Original publish date: December 5, 2019

Politics. No matter where you go, you can’t escape it. No doubt last week Thanksgiving tables all across the Hoosier state either artfully dodged or spiritedly discussed politics in one form or another. Luckily, if you don’t like the political situation in this country, you can do your part to change it by exercising your right to vote. But what about the influence wielded by those most powerful “influencers” who never ran for office nor received a single vote? I’m not talking about the Kardashians, Oprah, Ellen or Taylor Swift. They may influence style and pop culture, but they do not steer public policy.

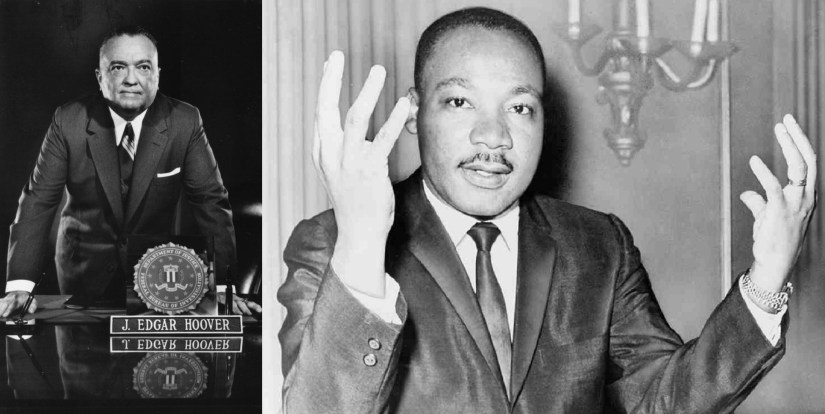

An argument could be made that today we are living within the most powerful unelected government in history of the United States. I would imagine that the average citizen could name more unelected policy influencers than they could legislators. Doubt that? Names like Buffet, Gates, Zuckerberg, the Koch Brothers, Limbaugh, Hannity, Maher, O’Reilly, Soros, Bezos, Musk ring a bell? However, any child of the sixties would counter those examples with names like Dylan, Lennon, Leary, Ali, Malcolm X, and Chavez. The difference is that today’s policy influencers attempt change through money while baby boomer influencers attempted change through ideals. In the case of the sixties, the two most powerful unelected influencers came from opposite ends of the spectrum. They were FBI leader J. Edgar Hoover and Civil Rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

