Original publish date: November 1, 2018

Halloween is over and once again, it is time to box up the decorations and compost the jack-o’-lanterns to get ready for the next holiday season. This October I spent some time tracking an old muse from my childhood, George Pogue. Not only is Pogue Indy’s oldest cold case, he is also the Circle City’s oldest ghost story. Over the past few weeks I have re-shared past stories on Pogue’s run and the story of his disappearance. This week I’ll talk about his legacy.

The city of Indianapolis owes George Pogue a debt of gratitude. It was Pogue whom most historians credit as being our city’s first white settler. In 1819 Pogue followed a meandering narrow deerpath paralleling the banks of a pristine little stream that eventually fed into the West Fork of the White River. The Genesis of this once craggy little creek can be found near the intersection of Massachusetts and Ritter avenues on the east side. It spills into the White River south of the Kentucky Avenue bridge in the shadow of Lucas Oil Stadium.

Prior to Pogue’s arrival, native American Indians would often follow Pogue’s Run hunting the wildlife that naturally gathered there. 58-year-old George Pogue, a blacksmith from Connersville, blazed the trail present-day eastsiders know as Brookville Road. Depending on which historian you talk to, on or about March 2, 1819, Pogue built (or occupied) a cabin where Michigan Street currently crosses Pogue’s Run for his family of seven. After Pogue’s mysterious disappearance in April 1821, the creek he followed to arrive in the Whitewater basin became known as Pogue’s Run.

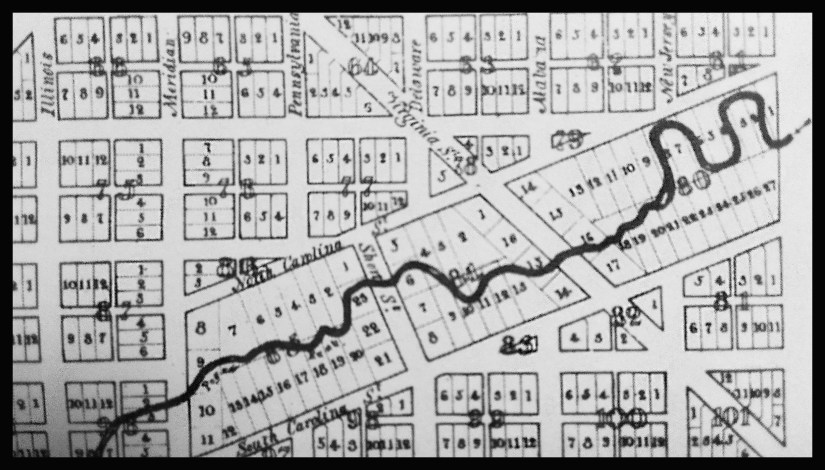

If you Google Alexander Ralston’s original plat map of the city of Indianapolis, you will see Pogue’s run traversing diagonally across the southeast portion of the “Mile Square” area like a giant black snake. Just as Pogue’s mysterious end did not fit the desired narrative put forth by Indianapolis’ founding fathers, Pogue’s run disturbed the orderliness of Ralston’s tidy grid pattern. Before the state government could be moved to Indianapolis from Corydon, fifty dollars was spent to rid swampy Pogue’s Run of the mosquitoes that made it a “source of pestilence”.

Seems that poor old Pogue’s run never had a chance. It was too small to be a canal and too big to be a latrine. So city planners decided that the troublesome trickling waterway needed to be “straight jacketed” once and for all. Pogue’s run was prone to flooding and it had a funky odor hanging over it that wrinkled the tapestry the city’s elite were trying to create. So, beginning in 1914, a year long, million-dollar project variously known as the “Pogue’s Run Drain” and the “Pogue’s Run Improvement” was undertaken to hide the historic waterway. City planners felt that the stream’s submersion beneath downtown Indianapolis (from New York Street on the east side to the White River on the west side) would make the perfect aqueduct to alleviate flooding in the Circle City.

Sounds like a reasonable, viable engineering solution made by concerned public servants to obviate a city eyesore while protecting the citizenry at the same time, right? Well, it may run a little bit deeper than that. A number of factors influenced the decision to “straitjacket” Pogue’s Run, including the economic and human costs from decades of violent flooding, public health risks from diseases, and the stream’s unsightly and unpleasant smell due to years of sewage and industrial pollution. The covering of Pogue’s Run paved the way for the expansion of railroad track elevations, which in turn alleviated congestion on Indianapolis’ busy streets and avenues. It also enabled the city to create Brookside Park in 1898 at the spot where Pogue’s run enters downtown Indianapolis.

Although the legendary waterway now more closely resembles a drainage ditch, make no mistake about it, Pogue’s Run is real. It runs under the city of Indianapolis for nearly two-and-a-half miles, and it’s possible to walk from one end to another. Every underground tunnel presents an irresistible mystery, but Pogue’s Run has a more ghostly history than most. The Pogue’s run tunnels are reportedly home to the spirit of old George Pogue who lords over the dozen or so unfortunate victims of the floods that plagued the city via the waterway for nearly a century before it was covered over.

As detailed in previous articles, one morning George Pogue walked out his front door in search of his lost dog and disappeared forever. He was also trailing a Native American man known as “Wyandotte John” whom he suspected of stealing horses from his farm. Pogue walked over hill and was never seen again. His body was never found. Even though Pogue vanished nearly 200 years ago, his name hits the headlines every few years. It seems that whenever a foundation for a business in downtown Indianapolis is dug and human remains are found, the ghost of George Pogue rises from his unknown grave.

