Original Publish date: March 19, 2018

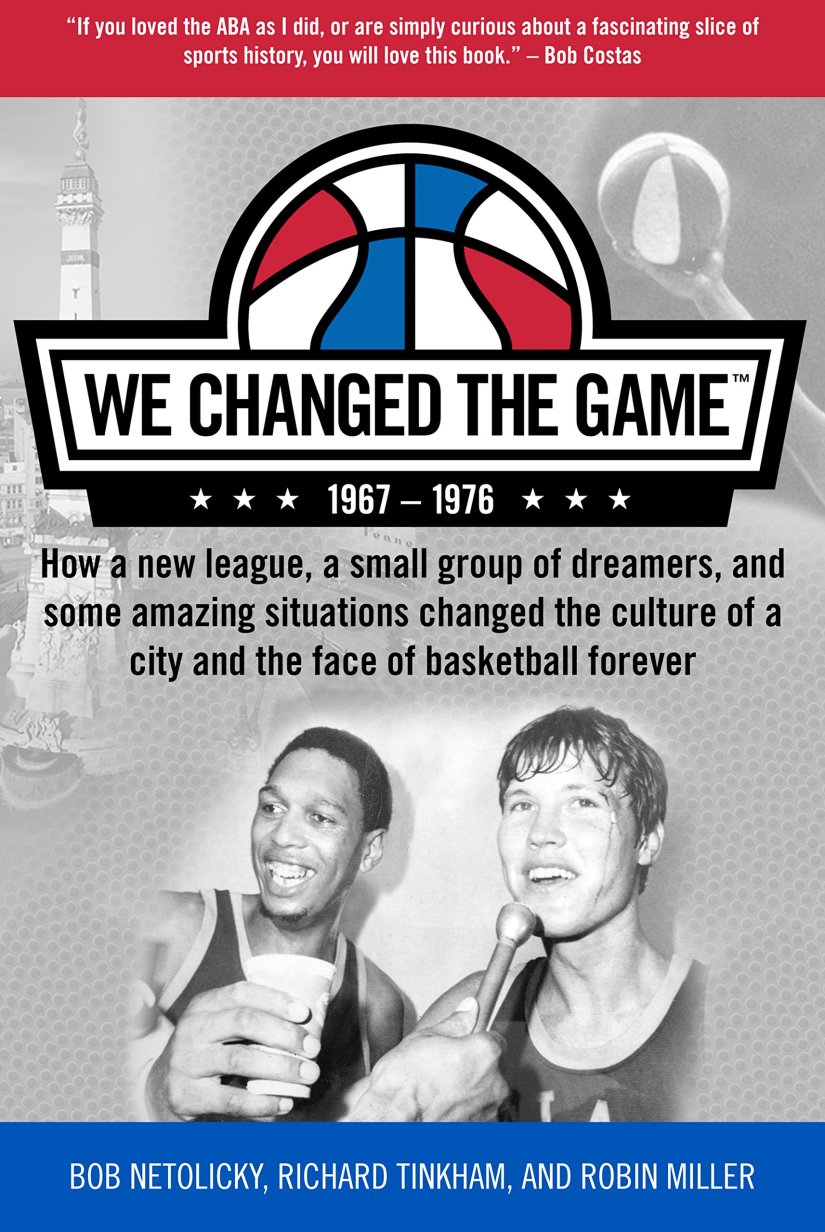

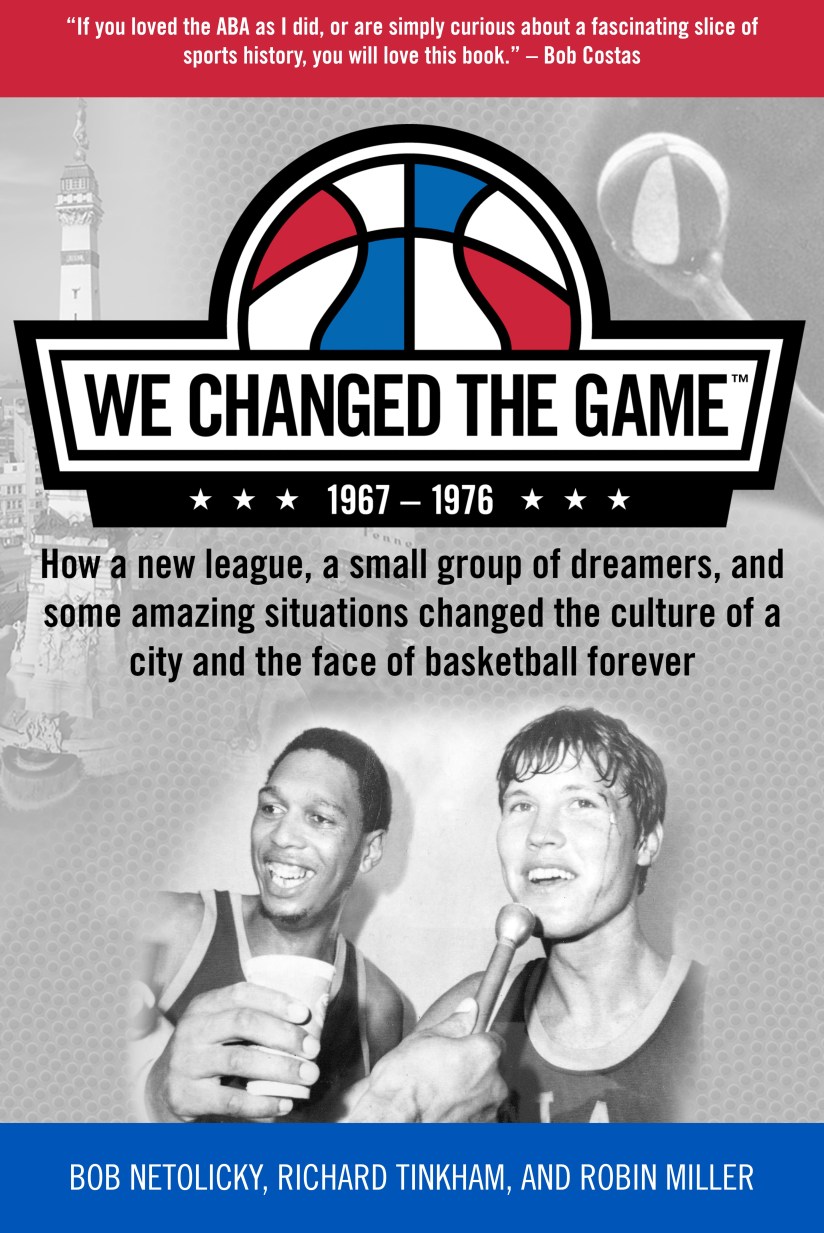

This past weekend the Irving Theatre played host to a book signing. Bob Netolicky, Robin Miller and Richard P. Tinkham visited the Irv for the official release party of their new book “We changed the game.” The book tells the story of the Indiana Pacers and the ABA from the very beginning by the men who lived it. Netolicky and Miller shared funny stories about the league that kept the crowd of 150 guests in stitches for the duration. However, even though he spoke in measured tones, sometimes barely above a whisper, it was Mr. Tinkham who kept the crowd on the edge of their seats.

Dick Tinkham is the Rosetta Stone of the American Basketball Association. He was there during the embryonic stages of the league forward. Dick explained how the ABA was originally designed to be a six-foot or under player league…gasp! He revealed how the Pacers team almost folded at the close of the 1968-69 season…gulp! And he continued with tales of crucial deals made in airports, hotel rooms, restaurants and bars…wheeze! Yes, Dick Tinkham knows where all the bodies are buried.

Dick Tinkham is the Rosetta Stone of the American Basketball Association. He was there during the embryonic stages of the league forward. Dick explained how the ABA was originally designed to be a six-foot or under player league…gasp! He revealed how the Pacers team almost folded at the close of the 1968-69 season…gulp! And he continued with tales of crucial deals made in airports, hotel rooms, restaurants and bars…wheeze! Yes, Dick Tinkham knows where all the bodies are buried.

