Original publish date May 15, 2025.

https://weeklyview.net/2025/05/15/foul-ball/

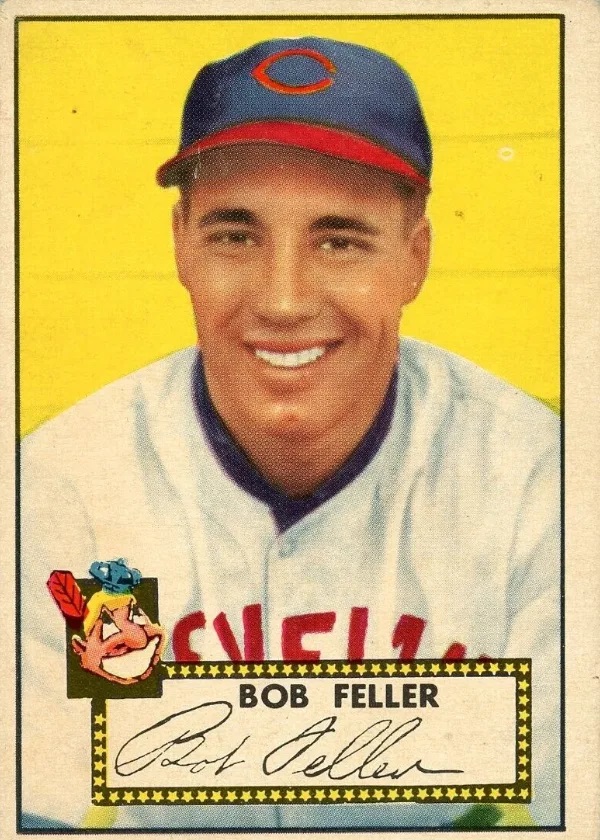

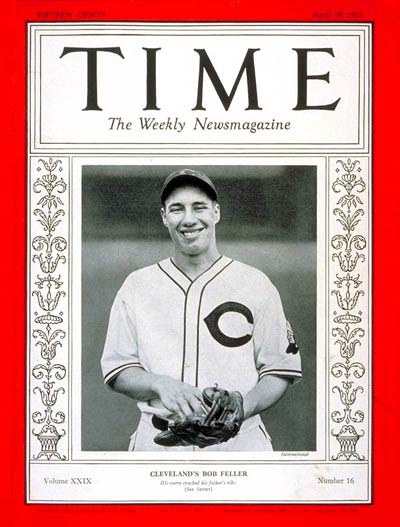

Last week, I ran a story about Cleveland Indians phenom Bob Feller’s pitched foul ball that hit and injured his mother during a game against the White Sox at old Comiskey Park in Chicago. That got me thinking about other foul ball stories and legends I’d heard about. Growing up, I spent a lot of time at old Bush Stadium on 16th Street in Indy. My dad, Robert Eugene Hunter, a 1954 Arsenal Tech grad, had worked there as a kid selling Cracker Jack/popcorn in the stands during the Victory Field years. He recalled with pleasure seeing Babe Ruth in person there and could name his favorites from those great Pittsburgh Pirates farm club teams from the late 1940s/early 1950s. I can’t tell you how many RCA Nights at Bush Stadium he took me to back in the 1970s during the team’s affiliation with the Cincinnati Reds Big Red Machine. During those outings, nothing was more exciting than chasing foul balls.

