Original publish date: June 8, 2015

Original publish date: June 8, 2015

I lost a favorite uncle last month. David A. McDuffee was my mother’s brother and a helluva man. He graduated from Ben Davis High School in 1958, as did my mom two years before him. He was a fixture in my life for as long as I can remember. I have fond memories of my Uncle Dave driving all the way from Avon to watch me play basketball all through my high school years. Then doing the same later in my life to watch high school baseball games while I was coaching. That’s just the kind of guy he was.

During his final ride to Boggstown cemetery, I couldn’t help but smile when the procession stopped for several minutes along a Shelby County road. The family had wisely decided to transfer the casket onto a hay wagon pulled by an old Farmall tractor for the final leg of his trip to the cemetery. It was my uncle’s tractor. As I recall, he named the thing Millard or Wilbur or something like that. He’d forgive me for getting the name wrong. He was not a farmer, he was a retired National Guardsman, faithful husband and loving grandfather…and uncle. He just wanted a tractor. That was my Uncle Dave.

At the cemetery, after the service, I wandered over to that tractor and gave it a good rub in his honor. In particular the steering wheel. All the while I was thinking about a memory from my childhood. My first car was a 1967 Mercury Comet. My grandfather had gone to a used car lot with my mom (his daughter) and purchased it when I was 16 years old. Before it was delivered I remember asking them to describe it and I recall my grandfather saying, “Well, it’s sporty.” (It wasn’t) But what made that car special to me was something my Uncle Dave had attached to the steering wheel. It was a suicide knob with a brightly colored 7-Up logo on it. My uncle worked at 7-up on Indy’s eastside for many years. He was a delivery driver and the suicide knob was a holdover relic from his years behind the wheel. I didn’t need it, that ’67 Mercury Comet had power steering, but I loved it just the same.

Don’t remember suicide knobs? Well, maybe you called them spinners, granny knobs, brodie knobs or “necker knobs”. They were usually made of plastic, rubber or bakelite and attached to the steering wheel by a metal bracket. They were most popular in the 1950s and 1960s in the age before power steering ruled the roads. These knobs enabled the driver to steer the wheel with one hand, freeing up the other hand for more important stuff. The term “necker knobs” came about when it was discovered that the driver could steer his car one-handed and wrap his free arm around his girlfriend, who was usually resting her head on the driver’s shoulder.

Although they were primarily designed for trucks and tractors, like fuzzy dice hanging from the rear view mirror, they quickly became a groovy accessory for hipsters all over the Circle City. The West Coast hot-rodders were the first to jump on the suicide knob bandwagon. Easy to grip, the knob was used to spin the steering wheel in one direction or the other while accelerating to cause the wheels to spin while whipping the car 180 degrees, or “half a donut.” West Coast hot-rodders called this maneuver “spinning a brodie.”

Back in the day, you could walk into any auto parts store in the city and choose from a wide array of these steering wheel knobs of every conceivable size and style. There were shiny chrome ones, Candy Apple or Orange Crush colored ones, product logos and, gulp, scantily clad women suicide knobs. If you were lucky, you might even score a free one from the auto parts store itself or some other transportation related company. Alas, unless you stumble across one at an antique shop or flea market, you never see suicide knobs anymore.

I loved that old 7-Up suicide knob but it did not come without its own built-in pitfalls. The knob itself was designed to spin in the drivers hand which sometimes caused it to slip out of your grip. Another disadvantage of the knob was that after turning a sharp corner and letting go, the steering wheel would spin rapidly causing the knob to hit the driver’s forearm or elbow. Or worse catching on loose clothing or jewelry. But no doubt about it, suicide knobs just flat out looked cool.

Brodie knobs (named for Steve Brodie, a New York City daredevil who jumped off the Brooklyn Bridge and survived on July 23, 1886.), have all but disappeared from cars today. But there was a time when every James Dean wannabe had one hand on the suicide knob and the other hand on his girlfriend. They were as much a part of the street scene as leather jackets, Brylcreemed ducktail hair and a pack of cigarettes rolled up in a t-shirt sleeve.

