Original publish date: July 27, 2017

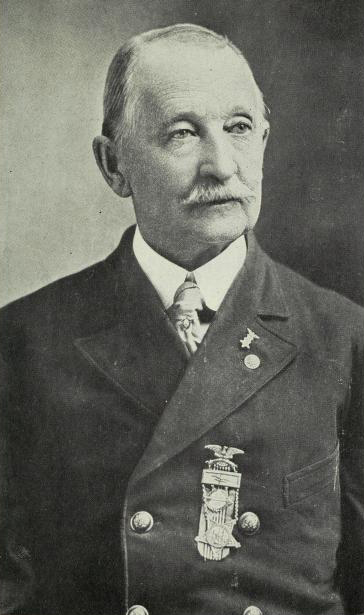

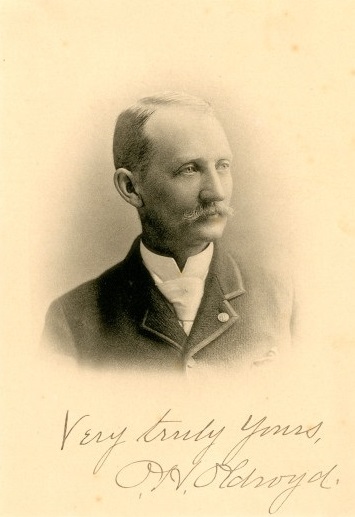

I have spent the last 3 weeks retracing the steps I have taken chasing one of my heroes, Osborn Oldroyd. In early June of this year, I was contacted by a Marshalltown, Iowa auction house that informed me of a small group of items they were auctioning off that came from the Oldroyd Museum in Springfield. There were 10 items in the sale that could be directly traced to Osborn Oldroyd’s museum, and all 10 were marked “Property of O.H. Oldroyd” in one form or another.

On June 16th I found myself in Marshalltown examining the items. I obtained my bidder number, which happened to be bidder # 1, and retreated to my hotel room to await the next day’s auction. There’s not much to do in Marshalltown, Iowa so I decided to drive to the nearby community of LeClaire, Iowa to mark time.

On June 16th I found myself in Marshalltown examining the items. I obtained my bidder number, which happened to be bidder # 1, and retreated to my hotel room to await the next day’s auction. There’s not much to do in Marshalltown, Iowa so I decided to drive to the nearby community of LeClaire, Iowa to mark time.

LeClaire rests a stone’s throw from the Mississippi River. The town is best known as the home of TV’s American Pickers. The duo’s Antique Archaeology headquarters is a converted gas station and car wash atop a small rise on the west side of the river. I pulled in about 9:30 in the morning, a half hour before they opened, and drove slowly through a crowd of some thirty people who all stopped and stared at me uncomfortably as I cruised past. I soon realized that these people were checking me out carefully to make sure I wasn’t one of “them”. The disappointment was palpable as they realized I wasn’t Frank Fritz or Mike Wolfe. I walked around the buildings, looked through the windows, and since I wasn’t in the market for a 10-foot gas station or junk car and didn’t need any American Pickers t-shirts, coffee mugs, hats, or water bottles, I headed back to Marshalltown.

The Oldroyd lots were in the middle of a 600-lot sale billed as a “Gentlemen’s Items and Silver Collector’s Auction” by the Tom Harris auction house. So I sat patiently and watched nearly 200 items (mostly an assortment of old-fashioned silver match safes) get gaveled down before my first item came up on the auction block. I won’t bore you any further with a blow-by-blow account of each item’s bidding and disposition, however, when the dust cleared, I had won 8 out of 10 Oldroyd items sold that day. Why not 10 out of 10, you ask? Well, as I am not independently wealthy, I decided it best to let 2 lots (a pair of eyeglasses with a dubious claim to fame and a cabinet photo made after Lincoln’s death) be sacrificed for the acquisition of the other 8.