The first widely used cemeteries in Indianapolis didn’t start popping up until long after George Pogue disappeared. While the “City Cemetery”, ironically located on Kentucky Avenue near the White River where George Pogue disappeared, can be traced back to 1821, it was not at all what we would consider a cemetery today. Greenlawn Cemetery was added around 1834 as an 8 acre addition. By 1852 this pioneer cemetery had reached 25 acres and was quickly running out of room. Crown Hill opened in 1864 and Greenlawn quickly fell out of favor. By the 1890s, Greenlawn was gone. In George Pogue’s time, people were often buried where they were found or nearby where they worshiped, worked or lived. Burial records are scarce, wooden markers disintegrate and landmarks disappear. So it is not uncommon for human remains to pop up from time to time even today. So, needless to say, George Pogue does not rest in peace.

When the city of Indianapolis buried their troublesome waterway in 1915, Pogue’s run, like its namesake, disappeared. The trickling little stream is now forever trapped underground. And so is the ghost of George Pogue. Legend claims that Pogue is doomed to walk this underworld purgatory until his remains are found and he is given a proper burial. Pogue leads a small army of ghosts whose souls were lost in the flooding that once plagued the area.

Today, no one thinks much about the creek that runs underneath downtown Indianapolis. True, Hoosiers cling tightly to the White River by naming parks, streets and events in its honor. But unlike other major American cities, the Circle City has very few myths or legends surrounding its chief waterways. That is unless you count the tales of late-night TV host David Letterman and his friends attempting to traverse the central canal via canoe back in the “naptown” days. As a homegrown Hoosier, it has always been a mystery to me why the Pogue’s run waterway has not been more prominently featured in our city’s weird history.

During George Pogue’s era, antebellum times and the years after the Civil War and Reconstruction, flooding was not really a concern in Indianapolis. The Circle City really had no riverfront development to speak of, roads were sparse and unpaved and any excess winter water thaws had plenty of places to go. In past columns I have detailed a few of the many floods that plagued Indy in the years before the Pogue’s run tunnels were created. The Easter Sunday floods in 1913 brought twelve inches of rain in a five day period and the White River crested to 31.5 feet; 19.5 feet above flood stage. No one knows what the true crest was because the city’s measuring equipment and gauges washed away at 29.5 feet. 70,000 cubic feet per second, an amount 50 times greater than normal, sent torrents of water rushing through the city. In Indianapolis, 7000 families lost their homes and over 25 deaths were reported as a result of this flood. Statewide, 200,000 people lost their homes and over 200 lives were lost. More than a few of those bodies were never found and their spirits, like that of its namesake, haunt the Pogue’s run tunnels today.

A couple of Sundays ago I was joined by several Irvington Ghost tour volunteers in a search of the Pogue’s run tunnels. Rhonda and I were joined that day by our daughter Jasmine, friends Elise Remissong and Jada Cox, Kris and Roger Branch, Steve Hunt, Tim Poynter, Christy and Cameron McAbee, Trudy and Steve Rowe and Cindy Adkins. WISH-TV Channel 8 TV’s Joe Melillo also joined us for a pre-Halloween trek in search of the ghost of old George Pogue. The results of our trip can be found on the WISH TV website under Joe’s banner. Joe’s segment captured only a fraction of what took place down there.

That day, the Colts were playing the Buffalo Bills at Lucas oil above us. (the Colts won 37 to 5) Inside the century old pitch-black tunnel the water had slowed to a trickle. The entrance to the Pogue’s run tunnel is hidden in a thickly wooded area within sight of the downtown skyline. The city of Indianapolis maintains Pogue’s run very nicely and has recently constructed a two-story wooden walkway leading down to the tunnel entrance. Upon entering the mouth of the tunnel the original stream can be seen entering the concrete spillway looking much as it has for nearly two centuries.

The concrete walls leading into the tunnel are festooned with spray-painted graffiti indicative of its big city location. The water stream is contained down the center of the trough with dry foot paths on either side. About 100 yards down stream inside the tunnel, a separate parallel tunnel is revealed through large round vents in the walls that are easy to step through. The upper channel is the spillway used for relief of excess water flowing through Pogue’s run when necessary. These walls are also peppered with graffiti as expected. Mostly introspective, sometimes profane, the graffiti is often nonsensical; logical only to whomever placed it there.

There are rats down here along with spiders, snakes and the occasional stranded fish from floods past. There is also evidence that the homeless population of Indianapolis occasionally seek shelter in the tunnels, but most of that evidence gets washed away by the floodwaters on a regular basis. The temperature outside is just above freezing, but it is warm here in the tunnels. So warm that it is easy for our team of urban spelunker’s to feel overdressed. The water can be deep in places depending on the rainfall. The total blackness of the Pogue’s run tunnels cannot be understated. Without the aid of a trusty flashlight or lantern, it is impossible to see your hand held in front of your face.

The ceiling and sidewalls are cracked in places, betraying rushing floodwaters of years gone by. The side tunnels are made of brick and occasionally they branch off the main route to parts unknown. Cell phones are useless in the tunnel; there ain’t no service down here . There are manholes and open grates that I suppose could be accessed to determine one’s location, but thanks to Stephen King’s “It” (and Pennywise the sewer clown) I wouldn’t recommend it. In places, perhaps owing to the day’s Colts Sunday atmosphere, it is possible to hear activity on the streets above including music and conversation. But mostly it is quiet. Occasionally cars passing above make high-pitched traffic sounds that can be confused with the cries of a baby or wounded animal, but the logical mind soon determines the source. Once in a while one of these vehicles will pass directly over a manhole with a thunderous result that echoes through the tunnel and shakes even the most resolute of subterranean urban explorers.

