Original publish date: July 18, 2019

The Hoosier Lincoln community is losing a shining light in Fort Wayne next week. Jane E. Gastineau, Lincoln Librarian of the Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection (LFFC) housed at the Allen County Public Library is retiring on July 31st. Jane closes her twelve year stint of meticulously cataloging, documenting and digitizing Abraham Lincoln and all Hoosiers owe her a heartfelt thank you.

Jane steered the Fort Wayne Lincoln ship through perhaps its most turbulent time; the acquisition of the Collection by the State of Indiana. The assemblage represents a world-class research collection of documents, artifacts, books, prints, photographs, manuscripts, and 19th-century art related to Lincoln. Like many involved in the Hoosier Lincoln community, I recall the announcement (in March 2008) that the Fort Wayne Lincoln museum would close and watched with acute interest for word of its final disposition. Would it be sold at auction? Would it be acquired by a wealthy collector? Or would it remain in Indiana?

The Lincoln Financial Foundation, owner of the collection, was adamant on two points. First, the organization wanted the collection to be donated to an institution capable of providing permanent care and broad public access. Second, the collection would not be broken up among multiple owners. In other words, this collection which had been built over so many decades was not for sale and would remain intact. This came as a relief to Lincoln fans all over the country. However, the question of where it would land remained indeterminate for some time and not without controversy.

I recall visiting with James Cornelius, former curator of Lincoln artifacts at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield Illinois, back in early 2009. Although my research visit was in no way connected to the Lincoln Financial collection disposition question, since I was a Hoosier, Dr. Cornelius, whom I admire, could not resist asking me how it happened. I had to inform him that I really had no idea and could not even begin to offer an explanation. Jane Gastineau cleared that question up for me.

“The advantage of our facility, aside from it being in Indiana, was our technical ability. We could have any object or artifact digitized, on the web and available to researchers in no more than three days.” That may seem like a given to researchers nowadays, but a decade ago, most research facilities were still working with copy and fax machines; not exactly on the cutting edge of the digital universe.

“The advantage of our facility, aside from it being in Indiana, was our technical ability. We could have any object or artifact digitized, on the web and available to researchers in no more than three days.” That may seem like a given to researchers nowadays, but a decade ago, most research facilities were still working with copy and fax machines; not exactly on the cutting edge of the digital universe.

In December of 2008 those conditions were met when one of the largest private collections of Abraham Lincoln-related material in existence was donated to the people of Indiana. Today the Collection is housed in two institutions, the Indiana State Museum in Indianapolis and the Allen County Public Library in Fort Wayne. This allows the Collection to live on in its entirety, available to the public in various exhibits at all times. And, especially in my case, the digitized LFFC is available on-line to researchers 24-7.

To date the LFFC has 15,219 items available in full text through Internet Archive and have had 5,373,223 views of that material since late 2009. The library collection has 4,907 photographs and 3,021 documents/manuscripts online. Most importantly, additional manuscripts and transcriptions are being added weekly as they are processed. Lincoln programming at the library is also taped, and there are 51 programs viewable online at https://archive.org/details/allencountylincolnprograms.

I recently spent a couple days in Fort Wayne researching Lincoln. I found Jane Gastineau hard at work deciphering, transcribing and cataloging the Lincoln collection. Depending on the day (or the hour) Jane may be working on Abraham Lincoln, his wife Mary, their son Robert or, just as often, any number of the researchers and volunteer catalogers from generations prior. Seems that 210 years after the Great Emancipator’s birth, there is still plenty of work to be done within the Lincoln genre.

“Standards of best practice re: collection building, collection record keeping, and professional conflict of interest have changed over the decades. That means that some of the practices (of early Lincoln collector/curators) may look sketchy to us, but they were acceptable at the time. Some of the older practices also make tracking provenance a bit tricky and occasionally impossible, which is frustrating for us. Hopefully we’re doing better so that those who come after us won’t find us sketchy.”

According to Gastineau, “I work entirely with the part of the collection housed at the Allen County Public Library. The LFFC is supported by an endowment under the Friends of the Lincoln Collection of Indiana. The Allen County Public Library provides our space and supports programming at the library, but all other financial support (salaries, travel for conferences, supplies, digitizing expenses, acquisitions, etc.) are paid through the Friends endowment.”

