Original publish date: November 28, 2019

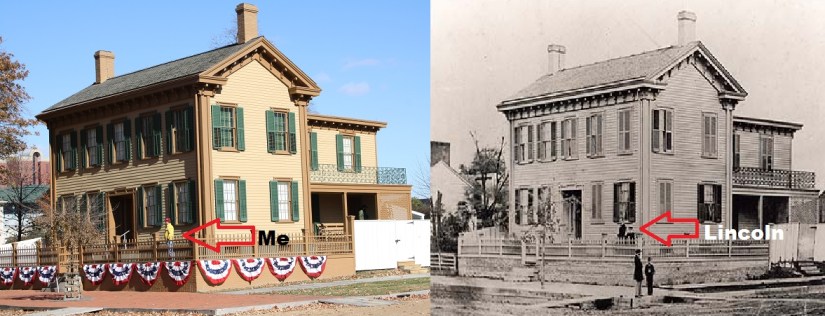

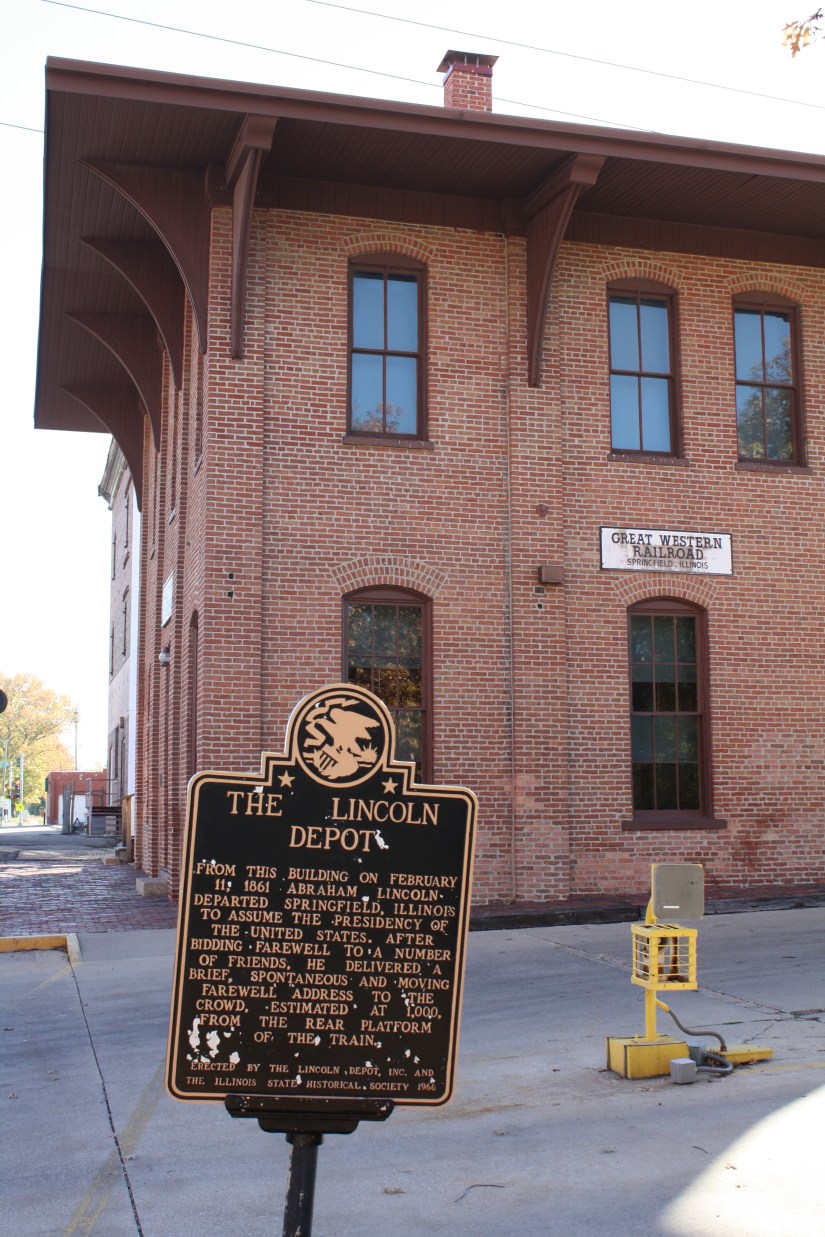

As Thanksgiving approaches, I must admit, I’m still stuck in Halloween mode. After all, despite the recent measurable snowfall, autumn is still in session and my thoughts always wander towards ghost stories at Christmas (remember friends, Scrooge is a ghost story). In a couple weeks, families will gather together to give thanks for all of the blessings bestowed upon them during the past year. While images of Pilgrims in high hats, square-toed shoes and plain brown clothing dance through our heads, it should be remembered that it was Abraham Lincoln who gave us the modern version of Thanksgiving. On October 3, 1863, three months to the day after the pivotal Union Army victory at Gettysburg, a grateful President Abraham Lincoln announced that the nation will celebrate an official Thanksgiving holiday that November 26. Well, the nation north of the Mason-Dixon line anyway.