Upon closer examination, evidence remains of those original pre-World War I era tunnels. Brick troughs and well foundations pepper the tunnels as do the rotted remains of wooden trusses and the occasional displaced iron train rail, the presence of which immediately elicits the thought “how did that get down here?” Oddly, there’s not much of an echo down here. The voice carries, but it doesn’t carry far. When the visitor cups the mouth and lets loose a “Hello”, it rolls only a few rods before disappearing into the darkness. But is there anything else down in the old Pogue’s Run tunnels?

As a student of history, I often find myself asking that question. Is there anything else? I rely on a few friends with deeper insight in that department to answer that query. Tim Poynter, founder of the SPIRIT Paranormal team, observed a few spirits lingering in the tunnels of Pogue’s run, “I encountered the spirit of a light-skinned black man dressed in mid 20th century clothing within a few hundred feet of the opening. His attitude seemed to be one of ‘stay back’which is not uncommon. I imagine this was the spirit of a homeless man who passed while living down there in the tunnels.” Intuitive Cindy Adkins echoed Tim’s feelings at the mouth of the tunnel, “I did not see the gentleman until we got into the tunnel. I was not getting a bad feeling at all just that we were invading his space and he did not like that too well.” Cindy would encounter this man further down in the tunnels of Pogue’s run.

WISH-TV Channel 8 TV reporter Joe Melillo segregated three of our number, Cindy Adkins, Christy McAbee and Steve Hunt, deep within the depths of the Pogue’s Run tunnel. Here, light and sound go to die. Joe watched as the trio “spoke” with the dead. Cindy Adkins is a gifted intuitive and the only person I have encountered who has had an actual conversation with a ghost on tape (or EVP). When Joe Melillo turned on his camera, this man’s spirit came out to play.

“The gentleman is over 6 feet tall,” says Cindy. “He told me there was a house fire and his big two-story home was completely engulfed in flames. He told me his family was killed in the fire. His house was near Pogue’s run and he lived down there in the tunnels. He likes it down in the tunnels and he doesn’t want to leave. But while we were down there and Joe was taping, a woman joined us. Her initials were C. L. and I kept getting the date 1964. She was lost down there in the tunnels and said that she died of a drug overdose. Christy, Steve and I managed to clear her spirit and send her on her way to the light. But the man is still down there. He just laughed when I asked him if he wanted to leave too.”

As I write this article, Joe Melillo’s segment has yet to air. His WISH-TV Channel 8 Pogue’s run segment airs on Halloween morning. When asked for his thoughts and impressions on the Pogue’s run adventure, Joe Melillo siad, “I would say the best way to describe the experience for me was stifling… Almost suffocating. Very dense down there and it made me have a headache. Overall I did feel something, but I am more of a history guy so the paranormal things don’t hit me as hard. When we sat with the group of paranormal investigators I was there to document the exercise, but nothing happened to me specifically. I was so ready for someone to touch me or to see a shadow figure, but I got nothing. At least this time. Maybe next time I’ll have better luck.” Yes, Joe, maybe next time. Sounds like the Pogue’s run entities will still be there, waiting for you.

Some historians argue that Pogue simply moved into an existing cabin that had been built and briefly occupied by Newton “Ute” Perkins. Others claim that John Wesley McCormick accompanied Pogue to Indianapolis from Connersville and deserves to be mentioned as the first settler in the Capitol city. But Perkins moved to Rushville “on account of loneliness” and McCormick settled near Bloomington where he later had a popular state park named in his honor. But for this historian, George Pogue is the man. Why? Because one day, George Pogue simply vanished from the face of the earth.

Some historians argue that Pogue simply moved into an existing cabin that had been built and briefly occupied by Newton “Ute” Perkins. Others claim that John Wesley McCormick accompanied Pogue to Indianapolis from Connersville and deserves to be mentioned as the first settler in the Capitol city. But Perkins moved to Rushville “on account of loneliness” and McCormick settled near Bloomington where he later had a popular state park named in his honor. But for this historian, George Pogue is the man. Why? Because one day, George Pogue simply vanished from the face of the earth. One evening at twilight, an Indian brave known as “Wyandotte John”, stopped at the Pogue family cabin asking for food and shelter for the night. Although wary of the request, some of Pogue’s horses had been recently stolen and he was determined to track down the thieves. The Indian had a bad reputation and the rumor was that he had been banished from his own tribe in Ohio for some unknown offense and was now wandering aimlessly among the various Indiana tribes in the area. Wyandotte John had spent the previous winter living rough, but comfortably, in a hollowed out sycamore log perched under a bluff just east of the area that, a decade later, would become the spot where the National Road bridge crossed the White River. On the inside of the log he had fashioned hooks by cutting forks from tree limbs, on which he rested his gun. At the open end of the log near the waterline he built his fire, which kept the wildlife away while heating the enclosure at the same time.

One evening at twilight, an Indian brave known as “Wyandotte John”, stopped at the Pogue family cabin asking for food and shelter for the night. Although wary of the request, some of Pogue’s horses had been recently stolen and he was determined to track down the thieves. The Indian had a bad reputation and the rumor was that he had been banished from his own tribe in Ohio for some unknown offense and was now wandering aimlessly among the various Indiana tribes in the area. Wyandotte John had spent the previous winter living rough, but comfortably, in a hollowed out sycamore log perched under a bluff just east of the area that, a decade later, would become the spot where the National Road bridge crossed the White River. On the inside of the log he had fashioned hooks by cutting forks from tree limbs, on which he rested his gun. At the open end of the log near the waterline he built his fire, which kept the wildlife away while heating the enclosure at the same time. When the Indian left the next morning, Pogue grabbed his gun and his dog and followed as Wyandotte John walked towards the river and the pioneer settlement. Pogue followed for some distance waiting for the Indian to turn towards the native camps, but the Indian kept walking towards the white settlers. The two men disappeared over a rise and George Pogue was never seen or heard from again. The settlers formed a company of armed men to search all the Indian camps within fifty miles of the settlement looking for some trace of Pogue, but his fate remains a mystery to this day. The conclusion is that he was killed by Indians. Locals claimed to have seen his horse and several of his possessions in the hands of local tribes. The dog was purportedly killed, cooked and eaten.

