PART II

Original publish date: November 12, 2020

The southern Indiana town of Warren, a stop on the route of the Indianapolis & Ft. Wayne Railroad in Huntington County, had one of the first local Horse Thief Detective Association chapters. The town’s story typifies why a HTDA chapter was needed. Warren had a race track that drew horses from across the tri-state area; horse thieves could easily ride trains and the interurban from larger neighboring cities, steal the horses, and hide them in Wells County caves – where the Huntington County sheriff couldn’t cross county lines to look for them. In 1800’s Indiana, a deputized vigilante force of constables was formed to track, arrest and detain these suspected horse thieves. Indiana was frontier back then. It might take days (or weeks) for a US Marshal to appear. So locals took matters into their own hands.

However, there was a frail line between being protectors of people and property and frontier vigilante justice. The latter, called whitecapping, led to the beating and very often lynching of people who whitecappers saw either as criminals or simply people whose actions were eroding the morality of a community. In many cases, by the turn of the 20th century, the NHTDA had devolved into a violent lawless movement among farmers defined by extralegal actions to enforce community standards, appropriate behavior, and traditional rights.

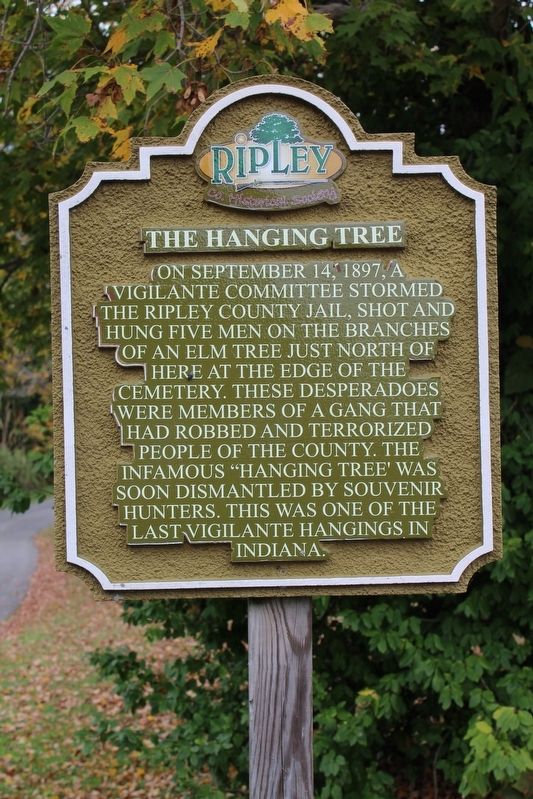

In September of 1897, newspapers reported on the “Versailles lynching,” or the “Ripley lynching” in which 400 men on horseback came to the Ripley County jail demanding that five men there, all facing charges for burglary and theft, be turned over to them. County residents were being victimized by thieves that were becoming bolder and more aggressive – sometimes conducting their crimes in broad daylight. One of the most egregious of these, which was reported to have led to the lynching, was the alleged torture of an elderly couple who had hot coals put to their feet by men demanding money. The deputy in charge of the jail refused to turn over the keys, but was quickly overpowered.

“The mob surged into the jail, and, unable to restrain their murderous feeling, fired on the prisoners. Then they placed ropes around their necks, dragged them (behind horses) to some trees a square away and swung them up,” according to an account in the Sept. 15, 1897, issue of The Madison Courier. The men killed were Lyle Levi, Bert Andrews, Clifford Gordon, William Jenkins and Hiney Shuler.

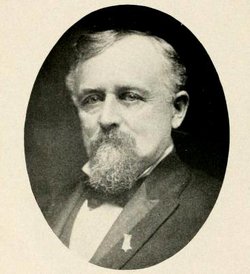

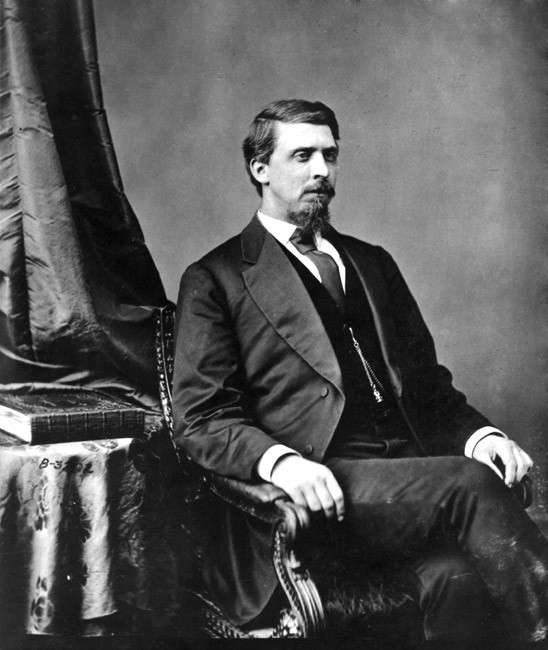

James A. Mount.

Indiana Governor James A. Mount had called immediately for those responsible for the lynching’s to be brought to justice, writing to Ripley County Sheriff Henry Bushing and ordering that he “proceed immediately with all the power you can command to bring to justice all the parties guilty of participation in the murder of the five men alleged to have been lynched. Such lawlessness is intolerable.” Despite his best efforts, the identity of those responsible for lynching these men was never discovered.

Anti-Horse Thief Association lapel badges.

Mount, who was ironically also the NHTDA’s president, reported that from 1890 to 1896 the association had investigated the theft of 75 horses and had recovered 65, leading to the conviction of 129 thieves. Mount condemned the lynching by saying, “The hideous crime of lynching is not to be measured by the worth or the character of the subject lynched, but by the dangerous precedent established,” he stated. “We would be unworthy of an organization created by the statutes if we dared to insult the law by becoming law breakers ourselves.” The vigilante spirit that once drove the organization ultimately turned ugly but remained strongest in Indianapolis.