According to Gastineau, “I work entirely with the part of the collection housed at the Allen County Public Library. The LFFC is supported by an endowment under the Friends of the Lincoln Collection of Indiana. The Allen County Public Library provides our space and supports programming at the library, but all other financial support (salaries, travel for conferences, supplies, digitizing expenses, acquisitions, etc.) are paid through the Friends endowment.”

She continues, “There are two of us that work fulltime with the collection. I moved with the collection from The Lincoln Museum (where I had been collections manager) to the library on July 1, 2009. I know the collection pretty well—though we’re still finding things we didn’t know we had—and I’ve learned a great deal about Lincoln and those surrounding him and “collecting him.” But I don’t consider myself a Lincoln expert and certainly not a Lincoln scholar. I just know a lot about him—and I admire him.” Jane is quick to point out that, “I’m not a solo act.” She’s had three coworkers over the years—Cindy VanHorn (who came with Jane from the Fort Wayne Lincoln Museum) and is currently working part time with the portion of the LFFC housed at the Indiana State Museum; Adriana Maynard Harmeyer who left to join the Archives/Special Collections at Purdue University and Jane’s associate Lincoln-librarian (and editor of the LFFC’s Lincoln Lore publication) Emily Rapoza.

Although Jane truly loves her job, she is looking forward to retirement. For now, the librarian has no plans to return to her old post, even as a volunteer, simply because, “I don’t want my successor to feel like I’m looking over his/her shoulder and judging whether things are being done right. I had my time here, and I think my coworkers and I accomplished a great deal with organizing and documenting the collection and making it widely accessible. But now I need to stay out of my successor’s way. I work with an amazing collection, and there’s always something new to discover or a new problem to solve. This job has let me work as a librarian, an archivist, a program planner, a program presenter, a creator of exhibits on site and online, a researcher, a reference for researchers, a tour guide, an instructor for interns. It’s been a great twelve years.”

When asked what she will miss the most, Jane states that she will miss the “everyday discoveries”. Whether she is learning something new from a tour guest, researcher or from the collection itself, Jane smiles widest when she makes a new discovery. While escorting me on a special tour of the LFFC holdings on display in the climate controlled, secure vault hidden deep within the library, Jane relayed the story of one such discovery made some time ago, quite by accident.

“For whatever reason, it was a slow day and I was poking through some uncatalogued material from the James Hickey collection. I ran across this scrap of paper.” At this point Jane removes the protective jet black cover from a locked case at one side of the room to reveal several documents written and signed by Abraham Lincoln himself. She directs my attention to a small note in the familiar handwriting of our sixteenth President. “Read it,” Jane states, “See if you notice the one word that makes people chuckle when they see it.”

“For whatever reason, it was a slow day and I was poking through some uncatalogued material from the James Hickey collection. I ran across this scrap of paper.” At this point Jane removes the protective jet black cover from a locked case at one side of the room to reveal several documents written and signed by Abraham Lincoln himself. She directs my attention to a small note in the familiar handwriting of our sixteenth President. “Read it,” Jane states, “See if you notice the one word that makes people chuckle when they see it.”

“There is reason to believe this Corneilus Garvin is an idiot, and that he is kept in the 52nd N.Y. concealed + denied to avoid an exposure of guilty parties. Will Sec. of War please have the thing probed? A. Lincoln May 21, 1864” Jane reveals that the word “idiot” in Lincoln’s note never fails to elicit a giggle, “But that word doesn’t mean what they think it means. Idiot was the way they described intellectual disabilities back then.”

Jane explains that she googled the soldier’s name and learned that this note, along with 60 other supporting documents found with it, were the key to a mystery that ultimately led to a book by an Irish historian named Damian Shiels who also authors a blog called “Irish in the American Civil War”. Jane states that Shiels “had pieced the Garvin story together from newspaper accounts and pension records in the US National Archives. His post included the information that Garvin’s documents had been offered for sale in the 1940s and requested that, if anyone knew where the documents were, he be informed. So I emailed him that we had the docs and digitized them and put them online in our collection so he could use them. In 2016 he published a book titled “The Forgotten Irish: Irish Emigrant Experiences in America,” and the story of Catharine and Cornelius Garvin is the first story—about 12 pages.”

