Original publish date July 3, 2024. https://weeklyview.net/2024/07/03/the-liberty-bell-in-indianapolis/

The Liberty Bell is believed to have been brought to Pennsylvania by William Penn, arriving in Philadelphia on September 1, 1752. Its original use was to announce the opening of the Courts of Justice to the people and to call members of the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly together. Surprisingly, the main purpose of the Liberty Bell was to announce the accession of a member of the British royal family to the throne, and the proclamation of treaties of peace and declarations of war. Ironically, the bell rang out loudly when the Declaration of Independence was publicly read for the first time in Philadelphia, on July 8, 1776. Contrary to legend, the bell did not crack at that time. It cracked exactly fifty-nine years to the day later during ceremonies honoring the death of John Marshall, Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court who died two days prior on July 6, 1835.

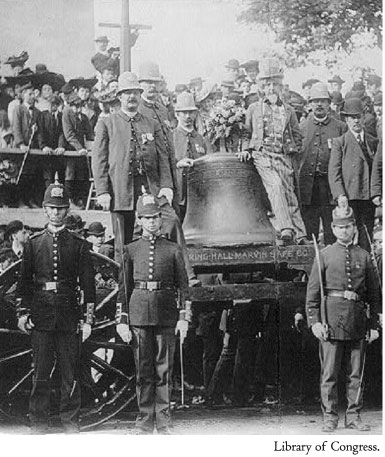

Since the time of American Independence, no other inanimate symbol has come to represent the United States more than The Liberty Bell. Although inextricably associated with the city of Philadelphia, The Liberty Bell has traveled through Indianapolis on three separate occasions. The first visit came to our city on Friday, April 28, 1893, on its way to the World’s Fair in Chicago. It was traveling over the Pennsylvania rail lines which sent it directly through the heart of Irvington. America’s most famous relic to freedom arrived at 5 a.m. and was placed on a sidetrack at Tennessee Street (present-day Capitol Avenue) at downtown Union Station. By the time Mayor Thomas Sullivan and Chief of Police Thomas Colbert arrived with a squad of eight guards, the street was already choked full of people anxious to see The Liberty Bell. Nervous carpenters worked feverishly building wooden ramps to access the bed of the converted passenger coach upon which the flag-draped relic was fastened.

The Indianapolis News reported, “Patriots came with such a rush to see the ‘Voice of Freedom’ that the ropes stretched around the car and along the street were incapable of holding the throng in check. Captain Charles Dawson began shouting at the top of his voice: ‘Get your tickets ready. Be sure and buy your tickets before you get in line!’ Of course, no tickets were necessary, but the cry had the desired effect. Hundreds fell out of the jam to make inquiries regarding tickets, and the police were then able to get the line properly formed.” The article details a strange phenomenon that swept that crowd. “When the crush was at its worst, a man passed up his matchbox to one of the policemen and asked that he touch the bell with the box. He felt that the mere touching of the bell would hallow the matchbox. Instantly, the policemen on guard were besieged with requests that they touch the bell with rings, ribbons, watches, canes, handkerchiefs, and a hundred other things.” Mothers and fathers handed babies up to the policemen for a rub against the bell. One child fainted amid the confusion. It resulted in a panic or sorts and “the touching incident had to be closed by the police for the sake of safety.”

