Part I

Original Publish Date September 18, 2025.

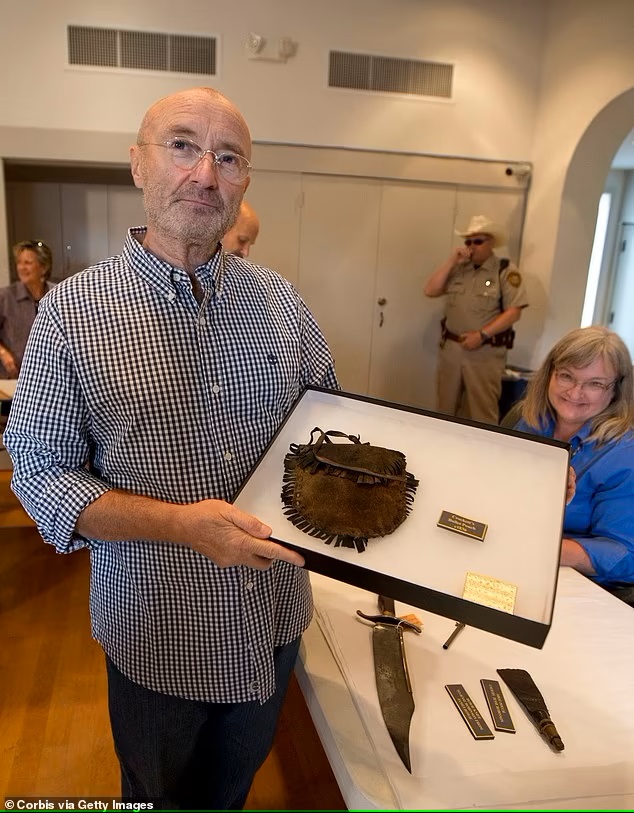

As many of you who have read my columns over the past two decades will recall, I am a collector. Many of my columns center around collectibles, some valuable, some historic, and some for sheer folly with no lasting value other than a momentary nostalgic smile. I often visit regular antique shows, events, and roadside markets looking for whatever I can find. I recently visited a regular haunt and once again found my hands inside of boxes containing an assortment of papers and bric-a-brac from a lifetime ago. Sometimes, I run across something serendipitously, as if it was placed there specifically for me to find; one step away from the trash heap.