The front page of the Feb. 25, 1925 Indianapolis Star reported that 13 Democratic State Senators bolted to Dayton, Ohio to thwart the forming of a quorum (subjecting themselves to a $ 1,000 fine per day) to pass an appropriation bill that included the gerrymandering of a Democratic Congressional District. The Star reported that “members of the Horse Thief Detective Association would come to Dayton to attempt to arrest the striking Senators.” It was clear that by 1925, the NHTDA had turned into little more than a well-organized mob of armed thugs with badges.

Anti-Horse Thief Association badge and watch fob.

By 1926 there were still as many as 300 active companies of the National Horse Thief Detective Association in Indiana and neighboring states. The western states version was known as the National Anti-Horse Thief Association and out east, the Horsethief Detection Society (founded in Medford, Massachusetts around 1807). And while by this time, horses were few, crime had not diminished much. By the Roaring Twenties, most of the NHTDA agencies had formed alliances with the Ku Klux Klan. It is this late association with the KKK that hastened the end of the organization and forever tarnished its history.

D.C. Stephenson, Grand Dragon of the Indiana KKK, wanted to take advantage of the broad legal powers afforded to Indiana’s horse thief detective associations. Stephenson utilized the Hoosier NHTDA chapters, still on the books but mostly forgotten, as his “hidden” enforcement arm of the KKK. He succeeded in having KKK members infiltrate the group. The post-World War I atmosphere fomented fears of political radicals, outsiders, foreigners, seditionists and minorities which played right into Stephenson’s klan plan. Stephenson’s klan latched onto fears of racism and, particularly in Irvington, anti-Catholic sentiment at the time.

Anti-Horse Thief Association ribbons.

Stephenson’s klan quickly gained momentum in the state (membership cresting at half a million members) but that all changed with his brutal assault on Madge Oberholtzer, an adult literacy advocate and state employee. Oberholtzer died of injuries suffered in the attack, but not before implicating Stephenson in a graphic 9-page deathbed statement that ultimately led to his conviction for second degree murder. Madge’s death brought down the klan and proved once and for all that, contrary to his boastful statements, he was no longer the law in Indiana.

Klan Leader D.C. Stephenson

Stephenson was denied a pardon by the Irvington resident he claimed to have gotten elected Governor: Ed Jackson. He began to leak the names of all those he had helped to elect with his influence and dirty klan money. D.C. Stephenson’s savage attack of Madge Oberholtzer in Irvington hastened the destruction of the KKK and took the NHTDA with it. (In 1928, the Indianapolis Times won a Pulitzer Prize for its coverage of the biggest scandal in the state’s history.)

In 1928, the group dropped the “Horse Thief” specification from its name in an attempt to rid itself of the Klan connection. The name change to “National Detective Association” didn’t take. By 1933, Indiana lawmakers had repealed all laws that gave the agency, regardless of name, any enforcement powers. These organizations remained on life support into the mid-1950s, but their reputations were ruined irreparably. By 1957, all such groups had faded into history. The desperate demise of the association has in many ways complicated its history. The Indiana organization, despite its onetime prominence and clear tie to the state’s history, has been largely stricken from the state’s history.

Like the Klan itself, association with the NHTDA in the Hoosier state seems to have become a taboo subject, deservedly so. So the task has fallen onto collectors, county historic societies, local libraries and archives to maintain records, roles and histories of local chapters of the NHTDA. However, the Anti Horse Thief Association fared somewhat better.

Likewise, the Anti Horse Thief Association was formed as a vigilance committee at Fort Scott, Kansas in 1859 with a noble cause: to provide protection against marauders thriving on border warfare precipitating the Civil War. It resembled other vigilance societies in organization and methods, but the AHTA did not share some of the shadier tactics of the Hoosier NHTDA. Kansas, Oklahoma and Missouri had the largest number of active AHTA chapters. A major difference between the AHTA and the NHTDA was that not only could a thief steal a horse and hurry across a state line, they could also escape into the Indian territories where local authorities could not easily follow. Stealing horses was easy and lucrative. Horses were seldom recovered, since it typically cost more to go after them than they were worth.

The AHTA was not a group of vigilantes, capturing horse thieves and hanging them from the nearest tree. The group believed in supporting and upholding the law, and the last thing they wanted to do was break the law. The AHTA worked hand in hand with law enforcement, gathering evidence and testifying in court to punish horse thieves and other criminals. It was a way for law-abiding citizens to restore order by working with law enforcement rather than becoming helpless victims.

Although it was a “secret” organization, nearly any man could join. To become a member of the AHTA, it was only necessary that you be a citizen in good standing, male and over eighteen years old. One of the reasons the AHTA was so successful was because the members didn’t have to worry about getting extradition orders and crossing state lines while bringing back a thief. The AHTA had a clever way around this. If a thief was chased into another state, part of that state’s AHTA group would remain close to the state line. When captured, they would take him to the line and tell him to, “get out of our state and don’t come back.” As soon as the thief crossed the state line he would be arrested by AHTA members on the other side waiting for him.

AHTA membership peaked at 50,000 in 1916. As with the NHTDA, World War I changed rural life, members left for the war, many never to return, and mechanization replaced horsepower. As automation took over, and horses were used less, stealing them became a misdemeanor offense. By the Great Depression and Dust Bowl, AHTA membership shrank drastically, only a few individual chapters survived as social clubs.

Although the Horse Thief Associations are all gone now, horse thieving still exists. There are no solid statistics available, but it is estimated that between 40,000 to 55,000 horses are stolen each year. It is relatively easy to pull up to a pasture and coax a horse into a trailer and haul it to an auction and make a quick buck. Sadly, most of these stolen horses taken to auction end up at a slaughterhouse. There is a modern-day version of the AHTA. It is called Stolen Horse International (SHI). Thanks mostly to the Internet, SHI boasts a 51% recovery rate of stolen horses that are reported within the first day of the theft.

