hat, known by locals as “The Baker Man” is perched atop a pole with his arm raised in a friendly wave at 315 S. Railroad St. in Shirley, Indiana. And of course, who can forget the giant Santa Claus that greets visitors to Santa Claus, Indiana. I’m sure I’m forgetting a few, perhaps many, but if this list helps stir up some old roadside memories among you, or better yet, gets you charged up to take an inexpensive holiday in search of roadside oddities, well, then it was a worthwhile read.

I’m sure I’m forgetting a few, perhaps many, but if this list helps stir up some old roadside memories among you, or better yet, gets you charged up to take an inexpensive holiday in search of roadside oddities, well, then it was a worthwhile read.

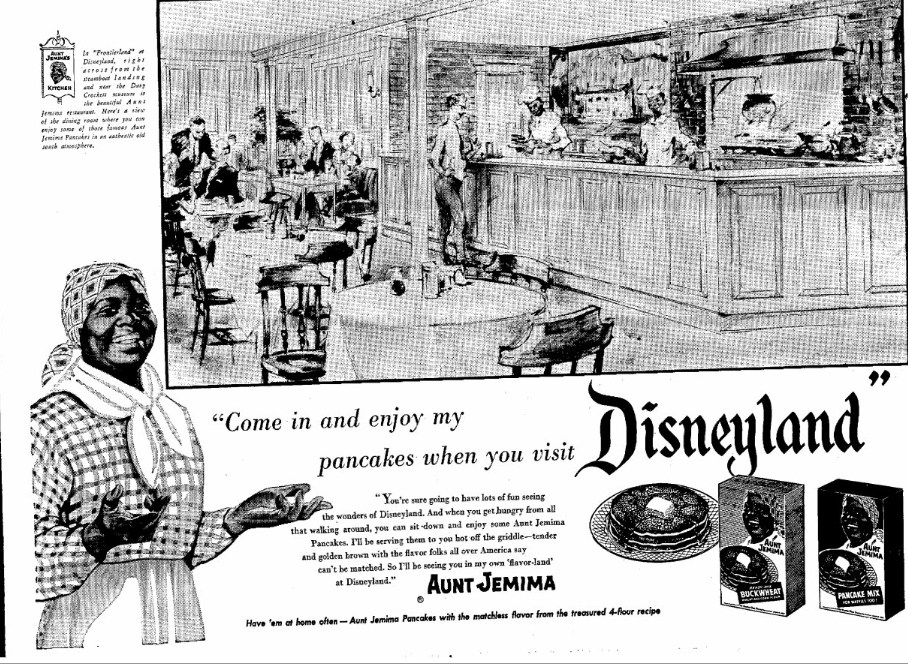

From there, well, nobody knows. For the answer, you need look no further than the fact that there are no McDonald’s at Disney. It should be noted that there were SOME franchise restaurants in Disneyland during those first first years. They included the Aunt Jemima pancake and waffle house in Frontierland and the Chicken of the Sea Pirate Ship in Fantasyland.

From there, well, nobody knows. For the answer, you need look no further than the fact that there are no McDonald’s at Disney. It should be noted that there were SOME franchise restaurants in Disneyland during those first first years. They included the Aunt Jemima pancake and waffle house in Frontierland and the Chicken of the Sea Pirate Ship in Fantasyland. To his dying day, Ray Kroc insisted that the reason the “world’s first McDonald’s” was not featured inside Disneyland at the park’s July 17, 1955 grand opening was because the head of concessions had tried to force Ray to raise the price of his french fries by a nickle (from 10 cents to 15 cents) for the Disneyland crowd. Kroc, the man in charge of McDonald’s franchising, believed that he was being charged a franchise fee by virtue of Walt Disney Productions tacking on a concessionaire’s fee. Kroc, the consummate businessman, said he wasn’t about to give away 1/3 of his profits while gouging his customers. Great story, but by the time Disneyland debuted, Kroc had only opened one McDonald’s franchise (in Des Plaines, Illinois on April 15, 1955). So he had no loyal customers to offend…yet. Well, no customers within 2,000 miles anyway.

