Original publish date: March 21, 2019

Spring training baseball is back. I am one of those legion of fans who wait every year to hear the five most beautiful words in the English language: “Pitchers and Catchers Report.” As a kid growing up, spring training baseball was always synonymous with Florida. In the Mid-1970s, my family took our spring break vacations at the Island Towers resort hotel in Fort Myers. It just so happened that the hotel was the spring training headquarters of the Kansas City Royals. So it was no big thing seeing guys like George Brett, Frank White, Freddie Patek, and Cookie Rojas hanging out at the pool or chasing my older sisters on the beach. Years later, I ran into Jamie Quirk at old 16th Street Bush Stadium and he informed me that the Island Towers were owned by Buck Martinez’s parents.

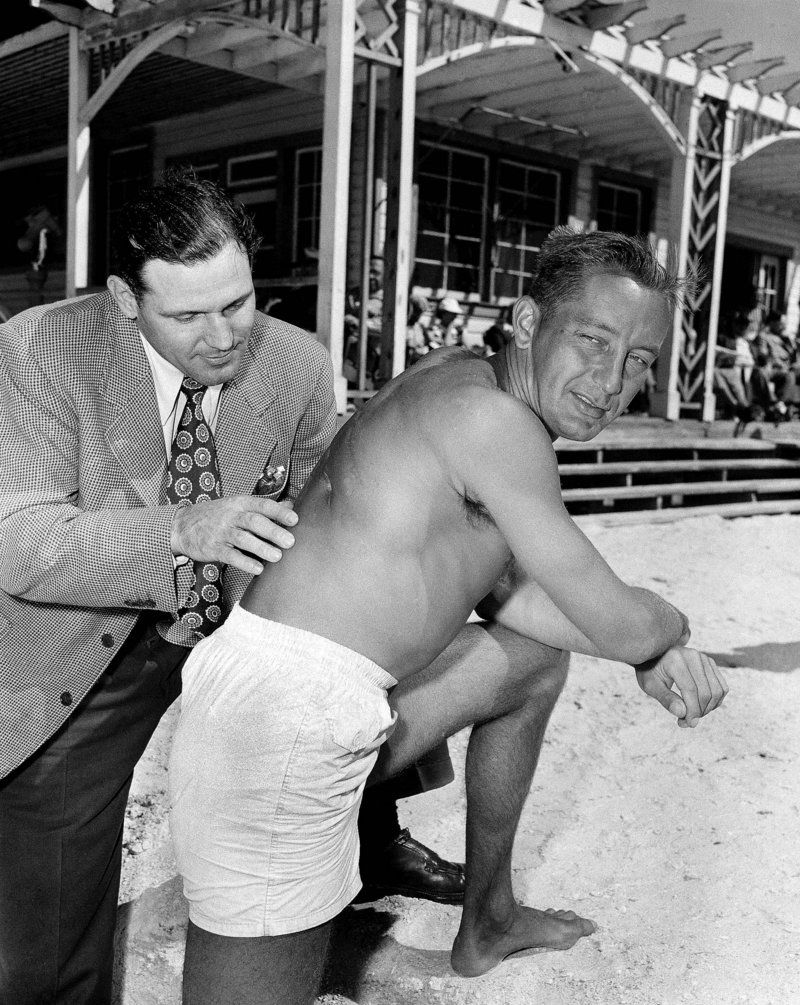

My grandparents retired to Cape Coral in the late 1970s and I recall one of their oldster neighbors showing me a photo album from the 1930s with pictures of the New York Yankees at Spring Training down there. Turns out his family lived near the facility, Fort Lauderdale if memory serves, where the Yankees trained. I can remember the photos in there of Lou Gehrig in a bathing suit (MAN that dude was HUGE!) and Babe Ruth in full uniform on the beach, two bats resting on his shoulder with his fielder’s glove and cleats hanging from the back like a hobo pouch. In his pin striped uniform! On the Beach! Everything in that photo would be worth a small fortune today, including the photo itself!