Most baby boomers grew up thinking that the Department of Transportation outlawed them in most states decades ago. But wait, that’s not true! More than likely, that rumor was started by concerned mothers and fathers to keep teenagers from buying them. There is no way of knowing, but that urban legend of a ban probably closely followed the coining of the term “Suicide Knob.” In truth, Brodie knobs are legal on private vehicles in most U.S. states. In New York State, a doctor’s prescription must be submitted to the New York State Department of Motor Vehicles, which in turn, shows that the knob is “required” on all vehicles the user drives and such requirement is entered on the user’s drivers license. You say you want a Brody knob on your steering wheel? Go right ahead, it’s legal in Indiana and you don’t even need a doctor’s note.

Their main use today is still in trucks, particularly 18-wheelers, where they allow simultaneous steering and operation of the radio or gearshift. They are also used on forklifts and riding lawnmowers, where frequent sharp turning is required. The knob is also standard equipment in most modern farm and commercial tractors, its main purpose being to ease single-hand steering while the driver operates other controls with his/her other hand or is traveling in reverse. Go on a gator excursion in Florida or Louisiana, you’ll most likely find one on the ship’s wheel. It’s a perfect way for captains to steer the boat with one hand and feed the gators with the other. Bringing new meaning to the term “Suicide knob.”

Over my years haunting roadside flea markets, antique malls and shows and yard sales, I have seen many different styles of suicide knobs offered for sale. Most of them have been well-used dull earth colored relics unworthy of comment until picked up and identified as a relic from the road. But others resonate in my memory like the 1939 World’s Fair version I saw many years ago. Or pin-ups like Bettie Page, Jayne Mansfield and Marilyn Monroe. Some were clear topped knobs containing pictures of long lost girlfriends or family members. But just as many bore familiar images like the Pep Boys, Sears, Skulls, Billiard balls, Mopar and every make and model of automobile you can imagine.

The manufacturers names that can be found on these knobs are unfamiliar to all but the most dedicated gearhead: Casco, Fulton, Morton and Santay among others. As fas as I can tell, suicide knobs are an invention unique to the United States. I’ve yet to find one from another country. I believe the VW version I once saw was produced for the American market. But I have my suspicion now that Cuba’s borders are opening up, we might find that the suicide knob is alive and well in that Caribbean time capsule. If you’re lucky, you can pick up a vintage suicide knob for ten bucks or less, but some of them command several hundred dollars each.

The manufacturers names that can be found on these knobs are unfamiliar to all but the most dedicated gearhead: Casco, Fulton, Morton and Santay among others. As fas as I can tell, suicide knobs are an invention unique to the United States. I’ve yet to find one from another country. I believe the VW version I once saw was produced for the American market. But I have my suspicion now that Cuba’s borders are opening up, we might find that the suicide knob is alive and well in that Caribbean time capsule. If you’re lucky, you can pick up a vintage suicide knob for ten bucks or less, but some of them command several hundred dollars each.

A search of the internet revels that suicide knobs are being reproduced and newly produced for car guys today. However, whether they are for use or display, I cannot say. You can still find them at truckstops, but then again nowadays you can find anything at a truckstop. There is a USA Federal OSHA labor law restricting their use for specific construction vehicles, mostly those vehicles hauling chemicals and potentially unstable loads. They are a staple, and in some states mandated, for use by drivers with physical limitations.

So in this “everything old is new again” retro world we live in, suicide knobs may be making a comeback. But in this age of power steering, smart phones and texting, the suicide knob will probably remain a novelty. As for that 1967 Mercury Comet of mine, it was stolen when I was in high school and I never saw it again. I don’t miss that car, but I sure miss that suicide knob. And I miss my Uncle Dave.