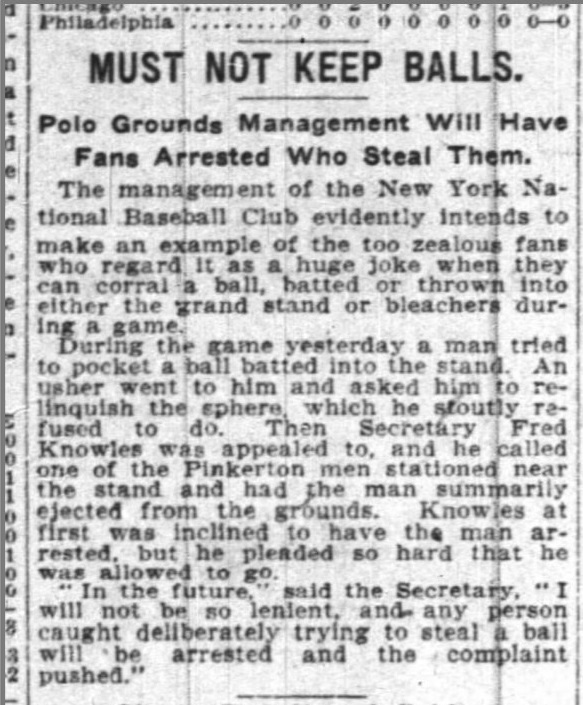

Not all foul balls are fun adventures, though; some are crazy, and others are just plain scary. Growing up, I loved reading about the exploits of those players who played before World War I. Back in those days, baseballs were considered team property and quite expensive. Fans were expected to return any ball hit into the stands (including homeruns), and balls hit out of the stadium were meticulously retrieved. In 1901, the National League rules committee, as a way of cutting costs, suggested fining batters for excessively fouling off pitches. Beginning in 1904, per a newly created league rule, teams posted employees in the stands whose sole job was to retrieve foul balls caught by the fans. Fans had a keen sense of humor, though, and they would often hide them from the “goons” or frustrate the hapless employees by throwing them from row to row. Sometimes, the games of keep-away in the stands were more fun to watch than the ones on the field. But those early WWI stories mostly involved the exploits of the players, not the fans. There were some characters in the league back then. Some of them are long forgotten and some made the Baseball Hall of Fame.