Among the items I brought home were a pair of contemporaneous framed leaflets. Both are displayed starkly in black wood and glass frames, one is a copy of Lincoln’s farewell address to the citizens of Springfield, and the other is a copy of Lincoln’s favorite poem. The farewell address is important to me because Lincoln’s first stop after the delivery of this poignant edict was Indianapolis. The next item was a classic-looking photo of Lincoln ascending to heaven wrapped in the open arms of George Washington. The careworn oval metal frame fits snugly in the palm and bears the wear and patina of an item held repeatedly in the loving hands of a legion of Lincoln admirers.

Among the items I brought home were a pair of contemporaneous framed leaflets. Both are displayed starkly in black wood and glass frames, one is a copy of Lincoln’s farewell address to the citizens of Springfield, and the other is a copy of Lincoln’s favorite poem. The farewell address is important to me because Lincoln’s first stop after the delivery of this poignant edict was Indianapolis. The next item was a classic-looking photo of Lincoln ascending to heaven wrapped in the open arms of George Washington. The careworn oval metal frame fits snugly in the palm and bears the wear and patina of an item held repeatedly in the loving hands of a legion of Lincoln admirers.

The next item is the haunting life mask of Abraham Lincoln that once hung on the wall of Oldroyd’s museum. The lifesized mask is attached to a larger handcrafted oval wooden plaque with a smaller brass nameplate attached to the front. The lifemask, made by artist Leonard Volk in 1860 before Lincoln grew his signature beard, is an accurate representation of what it would have been like to look at the face of a young and vibrant Lincoln. This item was surely a highlight of the museum and, judging by the loss of paint and subsequent repair of the nose, was a good luck talisman for all visitors. Rubbing Lincoln’s nose is still a popular tradition at the Lincoln tomb in Springfield.

The next item is the haunting life mask of Abraham Lincoln that once hung on the wall of Oldroyd’s museum. The lifesized mask is attached to a larger handcrafted oval wooden plaque with a smaller brass nameplate attached to the front. The lifemask, made by artist Leonard Volk in 1860 before Lincoln grew his signature beard, is an accurate representation of what it would have been like to look at the face of a young and vibrant Lincoln. This item was surely a highlight of the museum and, judging by the loss of paint and subsequent repair of the nose, was a good luck talisman for all visitors. Rubbing Lincoln’s nose is still a popular tradition at the Lincoln tomb in Springfield.

The next item was, according to Oldroyd, the last Bible that the Lincoln family ever  owned. The Bible was obtained by Oldroyd after Mr. Lincoln was killed and presumably following the death of Mary and Tad Lincoln. The phone book-sized Bible shows signs of heavy wear and transport in compliance with the somewhat vagabond lifestyle led by Mary and Tad after vacating the White House in 1865. Mary died in 1882. Tad preceded her in 1871. The Bible includes a couple pages of contemporary Carte de Visite photographs of the Lincoln family along with a few other disparate images from the Civil War and immediate post-period. The inclusion of CDVs depicting Union Civil War Generals Grant, Sheridan, Burnside, and Sherman alongside images of the US Capitol Dome under construction and George and Martha Washington could easily be construed as Tad’s version of collecting baseball cards.

owned. The Bible was obtained by Oldroyd after Mr. Lincoln was killed and presumably following the death of Mary and Tad Lincoln. The phone book-sized Bible shows signs of heavy wear and transport in compliance with the somewhat vagabond lifestyle led by Mary and Tad after vacating the White House in 1865. Mary died in 1882. Tad preceded her in 1871. The Bible includes a couple pages of contemporary Carte de Visite photographs of the Lincoln family along with a few other disparate images from the Civil War and immediate post-period. The inclusion of CDVs depicting Union Civil War Generals Grant, Sheridan, Burnside, and Sherman alongside images of the US Capitol Dome under construction and George and Martha Washington could easily be construed as Tad’s version of collecting baseball cards.

The last three items of acquisition were perhaps the most important to me. I am a native Hoosier. I cherish the idea that Abraham Lincoln grew to manhood in the southern region of my home state. These three items offered a direct connection to Lincoln and Indiana. The first two items are innocuous in their relevance to Lincoln the Hoosier; the Lincoln family coffee grinder and Abraham Lincoln’s ice skate.

