Original publish date: March 19, 2020

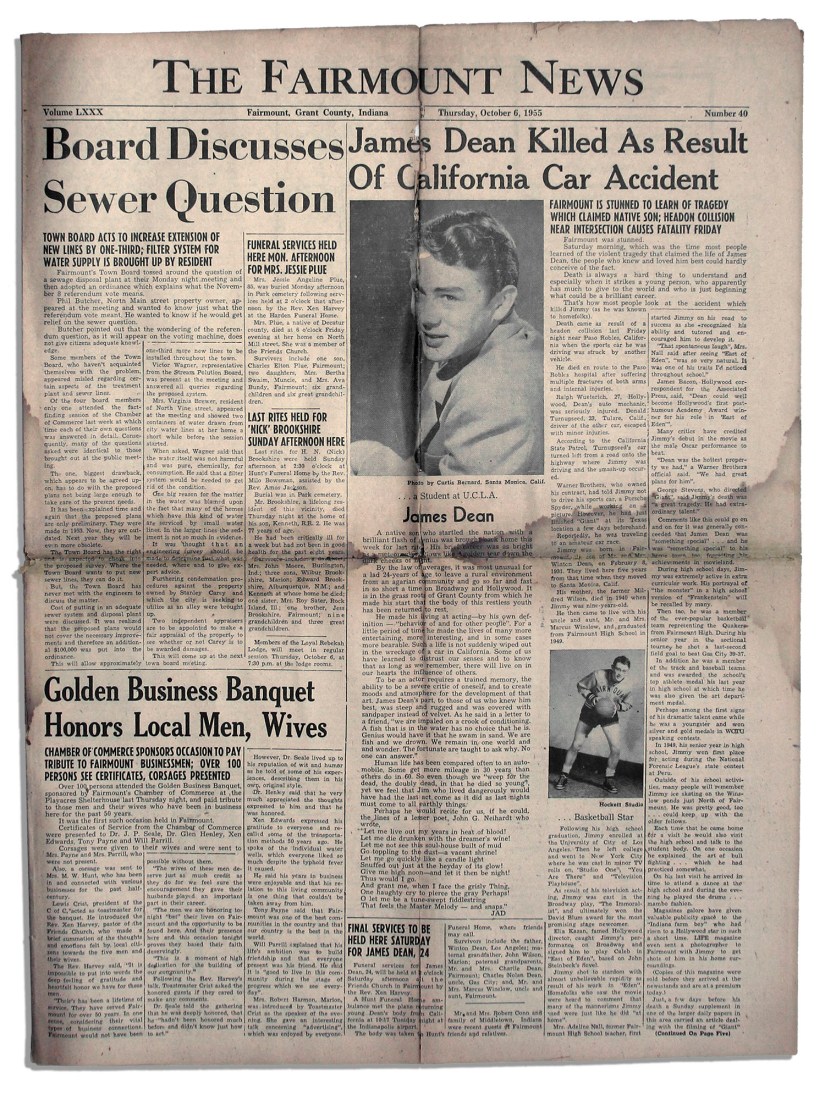

“Live fast, die young and leave a good looking corpse.” James Dean was the epitome of that 1949 quote penned by pioneering Chicago African American author Willard Motley. Dean died in a car crash nearly 65 years ago (September 30, 1955) but he remains a fixture on the pop culture landscape as the gold standard of cool. If you need proof of that assessment, go and visit his grave in Fairmount, Indiana. There you will see the lipstick spotted grave marker covered by more kisses than the yard of bricks at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

