Original publish date: March 31, 2017

Original publish date: March 31, 2017

History just happens. Often, history is well planned, scheduled and expected. The history I have always found most appealing is that which was unplanned, unscheduled and unexpected. Examples: Gettysburg, Woodstock, and Robert F. Kennedy’s April 4, 1968 speech in Indianapolis. True, the soldiers were gonna fight, the bands were gonna rock and RFK was gonna give a speech, but history happened far beyond the participants’ wildest imaginations. The prologue and aftermath, those always intrigued me the most.

For example, the Loraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. Historians recognize the name as the site of the assassination of Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. But what about the Lorraine Motel before and after that tragic night? The Lorraine Motel, located at 450 Mulberry Street, in downtown Memphis, first opened its doors in 1925. The 16-room one-story all-white establishment was first known as the Windsor Hotel and stood just six blocks east of the Mississippi River. When the hotel first opened, Memphis was fast becoming a music hotspot with Beale Street as a mecca for Delta blues fans. Machine Gun Kelly roamed the streets, Cotton was king and Democratic Party Boss Crump ran the city like a well oiled machine.

The Windsor served businessmen, musicians and tourists until the closing days of World War II when it underwent a name change to the Marquette Hotel. In 1945, the hotel was purchased by minority businessman Walter Bailey, who renamed the hotel “Lorraine” to honor his wife Loree and his favorite song “Sweet Lorraine” by Nat King Cole. During the segregation era, Bailey re-branded the hotel as upscale lodging that catering to black clientele. At the time of purchase the Lorraine included 16 rooms, a café, and living quarters for the Baileys.

The Baileys added a second floor with 12 rooms, a swimming pool, and drive-up access for more rooms on the south side of the complex. The Baileys added even more guest rooms and drive-up access, transforming it from a hotel into a motel. Under the Baileys’ ownership, the Lorraine Motel became a safe haven for black travelers in the Jim Crow South. The motel was listed in “The Negro Motorist Green Book,” also known as the Green Guide, a compilation of hotels, restaurants, gas stations, beauty parlors, barber shops, and other businesses that were friendly to African-Americans during the segregation era.

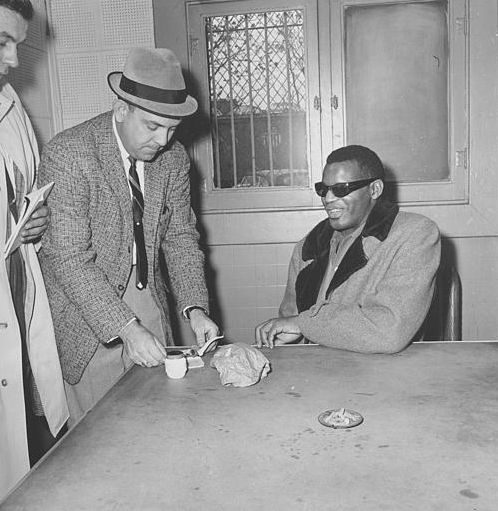

As lackluster as those old guest registers from the Windsor must have been in the hotel’s first two decades, Bailey’s Lorraine became star studded and the registers must have read like a who’s who of black celebrities. With the 1957 opening of Stax Records, less than 3 miles away, the Lorraine became the preferred home away from home for some of the biggest names in the music business: Ray Charles, Lionel Hampton, Aretha Franklin, Ethel Waters, Otis Redding, Cab Calloway, Count Basie, Louis Armstrong, Sarah Vaughan, the Staple Singers and Wilson Pickett to name just a few. The Lorraine was even visited by the Bailey’s favorite singer Nat King Cole on several occasions.

The motel’s proximity to Beale Street attracted black songwriters and session musicians would stay at the Lorraine while they were recording in Memphis. Negro League baseball teams, in town to play the Memphis Red Sox, and the Harlem Globetrotters also spent time at the motel. Although officially categorized as a segregated hotel, the Baileys welcomed both black and white guests. The Lorraine became equally famous its home-cooked meals, Memphis barbecue, and upscale environment at affordable rates (under $13 a night).

Stax recording artist Isaac Hayes, best remembered by baby boomers for his classic theme from “Shaft”, former owner of the old ABA Memphis Tams and as his character “Chef” from South Park, was a frequent guest of the Lorraine Motel back in the day. He once said this of the historic motel, “We’d go down to the Lorraine Motel and we’d lay by the pool and Mr. Bailey would bring us fried chicken and we’d eat ice cream. . . . We’d just frolic until the sun goes down and [then] we’d go back to work.” Two famous songs, Wilson Pickett’s “In the Midnight Hour” and Eddie Floyd’s “Knock on Wood,” were written at the motel.

Steve Cropper, a white Stax record guitarist with Booker T & the MG’s, co-wrote both songs with the artists while staying at the Loraine. He has stated in interviews that there was a lightning storm the night that he and Eddie wrote the song, hence the lyrics ‘It’s like thunder and lightning, The way you love me is frightening’. When Sam & Dave shout “Play It Steve” in their hit song “Soul Man”, they’re talking about Cropper. Other prominent guests included Brooklyn Dodgers stars Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella.