The last three items of acquisition were perhaps the most important to me. I am a native Hoosier. I cherish the idea that Abraham Lincoln grew to manhood in the southern region of my home state. These three items offered a direct connection to Lincoln and Indiana. The first two items are innocuous in their relevance to Lincoln the Hoosier; the Lincoln family coffee grinder and Abraham Lincoln’s ice skate.

The ancient-looking coffee grinder consists of a sturdy metal handle crank sprouting from the top of a wooden cabinet tower. The coffee maker’s tower was likely constructed by Abraham Lincoln’s father Thomas, a carpenter by trade. Hidden at the foot of the cabinet is a small drawer designed to catch the ground-up remains of coffee beans. The Lincoln homestead in Spencer County was part of the western frontier when the family arrived in 1816. Many diaries and letters confirm the importance of coffee to Western pioneers. In his diary, Josiah Gregg, a frontier trapper, wrote about the pioneers’ love of coffee. “The insatiable appetite acquired by travelers upon the Prairies is almost incredible, and the quantity of coffee drank is still more so,” he wrote. “It is an unfailing and apparently indispensable beverage, served at every meal.” This innocent-looking household appliance would have been one of the most cherished articles owned by the Lincoln family as young Abe grew up.

The next Indiana Lincoln item is an ice skate. The thick wooden shoe stand is shaped like an hourglass and the heavy iron blade is curled at each end like an ancient Crakow shoe. While no official reference exists of Lincoln the ice skater, the skate presents a romantic image of boyhood Lincoln at play on a frozen southern Indiana pond. Simply holding it in your hands brings a smile to your face.

The next Indiana Lincoln item is an ice skate. The thick wooden shoe stand is shaped like an hourglass and the heavy iron blade is curled at each end like an ancient Crakow shoe. While no official reference exists of Lincoln the ice skater, the skate presents a romantic image of boyhood Lincoln at play on a frozen southern Indiana pond. Simply holding it in your hands brings a smile to your face.

The last item I purchased was the one I had resolved was heading back home to Indiana  with me, at all costs. It is an ancient-looking Colonial Era metal candle maker. During colonial times up to the Antebellum Era, candles were the main source of light during the long, dark, nighttime hours. Candles on the western frontier were made from beeswax and tallow (animal fat). The wicks were lain loosely inside the tube as the wax was poured in around them to harden.

with me, at all costs. It is an ancient-looking Colonial Era metal candle maker. During colonial times up to the Antebellum Era, candles were the main source of light during the long, dark, nighttime hours. Candles on the western frontier were made from beeswax and tallow (animal fat). The wicks were lain loosely inside the tube as the wax was poured in around them to harden.

Included with the candle maker is a framed certificate written and signed by Osborn Oldroyd reading: “This candle maker is from the Lincoln and Sparrow Cabin on Pigeon Creek Indiana (1818-1835) O.H. Oldroyd Washington April 9, 1901”. The certificate has a small brass diecut tab attached with the seal of the state of Indiana inset. It would be hard to find a more romantic artifact to illustrate Lincoln’s time spent in the Hoosier state. Young Abraham may well have learned to read by the light of a candle made in this, the Lincoln family candle mold. Stories abound of Young Abe the railsplitter reading by candle and firelight into the wee hours of the morning after a long day’s work in the fields.

Included with the candle maker is a framed certificate written and signed by Osborn Oldroyd reading: “This candle maker is from the Lincoln and Sparrow Cabin on Pigeon Creek Indiana (1818-1835) O.H. Oldroyd Washington April 9, 1901”. The certificate has a small brass diecut tab attached with the seal of the state of Indiana inset. It would be hard to find a more romantic artifact to illustrate Lincoln’s time spent in the Hoosier state. Young Abraham may well have learned to read by the light of a candle made in this, the Lincoln family candle mold. Stories abound of Young Abe the railsplitter reading by candle and firelight into the wee hours of the morning after a long day’s work in the fields.