Although Lincoln was the first to officially recognize the U.S. holiday of Thanksgiving, Halloween was just beginning to take root during the Civil War. Some historians credit the Irish for “inventing” Halloween in the United States. Or more specifically, the Irish “little people” with a tendency toward vandalism, and their tradition of “Mischief Night” that spread quickly through rural areas. According to American Heritage magazine (October 2001 / Vol. 52, Issue 7), “On October 31, young men roamed the countryside looking for fun, and on November 1, farmers would arise to find wagons on barn roofs, front gates hanging from trees, and cows in neighbors’ pastures. Any prank having to do with an outhouse was especially hilarious, and some students of Halloween maintain that the spirit went out of the holiday when plumbing moved indoors.”

Although Lincoln was the first to officially recognize the U.S. holiday of Thanksgiving, Halloween was just beginning to take root during the Civil War. Some historians credit the Irish for “inventing” Halloween in the United States. Or more specifically, the Irish “little people” with a tendency toward vandalism, and their tradition of “Mischief Night” that spread quickly through rural areas. According to American Heritage magazine (October 2001 / Vol. 52, Issue 7), “On October 31, young men roamed the countryside looking for fun, and on November 1, farmers would arise to find wagons on barn roofs, front gates hanging from trees, and cows in neighbors’ pastures. Any prank having to do with an outhouse was especially hilarious, and some students of Halloween maintain that the spirit went out of the holiday when plumbing moved indoors.”

So it is that the origins of our two most celebrated autumnal holidays trace their American roots directly to our sixteenth President. And no President in American history is more closely associated with ghosts than Abraham Lincoln. However, where did all of these Lincoln ghost stories originate? After all, they had to start somewhere because one thing is for certain, they didn’t come from Abraham Lincoln. Many historians believe that most of those stories (at least the Lincoln ghost stories in the White House) came from a middle-aged freedman born in Anne Arundel County Maryland who worked as a White House “footman” serving nine Presidents from U.S. Grant to Teddy Roosevelt. His duties as footman included service as butler, cook, doorman, light cleaning and maintenance.

So it is that the origins of our two most celebrated autumnal holidays trace their American roots directly to our sixteenth President. And no President in American history is more closely associated with ghosts than Abraham Lincoln. However, where did all of these Lincoln ghost stories originate? After all, they had to start somewhere because one thing is for certain, they didn’t come from Abraham Lincoln. Many historians believe that most of those stories (at least the Lincoln ghost stories in the White House) came from a middle-aged freedman born in Anne Arundel County Maryland who worked as a White House “footman” serving nine Presidents from U.S. Grant to Teddy Roosevelt. His duties as footman included service as butler, cook, doorman, light cleaning and maintenance.

Jeremiah “Jerry” Smith was a free born African American man born below the Mason-Dixon line in 1835. No small feat when you consider that, in 1850, 71 percent of Maryland’s black population was enslaved. Smith was an imposing figure, standing over 6 feet tall in an age when the average man stood 5 foot 8 inches in height. Although little is known about Smith’s personal history, by all accounts, Jerry had the manners of a country gentleman. During the Civil War, he served as a teamster for the Union Army, guiding vital supply trains made up of wagons, horses, and mules. It is believed that somewhere during the conflict, he made the acquaintance of General Ulysses S. Grant. Grant, perhaps our greatest presidential horseman, no doubt appreciated Smith’s equine expertise.

At war’s end, Smith was working as a waiter in a Baltimore restaurant when his old acquaintance U.S. Grant came calling. After Grant was elected President, Smith went to work in the Grant White House and would serve from the age of Reconstruction through the Gilded Age and into the Progressive Era.

One of the few detailed descriptions of Smith comes from Col. William H. Crook, a White House Secret Service agent and onetime personal bodyguard of Abraham Lincoln. Crook, in a book detailing his nearly 50 years of service in the White House, said that Smith was “one of the best known employees in the WH, who began his career as Grant’s footman, and remained in the WH ever since, and still was one of the most magnificent specimens of manhood the colored race has produced. In addition to his splendid appearance, he had the manner of a courtier, and a strong personality that could not be overlooked by anyone, high or low.”

Crook claimed that Smith was “incredibly superstitious and believed in ghosts the same way a five-year-old believes in Santa Claus – and no one could tell him any different. Since the WH has always been home to benevolent ghosts, Jerry Smith had a varied assortment of stories about the origin of the creaks and groans he heard, and happy to share them with all who would listen…he was always seeing or hearing the ghosts of former deceased Presidents hovering around in out-of-the-way corners, especially in deep shadows at sundown, or later.” Smith believed these ghosts had every right to haunt their former home and never questioned that right, “being perfectly willing to let them do whatever they wished so long as they let him alone.”

Jeremiah would often spin yarns for visiting reporters. Most of these tall tales were pure Americana always designed to bolster the reputation of his employer and their families, but some of Jerry’s best remembered tales were spooky ghost stories. Smith claimed that he saw the ghosts of Presidents Lincoln, Grant, and McKinley, and that they tried to speak to him but only produced a buzzing sound.