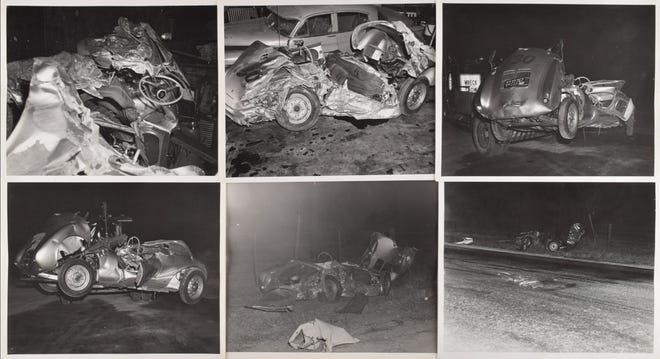

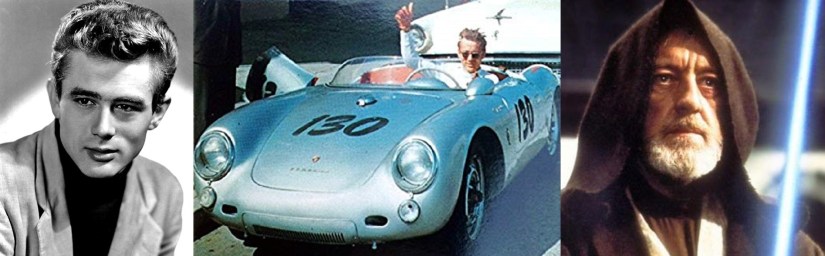

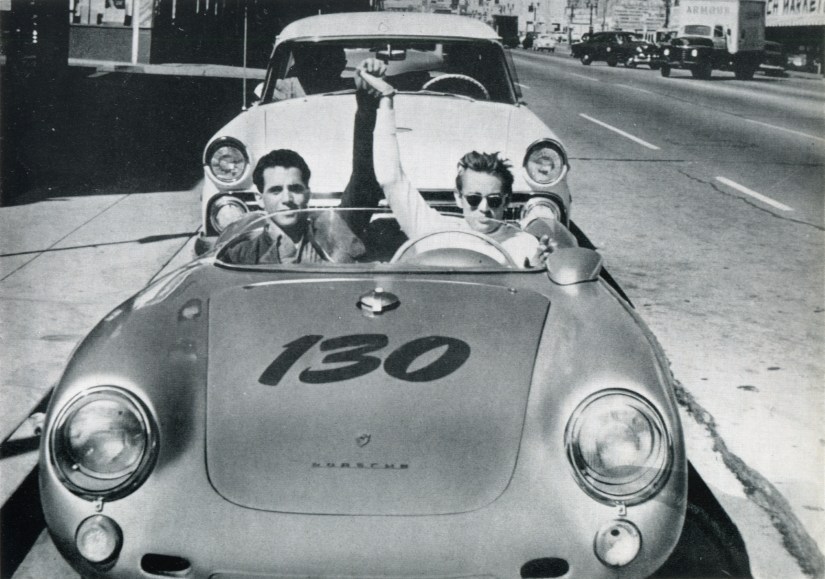

James Dean’s aluminium-bodied Porsche was launched into the air, torn and crushed. But that was not the end of the car’s story. The “curse” of James Dean’s car has become a part of America’s cultural mythology. Some claim that the source of that “curse” was none other than iconic Pop Culture car creator known as the “King of the Kustomizers”, George Barris. It was Barris who created the Batmobile, the Beverly Hillbillies truck, the Munster Koach and Grandpa Munster’s “Drag-U-La” casket car used in the 1960s TV series. It was Barris who painted the number 130 on the doors, front hood and rear trunk of Dean’s Posche Spyder. It was Barris who also stenciled the name “Little Bastard” on the back of the car. And it was Barris who eventually came to own the deathcar.

James Dean’s aluminium-bodied Porsche was launched into the air, torn and crushed. But that was not the end of the car’s story. The “curse” of James Dean’s car has become a part of America’s cultural mythology. Some claim that the source of that “curse” was none other than iconic Pop Culture car creator known as the “King of the Kustomizers”, George Barris. It was Barris who created the Batmobile, the Beverly Hillbillies truck, the Munster Koach and Grandpa Munster’s “Drag-U-La” casket car used in the 1960s TV series. It was Barris who painted the number 130 on the doors, front hood and rear trunk of Dean’s Posche Spyder. It was Barris who also stenciled the name “Little Bastard” on the back of the car. And it was Barris who eventually came to own the deathcar.

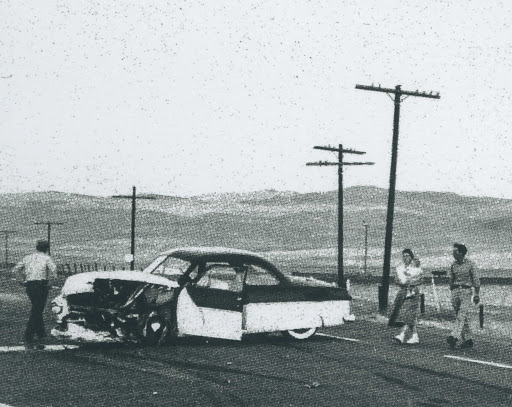

The wrecked Spyder was declared a total loss by the insurance company, which paid Dean’s father, Winton, the fair market value as a settlement. The insurance company, through a salvage yard in Burbank, sold the Spyder to a Dr. William F. Eschrich, a driver who had competed against Dean in his own sports car at three races in 1955. Dr. Eschrich installed Dean’s Porsche 4-cam engine in his Lotus IX race car chassis. Eschrich then raced the Porsche-powered Lotus, which he called a “Potus”, at seven California Sports Car Club events during 1956. At the Pomona Sports Car Races on October 21, 1956, Eschrich, driving this car, was involved in a minor scrape with another driver. In that same race, a Dr. McHenry was killed when his race car went out of control and struck a tree. Dr. Eschrich had loaned Dr. McHenry the transmission and several other parts from James Dean’s deathcar.

After Dr. Eschrich striped the car of it’s engine and any other salvageable racing components, he evidently sold the Spyder’s mangled chassis to Barris. It is not known exactly how Barris knew Eschrich, but in late-1956, Barris announced that he would rebuild the Porsche. However, as the wrecked chassis had no remaining integral strength, a rebuild proved to be a Herculean task, even for a wizard like Barris. Barris welded aluminum sheet metal over the caved-in left front fender and cockpit. He then beat on the aluminum panels with a 2×4 to try to mimic collision damage. So, likely to protect his investment and reputation, Barris promoted the “curse” by placing the wreck on public display.

After Dr. Eschrich striped the car of it’s engine and any other salvageable racing components, he evidently sold the Spyder’s mangled chassis to Barris. It is not known exactly how Barris knew Eschrich, but in late-1956, Barris announced that he would rebuild the Porsche. However, as the wrecked chassis had no remaining integral strength, a rebuild proved to be a Herculean task, even for a wizard like Barris. Barris welded aluminum sheet metal over the caved-in left front fender and cockpit. He then beat on the aluminum panels with a 2×4 to try to mimic collision damage. So, likely to protect his investment and reputation, Barris promoted the “curse” by placing the wreck on public display.

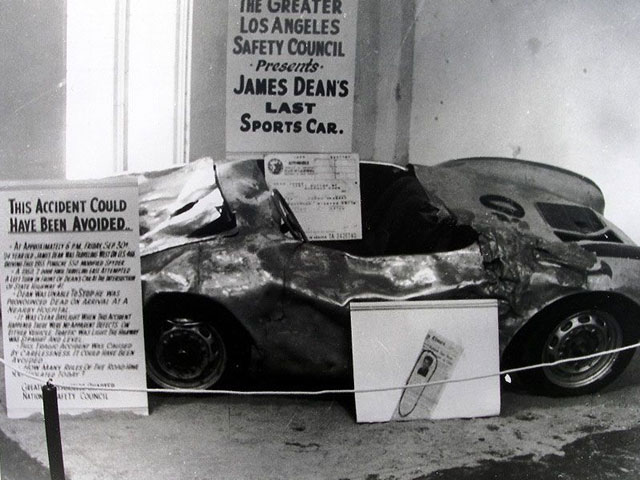

First, Barris loaned the car out to the Los Angeles chapter of the National Safety Council for a local custom car show in 1956. The gruesome display was promoted as: “James Dean’s Last Sports Car”. From 1957 to 1959, the exhibit toured the country in various custom car shows, movie theatres, bowling alleys, and highway safety displays throughout California. It even made an appearance at Indianapolis Raceway Park during the NHRA Drag Racing Championship track’s grand opening in 1960. According to Barris, during those years 1956 to 1960, a mysterious series of accidents, not all of them car crashes, occurred involving the car resulting in serious injuries to spectators and even a truck driver’s death.

