Original publish date: June 15, 2015

Reissue date: April 25, 2019

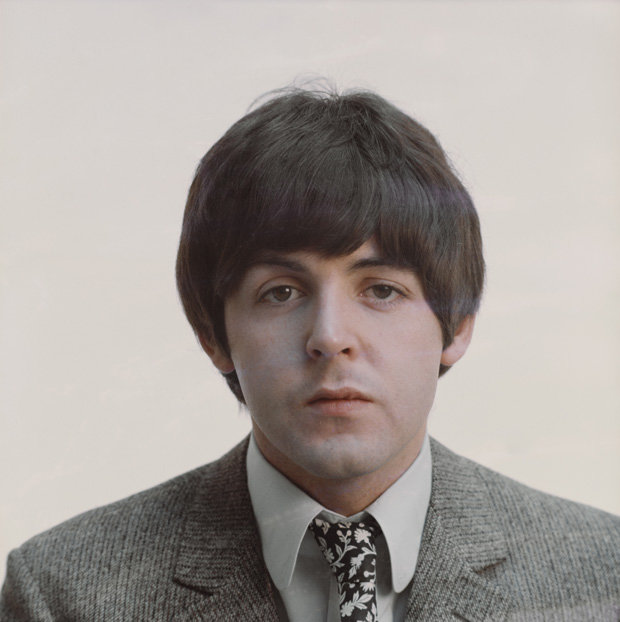

Last week, we revisited the famous “Paul is Dead” rumor swirling around the Beatles rock band during the last few years of the turbulent sixties decade. The rumor that Paul McCartney died in a November 1966 car crash seems silly to us now, but it was pervasive back in the day. As we covered in Part I of this series, the album “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” was released in June of 1967 to much well deserved fanfare. Both for the music it contained and the supposed references it made to the death of the Beatles’ heartthrob bass player.

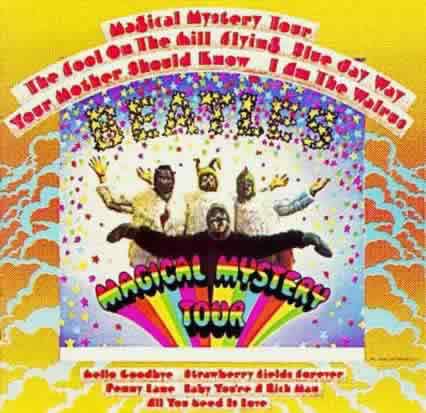

Magical Mystery Tour was released on December 8, 1967. After the success of Sgt. Pepper’s, Paul McCartney wanted to create a film based upon The Beatles and their music. The film was to be unscripted and would “star” various “ordinary” people who were to travel the countryside on a bus and experience “magical” adventures on film. The Magical Mystery Tour film was made and included six new Beatles songs. The film was universally panned and largely forgotten, but the resulting album / soundtrack is considered a classic. Produced by George Martin, Magical Mystery Tour was packaged by Capitol records as a full LP with a 24-page companion picture booklet.

Magical Mystery Tour was released on December 8, 1967. After the success of Sgt. Pepper’s, Paul McCartney wanted to create a film based upon The Beatles and their music. The film was to be unscripted and would “star” various “ordinary” people who were to travel the countryside on a bus and experience “magical” adventures on film. The Magical Mystery Tour film was made and included six new Beatles songs. The film was universally panned and largely forgotten, but the resulting album / soundtrack is considered a classic. Produced by George Martin, Magical Mystery Tour was packaged by Capitol records as a full LP with a 24-page companion picture booklet.

The booklet was eagerly devoured by the “Paul is dead” theorists and the clues it supposedly offered only fueled the ever-growing conspiracy. So, dear readers go and dust off your copies of Magical Mystery tour as we thumb through it and decipher the clues. On page 3 of the booklet, Paul is dressed in a British military uniform posed seated behind a desk with a nameplate that reads “I Was” in front of him. Further interpretations of the nameplate claim it reads either “I You Was” or “I Was You,” both suggesting that Paul had disappeared and been replaced by a double. Also, the British Union Jack flags behind Paul are crossed as they would traditionally appear at a military funeral.