Original publish date: July 11, 2016

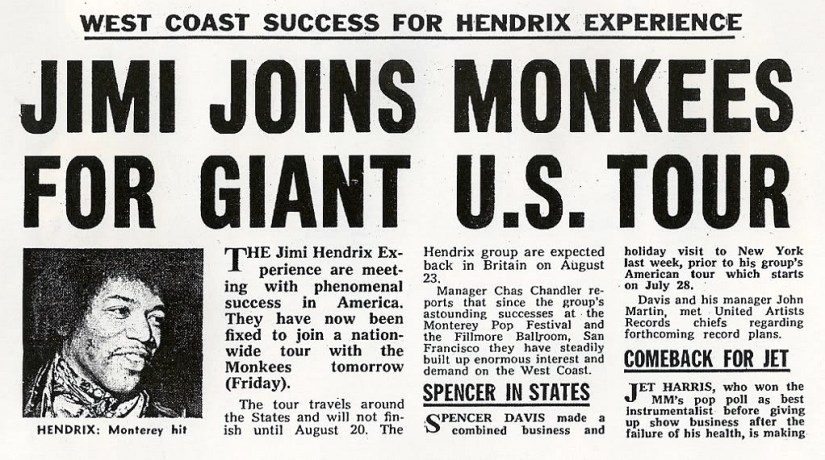

Original publish date: July 11, 2016 Jimi joined the tour on July 8 in Jacksonville, Florida, after The Monkees returned from three gigs in England. Now, imagine being a Monkees-loving teenager wedged into a sweaty, darkened, cram-packed concert hall anticipating the arrival of your favorite TV-pop band. Wearing your Monkees bubblegum machine pins, flipping through your official Monkees trading cards and holding your hand lettered poster professing your love for one Monkee or another. The curtain rises and this new guy Jimi Hendrix storms the stage to melt your face off while playing the guitar with his teeth!

Jimi joined the tour on July 8 in Jacksonville, Florida, after The Monkees returned from three gigs in England. Now, imagine being a Monkees-loving teenager wedged into a sweaty, darkened, cram-packed concert hall anticipating the arrival of your favorite TV-pop band. Wearing your Monkees bubblegum machine pins, flipping through your official Monkees trading cards and holding your hand lettered poster professing your love for one Monkee or another. The curtain rises and this new guy Jimi Hendrix storms the stage to melt your face off while playing the guitar with his teeth!

The Jimi Hendrix Experience experiment lasted just eight of the 29 scheduled tour dates. After only a few gigs, Hendrix grew tired of the “We want the Monkees” chant that met his every performance. Matters came to a head a few days later as the Monkees played a trio of dates in New York. On Sunday July 16, 1967, Jimi flipped off the audience at Forest Hills Stadium in Queens, threw down his guitar and walked off stage, leaving Monkeemania forever in his wake. After all, “Purple Haze” and Are You Experienced? were climbing the American charts, and it was time for him play for audiences who wanted to see him. He asked to be let out of his contract, and he and the Monkees amicably parted ways.

The Jimi Hendrix Experience experiment lasted just eight of the 29 scheduled tour dates. After only a few gigs, Hendrix grew tired of the “We want the Monkees” chant that met his every performance. Matters came to a head a few days later as the Monkees played a trio of dates in New York. On Sunday July 16, 1967, Jimi flipped off the audience at Forest Hills Stadium in Queens, threw down his guitar and walked off stage, leaving Monkeemania forever in his wake. After all, “Purple Haze” and Are You Experienced? were climbing the American charts, and it was time for him play for audiences who wanted to see him. He asked to be let out of his contract, and he and the Monkees amicably parted ways. Original publish date: December 18, 2016