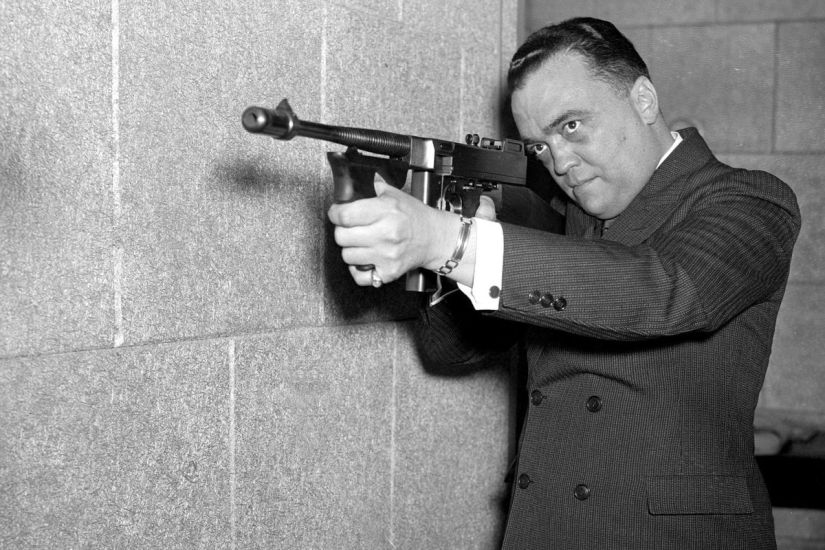

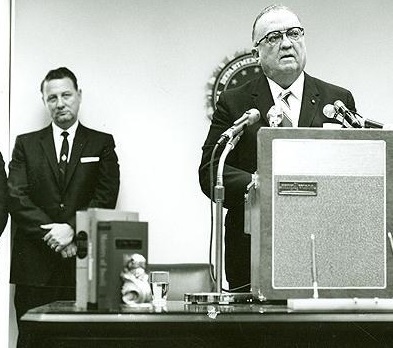

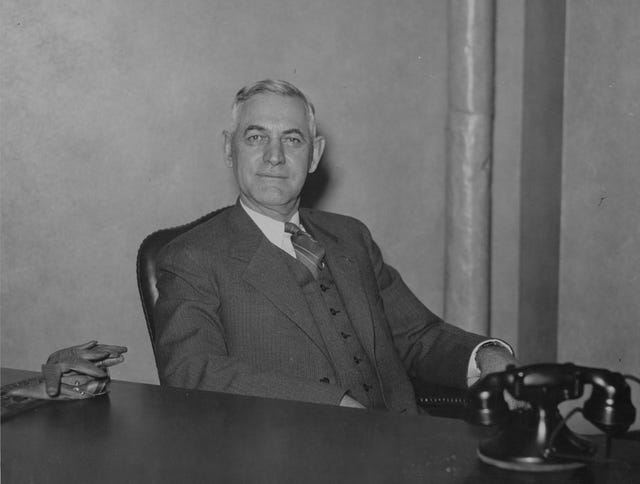

Although J. Edgar Hoover was never elected to any office, for decades, he was every bit as powerful as any person in the country. Hoover’s power emanated from his leadership of the FBI but was enhanced by his ready use of blackmail and, ironically, other criminal practices to stay in power. Since his death in 1972, Hoover’s legacy remains in conflict. Hoover’s critics say he harassed civil rights leaders, discriminated against gays (particularly federal workers) and gathered incriminating evidence to blackmail political figures; friend and foe. While his supporters point to Hoover’s modernization of law enforcement methods, his standardization of the the FBI’s fingerprint database and for bringing forensic science into criminal investigations as his legacy.

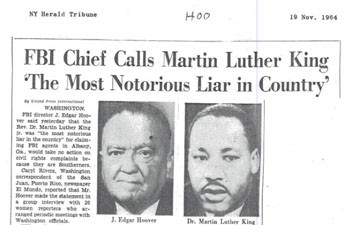

During a three week period 55 years ago, the dichotomy of the Hoover-King affair was defined. On Nov. 18, 1964, Hoover told a gathering of women reporters, “In my opinion, Dr. Martin Luther King is the most notorious liar in the country.” Hoover’s statement was in response to Dr. King’s suggestion that the F.B.I. was not doing enough to protect Freedom Riders fighting Jim Crow racism in the South. That “Freedom Summer” campaign to get African Americans to register to vote was marred by violence, including the killings of three civil rights workers in Mississippi.

Hoover’s comments prompted a request by Dr. King for a meeting with the Director. “I was appalled and surprised at your reported statement maligning my integrity,” King wrote in a telegram to Hoover. “What motivated such an irresponsible accusation is a mystery to me.” King turned the tables on the Director by telling reporters: “I cannot conceive of Mr. Hoover making a statement like this without being under extreme pressure….I have nothing but sympathy for this man who has served his country so well.” In contrast, privately Hoover called King “the burrhead” and “a tom cat with degenerate sexual urges.”

But before that meeting could be arranged, FBI assistant director and head of the Domestic Intelligence Division at the time, William C. Sullivan, sent an anonymous letter to King, threatening to make public the civil rights leader’s sex life. Hence known colloquially as the “suicide letter” for its suggestion that King kill himself to avoid the embarrassing revelations, it is unknown whether the letter was sent at Hoover’s direction. However, a full and uncensored copy can be found in Hoover’s confidential files at the National Archives. The letter dictated: “There is only one way out for you. You better take it before your filthy, abnormal, fraudulent self is bared to the nation”.

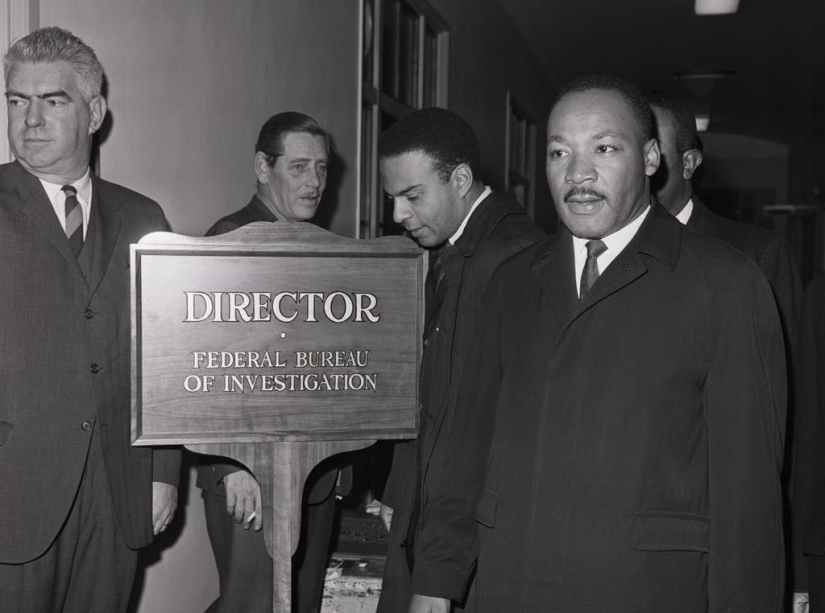

On Dec. 1st, Dr. King meets with J. Edgar Hoover to discuss the perceived slander campaign by the Director. Hoover later told Time magazine, “I held him in complete contempt…First I felt I shouldn’t see him, but then I thought he might become a martyr if I didn’t.” Hoover hated King for several reasons, first, because he believed King was a Communist, but also for King’s criticism of the FBI for failing to solve civil rights-related crimes. And, as Wm. Sullivan wrote in his memoir, “Hoover was opposed to change, to the civil rights movement, and to blacks.”