To his dying day, Ray Kroc insisted that the reason the “world’s first McDonald’s” was not featured inside Disneyland at the park’s July 17, 1955 grand opening was because the head of concessions had tried to force Ray to raise the price of his french fries by a nickle (from 10 cents to 15 cents) for the Disneyland crowd. Kroc, the man in charge of McDonald’s franchising, believed that he was being charged a franchise fee by virtue of Walt Disney Productions tacking on a concessionaire’s fee. Kroc, the consummate businessman, said he wasn’t about to give away 1/3 of his profits while gouging his customers. Great story, but by the time Disneyland debuted, Kroc had only opened one McDonald’s franchise (in Des Plaines, Illinois on April 15, 1955). So he had no loyal customers to offend…yet. Well, no customers within 2,000 miles anyway. It is more likely to say that while the executives in charge of Disneyland’s concessions were undoubtedly intrigued by Ray’s “fast food” proposal, “war buddy” or not, Kroc just didn’t have enough experience in the restaurant business to take that gamble. So, despite how Kroc spun the tale to reporters from the 1950s forward, while there was some discussion of putting a McDonald’s inside the theme park, the project never really made it past the talking stage. But Ray Kroc would never let the truth stand in the way of a good story.

It is more likely to say that while the executives in charge of Disneyland’s concessions were undoubtedly intrigued by Ray’s “fast food” proposal, “war buddy” or not, Kroc just didn’t have enough experience in the restaurant business to take that gamble. So, despite how Kroc spun the tale to reporters from the 1950s forward, while there was some discussion of putting a McDonald’s inside the theme park, the project never really made it past the talking stage. But Ray Kroc would never let the truth stand in the way of a good story.

One of those “must see” old timey casinos is located about 30 miles southwest of the Vegas strip in a desert town called Primm, Nevada not far from the California border. Known as “Whiskey Pete’s”, the casino covers 35,000 square feet, has 777 rooms, a large swimming pool, gift shop and four restaurants. The casino is named after gas station owner Pete MacIntyre. “Whiskey Pete” had a difficult time making ends meet selling gas, so he resorted to bootlegging and an idea was born. When Whiskey Pete died in 1933, he was secretly buried standing up with a bottle of whiskey in his hands so he could watch over the area. Decades later, his unmarked grave was accidentally exhumed by workers building a connecting bridge from Whiskey Pete’s to Buffalo Bill’s (on the other side of I-15). According to legend, the body was reburied in one of the caves where Pete once cooked up his moonshine.

One of those “must see” old timey casinos is located about 30 miles southwest of the Vegas strip in a desert town called Primm, Nevada not far from the California border. Known as “Whiskey Pete’s”, the casino covers 35,000 square feet, has 777 rooms, a large swimming pool, gift shop and four restaurants. The casino is named after gas station owner Pete MacIntyre. “Whiskey Pete” had a difficult time making ends meet selling gas, so he resorted to bootlegging and an idea was born. When Whiskey Pete died in 1933, he was secretly buried standing up with a bottle of whiskey in his hands so he could watch over the area. Decades later, his unmarked grave was accidentally exhumed by workers building a connecting bridge from Whiskey Pete’s to Buffalo Bill’s (on the other side of I-15). According to legend, the body was reburied in one of the caves where Pete once cooked up his moonshine. Oh, I forgot to mention that Whiskey Pete’s is also home to the Bonnie and Clyde death car. As detailed in part III of this series, the car has had a long strange trip to Primm. The bullet-ridden car toured carnivals, amusement parks, flea markets, and state fairs for decades before being permanently parked on the plush carpet between the main cashier cage and a lifesize caged effigy of Whiskey Pete himself. According to the “Roadside America” website, “For a time it was in the Museum of Antique Autos in Princeton, Massachusetts, then in the 1970s it was at a Nevada race track where people could sit in it for a dollar. A decade later it was in a Las Vegas car museum; a decade after that it was in a casino near the California / Nevada state line. It was then moved to a different casino on the other side of the freeway, then it went on tour to other casinos in Iowa, Missouri, and northern Nevada.