On page 6, John Lennon appears as a carnival barker manning a ticket booth with a sign reading: “The best way to go is by M&D Co.” According to the “Paul is dead” rumor, M&D Co. was a funeral parlor, but such a place never existed. Theorists also note that in the picture, a departure time is given but the return time is blank.

On page 9, “Fool on the Hill” is shown next to a cartoon image of Paul who appears to be standing on a grave shaped mound of grass. The second “L” in the title extends above Paul’s head and dribbles into his scalp as though his head were split open. This picture hints at the devastating head injury that Paul allegedly sustained in his fatal accident.

In the band photos on pages 10, 11 and 12, Paul appears without shoes, which would become a recurring theme among the “Paul is Dead” crowd in years to come. Also, on Ringo’s bass drum between the word “Love” and the name “The Beatles”, the numeral “3” can plainly be seen which seems to spell out the cryptic phrase “Love the 3 Beatles”. Eerily, in that same photo, blood appears to be dripping from Paul’s shoes resting next to the drum. Theorists assert that “empty shoes were a Grecian symbol of death.”

On page 23, the Beatles are all wearing stark white tuxedos with carnations in the lapels. Paul’s flower is black while the other Beatles have red flowers. Years later, Paul denied that the black carnation had any significance at all; “I was wearing a black flower because they ran out of red ones.”

On page 23, the Beatles are all wearing stark white tuxedos with carnations in the lapels. Paul’s flower is black while the other Beatles have red flowers. Years later, Paul denied that the black carnation had any significance at all; “I was wearing a black flower because they ran out of red ones.”

And on the final page of the photo booklet, once again, a hand appears over Paul’s head. Although this instance of a hand over Paul’s head isn’t nearly as dramatic as the Sgt. Pepper’s cover photo because several people have their hands raised above their heads in this picture. But it certainly did nothing to ease the conspiracies.

And on the final page of the photo booklet, once again, a hand appears over Paul’s head. Although this instance of a hand over Paul’s head isn’t nearly as dramatic as the Sgt. Pepper’s cover photo because several people have their hands raised above their heads in this picture. But it certainly did nothing to ease the conspiracies.

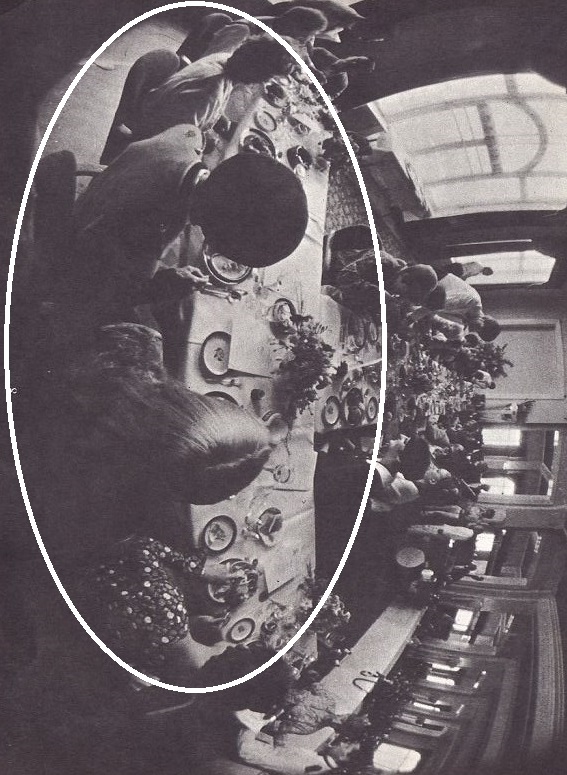

However, there is one compelling image in the pages of the pictorial book that, when analyzed, virtually screamed out to all those looking for signs of death in the Beatles’ works to substantiate the rumors of Paul’s premature passing. On page 8 of the booklet, a dining scene, at the left of the image (but on the right as the image is rotated one turn clockwise), with a little imagination, you can see a skull in this picture. It occupies the left side of the picture, with the beret of the person seated at the table forming the eye and the hair of the woman seated next to him the mouth. Like a “Magic Eye” painting, once you’ve accepted it as a skull, it’s easy to see the damage to the top of the head. This grisly image suggests the damage to Paul’s head as a result of his car crash. The fact that this picture, unlike all of the other images in the booklet, does not appear in the movie again only encouraged the “Paul is Dead” crowd as proof of his passing.