My grandparents retired to Cape Coral in the late 1970s and I recall one of their oldster neighbors showing me a photo album from the 1930s with pictures of the New York Yankees at Spring Training down there. Turns out his family lived near the facility, Fort Lauderdale if memory serves, where the Yankees trained. I can remember the photos in there of Lou Gehrig in a bathing suit (MAN that dude was HUGE!) and Babe Ruth in full uniform on the beach, two bats resting on his shoulder with his fielder’s glove and cleats hanging from the back like a hobo pouch. In his pin striped uniform! On the Beach! Everything in that photo would be worth a small fortune today, including the photo itself!

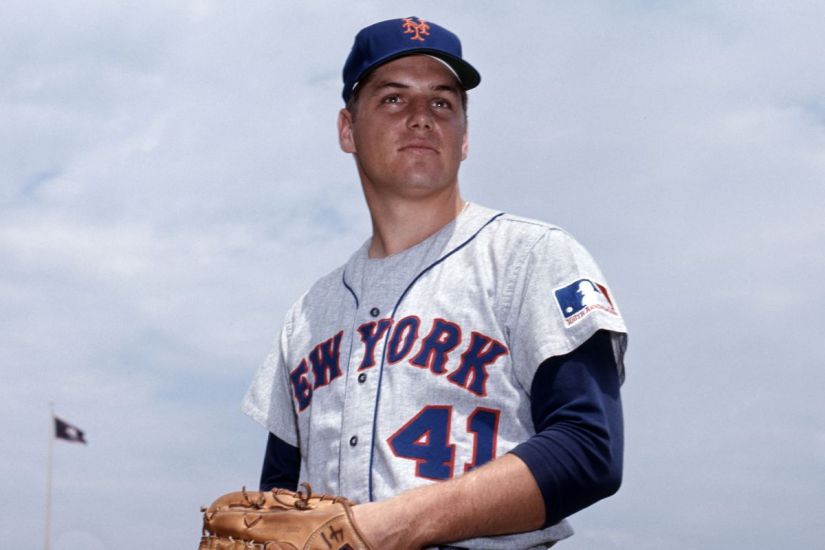

Somehow, I became a Blue Jays fan. Probably because I went to their first spring training game in franchise history in Dunedin. March 11, 1977 they beat the Mets 3-1 at Grant Field, which was built in 1930 and looked like it. I went to a few games that year. I distinctly recall sitting on a wooden bleacher seat right next to Tom Seaver who was talking to me like it was no big deal. And he was pitching that day. Within a few weeks, he was traded to the Cincinnati Reds “Big Red Machine.” Florida meant Spring Training, period. Somewhere along the line that changed.

Somehow, I became a Blue Jays fan. Probably because I went to their first spring training game in franchise history in Dunedin. March 11, 1977 they beat the Mets 3-1 at Grant Field, which was built in 1930 and looked like it. I went to a few games that year. I distinctly recall sitting on a wooden bleacher seat right next to Tom Seaver who was talking to me like it was no big deal. And he was pitching that day. Within a few weeks, he was traded to the Cincinnati Reds “Big Red Machine.” Florida meant Spring Training, period. Somewhere along the line that changed.

They had spring training games in Arizona, something called the “Cactus League”, but that didn’t count for much back then. Today, more teams call Arizona home for spring training than ever before. The teams that play in Arizona now are the Diamondbacks, Chicago Cubs & White Sox, Cincinnati Reds, Cleveland Indians, Colorado Rockies, Kansas City Royals, Los Angeles Angels and Dodgers, Milwaukee Brewers, Oakland Athletics, San Diego Padres, San Francisco Giants, Seattle Mariners, and Texas Rangers. More than 100 games are scheduled between Feb. 21 – March 26, 2019. The broadcasters say that the travel in Florida is brutal, sometimes 3-4 hour bus rides, while the travel between stadiums in Arizona is usually less than an hour. When it comes to Arizona baseball, I think of a spring training story from the Cactus League that happened before I was born. The story emanates from Hi Corbett Field in spring training of 1961. But first a little background.