Oh, I forgot to mention that Whiskey Pete’s is also home to the Bonnie and Clyde death car. As detailed in part III of this series, the car has had a long strange trip to Primm. The bullet-ridden car toured carnivals, amusement parks, flea markets, and state fairs for decades before being permanently parked on the plush carpet between the main cashier cage and a lifesize caged effigy of Whiskey Pete himself. According to the “Roadside America” website, “For a time it was in the Museum of Antique Autos in Princeton, Massachusetts, then in the 1970s it was at a Nevada race track where people could sit in it for a dollar. A decade later it was in a Las Vegas car museum; a decade after that it was in a casino near the California / Nevada state line. It was then moved to a different casino on the other side of the freeway, then it went on tour to other casinos in Iowa, Missouri, and northern Nevada.  Complicating matters was the existence of at least a half-dozen fake Death Cars and the Death Car from the 1967 Bonnie and Clyde movie (which was in Louisiana and then Washington, DC, but now is in Tennessee).” Just in case of any remaining confusion, the Primm car is accompanied by a bullet riddled sign reading: “Yes, this is the original, authentic Bonnie and Clyde death car” (in all caps for emphasis).

Complicating matters was the existence of at least a half-dozen fake Death Cars and the Death Car from the 1967 Bonnie and Clyde movie (which was in Louisiana and then Washington, DC, but now is in Tennessee).” Just in case of any remaining confusion, the Primm car is accompanied by a bullet riddled sign reading: “Yes, this is the original, authentic Bonnie and Clyde death car” (in all caps for emphasis).

