Original publish date: December 19, 2010

Reissue date: December 19, 2019

Last week I wrote of Irvington namesake Washington Irving’s connection to the author most associated with the Victorian Era, Charles Dickens. While nearly everyone is familiar with Dickens classic seasonal ghost story, “A Christmas Carol”, not many have experienced the magic of a Washington Irving Christmas tale. Although Irving lived a portion of his life as a European vagabond meticulously chronicling the customs, traditions and lore that was fast fading away from the centuries old landscape, he is best remembered today for his American folklore stories like Rip Van Winkle and Ichabod Crane.

For decades, Irving’s description of traditional English Christmas celebrations that influenced nearly every author that came after him were thought to have been formulated and influenced by parties and gatherings he had personally attended. However, its closer to the truth to say that Irving’s Christmas stories were not solely based on any holiday celebration he had attended, but rather many were accounts intentionally created by the imagination of Irving himself. In other words, Washington Irving’s masterful prose influenced generations of experts and historians through the power of his superior skill of embellishment.

In 1808, Irving created an updated version of Old St. Nick that rode over the treetops in a horse-drawn wagon “dropping gifts down the chimneys of his favorites.” Irving described Santa as a jolly Dutchman who smoked a long-stemmed clay pipe and wore baggy breeches and a broad-brimmed hat. Irving’s work also included the familiar phrase, “laying a finger beside his nose” some 14 years before a Troy, New York newspaper published the iconic children’s poem “Twas the night before Christmas,” which turned Santa’s wagon into a sleigh powered by reindeer.

In 1808, Irving created an updated version of Old St. Nick that rode over the treetops in a horse-drawn wagon “dropping gifts down the chimneys of his favorites.” Irving described Santa as a jolly Dutchman who smoked a long-stemmed clay pipe and wore baggy breeches and a broad-brimmed hat. Irving’s work also included the familiar phrase, “laying a finger beside his nose” some 14 years before a Troy, New York newspaper published the iconic children’s poem “Twas the night before Christmas,” which turned Santa’s wagon into a sleigh powered by reindeer.

Irving describes St. Nicholas’ holiday activities by saying, “At this early period was instituted that pious ceremony, still religiously observed in all our ancient families of the right breed, of hanging up a stocking in the chimney on St. Nicholas eve; which stocking is always found in the morning miraculously filled; for the good St. Nicholas has ever been a great giver of gifts, particularly to children.” These descriptions were first published as observances of New York’s old Dutch tradition. His “Old Christmas” tales, first published in 1820, are among the earliest popular accounts of 19th century English Christmas customs, many of which would soon be adopted in the United States and remain familiar to us today.

Irving’s stories are full of mistletoe and evergreen wreaths, Christmas candles and blazing Yule logs, singing and dancing, carolers at the door and the preacher at the church, wine and wassail, and, of course, the festive Christmas dinner. The description of Old Christmas as Irving experienced it in “Merrie Olde England,” helped to popularize these traditions in his native land.

Irving’s stories are full of mistletoe and evergreen wreaths, Christmas candles and blazing Yule logs, singing and dancing, carolers at the door and the preacher at the church, wine and wassail, and, of course, the festive Christmas dinner. The description of Old Christmas as Irving experienced it in “Merrie Olde England,” helped to popularize these traditions in his native land.

The modern day reader might not realize it but Irving’s descriptions of his own Christmas vision were a subtle form of protest. In an era when our new nation was busy finding its own footing, barely two decades after the writing of the American Constitution, Irving’s first formations of the “New” Christmas were created in an attempt to pull the religious holiday away from the churches and government buildings and take it back where he felt it belonged, with the people. Irving describes it thusly, “Even the poorest cottage welcomed the festive season with green decorations of bay and holly…the cheerful fire glanced its rays through the lattice, inviting the passenger to raise the latch, and join the gossip knot huddled around the hearth, beguiling the long evening with legendary jokes and oft-told Christmas tales.” Irving, ever the bard, also wrote, “At Christmas be merry, and thankful withal. And feast thy poor neighbours, the great and the small.”