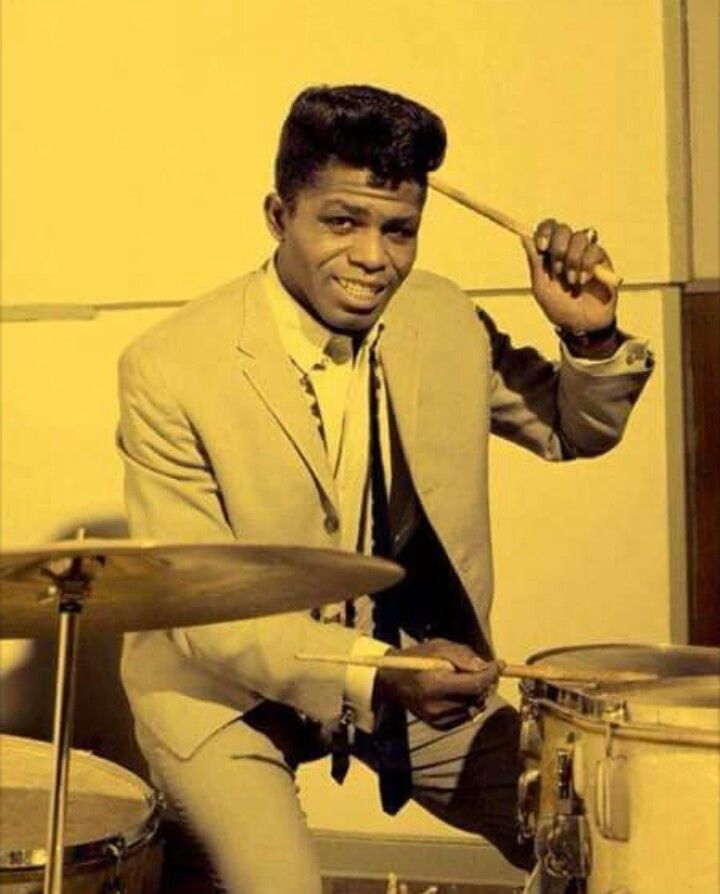

Original publish date: December 18, 2016 By 1968, James Brown was much more than an important musician; he was an African-American icon. He often spoke publicly about the pointlessness of rioting. In February 1968, Soul Brother No. 1 informed Black Panther leader H. Rap Brown, “I’m not going to tell anybody to pick up a gun.” Brown often canceled his shows to perform benefit concerts for black political organizations like the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). In 1968, he initiated “Operation Black Pride,” and, dressing as Santa Claus, presented 3,000 certificates for free Christmas dinners in New York City’s poorest black neighborhoods. He also started buying radio stations.

By 1968, James Brown was much more than an important musician; he was an African-American icon. He often spoke publicly about the pointlessness of rioting. In February 1968, Soul Brother No. 1 informed Black Panther leader H. Rap Brown, “I’m not going to tell anybody to pick up a gun.” Brown often canceled his shows to perform benefit concerts for black political organizations like the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). In 1968, he initiated “Operation Black Pride,” and, dressing as Santa Claus, presented 3,000 certificates for free Christmas dinners in New York City’s poorest black neighborhoods. He also started buying radio stations. Except for a brief period during the mid-1960s when Brown wore his hair in a traditional afro as a temporary form of protest, for most of his career, James Brown had his hair “marceled” aka straightened or conked. The conk (derived from congolene, a hair straightener gel made from lye) was a hairstyle popular among African-American men. This hairstyle transformed naturally “kinky” hair by chemically straightening it with a relaxer (sometimes the pure corrosive chemical lye), so that the newly straightened hair could be styled in specific ways.

Except for a brief period during the mid-1960s when Brown wore his hair in a traditional afro as a temporary form of protest, for most of his career, James Brown had his hair “marceled” aka straightened or conked. The conk (derived from congolene, a hair straightener gel made from lye) was a hairstyle popular among African-American men. This hairstyle transformed naturally “kinky” hair by chemically straightening it with a relaxer (sometimes the pure corrosive chemical lye), so that the newly straightened hair could be styled in specific ways. Original publish date: June 26, 2014