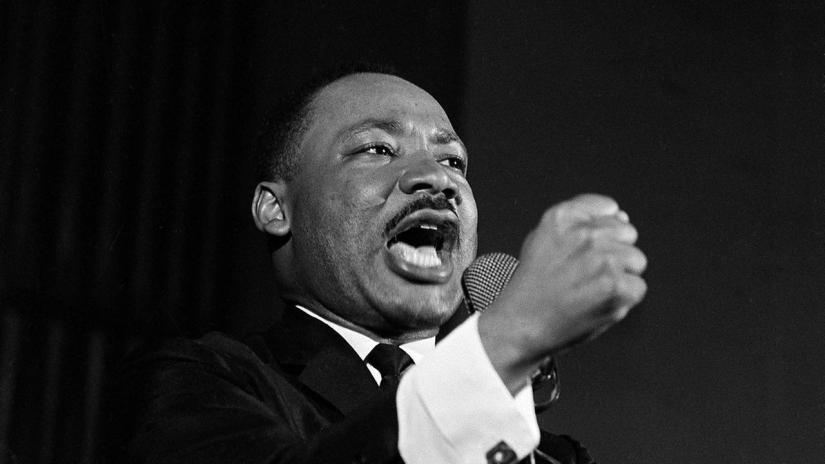

However, Martin Luther King, Jr., was the Lorraine Motel’s most famous guest. It was Dr. King’s preferred residence while visiting the city. Dr. King and Rev. Ralph Abernathy had stayed together at the Lorraine several times, sharing Room 306 so often that they jokingly called it “the King-Abernathy suite” when phoning in reservations. His last visit was in the spring of 1968, when he came to Memphis to support 1,300 striking sanitation workers. Their grievances included unfair working conditions: when it rained, black workers were sent home without pay while paid white supervisors remained on the job, black workers were given only one uniform and no place in which to change clothes, and poor pay capped at a fraction of the pay for white workers doing the same jobs. Following a bloody confrontation between marching strikers and police, a court injunction had been issued banning further protests. King hoped to lead a peaceful protest march aimed at overturning the court injunction.

Dr. King had stayed at the Lorraine on March 18, when he spoke to an enormous crowd at the Mason Temple Church of God in Christ in support of the striking sanitation workers. The venue was perhaps the largest meeting space for African Americans in the South and a good fit for King’s Poor People’s Campaign. As King called for a general work the crowd (estimated at 12-14,000 people) erupted in cheers and foot-stomping.

Dr. King had stayed at the Lorraine on March 18, when he spoke to an enormous crowd at the Mason Temple Church of God in Christ in support of the striking sanitation workers. The venue was perhaps the largest meeting space for African Americans in the South and a good fit for King’s Poor People’s Campaign. As King called for a general work the crowd (estimated at 12-14,000 people) erupted in cheers and foot-stomping.

King returned to Memphis a week later to lead a protest march on City Hall. That day turned out to be one of the worst in King’s career. The marchers paraded down Beale Street with Dr. King was at the head of the column. When they turned onto Main Street, they were greeted by police in riot gear blocking their way. Dr. King reluctantly turned around. Then, police attacked with tear gas and billy clubs. One marcher was shot to death. Dozens of protesters were injured and nearly 300 arrested. Stores were looted and burned. The whole sad affair was captured on film and broadcast on television. Soon, Memphis became an armed camp and martial law was the rule of the day.

Dr. King quickly planned a return visit six days later to blot this stain off the civil rights landscape. That morning, King’s plane from Atlanta was delayed by a bomb threat; no explosive was found. King spent the better part of the day, April 3, meeting with aides and local organizers at the Lorraine Motel. He was exhausted and feeling ill. A heavy storm rumbled in and raged on and off all day long. That evening, Mason Temple had scheduled Rev. Abernathy as the evening speaker, but when the 3,000 person crowd demanded to hear King, Abernathy phoned King at his room in the Lorraine and asked him to address the assembly.

Dr. King arrived as the storm rattled windows and rain beat down on the metal roof of the Temple. Dr. King stepped to the podium and delivered his prophetic “Mountaintop” speech that night. It would be the last speech of his life. He closed with the eerily prophetic lines, “I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place.But I’m not concerned about that now… I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you… And so I’m happy, tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man! Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord!”

King spent April 4, 1968, the last day of his life, at the Lorraine Motel. He shared a plate of fried Mississippi River catfish with Rev. Abernathy for his final meal. Afterwards, Dr. King participated in a playful pillow fight with Abernathy and aide Andrew Young. Just after 6 p.m., Dr. King stepped out of Room 306 and conversed with Jesse Jackson in the parking lot below. He leaned over the metal railing and asked the saxophonist Ben Branch to play “Take My Hand, Precious Lord” , one of King’s personal favorites, at the rally that evening. As King wondered aloud whether he needed a topcoat and turned back towards his room, a sharp sound rang out. Some thought it was a firecracker, or a car backfiring. Martin Luther King Jr. had been shot in the face. He died shortly afterwards at a hospital.

King spent April 4, 1968, the last day of his life, at the Lorraine Motel. He shared a plate of fried Mississippi River catfish with Rev. Abernathy for his final meal. Afterwards, Dr. King participated in a playful pillow fight with Abernathy and aide Andrew Young. Just after 6 p.m., Dr. King stepped out of Room 306 and conversed with Jesse Jackson in the parking lot below. He leaned over the metal railing and asked the saxophonist Ben Branch to play “Take My Hand, Precious Lord” , one of King’s personal favorites, at the rally that evening. As King wondered aloud whether he needed a topcoat and turned back towards his room, a sharp sound rang out. Some thought it was a firecracker, or a car backfiring. Martin Luther King Jr. had been shot in the face. He died shortly afterwards at a hospital.

The world, and the Lorraine Motel, would never be the same.

Original publish date: November 5, 2014

Original publish date: November 5, 2014 Original publish date: April 3, 2016

Original publish date: April 3, 2016 Original publish date: May 27, 2016

Original publish date: May 27, 2016 Original publish date: November 19, 2008

Original publish date: November 19, 2008