First, Barris loaned the car out to the Los Angeles chapter of the National Safety Council for a local custom car show in 1956. The gruesome display was promoted as: “James Dean’s Last Sports Car”. From 1957 to 1959, the exhibit toured the country in various custom car shows, movie theatres, bowling alleys, and highway safety displays throughout California. It even made an appearance at Indianapolis Raceway Park during the NHRA Drag Racing Championship track’s grand opening in 1960. According to Barris, during those years 1956 to 1960, a mysterious series of accidents, not all of them car crashes, occurred involving the car resulting in serious injuries to spectators and even a truck driver’s death.

A few of those stories can be corroborated. A March 12, 1959 wire service story reported that the deathcar, temporarily stored in a garage at 3158 Hamilton Avenue in Fresno, caught fire “awaiting display as a safety exhibit in a coming sports and custom automobile show”. The Fresno Bee followed up with a newspaper story exactly two months later, stating that the “fire occurred on the night of March 11 and only slight damage occurred to the Spyder without any damage to other cars or property in the garage. No one was injured. The cause of the fire is unknown. It burned two tires and scorched the paint on the vehicle.” Barris claimed that the deathcar mysteriously disappeared in 1960 while returning from a traffic safety exhibit in Florida in a sealed railroad boxcar. When the train arrived in Los Angeles, Barris said he signed the manifest and verified that the seal was intact—but the boxcar was empty. Barris offered $1,000,000 to anyone who could produce the remains of the deathcar, but no one ever came forward to claim the prize.

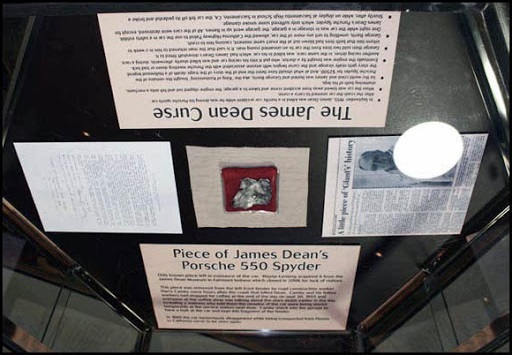

Although the legendary car has disappeared, Historic Auto Attractions in Roscoe, Illinois, claims to have an original piece of Dean’s Spyder on display. It is a small chunk of aluminum, a few square inches in size, that was allegedly pried off and stolen from an area near the broken windscreen while the Spyder was being stored in the Cholame Garage after the crash. Also on display in the museum are an assortment of Abraham Lincoln relics (a lock of his hair, the handles from his coffin, various bloodstained cloth and one of the coins purportedly placed on the dead President’s eyes) as well as the Bonnie & Clyde, Flintstones, Back to the Future Movie cars and George Barris’ Batmobile. In 2005, for the 50th anniversary of Dean’s death, the Volo Auto Museum in Volo, Illinois, announced they were displaying what was purported to be the passenger door of the “Little Bastard”.

The 4-Cam Porsche engine (#90059), along with the original California Owner’s Registration (a.k.a. CA Pink Slip) listing the engine number, is still in the possession of the family of the late Dr. Eschrich. The Porsche’s transaxle assembly (#10046), is currently owned by Porsche collector and restorer Jack Styles in Massachusetts. But, to date, neither of Dean’s Porsches have been located. In his 1974 book “Cars of the Stars” George Barris first wrote about the curse and the numerous incidents involving fatal accidents and other serious injuries, but other than the few minor mishaps reported here, researchers have found no evidence to support most of Barris’ claims. Regardless, the story of the curse has certainly failed to diminish the James Dean legend.

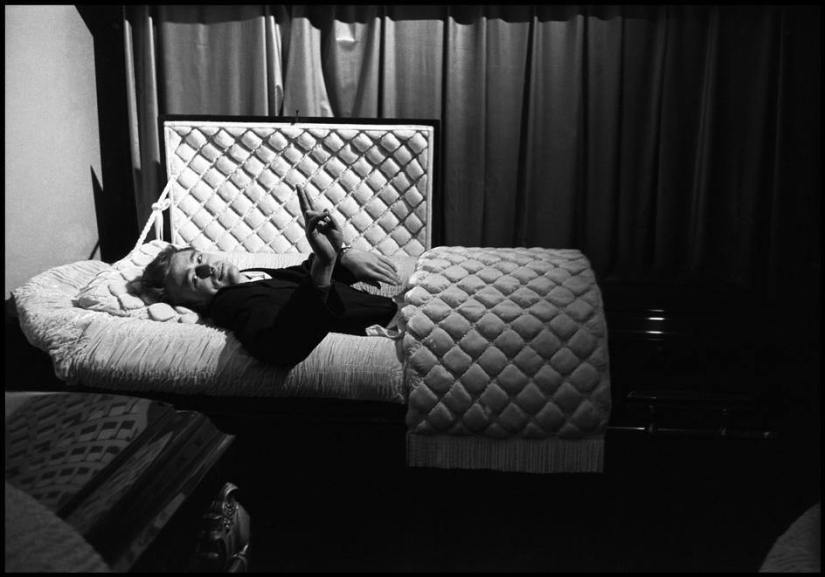

Like many a Hoosier youth, I too had my “James Dean phase”. Some twenty years ago, my wife Rhonda and I took a trip up to Fairmount to visit James Dean country. We were toured around the community by a couple of older gentlemen who graciously pointed out spots the young actor frequented including the family farm, Dean’s old high school, a few of the old stores Dean used to frequent, the cemetery and the funeral home where Dean was prepared for burial. One of the men mentioned, “He had a closed-casket funeral to conceal his severe injuries from his hometown friends and family.” These men had been underclassmen at Fairmount high school and relayed stories of encounters with Dean from their school days. They remarked that when the young method actor returned to Fairmount after making a Pepsi commercial and a bit part on TV, Dean attended a high school dance. “We didn’t like him because he had all of the girls in the room fawning all over him and we couldn’t get a dance.” they said. “We didn’t see him as a big shot from Hollywood, we saw him as a guy trying to steal our dates.”