In 1963 Hoover used the King Communist accusation to convince Attorney General Robert Kennedy to allow the FBI tap King’s phones and bug his hotel rooms. Although Kennedy only gave written approval for “limited wiretapping” of Dr. King’s phones “on a trial basis, for a month or so”, Hoover extended the clearance so his men were “unshackled” to look for evidence in any areas of King’s life they deemed worthy. The bugs revealed that King was having extramarital affairs, which disgusted Hoover, a lifelong bachelor whose own sexuality remains a mystery. The bug also picked up King describing Hoover as, “old and senile.” Hoover shared his tapes of King’s sexual romps with President Lyndon Johnson, who then allegedly played them for his aides. Hoover also directed his assistants to leak the details of King’s sex life to reporters. A tape was also sent anonymously to King’s wife Coretta.

Around Thanksgiving, Newsweek reported that President Johnson had decided to “find a new chief of the FBI.” FBI agent Sullivan wrote that it was “Johnson who ordered Hoover to meet with King and patch things up.” Hoover ordered his aide Cartha DeLoach, “Make sure the meeting is in my office. And no press. Do you hear me, no press!” While DeLoach followed orders no-one informed Dr. King’s aides, and when the civil rights leader arrived at Hoover’s office, there was a mob of reporters waiting outside.

The 69-year-old Hoover met with the 35-year-old Dr. King and his aides, Ralph Abernathy and Andrew Young. “I’m grateful for the opportunity to meet with you,” King said. He told Hoover that he appreciated the work the FBI had done in civil rights cases and said that while “Many Negroes have complained that the FBI has been ineffective but I, myself discount such criticism. And I want to assure you that I have been seriously misquoted in the matter of slurs against the FBI.” Dr. King’s statement took about two minutes. After which, Hoover spoke without stopping for the better part of an hour extolling the virtues of the FBI and denouncing the communists. Meanwhile, America’s greatest Civil Rights orator sat quietly and listened.

During the meeting, Hoover was asked why the FBI didn’t have more black agents. “The problem is, we require not only a college diploma, but in most cases an advanced degree,” Hoover said. “We won’t water down our qualifications because of the color of a person’s skin.” The meeting ended without addressing the issues that had prompted the meeting. “We never got around to discussing the ‘most notorious liar’ business. Nor did we even get to mention the FBI surveillance,” Andrew Young later wrote in his memoir. “In fact, nothing happened except that Hoover rambled on and on about the virtues of the FBI.”

In 1970, two years after King’s assassination, Hoover told a Time reporter. “King was very suave and smooth. He sat right there where you’re sitting and said he never criticized the FBI. I said, ‘Mr. King’-I never called him reverend- ‘stop right there. You’re lying….If you ever say anything that’s a lie again, I’ll brand you a liar again.’ Strange to say, he never attacked the Bureau again for as long as he lived.” Nobody else present that day remembered that confrontation-not Young, not Abernathy, not even Deputy Director Deke DeLoach, who was taking notes that afternoon.

In 1970, two years after King’s assassination, Hoover told a Time reporter. “King was very suave and smooth. He sat right there where you’re sitting and said he never criticized the FBI. I said, ‘Mr. King’-I never called him reverend- ‘stop right there. You’re lying….If you ever say anything that’s a lie again, I’ll brand you a liar again.’ Strange to say, he never attacked the Bureau again for as long as he lived.” Nobody else present that day remembered that confrontation-not Young, not Abernathy, not even Deputy Director Deke DeLoach, who was taking notes that afternoon.

In the years after that meeting, Hoover tasked several FBI agents to 24-hour monitoring of the activities of Dr. King. The FBI Director directed his agents to set up wiretaps, monitor travel, conduct surveillance, and record all of King’s activities- including those he met with, what they discussed, how long they stayed, and how often they interacted- in an attempt to discredit or charge him with something.

President Truman once said, “We want no Gestapo or secret police. The FBI is tending in that direction.” J. Edgar Hoover used his power to further his own agenda and secure his position as leader of the most powerful law enforcement agency in the country. And black people were a favorite target of Hoover’s FBI. Legal scholar Randall Kennedy said that Hoover “viewed protest against white domination as tending toward treason.” This view of the world led Hoover to align himself with all of the forces of racial oppression, but he may have done his greatest damage not through action, but through inaction. He relentlessly pursued high profile targets like the Black Panthers, but neglected to protect the basic human rights of “ordinary” black citizens.

Because Hoover hated communists as much as he hated black people, he often equated one with the other, claiming that the civil rights movement was a tool of the communist party. Make no mistake about it though, J. Edgar Hoover’s enemies list did not end with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.. The great crime fighting G-man’s other targets included Ralph Abernathy, Muhammad Ali, James Baldwin, H. Rap Brown, Stokely Carmichael, Eldridge Cleaver, Tom Hayden, Ernest Hemingway, Abbie Hoffman, Malcolm X, and Huey P. Newton and wiretappings and illegal break-ins of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference that King headed.