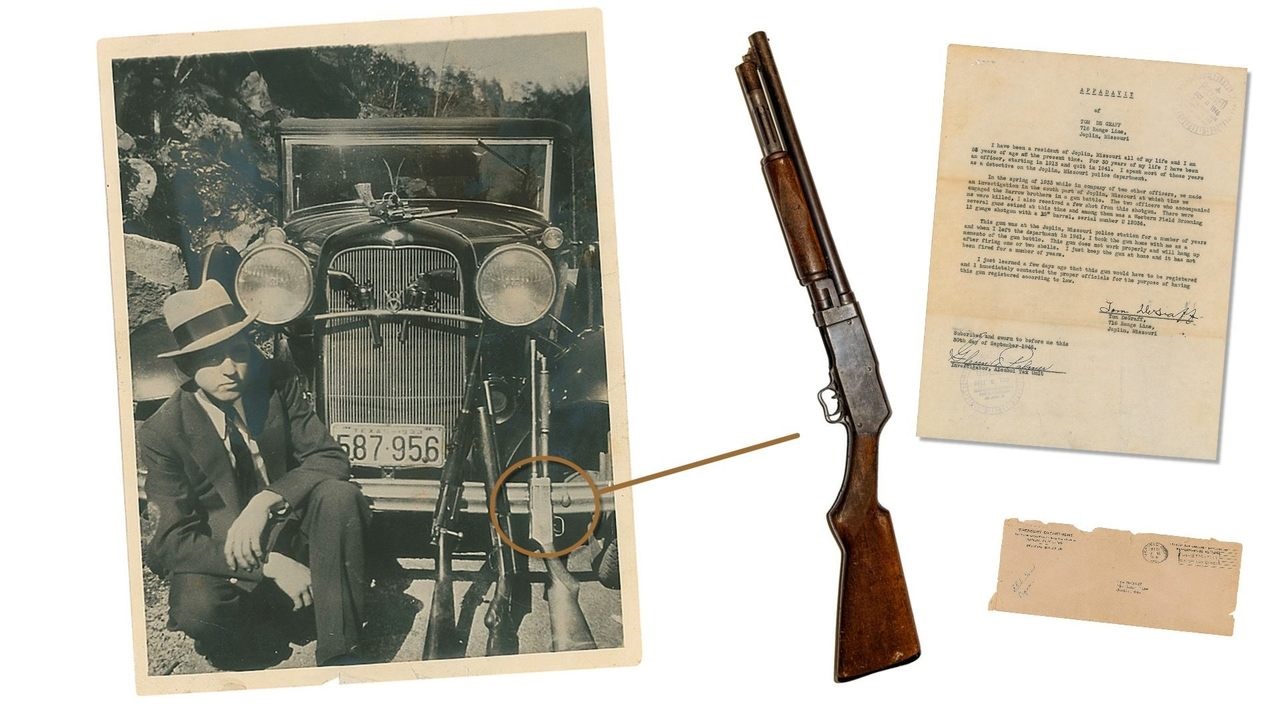

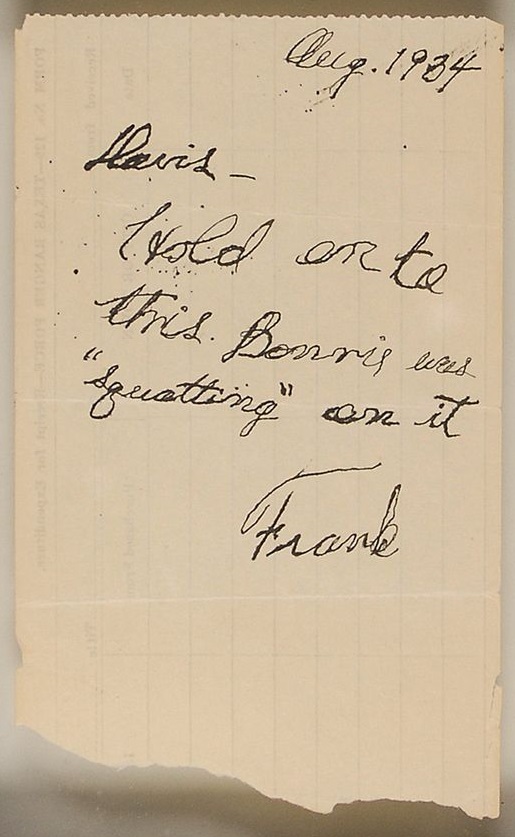

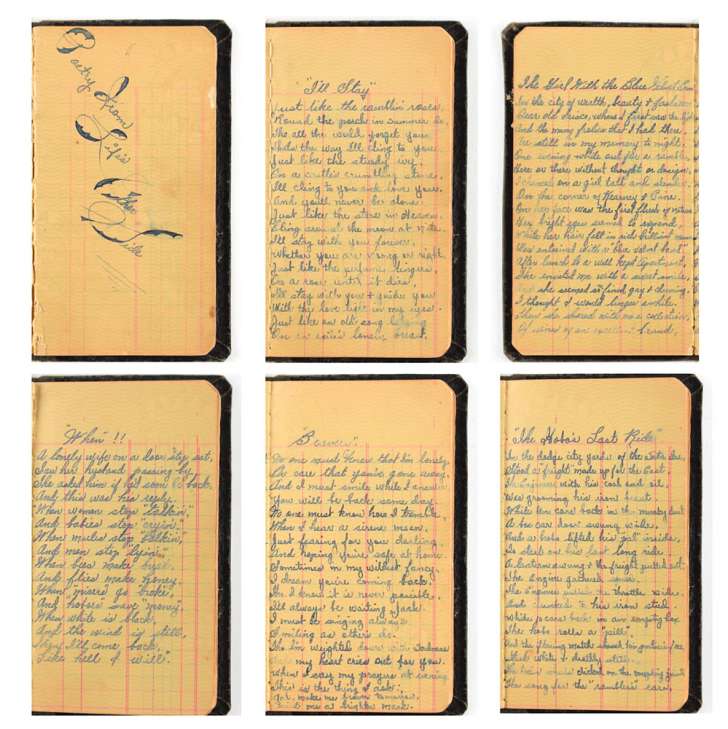

The walls surrounding the death car are festooned with authentic newspapers detailing the outlaw lover’s demise and letters vouching to the vehicle’s authenticity. Cases contain other Bonnie and Clyde relics like a belt given by Clyde to his sister and classic candid photos of the star-crossed lovers and their families.