Like many a Hoosier youth, I too had my “James Dean phase”. Some twenty years ago, my wife Rhonda and I took a trip up to Fairmount to visit James Dean country. We were toured around the community by a couple of older gentlemen who graciously pointed out spots the young actor frequented including the family farm, Dean’s old high school, a few of the old stores Dean used to frequent, the cemetery and the funeral home where Dean was prepared for burial. One of the men mentioned, “He had a closed-casket funeral to conceal his severe injuries from his hometown friends and family.” These men had been underclassmen at Fairmount high school and relayed stories of encounters with Dean from their school days. They remarked that when the young method actor returned to Fairmount after making a Pepsi commercial and a bit part on TV, Dean attended a high school dance. “We didn’t like him because he had all of the girls in the room fawning all over him and we couldn’t get a dance.” they said. “We didn’t see him as a big shot from Hollywood, we saw him as a guy trying to steal our dates.”

During our 10th wedding anniversary trip to California in 1999, Rhonda and I drove from San Francisco to Hollywood. Part of the way on scenic Highway 101 (which I highly recommend should you ever find yourself out that way) and part of the way retracing James Dean’s final drive. The best way you could envision the scene while sitting here in Indiana in the dead of winter would be for you to make a peace sign with the index and middle fingers of your right hand. Hold your arm straight out. The crash happened where your fingers meet, with the Porsche coming toward you on your middle finger and the Ford traveling up your forearm toward your index finger in the opposite direction. Imagine Turnupseed’s car bearing left and swerving onto your index finger precisely at the same time as Dean’s car passes the same spot. Got it?

Driving along that long two-lane stretch of Central California highway, it’s easy to imagine what James Dean’s last hour was like even though much of today’s road isn’t the same one James Dean traveled on. The route was upgraded and moved slightly north in the 1960s. However, parts of the original can still be found. As you drive west on the last mile to the crash site and look off to your left and you can still see what’s left of the original two-lane road. If you pull off to the side of the road, it’s still possible to walk on part of the crumbling pavement, with weeds sprouting in the middle, and imagine that little silver Porsche speeding past.

Driving along that long two-lane stretch of Central California highway, it’s easy to imagine what James Dean’s last hour was like even though much of today’s road isn’t the same one James Dean traveled on. The route was upgraded and moved slightly north in the 1960s. However, parts of the original can still be found. As you drive west on the last mile to the crash site and look off to your left and you can still see what’s left of the original two-lane road. If you pull off to the side of the road, it’s still possible to walk on part of the crumbling pavement, with weeds sprouting in the middle, and imagine that little silver Porsche speeding past.

From this vantage point, it’s also easy to understand how Donald Turnupseed didn’t see the tiny silver sports car as it approached from the foot of the Polonio Pass. The road shimmers along this route, making it hard to tell where the road ends and the horizon begins. Cars appear and disappear in vaporous waves of prismic light like an optical illusion as light reflects off the road surface. Today, the intersection has been widened and there’s a left-turn lane to access Highway 41 requiring a stop and a 90-degree turn. A road sign rises from the median between the converging lanes ominously proclaiming it as “James Dean Memorial Junction”. The two lanes have remained virtually unchanged since then, while the population of the southern San Joaquin Valley has grown 120% since the crash. Headlight use is mandatory along the 58-mile route, from Lost Hills off Interstate 5 to past Paso Robles to the west. Today, the spot where James Dean died is known as “Blood Alley” due to the number of fatal crashes, mainly head-on collisions, that still occur there among the high volume of commuters, truck drivers, and tourists today. Highway officials report that 42 deaths occurred on the road during the 45 years after James Dean’s passing. Another 38 were killed from 2000 to 2010.

Parking and walking over to the spot where James Dean died is a dangerous exercise on this remote, but very busy highway. Cars and trucks speed by in both directions and anything short of a cautious drive by is not recommended. Where Highway 41 merges into Highway 46, on a barbed-wire fence off the westbound lane, is a small memorial signifying the spot where Dean’s Porsche skidded to a stop. There is a small barren patch dotted with tufts of grass. It can easily be missed unless you know it’s there. It sort of blends in to the surrounding nothingness except for the shadows of footprints and mementos left by fans from all over the world. In September 2015, The Hollywood Reporter noted that visitors to the crash site leave an assortment of tributes, including pictures, alcohol and women’s underwear. However, contrary to popular belief, this is not the actual intersection where the accident occurred. The accident scene is approximately 100 feet to the south of the current intersection, where the road used to be. Seems that retrospectively, Dean’s death, like his life, can easily get lost in the legend. One thing is certain though, the crash that killed the rising Hoosier movie star succeeded in cementing his status as a legend.

Macabre Images of James Dean clowning in the Fairmount Funeral Home.

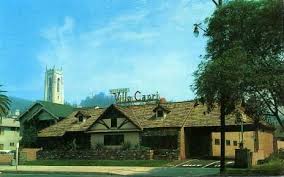

Guinness and Moss followed Dean to the restaurant, but before they reached the door, Dean stopped and said, “I’d like to show you something.” Years later, Guinness recalled “There in the courtyard of this little restaurant was this little silver thing, very smart, all done up in cellophane with a bunch of roses tied to its bonnet.” The young method actor told his new British star, “It’s just been delivered,” said Dean “I haven’t even been in it at all.” Guinness thought the car looked “sinister”. “How fast is it?” he asked. “She’ll do a hundred and fifty,” replied Dean.

Guinness and Moss followed Dean to the restaurant, but before they reached the door, Dean stopped and said, “I’d like to show you something.” Years later, Guinness recalled “There in the courtyard of this little restaurant was this little silver thing, very smart, all done up in cellophane with a bunch of roses tied to its bonnet.” The young method actor told his new British star, “It’s just been delivered,” said Dean “I haven’t even been in it at all.” Guinness thought the car looked “sinister”. “How fast is it?” he asked. “She’ll do a hundred and fifty,” replied Dean. At 3:30 p.m., Dean was stopped by California Highway Patrolman O.V. Hunter at Mettler Station on Wheeler Ridge, just south of Bakersfield, for driving 65 mph in a 55 mph zone. Hickman, following the Spyder in Dean’s Ford “woodie” station wagon pulling the trailer, was also ticketed for driving 20 mph over the limit, as the speed limit for all vehicles towing a trailer was 45 mph. After receiving the citations, Dean and Hickman turned left onto SR 166 / 33 to bypass Bakersfield’s congested downtown district. This bypass became known as “the racer’s road”, a popular short-cut for sports car drivers going to Salinas. The racer’s road went directly to Blackwells Corner at U.S. Route 466 (later SR 46). Around 5:00 p.m., Dean stopped at Blackwells Corner for “apples and Coca-Cola” and met up briefly with fellow racers Lance Reventlow and Bruce Kessler, who were also on their way to Salinas in Reventlow’s Mercedes-Benz 300 SL coupe. As Reventlow and Kessler were leaving, they all agreed to meet for dinner that night in Paso Robles.