Jeremiah would often spin yarns for visiting reporters. Most of these tall tales were pure Americana always designed to bolster the reputation of his employer and their families, but some of Jerry’s best remembered tales were spooky ghost stories. Smith claimed that he saw the ghosts of Presidents Lincoln, Grant, and McKinley, and that they tried to speak to him but only produced a buzzing sound.

However, when it came to White House spirits, Abraham Lincoln’s ghost grabbed the lion’s share of the headlines. Smith most often held court at the North Entrance (where the press corps came and went) with his signature feather duster in his hand and a fantastical story at the ready (if needed). Soon, newspapermen began calling him the “Knight of the Feather Duster” and routinely consulted Smith for comment on days when Presidential news was thin.

One Chicago reporter said this about Smith: “He is a firm believer in ghosts and their appurtenances, and he has a fund of stories about these uncanny things that afford immense entertainment for those around him. But there is one idea that has grown into Jerry’s brain and is now part of it, resisting the effects or ridicule, laughter, argument, or explanation. He firmly believes that the White House is haunted by the spirits of all the departed Presidents, and, furthermore, that his Satanic majesty, the devil, has his abode in the attic. He cannot be persuaded out of the notion, and at intervals he strengthens his position by telling about some new strange noise he has heard or some additional evidence he has secured.”

One Chicago reporter said this about Smith: “He is a firm believer in ghosts and their appurtenances, and he has a fund of stories about these uncanny things that afford immense entertainment for those around him. But there is one idea that has grown into Jerry’s brain and is now part of it, resisting the effects or ridicule, laughter, argument, or explanation. He firmly believes that the White House is haunted by the spirits of all the departed Presidents, and, furthermore, that his Satanic majesty, the devil, has his abode in the attic. He cannot be persuaded out of the notion, and at intervals he strengthens his position by telling about some new strange noise he has heard or some additional evidence he has secured.”

Turns out that the noises in the attic were made by rats and the story of the devil was a ruse devised to keep young Nellie Grant and her girlfriends from playing up there. When McKinley was mortally wounded while standing in a receiving line at an exposition in Buffalo, it was Smith who first announced it in the White House by shouting the news down a White House stairwell, “The President is shot!”

Sadly, Smith was saddled with the social mores and ignorance of his era. Some members of the press derisively called Smith, a Civil War veteran with an inside track to his country’s chief executive, “Possum Jerry” and “Uncle Jerry” or caricaturized him as a “faithful old servant” and “Uncle Tom.” What was never in dispute was Smith’s grace, manners and deferential self-deprecating sense of service. Although highly intelligent, when quoted in newspapers, Smith always spoke with an overly exaggerated dialect. In one example found in a D.C. newspaper story about White House ghosts, Smith describes his communications with the deceased benefactor, President U.S. Grant as: “I done shore ’nuff hear de gin-al’s voice. I done shore ’nuff hear it jes de same as ef it was in dis room, so strong an’ powerful.”

Along the way, Smith’s close relationships with some of the Presidential Families added to his legend. For U.S. Grant’s wife Julia, Smith accompanied the First Lady on her rounds of daily “calls,” a popular tradition in Washington for several decades. Dressed in his finest navy blue uniform with silver trim, it was his responsibility to help the First Lady from the carriage and escort her to the door of whichever home she was visiting. If the lady was “at home,” he would stand by until Mrs. Grant was ready to leave and then escort her back to the carriage. If the lady was not “at home,” Jerry would take Mrs. G’s calling card from a silver case, and leave it with whoever answered the door.

Kind-hearted Julia Grant took a maternal interest in all the White House servants, paying special attention to Jeremiah. During the Grant’s eight years in the White House (1869-1877), real estate prices in the District were low, and affordable housing was available for the poor and minority citizens of Washington. Julia strongly advocated to her servants that they purchase houses as an investment for their golden years. At first, Smith resisted Mrs. Grant’s urging, and she is said to have scolded him, adding that if he did not make arrangements to purchase a house immediately, she would buy one for him, and garnish his monthly wages to pay for it. The result? Jerry bought a house.

There is a well-known story about Smith and First Lady Frances Cleveland, about to depart the White House following Grover Cleveland’s first term loss to Hoosier Benjamin Harrison. On March 4, 1889, as Mrs. Cleveland departed her White House home, she told the doorman to “be sure to keep everything just the same for us when we come back.” When Smith asked the First lady when she would be back, she replied “four years from today.” Sure enough, Grover Cleveland defeated “Lil Ben” Harrison in a rematch and she returned to the White House on March 4, 1893. By then, Smith was such a fixture at the Executive Mansion that several members of President Grover Cleveland’s cabinet attended the celebration of his 25th (Silver) wedding anniversary at his home in 1895. On the couple’s special day, Jerry completed his doorman duties as usual, including lowering the flag, and quietly disappeared for a small celebration only to be surprised by the White House delegation arriving to celebrate with the couple.