March of 1961 was a busy time: America’s brand new President John F. Kennedy creates the Peace Corps, The Beatles start performing at the Cavern Club, Nine African-American students from Mississippi’s Tougaloo College made the first peaceful attempt to end segregation by staging a “read-in” at the whites-only main branch of the Jackson municipal public library, NASA launches a Mercury-Redstone BD rocket from Cape Canaveral as one final test flight to certify its safety for human transport. Alan Shepard had volunteered to take the flight and become the first man to travel into outer space, but was stopped by Wernher von Braun from going, Less than three weeks later, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin would, on April 12, would reach the milestone, Actor Ronald Reagan bursts onto the political scene with his speech “Encroaching Control” before the Phoenix chamber of commerce and the Boston Strangler Albert DeSalvo is captured.

March of 1961 was a busy time: America’s brand new President John F. Kennedy creates the Peace Corps, The Beatles start performing at the Cavern Club, Nine African-American students from Mississippi’s Tougaloo College made the first peaceful attempt to end segregation by staging a “read-in” at the whites-only main branch of the Jackson municipal public library, NASA launches a Mercury-Redstone BD rocket from Cape Canaveral as one final test flight to certify its safety for human transport. Alan Shepard had volunteered to take the flight and become the first man to travel into outer space, but was stopped by Wernher von Braun from going, Less than three weeks later, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin would, on April 12, would reach the milestone, Actor Ronald Reagan bursts onto the political scene with his speech “Encroaching Control” before the Phoenix chamber of commerce and the Boston Strangler Albert DeSalvo is captured.

Hi Corbett Field is located in Tucson, Arizona. Opened in 1937, it was originally called Randolph Municipal Baseball Park. In 1951, it was renamed in honor of Hiram Stevens Corbett (1886–1967), a former Arizona state senator who was instrumental in bringing spring training to Tucson, specifically by convincing Bill Veeck to bring the Cleveland Indians there in 1947. Veeck owned a ranch in Tucson, and he and players sometimes rode horses there after games. Veeck claimed that he moved the team’s training camp from Florida to Arizona in order to avoid Florida’s Jim Crow laws.

In the mid-1940s, while Veeck was owner of the then-minor league Milwaukee Brewers of the AAA American Association, during one of his team’s spring games in Ocala, Florida, the owner took a bleacher seat and started talking with the fans around him. Veeck had no idea that he had sat in the part of the stadium that was designated for African American fans. That turned out to be a big deal in the segregated “Jim Crow” South of the 1940s. Veeck had no idea that he was breaking a law that kept black fans from mixing with white spectators. In his book, “Veeck as in Wreck”, he wrote, “Within a few minutes, a sheriff came running over to tell me I couldn’t sit there.” The Brewers owner refused to move, and soon the mayor himself was threatening to force him to sit in another section. Veeck countered that if they wanted him to move from his seat, he would would move his team right along with him; to another city. The mayor finally backed down, but Veeck never forgot it.

In time, Veeck sold his stake in the Brewers and bought the Cleveland Indians. Veeck chose Phoenix, Arizona as the Indians’ spring training home for 1947. Veeck convinced the New York Giants to join his Indians so that the two teams could prepare for the season. The next season, Veeck signed Larry Doby to a contract, making him the American League’s first black player. Doby made his major league debut with the Indians on July 5, 1947, about 11 weeks after Robinson’s first game with the Brooklyn Dodgers. The Giants followed by signing Hall of Famer Monte Irvin the next year and the Cactus League was born.