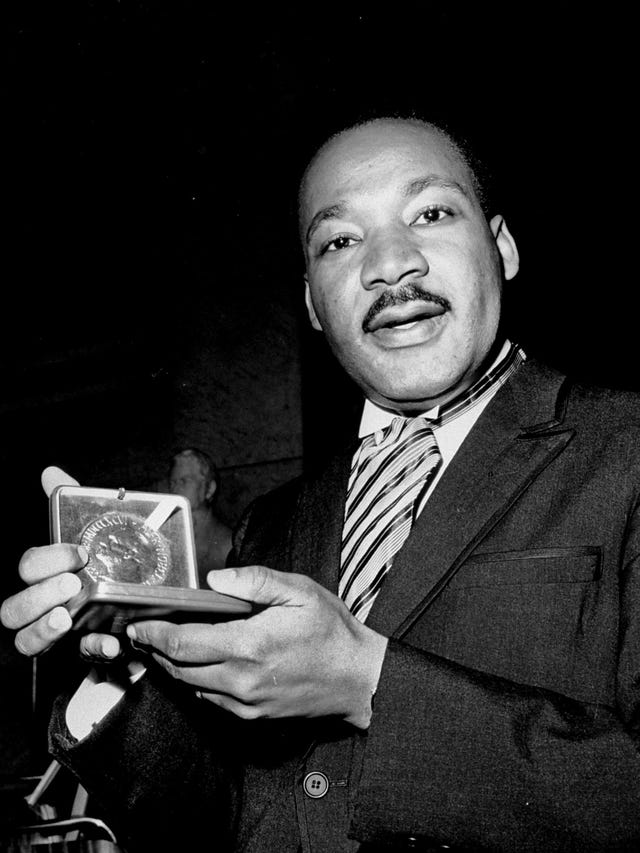

While the Hoover-King meeting was deemed unremarkable and went mostly unnoticed by the American press, it was viewed otherwise by the citizens of the world at large. On Dec. 10th, 1964 the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Dr Martin Luther King Jr., making him the youngest winner of the prestigious award. Officially, it was awarded to him for leading nonviolent resistance to racial prejudice in the U.S. At Dr. King’s acceptance speech in Oslo, he remarked, “I accept the Nobel Prize for Peace at a moment when 22 million Negroes of the United States of America are engaged in a creative battle to end the long night of racial injustice…I accept this award today with an abiding faith in America and an audacious faith in the future of mankind. I refuse to accept despair as the final response to the ambiguities of history…I believe that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word in reality…I believe that wounded justice, lying prostrate on the blood-flowing streets of our nations, can be lifted from this dust of shame to reign supreme among the children of men…I still believe that We Shall overcome!”

After King accepted the Nobel Peace Prize, Hoover wrote his reaction on a news clipping: “King could well qualify for the ‘top alley cat’ prize.” And even by 1969, a year after Dr. King’s death, FBI efforts to discredit the Civil Rights leader had not slackened. The Bureau furnished ammunition to opponents that enabled attacks on King’s memory, and tried to block efforts to honor the slain leader. The campaign to tarnish Dr. King’s legacy persisted until Hoover’s death in 1972.

Hoover’s meeting with Dr. King 55 years ago did nothing to enhance his personal legacy. Today, he is remembered as a cross-dressing closet homosexual suffering from paranoid delusions. But could self-loathing also qualify as a symptom of Hoover’s obsession of Dr. King, the Civil Rights movement and personal persecution of the black race?

In his 1993 book “Official and Confidential” author Anthony Summers said that ,in some black communities in the East, he discovered that it was generally believed J. Edgar Hoover had black roots and was even referred to as a “soul brother” in some circles. Writer Gore Vidal, a contemporary of the Director who grew up in Washington, D.C. in the 1930s also said in an interview: “It was always said in my family and around the city that Hoover was mulatto. And that he came from a family that passed.”

So, as you contemplate the many layers of political intrigue addressed in this article and populating the headlines, airwaves and social media today, keep in mind that things may not always appear as they seem. As the Wizard of Oz himself, Frank Morgan said way back in 1939. “Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain!” Oftentimes it is the legacy that reveals the real truths of an age or era. And that legacy can only be accurately deciphered through the lens of time.

Although Lincoln was the first to officially recognize the U.S. holiday of Thanksgiving, Halloween was just beginning to take root during the Civil War. Some historians credit the Irish for “inventing” Halloween in the United States. Or more specifically, the Irish “little people” with a tendency toward vandalism, and their tradition of “Mischief Night” that spread quickly through rural areas. According to American Heritage magazine (October 2001 / Vol. 52, Issue 7), “On October 31, young men roamed the countryside looking for fun, and on November 1, farmers would arise to find wagons on barn roofs, front gates hanging from trees, and cows in neighbors’ pastures. Any prank having to do with an outhouse was especially hilarious, and some students of Halloween maintain that the spirit went out of the holiday when plumbing moved indoors.”

Although Lincoln was the first to officially recognize the U.S. holiday of Thanksgiving, Halloween was just beginning to take root during the Civil War. Some historians credit the Irish for “inventing” Halloween in the United States. Or more specifically, the Irish “little people” with a tendency toward vandalism, and their tradition of “Mischief Night” that spread quickly through rural areas. According to American Heritage magazine (October 2001 / Vol. 52, Issue 7), “On October 31, young men roamed the countryside looking for fun, and on November 1, farmers would arise to find wagons on barn roofs, front gates hanging from trees, and cows in neighbors’ pastures. Any prank having to do with an outhouse was especially hilarious, and some students of Halloween maintain that the spirit went out of the holiday when plumbing moved indoors.” So it is that the origins of our two most celebrated autumnal holidays trace their American roots directly to our sixteenth President. And no President in American history is more closely associated with ghosts than Abraham Lincoln. However, where did all of these Lincoln ghost stories originate? After all, they had to start somewhere because one thing is for certain, they didn’t come from Abraham Lincoln. Many historians believe that most of those stories (at least the Lincoln ghost stories in the White House) came from a middle-aged freedman born in Anne Arundel County Maryland who worked as a White House “footman” serving nine Presidents from U.S. Grant to Teddy Roosevelt. His duties as footman included service as butler, cook, doorman, light cleaning and maintenance.