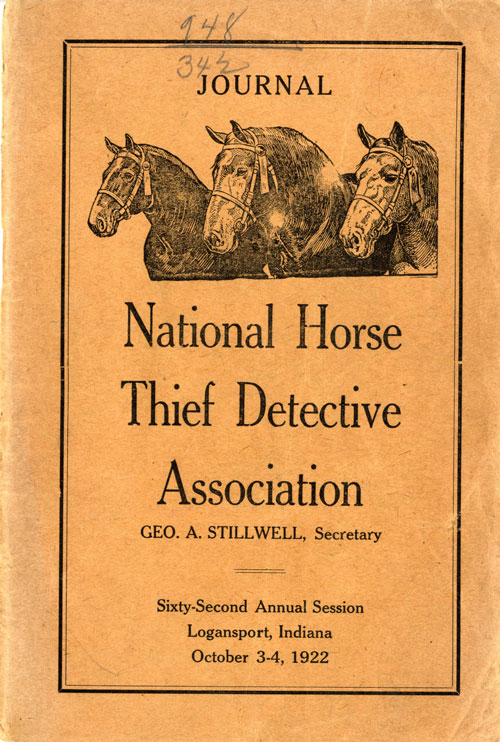

And what what remains of Indiana’s NHTDA? Today, badges once worn by HTDA, NHTDA and AHTA members are highly prized by collectors. Badges vary in style, size and design according to chapter and year. Collectors also seek out buggy markers (designed to be nailed to a buggy to signify a buggy owner’s membership) and books, stickpins and ribbons are also highly sought after. Relics from a lost era when horses were a part of the family and the only pollution being produced could fertilize your garden.

Buffalo Bill Cody was the real deal-he had fought Indians, hunted buffalo, and scouted the Northern Plains for General Phil Sheridan and Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer along America’s vast Western frontier. He was a fur-trapper, gold-miner, bullwhacker, wagon master, stagecoach driver, dude rancher, camping guide, big game hunter, hotel manager, Pony Express rider, Freemason and inventor of the traveling Wild West show. Oh, yeah, and he was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1872 for, unsurprisingly, “Gallantry” during the Indian Wars. His medal, along with medals of 910 other recipients, was revoked in February of 1917 when Congress retroactively tightened the rules for the honor. Luckily, the action came one month after Cody died in 1917. It was reinstated in 1989.