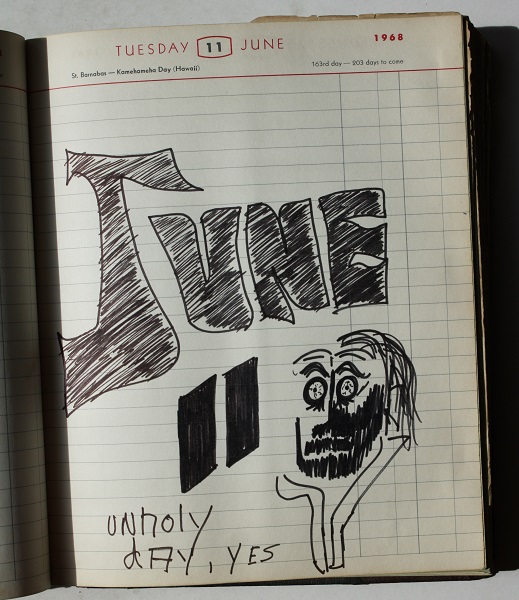

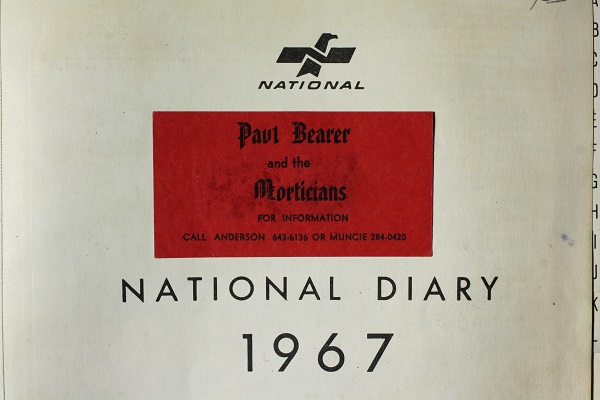

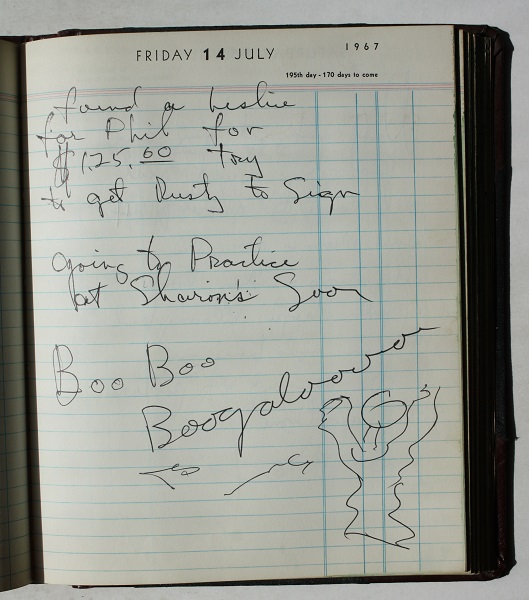

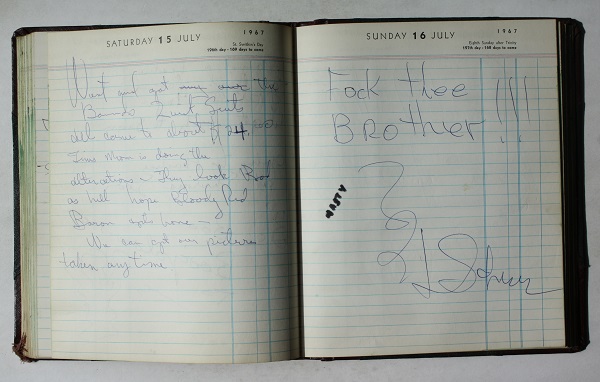

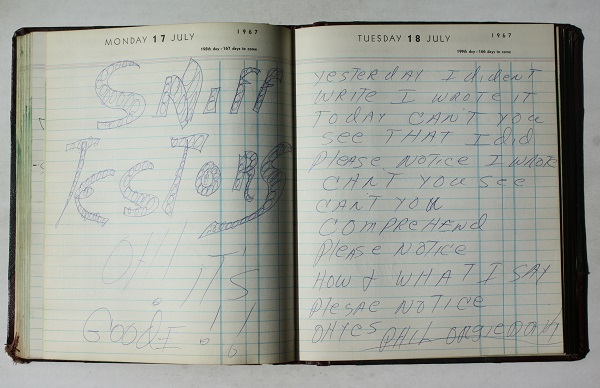

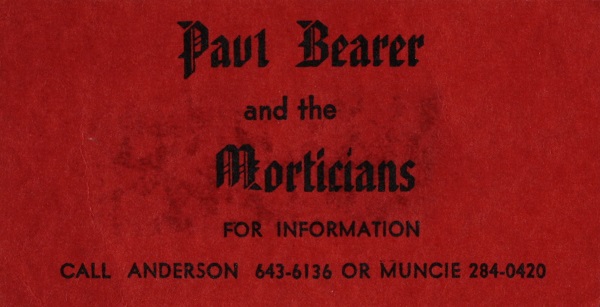

In this box, there were two 8×10 thick & heavy leather-bound books, each titled “National Diary”, although they have 1967 & 1968 cover dates, I believe they’re from 1968 & 1969 (likely a frugal “clearance” purchase by a struggling band not hung up on the concept of time, man). When I opened the initial book, the first thing I saw was a bright red business card pasted to the top of this page, emblazoned “Paul Bearer and the Morticians” with Anderson & Muncie, Indiana phone numbers inset. I quickly flipped through the first few pages to see what it was, as a wide-eyed smile slowly crept across my face. Not the best poker face, I told myself as I slammed the book closed and decided that these were going home with me. There they sat beside my “writing chair” waiting for me to devour them. Life gets in the way sometimes, so it took me a minute to get there. Oh, I would occasionally pick one of them up, flip through the pages, and whet my curiosity whistle, until I finally had a day to devote to a full read.

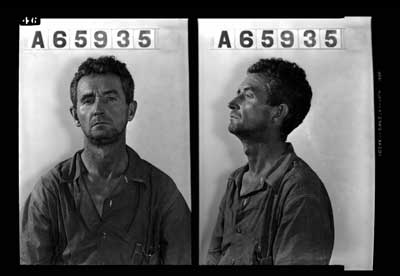

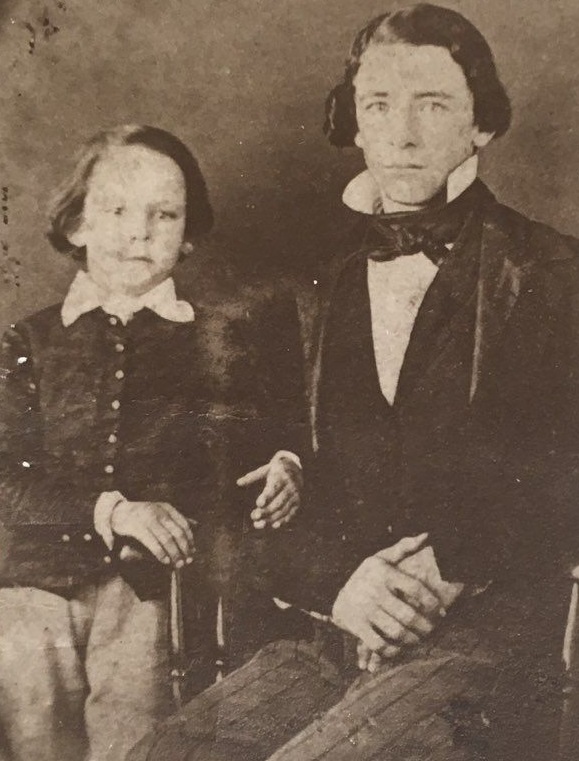

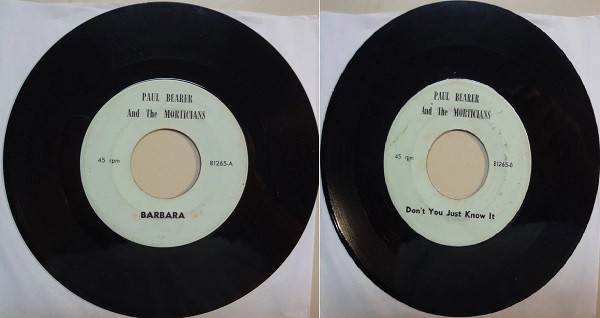

Turns out, what I had accidentally stumbled over was a day-by-day accounting of an Indiana garage band as detailed by one of its members, Larry Scherer, aka Paul Bearer himself! Larry Phillip Scherer was born Sept. 19, 1946, in Anderson and passed away on Jan. 23, 2004, in Greenfield. By all accounts, while growing up, Larry lived an ideal Hoosier childhood. He was active in Cub Scouts and Boy Scouts and played football and Little League baseball. He graduated from Anderson High School in 1964 and later earned his BA and MA in Counseling Psychology from Ball State University. He was the lead singer of the band, Paul Bearer and the Morticians. Not a lot is known about this band. A few references can be found on the net, including a 45 rpm single and a single publicity shot of the 5-man band posed around a hearse in a cemetery surrounded by their instruments. The single’s A-side is a song called “Barbara,” and the B-side is “Don’t You Just Know It.”