So it is that the origins of our two most celebrated autumnal holidays trace their American roots directly to our sixteenth President. And no President in American history is more closely associated with ghosts than Abraham Lincoln. However, where did all of these Lincoln ghost stories originate? After all, they had to start somewhere because one thing is for certain, they didn’t come from Abraham Lincoln. Many historians believe that most of those stories (at least the Lincoln ghost stories in the White House) came from a middle-aged freedman born in Anne Arundel County Maryland who worked as a White House “footman” serving nine Presidents from U.S. Grant to Teddy Roosevelt. His duties as footman included service as butler, cook, doorman, light cleaning and maintenance.

Jeremiah would often spin yarns for visiting reporters. Most of these tall tales were pure Americana always designed to bolster the reputation of his employer and their families, but some of Jerry’s best remembered tales were spooky ghost stories. Smith claimed that he saw the ghosts of Presidents Lincoln, Grant, and McKinley, and that they tried to speak to him but only produced a buzzing sound.

Jeremiah would often spin yarns for visiting reporters. Most of these tall tales were pure Americana always designed to bolster the reputation of his employer and their families, but some of Jerry’s best remembered tales were spooky ghost stories. Smith claimed that he saw the ghosts of Presidents Lincoln, Grant, and McKinley, and that they tried to speak to him but only produced a buzzing sound.

One Chicago reporter said this about Smith: “He is a firm believer in ghosts and their appurtenances, and he has a fund of stories about these uncanny things that afford immense entertainment for those around him. But there is one idea that has grown into Jerry’s brain and is now part of it, resisting the effects or ridicule, laughter, argument, or explanation. He firmly believes that the White House is haunted by the spirits of all the departed Presidents, and, furthermore, that his Satanic majesty, the devil, has his abode in the attic. He cannot be persuaded out of the notion, and at intervals he strengthens his position by telling about some new strange noise he has heard or some additional evidence he has secured.”

One Chicago reporter said this about Smith: “He is a firm believer in ghosts and their appurtenances, and he has a fund of stories about these uncanny things that afford immense entertainment for those around him. But there is one idea that has grown into Jerry’s brain and is now part of it, resisting the effects or ridicule, laughter, argument, or explanation. He firmly believes that the White House is haunted by the spirits of all the departed Presidents, and, furthermore, that his Satanic majesty, the devil, has his abode in the attic. He cannot be persuaded out of the notion, and at intervals he strengthens his position by telling about some new strange noise he has heard or some additional evidence he has secured.”

