Original publish date: July 11, 2014

Original publish date: July 11, 2014

Although the anniversary date has recently passed, my mind wanders back to a sad incident from forty years ago. I was almost 12 years old and thunderstruck by the news, and even more stunned by the fact that no-one seemed to care about it as much as I did. I suppose age and experience have help me accept the fact that the incident that was so important to me four decades ago is even less remembered today.

On Sunday, June 30th, 1974, 23-year-old Ohio State University dropout Marcus Wayne Chenault, Jr. walked into Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta Georgia and shot dead the mother of Civil Rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Alberta Christine Williams King. Chenault also killed the church deacon, Edward Boykin, and injured another member of the congregation, Mrs. Jimmie Williams.

Alberta King was excited by the chance to play the church’s newly installed organ that morning during a reunion of past Ebenezer choir members. After all, Ebenezer Baptist was the church where her father, A.D. Williams, her husband, Martin Luther King Sr., and son, Martin Luther King Jr., all had served as pastors. As a pastor’s wife Alberta (called “Bunch” by her husband) followed in her mother’s footsteps as a powerful presence in Ebenezer’s affairs. She had grown up in Ebenezer and had played many significant roles at her beloved church; teacher, music director, official organizer, president of the Ebenezer Woman’s Council and church organist since 1932. As usual, Alberta was front and center that Sunday morning.

Conversely, nobody noticed as the short, chunky ex-MCL cafeteria busboy Chenault, wearing a tan suit and thick glasses, took a seat a few feet away from the organ. Later, co-workers would recall the otherwise nondescript young man they new as “Markie” telling anyone who would listen that “Someday, they would all be reading about me.” Mrs. King had just finished playing “The Lord’s Prayer” for the estimated 500 in attendance that day. Most of the congregation sat with their heads bowed and eyes closed in preparation for prayer when the shout: “I’m taking over here!” broke the silence. Chenault was standing on a pew at the front of the church with a deranged look in his eyes. He jumped down, bolted to the pulpit, faced the choir, and pulled out two guns. Chenault screamed “I’m tired of all this!” and then opened fire with both revolvers.

Chenault emptied both guns, killing Alberta King, church deacon Edward Boykin, and seriously wounding congregation member Mrs. Jimmie Mitchell. As the gunman sprinted out the side door leading to Jackson Street, the sanctuary was chaotic. Police apprehended Chenault quickly a short distance away.

After Chenault’s arrest, police found a hit list of names in his pocket that included 10 black clergymen and strangely, Aretha Franklin. Weeks before the incident, witnesses said that Markie went through numerous personality changes. One day he was an anti-communist; the next day a Black Panther militant. One day he was a Christian, the next, a Muslim or a Jew. One week he was chasing women, the next week he claimed to be homosexual.But mostly, Markie turned lonely and withdrawn. His motivation for the dastardly crime was a mystery.

After Chenault’s arrest, police found a hit list of names in his pocket that included 10 black clergymen and strangely, Aretha Franklin. Weeks before the incident, witnesses said that Markie went through numerous personality changes. One day he was an anti-communist; the next day a Black Panther militant. One day he was a Christian, the next, a Muslim or a Jew. One week he was chasing women, the next week he claimed to be homosexual.But mostly, Markie turned lonely and withdrawn. His motivation for the dastardly crime was a mystery.

Alberta King however, she was no mystery. Beloved by all, she was often referred to by her eldest son Martin as the moral foundation of his life. Mrs. King worked hard to instill self-respect into her three children. In an essay written at Crozer Seminary, Martin Luther King Jr. wrote that his mother “was behind the scenes setting forth those motherly cares, the lack of which leaves a missing link in life.” Martin Luther King Jr. was close to his mother throughout his life. Although her soft-spoken nature compelled her to avoid the publicity that accompanied her son’s international renown, she remained a constant source of strength to the King family, especially after King, Jr.’s assassination.