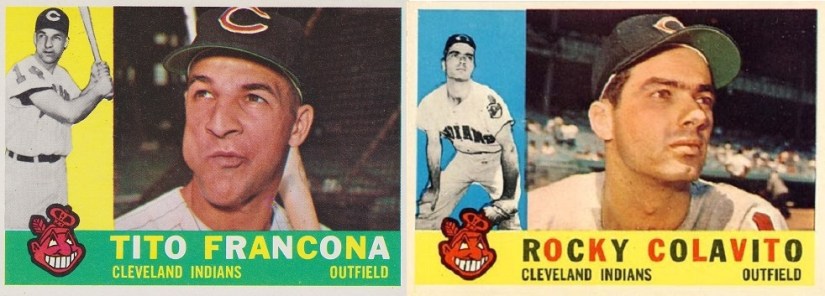

Last year, John Patsy Francona, a Cleveland Indians fan favorite better known as “Tito” died on the eve of spring training. It was the day before Valentine’s Day and the Indians’ pitchers & catchers were just trickling in to their spring training park in Goodyear, Arizona. The passing was made all the more bittersweet when you consider that the team was managed by Tito’s son, Terry Francona. Terry grew up in the Indians dugout where players called him “Little Tito.” As a member of the Montreal Expos, Terry played against our Indians here in Indianapolis at the old 16th street stadium. Before that he played college ball for Arizona State and led his team to the 1980 College World Series Championship. Terry Francona’s dad’s nickname of “Tito” was naturally passed down to his son, and although the broadcasters and news media still call him “Terry”, Tito is what the manager’s friends and players call him.

Last year, John Patsy Francona, a Cleveland Indians fan favorite better known as “Tito” died on the eve of spring training. It was the day before Valentine’s Day and the Indians’ pitchers & catchers were just trickling in to their spring training park in Goodyear, Arizona. The passing was made all the more bittersweet when you consider that the team was managed by Tito’s son, Terry Francona. Terry grew up in the Indians dugout where players called him “Little Tito.” As a member of the Montreal Expos, Terry played against our Indians here in Indianapolis at the old 16th street stadium. Before that he played college ball for Arizona State and led his team to the 1980 College World Series Championship. Terry Francona’s dad’s nickname of “Tito” was naturally passed down to his son, and although the broadcasters and news media still call him “Terry”, Tito is what the manager’s friends and players call him.

The elder Francona arrived in Cleveland in 1959 with baby Terry (born April 22 of that year) in tow. That season, Tito was at the top of his game and his presence knocked some all-time Indian greats right off the roster. Francona came to Cleveland in a one-for-one trade that sent Hall of Famer Larry Doby to the White Sox. (Ironically, it was the second time Tito had been traded for Larry Doby after the O’s traded him to the White Sox in 1958) Tito arrived at the “Mistake on the Lake” with big shoes to fill, but Francona, who began the 1959 season as a pinch hitter and utility man, quickly earned a regular place in the lineup. After going five-for-nine with a home run in a June 7 doubleheader against the Yankees, Francona replaced Jim Piersall as Cleveland’s starting center fielder. By the end of the season, he displaced Indians regular first baseman Vic Power, who was shifted to second base.

That season Tito batted .363 with a career high twenty home runs and 79 RBIs to help the Indians to an 89–65 record and second place in the American League. His .363 average would have led the league, however, he fell 34 at-bats short of the 3.1 per game necessary to qualify. The batting championship went to the Detroit Tigers’ Harvey Kuenn, with a .353 batting average, ten points below Tito. Francona finished fifth in balloting for the AL Most Valuable Player Award that season. He compiled 20 home runs, 17 doubles, 79 RBIs, 68 runs scored, 145 hits, a .414 on-base percentage and a .566 slugging percentage in 122 games.

That season Tito batted .363 with a career high twenty home runs and 79 RBIs to help the Indians to an 89–65 record and second place in the American League. His .363 average would have led the league, however, he fell 34 at-bats short of the 3.1 per game necessary to qualify. The batting championship went to the Detroit Tigers’ Harvey Kuenn, with a .353 batting average, ten points below Tito. Francona finished fifth in balloting for the AL Most Valuable Player Award that season. He compiled 20 home runs, 17 doubles, 79 RBIs, 68 runs scored, 145 hits, a .414 on-base percentage and a .566 slugging percentage in 122 games.

Ironically, the next season, Francona was shifted to left field when the Indians traded home run leader Rocky Colavito for Kuenn, the same player who edged out Tito for the batting title the year before. With former Indianapolis Indians slugger Colavito gone (Indianapolis was Cleveland’s minor league affiliate from 1952-56), Francona was inserted in the clean-up spot in manager Joe Gordon’s batting order. Tito tallied only six home runs through the All-Star break and was dropped to the number six spot in the batting order for August, and then back up to number two by September. Tito hit eleven home runs over the rest of the season to finish with seventeen overall. He batted ,292 and his 36 doubles led the American League for 1960. The trade of Colavito for Kuenn is considered by longtime Indians’ fans the beginning of the “Curse of Rocky Colavito” and as you might imagine, Tito Francona was right in the thick of it.