Mr. Tinkham talked about early attempts by the ABA to lure Indianapolis native and hall of famer Oscar Robertson away from the NBA Cincinnati Royals. In 1967, Tinkham had hopes that Robertson might jump to the upstart Pacers. Robin Miller pointed out that Oscar had a $100,00 guaranteed contract and that “the Big O wasn’t going anywhere”. Mr. Tinkham then disclosed that it was Robertson who advocated that the Pacers travel to Dayton Ohio and check out a young man named Roger Brown. That signing changed the face of this city and arguably, saved the ABA. Ironically a few shot years later, Oscar Robertson would pop up again, this time as the foil for the ABA.

In June of 1971, only three years after the ABA began play, NBA owners voted 13–4 to work toward joining both leagues. A merger between the NBA and ABA appeared imminent and Dick Tinkham was right in the middle of it. After the 1970–71 season, Basketball Weekly reported: “The American basketball public is clamoring for a merger. So are the NBA and ABA owners, the two commissioners and every college coach. The war is over. The Armistice will be signed soon.” During this short-lived courtship, the two leagues agreed to play pre-season interleague exhibition games for the first time ever.

At last Saturday’s event in the Irving theatre, Dick Tinkham detailed how he met privately with Seattle SuperSonics owner Sam Schulman, a member of the ABA–NBA merger committee in 1971 to work out details for the merger. Schulman asked Tinkham how much it was going to take to get each ABA team (there were 11 at the time) to move into the NBA. Tinkham revealed to the gathered crowd that this was a question he had not anticipated and was totally unprepared to answer. Dick, thinking fast on his feet, replied that it would take $ 1 million for each team. Schulman agreed and phoned NBA Commissioner J. Walter Kennedy to announce that an agreement had been reached for a merger.

Schulman told the commissioner that he was so adamant about the merger that if the NBA did not accept the agreement, he would move the SuperSonics from the NBA to the ABA. Not only that, but Schulman threatened to move his soon-to-be ABA team to Los Angeles to compete directly with the Lakers. The owners of the Dallas Chaparrals (now the NBA’s San Antonio Spurs) were so confident of the impending merger that they suggested that the ABA hold off on scheduling and playing a regular season schedule for the 1971–72 season.

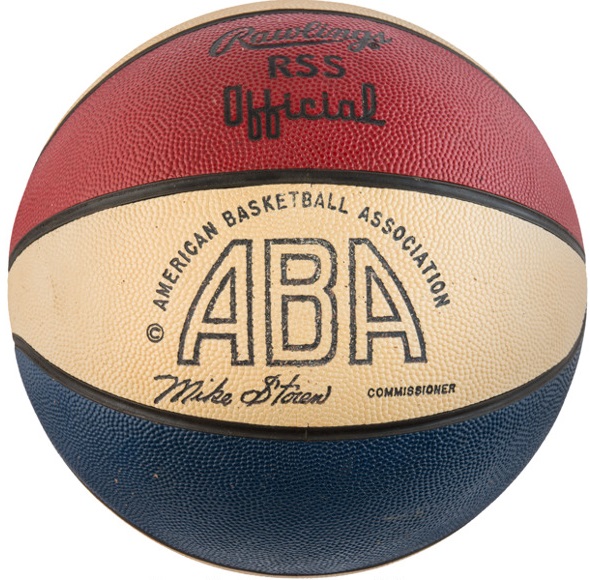

The first NBA vs. ABA exhibition game was played on September 21, 1971 at Moody Coliseum in Dallas, Texas. The first half was played by NBA rules and the second half by ABA rules, including the red, white and blue basketball and 3-point shot. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s NBA Milwaukee Bucks barely squeaked past John Beasley’s ABA Dallas Chaparrals, 106-103.