The reference by Oldroyd to the “Lincoln-Sparrow” cabin is an obscure one, recognized by only the most astute Lincoln scholar. Elizabeth and Thomas Sparrow (Nancy’s maternal aunt and uncle), moved in with the Lincoln family at Pigeon (or Pidgin) Creek in 1817 a year before Captain Oldroyd’s certificate denotes. The Lincolns had just finished their cabin and moved out of their 3-sided lean-to, later known as the “half-faced camp”. The Sparrows were given the lean-to to live in while they built their cabin. Shortly after the Sparrows arrived, Nancy bought six milk cows to provide milk for the two families. In the fall of 1818, an illness known as “the milk-sick” swept the area. People at Pigeon Creek were dying from drinking milk. To be safe the Lincolns and Sparrows kept the children from drinking milk. However, the adults of both families drank it for almost two years before becoming sick. Lincoln’s “Angel Mother” and the Sparrows all died of the milk sickness. 9-year-old Abraham Lincoln never really got over the childhood loss.

So now you can see why these items were so important for me to bring back to Indiana. They belong here. Ironically, two days after I returned from my Iowa Oldroyd journey, I was visited in my home by WISH-TV 8 reporter Dick Wolfsie. Dick was on a visit to film a segment (which as of this writing has not aired) for a Saturday morning broadcast about collectors and their collections. The items were so new to me that they remained spread out on the kitchen counter with the original auction lot number tags attached.

Like me, Mr. Wolfsie was excited to handle the items. He was drawn in particular to the Lincoln Family Bible which was featured prominently in the segments. He was also drawn to the Lincoln ice skate. How could anyone not be drawn to Abe Lincoln’s ice skate? Dick’s only question was “Where is the other one?” The segments will air soon and can be viewed by going to Dick Wolfsie’s Channel 8 webpage and clicking on his profile and segment list.

A few days later, I received a phone call from representatives of the American Pickers crew. Seems that Frank and Mike were on their way to Indiana in search of stories and things to buy. I informed them that while I certainly had stories to share, I had nothing to sell. We took a mutual pass.

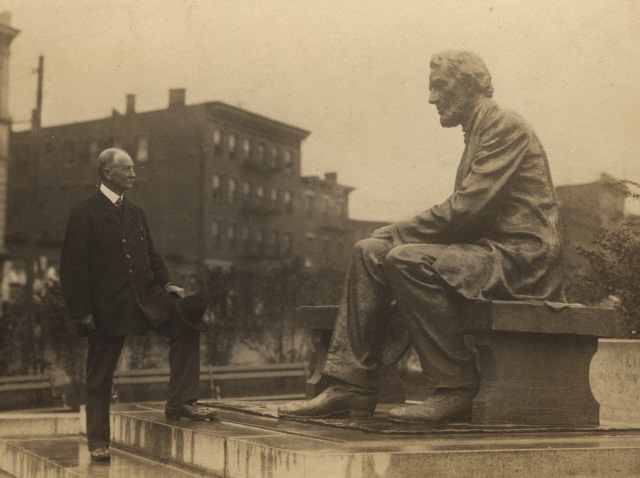

Lastly, my wife treated me to a birthday trip to Springfield, Illinois in July. I traveled to the Lincoln home on an early Saturday morning to reflect while seated in front of the Lincoln home. Based on trips past, I’ve learned that the early morning hours are best. No school buses, tourists or fitness walkers/bikers to mar the scene. I have been coming to Springfield for many years. Of course, Abraham Lincoln is the reason for my visit. However, I never forget that Osborn Oldroyd lived in the house and operated his museum here for nearly a decade (1884-93). I’d asked several people, ranging from officials at the Lincoln Museum to parks department employees, about Oldroyd in the past but always got a cool reception to my querie.

Lastly, my wife treated me to a birthday trip to Springfield, Illinois in July. I traveled to the Lincoln home on an early Saturday morning to reflect while seated in front of the Lincoln home. Based on trips past, I’ve learned that the early morning hours are best. No school buses, tourists or fitness walkers/bikers to mar the scene. I have been coming to Springfield for many years. Of course, Abraham Lincoln is the reason for my visit. However, I never forget that Osborn Oldroyd lived in the house and operated his museum here for nearly a decade (1884-93). I’d asked several people, ranging from officials at the Lincoln Museum to parks department employees, about Oldroyd in the past but always got a cool reception to my querie.