According to Crook, “And to that home, that evening, wended a procession of dignitaries such as never before had graced its precincts. Everyone who came to the White House during Jerry’s service there of nearly a quarter of a century, knew the old man, and thoroughly liked him. So great was the general regard, that not merely clerks and assistant secretaries went to his silver wedding, but one carriage after another drove up to his door, containing Cabinet Officers and members of the Diplomatic Corps, sending in to him and his wife some personal gift appropriate to the occasion.” A pile of silver dollars were left on his table as tribute. Jerry was the envy of all his neighbors.

During the McKinley administration, Jerry Smith’s title was the “Official Duster” at the White House because it was less physically demanding and stressful. He retired due to infirmity in 1904 during Theodore Roosevelt’s administration. Months later, shortly before Jerry’s death by throat cancer, TR visited the beloved “duster” at his home and sat with him for a while. It was same little house that Julia Grant had insisted that he purchase all those years before.

When Smith passed away at age 69 in 1904, his Washington, D.C. obituary called him “the best gentility that democracy has produced.” A Los Angeles Times obituary noted, “He was not favored by position, for he was the dustman and the charman; but his dignity and his courtesy made him the most conspicuous and the most liked servant in the place. . . . He was not born to live a life of obscurity, for with dust broom he was as dignified in his bearing as a king on his throne. . . . For more than a quarter century he held his place, and the White House was more changed by his disappearance than by the architects who remodeled it.”

Luckily one photo survives picturing Jerry in his prime. Taken by Frances Benjamin Johnston in 1889, Jerry is posed wearing a full-length white apron, white jacket, plaid necktie, and dark skull cap. Smith stands on the North Portico of the White House smiling sweetly for the camera, the thumb of his left hand tucked inside the apron, his right hand holds his ever-present feather duster at a jaunty 45-degree angle. Although perhaps viewed at the time as the perfect illustration of domestic servitude at the highest level, Jerry Smith’s self-confidence, dignity, and authority dominate the pose. So, whatever one thinks about the ghosts of the White House (Abraham Lincoln in particular), Smith was certainly a memorable character at the White House. And one helluva storyteller.