The walls surrounding the death car are festooned with authentic newspapers detailing the outlaw lover’s demise and letters vouching to the vehicle’s authenticity. Cases contain other Bonnie and Clyde relics like a belt given by Clyde to his sister and classic candid photos of the star-crossed lovers and their families. A movie, obviously created many years ago, recreates the event using newsreel footage, landscape photography and contemporary interviews with family members and eyewitnesses. Here, it is revealed that the shirt was found, decades after the outlaw’s death, secreted away in a sealed metal box along with Clyde’s hat. The film itself has become a piece of Americana and the images of Bonnie’s torn and tattered body left twitching in the car, resting silently mere yards away, are equally breathtaking. Nearby, although not nearly as shocking as the Bonnie and Clyde death car, another bullet-scarred automobile is on display. This one first belonged to gangster Dutch Schultz and later, Al Capone. Signs around the car proclaim that the doors are filled with lead and, judging by the pockmarks of the bullets denting the exterior, it is true. Although, like every casino, Whiskey Pete’s job remains separating gamblers from their money, both cars are on display 24 hours a day for free.

A movie, obviously created many years ago, recreates the event using newsreel footage, landscape photography and contemporary interviews with family members and eyewitnesses. Here, it is revealed that the shirt was found, decades after the outlaw’s death, secreted away in a sealed metal box along with Clyde’s hat. The film itself has become a piece of Americana and the images of Bonnie’s torn and tattered body left twitching in the car, resting silently mere yards away, are equally breathtaking. Nearby, although not nearly as shocking as the Bonnie and Clyde death car, another bullet-scarred automobile is on display. This one first belonged to gangster Dutch Schultz and later, Al Capone. Signs around the car proclaim that the doors are filled with lead and, judging by the pockmarks of the bullets denting the exterior, it is true. Although, like every casino, Whiskey Pete’s job remains separating gamblers from their money, both cars are on display 24 hours a day for free. The interior of the Pioneer Saloon remains unchanged. It is easy to imagine Gone with the Wind star Gable drowning his sorrows at a rickety table or bracing himself against the cowboy bar and it’s brass boot rail. Ask and the bartender will point out the cigarette burn holes in the bar caused by Gable when he passed out from a mixture of grief and alcohol during his somber vigil. The tin ceiling remains as do the ancient celing fans (it gets HOT in the desert) and the walls are peppered with bullet holes left by cowboys who rode off into the sunset generations ago. The bar’s backroom is a shrine to the Lombard / Gable tragedy but sadly most of the relics on display there are modern photocopies and recreations. Locals claim that Carole Lombard’s ghost haunts the saloon in a desperate attempt to contact her grieving husband. The saloon is also reportedly haunted by the ghost of an old “Miner 49er” who appears drinking alone at the far end of the bar before vanishing into thin air. Millennials flock to the bar as the birthplace of the game “Fallout: New Vegas” which also has a small shrine located there.

The interior of the Pioneer Saloon remains unchanged. It is easy to imagine Gone with the Wind star Gable drowning his sorrows at a rickety table or bracing himself against the cowboy bar and it’s brass boot rail. Ask and the bartender will point out the cigarette burn holes in the bar caused by Gable when he passed out from a mixture of grief and alcohol during his somber vigil. The tin ceiling remains as do the ancient celing fans (it gets HOT in the desert) and the walls are peppered with bullet holes left by cowboys who rode off into the sunset generations ago. The bar’s backroom is a shrine to the Lombard / Gable tragedy but sadly most of the relics on display there are modern photocopies and recreations. Locals claim that Carole Lombard’s ghost haunts the saloon in a desperate attempt to contact her grieving husband. The saloon is also reportedly haunted by the ghost of an old “Miner 49er” who appears drinking alone at the far end of the bar before vanishing into thin air. Millennials flock to the bar as the birthplace of the game “Fallout: New Vegas” which also has a small shrine located there.