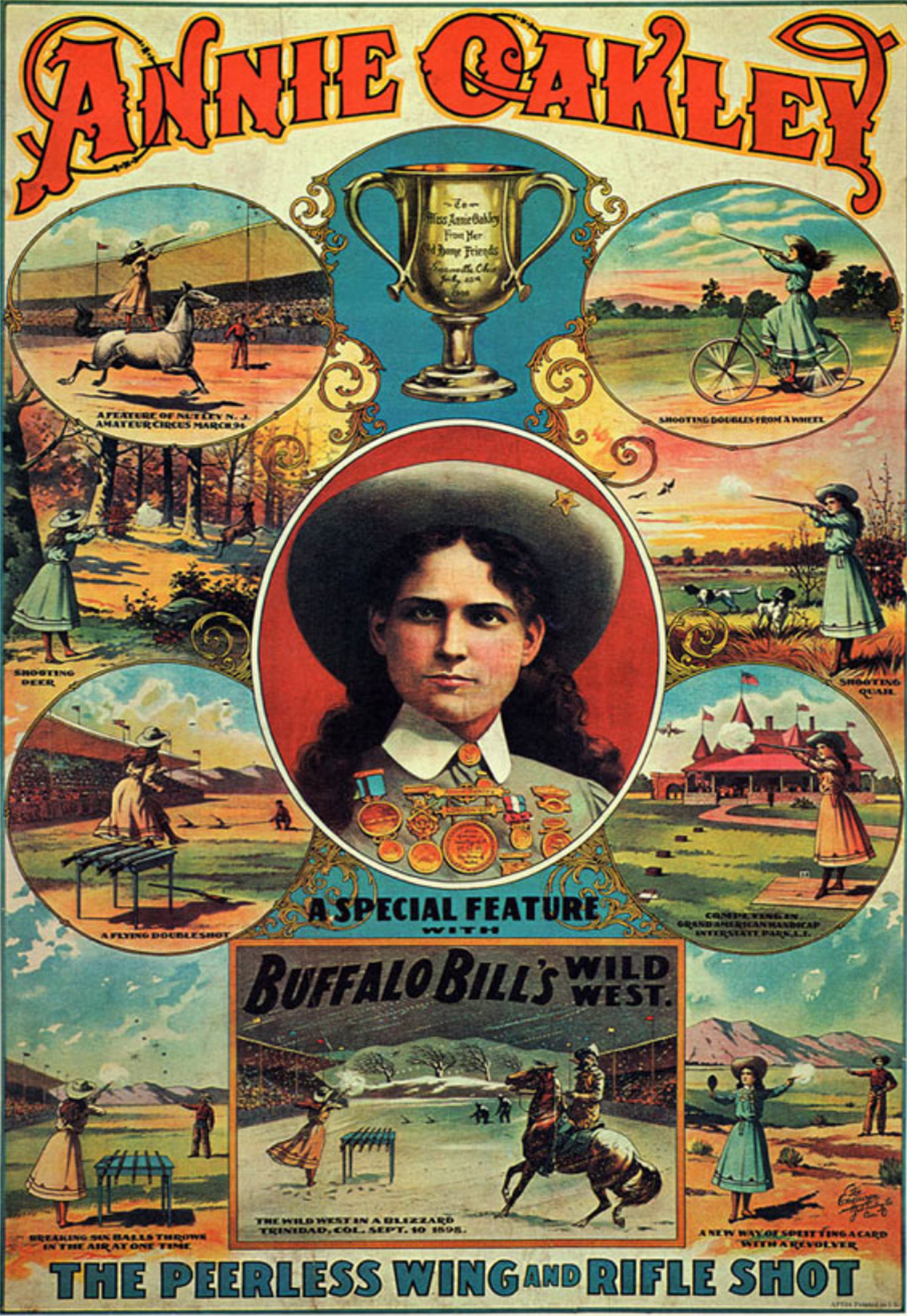

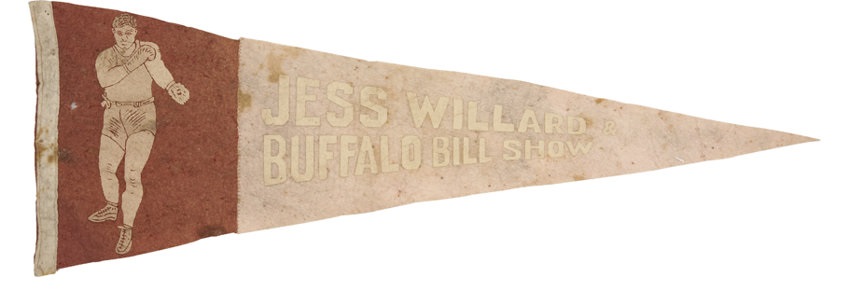

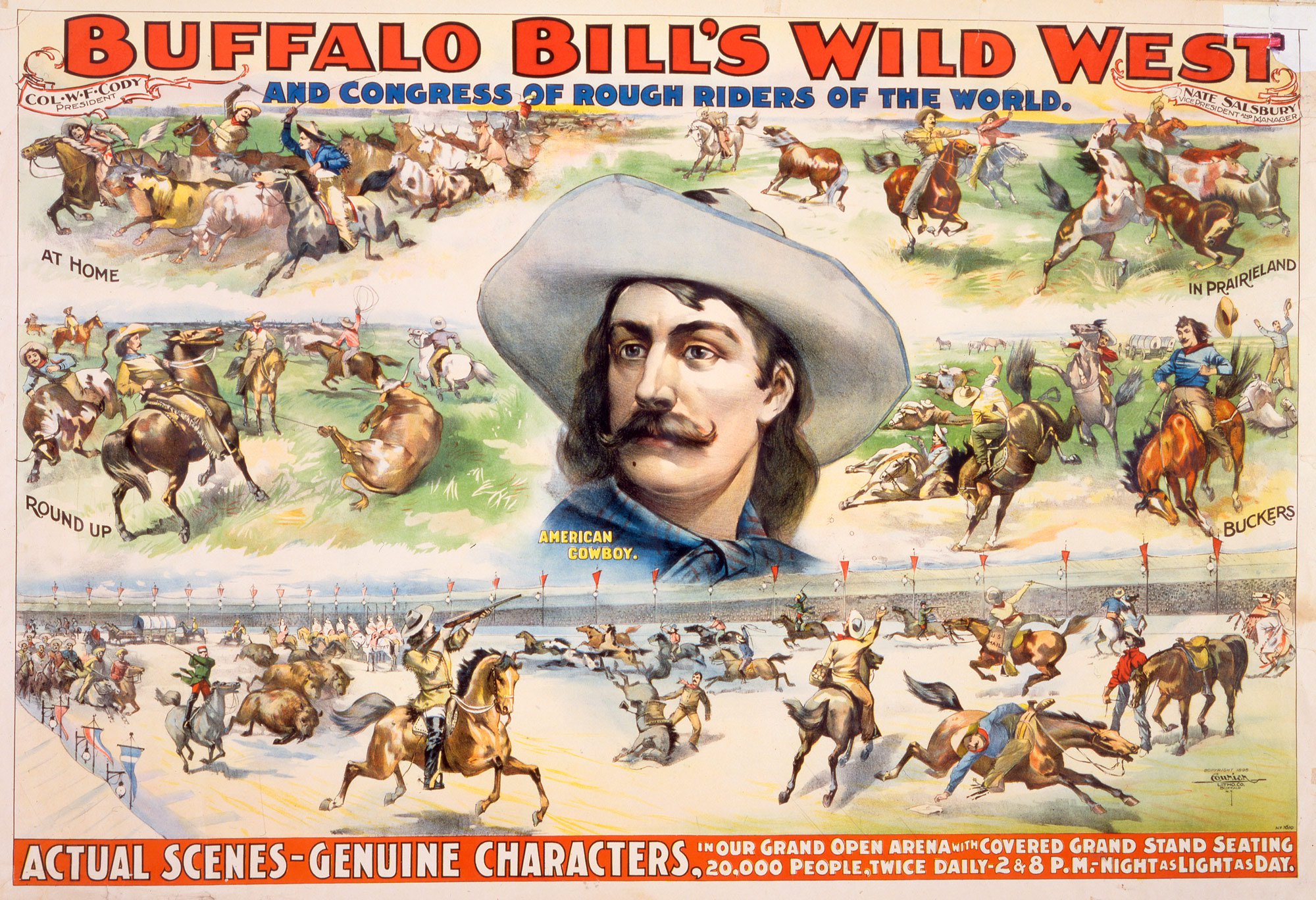

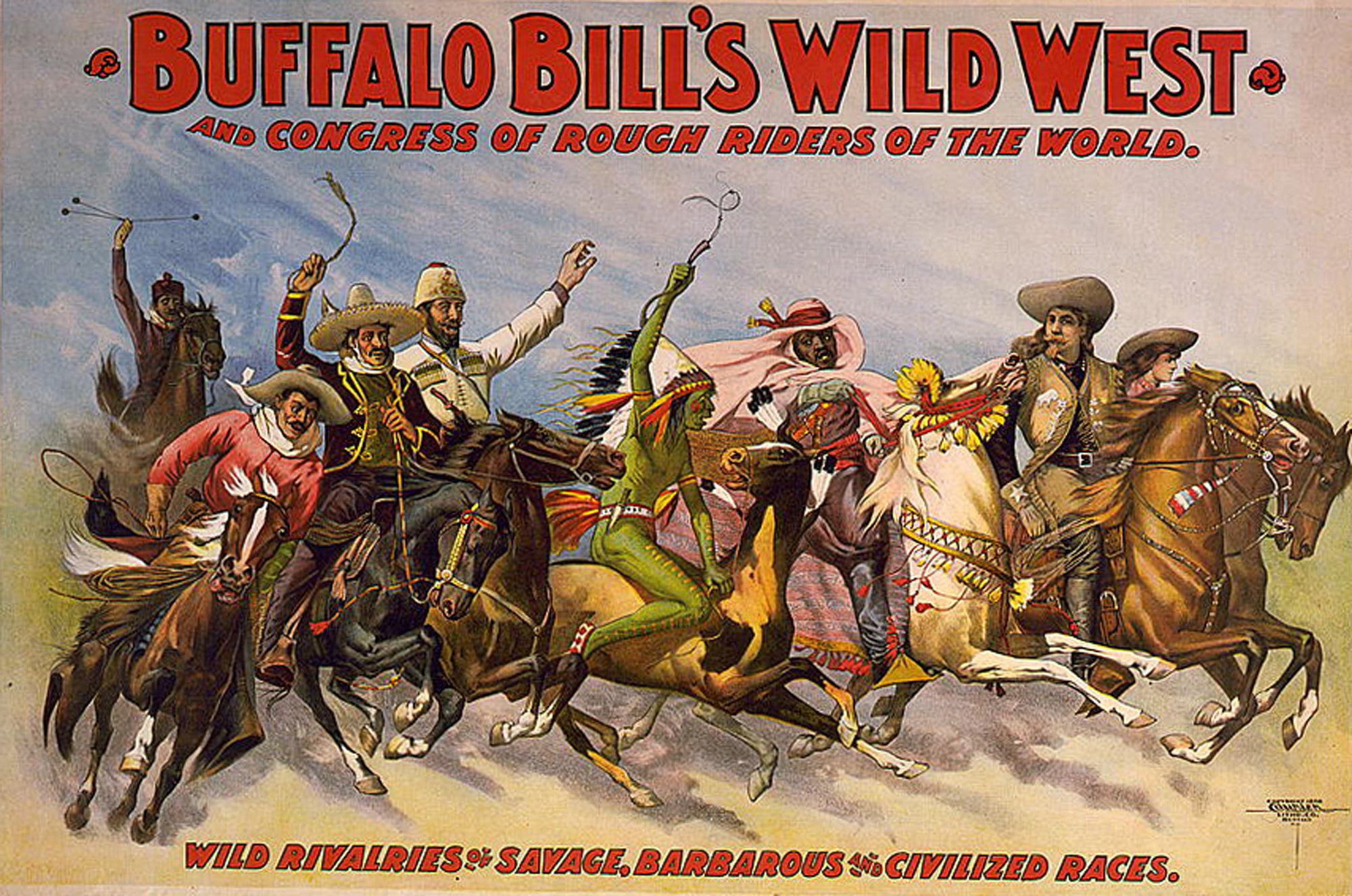

Buffalo Bill Cody was the real deal-he had fought Indians, hunted buffalo, and scouted the Northern Plains for General Phil Sheridan and Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer along America’s vast Western frontier. He was a fur-trapper, gold-miner, bullwhacker, wagon master, stagecoach driver, dude rancher, camping guide, big game hunter, hotel manager, Pony Express rider, Freemason and inventor of the traveling Wild West show. Oh, yeah, and he was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1872 for, unsurprisingly, “Gallantry” during the Indian Wars. His medal, along with medals of 910 other recipients, was revoked in February of 1917 when Congress retroactively tightened the rules for the honor. Luckily, the action came one month after Cody died in 1917. It was reinstated in 1989. But Cody’s biggest achievement came as the wild west frontier he had helped create was vanishing. Buffalo Bill’s “Wild West” shows featured western icons like Wild Bill Hickok, Annie Oakley, Frank Butler, Bill Pickett, Mexican Joe, Adam Bogardus, Buck Taylor, Geronimo, Red Cloud, Chief Joseph, Texas Jack, Pawnee Bill, Tillie Baldwin, Bronco Bill, Coyote Bill, May Lillie, and a “Congress” of cowboys, soldiers, Native American Indians and Mexican vaqueros. Movie stars Will Rogers and Tom Mix and World Heavyweight Champion Jess Willard kicked off their careers as common cow punchers for Buffalo Bill. Cody performed for Kings, Queens, Presidents, Generals, Dignitaries and just plain folk in small towns, at World’s Fairs, stadiums and arenas all over the world.

But Cody’s biggest achievement came as the wild west frontier he had helped create was vanishing. Buffalo Bill’s “Wild West” shows featured western icons like Wild Bill Hickok, Annie Oakley, Frank Butler, Bill Pickett, Mexican Joe, Adam Bogardus, Buck Taylor, Geronimo, Red Cloud, Chief Joseph, Texas Jack, Pawnee Bill, Tillie Baldwin, Bronco Bill, Coyote Bill, May Lillie, and a “Congress” of cowboys, soldiers, Native American Indians and Mexican vaqueros. Movie stars Will Rogers and Tom Mix and World Heavyweight Champion Jess Willard kicked