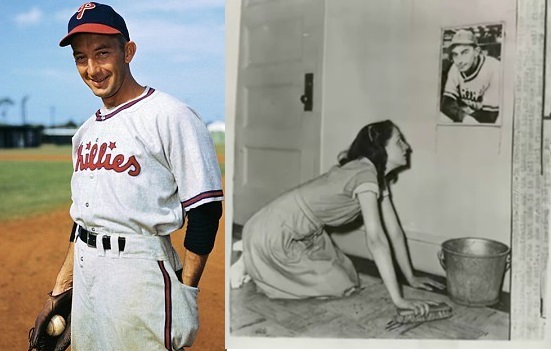

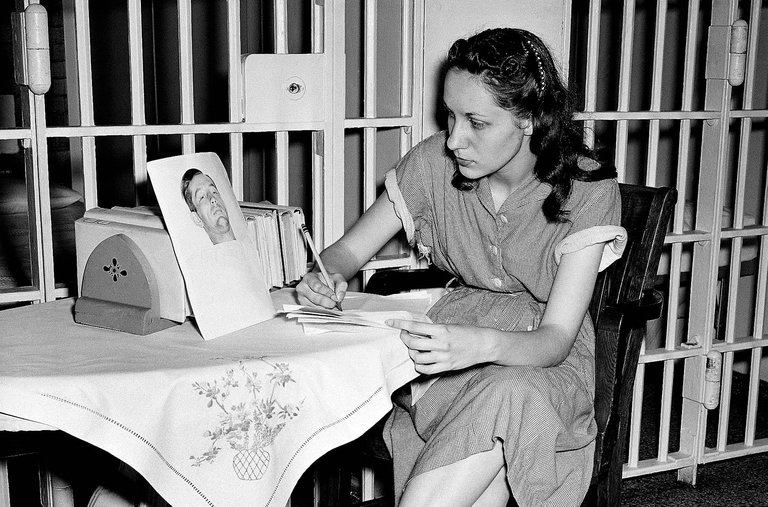

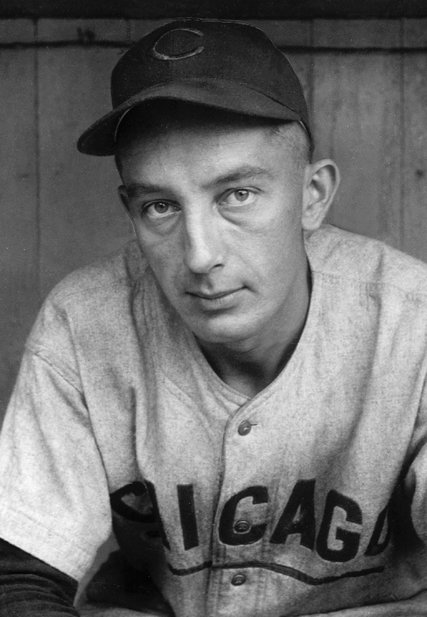

individual player. On June 14, 1949 Philadelphia Phillies “Whiz Kids” (and former Chicago Cub) first baseman Eddie Waitkus was shot by an obsessed fan named Ruth Ann Steinhagen in a Chicago Hotel Room. The comparison between Waitkus and the movie character pretty much ends there. But it is a Helluva story.

individual player. On June 14, 1949 Philadelphia Phillies “Whiz Kids” (and former Chicago Cub) first baseman Eddie Waitkus was shot by an obsessed fan named Ruth Ann Steinhagen in a Chicago Hotel Room. The comparison between Waitkus and the movie character pretty much ends there. But it is a Helluva story.

The Waitkus shooting is regarded as the inspiration for Bernard Malamud’s 1952 baseball book The Natural, which was made into a film by Barry Levinson in 1984. Other than the shooting, its hard to make a comparison between Eddie Waitkus and Roy Hobbs, the character played by Robert Redford in the film. In The Natural, Hobbs was shot as a teenage phenom before ever reaching the majors and the shooting kept him from reaching the big leagues until the age of 34, at which point he immediately started hitting like Babe Ruth with his miracle bat “Wonder Boy”. When shot, Waitkus was a 29-year-old veteran of both World War II and 448 major league games.