However, there is one compelling image in the pages of the pictorial book that, when analyzed, virtually screamed out to all those looking for signs of death in the Beatles’ works to substantiate the rumors of Paul’s premature passing. On page 8 of the booklet, a dining scene, at the left of the image (but on the right as the image is rotated one turn clockwise), with a little imagination, you can see a skull in this picture. It occupies the left side of the picture, with the beret of the person seated at the table forming the eye and the hair of the woman seated next to him the mouth. Like a “Magic Eye” painting, once you’ve accepted it as a skull, it’s easy to see the damage to the top of the head. This grisly image suggests the damage to Paul’s head as a result of his car crash. The fact that this picture, unlike all of the other images in the booklet, does not appear in the movie again only encouraged the “Paul is Dead” crowd as proof of his passing.

Then there’s the cover image. The bandmates appear on the cover, as they did in the companion film, dressed in outlandish animal costumes. The animal costumes were in keeping with the predominantly psychedelic themes of the music on the LP. It’s a common misconception that Paul was the walrus, no doubt made famous by the lyric in Glass Onion on “The White Album” and the song’s innumerable references to it in the ‘Paul is Dead’ conspiracy. However, Paul isn’t the walrus, John is. This can be seen in the ‘I Am The Walrus’ segment of the Magical Mystery Tour film where the walrus is seated at the piano singing the song (just as John was at the start of the song). The hippo is standing in front playing left-handed bass guitar. In truth, Paul was the Hippo, John was the Walrus, George was the Rabbit and Ringo was the Chicken.

Theorists would claim a connection between Paul’s supposed Walrus costume and the death rumor, but the real controversy revolved around the word “Beatles” above the lad’s heads that purportedly reveal a secret phone number. As Rolling Stone famously pointed out, it’s not exactly clear what that phone number is supposed to be. Depending on whom you ask it could be read as “231-7438, 834-7135, 536-0195, 510-6643, 546-3663, 624-7125, no telling what city, maybe London.” If you turn the album cover upside down and hold it in front of a mirror you can see the numbers 8341735, which is a stretch because the threes, the seven and the five are backwards. If you simply hold the album cover upside-down, the numbers could be 5371438. Of course, there is no area code. The rumor claimed that when this number was dialed, the caller would receive information about Paul’s death, or the person would be able to take a trip to “Magical Beatle Mystery Island”, or maybe even speak to Paul in the hereafter. Stories circulated about the strange responses callers were receiving from the voices on the other end of the phone line. Later it was discovered that one of the phone numbers belonged to a journalist who was nearly driven crazy by the numerous phone calls from people hoping to connect with the late Paul McCartney.

Theorists would claim a connection between Paul’s supposed Walrus costume and the death rumor, but the real controversy revolved around the word “Beatles” above the lad’s heads that purportedly reveal a secret phone number. As Rolling Stone famously pointed out, it’s not exactly clear what that phone number is supposed to be. Depending on whom you ask it could be read as “231-7438, 834-7135, 536-0195, 510-6643, 546-3663, 624-7125, no telling what city, maybe London.” If you turn the album cover upside down and hold it in front of a mirror you can see the numbers 8341735, which is a stretch because the threes, the seven and the five are backwards. If you simply hold the album cover upside-down, the numbers could be 5371438. Of course, there is no area code. The rumor claimed that when this number was dialed, the caller would receive information about Paul’s death, or the person would be able to take a trip to “Magical Beatle Mystery Island”, or maybe even speak to Paul in the hereafter. Stories circulated about the strange responses callers were receiving from the voices on the other end of the phone line. Later it was discovered that one of the phone numbers belonged to a journalist who was nearly driven crazy by the numerous phone calls from people hoping to connect with the late Paul McCartney.