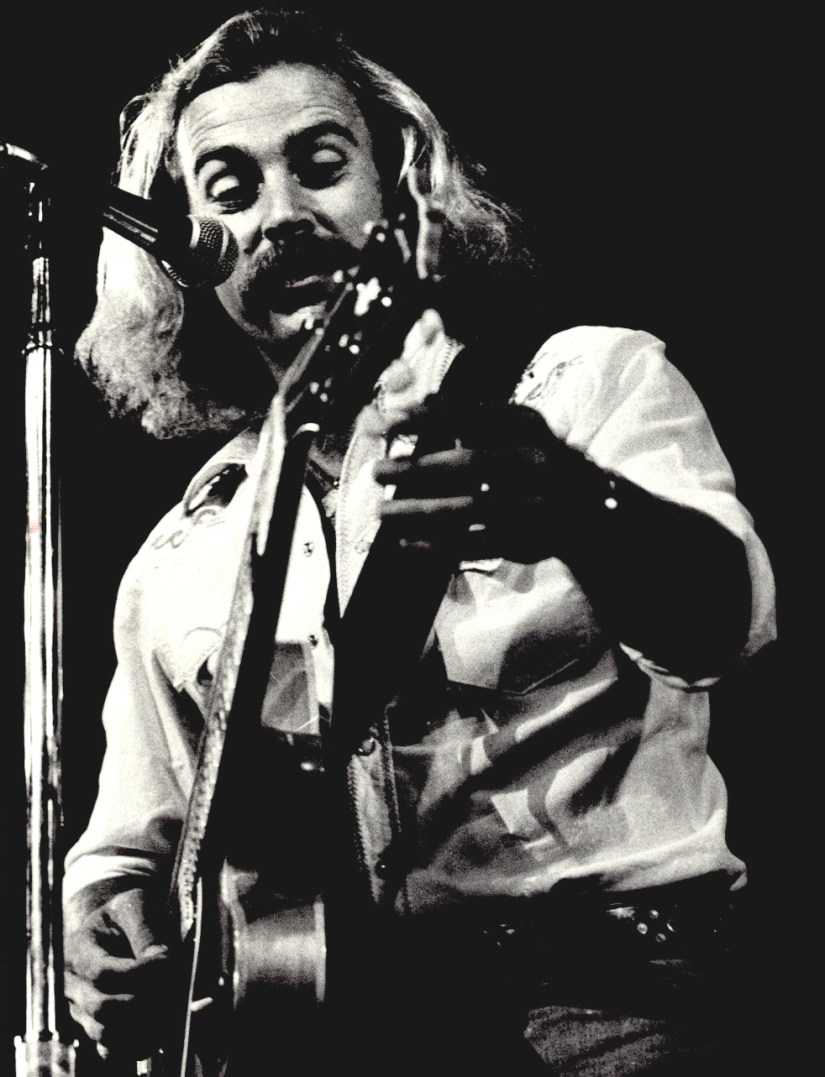

Original publish date: June 26, 2014 Buffett himself tells the story on his fan website, in a 1975 interview for Rolling Stone and in his own biography. “We’re there dining and dancing. Sammy Creason (Drummer) was with me (other accounts say Kris Kristofferson’s bass player Terry Paul was there too), so we provided just a gala of entertainment. Me on acoustic guitar so drunk I couldn’t hit the chords and him just pounding the drums out in 3-quarter time. Ran everybody out. We got the screaming munchies and we were going to Charlie Nickens to eat. And I couldn’t find my rent-a-car, which was parked somewhere amidst thousands of cars in the parking lot of the fabulous, plush King of the Road hotel. It was a little bitty car. It was hiding among many big ones there. And there was a Tennessee Prosecutors convention going on there. If they had made it to room 819 they would’ve had a closed door case.

Buffett himself tells the story on his fan website, in a 1975 interview for Rolling Stone and in his own biography. “We’re there dining and dancing. Sammy Creason (Drummer) was with me (other accounts say Kris Kristofferson’s bass player Terry Paul was there too), so we provided just a gala of entertainment. Me on acoustic guitar so drunk I couldn’t hit the chords and him just pounding the drums out in 3-quarter time. Ran everybody out. We got the screaming munchies and we were going to Charlie Nickens to eat. And I couldn’t find my rent-a-car, which was parked somewhere amidst thousands of cars in the parking lot of the fabulous, plush King of the Road hotel. It was a little bitty car. It was hiding among many big ones there. And there was a Tennessee Prosecutors convention going on there. If they had made it to room 819 they would’ve had a closed door case. I was not scared of this individual. I just thought he was some ex-football player turned counselor. And Sammy said “look whatever damage we did ABC will pay for everything” which was awfully generous of Sammy since he didn’t have the authority to say so. Being a good company man I took up for my company and said “No they won’t. I’m still gonna beat your a*s if you don’t leave us alone”. With that he pulled up then stuck his big head and his hand in and grabbed me by my hair until it separated from my head. I had a big bald spot on the back of it and I looked like a monk for about 3 months. Then he punched Sammy right in the nose. We knew he wasn’t kidding. So Sammy defended himself bravely with a bic pen. He starts stabbing at this man’s arm trying to get it out of the window because we couldn’t start the car because with the new modern features of ‘74 automobiles you can not start your car unless your seat belt’s buckled and we were too drunk to get ours hooked up.