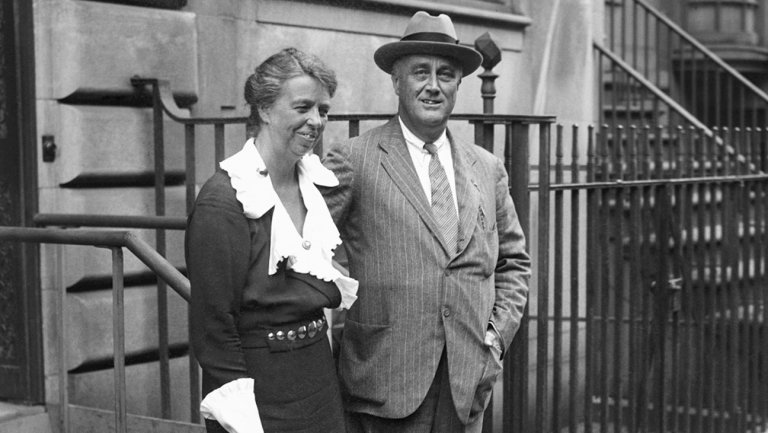

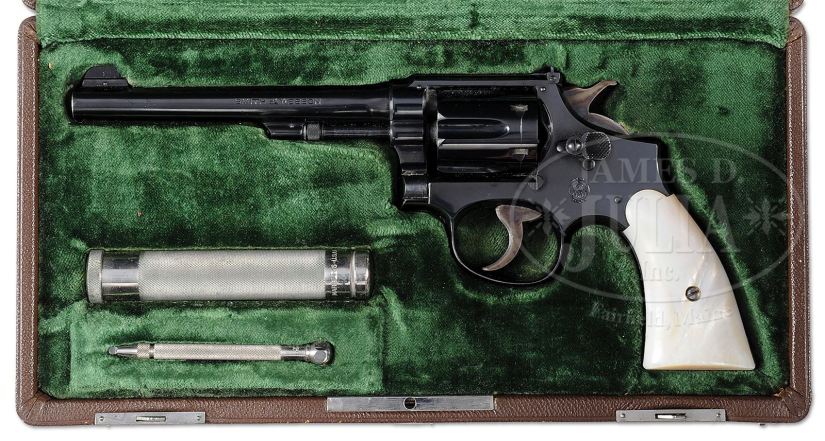

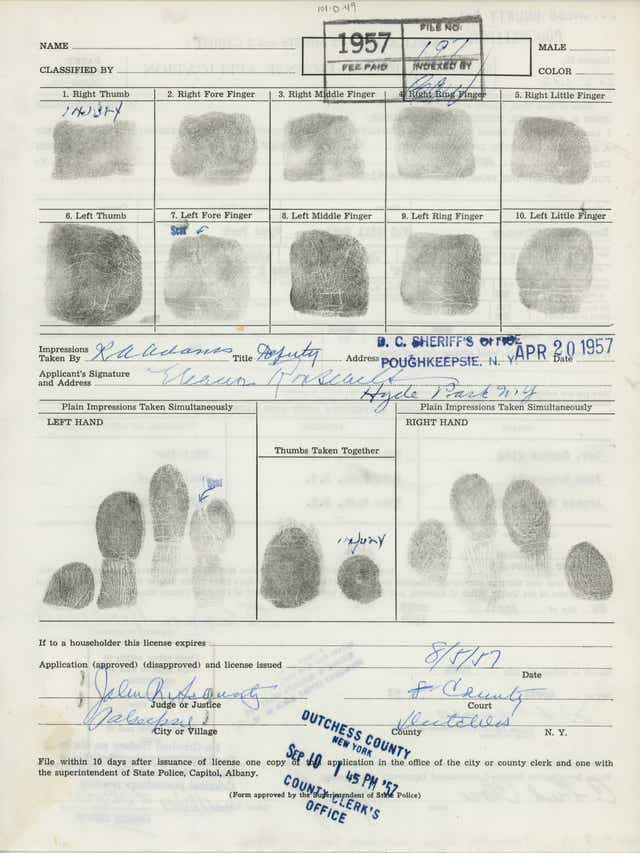

Oh, and by the way, Eleanor Roosevelt, the First lady of the world, icon of liberalism, fighter for civil rights, champion of the poor and marginalized and powerful advocate for women’s rights was a gun owner. Yes, Eleanor Roosevelt, mother of six, grandmother to twenty, was packing heat. Her application for a pistol permit in New York’s Dutchess County can be found at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in Hyde Park. With debate raging around the nation about gun control and Second Amendment rights, the fact that one of the icons of the Democratic womanhood not only owned a gun, but carried it for protection, may come as a surprise.

Oh, and by the way, Eleanor Roosevelt, the First lady of the world, icon of liberalism, fighter for civil rights, champion of the poor and marginalized and powerful advocate for women’s rights was a gun owner. Yes, Eleanor Roosevelt, mother of six, grandmother to twenty, was packing heat. Her application for a pistol permit in New York’s Dutchess County can be found at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in Hyde Park. With debate raging around the nation about gun control and Second Amendment rights, the fact that one of the icons of the Democratic womanhood not only owned a gun, but carried it for protection, may come as a surprise.

The application was processed by the Dutchess County Sheriff’s Office and signed by then-Sheriff C. Fred Close. It included a photo of Eleanor Roosevelt wearing a hat, fur stole and double strand of pearls. The reason for the pistol, according to Eleanor Roosevelt’s application, was “protection.” The timing of the pistol permit coincided with Eleanor Roosevelt’s travels throughout the South-by herself-in advocacy of civil rights. Those trips prompted death threats.

The application was processed by the Dutchess County Sheriff’s Office and signed by then-Sheriff C. Fred Close. It included a photo of Eleanor Roosevelt wearing a hat, fur stole and double strand of pearls. The reason for the pistol, according to Eleanor Roosevelt’s application, was “protection.” The timing of the pistol permit coincided with Eleanor Roosevelt’s travels throughout the South-by herself-in advocacy of civil rights. Those trips prompted death threats. Viewed from the perspective of 21st century politics, where Republicans and Democrats have lined up on opposing sides of the gun control debate, Eleanor Roosevelt’s pistol offers a fresh take on the ongoing debate over the rights of gun owners, the Democrats who want to curtail them and the Republicans who want to expand them.

Viewed from the perspective of 21st century politics, where Republicans and Democrats have lined up on opposing sides of the gun control debate, Eleanor Roosevelt’s pistol offers a fresh take on the ongoing debate over the rights of gun owners, the Democrats who want to curtail them and the Republicans who want to expand them.