Shiels reveals, “During the Civil War, many freed slaves and young men were abducted from their families, and purchased by the Union in order to replace men who sought to avoid warfare for various reasons. In 1863, a widow by the name of Mrs. Catherine Garvin of Troy, New York, was informed that her son, Cornelius, was missing. In efforts to connect with her lost son, Mrs. Garvin not only searched the camps and hospitals where her son was believed to be, she brought her story to local politicians, newspapers, and suddenly the story of the missing boy “Con” began to receive attention. Mrs. Garvin’s story became such a sensation that it received attention from President Abraham Lincoln. President Lincoln’s interest in this story was a result of the sympathy that he felt towards Mrs. Garvin and the story of her son being sold to war. Due to his sympathetic nature, on April 18, 1864, Lincoln wrote in a telegram to Colonel Paul Frank of the 52nd Potomac, the regiment in which it was believed that Cornelius was fighting. In the telegram sent from the Executive Office, Lincoln wrote, “Is there, or has there been a man in your Regiment by the name of Cornelius Garvin? And if so, answer me so far as you know where he now is.”

“Despite Lincoln’s efforts to connect Mrs. Garvin with her son, Lincoln’s telegram never received a response form Colonel Frank. However, it was suggested that Garvin’s Captain, Capt. Degner, not only neglected to search for Cornelius, but threatened his privates in aiding Mrs. Garvin, or anyone involved in the investigation with information. Colonel LC Baker placed Captain Degner under arrest until more evidence was found, but there are no further records of charges brought against Degner.”

Jane Gastineau’s chance discovery, in effect, helped solve the ages-old mystery. According to the Lincoln Library webpage, “In the summer of 1863, Cornelius Garvin (b. 1845), a resident of the Rensselaer County Almshouse, was sold as a substitute into the Union army by the home’s superintendent. Eighteen-year-old Cornelius was mentally disabled in some way and had been declared an incurable “idiot” by the Marshall Infirmary, located in Troy, N.Y. He had then been placed in the county almshouse by his mother, Catharine (d. c1896), because she could not care for him at home. When Catharine went to visit her son on September 7, 1863, the superintendent informed her that Con was in the army and showed her the money he had received as payment for the boy. Catharine wrote later, “It was very cruel to sell my idiot son.” Catharine Garvin spent the rest of the 1860s looking for Cornelius. Although he was thought to have been enlisted in the 52nd New York Infantry Regiment and an official army investigation was conducted, she never found him or learned his fate. She ultimately accepted the likelihood he was dead, as the army investigation had concluded. She applied for and received a survivor’s pension from the U.S. government. Catharine continued to live in Troy, N.Y., until around 1890 when she returned permanently to Ireland. Because she was an American citizen, she continued to receive her pension until her death in County Limerick around 1896.”