off their careers as common cow punchers for Buffalo Bill. Cody performed for Kings, Queens, Presidents, Generals, Dignitaries and just plain folk in small towns, at World’s Fairs, stadiums and arenas all over the world. During the late 19th century, the troupe included as many as 1,200 performers.The shows consisted of historical scenes punctuated by feats of sharpshooting, military drills, staged races, rodeo events, and sideshows. Real live Native American Indians were portrayed as the “Bad Guys”, most often shown attacking wagon trains with Buffalo Bill or one of his colleagues riding in and saving the day. Other staged scenes included Pony Express riders, stagecoach robberies, buffalo-hunting and a melodramatic re-enactment of Custer’s Last Stand in which Cody himself portrayed General Custer.

During the late 19th century, the troupe included as many as 1,200 performers.The shows consisted of historical scenes punctuated by feats of sharpshooting, military drills, staged races, rodeo events, and sideshows. Real live Native American Indians were portrayed as the “Bad Guys”, most often shown attacking wagon trains with Buffalo Bill or one of his colleagues riding in and saving the day. Other staged scenes included Pony Express riders, stagecoach robberies, buffalo-hunting and a melodramatic re-enactment of Custer’s Last Stand in which Cody himself portrayed General Custer. By the turn of the 20th century, William F. Cody was probably the most famous American in the world. Cody symbolized the West for Americans and Europeans, his shows seen as the entertainment triumphs of the ages. In Indiana, entire towns turned out to see the people and scenes they had read about in the dime novels and newspaper stories they grew up on and continued to read daily. Buffalo Bill’s performances were usually preceded by a downtown parade of stagecoaches, soldiers, acrobats, wild animals, chuckwagons, calliopes, cowboys, Indians, outlaws and trick shooters firing off birdshot at targets thrown haphazardly in the air. In 1898, admission to the show was half-a-buck for adults, two bits for children under 9. The Buffalo Bill show traveled by their own special train, usually arriving early in the morning and giving two shows before packing up to travel all night to the next town.