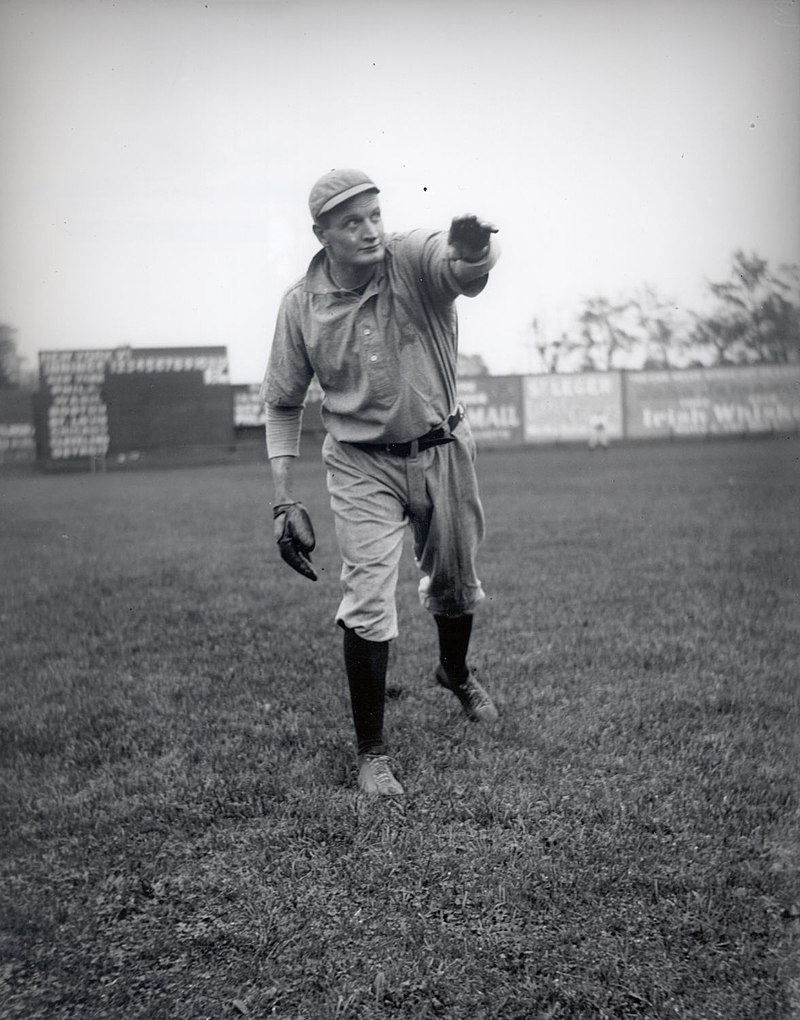

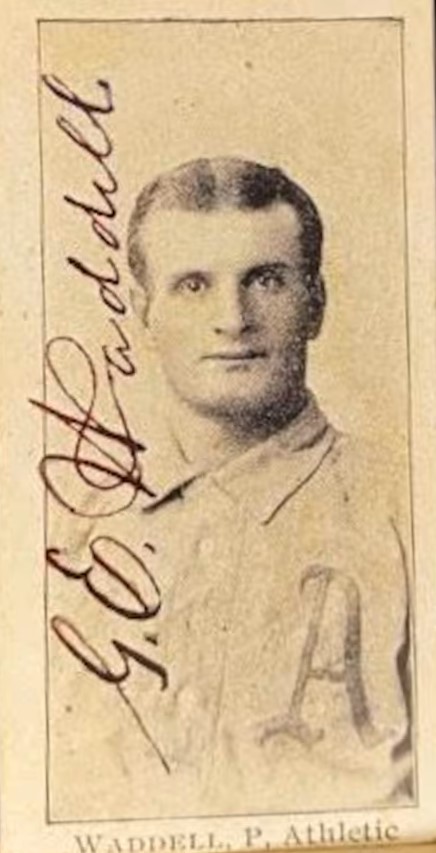

One of my favorite players from that hardball era was a square-jawed eccentric left-handed pitcher from the oil town of Bradford, Pa. named George Edward “Rube” Waddell (1876-1914). Rube played for 5 teams in 13 years. His lifetime 193-143 record, 2,316 strikeouts, and 2.16 ERA landed him in the Hall of Fame. And if there were a hall of fame for flakes in baseball, Rube would have been a first-ballot electee. If a plane flew above the field, Rube would stop in the middle of a game. If Rube heard the siren of a firetruck, he’d drop his glove and chase it. He once left in the middle of a game to go fishing. Opposing fans knew that Rube was easily distracted so they brought puppies to the game and held them up in the stands to throw him off. Rival teams brought puppies into the dugout for the same reason, knowing that Rube would drop his glove and run over to play with them every time. Shiny objects seemed to put Rube in a trance. His eccentric behavior led to constant battles with his managers and scuffles with bad-tempered teammates. Even though he was a standout pitcher, Rube’s foulball stories came off his bat, not out of his hand.

On August 11, 1903, the Philadelphia Athletics were visiting the Red Sox. In the seventh inning, Rube Waddell was at the plate. Waddell lifted a foul ball over the right field bleachers that landed on the roof of a Boston baked bean cannery next door. The ball rolled to a stop and became wedged in the factory’s steam whistle, which caused it to go off. It wasn’t quitting time yet, but the workers abandoned their posts, thinking it was an emergency. The employee exodus caused a giant caldron full of beans to boil over and explode. Suddenly, the ballpark was showered by scalding hot beans. Nine days before, on August 2, another foul ball off the bat of Waddell hit a spectator, supposedly igniting a box of matches in the fan’s pocket and ultimately setting the poor guy’s suit on fire and causing an uproar.

Waddell’s 1903 E107 Card.

Still, a foul ball hit by the aptly named George Burns of the Tigers in 1915 is worth mentioning in the same breath. His “scorching” foul liner struck an unlucky fan in the area of his chest pocket, where he was carrying a box of matches. The ball ignited the matches, and a soda vendor had to come to the rescue, dousing the flaming fan with bubbly to put out the fire.

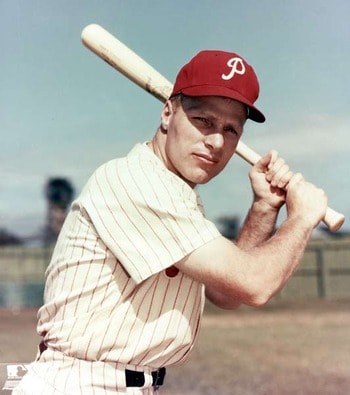

Richie Ashburn figures in many of the best foul ball stories in baseball lore. A contact hitter, Ashburn had the ability to foul off many consecutive pitches till he found one he liked. On one occasion, he fouled off fourteen consecutive pitches against Corky Valentine of the Reds. Another time, he victimized Sal “The Barber” Maglie for “18 or 19″ fouls in one at-bat. ”After a while,” said Ashburn, “he just started laughing. That was the only time I ever saw Maglie laugh on a baseball field.” Ashburn’s bat control was such that one day he asked teammates to pinpoint a particularly offensive heckler seated five or six rows back. The next time up, Ashburn nailed the fan in the chest. On another occasion, Ashburn unintentionally injured a female fan who was the wife of a Philadelphia newspaper sports editor. Play stopped as she was given medical aid. Action resumed as the stretcher wheeled her down the main concourse, and, unbelievably, Ashburn’s next foul hit her again. Thankfully, she escaped with minor injuries.