Chenault’s other murder victim Edward Boykin was also no mystery, having been a 39-year member of the church. At the time of his death, Boykin worked as a chauffeur for the widow of the late Clark Howell, Sr., former publisher of the Atlanta Constitution newspaper. He had served the Howell family for 32 years. He and his wife Lois had no children. Mrs Jimmie Wilson, the only surviving victim, was a 66-year-old retired teacher who considered herself lucky to be alive. She was quoted as saying, “He (the gunman) was standing right over me, and I was saying to myself, ‘this is it.'” before being struck in the lower neck by one of the bullets.

Details of the crime, the crime scene and the victim’s became well known, Chenault’s motive for such a dastardly crime was never discovered. The only thing for sure is that this was a seriously disturbed young man. Raised in the bluegrass country of Winchester, Ky., Chenault’s religious beliefs appeared to be a confused amalgam largely of his own devising. When he dropped out of Ohio State University, he was a junior majoring in education. The core of his personal religious philosophy was hatred of Christianity when, coupled with his sense of inadequacy and need for attention, became a lethal combination. Only two weeks before the killings he told a friend that he would soon “be all over the newspapers.”

According to the New York Times, Chenault “told the police that his mission was to kill the Rev. Martin Luther King Sr., but he shot Mrs. King instead because she was close to him”. During arraignment on murder charges, Chenault blamed his actions on a split personality, a “Hebrew” he called “Servant Jacob”. In court, Chenault was observed to be biting and licking his lips, and obsessively clasping his hands together while rocking back-and-forth. When asked about the shooting, he responded, “I’m a Hebrew and was sent here on a mission and it’s partially accomplished.” When Alberta’s widowed husband, Martin Luther King, Sr., asked Chenault why he did it, the youth replied: “Because she was a Christian and all Christians are my enemies.” He further claimed that he decided months earlier that “black ministers were a menace to black people and must be killed.”

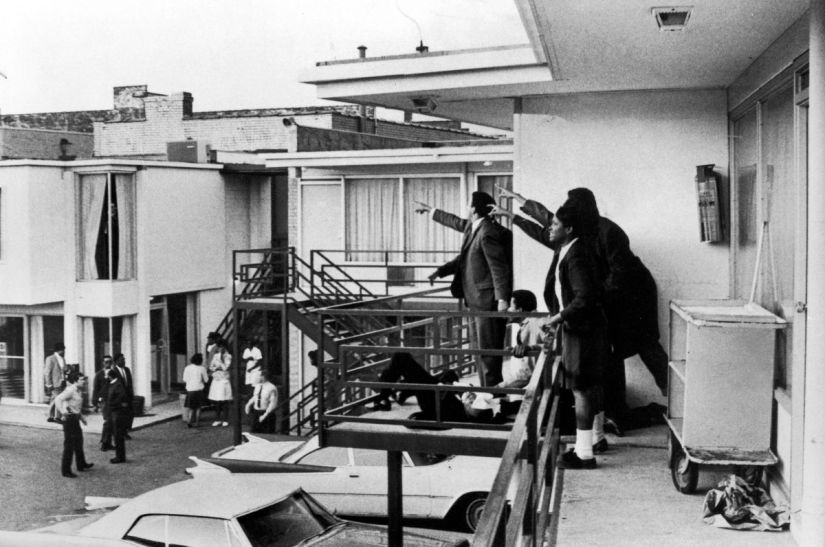

Alberta Williams King died at the age of 69 by the actions of little Markie Chenault. Her death was a shock to the congregation, the city, and the nation. In her honor, Atlanta mayor Maynard Jackson ordered the flags on all Atlanta city buildings to be flown at half-staff. Her body came back to Ebenezer Baptist Church to lie in state for public viewing, just a few feet from where she was shot. Alberta’s funeral was held at Ebenezer Baptist Church; U.S. representative from Georgia Andrew Young, who was on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel when her son was killed six years earlier, officiated at the service. Funeral attendees included members of the King family, second lady of the United States Betty Ford, and Georgia governor Jimmy Carter. She was buried in the same double mausoleum at Atlanta’s South-View cemetery that had previously held her son Martin Luther King, Jr.’s remains.