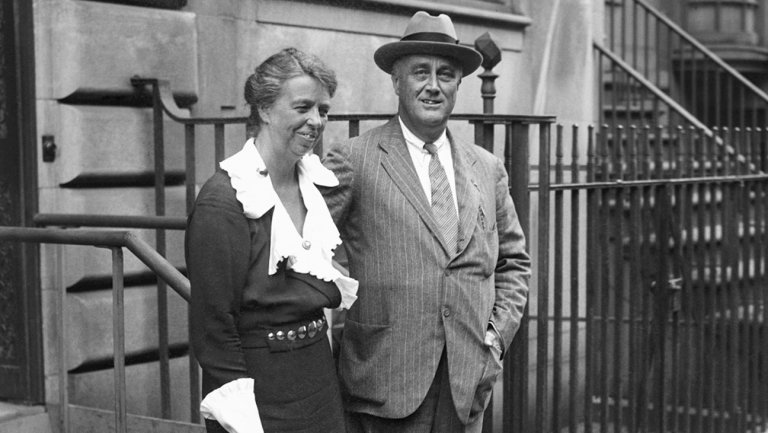

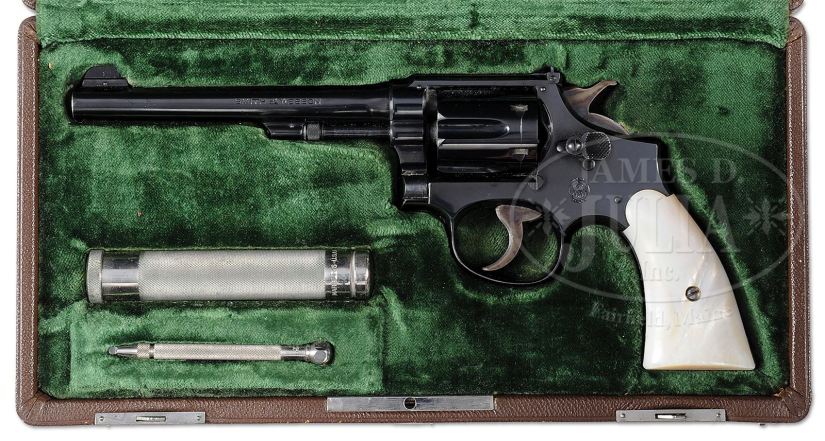

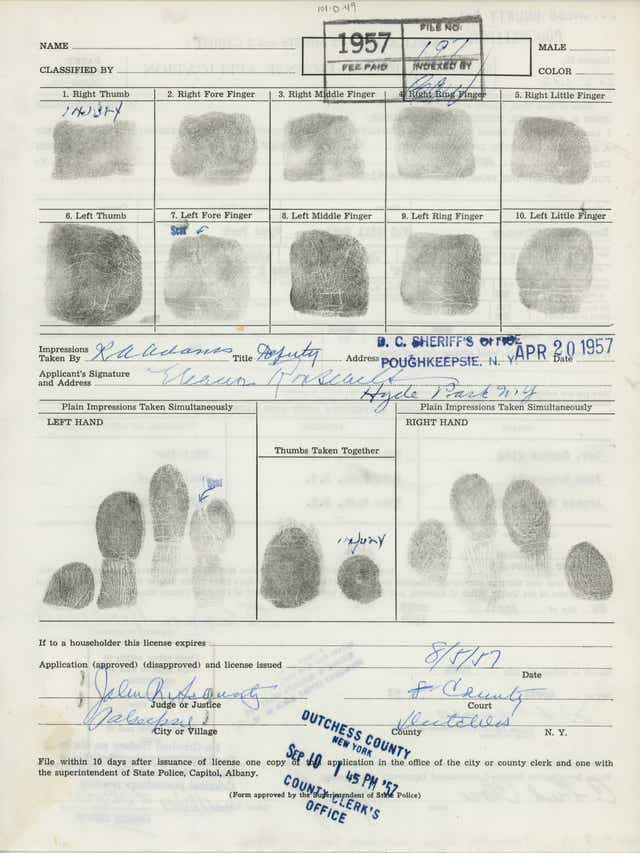

Oh, and by the way, Eleanor Roosevelt, the First lady of the world, icon of liberalism, fighter for civil rights, champion of the poor and marginalized and powerful advocate for women’s rights was a gun owner. Yes, Eleanor Roosevelt, mother of six, grandmother to twenty, was packing heat. Her application for a pistol permit in New York’s Dutchess County can be found at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in Hyde Park. With debate raging around the nation about gun control and Second Amendment rights, the fact that one of the icons of the Democratic womanhood not only owned a gun, but carried it for protection, may come as a surprise.

Oh, and by the way, Eleanor Roosevelt, the First lady of the world, icon of liberalism, fighter for civil rights, champion of the poor and marginalized and powerful advocate for women’s rights was a gun owner. Yes, Eleanor Roosevelt, mother of six, grandmother to twenty, was packing heat. Her application for a pistol permit in New York’s Dutchess County can be found at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in Hyde Park. With debate raging around the nation about gun control and Second Amendment rights, the fact that one of the icons of the Democratic womanhood not only owned a gun, but carried it for protection, may come as a surprise.

The application was processed by the Dutchess County Sheriff’s Office and signed by then-Sheriff C. Fred Close. It included a photo of Eleanor Roosevelt wearing a hat, fur stole and double strand of pearls. The reason for the pistol, according to Eleanor Roosevelt’s application, was “protection.” The timing of the pistol permit coincided with Eleanor Roosevelt’s travels throughout the South-by herself-in advocacy of civil rights. Those trips prompted death threats.

The application was processed by the Dutchess County Sheriff’s Office and signed by then-Sheriff C. Fred Close. It included a photo of Eleanor Roosevelt wearing a hat, fur stole and double strand of pearls. The reason for the pistol, according to Eleanor Roosevelt’s application, was “protection.” The timing of the pistol permit coincided with Eleanor Roosevelt’s travels throughout the South-by herself-in advocacy of civil rights. Those trips prompted death threats. Viewed from the perspective of 21st century politics, where Republicans and Democrats have lined up on opposing sides of the gun control debate, Eleanor Roosevelt’s pistol offers a fresh take on the ongoing debate over the rights of gun owners, the Democrats who want to curtail them and the Republicans who want to expand them.

Viewed from the perspective of 21st century politics, where Republicans and Democrats have lined up on opposing sides of the gun control debate, Eleanor Roosevelt’s pistol offers a fresh take on the ongoing debate over the rights of gun owners, the Democrats who want to curtail them and the Republicans who want to expand them.

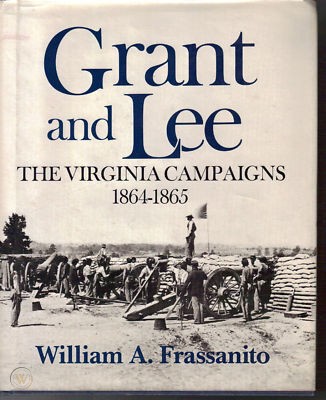

Needless to say, I was pleased with my visit to and pleasantly reminded how invaluable places and people like these are to the preservation and education of history. After the ACHS helped fill in some blanks in my research, I turned my attention to author Bill Frassanito. He is intensely private, yet unassuming and modest in demeanor. Although an author by trade and historian by nature, Mr. Frassanito has the soul of a teacher.

Needless to say, I was pleased with my visit to and pleasantly reminded how invaluable places and people like these are to the preservation and education of history. After the ACHS helped fill in some blanks in my research, I turned my attention to author Bill Frassanito. He is intensely private, yet unassuming and modest in demeanor. Although an author by trade and historian by nature, Mr. Frassanito has the soul of a teacher.