Irving’s work was our fledgling country’s first introduction to Christmas tradition and, although many of them survive to the present day, some have morphed into modern versions slightly different from those described by Washington Irving. The mistletoe is still hung in farmhouses and kitchens at Christmas; and the young men have the privilege of kissing the girls under it, plucking each time a berry from the bush. When the berries are all plucked, the privilege ceases.

The Yule-log is a great log of wood, sometimes the root of a tree, brought into the house on Christmas eve, laid in the fireplace, and lighted with a piece of last year’s log. While it burned there was great drinking, singing, and telling of tales. The Yule-log was to burn all night; if it went out, it was considered bad luck. If a squinting person come to the house while it was burning, or a barefooted person, it was considered bad luck. A piece of the Yule-log was carefully put away to light the next year’s Christmas fire.

The Yule-log is a great log of wood, sometimes the root of a tree, brought into the house on Christmas eve, laid in the fireplace, and lighted with a piece of last year’s log. While it burned there was great drinking, singing, and telling of tales. The Yule-log was to burn all night; if it went out, it was considered bad luck. If a squinting person come to the house while it was burning, or a barefooted person, it was considered bad luck. A piece of the Yule-log was carefully put away to light the next year’s Christmas fire.

Washington Irving profoundly influenced the modern day American Christmas in two distinct ways. First, his reinvention of jolly St. Nick into a gift toting ambassador gave hope to every child across the land. Second, the timing of the Christmas holiday during an other wise bleak wintry season offered an emotional waymark to a cabin-fever populace, both young and old. Within a decade of the publication of Irving’s Christmas “Sketch Book,” Americans were greeting each other with “Merry Christmas” wishes, and stores on main streets across America extended their hours to accommodate holiday shoppers.

So remember, this Christmas weekend, as you gather together with friends, loved ones and family to celebrate holiday traditions, think of Washington Irving, America’s Father Christmas.

Dickens’s memorable descriptions of Christmas scenes in “A Christmas Carol” owe a great deal to Irving. In February of 1842, while attending a New York dinner hosted by Irving, Dickens amusingly revealed his devotion to the great American author when he rose his glass in a toast and said, “I say, gentlemen, I do not go to bed two nights out of seven without taking Washington Irving under my arm upstairs to bed with me.”

Dickens’s memorable descriptions of Christmas scenes in “A Christmas Carol” owe a great deal to Irving. In February of 1842, while attending a New York dinner hosted by Irving, Dickens amusingly revealed his devotion to the great American author when he rose his glass in a toast and said, “I say, gentlemen, I do not go to bed two nights out of seven without taking Washington Irving under my arm upstairs to bed with me.” Irving’s descriptions of the short and cold winter days in his story “Old Christmas” make their way into the moral landscape lacking in Scrooge’s character in Dickens “A Christmas Carol”: “In the depth of winter, when nature lies despoiled of every charm, and wrapped in her shroud of sheeted snow, we turn for our gratifications to moral sources. The dreariness and desolation of the landscape, the short gloomy days and darksome nights, while they circumscribe our wanderings, shut in our feelings also from rambling abroad, and make us more keenly disposed for the pleasures of the social circle. Our thoughts are more concentrated; our friendly sympathies more aroused. We feel more sensibly the charm of each other’s society, and are brought more closely together by dependence upon each other for enjoyment. Heart calleth unto heart; and we draw our pleasures from the deep wells of living kindness, which lie in the quiet recesses of our bosoms; and which, when resorted to, furnish forth the pure element of domestic felicity.”