When the Indian left the next morning, Pogue grabbed his gun and his dog and followed as Wyandotte John walked towards the river and the pioneer settlement. Pogue followed for some distance waiting for the Indian to turn towards the native camps, but the Indian kept walking towards the white settlers. The two men disappeared over a rise and George Pogue was never seen or heard from again. The settlers formed a company of armed men to search all the Indian camps within fifty miles of the settlement looking for some trace of Pogue, but his fate remains a mystery to this day. The conclusion is that he was killed by Indians. Locals claimed to have seen his horse and several of his possessions in the hands of local tribes. The dog was purportedly killed, cooked and eaten. As every Circle City student knows, Indianapolis was laid out in 1815 by Alexander Ralston, an assistant to French architect Pierre L’Enfant, the man who designed Washington D.C. Ralston chose to design the city in a grid pattern, similar to the District of Columbia. There was just one problem; Pogue’s Run. The swampy little creek named after the ghost of an enigmatic city pioneer, called a “source of pestilence” because of all the mosquitoes it attracted, disturbed the orderliness of Ralston’s master plan and required him to make contingencies for it.

As every Circle City student knows, Indianapolis was laid out in 1815 by Alexander Ralston, an assistant to French architect Pierre L’Enfant, the man who designed Washington D.C. Ralston chose to design the city in a grid pattern, similar to the District of Columbia. There was just one problem; Pogue’s Run. The swampy little creek named after the ghost of an enigmatic city pioneer, called a “source of pestilence” because of all the mosquitoes it attracted, disturbed the orderliness of Ralston’s master plan and required him to make contingencies for it. Since much of Pogue’s Run downtown path was diverted underground via hidden tunnels, it is hard for us to imagine today what it must have looked like to the eyes of Indianapolis’ earliest residents. However, the atmosphere of the original waterway was perhaps best captured in an 1840 painting by Jacob Cox. Titled “Pogue’s Run, The Swimming Hole”, this tranquil and pastoral landscape depicts a pair of cows drinking from a stream under a bridge where Pogue’s Run crosses Meridian Street. The image presents a realistic portrayal of the location as it appeared before it became the site where Union Station (which was originally built on pylons over Pogue’s Run) rests today . Although relatively unknown by today’s Circle City denizens, Antebellum Pogue’s Run was the subject of many works of art and poetry by our forefathers.

Since much of Pogue’s Run downtown path was diverted underground via hidden tunnels, it is hard for us to imagine today what it must have looked like to the eyes of Indianapolis’ earliest residents. However, the atmosphere of the original waterway was perhaps best captured in an 1840 painting by Jacob Cox. Titled “Pogue’s Run, The Swimming Hole”, this tranquil and pastoral landscape depicts a pair of cows drinking from a stream under a bridge where Pogue’s Run crosses Meridian Street. The image presents a realistic portrayal of the location as it appeared before it became the site where Union Station (which was originally built on pylons over Pogue’s Run) rests today . Although relatively unknown by today’s Circle City denizens, Antebellum Pogue’s Run was the subject of many works of art and poetry by our forefathers. Today, as the waterway runs south it most closely resembles its original creek form as it winds through a housing development fronting Massachusetts Avenue and continues through Brookside Park. Skirting the south edge of the Cottage Home neighborhood, between 10th and New York Streets , it disappears into an underground aqueduct. It continues flowing under Banker’s Life Fieldhouse and Lucas Oil Stadium, and empties into the White River at 1900 S. West St. near Kentucky Avenue.

Today, as the waterway runs south it most closely resembles its original creek form as it winds through a housing development fronting Massachusetts Avenue and continues through Brookside Park. Skirting the south edge of the Cottage Home neighborhood, between 10th and New York Streets , it disappears into an underground aqueduct. It continues flowing under Banker’s Life Fieldhouse and Lucas Oil Stadium, and empties into the White River at 1900 S. West St. near Kentucky Avenue.