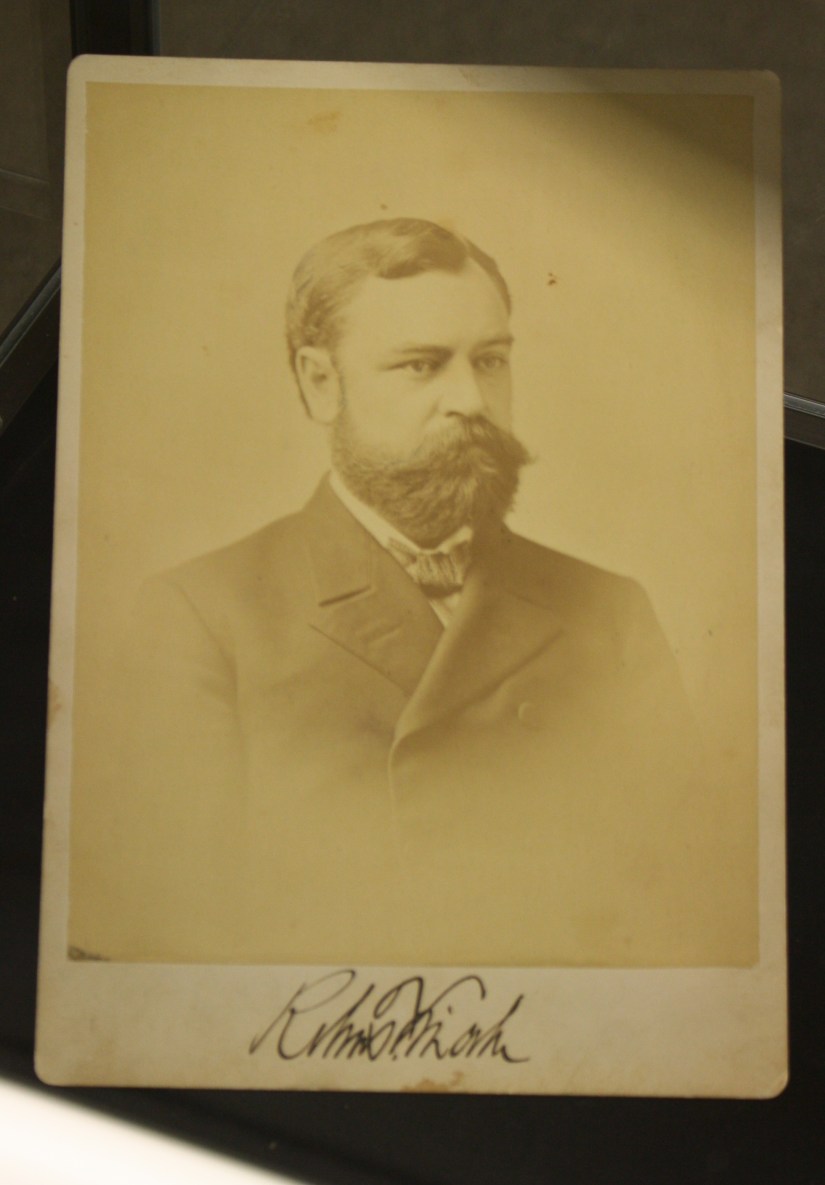

One of Jane Gastineau’s favorite observations while researching are the many “rabbit holes” she finds herself traveling through when it comes to Lincoln. The note she discovered is a perfect illustration. And those rabbit holes promise to continue for researchers long after she vacates her position. In fact, another example can be found within her research that was of particular interest to me. Col. L.C. Baker, the officer mentioned above, was none other than Lafayette Curry Baker. Baker was recalled to Washington after the 1865 assassination of President Lincoln and within two days of his arrival he and his agents had made four arrests and had the names of two more conspirators, including assassin John Wilkes Booth. Before the month was out, Booth along with Davey Herold were found holed up in a barn where Booth was shot and killed. Baker received a generous share of the Goverment’s $100,000 reward. Yes Jane, there are indeed a great many rabbit holes to explore wherever Lincoln is involved.

Photos of various Lincoln items on display in the vault at the Allen County Library.

Robert Todd Lincoln’s schoolbook.

Tad Lincoln gets a sword and a uniform per his father’s order.

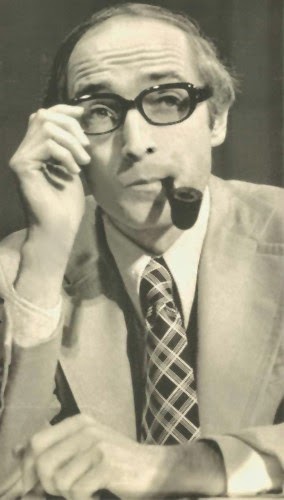

Tom Huston (derisively called “Secret Agent X-5” behind his back by some White House officials), the White House aide who devised the plan, was a young right-wing lawyer who had been hired as an assistant to White House speech writer Patrick Buchanan. Huston graduated from Indiana University in 1966 and from 1967 to 1969, served as an officer in the United States Army assigned to the Defense Intelligence Agency and was associate counsel to the president of the United States from 1969-1971.His only qualifications for his White House position were political – he had been president of the Young Americans for Freedom, a conservative campus organization nationwide.