Down 12 points with 10 minutes to go, Chaps Gene Phillips hit six straight shots in fourth quarter to rally his team. The Chaps went ahead 103-102 with 24 seconds remaining on a pair of free throws from guard Donnie Freeman. With the Chap’s defense collapsing on Jabbar, McCoy McLemore hit a 15-foot jumper with 11 seconds left to give the Bucks a 104-103 lead. The Chaps’ Steve “Snapper” Jones missed a 10-foot baseline jumper with five seconds on the clock. Bucks Lucius Allen made two free throws for the final score. Bucks’ stars Oscar Robertson and Bob Dandridge missed the game. Dandridge was appearing in a Willamsburg Virginia court settling a traffic ticket and Oscar Robertson was in Washington D.C. fighting the merger.

Officially, the litigation was known as “Robertson v. National Basketball Association, 556 F.2d 682 (2d Cir. 1977)”, but it became forever known as the Oscar Robertson suit. Robertson, as president of the NBA Players Association, filed a lawsuit in April of 1970 to prevent the merger on antitrust grounds. Robertson, still smarting from his unexpected trade by his college hometown Cincinnati Royals to the Milwaukee Bucks, sought to block any merger of the NBA with the American Basketball Association, to end the option clause that bound a player to a single NBA team in perpetuity, to end the NBA’s college draft binding a player to one team, and to end restrictions on free agent signings. The suit also sought damages for NBA players for past harm caused by the option clause. The court issued an injunction against any merger thus delaying the ABA-NBA merger.

Robertson himself stated that his main gripe was that clubs basically owned their players: players were forbidden to talk to other clubs once their contract was up, because free agency did not exist back then. In 1972, the U.S. Congress came close to enacting legislation to enable a merger despite the Oscar Robertson suit. In September 1972, a merger bill was reported favorably out of a U.S. Senate committee, but the bill was put together to please the owners, and ended up not pleasing the Senators or the players. The bill subsequently died without coming to a floor vote. When Congress reconvened in 1973, another merger bill was presented to the Senate, but never advanced.

Meantime, the ABA-NBA exhibition games continued. In these ABA vs. NBA exhibition games, the ABA’s RWB ball was used for one half, and the NBA’s traditional brown ball was used in the other half, the ABA’s three-point shot (and 30 second shot clock) was used for one half only, in some games, the ABA’s no-foul out rule was in effect for the entire game and the league hosting the game provided its own referees. NBA refs wore the traditional B&W “zebra” shirts while ABA refs wore shorts matching the ball: red, white & blue. Most of the interleague games were played in ABA arenas because the NBA did not want to showcase (and legitimize) the ABA in front of NBA fans. On the flip side, ABA cities were eager to host NBA teams because they attracted extra fans, made more money, and proved both leagues could compete against each other. Results from those first few years were not highly publicized by either league.

Meantime, the ABA-NBA exhibition games continued. In these ABA vs. NBA exhibition games, the ABA’s RWB ball was used for one half, and the NBA’s traditional brown ball was used in the other half, the ABA’s three-point shot (and 30 second shot clock) was used for one half only, in some games, the ABA’s no-foul out rule was in effect for the entire game and the league hosting the game provided its own referees. NBA refs wore the traditional B&W “zebra” shirts while ABA refs wore shorts matching the ball: red, white & blue. Most of the interleague games were played in ABA arenas because the NBA did not want to showcase (and legitimize) the ABA in front of NBA fans. On the flip side, ABA cities were eager to host NBA teams because they attracted extra fans, made more money, and proved both leagues could compete against each other. Results from those first few years were not highly publicized by either league.

Although they didn’t count for anything except pride, ABA / NBA exhibition games were always intense due to the bad blood between the leagues. During these ultra-competitive games players (including future Hall of Famers Rick Barry and Charlie Scott who played for teams in both leagues) were thrown out with multiple technical fouls. Likewise, Hall of Fame coaches like Larry Brown and Slick Leonard (who coached in both leagues) often ended up listening to interleague games in the locker room after being ejected.

After the 1974-75 regular season, the ABA Champion Kentucky Colonels formally challenged the NBA Champion Golden State Warriors to a “World Series of Basketball,” with a winner-take-all $1 Million purse (collected from anticipated TV revenues). The NBA and the Warriors refused the challenge. Again, after the 1975-76 season, the ABA Champion New York Nets offered to play the NBA Champion Boston Celtics in the same fashion, with the proceeds going to benefit the 1976 United States Olympic team. Predictably, the Celtics declined to participate.