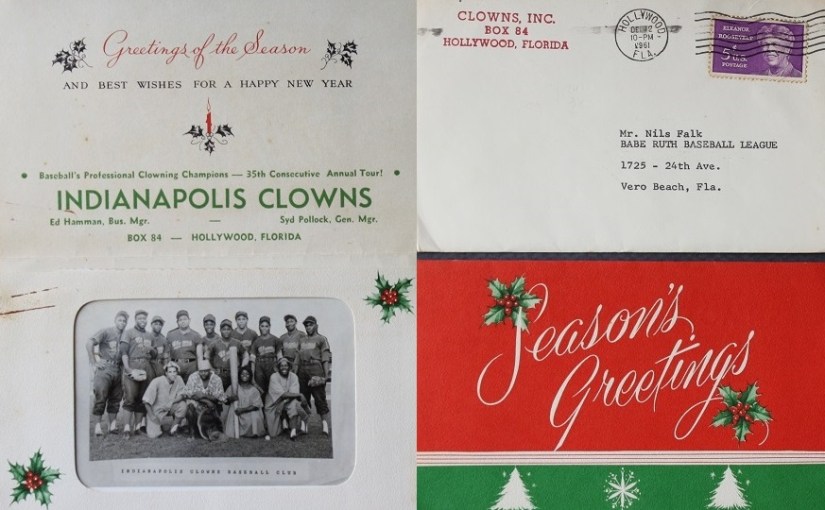

The card reads: “Greetings of the Season and Best Wishes for a Happy New Year. Baseball’s Professional Clowning Champions- 35th Consecutive Annual Tour! Indianapolis Clowns Ed Hamman, Bus. Mgr. Syd Pollack, Gen. Mgr. Box 84- Hollywood, Florida” inside. The original mailing envelope has the return address on front and same on back via an embossed stamp on the back. The Christmas card was sent to the Babe Ruth Baseball League in Vero Beach, Florida. True baseball fans will recognize Vero Beach as the spring training home of former Negro leader Jackie Robinson’s Brooklyn Dodgers and later the Koufax/Drysdale Los Angeles Dodgers. For a baseball fanatic, there is a lot going on in this little Christmas card.

The card reads: “Greetings of the Season and Best Wishes for a Happy New Year. Baseball’s Professional Clowning Champions- 35th Consecutive Annual Tour! Indianapolis Clowns Ed Hamman, Bus. Mgr. Syd Pollack, Gen. Mgr. Box 84- Hollywood, Florida” inside. The original mailing envelope has the return address on front and same on back via an embossed stamp on the back. The Christmas card was sent to the Babe Ruth Baseball League in Vero Beach, Florida. True baseball fans will recognize Vero Beach as the spring training home of former Negro leader Jackie Robinson’s Brooklyn Dodgers and later the Koufax/Drysdale Los Angeles Dodgers. For a baseball fanatic, there is a lot going on in this little Christmas card. The team photo pictures 10 players in old wool baseball uniforms standing in a line with another four players dressed in comic field costumes including a female player holding one of the Clowns’ trademark props, a grossly oversized baseball bat. The Clowns were one of the first professional baseball teams to hire a female player. They featured three prominent women players on their roster in the 1950s: Mamie “Peanut” Johnson (1935-2017) a right handed pitcher who went 33-8 in 3 seasons with the Clowns, Constance “Connie” Morgan (1935-1996) who played 2 seasons at second base for the Clowns and the first female player in the Negro Leagues, Marcenia “Toni” Stone (1921-1996) who once got a hit off of Satchel Paige.

The team photo pictures 10 players in old wool baseball uniforms standing in a line with another four players dressed in comic field costumes including a female player holding one of the Clowns’ trademark props, a grossly oversized baseball bat. The Clowns were one of the first professional baseball teams to hire a female player. They featured three prominent women players on their roster in the 1950s: Mamie “Peanut” Johnson (1935-2017) a right handed pitcher who went 33-8 in 3 seasons with the Clowns, Constance “Connie” Morgan (1935-1996) who played 2 seasons at second base for the Clowns and the first female player in the Negro Leagues, Marcenia “Toni” Stone (1921-1996) who once got a hit off of Satchel Paige. knew how to order off the menu. Aaron first experienced overt northern style racism while playing with the Clowns. The team was in Washington, D.C. and a few of the Clowns’ players decided to grab a pregame breakfast in a restaurant behind Griffith Stadium. The players were seated and served but after they finished their meals, they could hear the sounds of employees breaking all the plates in the kitchen. Aaron and his teammates were stung by the irony of being in the capital of the “Land of Freedom” whose employees felt they “had to destroy the plates that had touched the forks that had been in the mouths of black men. If dogs had eaten off those plates, they’d have washed them.”

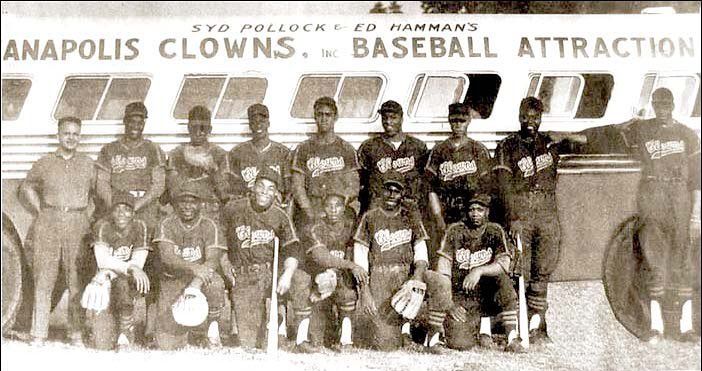

knew how to order off the menu. Aaron first experienced overt northern style racism while playing with the Clowns. The team was in Washington, D.C. and a few of the Clowns’ players decided to grab a pregame breakfast in a restaurant behind Griffith Stadium. The players were seated and served but after they finished their meals, they could hear the sounds of employees breaking all the plates in the kitchen. Aaron and his teammates were stung by the irony of being in the capital of the “Land of Freedom” whose employees felt they “had to destroy the plates that had touched the forks that had been in the mouths of black men. If dogs had eaten off those plates, they’d have washed them.” During Aaron’s tenure the Clowns were a powerhouse team in the Negro American League. However, the story of the Indianapolis Clowns does not begin, or end, with the Hank Aaron connection. The team traces their origins back to the 1930s. They began play as the independent Ethiopian Clowns, joined the Negro American League as the Cincinnati Clowns and, after a couple of years, relocated to Indianapolis. The team was formed in Miami, Florida, sometime around 1935-1936 and was originally known as the Miami Giants. After a couple years the team changed its name to the Miami Ethiopian Clowns and hit the road to become the longest running barnstorming team in professional baseball history.