When asked what first drew him to Gettysburg, he explains, “My first trip to Gettysburg was in 1956 when I was nine years old, and I was just awed by all the monuments, cannons and stuff. I started my research when I was a kid and much of the research for Journey in Time was done when I worked it into a Masters thesis (he is a proud Gettysburg College alum). “When you went to Gettysburg College, I was the high school class of ’64, college class of ’68, at that time all the male students had to take either phys ed or ROTC for two years, after that you made the decision whether you continued on to advanced ROTC, then you were a part of the Army and you got paid. From there you are committed to, after graduation, serving for two years as a second lieutenant, then on to grad school.”

When asked what first drew him to Gettysburg, he explains, “My first trip to Gettysburg was in 1956 when I was nine years old, and I was just awed by all the monuments, cannons and stuff. I started my research when I was a kid and much of the research for Journey in Time was done when I worked it into a Masters thesis (he is a proud Gettysburg College alum). “When you went to Gettysburg College, I was the high school class of ’64, college class of ’68, at that time all the male students had to take either phys ed or ROTC for two years, after that you made the decision whether you continued on to advanced ROTC, then you were a part of the Army and you got paid. From there you are committed to, after graduation, serving for two years as a second lieutenant, then on to grad school.”

Bill’s collecting interests are not solely confined to Gettysburg. “All of my stuff is going to the Adams County Historical Society. It will be called the Frassanito collection. Including all my stuff that goes beyond Gettysburg and Adams County. My interest in military history includes World War I and Franco Prussian war, it’s very expansive.” Mr. Frassanito’s interest in all things military came when he saw the 1956 movie “War and Peace” starring Audrey Hepburn and Henry Fonda and, he states, “from that time on I’ve been fascinated by Russian history including the Crimean War” (October 1853 to February 1856 in which the Russian Empire lost to an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, Britain and Sardinia).

Bill’s collecting interests are not solely confined to Gettysburg. “All of my stuff is going to the Adams County Historical Society. It will be called the Frassanito collection. Including all my stuff that goes beyond Gettysburg and Adams County. My interest in military history includes World War I and Franco Prussian war, it’s very expansive.” Mr. Frassanito’s interest in all things military came when he saw the 1956 movie “War and Peace” starring Audrey Hepburn and Henry Fonda and, he states, “from that time on I’ve been fascinated by Russian history including the Crimean War” (October 1853 to February 1856 in which the Russian Empire lost to an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, Britain and Sardinia).

Bill continued, “I fortunately survived Vietnam and I put it (his book research) all together when I got out of the Army. I tried to get a job in the museum field but the book took off when I signed with one of the top publishers, Charles Scribner’s. It was later picked up for the Book-of-the-Month club. That became the first of seven books on Civil War photography. I spent eight years and eight months on that project.” One of Bill’s most important discoveries was the “Slaughter Pen” near Devil’s Den. Bill’s book included detailed maps. Bill explains, “The whole purpose of the book was to enable people to re-experience standing where the photographer was. One of the questions I often get is why I don’t update the modern photographs. I’ll never do that as I see them as sort of a time capsule in themselves and I want people to know what the battlefield looked like when I spent five years looking for these spots.”

Bill continued, “I fortunately survived Vietnam and I put it (his book research) all together when I got out of the Army. I tried to get a job in the museum field but the book took off when I signed with one of the top publishers, Charles Scribner’s. It was later picked up for the Book-of-the-Month club. That became the first of seven books on Civil War photography. I spent eight years and eight months on that project.” One of Bill’s most important discoveries was the “Slaughter Pen” near Devil’s Den. Bill’s book included detailed maps. Bill explains, “The whole purpose of the book was to enable people to re-experience standing where the photographer was. One of the questions I often get is why I don’t update the modern photographs. I’ll never do that as I see them as sort of a time capsule in themselves and I want people to know what the battlefield looked like when I spent five years looking for these spots.” Frassanito notes that the publication of that photo started a search that is still going on 44 years later. There have been two dozen sites that have been suggested as the site of the photograph. “When people make their discoveries it becomes a religious experience. Every one of those sites has major problems. As far as I’m concerned I don’t want to see a faulty location declared the site and have the search end. That’s the biggest mystery for Civil War photography at Gettysburg. And I’m hoping that one day a pristine 1863 version of the original stereoview or negative surfaces.”