Alberta Williams King died at the age of 69 by the actions of little Markie Chenault. Her death was a shock to the congregation, the city, and the nation. In her honor, Atlanta mayor Maynard Jackson ordered the flags on all Atlanta city buildings to be flown at half-staff. Her body came back to Ebenezer Baptist Church to lie in state for public viewing, just a few feet from where she was shot. Alberta’s funeral was held at Ebenezer Baptist Church; U.S. representative from Georgia Andrew Young, who was on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel when her son was killed six years earlier, officiated at the service. Funeral attendees included members of the King family, second lady of the United States Betty Ford, and Georgia governor Jimmy Carter. She was buried in the same double mausoleum at Atlanta’s South-View cemetery that had previously held her son Martin Luther King, Jr.’s remains.

Bunch’s death was the crescendo of the often sad King family tenure at the church. Although Ebenezer remained a strong and vibrant congregation, it was never the same. Barely a year after her eldest son’s assassination in Memphis, Alberta King’s younger son, A.D., died in a mysterious accidental drowning.

A.D., like Martin Sr. & Jr., was a powerful, although much quieter, force in the Civil Rights Movement. In 1965, A.D. moved to Louisville, Kentucky, and became pastor at Zion Baptist Church. After his brother’s assassination in April 1968, there was speculation that A.D. might become the president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). A.D., however, made no effort to assume his deceased brother’s role, although he did continue to be active in the Poor People’s Campaign and in other work on behalf of SCLC.

After Martin’s death, A. D. King returned to Ebenezer Baptist Church, where in September 1968 he was installed as co-pastor. But by now, A.D. was struggling with alcohol and depression. On July 21, 1969, nine days before his 39th birthday, A. D. King was found dead in the swimming pool at his home. The cause of his death was listed as an accidental drowning.

His father said in his autobiography, “Alveda had been up the night before, she said, talking with her father and watching a television movie with him. He’d seemed unusually quiet…and not very interested in the film. But he had wanted to stay up and Alveda left him sitting in an easy chair, staring at the TV, when she went off to bed… I had questions about A.D.’s death and I still have them now. He was a good swimmer. Why did he drown? I don’t know — I don’t know that we will ever know what happened.” Naomi King, A.D.’s widow, said, “There is no doubt in my mind that the system killed my husband.”

His father said in his autobiography, “Alveda had been up the night before, she said, talking with her father and watching a television movie with him. He’d seemed unusually quiet…and not very interested in the film. But he had wanted to stay up and Alveda left him sitting in an easy chair, staring at the TV, when she went off to bed… I had questions about A.D.’s death and I still have them now. He was a good swimmer. Why did he drown? I don’t know — I don’t know that we will ever know what happened.” Naomi King, A.D.’s widow, said, “There is no doubt in my mind that the system killed my husband.”

Having lost both sons, Rev. King Sr. found the loss of his wife, especially in such a way, almost too much to bear and, not wanting “the church to decline under my leadership,” he tendered his resignation a short time after her death. By January 1975, the mighty King family was gone from Ebenezer Baptist Church. Years later Ebenezer dedicated it’s new pipe organ in their new sanctuary across the street in Alberta’s name to honor her “passion for beautiful worship music”.

Markie Chenault’s lawyers pleaded insanity stating that “the young man has repeatedly said he was on a mission to kill all Christians” but the defendant was given a death sentence for his crimes. During sentencing for the crime of capital murder, Chenault violently spat in the faces of his mother and father. The sentence was later reduced to life in prison, in part at the insistence of King family members who opposed the death penalty. His motivation remains unknown and Chenault took his secret to the grave. On August 22, 1995, he suffered a stroke in prison and died in hospital in the Atlanta suburb of Riverdale at the age of 44.

Again, through an act of violence, there ended a life that was totally nonviolent, a life that was thoroughly spiritual, a life that reflected love for all persons and unselfish service to humankind. Once more, the indomitable faith of the King family was tested, and again love prevailed amid sadness. The Rev. Martin Luther King, Sr., struck by the violent deaths of his two sons and by the tragic death of his wife Alberta, said at his beloved Bunch’s funeral service, “I cannot hate any man.” While her death is a tragic end to a life that sacrificed so much, I can’t help but feel that at least she died singing the Lord’s praises, surrounded by friends and family in the church she grew up in, was married in and where she raised a young man that would go on to change the world.