Irving’s descriptions of the short and cold winter days in his story “Old Christmas” make their way into the moral landscape lacking in Scrooge’s character in Dickens “A Christmas Carol”: “In the depth of winter, when nature lies despoiled of every charm, and wrapped in her shroud of sheeted snow, we turn for our gratifications to moral sources. The dreariness and desolation of the landscape, the short gloomy days and darksome nights, while they circumscribe our wanderings, shut in our feelings also from rambling abroad, and make us more keenly disposed for the pleasures of the social circle. Our thoughts are more concentrated; our friendly sympathies more aroused. We feel more sensibly the charm of each other’s society, and are brought more closely together by dependence upon each other for enjoyment. Heart calleth unto heart; and we draw our pleasures from the deep wells of living kindness, which lie in the quiet recesses of our bosoms; and which, when resorted to, furnish forth the pure element of domestic felicity.” Dickens Washington Irving inspired story popularized the phrase “Merry Christmas” and introduced the name ‘Scrooge’ and exclamation ‘Bah! Humbug!’ to the English language. However the book’s legacy is the powerful influence it has exerted upon its readers. A Christmas Carol” is widely credited with the “Spirit” of charitable giving associated so closely with the holiday today. Victorian Era examples can be found many places; in 1874, “Treasure Island” author Robert Louis Stevenson vowed to give generously after reading Dickens’s Christmas book, a Boston, Massachusetts merchant, expressed his generous hospitality by hosting two Christmas dinners after attending a reading of the book on Christmas Eve in 1867, and was so moved he closed his factory on Christmas Day and sent every employee a turkey and in 1901, the Queen of Norway sent gifts to London’s crippled children signed “With Tiny Tim’s Love.”

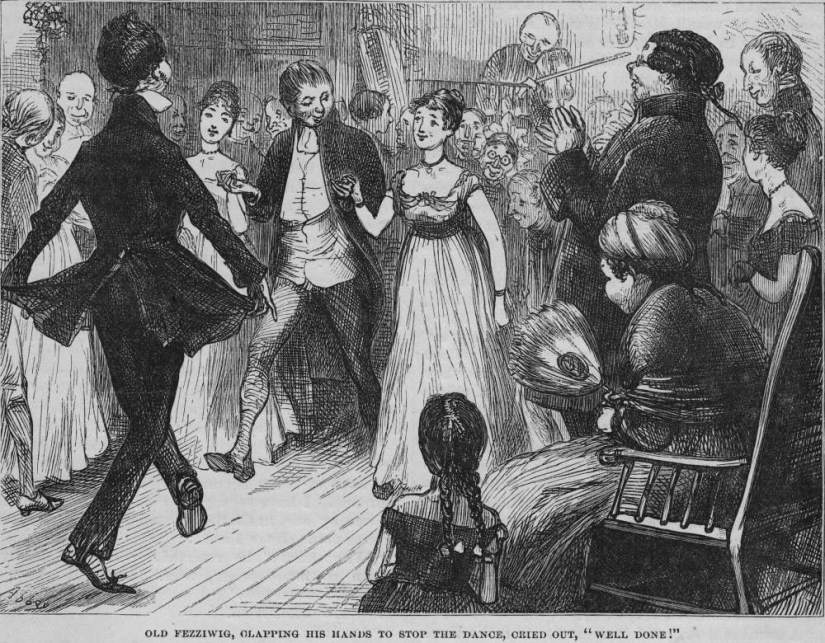

Dickens Washington Irving inspired story popularized the phrase “Merry Christmas” and introduced the name ‘Scrooge’ and exclamation ‘Bah! Humbug!’ to the English language. However the book’s legacy is the powerful influence it has exerted upon its readers. A Christmas Carol” is widely credited with the “Spirit” of charitable giving associated so closely with the holiday today. Victorian Era examples can be found many places; in 1874, “Treasure Island” author Robert Louis Stevenson vowed to give generously after reading Dickens’s Christmas book, a Boston, Massachusetts merchant, expressed his generous hospitality by hosting two Christmas dinners after attending a reading of the book on Christmas Eve in 1867, and was so moved he closed his factory on Christmas Day and sent every employee a turkey and in 1901, the Queen of Norway sent gifts to London’s crippled children signed “With Tiny Tim’s Love.” Speaking solely for myself, I often find myself drawing upon Dickens description of Old Fezziwig when I think of how others may observe me. In the novel, the Ghost of Christmas Past conjures up the memory of Scrooge’s old employer, Mr. Fezziwig, who converts his warehouse into a festive hall in which to celebrate Christmas: “Clear away. There is nothing they [Fezziwig’s employees] wouldn’t have cleared away, with old Fezziwig looking on. It was done in a minute. Every movable was packed off, as if it were dismissed from public life for evermore; the floor was swept and watered, the lamps were trimmed, fuel was heaped upon the fire; and the warehouse was as snug, and warm, and dry, and bright a ball-room, as you would desire to see upon a winter’s night.” Thus the ledger books, the daily grind, and the cold give way to music, dance, games, food, and fellowship.