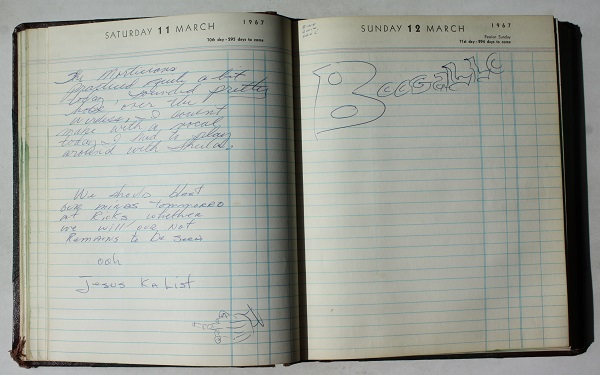

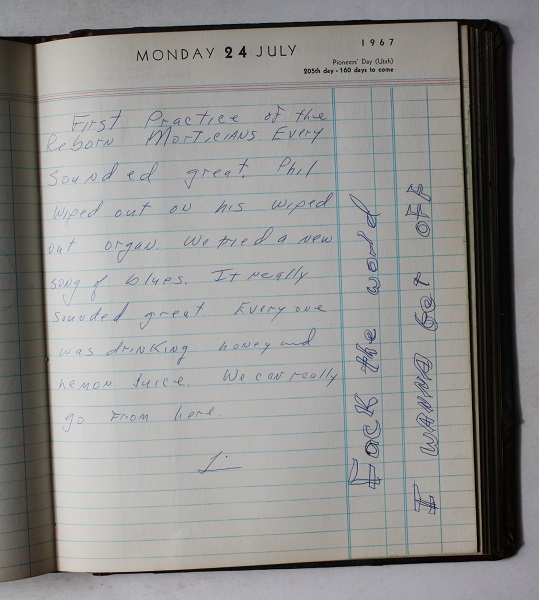

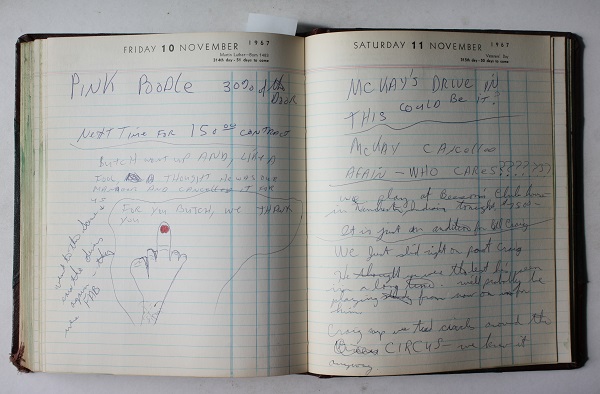

Each book begins & ends with a calendar page, both jumbled by hurried circles, arrows, and scribbles denoting sporadic gigs every week. Flipping through the pages, one can almost feel the high hopes of the band melting away during those first formative winter months. The entry for January 1 notes that the band took some publicity photos, which must have boosted their hopeful confidence immensely. Then reality sets in. The pages from January to February are filled with depressing notations of inactivity: “Nothing” and “Nada” on nearly every page, like a road to nowhere. Around Valentine’s Day, things were looking up, but not musically. Feb. 10, “Went to see Paul Revere + the Raiders-they were great-got a tip at where they were staying + buzzed out there. Holiday Inn-Got all their autographs…Jack talked to Mark Lindsay…We should have some great pictures.” On Feb. 17th, “Played at McPherson’s Dance Inn [in Anderson] over 300 showed up, we made $100 clear (about $1,000 today)…Thank God…we each got about $14 per man.”