By the turn of the 20th century, William F. Cody was probably the most famous American in the world. Cody symbolized the West for Americans and Europeans, his shows seen as the entertainment triumphs of the ages. In Indiana, entire towns turned out to see the people and scenes they had read about in the dime novels and newspaper stories they grew up on and continued to read daily. Buffalo Bill’s performances were usually preceded by a downtown parade of stagecoaches, soldiers, acrobats, wild animals, chuckwagons, calliopes, cowboys, Indians, outlaws and trick shooters firing off birdshot at targets thrown haphazardly in the air. In 1898, admission to the show was half-a-buck for adults, two bits for children under 9. The Buffalo Bill show traveled by their own special train, usually arriving early in the morning and giving two shows before packing up to travel all night to the next town. According to the official “Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave in Golden, Colorado” website, from 1873 to 1916 William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody appeared in Indiana 155 times, touring 38 different Hoosier cities. Some of those cities are obvious, some obscure. Anderson (3 times), Auburn, Bedford, Bluffton, Columbus, Crawfordsville (2 times), Elkhart (3 times), Evansville (12 times), Fort Wayne (12 times), Frankfort, Gary (2 times), Goshen (2 times), Huntington, Kendallville, Kokomo (4 times), La Porte, Lafayette (14 times), Lawrenceburg, Logansport (8 times), Madison, Marion (3 times), Michigan City, Muncie (7 times), New Albany (3 times), North Vernon (4 times), Peru, Plymouth, Portland, Richmond (8 times), Shelbyville, South Bend (8 times), Tell City, Terre Haute (17 times), Valparaiso, Vincennes (4 times), Warsaw (2 times), Washington and of course Indianapolis (19 times). Strangely, although Buffalo Bill appeared in the Circle City more than any other during his career, his tour did not stop here for his final tour in 1916. preferring instead to swing thru the far northern section of our state on the way to Chicago.

According to the official “Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave in Golden, Colorado” website, from 1873 to 1916 William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody appeared in Indiana 155 times, touring 38 different Hoosier cities. Some of those cities are obvious, some obscure. Anderson (3 times), Auburn, Bedford, Bluffton, Columbus, Crawfordsville (2 times), Elkhart (3 times), Evansville (12 times), Fort Wayne (12 times), Frankfort, Gary (2 times), Goshen (2 times), Huntington, Kendallville, Kokomo (4 times), La Porte, Lafayette (14 times), Lawrenceburg, Logansport (8 times), Madison, Marion (3 times), Michigan City, Muncie (7 times), New Albany (3 times), North Vernon (4 times), Peru, Plymouth, Portland, Richmond (8 times), Shelbyville, South Bend (8 times), Tell City, Terre Haute (17 times), Valparaiso, Vincennes (4 times), Warsaw (2 times), Washington and of course Indianapolis (19 times). Strangely, although Buffalo Bill appeared in the Circle City more than any other during his career, his tour did not stop here for his final tour in 1916. preferring instead to swing thru the far northern section of our state on the way to Chicago. Buffalo Bill traveled with five different shows during his lifetime: 1872 – 1886: Buffalo Bill’s Combination acting troop / 1884 – 1908: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West / 1909 – 1913: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Pawnee Bill’s Far East / 1914 – 1915: Sells-Floto Circus and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West / 1916: Buffalo Bill and the 101 Ranch Combined. By the end, Buffalo Bill had to be strapped onto his saddle to keep from falling off (after all, he was over 70-years old at the time). Despite the perceived exploitation of his Wild West Shows, Cody respected Native Americans, was among the earliest supporters of women’s rights and was a pioneer in the conservation movement and an early advocate for civil rights. He described Native Americans as “the former foe, present friend, the American” and once said that “every Indian outbreak that I have ever known has resulted from broken promises and broken treaties by the government.” He also said, “What we want to do is give women even more liberty than they have. Let them do any kind of work they see fit, and if they do it as well as men, give them the same pay.”

Buffalo Bill traveled with five different shows during his lifetime: 1872 – 1886: Buffalo Bill’s Combination acting troop / 1884 – 1908: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West / 1909 – 1913: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Pawnee Bill’s Far East / 1914 – 1915: Sells-Floto Circus and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West / 1916: Buffalo Bill and the 101 Ranch Combined. By the end, Buffalo Bill had to be strapped onto his saddle to keep from falling off (after all, he was over 70-years old at the time). Despite the perceived exploitation of his Wild West Shows, Cody respected Native Americans, was among the earliest supporters of women’s rights and was a pioneer in the conservation movement and an early advocate for civil rights. He described Native Americans as “the former foe, present friend, the American” and once said that “every Indian outbreak that I have ever known has resulted from broken promises and broken treaties by the government.” He also said, “What we want to do is give women even more liberty than they have. Let them do any kind of work they see fit, and if they do it as well as men, give them the same pay.” Although many reports make it seem that Buffalo Bill died a pauper, at the time of his death on January 10, 1917, Cody’s fortune had “dwindled” to less than $100,000 (approximately $2 million today). So you see, there is more to Buffalo Bill Cody than meets the eye. Although often portrayed in pantomime as a grossly exaggerated caricature of a buckskin clad circus act, he really was the real deal.

Although many reports make it seem that Buffalo Bill died a pauper, at the time of his death on January 10, 1917, Cody’s fortune had “dwindled” to less than $100,000 (approximately $2 million today). So you see, there is more to Buffalo Bill Cody than meets the eye. Although often portrayed in pantomime as a grossly exaggerated caricature of a buckskin clad circus act, he really was the real deal.