The Waitkus shooting is regarded as the inspiration for Bernard Malamud’s 1952 baseball book The Natural, which was made into a film by Barry Levinson in 1984. Other than the shooting, its hard to make a comparison between Eddie Waitkus and Roy Hobbs, the character played by Robert Redford in the film. In The Natural, Hobbs was shot as a teenage phenom before ever reaching the majors and the shooting kept him from reaching the big leagues until the age of 34, at which point he immediately started hitting like Babe Ruth with his miracle bat “Wonder Boy”. When shot, Waitkus was a 29-year-old veteran of both World War II and 448 major league games. Miraculous comeback aside, Waitkus, who died in 1972, was no Hobbs at the bat. Though he was enjoying his finest season when he was shot, he had just one home run in 246 plate appearances, and when he retired in 1955 at age 35, he had just 24 home runs in 4,681 at bats. Waitkus hit for respectable averages (.304 in 1946, .306 in 1949 before the shooting, .285 for his career), but they were empty. He hit for little power and drew only an average number of walks. He did make a pair of All-Star teams and drew some low-ballot MVP votes in two seasons, but was by no means a Hall of Fame candidate.

Miraculous comeback aside, Waitkus, who died in 1972, was no Hobbs at the bat. Though he was enjoying his finest season when he was shot, he had just one home run in 246 plate appearances, and when he retired in 1955 at age 35, he had just 24 home runs in 4,681 at bats. Waitkus hit for respectable averages (.304 in 1946, .306 in 1949 before the shooting, .285 for his career), but they were empty. He hit for little power and drew only an average number of walks. He did make a pair of All-Star teams and drew some low-ballot MVP votes in two seasons, but was by no means a Hall of Fame candidate.

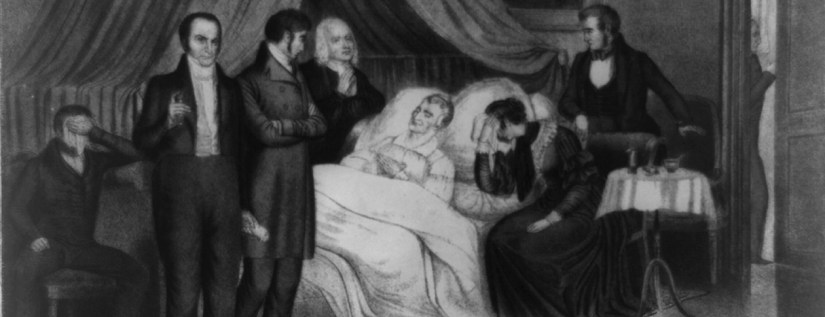

The first order of business was to hide the fact from Devin’s widowed mother until the body could be recovered, and the second was to take precautions for safeguarding John Scott Harrison’s remains. Benjamin Harrison and his younger brother John carefully supervised the lowering of his father’s body into an eight-foot-long grave. At the bottom, they placed the state-of-the-art metallic casket into a secure brick vault with thick walls and a solid stone bottom. Three flat stones, eight or more inches thick were procured for a cover. With great difficulty the stones were lowered over the casket, the largest at the upper end and the two smaller slabs crosswise at the foot. All three of these slabs were carefully cemented together. The brothers waited patiently beside the open hole for several hours as the cement dried. Finally, with their father’s remains still under guard, a massive amount of dirt was shoveled into the hole and the brothers departed secure in the notion that their father would rest in peace for all eternity.