During Aaron’s tenure the Clowns were a powerhouse team in the Negro American League. However, the story of the Indianapolis Clowns does not begin, or end, with the Hank Aaron connection. The team traces their origins back to the 1930s. They began play as the independent Ethiopian Clowns, joined the Negro American League as the Cincinnati Clowns and, after a couple of years, relocated to Indianapolis. The team was formed in Miami, Florida, sometime around 1935-1936 and was originally known as the Miami Giants. After a couple years the team changed its name to the Miami Ethiopian Clowns and hit the road to become the longest running barnstorming team in professional baseball history.

Harlem Globetrotter star “Goose” Tatum also played for the Clowns during this time. Goose was as much of a showman on the diamond as he was on the basketball court. Whether fielding balls with a glove triple the size of a normal one, confusing opposing players with hidden ball tricks or playing second base while seated in a rocking chair, Tatum was amazing. During the same era, Richard “King Tut” King played the field using an enormous first baseman’s mitt and occasionally augmenting his uniform with grass hula skirts in the field. King, who spent over 20-years with the Clowns, paved the way for great white baseball comedians like Max Patkin.

Harlem Globetrotter star “Goose” Tatum also played for the Clowns during this time. Goose was as much of a showman on the diamond as he was on the basketball court. Whether fielding balls with a glove triple the size of a normal one, confusing opposing players with hidden ball tricks or playing second base while seated in a rocking chair, Tatum was amazing. During the same era, Richard “King Tut” King played the field using an enormous first baseman’s mitt and occasionally augmenting his uniform with grass hula skirts in the field. King, who spent over 20-years with the Clowns, paved the way for great white baseball comedians like Max Patkin. By 1966 the Indianapolis Clowns were the last Negro league team still playing. The Clowns continued to play exhibition games into the 1980s, but as a humorous sideshow rather than a competitive sport. After many years on the road as a barnstorming team, the Clowns finally disbanded in 1989. The Clowns were also the first team to feature women as umpires. The 1976 movie “The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings”, starring James Earl Jones, Billy Dee Williams, and Richard Pryor, is based on the Indianapolis Clowns.

By 1966 the Indianapolis Clowns were the last Negro league team still playing. The Clowns continued to play exhibition games into the 1980s, but as a humorous sideshow rather than a competitive sport. After many years on the road as a barnstorming team, the Clowns finally disbanded in 1989. The Clowns were also the first team to feature women as umpires. The 1976 movie “The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings”, starring James Earl Jones, Billy Dee Williams, and Richard Pryor, is based on the Indianapolis Clowns.

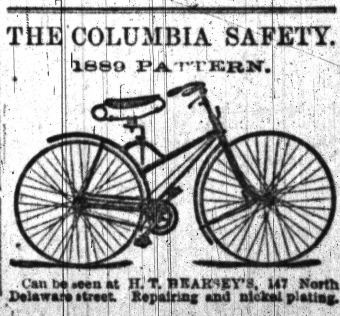

Although the first documented appearance of a bicycle in Indianapolis can be traced to a demonstration of the high-wheeled bike called the “Ordinary” in 1869, these old fashioned contraptions (known back then as “Velocipedes”) would be almost unrecognizable to the riders of today. With their huge front tires and seats that seemed to require a ladder to climb up to, these early bikes were awkward and unwieldy for use by all but the most hardy of daredevil souls (They didn’t call them “boneshakers” for nothing back then). It would take nearly 25 years after the close of the American Civil War before the bike began to resemble the form most familiar to riders of today. The development of the safety bike with it’s 2 equal-sized wheels in the 1880s made the new sport more acceptable as a hobby and pastime.

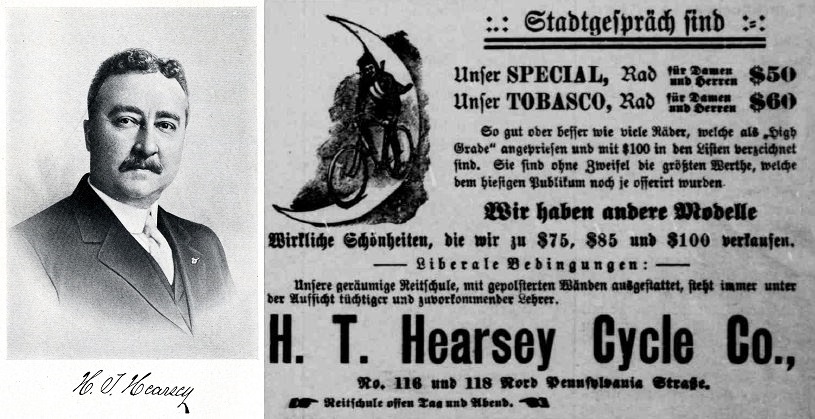

Although the first documented appearance of a bicycle in Indianapolis can be traced to a demonstration of the high-wheeled bike called the “Ordinary” in 1869, these old fashioned contraptions (known back then as “Velocipedes”) would be almost unrecognizable to the riders of today. With their huge front tires and seats that seemed to require a ladder to climb up to, these early bikes were awkward and unwieldy for use by all but the most hardy of daredevil souls (They didn’t call them “boneshakers” for nothing back then). It would take nearly 25 years after the close of the American Civil War before the bike began to resemble the form most familiar to riders of today. The development of the safety bike with it’s 2 equal-sized wheels in the 1880s made the new sport more acceptable as a hobby and pastime. In 1887 bicycle mechanic and expert rider Henry T. Hearsey (1863-1939) opened the first bicycle showroom in Indianapolis. His store was located at the intersection of Delaware and New York Streets on the city’s near eastside. Hearsey introduced the first safety bike to Indianapolis, the English-made Rudge, which sold for the princely sum of $150 (roughly $4,000 in today’s money). Keep in mind that was about twice the price of a horse and buggy at the time. He would later open a larger shop at 116-118 North Pennsylvania Street. He is credited for introducing the 1st safety bicycle in the Capitol city in 1889. Hoosiers took to it immediately and within a few short years, the streets of Indy were so clogged with bicyclists that the City Council passed a bicycle licensing ordinance requiring a $ 1 license fee for every bicycle in the city.