Tom Huston (derisively called “Secret Agent X-5” behind his back by some White House officials), the White House aide who devised the plan, was a young right-wing lawyer who had been hired as an assistant to White House speech writer Patrick Buchanan. Huston graduated from Indiana University in 1966 and from 1967 to 1969, served as an officer in the United States Army assigned to the Defense Intelligence Agency and was associate counsel to the president of the United States from 1969-1971.His only qualifications for his White House position were political – he had been president of the Young Americans for Freedom, a conservative campus organization nationwide. Despite Huston’s warning that his namesake plan was illegal, Nixon approves the plan, but rejects one element-that he personally authorize any break-ins. Per Huston plan guidelines, the Internal Revenue Service began to harass left-wing think tanks and charitable organizations such as the Brookings Institution and the Ford Foundation. Huston writes that “making sensitive political inquiries at the IRS is about as safe a procedure as trusting a whore,” since the administration has no “reliable political friends at IRS.” He adds, “We won’t be in control of the government and in a position of effective leverage until such time as we have complete and total control of the top three slots of the IRS.” Huston suggests breaking into the Brookings Institute to find “the classified material which they have stashed over there,” adding: “There are a number of ways we could handle this. There are risks in all of them, of course; but there are also risks in allowing a government-in-exile to grow increasingly arrogant and powerful as each day goes by.”

Despite Huston’s warning that his namesake plan was illegal, Nixon approves the plan, but rejects one element-that he personally authorize any break-ins. Per Huston plan guidelines, the Internal Revenue Service began to harass left-wing think tanks and charitable organizations such as the Brookings Institution and the Ford Foundation. Huston writes that “making sensitive political inquiries at the IRS is about as safe a procedure as trusting a whore,” since the administration has no “reliable political friends at IRS.” He adds, “We won’t be in control of the government and in a position of effective leverage until such time as we have complete and total control of the top three slots of the IRS.” Huston suggests breaking into the Brookings Institute to find “the classified material which they have stashed over there,” adding: “There are a number of ways we could handle this. There are risks in all of them, of course; but there are also risks in allowing a government-in-exile to grow increasingly arrogant and powerful as each day goes by.”

During the question-and-answer session at that meeting, a woman stood up to relay a story of how her son was being beat up by neighborhood bullies, and how, after trying in vain to get law enforcement authorities to step in, gave her son a baseball bat and told him to defend himself. Meanwhile, the partisan crowd is chanting and cheering in sympathy with the increasingly agitated mother, and the chant: “Hooray for Watergate! Hooray for Watergate!” began to fill the room. Huston waited for the cheering to die down and says, “I’d like to say that this really goes to the heart of the problem. Back in 1970, one thing that bothered me the most was that it seemed as though the only way to solve the problem was to hand out baseball bats. In fact, it was already beginning to happen. Something had to be done. And out of it came the Plumbers and then a progression to Watergate. Well, I think that it’s the best thing that ever happened to this country that it got stopped when it did. We faced up to it…. [We] made mistakes.”

During the question-and-answer session at that meeting, a woman stood up to relay a story of how her son was being beat up by neighborhood bullies, and how, after trying in vain to get law enforcement authorities to step in, gave her son a baseball bat and told him to defend himself. Meanwhile, the partisan crowd is chanting and cheering in sympathy with the increasingly agitated mother, and the chant: “Hooray for Watergate! Hooray for Watergate!” began to fill the room. Huston waited for the cheering to die down and says, “I’d like to say that this really goes to the heart of the problem. Back in 1970, one thing that bothered me the most was that it seemed as though the only way to solve the problem was to hand out baseball bats. In fact, it was already beginning to happen. Something had to be done. And out of it came the Plumbers and then a progression to Watergate. Well, I think that it’s the best thing that ever happened to this country that it got stopped when it did. We faced up to it…. [We] made mistakes.”

In 1983, the copper was replaced with lighter, cheaper zinc- which explains why penny bending bar bets got easier to win during the Reagan years. And businesses continued to give Lincoln pennies away. Every visitor to the old Lincoln Financial Museum in Fort Wayne received a Lincoln penny in change as did visitors to the House Where Lincoln Died museum in Washington, DC during the fifties and sixties. Today, the few people who still bend over to pick them up are invariably those least able to stoop.