At 3:30 p.m., Dean was stopped by California Highway Patrolman O.V. Hunter at Mettler Station on Wheeler Ridge, just south of Bakersfield, for driving 65 mph in a 55 mph zone. Hickman, following the Spyder in Dean’s Ford “woodie” station wagon pulling the trailer, was also ticketed for driving 20 mph over the limit, as the speed limit for all vehicles towing a trailer was 45 mph. After receiving the citations, Dean and Hickman turned left onto SR 166 / 33 to bypass Bakersfield’s congested downtown district. This bypass became known as “the racer’s road”, a popular short-cut for sports car drivers going to Salinas. The racer’s road went directly to Blackwells Corner at U.S. Route 466 (later SR 46). Around 5:00 p.m., Dean stopped at Blackwells Corner for “apples and Coca-Cola” and met up briefly with fellow racers Lance Reventlow and Bruce Kessler, who were also on their way to Salinas in Reventlow’s Mercedes-Benz 300 SL coupe. As Reventlow and Kessler were leaving, they all agreed to meet for dinner that night in Paso Robles.

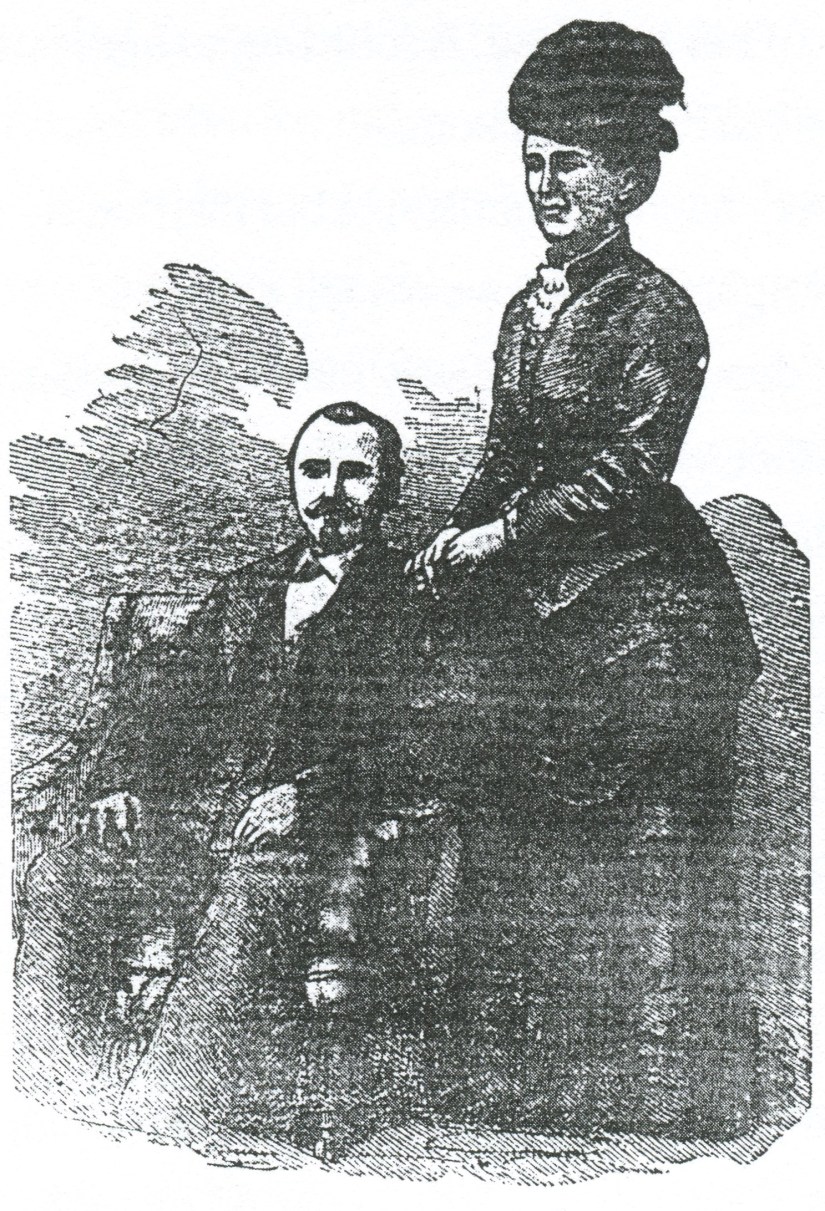

If he was fearful, Joseph Brown did not show it as he sat down for what would be his last meal. At 5:30 PM, Mary Brown sent her two older children to the Smith’s, neighbors whose home was frequently visited by Wade, the children and Mary Brown. Mary instructed the children that she would come to get them after dinner and that Wade would play fiddle that evening to entertain at the Smith home. During the course of the evening, Wade asked Brown to borrow his buggy. He stated that he wanted to sell a horse to Irvington’s Dr. long. Brown agreed. As dinner ended, Brown went into the front yard to work on an ax handle. Wade was hitching the horse to the buggy.