In 1887 bicycle mechanic and expert rider Henry T. Hearsey (1863-1939) opened the first bicycle showroom in Indianapolis. His store was located at the intersection of Delaware and New York Streets on the city’s near eastside. Hearsey introduced the first safety bike to Indianapolis, the English-made Rudge, which sold for the princely sum of $150 (roughly $4,000 in today’s money). Keep in mind that was about twice the price of a horse and buggy at the time. He would later open a larger shop at 116-118 North Pennsylvania Street. He is credited for introducing the 1st safety bicycle in the Capitol city in 1889. Hoosiers took to it immediately and within a few short years, the streets of Indy were so clogged with bicyclists that the City Council passed a bicycle licensing ordinance requiring a $ 1 license fee for every bicycle in the city.

the nickname “Major”, which stuck with him the rest of his life. He has been widely acknowledged as the first American International superstar of bicycle racing. He was the first African American to achieve the level of world champion and the second black athlete to win a world championship in any sport. Carl Fisher was one of the founders of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, developer of the city of Miami and the creator of the famous “Lincoln Highway” and the “Dixie Highway.”

the nickname “Major”, which stuck with him the rest of his life. He has been widely acknowledged as the first American International superstar of bicycle racing. He was the first African American to achieve the level of world champion and the second black athlete to win a world championship in any sport. Carl Fisher was one of the founders of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, developer of the city of Miami and the creator of the famous “Lincoln Highway” and the “Dixie Highway.”

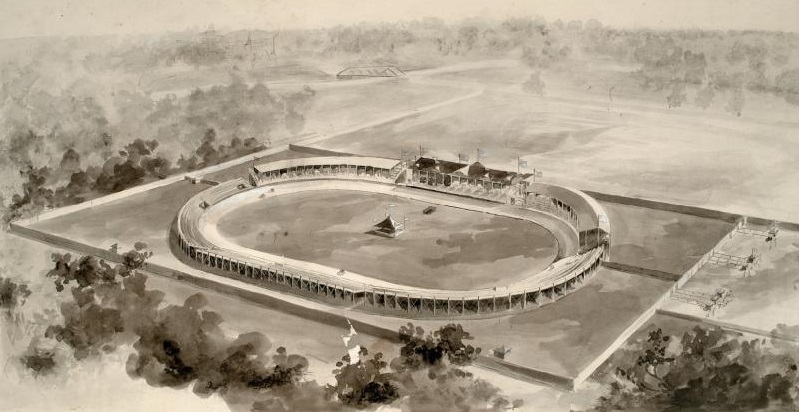

Cycling was so popular in Indianapolis that the city constructed a racing track known as the “Newby Oval” located near 30th Street and Central Avenue in 1898. The track was designed by Shortridge graduate Herbert Foltz who also designed the Broadway Methodist Church, Irvington United Methodist Church and the Meridian Heights Presbyterian Church. Foltz would also design the new Shortridge High School at 34th and Meridian. The state of the art cycling facility could, and often did, seat 20,000 and hosted several national championships sponsored by the chief sanctioning body, “The League of American Wheelmen.” The American Wheelmen often got involved in local and national politics. Hoosier wheelmen raced into the William McKinley presidential campaign in 1896 and helped him win the election. With this new found political clout, riding clubs began to put pressure on politicians to improve urban streets and rural roads, exclaiming “We are a factor in politics, and demand that the great cause of Good Roads be given consideration.”

Cycling was so popular in Indianapolis that the city constructed a racing track known as the “Newby Oval” located near 30th Street and Central Avenue in 1898. The track was designed by Shortridge graduate Herbert Foltz who also designed the Broadway Methodist Church, Irvington United Methodist Church and the Meridian Heights Presbyterian Church. Foltz would also design the new Shortridge High School at 34th and Meridian. The state of the art cycling facility could, and often did, seat 20,000 and hosted several national championships sponsored by the chief sanctioning body, “The League of American Wheelmen.” The American Wheelmen often got involved in local and national politics. Hoosier wheelmen raced into the William McKinley presidential campaign in 1896 and helped him win the election. With this new found political clout, riding clubs began to put pressure on politicians to improve urban streets and rural roads, exclaiming “We are a factor in politics, and demand that the great cause of Good Roads be given consideration.”

Although I never fail to take my annual trip around Monument Circle at Christmastime to gaze in wonder at the fantastic fir tree fantasy, my personal memories of Christmas on the Circle revolve around a little shack that used to rest at its base facing the Indiana Statehouse. You may think of the L.S. Ayres Cherub, Santa’s mailbox, the 26 larger-than-life toy soldiers and sailors surrounding the Circle, the 26 red & white striped peppermint sticks, the 52 garland strands or the 4,784 colored lights strung from the top of the Monument to its base, but I think of the Roselyn Bakery Christmas Hut.