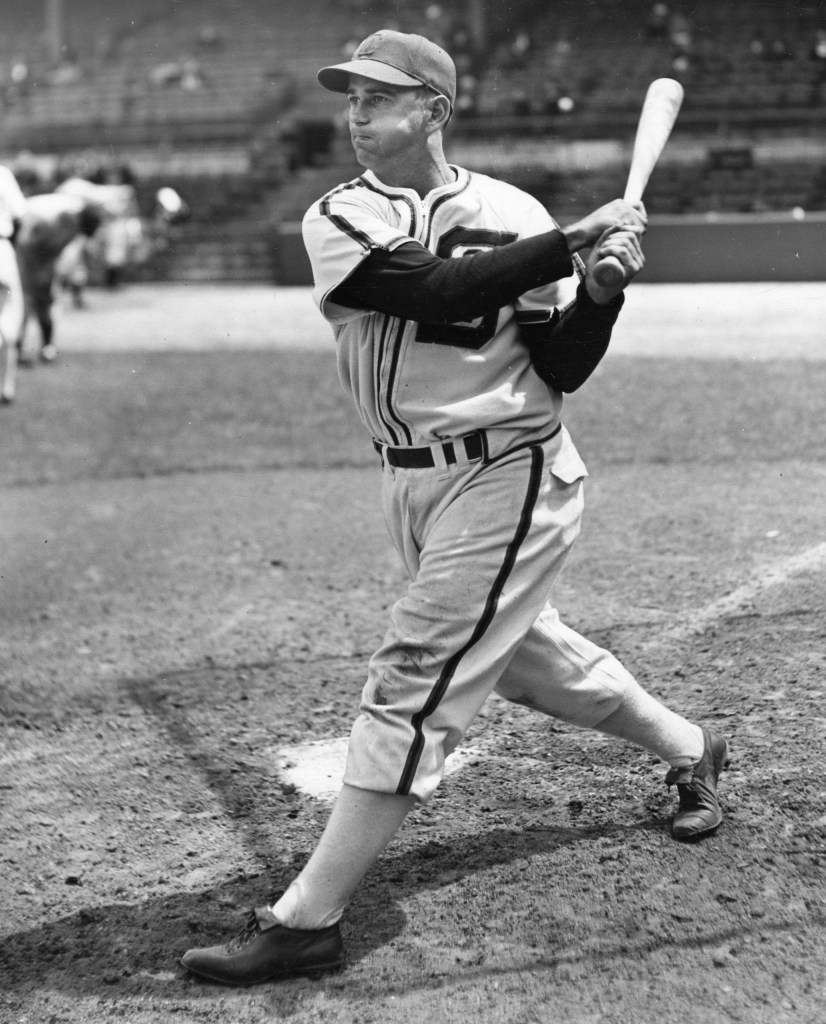

Another notable foul ball hitter was Luke Appling, the Hall of Fame shortstop with a career batting average of .310. As the story goes, Appling once asked White Sox management for a couple of dozen baseballs, so he could autograph them and donate them to charity. Management balked, citing a cost of several dollars per baseball. Appling bought the balls from his team, then went out that day and fouled off a couple dozen balls, after which he tipped his hat toward the owner’s box. He never had to pay for charity balls again, the legend goes.

Pepper Martin, Terry Moore & Ducky Medwick.

Another great foul ball story involves Pepper Martin and Joe Medwick of the St. Louis Cardinals famous Gas House Gang teams of the mid-1930s. With Martin at bat, Medwick took off from first base, intending to take third on the hit-and-run. Martin fouled the ball into the stands, and Reds catcher Gilly Campbell reflexively reached back to home plate umpire Ziggy Sears for a new ball. Then, just for fun, Campbell launched the ball down to third, where Sears, forgetting that a foul had just been hit and that he had given Campbell a new ball, called Medwick out. The Cardinals were furious, but not wanting to admit his error, Sears refused to reverse his call, and Medwick was thrown out-on a foul ball!