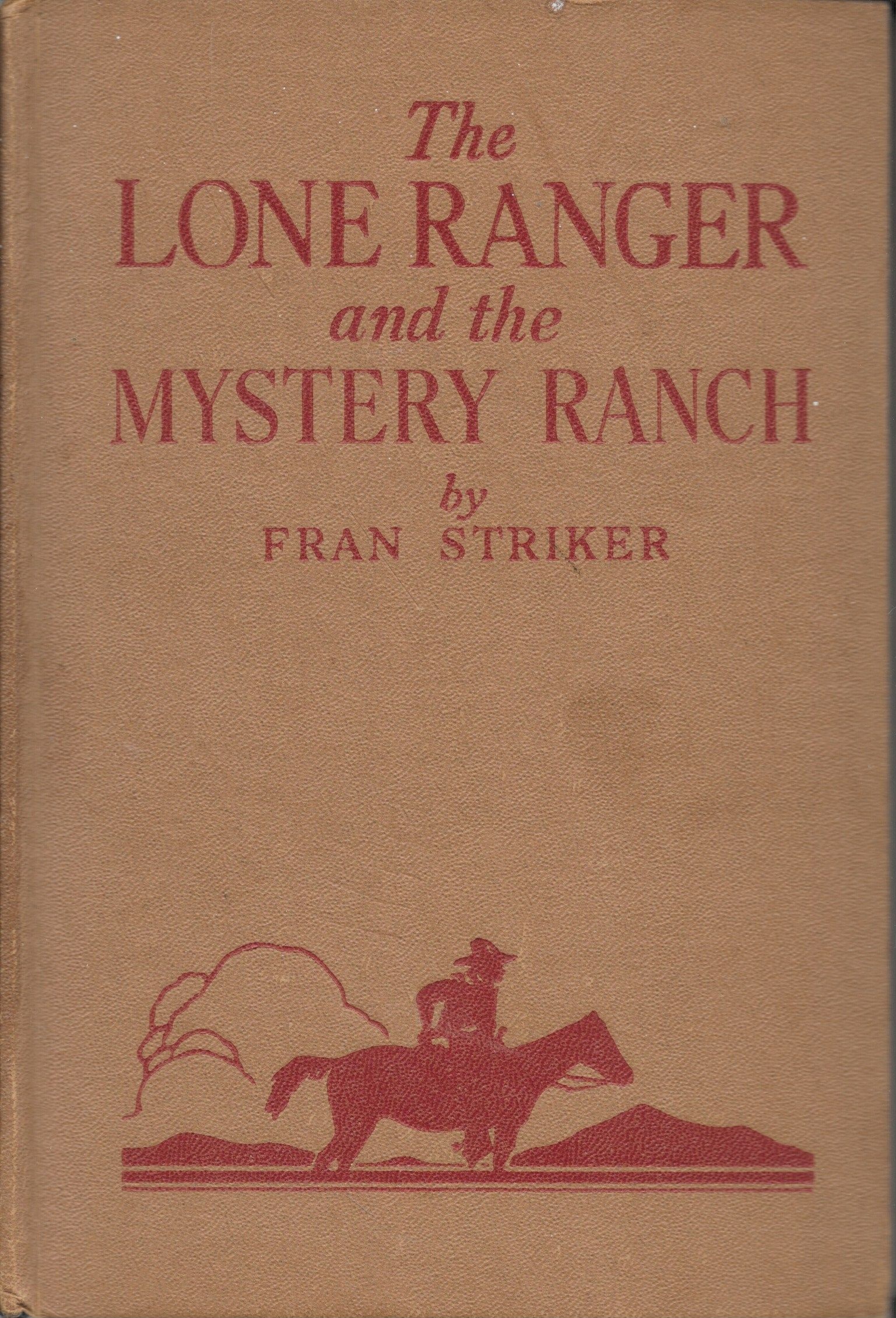

He also shared stories of the Lone Ranger from movie, television and real life. “The closest I ever got to the part was in 1945 when I played Little Beaver with Wild Bill Elliott in the Red Ryder serial “Lone Texas Ranger.” Blake said, “I always modeled Little Beaver after Tonto you know.” Keep in mind, this was WAY before Google in an age when these tidbits were only known to the participants. It was Robert Blake who first told me the true story of the Lone Ranger.

He also shared stories of the Lone Ranger from movie, television and real life. “The closest I ever got to the part was in 1945 when I played Little Beaver with Wild Bill Elliott in the Red Ryder serial “Lone Texas Ranger.” Blake said, “I always modeled Little Beaver after Tonto you know.” Keep in mind, this was WAY before Google in an age when these tidbits were only known to the participants. It was Robert Blake who first told me the true story of the Lone Ranger.