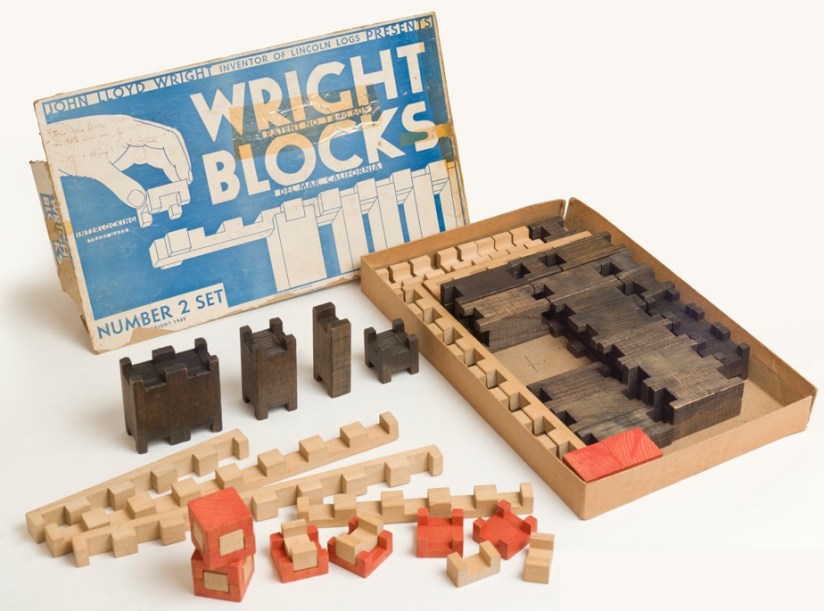

In 1983, the copper was replaced with lighter, cheaper zinc- which explains why penny bending bar bets got easier to win during the Reagan years. And businesses continued to give Lincoln pennies away. Every visitor to the old Lincoln Financial Museum in Fort Wayne received a Lincoln penny in change as did visitors to the House Where Lincoln Died museum in Washington, DC during the fifties and sixties. Today, the few people who still bend over to pick them up are invariably those least able to stoop. Lincoln Logs is a U.S. children’s toy consisting of notched miniature logs, used to build small forts and buildings. They were invented by the son of architect Frank Lloyd Wright. 24-year-old John Lloyd Wright came up with the idea for Lincoln Logs on a visit to Tokyo, Japan, while working as chief assistant for his father in 1916. John was working side-by-side with his father on the design of Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel. The foundation of the hotel was designed with interlocking log beams, making the structure one of the first “earthquake-proof” buildings in the world. The Imperial Hotel ‘s design that allowed the hotel to sway but not collapse in case of a tremor, would be one of the few buildings that remained standing after the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake that devastated Tokyo.

Lincoln Logs is a U.S. children’s toy consisting of notched miniature logs, used to build small forts and buildings. They were invented by the son of architect Frank Lloyd Wright. 24-year-old John Lloyd Wright came up with the idea for Lincoln Logs on a visit to Tokyo, Japan, while working as chief assistant for his father in 1916. John was working side-by-side with his father on the design of Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel. The foundation of the hotel was designed with interlocking log beams, making the structure one of the first “earthquake-proof” buildings in the world. The Imperial Hotel ‘s design that allowed the hotel to sway but not collapse in case of a tremor, would be one of the few buildings that remained standing after the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake that devastated Tokyo. Unlike the hotel, the relationship between father and son crumbled long before the hotel was ever completed. Suddenly out-of-work, John Lloyd Wright decided to construct a miniature model that could be used to teach children the basics of construction and engineering while encouraging imaginative play. Using the blueprint for the Imperial Hotel as a model, he created a toy construction set that consisted of notched pieces of wood that children could stack to build log cabins, forts and other rustic buildings. Unlike standard building blocks before them, the interlocking system of miniature logs could withstand the shockwaves unleashed by children’s playing roughly with the toys. When Wright created the toy, the First World War was well underway, although America had not yet entered the fray.