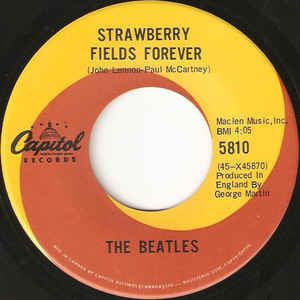

But it was the music contained on the album that offered the clue seekers the most tantalizing hints at Paul’s demise. One of the best known “Paul is dead” audio clues comes at the end of “Strawberry Fields Forever”. As the song fades out for the second time, John allegedly says “I buried Paul.”‘ This audio clue can be heard more clearly when the record is played at 45 rpm as John’s voice is slowed down to a virtual crawl. Years later, John admitted that he was really saying “cranberry sauce,” which became evident on the “take 7 and edit piece” version of the song that appeared on Anthology II in 1996. Paul explained “That’s John’s humor. John would say something totally out of sync, like ‘cranberry sauce.’ If you don’t realize that John’s apt to say something like ‘cranberry sauce’ when he feels like it, then you start to hear a funny little word there, and you think aha!”

But it was the music contained on the album that offered the clue seekers the most tantalizing hints at Paul’s demise. One of the best known “Paul is dead” audio clues comes at the end of “Strawberry Fields Forever”. As the song fades out for the second time, John allegedly says “I buried Paul.”‘ This audio clue can be heard more clearly when the record is played at 45 rpm as John’s voice is slowed down to a virtual crawl. Years later, John admitted that he was really saying “cranberry sauce,” which became evident on the “take 7 and edit piece” version of the song that appeared on Anthology II in 1996. Paul explained “That’s John’s humor. John would say something totally out of sync, like ‘cranberry sauce.’ If you don’t realize that John’s apt to say something like ‘cranberry sauce’ when he feels like it, then you start to hear a funny little word there, and you think aha!”

The “Paul is Dead” theorists prophetically point to the song, “I am the Walrus” on the album as definitive proof of McCartney’s death. The very fact that theorists looked for clues in “I Am the Walrus” was ironic, since John’s intent was to write a song with nonsensical imagery to poke fun at all those people looking for clues in every Beatle lyric. Still, John’s explanation didn’t stop them from looking for “Paul is Dead” clues in the song.

According to the “Paul is Dead” rumor: Paul left the recording studio in anger on a “stupid bloody Tuesday” after a quarrel with his bandmates. The refrain “I’m crying” is John expressing his grief over Paul’s death. The references to “pretty little policemen” and “waiting for the van to come” refer to the police present at the site of Paul’s fatal accident. The opening line of the song, “I am he as you are he as you are me and we are all together” suggests that all of the Beatles were aware of the death and ensuing cover-up. In the “Paul is dead” mythology, the walrus is an image of death. But no evidence for this statement has ever surfaced to explain why.

The album, movie and pictorial booklet are arguably the most ambitious effort ever attempted by the Fab Four. Completed at a time when the Beatles were still having fun, but questioning their viability at the same time. Although they saw themselves as a rock band, their fans were looking at them as modern day prophets. Undoubtedly, this view was responsible in large part for the devastation perceived by the “Paul is Dead” rumors that continued to swirl around the band. The band’s next effort, “The White Album”, would do nothing to help end the controversy.

The album, movie and pictorial booklet are arguably the most ambitious effort ever attempted by the Fab Four. Completed at a time when the Beatles were still having fun, but questioning their viability at the same time. Although they saw themselves as a rock band, their fans were looking at them as modern day prophets. Undoubtedly, this view was responsible in large part for the devastation perceived by the “Paul is Dead” rumors that continued to swirl around the band. The band’s next effort, “The White Album”, would do nothing to help end the controversy.

During that last tour, the airplane they were traveling in was shot at as they landed in Texas, and a prankster threw a firecracker at the stage during their Memphis show which everyone thought at first was a gunshot. The Beatles were burnt out and the band had had enough. The band’s attitude and message became darker and soon, concerts became dangerous as the Beatles’ started to receive death threats after some comments made by John Lennon at a press conference that year. John’s quote “the Beatles are bigger than Jesus” was taken out of context and according to John Lennon, “upset the very Christian KKK”. In the Philippines they unintentionally offended Imelda Marcos, a former beauty queen, by not meeting with her privately before their show. Filipino citizens took this as an excuse to rob, harass and threaten death to the Beatles. They stopped touring soon after the show at Candlestick Park in San Francisco on August 29, 1966. Less than six months later, the McCartney death rumor had reached a fever pitch worldwide and just like Paul himself, it refused to die.