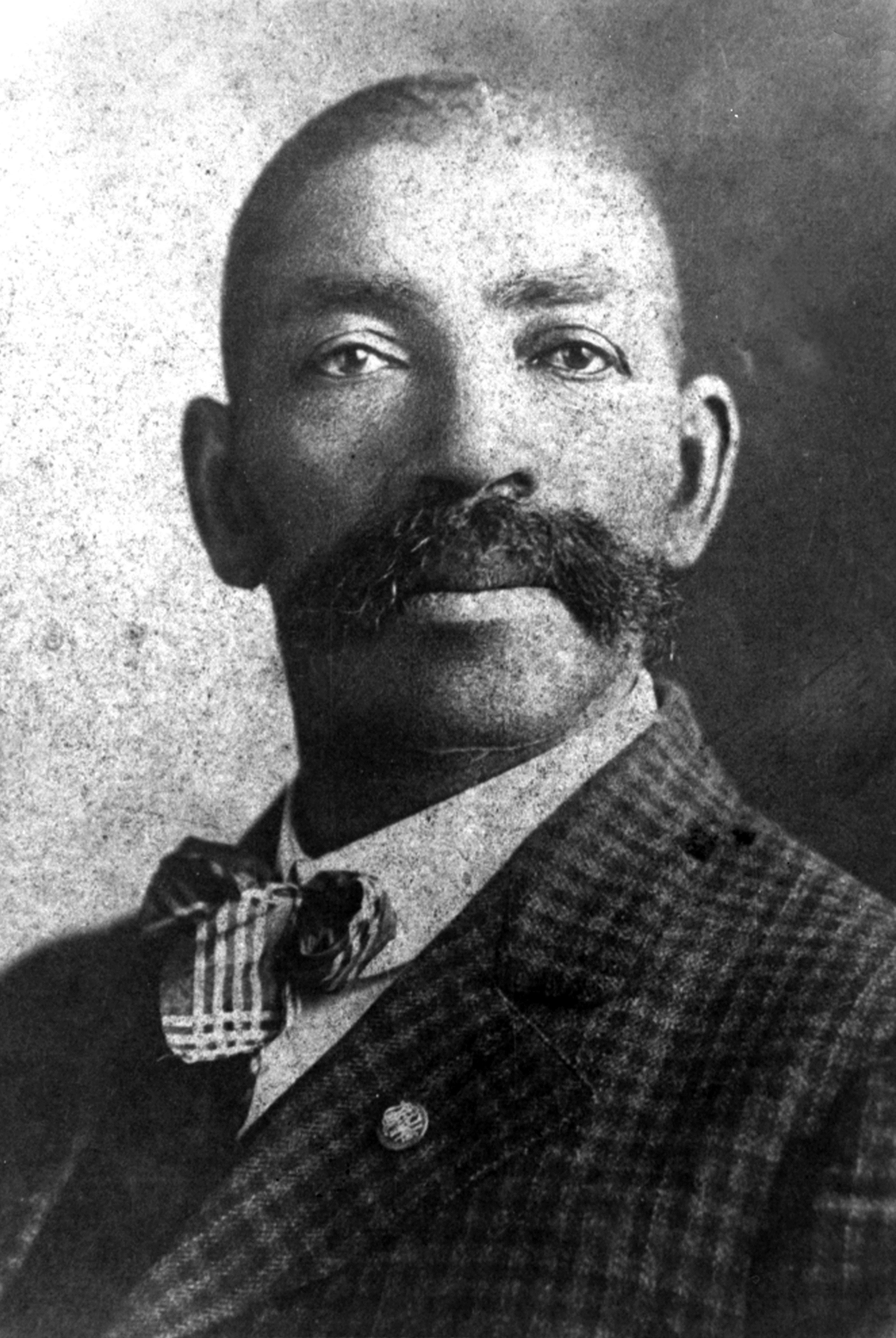

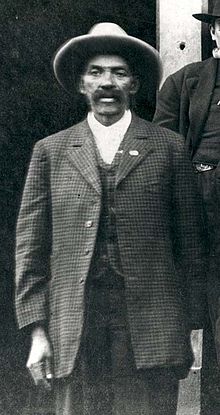

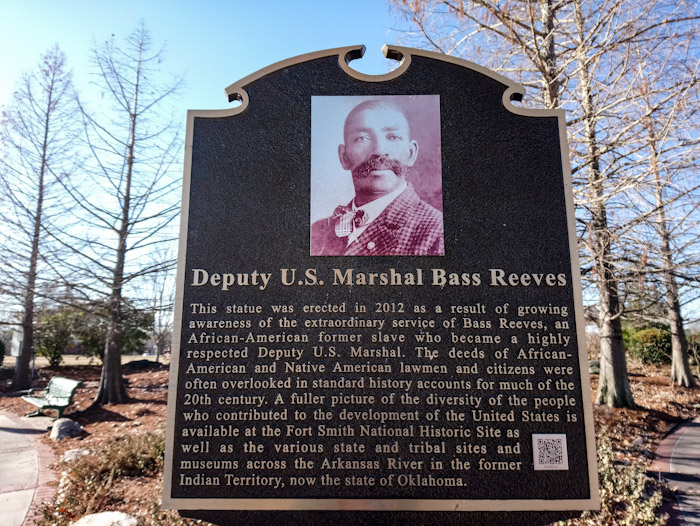

Reeves, born a slave in July of 1838, accompanied his “master” Arkansas state legislator William Steele Reeves’ son, Colonel George R. Reeves, as a personal servant when he went off to fight with the Confederate Army during the Civil War. Col. Reeves, of the CSA’s 11th Texas Cavalry Regiment, was a sheriff, tax collector, legislator, and a one-time Speaker of the Texas House of Representatives. During the Civil War, the Texas 11th Cavalry was involved in some 150 battles and skirmishes. Records are sketchy, but one report states that although 500 men served with the unit, less than 50 returned home at the end of the war.

Reeves, born a slave in July of 1838, accompanied his “master” Arkansas state legislator William Steele Reeves’ son, Colonel George R. Reeves, as a personal servant when he went off to fight with the Confederate Army during the Civil War. Col. Reeves, of the CSA’s 11th Texas Cavalry Regiment, was a sheriff, tax collector, legislator, and a one-time Speaker of the Texas House of Representatives. During the Civil War, the Texas 11th Cavalry was involved in some 150 battles and skirmishes. Records are sketchy, but one report states that although 500 men served with the unit, less than 50 returned home at the end of the war.

Ironically, Bass Reeves was himself once charged with murdering a posse cook. At his trial before Judge Parker, Reeves was represented by former United States Attorney W. H. H. Clayton, who had been his colleague and friend. Reeves was acquitted. On another instance, Reeves arrested his own son for murder. One of his sons, Bennie Reeves, was charged with the murder of his wife. Although understandably disturbed and shaken by the incident, Deputy Marshal Reeves nonetheless demanded the responsibility of bringing Bennie to justice. Bennie was eventually tracked and captured, tried, and convicted. He served his time in Fort Leavenworth in Kansas before being released, and reportedly lived the rest of his life as a responsible and model citizen.

Ironically, Bass Reeves was himself once charged with murdering a posse cook. At his trial before Judge Parker, Reeves was represented by former United States Attorney W. H. H. Clayton, who had been his colleague and friend. Reeves was acquitted. On another instance, Reeves arrested his own son for murder. One of his sons, Bennie Reeves, was charged with the murder of his wife. Although understandably disturbed and shaken by the incident, Deputy Marshal Reeves nonetheless demanded the responsibility of bringing Bennie to justice. Bennie was eventually tracked and captured, tried, and convicted. He served his time in Fort Leavenworth in Kansas before being released, and reportedly lived the rest of his life as a responsible and model citizen.