Unlike the hotel, the relationship between father and son crumbled long before the hotel was ever completed. Suddenly out-of-work, John Lloyd Wright decided to construct a miniature model that could be used to teach children the basics of construction and engineering while encouraging imaginative play. Using the blueprint for the Imperial Hotel as a model, he created a toy construction set that consisted of notched pieces of wood that children could stack to build log cabins, forts and other rustic buildings. Unlike standard building blocks before them, the interlocking system of miniature logs could withstand the shockwaves unleashed by children’s playing roughly with the toys. When Wright created the toy, the First World War was well underway, although America had not yet entered the fray. John Lloyd Wright organized The Red Square Toy Company (named after his father’s famous symbol), and unveiled the toy in 1918. Wright was issued U.S. patent 1,351,086 on August 31, 1920, for a “Toy-Cabin Construction”. Soon after, he changed the name to J. L. Wright Manufacturing. The original Lincoln Log set came with instructions on how to build Uncle Tom’s Cabin as well as Abraham Lincoln’s cabin. Lincoln Logs makes a lot more sense than “Uncle Tom’s” logs now doesn’t it? The instruction sheet featured a simple drawing of a log cabin, a small portrait of Lincoln and the slogan “Interesting playthings typifying the spirit of America.”

John Lloyd Wright organized The Red Square Toy Company (named after his father’s famous symbol), and unveiled the toy in 1918. Wright was issued U.S. patent 1,351,086 on August 31, 1920, for a “Toy-Cabin Construction”. Soon after, he changed the name to J. L. Wright Manufacturing. The original Lincoln Log set came with instructions on how to build Uncle Tom’s Cabin as well as Abraham Lincoln’s cabin. Lincoln Logs makes a lot more sense than “Uncle Tom’s” logs now doesn’t it? The instruction sheet featured a simple drawing of a log cabin, a small portrait of Lincoln and the slogan “Interesting playthings typifying the spirit of America.” In the 1930s, Wright attempted to build on the success of Lincoln Logs with Wright Blocks, a toy construction set with interlocking wooden shapes that allowed budding architects to build castles or other complex designs. Wright Blocks, however, proved too intricate and lacked the same appeal as Lincoln Logs. John Lloyd Wright sold his company to Playskool in 1943 for only $800. The copyright for Lincoln Logs eventually passed to toy companies Milton Bradley and Hasbro and finally, K’NEX. In 1949, a company in Denmark developed “Legos” based in large part on Wright’s original design. In February 2015, Lego replaced Ferrari as the “world’s most powerful brand”. Can you imagine, the Ghostbusters Firehouse Headquarters, Star Wars Millennium Falcon, Harry Potter’s Hogwarts Castle…all made out of Lincoln Legos? It was just that close.

In the 1930s, Wright attempted to build on the success of Lincoln Logs with Wright Blocks, a toy construction set with interlocking wooden shapes that allowed budding architects to build castles or other complex designs. Wright Blocks, however, proved too intricate and lacked the same appeal as Lincoln Logs. John Lloyd Wright sold his company to Playskool in 1943 for only $800. The copyright for Lincoln Logs eventually passed to toy companies Milton Bradley and Hasbro and finally, K’NEX. In 1949, a company in Denmark developed “Legos” based in large part on Wright’s original design. In February 2015, Lego replaced Ferrari as the “world’s most powerful brand”. Can you imagine, the Ghostbusters Firehouse Headquarters, Star Wars Millennium Falcon, Harry Potter’s Hogwarts Castle…all made out of Lincoln Legos? It was just that close.

Inside the House chamber guests listened to historian George Bancroft (former Secretary of the Navy and the man who established the Naval Academy at Annapolis) talk about “the life, character, and services of Lincoln…forming one of the most imposing scenes ever witnessed in the land.” The address took nearly two hours. The push for a formal celebration quickly spread to state capitals, legislatures and city councils. Most northern states quickly warmed to the idea but bitterness over Reconstruction and the cult of the “Lost Cause” among southerners scuttled attempts to make Lincoln’s birthday a Federal holiday.