On this latest visit, I wandered over to the interpretive marker directly across the street and facing the Lincoln home. Much to my amazement, there he was. The newly placed plaque is dedicated to Osborn Oldroyd’s museum once housed there. I could not believe my eyes! At last, Oldroyd has received official recognition from the powers that be in Lincoln’s Springfield. Maybe things are looking up for Captain Oldroyd after all. I doubt that I’ll ever be prouder of a historical pursuit than I was that morning.

Original publish date: July 20, 2017

Original publish date: July 20, 2017 Another of the letters, dated Dec. 10, 1902, touched me personally because it was written by the sister of Louis Weichmann, the main government witness at the trial of the conspirators. Weichmann lived in Mrs. Surratt’s boarding house and many believe it was Weichmann’s testimony that got Mary Surratt hung. Weichmann moved to Anderson Indiana after the trial and founded Anderson business college. He is buried in Anderson’s St. Francis cemetery in an unmarked grave. “Dear Sir-I am sending you a copy of Sunday’s Indianapolis Journal containing a confession of one of the conspirators of President Lincoln….With best regards from our family, I remain Sincerely yours, Mrs. C.O. Crowley Sister of the late L.J. Wiechmann.” Curiously, Mrs. Crowley misspelled her own maiden name in her letter.

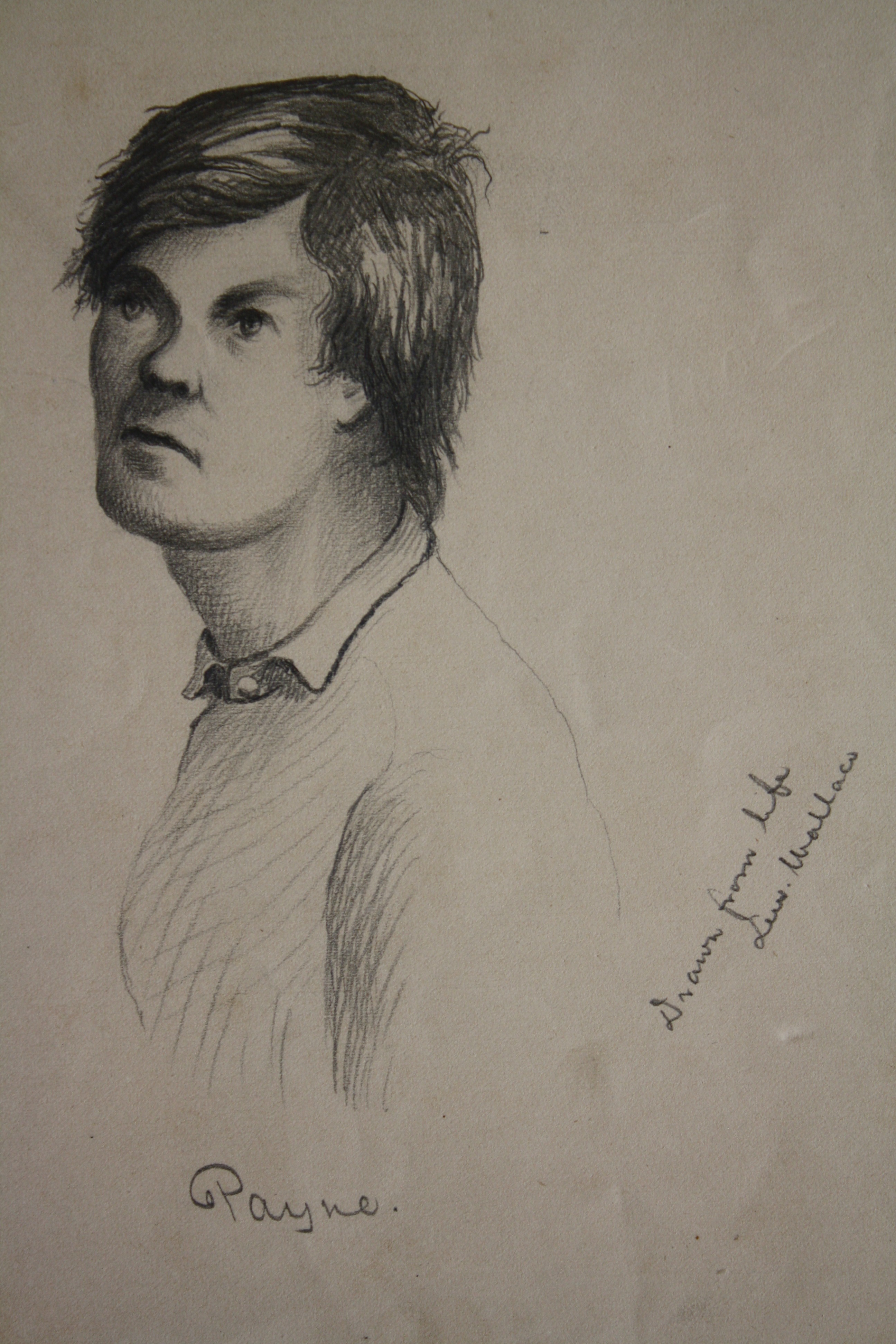

Another of the letters, dated Dec. 10, 1902, touched me personally because it was written by the sister of Louis Weichmann, the main government witness at the trial of the conspirators. Weichmann lived in Mrs. Surratt’s boarding house and many believe it was Weichmann’s testimony that got Mary Surratt hung. Weichmann moved to Anderson Indiana after the trial and founded Anderson business college. He is buried in Anderson’s St. Francis cemetery in an unmarked grave. “Dear Sir-I am sending you