If he was fearful, Joseph Brown did not show it as he sat down for what would be his last meal. At 5:30 PM, Mary Brown sent her two older children to the Smith’s, neighbors whose home was frequently visited by Wade, the children and Mary Brown. Mary instructed the children that she would come to get them after dinner and that Wade would play fiddle that evening to entertain at the Smith home. During the course of the evening, Wade asked Brown to borrow his buggy. He stated that he wanted to sell a horse to Irvington’s Dr. long. Brown agreed. As dinner ended, Brown went into the front yard to work on an ax handle. Wade was hitching the horse to the buggy. The investigation by Coroner George Wishard, namesake of today’s Wishard Hospital, was thorough and damning to Wade. During his investigation at the Brown farm, Wishard “found a board, probably a small kneading tray, hidden away under the shed… Which is bespattered with blood.” Signs of a violent struggle and blood were found in the yard. The mountain of evidence was building against Wade. But did he act alone? Or was “Bloody Mary” Brown, as one of the contemporary newspapers dubbed her, more involved than she claimed?

The investigation by Coroner George Wishard, namesake of today’s Wishard Hospital, was thorough and damning to Wade. During his investigation at the Brown farm, Wishard “found a board, probably a small kneading tray, hidden away under the shed… Which is bespattered with blood.” Signs of a violent struggle and blood were found in the yard. The mountain of evidence was building against Wade. But did he act alone? Or was “Bloody Mary” Brown, as one of the contemporary newspapers dubbed her, more involved than she claimed?

One of those “must see” old timey casinos is located about 30 miles southwest of the Vegas strip in a desert town called Primm, Nevada not far from the California border. Known as “Whiskey Pete’s”, the casino covers 35,000 square feet, has 777 rooms, a large swimming pool, gift shop and four restaurants. The casino is named after gas station owner Pete MacIntyre. “Whiskey Pete” had a difficult time making ends meet selling gas, so he resorted to bootlegging and an idea was born. When Whiskey Pete died in 1933, he was secretly buried standing up with a bottle of whiskey in his hands so he could watch over the area. Decades later, his unmarked grave was accidentally exhumed by workers building a connecting bridge from Whiskey Pete’s to Buffalo Bill’s (on the other side of I-15). According to legend, the body was reburied in one of the caves where Pete once cooked up his moonshine.

One of those “must see” old timey casinos is located about 30 miles southwest of the Vegas strip in a desert town called Primm, Nevada not far from the California border. Known as “Whiskey Pete’s”, the casino covers 35,000 square feet, has 777 rooms, a large swimming pool, gift shop and four restaurants. The casino is named after gas station owner Pete MacIntyre. “Whiskey Pete” had a difficult time making ends meet selling gas, so he resorted to bootlegging and an idea was born. When Whiskey Pete died in 1933, he was secretly buried standing up with a bottle of whiskey in his hands so he could watch over the area. Decades later, his unmarked grave was accidentally exhumed by workers building a connecting bridge from Whiskey Pete’s to Buffalo Bill’s (on the other side of I-15). According to legend, the body was reburied in one of the caves where Pete once cooked up his moonshine. Oh, I forgot to mention that Whiskey Pete’s is also home to the Bonnie and Clyde death car. As detailed in part III of this series, the car has had a long strange trip to Primm. The bullet-ridden car toured carnivals, amusement parks, flea markets, and state fairs for decades before being permanently parked on the plush carpet between the main cashier cage and a lifesize caged effigy of Whiskey Pete himself. According to the “Roadside America” website, “For a time it was in the Museum of Antique Autos in Princeton, Massachusetts, then in the 1970s it was at a Nevada race track where people could sit in it for a dollar. A decade later it was in a Las Vegas car museum; a decade after that it was in a casino near the California / Nevada state line. It was then moved to a different casino on the other side of the freeway, then it went on tour to other casinos in Iowa, Missouri, and northern Nevada.

Oh, I forgot to mention that Whiskey Pete’s is also home to the Bonnie and Clyde death car. As detailed in part III of this series, the car has had a long strange trip to Primm. The bullet-ridden car toured carnivals, amusement parks, flea markets, and state fairs for decades before being permanently parked on the plush carpet between the main cashier cage and a lifesize caged effigy of Whiskey Pete himself. According to the “Roadside America” website, “For a time it was in the Museum of Antique Autos in Princeton, Massachusetts, then in the 1970s it was at a Nevada race track where people could sit in it for a dollar. A decade later it was in a Las Vegas car museum; a decade after that it was in a casino near the California / Nevada state line. It was then moved to a different casino on the other side of the freeway, then it went on tour to other casinos in Iowa, Missouri, and northern Nevada.  Complicating matters was the existence of at least a half-dozen fake Death Cars and the Death Car from the 1967 Bonnie and Clyde movie (which was in Louisiana and then Washington, DC, but now is in Tennessee).” Just in case of any remaining confusion, the Primm car is accompanied by a bullet riddled sign reading: “Yes, this is the original, authentic Bonnie and Clyde death car” (in all caps for emphasis).

Complicating matters was the existence of at least a half-dozen fake Death Cars and the Death Car from the 1967 Bonnie and Clyde movie (which was in Louisiana and then Washington, DC, but now is in Tennessee).” Just in case of any remaining confusion, the Primm car is accompanied by a bullet riddled sign reading: “Yes, this is the original, authentic Bonnie and Clyde death car” (in all caps for emphasis).