Inside the House chamber guests listened to historian George Bancroft (former Secretary of the Navy and the man who established the Naval Academy at Annapolis) talk about “the life, character, and services of Lincoln…forming one of the most imposing scenes ever witnessed in the land.” The address took nearly two hours. The push for a formal celebration quickly spread to state capitals, legislatures and city councils. Most northern states quickly warmed to the idea but bitterness over Reconstruction and the cult of the “Lost Cause” among southerners scuttled attempts to make Lincoln’s birthday a Federal holiday. In 1971 Congress passed the Uniform Monday Holiday Act. The law shifted several holidays (Veteran’s Day, Washington’s Birthday, Memorial Day, Labor Day, Lincoln’s Birthday and Columbus Day to name a few) from specific days to a Monday. The reason behind the change was seen as a way to create more three-day weekends and reduce employee absenteeism. The birthdays of George Washington and Lincoln were only 10 days apart, so they were blended into Presidents’ Day.

In 1971 Congress passed the Uniform Monday Holiday Act. The law shifted several holidays (Veteran’s Day, Washington’s Birthday, Memorial Day, Labor Day, Lincoln’s Birthday and Columbus Day to name a few) from specific days to a Monday. The reason behind the change was seen as a way to create more three-day weekends and reduce employee absenteeism. The birthdays of George Washington and Lincoln were only 10 days apart, so they were blended into Presidents’ Day. Eventually, individual states created their own Presidents’ Day holidays to be observed on the third Monday in February. This celebration has been enacted in some fashion by 38 states, though never federally, and each varies by state. Some mark the day as a specific remembrance of Washington and Lincoln while others view it as a day to recognize all U.S. presidents. Alabama celebrates Washington and Jefferson. A few states still recognize Lincoln’s birthday on February 12 as its own official holiday. Most notably, Kentucky, his birth state and Illinois,his adopted home state, both celebrate Lincoln’s birthday as an official state holiday, along with a few other states including New York, Connecticut, and Missouri. However, this number has declined in recent years, when California, Ohio and New Jersey ended the celebration of Lincoln’s birthday as paid holidays to cut budgetary costs. Unfortunately, more states now celebrate Black Friday as a holiday than celebrate Lincoln’s birthday. Indiana and Georgia are a couple states that recognize Lincoln’s Birthday on the day after Thanksgiving aka Black Friday.

Eventually, individual states created their own Presidents’ Day holidays to be observed on the third Monday in February. This celebration has been enacted in some fashion by 38 states, though never federally, and each varies by state. Some mark the day as a specific remembrance of Washington and Lincoln while others view it as a day to recognize all U.S. presidents. Alabama celebrates Washington and Jefferson. A few states still recognize Lincoln’s birthday on February 12 as its own official holiday. Most notably, Kentucky, his birth state and Illinois,his adopted home state, both celebrate Lincoln’s birthday as an official state holiday, along with a few other states including New York, Connecticut, and Missouri. However, this number has declined in recent years, when California, Ohio and New Jersey ended the celebration of Lincoln’s birthday as paid holidays to cut budgetary costs. Unfortunately, more states now celebrate Black Friday as a holiday than celebrate Lincoln’s birthday. Indiana and Georgia are a couple states that recognize Lincoln’s Birthday on the day after Thanksgiving aka Black Friday. In most states, Lincoln’s birthday is not celebrated separately, as a stand-alone holiday. Instead Lincoln’s Birthday is combined with a celebration of President George Washington’s birthday (also in February) and celebrated either as Washington’s Birthday or as Presidents’ Day on the third Monday in February, concurrent with the federal holiday. Good for George Washington. Sad for Abraham Lincoln. Once upon a time, Lincoln’s birthday was a milestone for Americans to pause and honor greatness.

In most states, Lincoln’s birthday is not celebrated separately, as a stand-alone holiday. Instead Lincoln’s Birthday is combined with a celebration of President George Washington’s birthday (also in February) and celebrated either as Washington’s Birthday or as Presidents’ Day on the third Monday in February, concurrent with the federal holiday. Good for George Washington. Sad for Abraham Lincoln. Once upon a time, Lincoln’s birthday was a milestone for Americans to pause and honor greatness.