Although I never fail to take my annual trip around Monument Circle at Christmastime to gaze in wonder at the fantastic fir tree fantasy, my personal memories of Christmas on the Circle revolve around a little shack that used to rest at its base facing the Indiana Statehouse. You may think of the L.S. Ayres Cherub, Santa’s mailbox, the 26 larger-than-life toy soldiers and sailors surrounding the Circle, the 26 red & white striped peppermint sticks, the 52 garland strands or the 4,784 colored lights strung from the top of the Monument to its base, but I think of the Roselyn Bakery Christmas Hut. Decorated with Gingerbread man shutters and candy cane pillars, coated in what looked like white icing, the Christmas hut was set up on the West side of the Circle where it remained for 25 years from 1974 to 1999. It was estimated that some 1.2 million Gingerbread man cookies were handed out from within that festive little house over those years. Just like the bakery itself, that little hut was an institution.

Decorated with Gingerbread man shutters and candy cane pillars, coated in what looked like white icing, the Christmas hut was set up on the West side of the Circle where it remained for 25 years from 1974 to 1999. It was estimated that some 1.2 million Gingerbread man cookies were handed out from within that festive little house over those years. Just like the bakery itself, that little hut was an institution.

For me, Roselyn will always be identified for buttermilk jumbles, toffee cookies, alligator & sweetheart coffee cakes, yeast donuts and the darling little girl cartoon mascot known as “Rosie”. A blonde haired, blue eyed perpetually smiling little naive whose popularity forced the Roselyn Christmas Hut to undergo a name change to “Rosie’s Gingerbread House.” If memory serves, for a time there was even a living, breathing life-sized “Rosie” mascot dressed in a horribly oversized paper mache’ head and wearing a red velvet dress. Every so often, she would wobble awkwardly out of the Gingerbread hut to personally pass out cookies to the eager, but slightly befuddled, kiddies on the Circle. As I recall, she didn’t speak, but to a 12-year-old cartoon addicted boy like me, her skirt was short and her cookies were hot.

For me, Roselyn will always be identified for buttermilk jumbles, toffee cookies, alligator & sweetheart coffee cakes, yeast donuts and the darling little girl cartoon mascot known as “Rosie”. A blonde haired, blue eyed perpetually smiling little naive whose popularity forced the Roselyn Christmas Hut to undergo a name change to “Rosie’s Gingerbread House.” If memory serves, for a time there was even a living, breathing life-sized “Rosie” mascot dressed in a horribly oversized paper mache’ head and wearing a red velvet dress. Every so often, she would wobble awkwardly out of the Gingerbread hut to personally pass out cookies to the eager, but slightly befuddled, kiddies on the Circle. As I recall, she didn’t speak, but to a 12-year-old cartoon addicted boy like me, her skirt was short and her cookies were hot. a long way baby.”

a long way baby.” Eight mayors and ten governors have served our city and state over the past 50 years. I can’t say that I miss any of them, but I do miss those Gingerbread cookies. If you do too, you can make them yourself. Here’s the recipe for Roselyn Bakeries famous Gingerbread Men cookies: 1 1/4 teaspoon allspice, 2 3/4 teaspoons baking soda, 5 teaspoons ground cinnamon, 1 teaspoon ground cloves, 1 teaspoon ground ginger, 2 1/2 teaspoons salt, 3/4 cup Crisco shortening, 3/4 cup granulated sugar, 6 tablespoons whole eggs, 1 1/4 cup extra fine coconut (Make sure that the coconut you use is very fine, almost like coarse sugar-you may have to grind store bought coconut flake down), 1 1/4 cup honey, 5 cups all-purpose flour. Preheat oven to 360 degrees F. Combine allspice, baking soda, cinnamon, cloves, ginger, salt, shortening, and sugar into a large mixing bowl. Cream together. Scrape down bowl. Add beaten eggs and mix thoroughly.

Eight mayors and ten governors have served our city and state over the past 50 years. I can’t say that I miss any of them, but I do miss those Gingerbread cookies. If you do too, you can make them yourself. Here’s the recipe for Roselyn Bakeries famous Gingerbread Men cookies: 1 1/4 teaspoon allspice, 2 3/4 teaspoons baking soda, 5 teaspoons ground cinnamon, 1 teaspoon ground cloves, 1 teaspoon ground ginger, 2 1/2 teaspoons salt, 3/4 cup Crisco shortening, 3/4 cup granulated sugar, 6 tablespoons whole eggs, 1 1/4 cup extra fine coconut (Make sure that the coconut you use is very fine, almost like coarse sugar-you may have to grind store bought coconut flake down), 1 1/4 cup honey, 5 cups all-purpose flour. Preheat oven to 360 degrees F. Combine allspice, baking soda, cinnamon, cloves, ginger, salt, shortening, and sugar into a large mixing bowl. Cream together. Scrape down bowl. Add beaten eggs and mix thoroughly. Scrape down bowl. Add coconut and honey and mix well. Scrape down bowl. Add flour and mix well. On a lightly floured surface, with a floured rolling pin, roll dough 1/8 inch thick. With a 5 inch long cutter, cut out men. Re-roll trimmings and cut more cookies. With spatula, place 1/2 inch apart on cookie sheets. Bake at 360 degrees for 8 minutes or until browned, then, with spatula, remove cookies to racks to cool. Decorate as desired. Makes 3 dozen cookies. Now if I could only locate a slightly used Christmas shack.

Scrape down bowl. Add coconut and honey and mix well. Scrape down bowl. Add flour and mix well. On a lightly floured surface, with a floured rolling pin, roll dough 1/8 inch thick. With a 5 inch long cutter, cut out men. Re-roll trimmings and cut more cookies. With spatula, place 1/2 inch apart on cookie sheets. Bake at 360 degrees for 8 minutes or until browned, then, with spatula, remove cookies to racks to cool. Decorate as desired. Makes 3 dozen cookies. Now if I could only locate a slightly used Christmas shack.