In the later years of the rivalry, buoyed by younger players, better talent and the home court advantage, ABA teams began winning most of the games. Over the last three seasons of the rivalry, the ABA steadily pulled ahead: 15-10 (in 1973), 16-7 (in 1974), and 31-17 (in 1975). The ABA won the overall interleague rivalry, 79 games to 76 and in every matchup of reigning champions from the two leagues, the ABA champion won, including in the final pre-merger season when the Kentucky Colonels defeated the Golden State Warriors, sans $ 1 million dollar purse.

The Oscar Robertson suit would eventually seal the fate of the ABA and for the entirety of its pendency it presented an insurmountable obstacle to the desired merger of the two leagues. The worm was beginning to turn.

Next Week- Part II including details of the April 7, 2018 American Basketball Association Reunion in Indianapolis.

Original publish date: November 1, 2013

Original publish date: November 1, 2013 Original publish date: March 11, 2018

Original publish date: March 11, 2018 The nicest thing about this book is that, in many instances, it defines the folklore of the league by telling the real story from the men who actually lived it. For me, the book’s bombshell revelation is the story of just how close the Pacers came to folding at the close of the 1968-69 season. Before that second season, the Pacers made the greatest trade in team history, sending Jimmy Dawson, Ron Kozlicki and cash to the Minnesota / Miami franchise for ABA Rookie of the Year Mel Daniels. That trade, along with the hing of Leonard as the new head coach, legitimized the team. After starting the season 2-7, the team went 42-27 the rest of the way, winning the Eastern Division by 1 game over Miami. However, the Pacers found themselves down 3 games to 1 against the rival Kentucky Colonels in the first round of the league playoffs.

The nicest thing about this book is that, in many instances, it defines the folklore of the league by telling the real story from the men who actually lived it. For me, the book’s bombshell revelation is the story of just how close the Pacers came to folding at the close of the 1968-69 season. Before that second season, the Pacers made the greatest trade in team history, sending Jimmy Dawson, Ron Kozlicki and cash to the Minnesota / Miami franchise for ABA Rookie of the Year Mel Daniels. That trade, along with the hing of Leonard as the new head coach, legitimized the team. After starting the season 2-7, the team went 42-27 the rest of the way, winning the Eastern Division by 1 game over Miami. However, the Pacers found themselves down 3 games to 1 against the rival Kentucky Colonels in the first round of the league playoffs. For sure, there will be other book signings for “We Changed the Game”. Thus far Neto has scheduled a signing at the J & J all-star sportscard show on Saturday March 24th from 10:00 to 12:00. The card show is held at the American Legion Post # 470 at 9091 E. 126th St. in Fishers and then again at Saturday March 31st from Noon to 2:00 at Bruno’s Shoebox 50 North 9th St. in Noblesville. Bruno’s shoebox is owned and operated by former longtime Indianapolis Star / News reporter and Indiana Pacers webmaster Conrad “Bruno” Brunner.

For sure, there will be other book signings for “We Changed the Game”. Thus far Neto has scheduled a signing at the J & J all-star sportscard show on Saturday March 24th from 10:00 to 12:00. The card show is held at the American Legion Post # 470 at 9091 E. 126th St. in Fishers and then again at Saturday March 31st from Noon to 2:00 at Bruno’s Shoebox 50 North 9th St. in Noblesville. Bruno’s shoebox is owned and operated by former longtime Indianapolis Star / News reporter and Indiana Pacers webmaster Conrad “Bruno” Brunner. Original publish date: May 2, 2017

Original publish date: May 2, 2017 The ABA Indiana Pacers were the powerhouse of the old American Basketball Association, appearing in the league finals five times and winning three Championships in nine-years. By the time of the NBA-ABA merger in 1976, the Pacers had established themselves as the league’s elite. The players were household names and their reputation was now legend. The crowds at the State Fair Coliseum, and later Market Square Arena, where the Pacers held court were always dotted with celebrities from all walks of life. In the Circle City of the seventies, everyone wanted an association with the Pacers. In short, they were rock stars.