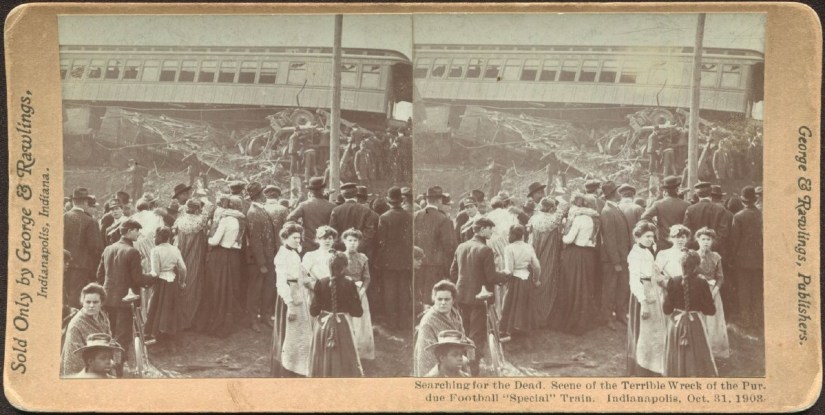

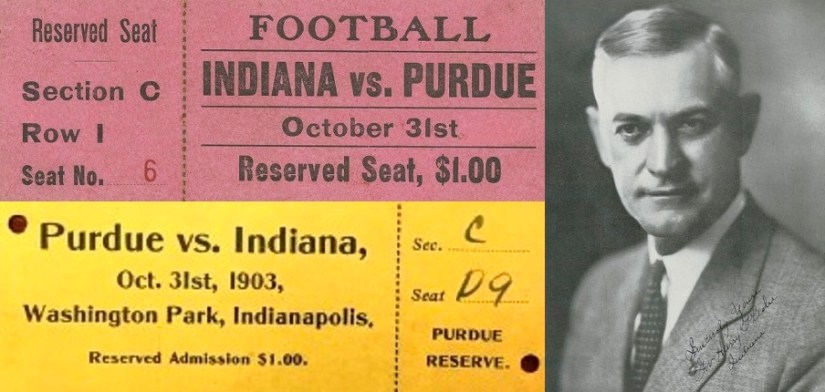

A total of 17 people died immediately, including 13 players, a coach, a trainer, a student manager and a booster. One member of the team miraculously landed on his feet and was unharmed after being thrown out a window. All the casualties were limited to the team’s railcar. Twenty-nine more players were hospitalized, several of whom suffered crippling injuries that would last the rest of their lives. Further tragedy was averted when several people, led by the “John Purdue Special” brakeman, ran up the track to slow down the second special train that was following 10 minutes behind the first. This heroic action undoubtedly saved many lives by preventing another train wreck. One of the survivors of the wreck was Purdue University President Winthrop E. Stone who remained on the scene to comfort the injured and dying.

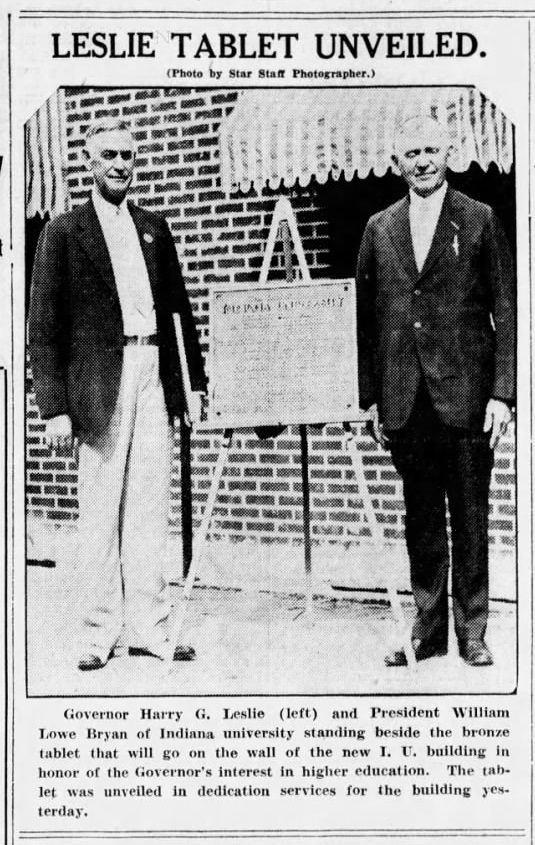

A total of 17 people died immediately, including 13 players, a coach, a trainer, a student manager and a booster. One member of the team miraculously landed on his feet and was unharmed after being thrown out a window. All the casualties were limited to the team’s railcar. Twenty-nine more players were hospitalized, several of whom suffered crippling injuries that would last the rest of their lives. Further tragedy was averted when several people, led by the “John Purdue Special” brakeman, ran up the track to slow down the second special train that was following 10 minutes behind the first. This heroic action undoubtedly saved many lives by preventing another train wreck. One of the survivors of the wreck was Purdue University President Winthrop E. Stone who remained on the scene to comfort the injured and dying. Walter Bailey, a reserve player from New Richmond, was grievously injured but refused aid so that others could be helped before him. Bailey would die a month later at the hospital from complications from his injuries and massive blood loss. Purdue team Captain Harry “Skeets” Leslie was found with ghastly wounds and covered up for dead. His body was transported to the morgue with the others. Leslie would later be upgraded to “alive” when, while his body lay on a cold slab at the morgue, someone noticed his right arm move slightly and he was found to have a faint pulse. Skeets was clinging to life for several weeks and needed several operations before he was out of the woods. Leslie would later go on to become the state of Indiana’s 33rd governor, the only Purdue graduate to ever hold that office. As a reminder of that Halloween train disaster, Skeets would walk with a limp for the rest of his life.