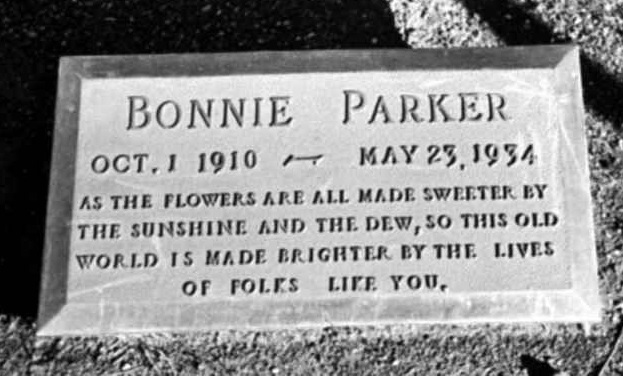

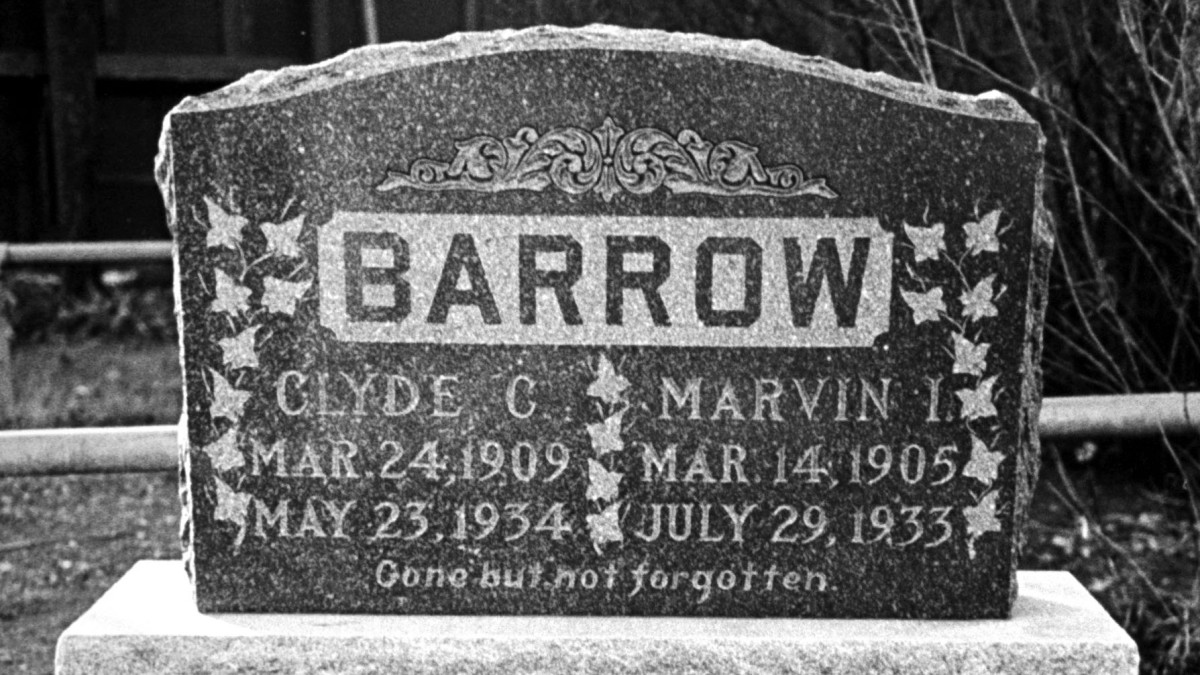

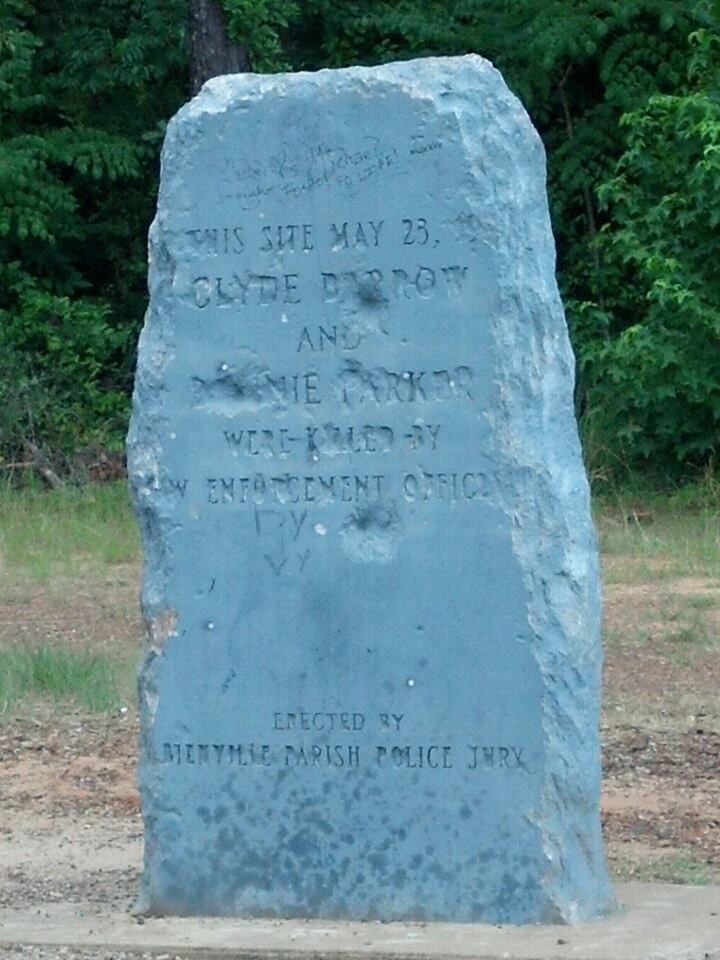

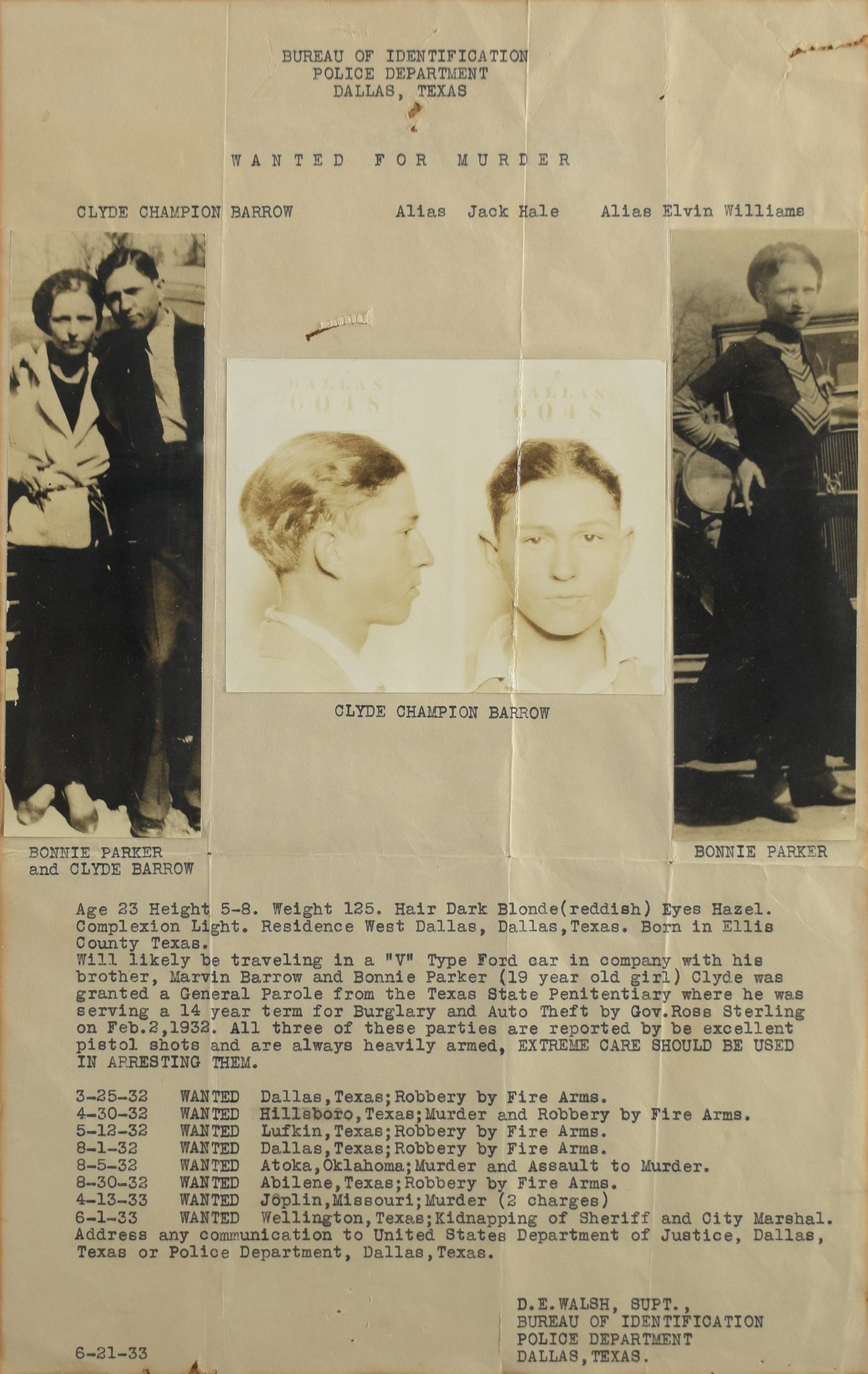

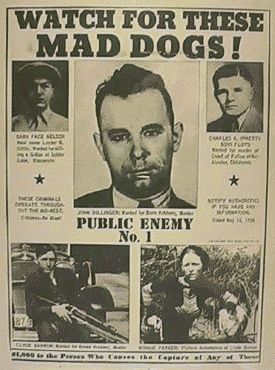

During the Great Depression, some viewed the duo as near folk heroes, like Robin Hood and Maid Marian. And, although Hoosier outlaw John Dillinger reportedly once told a reporter that Bonnie and Clyde were “a couple of punks”, he and his fellow gang member Pretty Boy Floyd reportedly sent flowers to their funeral homes. The Barrow gang killed a total of 13 people, including nine police officers. They finally met their match on May 23, 1934, when six police officers ambushed them and shot some 130 rounds into the car. Dillinger outlasted Bonnie and Clyde by about two months – he met his maker on July 22, 1934. Truth is, proceeds from auctions of items associated with these outlaws over the past two decades (which number in the millions of dollars) far outdistance the proceeds of all of their robberies combined.