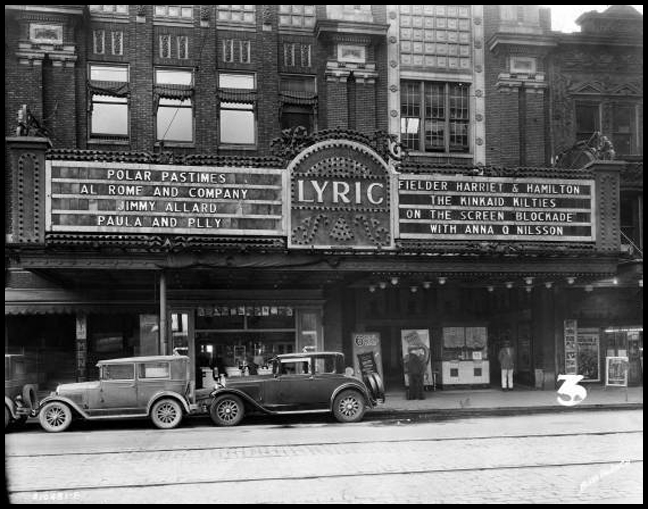

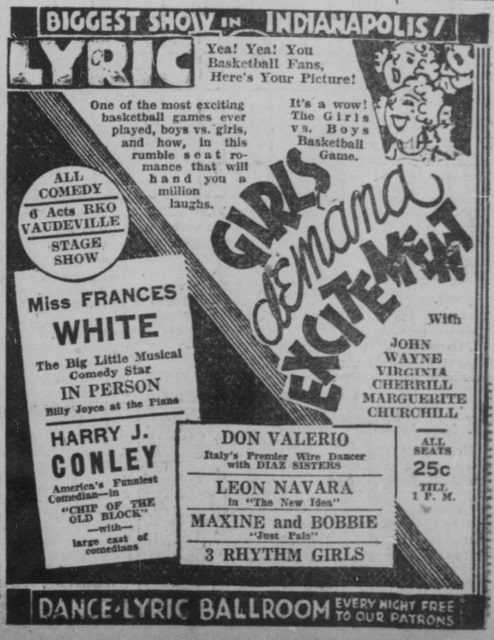

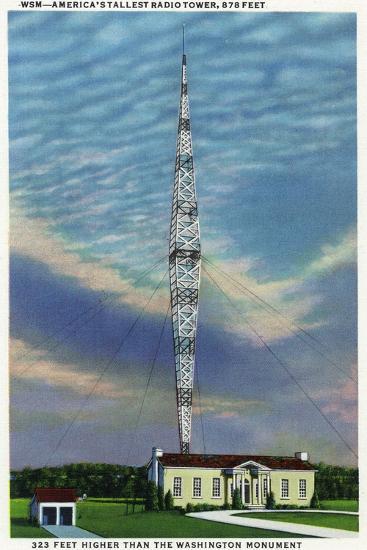

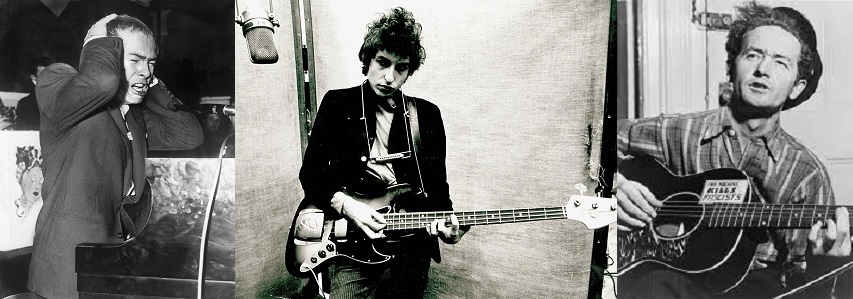

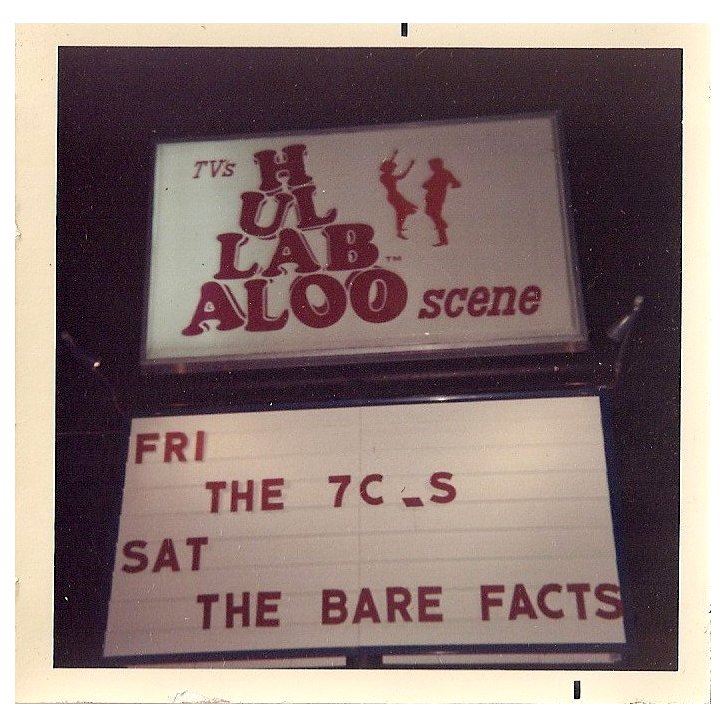

Bolstered by this modest success, the boys begin to practice regularly on original compositions (Town of Evil) and covers (Cream’s “Sunshine of Your Love” and “Outside Woman Blues”) in preparation for a desired gig at a “Hullabaloo”. A Hullabaloo was the franchise name for teen dance clubs spinning off the popular NBC musical variety show of that era. The TV series originated in London and was hosted by The Beatles’ manager Brian Epstein before hopping across the pond to America.

These trademarked “Hullabaloo” nightclubs were usually found near colleges (Ball State, IU, Purdue, Notre Dame, etc.) and larger high schools. On Feb. 27, the band played the Conservation Club in Anderson and received $140. “[We] sounded like a professional group, surprised everyone but me…First time we used Saxophone-sounded real good-going to use it a helluva lot more.” The success of that gig led to an audition for the Teen Time Lounge in Hartford City. March 3: “Notified to play Teen Time Palace…Sounded Great. KIds ate us up. Nothing much happened except some clown busted a $200 glass door. Some girl asked for autographs.” The band was paid $75 and by now Paul Bearer and the Morticians had a set list of 41 songs: “35 good ones-6 stand bys” including covers of the Rolling Stones “Under My Thumb”, Junior Walker’s “Pucker Up Buttercup”, Spencer Davis Group’s “Gimme Some Lovin”, and Wilson Pickett’s “In The Midnight Hour.”