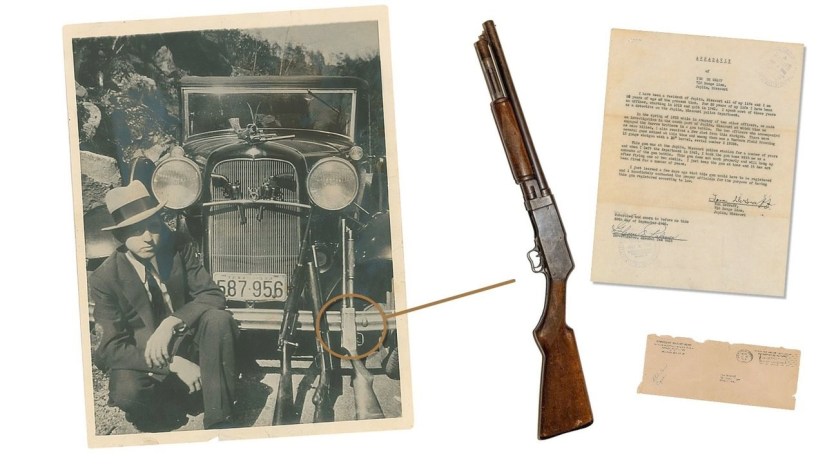

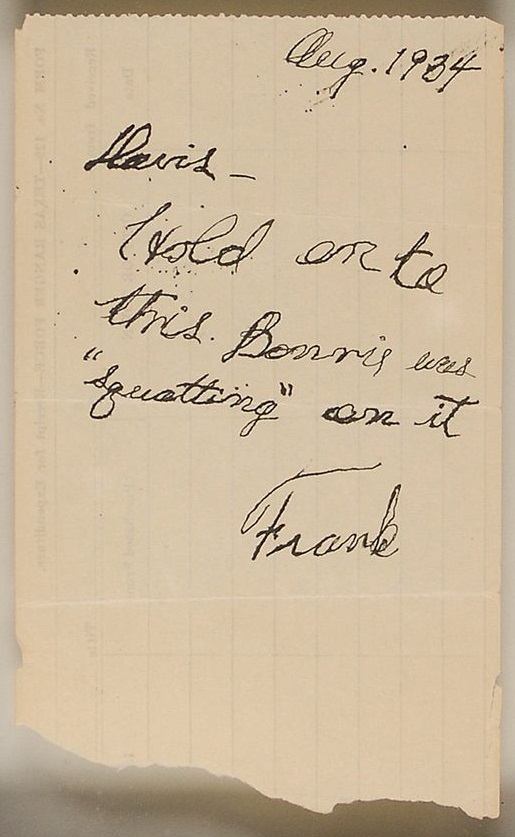

The walls surrounding the death car are festooned with authentic newspapers detailing the outlaw lover’s demise and letters vouching to the vehicle’s authenticity. Cases contain other Bonnie and Clyde relics like a belt given by Clyde to his sister and classic candid photos of the star-crossed lovers and their families.

The walls surrounding the death car are festooned with authentic newspapers detailing the outlaw lover’s demise and letters vouching to the vehicle’s authenticity. Cases contain other Bonnie and Clyde relics like a belt given by Clyde to his sister and classic candid photos of the star-crossed lovers and their families. A movie, obviously created many years ago, recreates the event using newsreel footage, landscape photography and contemporary interviews with family members and eyewitnesses. Here, it is revealed that the shirt was found, decades after the outlaw’s death, secreted away in a sealed metal box along with Clyde’s hat. The film itself has become a piece of Americana and the images of Bonnie’s torn and tattered body left twitching in the car, resting silently mere yards away, are equally breathtaking. Nearby, although not nearly as shocking as the Bonnie and Clyde death car, another bullet-scarred automobile is on display. This one first belonged to gangster Dutch Schultz and later, Al Capone. Signs around the car proclaim that the doors are filled with lead and, judging by the pockmarks of the bullets denting the exterior, it is true. Although, like every casino, Whiskey Pete’s job remains separating gamblers from their money, both cars are on display 24 hours a day for free.

A movie, obviously created many years ago, recreates the event using newsreel footage, landscape photography and contemporary interviews with family members and eyewitnesses. Here, it is revealed that the shirt was found, decades after the outlaw’s death, secreted away in a sealed metal box along with Clyde’s hat. The film itself has become a piece of Americana and the images of Bonnie’s torn and tattered body left twitching in the car, resting silently mere yards away, are equally breathtaking. Nearby, although not nearly as shocking as the Bonnie and Clyde death car, another bullet-scarred automobile is on display. This one first belonged to gangster Dutch Schultz and later, Al Capone. Signs around the car proclaim that the doors are filled with lead and, judging by the pockmarks of the bullets denting the exterior, it is true. Although, like every casino, Whiskey Pete’s job remains separating gamblers from their money, both cars are on display 24 hours a day for free. The interior of the Pioneer Saloon remains unchanged. It is easy to imagine Gone with the Wind star Gable drowning his sorrows at a rickety table or bracing himself against the cowboy bar and it’s brass boot rail. Ask and the bartender will point out the cigarette burn holes in the bar caused by Gable when he passed out from a mixture of grief and alcohol during his somber vigil. The tin ceiling remains as do the ancient celing fans (it gets HOT in the desert) and the walls are peppered with bullet holes left by cowboys who rode off into the sunset generations ago. The bar’s backroom is a shrine to the Lombard / Gable tragedy but sadly most of the relics on display there are modern photocopies and recreations. Locals claim that Carole Lombard’s ghost haunts the saloon in a desperate attempt to contact her grieving husband. The saloon is also reportedly haunted by the ghost of an old “Miner 49er” who appears drinking alone at the far end of the bar before vanishing into thin air. Millennials flock to the bar as the birthplace of the game “Fallout: New Vegas” which also has a small shrine located there.

The interior of the Pioneer Saloon remains unchanged. It is easy to imagine Gone with the Wind star Gable drowning his sorrows at a rickety table or bracing himself against the cowboy bar and it’s brass boot rail. Ask and the bartender will point out the cigarette burn holes in the bar caused by Gable when he passed out from a mixture of grief and alcohol during his somber vigil. The tin ceiling remains as do the ancient celing fans (it gets HOT in the desert) and the walls are peppered with bullet holes left by cowboys who rode off into the sunset generations ago. The bar’s backroom is a shrine to the Lombard / Gable tragedy but sadly most of the relics on display there are modern photocopies and recreations. Locals claim that Carole Lombard’s ghost haunts the saloon in a desperate attempt to contact her grieving husband. The saloon is also reportedly haunted by the ghost of an old “Miner 49er” who appears drinking alone at the far end of the bar before vanishing into thin air. Millennials flock to the bar as the birthplace of the game “Fallout: New Vegas” which also has a small shrine located there.

During the Great Depression, some viewed the duo as near folk heroes, like Robin Hood and Maid Marian. And, although Hoosier outlaw John Dillinger reportedly once told a reporter that Bonnie and Clyde were “a couple of punks”, he and his fellow gang member Pretty Boy Floyd reportedly sent flowers to their funeral homes. The Barrow gang killed a total of 13 people, including nine police officers. They finally met their match on May 23, 1934, when six police officers ambushed them and shot some 130 rounds into the car. Dillinger outlasted Bonnie and Clyde by about two months – he met his maker on July 22, 1934. Truth is, proceeds from auctions of items associated with these outlaws over the past two decades (which number in the millions of dollars) far outdistance the proceeds of all of their robberies combined.