During the Great Depression, some viewed the duo as near folk heroes, like Robin Hood and Maid Marian. And, although Hoosier outlaw John Dillinger reportedly once told a reporter that Bonnie and Clyde were “a couple of punks”, he and his fellow gang member Pretty Boy Floyd reportedly sent flowers to their funeral homes. The Barrow gang killed a total of 13 people, including nine police officers. They finally met their match on May 23, 1934, when six police officers ambushed them and shot some 130 rounds into the car. Dillinger outlasted Bonnie and Clyde by about two months – he met his maker on July 22, 1934. Truth is, proceeds from auctions of items associated with these outlaws over the past two decades (which number in the millions of dollars) far outdistance the proceeds of all of their robberies combined. For my part, when we told our 25-year-old son about our anniversary trip to Las Vegas, he remained nonplussed by saying, “I would only want to go out there to see a town called Primm.” To which we said “been there, done that.” His reply, “I’d also like to go to a little town called Good Springs.” We answered, “Been there too.” He concluded by saying he’d like to see an old dive bar named the “Pioneer Saloon.” He was shocked when we said we went there too. Of course, the reason he wants to venture out there is video game related, not history related. Nonetheless, he was chagrined by our answers. I guess we old folks aren’t so square after all.

For my part, when we told our 25-year-old son about our anniversary trip to Las Vegas, he remained nonplussed by saying, “I would only want to go out there to see a town called Primm.” To which we said “been there, done that.” His reply, “I’d also like to go to a little town called Good Springs.” We answered, “Been there too.” He concluded by saying he’d like to see an old dive bar named the “Pioneer Saloon.” He was shocked when we said we went there too. Of course, the reason he wants to venture out there is video game related, not history related. Nonetheless, he was chagrined by our answers. I guess we old folks aren’t so square after all.