Walter Bailey, a reserve player from New Richmond, was grievously injured but refused aid so that others could be helped before him. Bailey would die a month later at the hospital from complications from his injuries and massive blood loss. Purdue team Captain Harry “Skeets” Leslie was found with ghastly wounds and covered up for dead. His body was transported to the morgue with the others. Leslie would later be upgraded to “alive” when, while his body lay on a cold slab at the morgue, someone noticed his right arm move slightly and he was found to have a faint pulse. Skeets was clinging to life for several weeks and needed several operations before he was out of the woods. Leslie would later go on to become the state of Indiana’s 33rd governor, the only Purdue graduate to ever hold that office. As a reminder of that Halloween train disaster, Skeets would walk with a limp for the rest of his life.

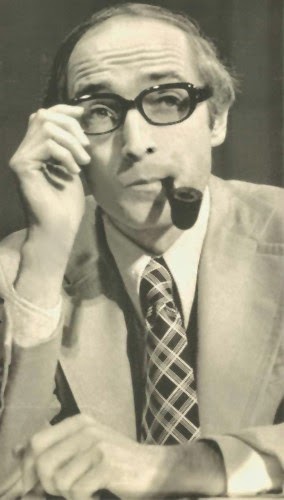

Tom Huston (derisively called “Secret Agent X-5” behind his back by some White House officials), the White House aide who devised the plan, was a young right-wing lawyer who had been hired as an assistant to White House speech writer Patrick Buchanan. Huston graduated from Indiana University in 1966 and from 1967 to 1969, served as an officer in the United States Army assigned to the Defense Intelligence Agency and was associate counsel to the president of the United States from 1969-1971.His only qualifications for his White House position were political – he had been president of the Young Americans for Freedom, a conservative campus organization nationwide.

Tom Huston (derisively called “Secret Agent X-5” behind his back by some White House officials), the White House aide who devised the plan, was a young right-wing lawyer who had been hired as an assistant to White House speech writer Patrick Buchanan. Huston graduated from Indiana University in 1966 and from 1967 to 1969, served as an officer in the United States Army assigned to the Defense Intelligence Agency and was associate counsel to the president of the United States from 1969-1971.His only qualifications for his White House position were political – he had been president of the Young Americans for Freedom, a conservative campus organization nationwide. Despite Huston’s warning that his namesake plan was illegal, Nixon approves the plan, but rejects one element-that he personally authorize any break-ins. Per Huston plan guidelines, the Internal Revenue Service began to harass left-wing think tanks and charitable organizations such as the Brookings Institution and the Ford Foundation. Huston writes that “making sensitive political inquiries at the IRS is about as safe a procedure as trusting a whore,” since the administration has no “reliable political friends at IRS.” He adds, “We won’t be in control of the government and in a position of effective leverage until such time as we have complete and total control of the top three slots of the IRS.” Huston suggests breaking into the Brookings Institute to find “the classified material which they have stashed over there,” adding: “There are a number of ways we could handle this. There are risks in all of them, of course; but there are also risks in allowing a government-in-exile to grow increasingly arrogant and powerful as each day goes by.”

Despite Huston’s warning that his namesake plan was illegal, Nixon approves the plan, but rejects one element-that he personally authorize any break-ins. Per Huston plan guidelines, the Internal Revenue Service began to harass left-wing think tanks and charitable organizations such as the Brookings Institution and the Ford Foundation. Huston writes that “making sensitive political inquiries at the IRS is about as safe a procedure as trusting a whore,” since the administration has no “reliable political friends at IRS.” He adds, “We won’t be in control of the government and in a position of effective leverage until such time as we have complete and total control of the top three slots of the IRS.” Huston suggests breaking into the Brookings Institute to find “the classified material which they have stashed over there,” adding: “There are a number of ways we could handle this. There are risks in all of them, of course; but there are also risks in allowing a government-in-exile to grow increasingly arrogant and powerful as each day goes by.”

During the question-and-answer session at that meeting, a woman stood up to relay a story of how her son was being beat up by neighborhood bullies, and how, after trying in vain to get law enforcement authorities to step in, gave her son a baseball bat and told him to defend himself. Meanwhile, the partisan crowd is chanting and cheering in sympathy with the increasingly agitated mother, and the chant: “Hooray for Watergate! Hooray for Watergate!” began to fill the room. Huston waited for the cheering to die down and says, “I’d like to say that this really goes to the heart of the problem. Back in 1970, one thing that bothered me the most was that it seemed as though the only way to solve the problem was to hand out baseball bats. In fact, it was already beginning to happen. Something had to be done. And out of it came the Plumbers and then a progression to Watergate. Well, I think that it’s the best thing that ever happened to this country that it got stopped when it did. We faced up to it…. [We] made mistakes.”

During the question-and-answer session at that meeting, a woman stood up to relay a story of how her son was being beat up by neighborhood bullies, and how, after trying in vain to get law enforcement authorities to step in, gave her son a baseball bat and told him to defend himself. Meanwhile, the partisan crowd is chanting and cheering in sympathy with the increasingly agitated mother, and the chant: “Hooray for Watergate! Hooray for Watergate!” began to fill the room. Huston waited for the cheering to die down and says, “I’d like to say that this really goes to the heart of the problem. Back in 1970, one thing that bothered me the most was that it seemed as though the only way to solve the problem was to hand out baseball bats. In fact, it was already beginning to happen. Something had to be done. And out of it came the Plumbers and then a progression to Watergate. Well, I think that it’s the best thing that ever happened to this country that it got stopped when it did. We faced up to it…. [We] made mistakes.”