During the Great Depression, some viewed the duo as near folk heroes, like Robin Hood and Maid Marian. And, although Hoosier outlaw John Dillinger reportedly once told a reporter that Bonnie and Clyde were “a couple of punks”, he and his fellow gang member Pretty Boy Floyd reportedly sent flowers to their funeral homes. The Barrow gang killed a total of 13 people, including nine police officers. They finally met their match on May 23, 1934, when six police officers ambushed them and shot some 130 rounds into the car. Dillinger outlasted Bonnie and Clyde by about two months – he met his maker on July 22, 1934. Truth is, proceeds from auctions of items associated with these outlaws over the past two decades (which number in the millions of dollars) far outdistance the proceeds of all of their robberies combined. For my part, when we told our 25-year-old son about our anniversary trip to Las Vegas, he remained nonplussed by saying, “I would only want to go out there to see a town called Primm.” To which we said “been there, done that.” His reply, “I’d also like to go to a little town called Good Springs.” We answered, “Been there too.” He concluded by saying he’d like to see an old dive bar named the “Pioneer Saloon.” He was shocked when we said we went there too. Of course, the reason he wants to venture out there is video game related, not history related. Nonetheless, he was chagrined by our answers. I guess we old folks aren’t so square after all.

For my part, when we told our 25-year-old son about our anniversary trip to Las Vegas, he remained nonplussed by saying, “I would only want to go out there to see a town called Primm.” To which we said “been there, done that.” His reply, “I’d also like to go to a little town called Good Springs.” We answered, “Been there too.” He concluded by saying he’d like to see an old dive bar named the “Pioneer Saloon.” He was shocked when we said we went there too. Of course, the reason he wants to venture out there is video game related, not history related. Nonetheless, he was chagrined by our answers. I guess we old folks aren’t so square after all.

She called the police and reported the car as stolen. According to the police report, shortly after one o’clock, neighbors saw a man and a woman circling the block in a Plymouth coupe. Later the mystery couple returned, this time with a man riding on the right running board. He jumped off, climbed into the Warren’s car, started it, backed out of the driveway, and sped away. The Warrens wouldn’t see their new Ford for three months.

She called the police and reported the car as stolen. According to the police report, shortly after one o’clock, neighbors saw a man and a woman circling the block in a Plymouth coupe. Later the mystery couple returned, this time with a man riding on the right running board. He jumped off, climbed into the Warren’s car, started it, backed out of the driveway, and sped away. The Warrens wouldn’t see their new Ford for three months.

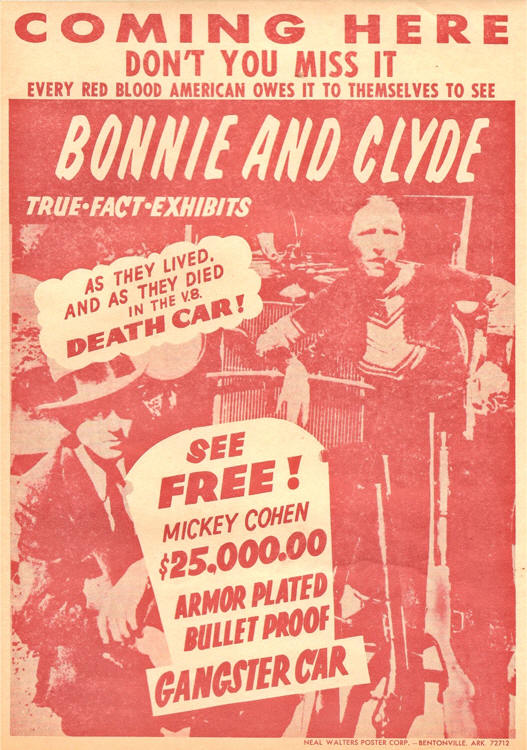

Ruth then rented the death car to carnival operator Charles Stanley, who exhibited it on the Hennies Brothers Midways in his 1939 crime show. Stanley displayed the car outside of his tent and charged admission to see the film of the actual ambush on the inside. Eventually, multiple bullet-riddled 1934 Ford Fordor sedans began appearing on the county fair and carnival circuit over the next few years, all claiming to be the actual death car. The various owners sometimes vigorously defended their claims, too, casting doubt on the authenticity of the real death car. Aside from the damage to historical accuracy, the frauds cut into the revenue generated by Ruth Warren as the death car toured the country.

Ruth then rented the death car to carnival operator Charles Stanley, who exhibited it on the Hennies Brothers Midways in his 1939 crime show. Stanley displayed the car outside of his tent and charged admission to see the film of the actual ambush on the inside. Eventually, multiple bullet-riddled 1934 Ford Fordor sedans began appearing on the county fair and carnival circuit over the next few years, all claiming to be the actual death car. The various owners sometimes vigorously defended their claims, too, casting doubt on the authenticity of the real death car. Aside from the damage to historical accuracy, the frauds cut into the revenue generated by Ruth Warren as the death car toured the country. After Ruth divorced her husband Jesse, she kept the title to the car and sold it to Stanley for $3,500.The car was then exhibited at Coney Island amusement park in Cincinnati from 1940-1960. After World War II, memories faded and interest waned in the “Public Enemies” Era, pushing the car further-and-further into obscurity. In a 1960 issue of Billboard magazine, Stanley offered the Bonnie and Clyde Death Car for sale. Ted Toddy purchased the car in 1960 for $14,500. The car then sat in a warehouse for years until the popularity of the 1967 movie “Bonnie & Clyde” brought it out of retirement.

After Ruth divorced her husband Jesse, she kept the title to the car and sold it to Stanley for $3,500.The car was then exhibited at Coney Island amusement park in Cincinnati from 1940-1960. After World War II, memories faded and interest waned in the “Public Enemies” Era, pushing the car further-and-further into obscurity. In a 1960 issue of Billboard magazine, Stanley offered the Bonnie and Clyde Death Car for sale. Ted Toddy purchased the car in 1960 for $14,500. The car then sat in a warehouse for years until the popularity of the 1967 movie “Bonnie & Clyde” brought it out of retirement.