The first order of business was to hide the fact from Devin’s widowed mother until the body could be recovered, and the second was to take precautions for safeguarding John Scott Harrison’s remains. Benjamin Harrison and his younger brother John carefully supervised the lowering of his father’s body into an eight-foot-long grave. At the bottom, they placed the state-of-the-art metallic casket into a secure brick vault with thick walls and a solid stone bottom. Three flat stones, eight or more inches thick were procured for a cover. With great difficulty the stones were lowered over the casket, the largest at the upper end and the two smaller slabs crosswise at the foot. All three of these slabs were carefully cemented together. The brothers waited patiently beside the open hole for several hours as the cement dried. Finally, with their father’s remains still under guard, a massive amount of dirt was shoveled into the hole and the brothers departed secure in the notion that their father would rest in peace for all eternity. John Harrison shrugged off the discovery knowing that his cousin Augustus Devin, the subject of their search, was a very young man. Still, the body was lain flat on the floor and the cloth was cast aside with the aid of a nearby stick. As the dead man’s face was revealed, John Harrison gasped in horror that the dead body was none other than that of his father, John Scott Harrison.

John Harrison shrugged off the discovery knowing that his cousin Augustus Devin, the subject of their search, was a very young man. Still, the body was lain flat on the floor and the cloth was cast aside with the aid of a nearby stick. As the dead man’s face was revealed, John Harrison gasped in horror that the dead body was none other than that of his father, John Scott Harrison.

is a rope with a hook at one end, a short crowbar, and a spade and a pick. He generally has a “pard,” as it is easier to hunt in couples. He is notified of the “plant” (body), and by personal inspection makes himself familiar with all the surroundings, before the attempt is made. The pick and spade remove the earth from the grave as far as the widest part of the coffin, and with the crowbar, the coffin is shattered, and the rope with the hook end fastened around the cadaver’s neck, when it is drawn out through the hole without disturbing the earth elsewhere. As soon as the cadaver is sacked, the earth replaced, and the grave made to look as near like it was as possible. There are some bunglers however, who have been guilty of leaving the grave open, with fragments of the cadaver’s clothing lying around. They are a disgrace to the profession, and have done much to foster an unfriendly public sentiment in this city.”

is a rope with a hook at one end, a short crowbar, and a spade and a pick. He generally has a “pard,” as it is easier to hunt in couples. He is notified of the “plant” (body), and by personal inspection makes himself familiar with all the surroundings, before the attempt is made. The pick and spade remove the earth from the grave as far as the widest part of the coffin, and with the crowbar, the coffin is shattered, and the rope with the hook end fastened around the cadaver’s neck, when it is drawn out through the hole without disturbing the earth elsewhere. As soon as the cadaver is sacked, the earth replaced, and the grave made to look as near like it was as possible. There are some bunglers however, who have been guilty of leaving the grave open, with fragments of the cadaver’s clothing lying around. They are a disgrace to the profession, and have done much to foster an unfriendly public sentiment in this city.” THE MOST FRUITFUL FIELDS: “The most of the stiffs are raised at Greenlawn cemetery (in Franklin, south of the city), at the Mt. Jackson cemetery (on the grounds of Central State hospital), and at the Poor Farm cemetery (Northwest of the city). So far as I know Crown Hill has never been troubled. Many of the village cemeteries in the neighboring counties are also visited, however, and made to contribute their quota to the cause of science. Some of these village cadavers are those of people who moved in the best society, and besides their value in material for dissection, are rich in jewelry, laces, velvets, etc. The hair of a female subject is alone worth $25. Nothing is wasted, you may be sure. Even the ornaments on the coffin lids are used again..”

THE MOST FRUITFUL FIELDS: “The most of the stiffs are raised at Greenlawn cemetery (in Franklin, south of the city), at the Mt. Jackson cemetery (on the grounds of Central State hospital), and at the Poor Farm cemetery (Northwest of the city). So far as I know Crown Hill has never been troubled. Many of the village cemeteries in the neighboring counties are also visited, however, and made to contribute their quota to the cause of science. Some of these village cadavers are those of people who moved in the best society, and besides their value in material for dissection, are rich in jewelry, laces, velvets, etc. The hair of a female subject is alone worth $25. Nothing is wasted, you may be sure. Even the ornaments on the coffin lids are used again..” The night was a graverobber’s best friend. He lived in it, worked in it, played in it and hid in it. Late at night, these ghouls would steal into cemeteries where a burial had just taken place. In general, fresh graves were best, since the earth had not yet settled and digging was easy work. Laying a sheet or tarp beside the grave, the dirt was shoveled on top of it so the nearby grounds were undisturbed. Most body snatchers could remove the body in less time than it took most people to saddle a horse. They would carefully cover the telltale hole with dirt again, making sure the grave looked the same as it had before they came. Then hurriedly take the body away via the alleyways and sewers of the city, finally delivering the anonymous dearly departed to the back door of a medical school. In time, several of these ghouls began to furnish fresh corpses for sale by murdering the poor, homeless citizens of the city who once stood silent vigil in the alleys as the graverobbers crept past with their macabre cargo in tow.