During this summer travel season, should you find yourself passing through the Sweet Auburn area of Atlanta, by all means stop in Ebenezer Baptist Church for awhile. There, you can sit in the same pews that witnessed the King’s in all their glory and all their sadness. The National Park Service maintains the historic church, there is no admission charged and you are invited to come in for a quiet respite while audio of Dr.Martin Luther King Jr.’s regular Sunday sermons are piped through the sanctuary. These are not the famous words we most associate with King, but rather his normal weekly lessons. And those sermons resonate to this day. But while there, take a moment to look up at that stage and remember Alberta Williams King. A quiet dignified servant of the Lord who cast a long shadow and left us too soon four decades ago.

Original publish date: January 24, 2014

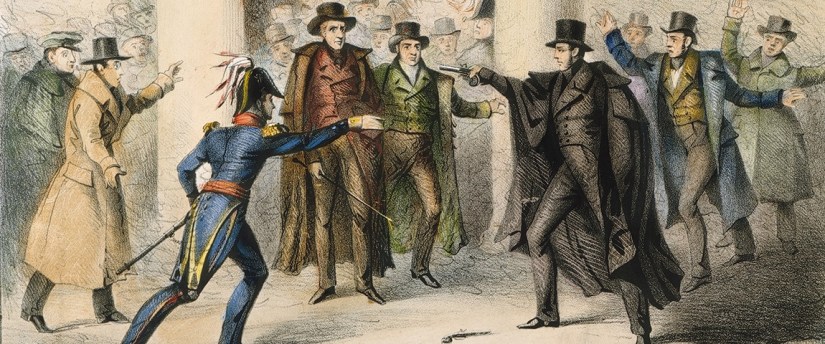

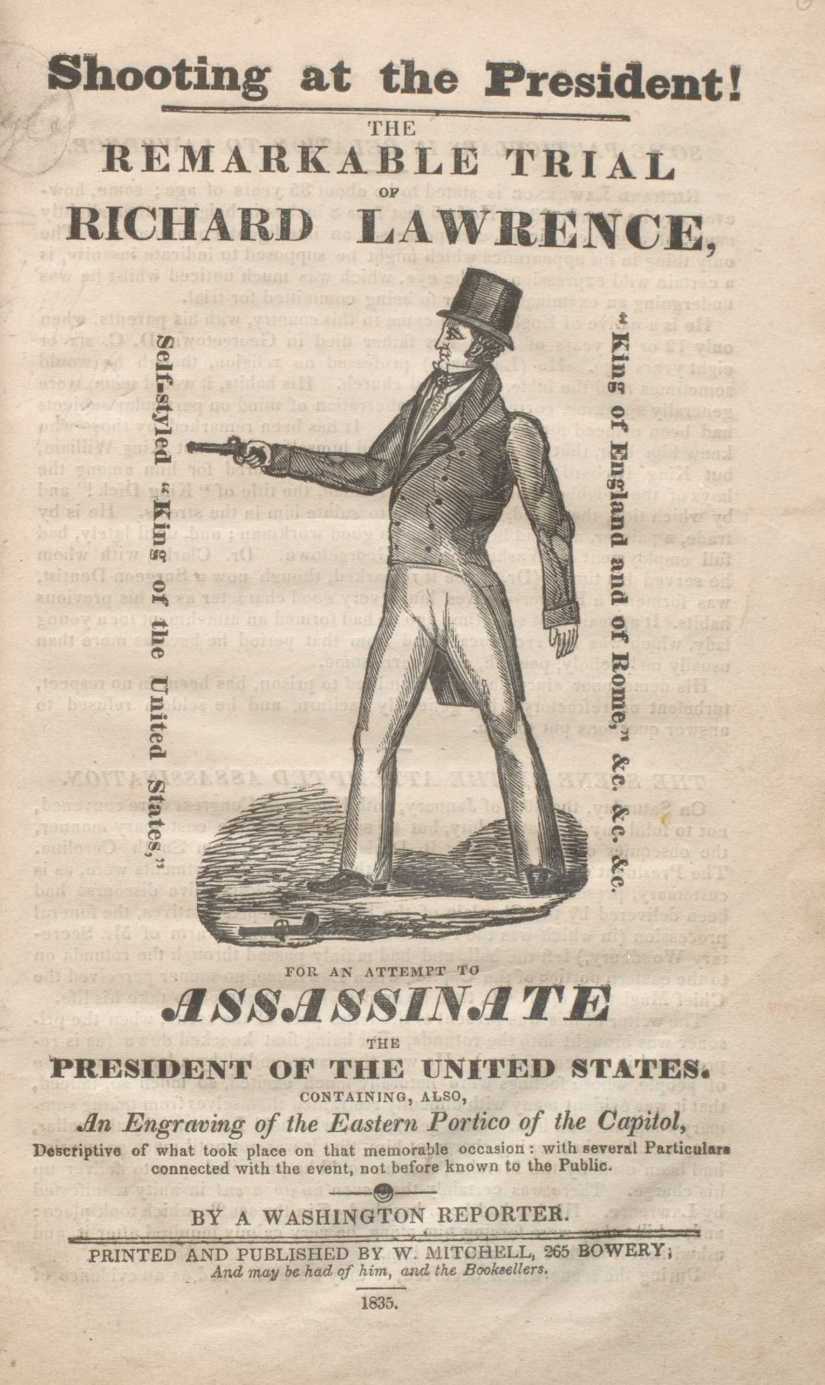

Original publish date: January 24, 2014 In November 1832, Lawrence announced to his family that he was returning to England. He left Washington, D.C. only to return a month later claiming that he decided not to go because it was too cold. Within weeks, he changed his mind and told friends & family that he was returning to England to study landscape painting. Lawrence left once again and got as far as Philadelphia before returning home. He told his family that the U.S. government had prevented him from traveling abroad and barred his planned return to England. He further claimed that while in Philadelphia, he read several newspaper stories about himself that were critical of his travel plans and his character. Lawrence told his family that he had no choice but to return to Washington, D.C. until such time as he could afford to hire his own ship and captain and sail away to England.

In November 1832, Lawrence announced to his family that he was returning to England. He left Washington, D.C. only to return a month later claiming that he decided not to go because it was too cold. Within weeks, he changed his mind and told friends & family that he was returning to England to study landscape painting. Lawrence left once again and got as far as Philadelphia before returning home. He told his family that the U.S. government had prevented him from traveling abroad and barred his planned return to England. He further claimed that while in Philadelphia, he read several newspaper stories about himself that were critical of his travel plans and his character. Lawrence told his family that he had no choice but to return to Washington, D.C. until such time as he could afford to hire his own ship and captain and sail away to England. Lawrence was brought to trial on April 11, 1835, at the District of Columbia City Hall. The prosecuting attorney was Francis Scott Key, author of the Star Spangled Banner. After only five minutes of deliberation, the jury found Lawrence “not guilty by reason of insanity.” In the years following his conviction, Lawrence was held by several institutions and hospitals. In 1855, he was committed to the newly opened Government Hospital for the Insane (later renamed St. Elizabeth’s Hospital) in Washington, D.C. There he remained until his death on June 13, 1861, almost 16 years to the day after his nemesis, Andrew Jackson, died on June 8, 1845.