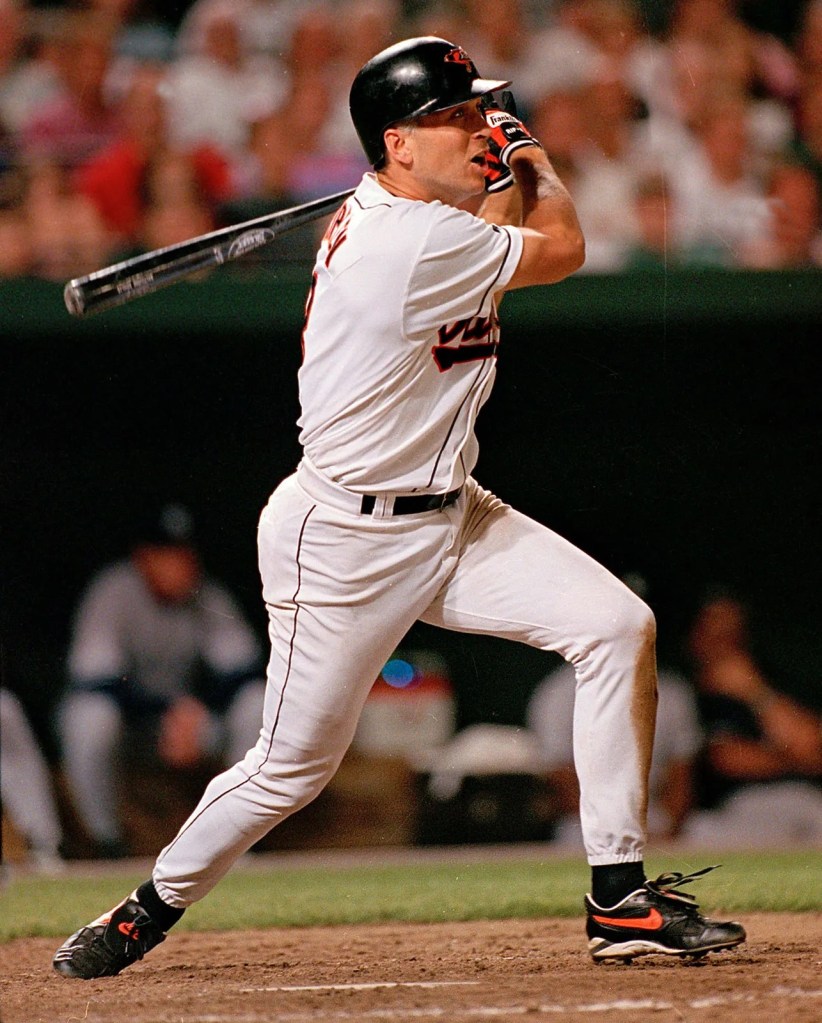

The great Cal Ripken Jr. made life imitate art with a foul ball in 1998. In the movie The Natural, Roy Hobbs lofts a foul ball at sportswriter Max Mercy, as Mercy sits in the stands drawing a critical cartoon of the slumping Hobbs. Baltimore Sun columnist Ken Rosenthal faced a similar wrath of the baseball gods after he wrote a column in 1998 suggesting that it might be time for Ripken to voluntarily end his streak, at that point several hundred games beyond Lou Gehrig’s old record, for the good of the team. Ripken responded by hitting a foul ball into the press box, which smashed Rosenthal’s laptop computer, ending its career. When told of his foul ball’s trajectory, Ripken responded with one word: “Sweet.”

Another sweet story involves a father and son combination. In 1999, Bill Donovan was watching his son Todd play center field for the Idaho Falls Braves of the Pioneer League. Todd made a nice diving catch and threw the ball back into the second baseman, who returned it to the pitcher. On the next pitch, a foul ball sailed into the outstretched hands of the elder Donovan. “I was like a kid when I caught it,” said the proud papa. “It made me wonder when was the last time that a father and son caught the same ball on consecutive pitches.”

One day in 1921, New York Giants fan Reuben Berman had the good fortune to catch a foul ball, or so he thought. When the ushers arrived moments later to retrieve the ball, Reuben refused to give it up, instead tossing it several rows back to another group of fans. The angered usher removed Berman from his seat, took him to the Giants’ offices, and verbally chastised him before depositing him in the street outside the Polo Grounds. An angry and humiliated Berman sued the Giants for mental and physical distress and won, leading the Giants, and eventually other teams, to change their policy of demanding foul balls be returned. The decision has come to be known as “Reuben’s Rule.”