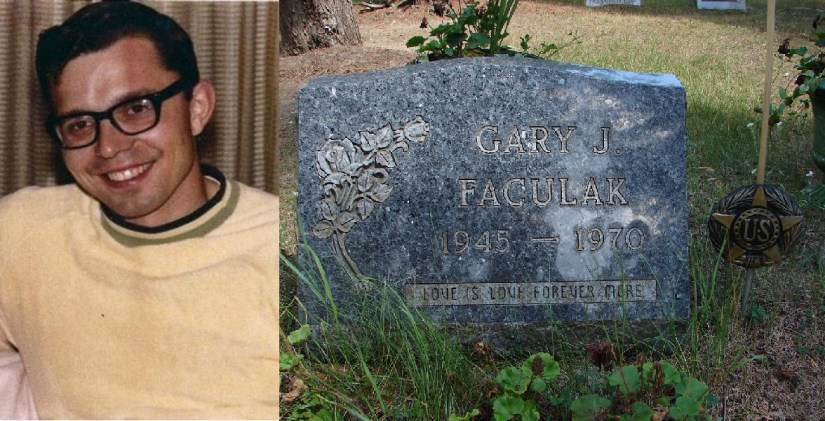

Frassanito notes that the publication of that photo started a search that is still going on 44 years later. There have been two dozen sites that have been suggested as the site of the photograph. “When people make their discoveries it becomes a religious experience. Every one of those sites has major problems. As far as I’m concerned I don’t want to see a faulty location declared the site and have the search end. That’s the biggest mystery for Civil War photography at Gettysburg. And I’m hoping that one day a pristine 1863 version of the original stereoview or negative surfaces.” “I lived about 2 miles away in kind of a slum area of Saigon, it was a hotel we rented from the Vietnamese called Horn Hall. On the main floor was a narrow lobby, and there were two shifts requiring a duty officer, you had to spend six hours just sitting there. You had a pistol and if anything happened, you were in charge. One of the shifts was midnight to six. On the 16th of December 1970 I was assigned night duty at MACV headquarters so my name was removed from the night duty at Horne Hall. Later, we got a phone call that a bomb had gone off that night at Horne Hall and the Lieutenant on duty was instantly killed. And I realized that had I been sitting there, all of my discoveries would have gone with me. And these classic photos of the 24th Michigan and 1st Minnesota would still be misidentified.”

“I lived about 2 miles away in kind of a slum area of Saigon, it was a hotel we rented from the Vietnamese called Horn Hall. On the main floor was a narrow lobby, and there were two shifts requiring a duty officer, you had to spend six hours just sitting there. You had a pistol and if anything happened, you were in charge. One of the shifts was midnight to six. On the 16th of December 1970 I was assigned night duty at MACV headquarters so my name was removed from the night duty at Horne Hall. Later, we got a phone call that a bomb had gone off that night at Horne Hall and the Lieutenant on duty was instantly killed. And I realized that had I been sitting there, all of my discoveries would have gone with me. And these classic photos of the 24th Michigan and 1st Minnesota would still be misidentified.”

Our tour guide explains, “The house had been in the Peter Baker family since 1847.” As a youngster, Dean listened to stories under the old tree that is still there near the house. He continues, “This is where the original guides used to gather under the tree and smoke cigars and drink a little whiskey. The Baker boys were bachelors and always had time to tell stories.” Dean has an encyclopedic knowledge of the battle, but also has personal stories told to him by the legendary figures of this battlefield town. As a youngster, Dean recalls visits by “Pappy Rosensteel who had a huge collection of battlefield relics that he took me to on many occasions.” George D. Rosensteel (1884-1971) had a fantastic lifetime collection of battle relics and displays, including the interpretive Battle of Gettysburg map, acquired by the National Park Service for use in the Gettysburg National Military Park museum and visitor center from 1974-2008. “But they didn’t get it all,” Dean says, “They didn’t get it all.”