The night was a graverobber’s best friend. He lived in it, worked in it, played in it and hid in it. Late at night, these ghouls would steal into cemeteries where a burial had just taken place. In general, fresh graves were best, since the earth had not yet settled and digging was easy work. Laying a sheet or tarp beside the grave, the dirt was shoveled on top of it so the nearby grounds were undisturbed. Most body snatchers could remove the body in less time than it took most people to saddle a horse. They would carefully cover the telltale hole with dirt again, making sure the grave looked the same as it had before they came. Then hurriedly take the body away via the alleyways and sewers of the city, finally delivering the anonymous dearly departed to the back door of a medical school. In time, several of these ghouls began to furnish fresh corpses for sale by murdering the poor, homeless citizens of the city who once stood silent vigil in the alleys as the graverobbers crept past with their macabre cargo in tow. In the late 1800s in Indiana, it has been estimated that between 80 to 120 bodies each year were purchased from grave robbers to be used for medical instruction at medical schools and teaching facilities in Indianapolis. An end to the “big business” of grave robbing came as a result of twentieth-century legislation in Indiana which allowed individuals to donate their bodies for this purpose. In 1903, the Indiana General Assembly enacted legislation that created the state anatomical board that was empowered to receive unclaimed bodies from throughout the state and distribute them to medical schools. The act was “for the promotion of anatomical science and to prevent grave desecration.”

In the late 1800s in Indiana, it has been estimated that between 80 to 120 bodies each year were purchased from grave robbers to be used for medical instruction at medical schools and teaching facilities in Indianapolis. An end to the “big business” of grave robbing came as a result of twentieth-century legislation in Indiana which allowed individuals to donate their bodies for this purpose. In 1903, the Indiana General Assembly enacted legislation that created the state anatomical board that was empowered to receive unclaimed bodies from throughout the state and distribute them to medical schools. The act was “for the promotion of anatomical science and to prevent grave desecration.”

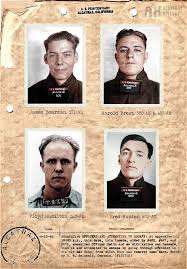

What didn’t change was the fact that 24-year-old Indianapolis resident and “baby” of the Alcatraz escape outfit, James A. Boarman was dead, the victim of the prison guards’ gunfire. Ranger John Cantwell took me to the old Model Industries Building, now off limits to the public and home to the protected nesting California waterfowl that populate the island in summertime, to show me the approximate place of Boarman’s demise. Over his years of service, Cantwell has become an expert on Alcatraz escapes and the 34 men who attempted them. One former inmate, “Alcatraz from the Inside” author Jim Quillen, was a close friend of Cantwell’s. The dedicated park ranger did not miss the opportunity to ask Quillen about that 1943 escape. Quillen, a bank robber and kidnapper imprisoned on the island for ten years from 1942 to 1952, knew James Boarman.

What didn’t change was the fact that 24-year-old Indianapolis resident and “baby” of the Alcatraz escape outfit, James A. Boarman was dead, the victim of the prison guards’ gunfire. Ranger John Cantwell took me to the old Model Industries Building, now off limits to the public and home to the protected nesting California waterfowl that populate the island in summertime, to show me the approximate place of Boarman’s demise. Over his years of service, Cantwell has become an expert on Alcatraz escapes and the 34 men who attempted them. One former inmate, “Alcatraz from the Inside” author Jim Quillen, was a close friend of Cantwell’s. The dedicated park ranger did not miss the opportunity to ask Quillen about that 1943 escape. Quillen, a bank robber and kidnapper imprisoned on the island for ten years from 1942 to 1952, knew James Boarman.