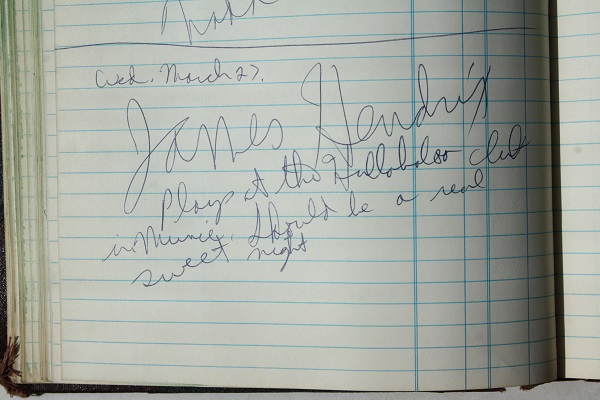

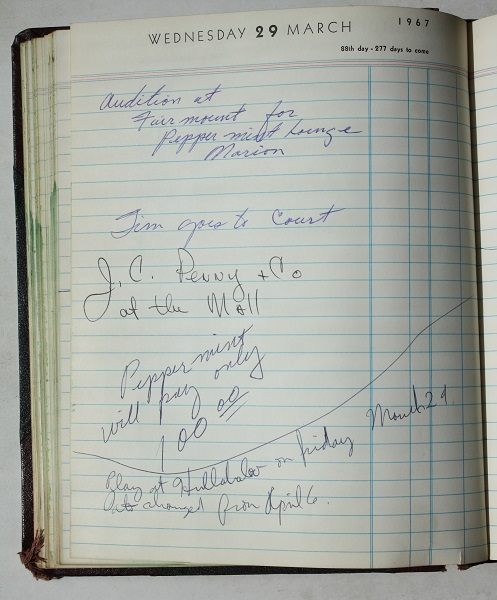

By mid-March, the band was looking ahead to a gig at Anderson’s Peppermint Lounge. March 15, “Tim came over to get some money to finish the coffin-Paid $5.” The Morticians were paid $115; by the time they left the stage, the boys made $7 each after expenses. On March 22, the band hoped to land a $125 gig at the Hullabaloo in Muncie. March 27 entry reads: “James Hendrix plays at the Hullabaloo Club in Muncie.

Should be a real sweet night.” The very next night, the Morticians take the stage. The band is fielding inquiries for gigs at Rensselaer ($115 payout), Hartford City ($50), Fairmount ($100), and Lapel ($85). April 1: “Best critics in Anderson-my friends-said we were whats happening-I agree!! The guys sounded great. I know we can make it to the top-just a matter of time—is on my side, yes it is.” On April 5, the Morticians book a gig to play at the Hullabaloo Club in Dayton, Ohio: for $150. On April 8, the boys again played for Anderson’s Conservation Club. “Blast it was too!! The band finally hit what its worth-a cool 40 beans apiece!! There were 267 kids there-about half sniffen glue-haha. Split the profit.”