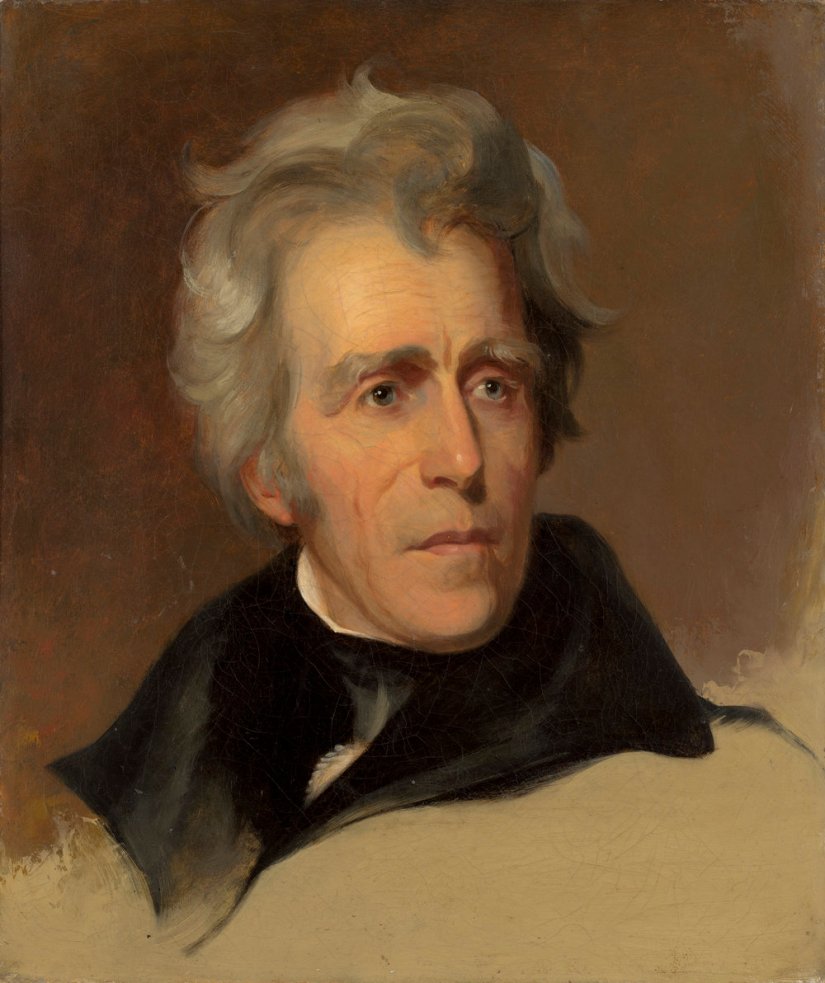

Lawrence was brought to trial on April 11, 1835, at the District of Columbia City Hall. The prosecuting attorney was Francis Scott Key, author of the Star Spangled Banner. After only five minutes of deliberation, the jury found Lawrence “not guilty by reason of insanity.” In the years following his conviction, Lawrence was held by several institutions and hospitals. In 1855, he was committed to the newly opened Government Hospital for the Insane (later renamed St. Elizabeth’s Hospital) in Washington, D.C. There he remained until his death on June 13, 1861, almost 16 years to the day after his nemesis, Andrew Jackson, died on June 8, 1845. Ironically, after the attack, Jackson returned by carriage to the White House and got back to business immediately. Several concerned citizens rushed to the President only to find him “calm, cool, and collected as if nothing had happened.” Another visitor arrived an hour later to find Jackson bouncing a child playfully on his knee while discussing the incident with General Winfield Scott. That evening, a thunderstorm swept the D.C. area blanketing the Capitol in thunder, lightning, and sheets of rain. Conversely, most Washingtonians never realized the storm they had just averted. Had those pistols met their mark, a literal firestorm would have swept our young nation. Eventually, the incident fed the legend that became Old Hickory. Love him or hate him, there are no gray areas with Andrew Jackson. He was a true American original.

Ironically, after the attack, Jackson returned by carriage to the White House and got back to business immediately. Several concerned citizens rushed to the President only to find him “calm, cool, and collected as if nothing had happened.” Another visitor arrived an hour later to find Jackson bouncing a child playfully on his knee while discussing the incident with General Winfield Scott. That evening, a thunderstorm swept the D.C. area blanketing the Capitol in thunder, lightning, and sheets of rain. Conversely, most Washingtonians never realized the storm they had just averted. Had those pistols met their mark, a literal firestorm would have swept our young nation. Eventually, the incident fed the legend that became Old Hickory. Love him or hate him, there are no gray areas with Andrew Jackson. He was a true American original. Original publish date: December 14, 2013

Original publish date: December 14, 2013

The mysterious stone was first noticed in 1998 and soon after word of the “Nick Beef” stone got out prompting would be grave hunters to ask the staff for directions to that stone, knowing that was the surest way to find Oswald’s. But nowadays, the staff is wise to that ploy and they won’t tell people where Nick Beef’s grave is either. But the question remains, who is / was Nick Beef?