Speaking solely for myself, I often find myself drawing upon Dickens description of Old Fezziwig when I think of how others may observe me. In the novel, the Ghost of Christmas Past conjures up the memory of Scrooge’s old employer, Mr. Fezziwig, who converts his warehouse into a festive hall in which to celebrate Christmas: “Clear away. There is nothing they [Fezziwig’s employees] wouldn’t have cleared away, with old Fezziwig looking on. It was done in a minute. Every movable was packed off, as if it were dismissed from public life for evermore; the floor was swept and watered, the lamps were trimmed, fuel was heaped upon the fire; and the warehouse was as snug, and warm, and dry, and bright a ball-room, as you would desire to see upon a winter’s night.” Thus the ledger books, the daily grind, and the cold give way to music, dance, games, food, and fellowship.

The charities involved are the Diabetes Youth Foundation summer camp in Noblesville, Helping Paws Pet Rescue and The PourHouse Street Outreach Center. The Black Hat Society hopes to raise $ 10,000 for these worthy charities. In addition, there will be a donation box placed at the entrance of the Irving Theatre during the event. The Black Hat Society requests donations of men’s socks, pet food and cleaning supplies, all of which are in almost constant need by these institutions. Karin informs me that Eric Wilson at Irvington Insurance has helped mightily in spearheading the group’s donation efforts.

The charities involved are the Diabetes Youth Foundation summer camp in Noblesville, Helping Paws Pet Rescue and The PourHouse Street Outreach Center. The Black Hat Society hopes to raise $ 10,000 for these worthy charities. In addition, there will be a donation box placed at the entrance of the Irving Theatre during the event. The Black Hat Society requests donations of men’s socks, pet food and cleaning supplies, all of which are in almost constant need by these institutions. Karin informs me that Eric Wilson at Irvington Insurance has helped mightily in spearheading the group’s donation efforts. From there, the Black Hat Society marched in the Indy St. Patrick’s Day parade, Pride parade and they recently won a $ 100 prize in a parade in Fountain Square. Should you miss the releases party, never fear, the witches will have their calendars for sale at their booth at the Halloween Festival. The calendars can be ordered on line at theblackhatsociety.org and on their facebook page.

From there, the Black Hat Society marched in the Indy St. Patrick’s Day parade, Pride parade and they recently won a $ 100 prize in a parade in Fountain Square. Should you miss the releases party, never fear, the witches will have their calendars for sale at their booth at the Halloween Festival. The calendars can be ordered on line at theblackhatsociety.org and on their facebook page.

When I asked Craig what it is like to be a male witch surrounded by so many women, he answered succinctly, “It’s lonely.” Craig would like to see more guys join the group. “At last year’s St. Patrick’s Day Parade, I made eight drums for our drum line, but we only had 4 drummers. We need more guys!” Craig is amazed by just how generous the witches in the Black Hat Society are, “If I need something for a prop or help in building a set, I get 30 or 40 responses within minutes.”

When I asked Craig what it is like to be a male witch surrounded by so many women, he answered succinctly, “It’s lonely.” Craig would like to see more guys join the group. “At last year’s St. Patrick’s Day Parade, I made eight drums for our drum line, but we only had 4 drummers. We need more guys!” Craig is amazed by just how generous the witches in the Black Hat Society are, “If I need something for a prop or help in building a set, I get 30 or 40 responses within minutes.”