a copy of Sunday’s Indianapolis Journal containing a confession of one of the conspirators of President Lincoln….With best regards from our family, I remain Sincerely yours, Mrs. C.O. Crowley Sister of the late L.J. Wiechmann.” Curiously, Mrs. Crowley misspelled her own maiden name in her letter. Included within that collection was a group of several dozen items that once belonged to Osborn Oldroyd himself. This included correspondence from Anderson’s Louis Weichmann to Oldroyd about shared information for books about Abraham Lincoln both men were simultaneously working on as well as photos and several handwritten eyewitness accounts of the assassination of President Lincoln. My personal favorite was a pencil drawing of Lincoln Conspirator Lewis Thornton Powell drawn by Crawfordsville, Indiana’s General Lew Wallace.

Included within that collection was a group of several dozen items that once belonged to Osborn Oldroyd himself. This included correspondence from Anderson’s Louis Weichmann to Oldroyd about shared information for books about Abraham Lincoln both men were simultaneously working on as well as photos and several handwritten eyewitness accounts of the assassination of President Lincoln. My personal favorite was a pencil drawing of Lincoln Conspirator Lewis Thornton Powell drawn by Crawfordsville, Indiana’s General Lew Wallace. Original publish date: July 13, 2017

Original publish date: July 13, 2017 Ironically, the same year that Oldroyd moved to the Peterson house, Ford’s Theatre, where John Wilkes Booth had shot Abraham Lincoln, collapsed. The building closed since the President’s death, operated as an office until June 9, 1893, when the interior of the historic building collapsed. Twenty-two clerks died in the tragedy and sixty-eight others were seriously injured. Within a year the damage was repaired and the former theatre was remodeled for use as a government warehouse.