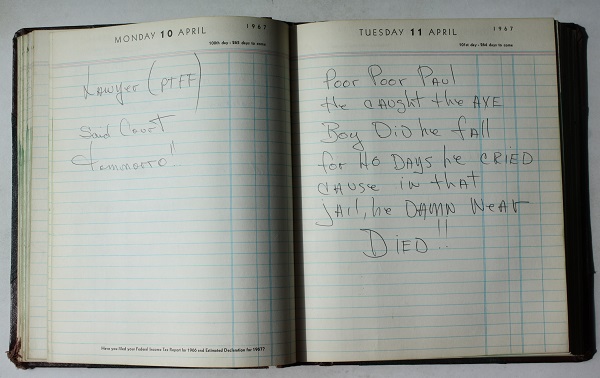

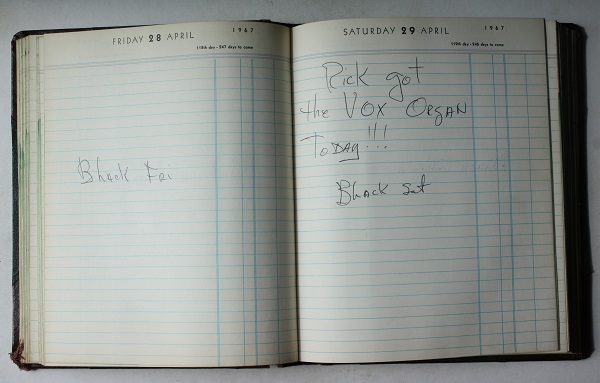

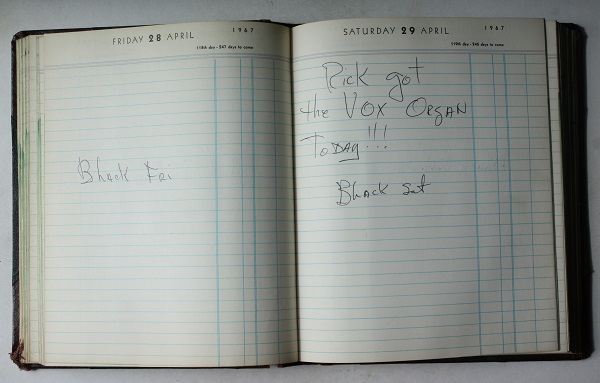

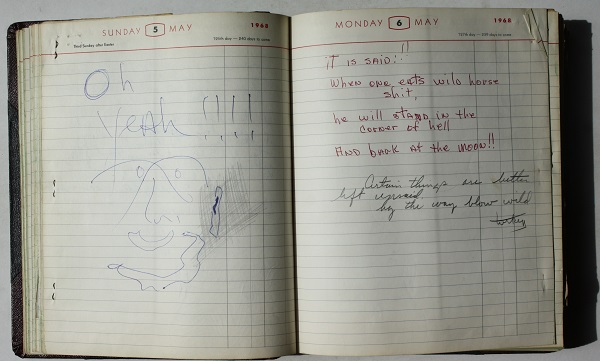

On April 11th, the diary lyrically notes, “Poor, Poor Paul. He caught the axe. Boy, did he fall. For 40 days he cried cause in that jail, he damn near died!!” For the next 40 pages, every day is denoted as “Black Monday, Black Tuesday, Black Wednesday, etc.” On May 20, another lyric, “Oh!! Did you hear what they say. Oh Paul’s out now, and their on their way. Dunt Dunt Dunt Hey!!”

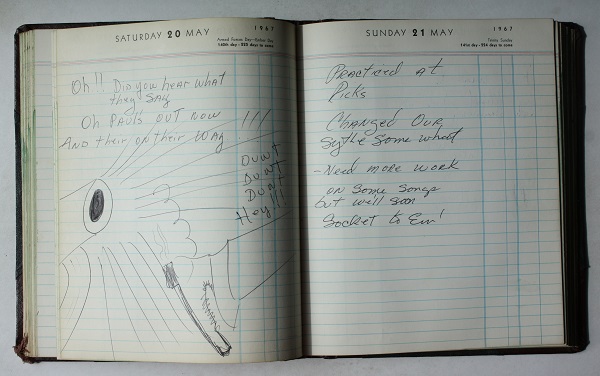

The band starts up again, practicing regularly at “Rick’s”. May 21: “[We] need more work. Changed out style somewhat on some songs but we’ll soon socket to em!” May 26th “Play at Van Buren tonight. (expecting small crowd) We may be surprised, I hope so. I need a good one for a change.”

May 27, “Conservation Club Tonight $100.” On June 5th, the band joins the American Federation of Musicians for $102.50. June 29th, “Practiced at Rick’s house + thusly decided to kick out Rick. One Mortician is buried.” July 7, “Found the band outfits at a Brand X store in Indianapolis. Sweet as hell for a mere 5 beans.” August 6, “Got our publicity pictures taken today at the graveyard in back of North Drive Inn [Anderson] 14 in all. Two sets of clothes. Outta be cold, cold shake cool. Blimey Govnor.” The entry on August 8 is actually the handwritten lyrics to a song: “There is a man from L.A., That is hard to understand. People tell me he’s an uncertain kind. In California where kids blow their mind. He has come to Hoosierland to waste his time. There are two things that he loves, an old truck and a jail to sleep. Some call him little Bo-peep. Since coming to the Midwest, he is always losing his job, because of this he can’t afford my little nest. Maybe someday he’ll be persuaded to stay around, he’ll be downgraded. No home to go to weep or food to eat. This is a man from L.A. who sleeps in the hay. He is a different brand, but now a lighting man.”

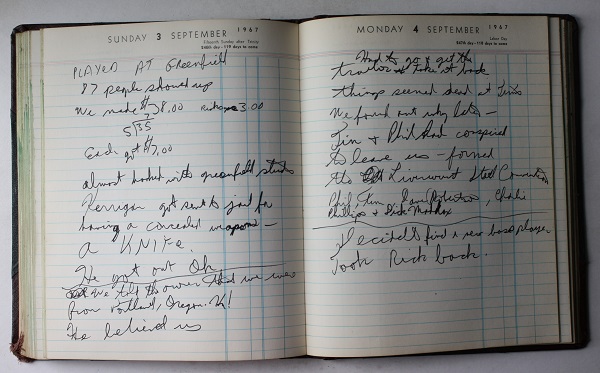

August 14th, another song, not much better than the first: “Hey Baby, why don’t you love me anymore. Hey Baby, I been here all alone eh. You know I love you, But you don’t realize, you will love me, when I look in your eyes. Oh, you got to love me, baby, then love me all the time. In the morning, in the evening, in the summer, in the winter, you gotta love me. Hey baby, I’ll buy a house + settle down. Hey, ask your mom, tell her I love you. If there’s any doubt, Baby believe me, everything I say is true. If you don’t love me, I’ll try to be true. You got to love me in the bathroom, in the kitchen, in the basement, in the sink, in the backyard. You gotta love me.” August 17, “Practided! Worked on a couple new songs. Two friends of Phil’s who own the Acid Land nightclub came to watch us. Played a lot of Psychedelic stuff.” August “Paul went to labor at the Delco Remy Salt Pits…Won’t last long.” September 3: “Played at Greenfield. 87 people showed up. We made $38. Each got $7. Tim + Phil conspired to leave us-formed the Liverwurst Steel Convention [band].” By mid-month, the Morticians were practicing new songs, mostly by The Who: “Whiskey Man” & “Pictures of Lily”.