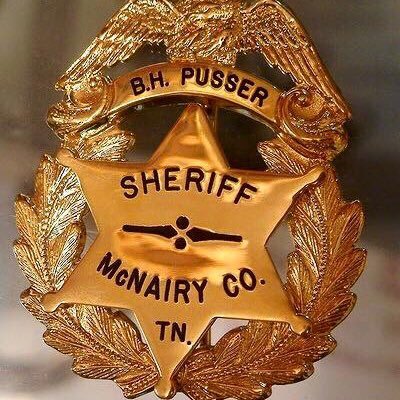

I was not scared of this individual. I just thought he was some ex-football player turned counselor. And Sammy said “look whatever damage we did ABC will pay for everything” which was awfully generous of Sammy since he didn’t have the authority to say so. Being a good company man I took up for my company and said “No they won’t. I’m still gonna beat your a*s if you don’t leave us alone”. With that he pulled up then stuck his big head and his hand in and grabbed me by my hair until it separated from my head. I had a big bald spot on the back of it and I looked like a monk for about 3 months. Then he punched Sammy right in the nose. We knew he wasn’t kidding. So Sammy defended himself bravely with a bic pen. He starts stabbing at this man’s arm trying to get it out of the window because we couldn’t start the car because with the new modern features of ‘74 automobiles you can not start your car unless your seat belt’s buckled and we were too drunk to get ours hooked up. If you don’t recognize the name Buford Pusser, the epic films made about his life might ring a bell. Buford Hayse Pusser was the Sheriff of McNairy County, Tennessee from 1964 to 1970 and the subject of the film “Walking Tall”. Pusser, a 6 feet 6 inch tall 250 pound former professional wrestler, became known for his virtual one-man war on moonshining, prostitution, gambling, and other vices on the Mississippi-Tennessee state-line against the Dixie Mafia and the State Line Mob. By the time he encountered Buffett, Pusser had already killed two men.

If you don’t recognize the name Buford Pusser, the epic films made about his life might ring a bell. Buford Hayse Pusser was the Sheriff of McNairy County, Tennessee from 1964 to 1970 and the subject of the film “Walking Tall”. Pusser, a 6 feet 6 inch tall 250 pound former professional wrestler, became known for his virtual one-man war on moonshining, prostitution, gambling, and other vices on the Mississippi-Tennessee state-line against the Dixie Mafia and the State Line Mob. By the time he encountered Buffett, Pusser had already killed two men. Original publish date: April 7, 2017

Original publish date: April 7, 2017

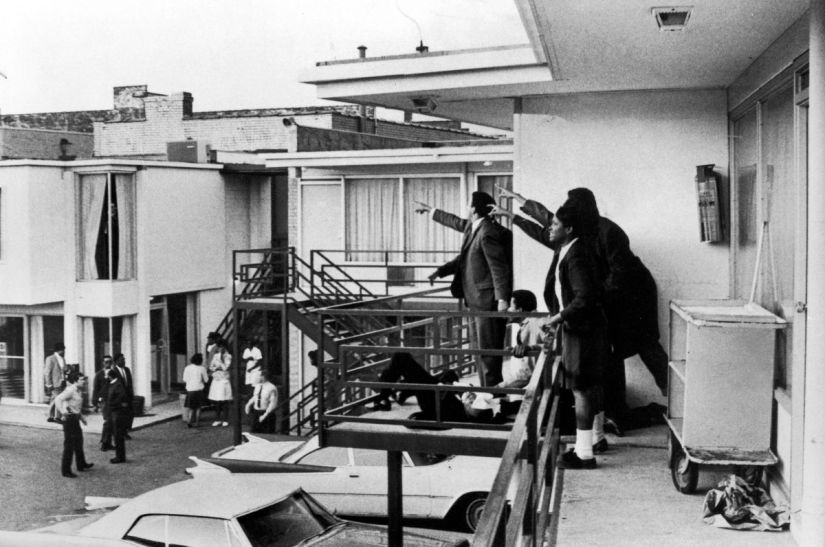

Jacqueline believed the Lorraine should be used for helping the poor and needy, rather than a celebration of Dr. King’s death. She told visitors that “Memphis has always been a city where the two biggest attractions are memorials to two dead men: Martin Luther King, Jr. and Elvis Presley.” Near Smith’s perch was a sign that read, “Stop worshiping the dead.” Smith argued that Dr. King’s legacy would have been better honored by converting the motel into low-income housing or a facility for the poor. “It’s a tourist trap, first and foremost… this sacred ground is being exploited.” Smith said of the museum that she never set foot in, despite invitations from the museum staff to do so. Smith’s call for a boycott has gone largely unheeded and she maintains her vigil outside the Loraine to this day.

Jacqueline believed the Lorraine should be used for helping the poor and needy, rather than a celebration of Dr. King’s death. She told visitors that “Memphis has always been a city where the two biggest attractions are memorials to two dead men: Martin Luther King, Jr. and Elvis Presley.” Near Smith’s perch was a sign that read, “Stop worshiping the dead.” Smith argued that Dr. King’s legacy would have been better honored by converting the motel into low-income housing or a facility for the poor. “It’s a tourist trap, first and foremost… this sacred ground is being exploited.” Smith said of the museum that she never set foot in, despite invitations from the museum staff to do so. Smith’s call for a boycott has gone largely unheeded and she maintains her vigil outside the Loraine to this day.