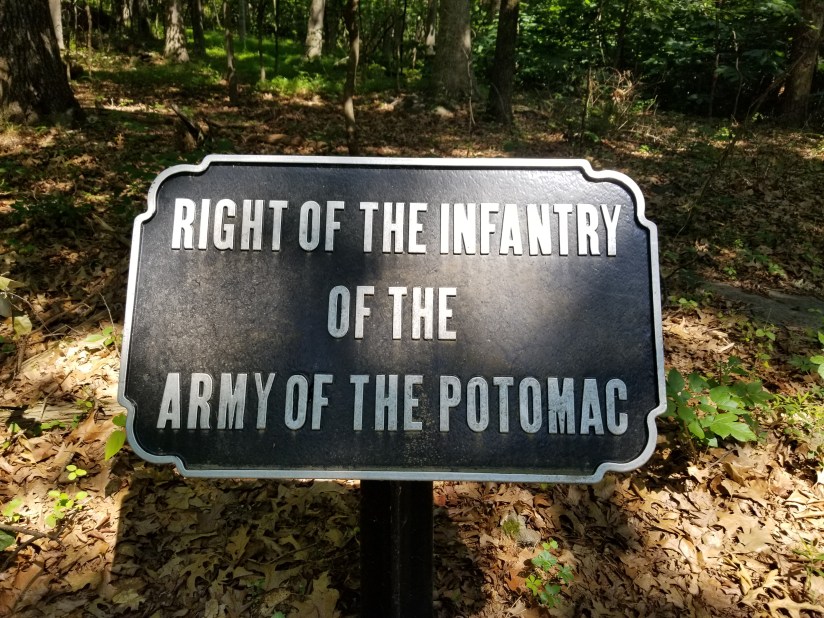

Our tour guide explains, “The house had been in the Peter Baker family since 1847.” As a youngster, Dean listened to stories under the old tree that is still there near the house. He continues, “This is where the original guides used to gather under the tree and smoke cigars and drink a little whiskey. The Baker boys were bachelors and always had time to tell stories.” Dean has an encyclopedic knowledge of the battle, but also has personal stories told to him by the legendary figures of this battlefield town. As a youngster, Dean recalls visits by “Pappy Rosensteel who had a huge collection of battlefield relics that he took me to on many occasions.” George D. Rosensteel (1884-1971) had a fantastic lifetime collection of battle relics and displays, including the interpretive Battle of Gettysburg map, acquired by the National Park Service for use in the Gettysburg National Military Park museum and visitor center from 1974-2008. “But they didn’t get it all,” Dean says, “They didn’t get it all.” We are standing at the base of Wolf Hill near Rock Creek on the far right of the Union Army infantry line; the sounds of traffic whizzing by us on the Baltimore Pike, but it feels like we have traveled back in time. Dean leads us up the slope, we walk about a football field’s length away as he stops in some shady spot, relights his pipe, and explains about cattle grazing in the woods or points out where soldiers were once temporarily buried. This amazing octogenarian halts often, not for his sake but for ours. He climbs these slopes with the agility of a man half his age. He is not winded, but we are.

We are standing at the base of Wolf Hill near Rock Creek on the far right of the Union Army infantry line; the sounds of traffic whizzing by us on the Baltimore Pike, but it feels like we have traveled back in time. Dean leads us up the slope, we walk about a football field’s length away as he stops in some shady spot, relights his pipe, and explains about cattle grazing in the woods or points out where soldiers were once temporarily buried. This amazing octogenarian halts often, not for his sake but for ours. He climbs these slopes with the agility of a man half his age. He is not winded, but we are. As we reach the entrance to Lost Avenue, Dean explains with a sweep of his hand, “This was an orchard at the time of the battle, the bodies of many soldiers were buried in rows right over there.” Former resident Cora Baker’s (1890-1977) grandmother told how, after the battle as the bodies were picked up for reburial, “the grass just quivered with lice and bugs where they laid and when the soldiers would roll up their bedrolls in the morning, the grass was alive with lice and bugs from the bodies of the living soldiers as well.”

As we reach the entrance to Lost Avenue, Dean explains with a sweep of his hand, “This was an orchard at the time of the battle, the bodies of many soldiers were buried in rows right over there.” Former resident Cora Baker’s (1890-1977) grandmother told how, after the battle as the bodies were picked up for reburial, “the grass just quivered with lice and bugs where they laid and when the soldiers would roll up their bedrolls in the morning, the grass was alive with lice and bugs from the bodies of the living soldiers as well.” Upon entering Lost Avenue, Dean explains that General Neill was sent here to guard the rear flank of the Union Army and, most importantly, to protect the Baltimore Pike. Dean states, “When I was a boy I used to visit Lost Avenue with Arthur Baker (1893-1970), who as a lad had walked the fields with the old soldiers that visited the property and actually fought over this ground. Arthur would go and grab a bayonet, left here after the battle, from one of the farm buildings. He’d attach it to his walking stick, hide behind the stone wall and charge out screaming the Rebel Yell.”

Upon entering Lost Avenue, Dean explains that General Neill was sent here to guard the rear flank of the Union Army and, most importantly, to protect the Baltimore Pike. Dean states, “When I was a boy I used to visit Lost Avenue with Arthur Baker (1893-1970), who as a lad had walked the fields with the old soldiers that visited the property and actually fought over this ground. Arthur would go and grab a bayonet, left here after the battle, from one of the farm buildings. He’d attach it to his walking stick, hide behind the stone wall and charge out screaming the Rebel Yell.” Dean maintains the avenue. “The park service never comes out here. Most of the guides have never been out here. The only one I’ve ever seen up here was Barb Adams.” Lost Avenue is the last section of the battlefield that looks exactly as it did when the soldiers fought, and died, here. Dean further explains, “Monuments were set on grass lined strips with no thought of ever paving them. The roads you know now were paved much later. Lost Avenue is the last “pristine section” of unpaved roadway. The 40 foot wide strip is lined by the original stone fence that the 2nd Virginians & 1st North Carolinians fought behind. It was made of field stones picked up by farmers over the years and predates the battle. The second stone wall, the 1895 section, was built later after Sickles took over.”

Dean maintains the avenue. “The park service never comes out here. Most of the guides have never been out here. The only one I’ve ever seen up here was Barb Adams.” Lost Avenue is the last section of the battlefield that looks exactly as it did when the soldiers fought, and died, here. Dean further explains, “Monuments were set on grass lined strips with no thought of ever paving them. The roads you know now were paved much later. Lost Avenue is the last “pristine section” of unpaved roadway. The 40 foot wide strip is lined by the original stone fence that the 2nd Virginians & 1st North Carolinians fought behind. It was made of field stones picked up by farmers over the years and predates the battle. The second stone wall, the 1895 section, was built later after Sickles took over.”