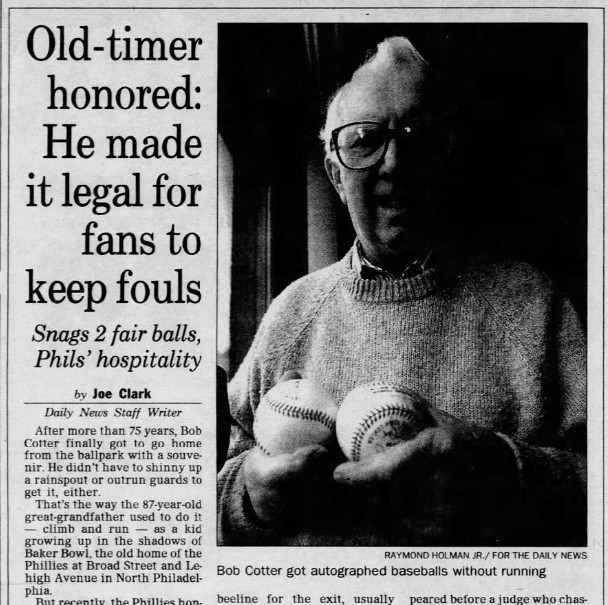

While Berman’s case was influential, the influence had not spread as far as Philadelphia by 1922, when 11-year-old fan Robert Cotter was nabbed by security guards after refusing to return a foul ball at a Phillies game. The guards turned him over to police, who put the little tyke in jail overnight. When he faced a judge the next day, young Cotter was granted his freedom, the judge ruling, “Such an act on the part of a boy is merely proof that he is following his most natural impulses. It is a thing I would do myself.” The tide eventually changed for good, and the practice of fans keeping foul balls became entrenched. World War II was another time when patriotic fans and owners worked together to funnel the fouls off to servicemen. A ball in the Hall of Fame’s collection is even stamped “From a Polo Grounds Baseball Fan,” one of the more than 80,000 pieces of baseball equipment donated to the war effort by baseball by June 1942.

One of those baseballs may well have been involved in one of the strangest of all foul ball stories. In a military communique datelined “somewhere in the South Pacific,” the story is told of a foul ball hit by Marine Private First Class George Benson Jr., which eventually traveled 15 miles. Benson’s batting practice foul looped up about 40 feet in the air, where it smashed through the windshield of a landing plane. The ball hit the pilot in the face, fracturing his jaw and knocking him unconscious. A passenger, Marine Corporal Robert J. Holm, muttering a prayer, pulled back on the throttle and prevented the plane from crashing, though he had never flown before. The pilot recovered momentarily and brought the plane to a landing at the next airstrip, 15 miles away.

In 1996, at the age of 71, former President Jimmy Carter made a barehanded catch of a foul ball hit by San Diego’s Ken Caminiti, while attending a Braves game. “He showed good hands,” said Braves catcher Javy Lopez.

With foul balls by this time an undeniable right for fans at the ballpark, what are your actual chances of catching a foul ball at a game? Well, to start with, the average baseball is in play for six pitches these days, which makes it sound as though there will be many chances to catch a foul ball in each game. While comprehensive statistics are not available, various newspapers have sponsored studies which, uncannily, seem quite often to come down to 22 or 23 fouls into the stands per game.

That seems like a healthy number until you look at average major league attendance at games. In the year 2000, the average game was attended by 29,938 fans. With 23 fouls per game, that works out to a 1 in 1,302 chance of catching a foul ball. With numbers like that, no wonder it feels so special to catch a foul ball. Nevertheless, those who yearn to catch a foul ball can improve their chances. I have listed some tips to help you bring home that elusive foul ball. Good luck!

The train was traveling on what would have been the 101st birthday of school founder and namesake John Purdue (born October 31, 1802). Purdue, a wealthy landowner, politician, educator and merchant, was the primary benefactor of the University. In 1903, if you wanted to get to Indianapolis from either school, you had three choices: ride a horse and buggy, walk or take the train. Since these were the days before automobile travel was popular, train travel was the most widely accepted form of transportation.

The train was traveling on what would have been the 101st birthday of school founder and namesake John Purdue (born October 31, 1802). Purdue, a wealthy landowner, politician, educator and merchant, was the primary benefactor of the University. In 1903, if you wanted to get to Indianapolis from either school, you had three choices: ride a horse and buggy, walk or take the train. Since these were the days before automobile travel was popular, train travel was the most widely accepted form of transportation.

Unlike the raucous fans traveling in the 13 plush, modern streamliner train coaches behind them, the Boilermakers team traveled in relative silence, focusing on the task at hand, mentally preparing for their upcoming rivalry game in the cozy confines of an older wooden train car. Unfortunately, the athletes had no idea that a minor mistake would lead to a major disaster. Railroad protocol specified that “Special” trains operate independent of the regular schedule. Timing was everything in the railroad game.