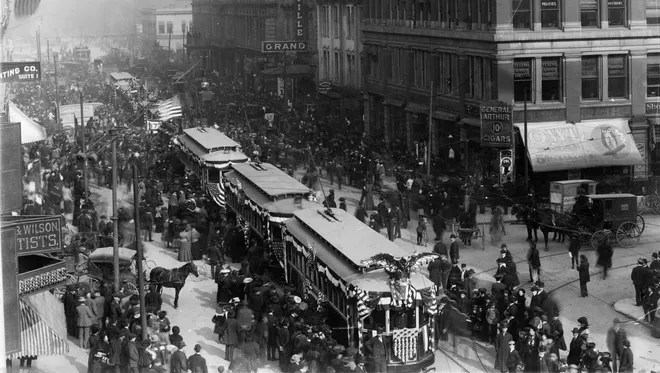

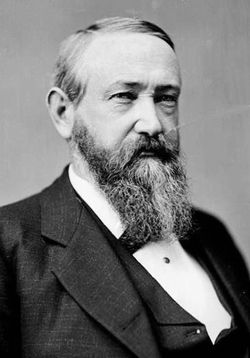

That 1893 visit culminated with a viewing at the Indiana State House where former President Benjamin Harrison delivered a speech honoring the bell. During the celebration, children from the Indianapolis Blind School were permitted to “get the sense of sight through the joy of touch. They fingered the beloved relic and went back to school fully satisfied.” The second visit of the Liberty Bell came on November 17, 1904, on its way back to Philly from the Louisiana Purchase Exposition aka the St. Louis World’s Fair. Sadly, the bell’s 6 p.m. arrival at the intersection of West and Washington Streets occurred the same day that the historic landmark Meridian Street Methodist Episcopal Church burnt to the ground nearby. The poet James Whitcomb Riley was among the official greeters for that 1904 visit. The Liberty Bell was on display at the interurban train sheds and Ohio Street traction station through the night, leaving the next morning. The culmination was a parade of all Indianapolis Public School children to the interurban station where they marched in front of the cherished relic to music provided by the Indianapolis News Newsboys Band. The Indianapolis News reported that the scene “moved grownups to tears and brought a full realization of the patriotic value of The Liberty Bell.” The bell was removed to the train station and sent on its way back to Philadelphia “almost buried under chrysanthemums that had been provided by patriotic citizens. As the car passed westward on Washington Street, the school children strewed the track with flowers.”

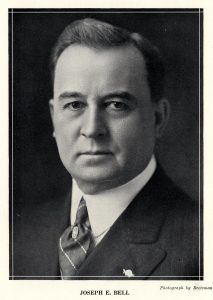

On July 5, 1915 (109 years ago this Friday) The Liberty Bell left Philadelphia for the last time on its way to the Panama-Pacific International Exposition World’s Fair in San Francisco, California. The bell debuted in the city by the bay on “Liberty Bell Day” on July 17. It was displayed in the Pennsylvania Building at the Fair for four months, every evening it was rolled and stored securely in a vault. Finally, on November 11, the bell left the Fairgrounds accompanied by cheers, church bells, and tearful smiles of farewell from those present. During the trip home, the bell made its final visit to Indianapolis. The event was planned (perhaps fittingly) by an Indianapolis Mayor named Joseph E. Bell, an interesting but long-forgotten figure in Indianapolis history. Bell, a Democrat and former law partner of John W. Kern, served from 1914 to 1918. Bell is notable for establishing the first police vice squad in the city and for his many public improvements including the the transformation of Pogue’s Run from an open sewer to an immense covered drain and a flood levee along the west bank of the White River and railroad track elevation permitting street and the development of the boulevard system. He also authorized the construction of the sunken gardens at Garfield Park. During Bell’s administration, 281 miles of streets, sidewalks, and sewers were built. Bell, a founder of the Indiana Democratic Club, died from an accidental, self-inflicted shotgun wound suffered at the Indianapolis Gun Club.

Just as in 1904, The Liberty Bell narrowly escaped disaster during that 1915 visit when a warehouse fire in Louisville swept two large warehouses, coming within a thousand feet of the relic. No wonder Philly hasn’t let the bell out of its sight since that trip. The Liberty Bell was greeted upon its 7:45 p.m. arrival in the Circle City by 5,000 flag-waving citizens lining East Washington Street. The relic bell visited over 400 cities during its trip home. The Liberty Bell welcoming parade was led by a contingent of GAR Civil War Veterans, mounted Policemen, and cars containing Teddy Roosevelt’s former Vice-President Charles W. Fairbanks, Governor Sam Ralston, Butler President Thomas Carr Howe, & Poet James Whitcomb Riley. The Nov. 22, 1915, Indianapolis News reported, “Impressive features of the occasion marked the stopping of the bell at the statehouse and courthouse where school choruses from the Manual Training and Technical High Schools led by the teachers of those schools, sang ‘America’ and other patriotic songs.

An interesting side note occurred when Indianapolis Motor Speedway’s founding father Carl Fisher volunteered to repair the crack in the Liberty Bell. The Nov. 20, 1915, News reported, “Practical-minded Carl F. Fisher is going to propose that they leave the bell and its celebrated crack in Indianapolis so that by processes now in use at the Prest-O-Lite plant, near the motor speedway, the long silence of The Liberty Bell may be broken and its voice again proclaim the sweetness of American freedom.” Fisher, perhaps the greatest huckster the Hoosier state ever saw, told the News, “Philadelphia has been living off that crack long enough. We have had at our plant in the last two years bells that are older than the Liberty Bell. They were on old Spanish men-of-war and merchant vessels that represented ports older than Philadelphia itself. Unless Philadelphia wakes up and has some repair work done pretty soon they’ll have a total wreck of their famous relic. We can patch that crack up as easily as a shoemaker half-soles a shoe. Expansion and contraction are making the bell’s crack wider, and something must be done to heal that wound. If they will just let Indianapolis play surgeon for their beloved patient we will show them that we can do it.” The News further reported, “It was learned that the Philadelphia people have a pride in the crack and do not wish it mended.” The train carrying the Liberty Bell left Indianapolis at 12:30 a.m. en route to Columbus, Indiana. On Thanksgiving day in 1915, Philadelphians welcomed the Liberty back to Independence Hall at nightfall after its cross-country tour. Although the bell has been “tapped” many times for historic events after that 1915 homecoming, on September 25, 1920, it was rung for the last time in ceremonies in Independence Hall celebrating the ratification of the 19th Amendment giving women the right to vote.