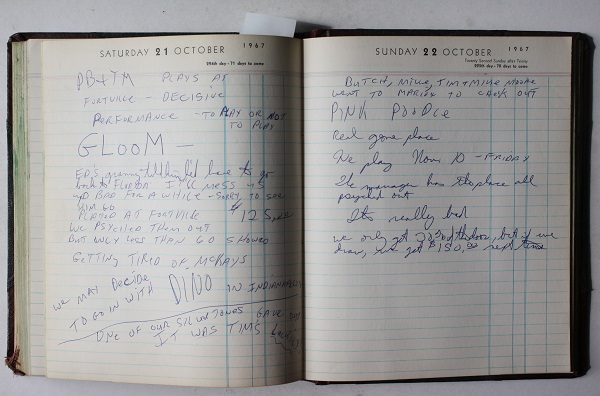

The band booked a Sept. 30th gig for $125 at McKay’s Drive-In nightclub known as the “Psycadelic Sounds at The Place” on Highway 67 in Fortville, after which they were signed as the “House Band”. October 1st, “Played at Fortville, made $2 per. If fortune doesn’t straighten up, we’re going to drop McKay. Not enough crowd…Learned two more songs: “I Need You”-By The Beatles + “Tired Of Waiting For You”-Kinks.” Oct. 18th: “We really psyched out on Fortville. I can’t explain. Had Better Be Ready.” Oct. 21: “Fortville-Decisive Performance-To Play or Not to Play. GLOOM. We psyched them out but only less than 60 showed. Getting tired of McKay’s.” Nov. 4, “Dance scheduled for McKay’s but he screwed us up again + cancelled the dance cause his roof wasn’t fixed.” Nov. 8, “We play at the Beeson Clubhouse Country Club [in Winchester] on Saturday Next. Nice Place. We get $75. Auditioned for the Hullabaloo Club in Muncie tonight. They thought we were BEAUTIFUL!! They dug the Jimi Hendrix stuff we played.” Nov. 11: “McKay’s Drive In. This could be it. McKay cancelled again-who cares??? We played at Beeson’s Clubhouse in Winchester, Indiana tonight. $75.” Nov. 15: “We found out the WHO will be in Muncie on Thanksgiving night + there’s a chance we might play alongside them. It may all depend on our performance at the barn Saturday night.” Nov. 23-Thanksgiving day. “The Who played at the new barn. All of us went to see them-they were greater than ever. We got to talk to Pete Townshend a little bit-he was really cool. Mike got some great pictures.”

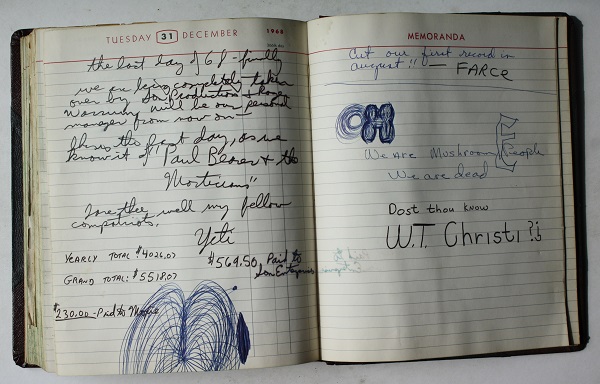

By December, the Morticians set list included 39 songs including JImi Hendrix “Hey Joe” (which they performed twice back-to-back), “Give me some lovin'”, “I can’t explain”, “Mickey’s Monkee”, “Bring it on home to me”, “Louis Louis”, “Money”, “Little Latin Lupe Lu”, “Hold On”, “We gotta get out of this place”, “Purple Haze”, “Fire”, “Foxey Lady”, “MIdnight Hour”, “The Letter”, “House of the Rising Sun”, “I’ve been loving you too long”, “Lady Jane”, and an intriguing original song titled “Ban the Egg.” On Christmas Eve, the boys “Played at Winchester for $75. The crowd dug us bad. Michael Eddie screwed up Purple Haze 3 times that night-Used Pete Townshend’s guitar strap.” The Morticians practiced but did not gig for the remainder of the year, resulting in the Dec. 31st entry: “A very dull New Year’s Eve Indeed.” Year-end receipts totaled $1899.50 (just under $20,000 today), averaging out to $70.70 per gig. Split between a rotating lineup of five musicians per night, it doesn’t take a mathlete to figure out that none of these guys could quite their day jobs.

Paul Bearer and the Morticians-An Indiana Garage Band Story.

Part II

Original Publish Date September 18, 2025.

In part I of this article, I detailed one of my latest “Finds”, a 1968 diary from the leader of a 1960s Anderson, Indiana garage band known as “Paul Bearer and the Morticians.” I love that it landed in my lap just before the official spooky season in Irvington commences. I wanted to share it with you, the readers, because I thought that it might stir the chords of mystic memory for other Circle City hippy kids like myself.