The mysterious stone was first noticed in 1998 and soon after word of the “Nick Beef” stone got out prompting would be grave hunters to ask the staff for directions to that stone, knowing that was the surest way to find Oswald’s. But nowadays, the staff is wise to that ploy and they won’t tell people where Nick Beef’s grave is either. But the question remains, who is / was Nick Beef? Original publish date: December 7, 2013

Original publish date: December 7, 2013 Lee Harvey Oswald assassinated John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963 by firearm from the sixth floor of the Texas schoolbook depository in Dallas, Texas. Later that day, Oswald murdered Dallas police officer J. D. Tippit by shooting him four times on a Dallas street approximately 40 minutes after Kennedy. He was arrested while seated in the Texas Theatre a short time later and taken into police custody. On Sunday, November 24 Oswald was being led through the basement of Police Headquarters on his way to the county jail when, at 11:21 a.m., Dallas strip-club operator Jack Ruby stepped from the crowd and shot Oswald in the abdomen. Oswald died at 1:07 p.m. at Parkland Memorial Hospital-the same hospital where Kennedy had died two days earlier. A network television camera was broadcasting the transfer live and millions witnessed the shooting as it happened. After autopsy Oswald was buried in Fort Worth’s Rose Hill Memorial Burial Park.

Lee Harvey Oswald assassinated John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963 by firearm from the sixth floor of the Texas schoolbook depository in Dallas, Texas. Later that day, Oswald murdered Dallas police officer J. D. Tippit by shooting him four times on a Dallas street approximately 40 minutes after Kennedy. He was arrested while seated in the Texas Theatre a short time later and taken into police custody. On Sunday, November 24 Oswald was being led through the basement of Police Headquarters on his way to the county jail when, at 11:21 a.m., Dallas strip-club operator Jack Ruby stepped from the crowd and shot Oswald in the abdomen. Oswald died at 1:07 p.m. at Parkland Memorial Hospital-the same hospital where Kennedy had died two days earlier. A network television camera was broadcasting the transfer live and millions witnessed the shooting as it happened. After autopsy Oswald was buried in Fort Worth’s Rose Hill Memorial Burial Park. Original publish date: April 7, 2017

Original publish date: April 7, 2017

Jacqueline believed the Lorraine should be used for helping the poor and needy, rather than a celebration of Dr. King’s death. She told visitors that “Memphis has always been a city where the two biggest attractions are memorials to two dead men: Martin Luther King, Jr. and Elvis Presley.” Near Smith’s perch was a sign that read, “Stop worshiping the dead.” Smith argued that Dr. King’s legacy would have been better honored by converting the motel into low-income housing or a facility for the poor. “It’s a tourist trap, first and foremost… this sacred ground is being exploited.” Smith said of the museum that she never set foot in, despite invitations from the museum staff to do so. Smith’s call for a boycott has gone largely unheeded and she maintains her vigil outside the Loraine to this day.

Jacqueline believed the Lorraine should be used for helping the poor and needy, rather than a celebration of Dr. King’s death. She told visitors that “Memphis has always been a city where the two biggest attractions are memorials to two dead men: Martin Luther King, Jr. and Elvis Presley.” Near Smith’s perch was a sign that read, “Stop worshiping the dead.” Smith argued that Dr. King’s legacy would have been better honored by converting the motel into low-income housing or a facility for the poor. “It’s a tourist trap, first and foremost… this sacred ground is being exploited.” Smith said of the museum that she never set foot in, despite invitations from the museum staff to do so. Smith’s call for a boycott has gone largely unheeded and she maintains her vigil outside the Loraine to this day.