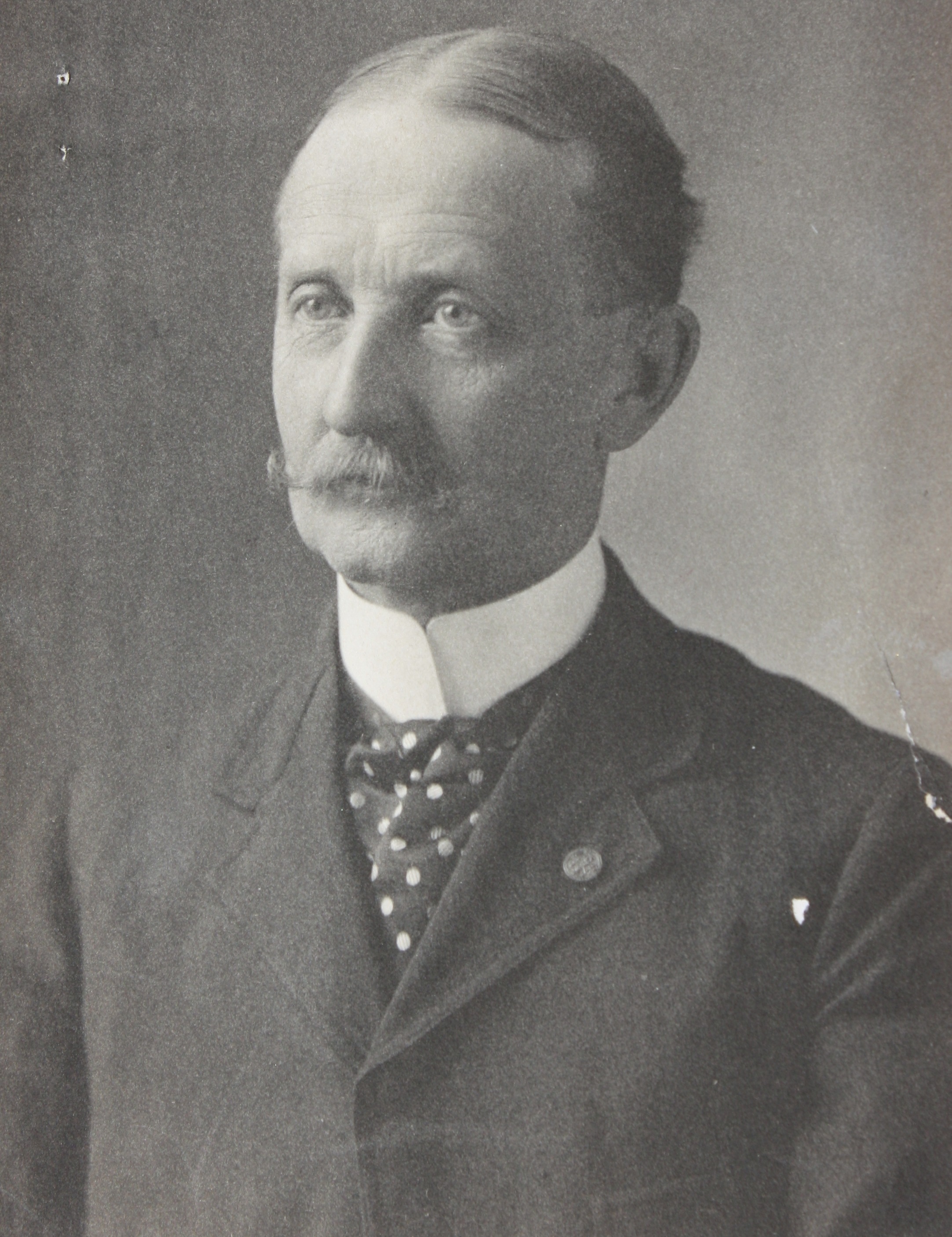

Ironically, the same year that Oldroyd moved to the Peterson house, Ford’s Theatre, where John Wilkes Booth had shot Abraham Lincoln, collapsed. The building closed since the President’s death, operated as an office until June 9, 1893, when the interior of the historic building collapsed. Twenty-two clerks died in the tragedy and sixty-eight others were seriously injured. Within a year the damage was repaired and the former theatre was remodeled for use as a government warehouse. The May 2, 1926, Washington Post announced the purchase with a banner headline reading, “Gets Storehouse of Lincoln Relics: Government Action Assures Preservation of Oldroyd Collection Here.” The newspaper column reported, “Captain Oldroyd has been gathering the collection for 63 years, having started on this patriotic work of love for his chieftain soon after he was released from service in the internecine strife (Civil War). Mr. Oldroyd is now 80 years old. Having for years been a student of Lincoln, acting as a guide for his collection all through its formation, Capt. Oldroyd has become a rich source of Lincoln traditions. Passage by Congress of the measure authorizing the purchase of the Oldroyd collection, 3, 000 authentic Lincoln mementos now on display in the historic Petersen House where the martyred president died, will preserve for future generations making pilgrimages to Washington a great storehouse of materials identified with Lincoln tradition.”