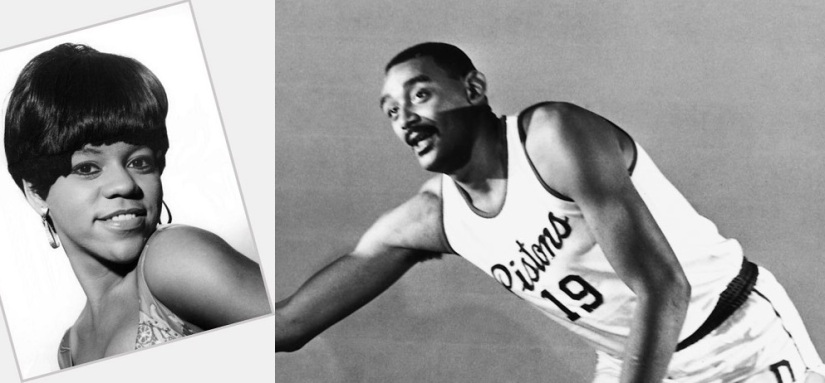

The ABA Indiana Pacers were the powerhouse of the old American Basketball Association, appearing in the league finals five times and winning three Championships in nine-years. By the time of the NBA-ABA merger in 1976, the Pacers had established themselves as the league’s elite. The players were household names and their reputation was now legend. The crowds at the State Fair Coliseum, and later Market Square Arena, where the Pacers held court were always dotted with celebrities from all walks of life. In the Circle City of the seventies, everyone wanted an association with the Pacers. In short, they were rock stars. Young Marvin, who would grow to be over 6 feet tall, became a fixture on the tough D.C. basketball courts. One of his neighbors was future Detroit Mayor and Pistons All-star Dave Bing. Although smaller and four years younger, Bing played alongside Gaye on those DC project courts. The two men forged a friendship that lasted the rest of their lives. Bing continued to excel on the court as Marvin’s skills faded. Ironically, both men landed in Detroit. Gaye turned to song, which led him to Motown immortality; Bing landed in the Basketball Hall of Fame.

Young Marvin, who would grow to be over 6 feet tall, became a fixture on the tough D.C. basketball courts. One of his neighbors was future Detroit Mayor and Pistons All-star Dave Bing. Although smaller and four years younger, Bing played alongside Gaye on those DC project courts. The two men forged a friendship that lasted the rest of their lives. Bing continued to excel on the court as Marvin’s skills faded. Ironically, both men landed in Detroit. Gaye turned to song, which led him to Motown immortality; Bing landed in the Basketball Hall of Fame. While Marvin was busy helping Berry Gordy shape the sound of Motown in the 1960s, he never lost his love of sports. The “Prince of Soul” recorded iconic concept albums including What’s Going On and Let’s Get It On while keeping active on the courts, courses and fields around the Motor City. In the book “Divided Soul; The Life of Marvin Gaye”, author David Ritz says, “Gaye was a good athlete, but not of professional quality. His football playing, just like his basketball playing (where he loved to hog the ball and shoot) were further examples of his delusions of grandeur.” Gaye was a regular at celebrity golf tournaments and loved rubbing elbows with pro athletes like Bob Lanier, Gordie Howe and Willie Horton.

While Marvin was busy helping Berry Gordy shape the sound of Motown in the 1960s, he never lost his love of sports. The “Prince of Soul” recorded iconic concept albums including What’s Going On and Let’s Get It On while keeping active on the courts, courses and fields around the Motor City. In the book “Divided Soul; The Life of Marvin Gaye”, author David Ritz says, “Gaye was a good athlete, but not of professional quality. His football playing, just like his basketball playing (where he loved to hog the ball and shoot) were further examples of his delusions of grandeur.” Gaye was a regular at celebrity golf tournaments and loved rubbing elbows with pro athletes like Bob Lanier, Gordie Howe and Willie Horton. Original publish date: March 19 2017

Original publish date: March 19 2017