During that last tour, the airplane they were traveling in was shot at as they landed in Texas, and a prankster threw a firecracker at the stage during their Memphis show which everyone thought at first was a gunshot. The Beatles were burnt out and the band had had enough. The band’s attitude and message became darker and soon, concerts became dangerous as the Beatles’ started to receive death threats after some comments made by John Lennon at a press conference that year. John’s quote “the Beatles are bigger than Jesus” was taken out of context and according to John Lennon, “upset the very Christian KKK”. In the Philippines they unintentionally offended Imelda Marcos, a former beauty queen, by not meeting with her privately before their show. Filipino citizens took this as an excuse to rob, harass and threaten death to the Beatles. They stopped touring soon after the show at Candlestick Park in San Francisco on August 29, 1966. Less than six months later, the McCartney death rumor had reached a fever pitch worldwide and just like Paul himself, it refused to die.

On the inside photo, Paul is wearing a patch on his band uniform with the letters “O.P.D.” that theorists interpreted as “Officially Pronounced Dead.” According to tradition, this British Police jargon “O.P.D.” phrase is the equivalent of American police forces use of “D.O.A.” (Dead On Arrival). (Much later, in a Life magazine article Paul stated, “It is all bloody stupid. I picked up the O.P.D. badge in Canada. It was a police badge. Perhaps it means Ontario Police Department or something.” Actually, the badge Paul was wearing reads “O.P.P.”, which stands for the Ontario Provincial Police. The angle of the photograph makes the final “P” look like a “D”.)

On the inside photo, Paul is wearing a patch on his band uniform with the letters “O.P.D.” that theorists interpreted as “Officially Pronounced Dead.” According to tradition, this British Police jargon “O.P.D.” phrase is the equivalent of American police forces use of “D.O.A.” (Dead On Arrival). (Much later, in a Life magazine article Paul stated, “It is all bloody stupid. I picked up the O.P.D. badge in Canada. It was a police badge. Perhaps it means Ontario Police Department or something.” Actually, the badge Paul was wearing reads “O.P.P.”, which stands for the Ontario Provincial Police. The angle of the photograph makes the final “P” look like a “D”.) Furthermore, the three black buttons on the waist above the tail of Paul’s coat are supposed to represent the mourning of the remaining Beatles. Although John, Paul and George were all about the same height (Ringo, much shorter), in the gatefold photo, Paul appears taller than the other Beatles, suggesting that he is ascending to the heavens. Another clue points out that next to Paul’s head are the words “WITHOUT YOU” from the song title “Within You Without You”.

Furthermore, the three black buttons on the waist above the tail of Paul’s coat are supposed to represent the mourning of the remaining Beatles. Although John, Paul and George were all about the same height (Ringo, much shorter), in the gatefold photo, Paul appears taller than the other Beatles, suggesting that he is ascending to the heavens. Another clue points out that next to Paul’s head are the words “WITHOUT YOU” from the song title “Within You Without You”.

Regardless, the album did nothing to quell the rumor that “Paul was Dead.” The Beatles, who were by this time totally fed up with dealing with the press, did little to dissuade the discussion of demise. Some pundits have speculated over the years that the entire affair was a ploy by the Beatles’ and their management designed to sell more albums. Which makes sense when you consider that the McCartney death rumor would continue to swirl around future album releases by the Fab Four in the coming years.

Regardless, the album did nothing to quell the rumor that “Paul was Dead.” The Beatles, who were by this time totally fed up with dealing with the press, did little to dissuade the discussion of demise. Some pundits have speculated over the years that the entire affair was a ploy by the Beatles’ and their management designed to sell more albums. Which makes sense when you consider that the McCartney death rumor would continue to swirl around future album releases by the Fab Four in the coming years.