Unlike the raucous fans traveling in the 13 plush, modern streamliner train coaches behind them, the Boilermakers team traveled in relative silence, focusing on the task at hand, mentally preparing for their upcoming rivalry game in the cozy confines of an older wooden train car. Unfortunately, the athletes had no idea that a minor mistake would lead to a major disaster. Railroad protocol specified that “Special” trains operate independent of the regular schedule. Timing was everything in the railroad game.

The Boilermakers never knew what hit ’em. The engine slammed into the coal car, splintering apart the first few cars while folding like an accordion. When the two trains collided, the lead car hit the debris, causing it to shoot into the air. This gave the full impact to the second train car, causing all the deaths. The wooden train cars splintered like kindling and were destroyed, and the adjacent cars careened violently off the elevated tracks, tumbling to the ground below like jack straws.

The Boilermakers never knew what hit ’em. The engine slammed into the coal car, splintering apart the first few cars while folding like an accordion. When the two trains collided, the lead car hit the debris, causing it to shoot into the air. This gave the full impact to the second train car, causing all the deaths. The wooden train cars splintered like kindling and were destroyed, and the adjacent cars careened violently off the elevated tracks, tumbling to the ground below like jack straws. The Indianapolis star reported, “The trains came together with a great crash, which wrecked three of the passenger coaches, in addition to the engine and tender of the special train and two or three of the coal cars. The first coach on the special train was reduced to splinters. The second coach was thrown down a fifteen-foot embankment into the gravel pit and the third coach was thrown from the track to the west-side and badly wrecked. The coal cars plowed their way into the engine and demolished it completely. The coal tender was tossed to the side and turned over. A wild effort on the part of the imprisoned passengers to escape from the wrecked car followed the crash. Immediately following the wreck the students and the others turned their attention to the work of rescuing the injured, and by the time the first ambulances arrived many of the dead and suffering young men had been carried out and placed on the grass on both sides of the track.”

The Indianapolis star reported, “The trains came together with a great crash, which wrecked three of the passenger coaches, in addition to the engine and tender of the special train and two or three of the coal cars. The first coach on the special train was reduced to splinters. The second coach was thrown down a fifteen-foot embankment into the gravel pit and the third coach was thrown from the track to the west-side and badly wrecked. The coal cars plowed their way into the engine and demolished it completely. The coal tender was tossed to the side and turned over. A wild effort on the part of the imprisoned passengers to escape from the wrecked car followed the crash. Immediately following the wreck the students and the others turned their attention to the work of rescuing the injured, and by the time the first ambulances arrived many of the dead and suffering young men had been carried out and placed on the grass on both sides of the track.” The fans at the rear of the train were unaware of what happened and only felt a slight jolt as the train came to a sudden stop. These rearmost passengers wasted no time in coming to the assistance of the victims up ahead. The erstwhile revelers skidded to a stop at the scene of carnage and were horrified at the devastation before them. Acts of unselfish action made heroes out of athletes and ordinary people alike.

The fans at the rear of the train were unaware of what happened and only felt a slight jolt as the train came to a sudden stop. These rearmost passengers wasted no time in coming to the assistance of the victims up ahead. The erstwhile revelers skidded to a stop at the scene of carnage and were horrified at the devastation before them. Acts of unselfish action made heroes out of athletes and ordinary people alike. Seventeen passengers in the first coach were killed. Thirteen of the dead were members of the Purdue football team. Walter Bailey, a reserve player from New Richmond, although grievously injured, refused aid so that others could be helped. Team Captain Skeets Leslie was covered up for dead, his body transported to the morgue with the others. It was the first catastrophe to hit a major college sports team in the history of this country. The affects would be felt for decades to come and one of those players would rise from the dead, shake off accusations of association with Irvington KKK leader D.C. Stephenson, and lead his state and country through the Great Depression.

Seventeen passengers in the first coach were killed. Thirteen of the dead were members of the Purdue football team. Walter Bailey, a reserve player from New Richmond, although grievously injured, refused aid so that others could be helped. Team Captain Skeets Leslie was covered up for dead, his body transported to the morgue with the others. It was the first catastrophe to hit a major college sports team in the history of this country. The affects would be felt for decades to come and one of those players would rise from the dead, shake off accusations of association with Irvington KKK leader D.C. Stephenson, and lead his state and country through the Great Depression.