The May 2, 1926, Washington Post announced the purchase with a banner headline reading, “Gets Storehouse of Lincoln Relics: Government Action Assures Preservation of Oldroyd Collection Here.” The newspaper column reported, “Captain Oldroyd has been gathering the collection for 63 years, having started on this patriotic work of love for his chieftain soon after he was released from service in the internecine strife (Civil War). Mr. Oldroyd is now 80 years old. Having for years been a student of Lincoln, acting as a guide for his collection all through its formation, Capt. Oldroyd has become a rich source of Lincoln traditions. Passage by Congress of the measure authorizing the purchase of the Oldroyd collection, 3, 000 authentic Lincoln mementos now on display in the historic Petersen House where the martyred president died, will preserve for future generations making pilgrimages to Washington a great storehouse of materials identified with Lincoln tradition.” What became of the pilfered Lincoln home artifacts? During a near forty year period between the 1950s and late 1980s, the Lincoln Home got back the disputed 25 items from Ford’s Theater that Oldroyd had allegedly removed without permission. “The items were well preserved. For the most part, these were all utilitarian items that might have been used every day by the residents of the home during the years before preservation became a priority.” says curator Cornelius “An argument could be made that if not for Osborn Oldroyd, these items might have been lost forever.”

What became of the pilfered Lincoln home artifacts? During a near forty year period between the 1950s and late 1980s, the Lincoln Home got back the disputed 25 items from Ford’s Theater that Oldroyd had allegedly removed without permission. “The items were well preserved. For the most part, these were all utilitarian items that might have been used every day by the residents of the home during the years before preservation became a priority.” says curator Cornelius “An argument could be made that if not for Osborn Oldroyd, these items might have been lost forever.” Original publish date: July 6, 2017

Original publish date: July 6, 2017 During his early years in Springfield, he ran a succession of failed businesses. All the while, Oldroyd was moving his family ever closer to the Lincoln Home at Eighth and Jackson Streets. The Oldroyd family first lived at 1101 South Seventh, then 500 South Eighth Street (immediately south of the home), and then, in 1883, when the Lincoln Home became available to rent, Oldroyd moved his family in before the last occupants had completely moved out. At that time, Lincoln’s only surviving son, Robert, owned the home and reluctantly charged Oldroyd $25 per month rent. Contemporary accounts claim that Robert Todd Lincoln agreed to the idea of a museum as long as it was free to the public, a stipulation in place to this day.

During his early years in Springfield, he ran a succession of failed businesses. All the while, Oldroyd was moving his family ever closer to the Lincoln Home at Eighth and Jackson Streets. The Oldroyd family first lived at 1101 South Seventh, then 500 South Eighth Street (immediately south of the home), and then, in 1883, when the Lincoln Home became available to rent, Oldroyd moved his family in before the last occupants had completely moved out. At that time, Lincoln’s only surviving son, Robert, owned the home and reluctantly charged Oldroyd $25 per month rent. Contemporary accounts claim that Robert Todd Lincoln agreed to the idea of a museum as long as it was free to the public, a stipulation in place to this day.

For the next five years “Captain” Oldroyd kept the Lincoln Home and added to his Lincoln collection. At one point, reports claim that Robert Lincoln was furious when Oldroyd allegedly displayed a photograph of John Wilkes Booth in the home, reportedly on the fireplace mantle. Some sources claim that Robert protested and in 1893, when the Illinois state political tides shifted, Oldroyd was unceremoniously ousted as custodian. The new governor put one of his own men into Oldroyd’s former position as political patronage.

For the next five years “Captain” Oldroyd kept the Lincoln Home and added to his Lincoln collection. At one point, reports claim that Robert Lincoln was furious when Oldroyd allegedly displayed a photograph of John Wilkes Booth in the home, reportedly on the fireplace mantle. Some sources claim that Robert protested and in 1893, when the Illinois state political tides shifted, Oldroyd was unceremoniously ousted as custodian. The new governor put one of his own men into Oldroyd’s former position as political patronage.