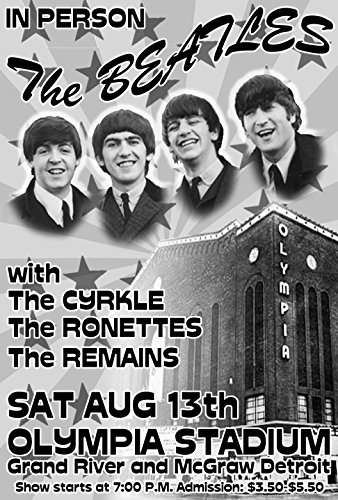

By the time the girls signed with Phil Spector in 1963, thanks mostly to Estelle, the Ronettes had their look precisely calibrated. In August of 1963 “Be My Baby” was released and by October, it had shot to No. 2 on the Billboard pop chart, making the Ronettes instant stars. The girls embarked on a tour of Britain in December of 1963 into early 1964. The Ronettes were the only girl group to tour with the Beatles. The Rolling Stiones were their opening act. When they toured, the Ronettes always traveled with at least one family member. In late 1964, the group released their only studio album, Presenting the Fabulous Ronettes Featuring Veronica, which entered the Billboard charts at number 96.

By the time the girls signed with Phil Spector in 1963, thanks mostly to Estelle, the Ronettes had their look precisely calibrated. In August of 1963 “Be My Baby” was released and by October, it had shot to No. 2 on the Billboard pop chart, making the Ronettes instant stars. The girls embarked on a tour of Britain in December of 1963 into early 1964. The Ronettes were the only girl group to tour with the Beatles. The Rolling Stiones were their opening act. When they toured, the Ronettes always traveled with at least one family member. In late 1964, the group released their only studio album, Presenting the Fabulous Ronettes Featuring Veronica, which entered the Billboard charts at number 96.

The duo were inseperable for the remainder of the English tour until The Beatles left for Paris. When The Beatles came to America, the Ronettes met them at their hotel in New York City. The Ronettes, in fact, were on hand February 8, 1964 to welcome the Beatles as they arrived in New York for their first U.S. visit and Ed Sullivan Show appearance. But the relationship fizzled out, Estelle saying, “We saw each other many times. I was with him at the party after their concert and on other evenings when we just sat around the hotel with the rest of the group. But somehow things weren’t the same. We couldn’t recreate the same relationship we had when I was in London…Over there he’s at his best, he’s relaxed, he’s George Harrison, Englishman and not George Harrison, Beatle.”

The duo were inseperable for the remainder of the English tour until The Beatles left for Paris. When The Beatles came to America, the Ronettes met them at their hotel in New York City. The Ronettes, in fact, were on hand February 8, 1964 to welcome the Beatles as they arrived in New York for their first U.S. visit and Ed Sullivan Show appearance. But the relationship fizzled out, Estelle saying, “We saw each other many times. I was with him at the party after their concert and on other evenings when we just sat around the hotel with the rest of the group. But somehow things weren’t the same. We couldn’t recreate the same relationship we had when I was in London…Over there he’s at his best, he’s relaxed, he’s George Harrison, Englishman and not George Harrison, Beatle.”

In Keith Richards autobiography “Life” he admitted that he was dating Ronnie when the Stones toured with the Ronettes in 1963. He recalled there that Mick Jagger got with Estelle because she was less “chaperoned” than Ronnie. The pairings were viewed as controversial for a couple of reasons. One was that management, particularly The Beatles’ Brian Epstein, wanted “the boys” to remain single for fans’ sake. And two, interracial pairings were taboo back in those days. Frowned upon in the U.K. and nearly suicidal in parts of the U.S.A.