The Band was born only after the near fatal motorcycle accident involving the world’s most famous electric folksinger changed their direction. And, although The Band’s first album “Music From Big Pink” debuted on July 1st, 1968, the band from West Saugerties, New York did not perform live until the spring of 1969 a continent away in San Francisco. The album was created start to finish in two weeks time with no overdubbing, unheard of for its day. What’s more, The Band very nearly didn’t take the stage at all; saved only after legendary promoter Bill Graham picked a hypnotist out of a bay area phonebook to right the ship. The little-known stories of these great incidents will be discussed this Saturday.

The Band was born only after the near fatal motorcycle accident involving the world’s most famous electric folksinger changed their direction. And, although The Band’s first album “Music From Big Pink” debuted on July 1st, 1968, the band from West Saugerties, New York did not perform live until the spring of 1969 a continent away in San Francisco. The album was created start to finish in two weeks time with no overdubbing, unheard of for its day. What’s more, The Band very nearly didn’t take the stage at all; saved only after legendary promoter Bill Graham picked a hypnotist out of a bay area phonebook to right the ship. The little-known stories of these great incidents will be discussed this Saturday. To understand The Band, one must also understand the era into which it was born. Big Pink’s 1968 debut was also the year of student protests against the Vietnam War, Martin Luther King and Robert F Kennedy’s assassination, riots at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Black Panther demonstrations, feminists protesting the Miss America pageant in Atlantic City, Apollo 7 and 8’s moon landing rehearsal flights, Charles Manson gathering his cult members at Spahn Ranch and Nixon’s nomination for president. To many, America was coming apart at the seams and the divide between generations had never seemed wider. This band, formed out of a classically trained musician, a teenaged alcoholic, a butche’rs apprentice, a Jewish Native American grifter and a veteran performer from the Mississippi Delta, stepped forward to bridge the gap.

To understand The Band, one must also understand the era into which it was born. Big Pink’s 1968 debut was also the year of student protests against the Vietnam War, Martin Luther King and Robert F Kennedy’s assassination, riots at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Black Panther demonstrations, feminists protesting the Miss America pageant in Atlantic City, Apollo 7 and 8’s moon landing rehearsal flights, Charles Manson gathering his cult members at Spahn Ranch and Nixon’s nomination for president. To many, America was coming apart at the seams and the divide between generations had never seemed wider. This band, formed out of a classically trained musician, a teenaged alcoholic, a butche’rs apprentice, a Jewish Native American grifter and a veteran performer from the Mississippi Delta, stepped forward to bridge the gap. While considered the fathers of the history conscious “Americana” music movement, make no mistake about it, these guys were quintessential rock and rollers. Fast cars, fast women, and fast times punctuated the lives of each member of The Band. They started in the age of rockabilly, while Elvis Presley was still shaking things, up and finished at the dawn of hip-hop. They crossed paths with Hollywood movie stars, gangsters and presidents. Eric Clapton, Van Morrison, Dr. John, Sonny Boy Williamson, Muddy Waters, Conway Twitty, Tiny Tim, Jack Ruby, Martin Scorsese and Jimmy Carter all play a part in the story of these four Canadians and one self-described “cracker” from Arkansas to create a mystique that still surrounds them today, long after three out of the five band members have passed.

While considered the fathers of the history conscious “Americana” music movement, make no mistake about it, these guys were quintessential rock and rollers. Fast cars, fast women, and fast times punctuated the lives of each member of The Band. They started in the age of rockabilly, while Elvis Presley was still shaking things, up and finished at the dawn of hip-hop. They crossed paths with Hollywood movie stars, gangsters and presidents. Eric Clapton, Van Morrison, Dr. John, Sonny Boy Williamson, Muddy Waters, Conway Twitty, Tiny Tim, Jack Ruby, Martin Scorsese and Jimmy Carter all play a part in the story of these four Canadians and one self-described “cracker” from Arkansas to create a mystique that still surrounds them today, long after three out of the five band members have passed.