In Keith Richards autobiography “Life” he admitted that he was dating Ronnie when the Stones toured with the Ronettes in 1963. He recalled there that Mick Jagger got with Estelle because she was less “chaperoned” than Ronnie. The pairings were viewed as controversial for a couple of reasons. One was that management, particularly The Beatles’ Brian Epstein, wanted “the boys” to remain single for fans’ sake. And two, interracial pairings were taboo back in those days. Frowned upon in the U.K. and nearly suicidal in parts of the U.S.A. In 1965, the Ronettes continued to record and tour while making a few appearances on television, including a CBS special and the NBC pop music show, Hullabaloo. However by this time, Phil Spector was busy with other artists. The 1965 song “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’,” produced and co-written by Spector for The Righteous Brothers, became a No. 1 hit. And by early 1966, he was preoccupied with Ike & Tina Turner. By now, The Ronettes were being moved to the back burner by Spector and some of their songs, such as “I Wish I Never Saw the Sunshine”, and two songs co-written by Harry Nilsson, “Paradise” and “Here I Sit,” were held back for decades. They had one last hurrah in August 1966 when the Ronettes (minus Ronnie) joined the Beatles on their 14-city U.S./Canada tour as one of the opening acts. As for the Rolling Stones, during one visit they made to New York in the 1960s, Ronnie’s mother ended up cooking for them at her Gotham City home.

In 1965, the Ronettes continued to record and tour while making a few appearances on television, including a CBS special and the NBC pop music show, Hullabaloo. However by this time, Phil Spector was busy with other artists. The 1965 song “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’,” produced and co-written by Spector for The Righteous Brothers, became a No. 1 hit. And by early 1966, he was preoccupied with Ike & Tina Turner. By now, The Ronettes were being moved to the back burner by Spector and some of their songs, such as “I Wish I Never Saw the Sunshine”, and two songs co-written by Harry Nilsson, “Paradise” and “Here I Sit,” were held back for decades. They had one last hurrah in August 1966 when the Ronettes (minus Ronnie) joined the Beatles on their 14-city U.S./Canada tour as one of the opening acts. As for the Rolling Stones, during one visit they made to New York in the 1960s, Ronnie’s mother ended up cooking for them at her Gotham City home.

Fellow 1960s singer Darlene Love, who once described The Ronettes as Rock’s tough girls, said the last time she saw Estelle, “She didn’t remember me.” By the early 2000s, Estelle Bennett was homeless. In 2007, The Ronettes were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Love recalled seeing Estelle at the induction ceremony. “They cleaned her up and made her look as well as possible…She looked the best she could for somebody who lived on the street. It broke my heart.” It was decided that she was too fragile to perform. A back-up singer with Ronnie Specter’s new group stood in for an encore performance of “Be My Baby”.

Fellow 1960s singer Darlene Love, who once described The Ronettes as Rock’s tough girls, said the last time she saw Estelle, “She didn’t remember me.” By the early 2000s, Estelle Bennett was homeless. In 2007, The Ronettes were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Love recalled seeing Estelle at the induction ceremony. “They cleaned her up and made her look as well as possible…She looked the best she could for somebody who lived on the street. It broke my heart.” It was decided that she was too fragile to perform. A back-up singer with Ronnie Specter’s new group stood in for an encore performance of “Be My Baby”.

Posthumously, all agreed that growing up, Estelle had been a force in creating the Ronettes’ style and act – and that she had a heart of gold. “Estelle had such an extraordinary life,” said her cousin, Nedra. “To have the fame, and all that she had at an early age, and for it all to come to an end abruptly. Not everybody can let that go and then go on with life.” “Not a bad bone in her body,” said her sister Ronnie in a press statement. “Just kindness.” At that 2007 Hall of Fame ceremony, Estelle spoke only two sentences during her acceptance speech, “I would just like to say, thank you very much for giving us this award. I’m Estelle of the Ronettes, thank you.” No, Estelle, we thank you.

Posthumously, all agreed that growing up, Estelle had been a force in creating the Ronettes’ style and act – and that she had a heart of gold. “Estelle had such an extraordinary life,” said her cousin, Nedra. “To have the fame, and all that she had at an early age, and for it all to come to an end abruptly. Not everybody can let that go and then go on with life.” “Not a bad bone in her body,” said her sister Ronnie in a press statement. “Just kindness.” At that 2007 Hall of Fame ceremony, Estelle spoke only two sentences during her acceptance speech, “I would just like to say, thank you very much for giving us this award. I’m Estelle of the Ronettes, thank you.” No, Estelle, we thank you.