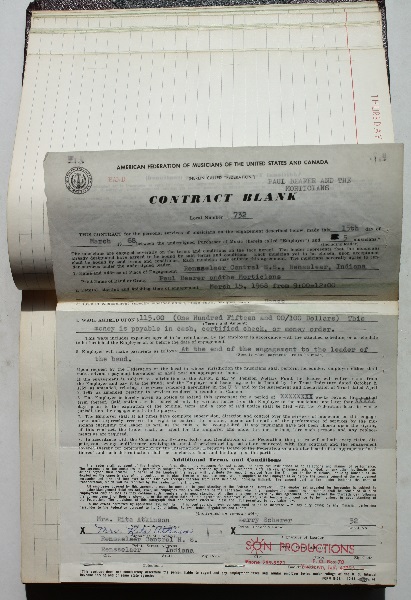

Jan. 13 [1969]: Played at the Loft in Muncie for a mere $75. A real good crowd showed up + there were only a few meager fights. Jan. 25: “Conservation Club [Anderson]- “Not too good of a crowd. We only made $47.50.” Jan. 27: “We played at Winchester, Ind. for $85. That’s all I’m going to say!!” On Feb. 17th, “Played at McPherson’s Dance Inn [in Anderson] over 300 showed up we made $100 clear (about $1,000 today)…Each Poison (sic) got $14 apiece.” By March, the band was looking more official than before. This second diary book includes a few of the original typed contracts between the venues and the band, all signed by Larry Scherer as the band’s representative. March 15th, 1968, is for a gig at Rensselaer High School for $115. The diary entry reads: “It was a hick dance at a school, but they liked us. Wild night in the motel there-almost got kicked out. We also had a lot of car trouble-flat tire, breakdown, etc etc.” Another contract is for the Muncie Hullabaloo Club on Kilgore near Yorktown. It netted $125 for the band and stipulates that a fee of $25 “per half hour late starting” will be enforced. The band played two sets for a “real good crowd. Our first set was a little ill, but we smoked on in the second + third. We wiped a*s on Foxey Lady.”

The May 1st entry finds an interesting partial lyric composition: “Wednesday, such a mellow day. Blowing wind + the children play!! I see the glowing sun shining down, I feel the pain and I wear a frown. It can’t be a dream, It’s not what it seems. But I am dying now.” In the Spring of 1968, the band was carving out its own identity, trying hard not to be just another cover band, by writing and practicing original compositions. Their set list now included seven new songs: “Rize Up”, “Charlotte”, “Fool of Cotton”, “Dance the form Evil”, “Turn on Green”, “Impression in F”, and their newest song, “Good Things for our Minds”. May 4th’s entry announced that the Morticians would be playing a gig at the Hullabaloo Club in Muncie alongside the British pop group, The Cryin’ Shames, who had a minor hit with the remake of the 1961 song “Please Stay” by The Drifters. The Drifters’ claim to fame (and ultimate demise) came when they turned down a managerial offer from Brian Epstein, manager of The Beatles. The April 15th entry describes, “We play the first set + they play the second, we play the third + they play fourth. We’re supposed to use our equipment and they theirs. We will definitely have to completely wipe them out. We will increase their draw by 200 people. There’ll be a lot of people discussing recording records etc. It should prove to be a very exciting evening.”

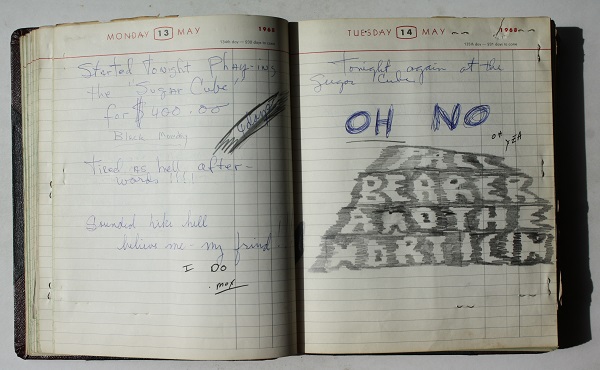

May 13 entry: “Started tonight playing the Sugar Cube for $100 [per night]. Tired as hell afterwards!” The Sugar Cube nightclub was located close to Marhofers Meat Packing Co. on Granville Avenue in Muncie. The Morticians gigged at the Sugar Cube from May 13th to the 18th for a whopping $400 paycheck! Paul Bearer and the Morticians played the “In Club” in Van Wert, Ohio for $125. May 25th: “Jack quit the band. We have to look for a new drummer-probably get Roy Buckner.” May 31, the band played a show at the Youth Center in Syracuse, IN. for $125 payday. “There were a lot of teeny boppers there that dug us bad. We will definitely go back later this summer.” By June, the band was adding more original songs to their setlist: “Manic Depression”, “Little Miss (Over)”, “Come on in”, “Talk Talk”, “You Don’t Know Like I Know”, and “When I Was Young”. June 15: “McPherson’s probably for $150…The clown only went $130.” June 21, the boys played the YMCA in Peru, In. for $150. During a dry spell for the band, one entry reads: “Went to the fabulous Anderson Fair (cow dung everywhere) + then bopped over to Phillips Swimming Hole in Muncie-It was real coooool man.” Muncie’s Phillips public swimming pool opened in 1922 and was closed in 1961 and thereafter used for training by the Muncie fire department.

July 5th, 1968, finds the band playing “The Hub” in Celina, Ohio, for $125. “We didn’t get a good reaction at first, but the third set was real good. Wiped up with Purple Haze, Fire, Foxey Lady, + You Know. I would go to Russia, Vietnam, Belgium, France, The Congo, Brazil, but NOT THE HUB.” A month later (August 3rd), a diary entry reads: “There was an atomic attack on Celina, Ohio today. Luckily, no one was saved. Praise Allah.” July 6: “Found out The Who are back in the United States for a 9-week tour. They’ll def. pass thru here. The Fab Beach Boys are in town along with the Union Gap + The Human Beings.” July 11, the band is playing at the Honeywell Pool in Wabash, In, for $150. Two days later, they are playing in Shelbyville for $150. “We def. will not play for less than $150 beans from now on. $25 raise when we cut the record. They bought us on our gimmick-Dry Ice- fog during our performance.” Despite that entry, days later, on June 21st, the band was once again appearing at the Hullabaloo in Muncie for a $130 payday. In the end, the band netted $57 and paid out $15 per band member. August 8: “Rick quit the band, supposedly, then came crawling back 3 days later, acting like it was all a gag! HAR.”

August 9th, 1968, finds the band playing at Jefferson Landing, 127 E. Main St. in Crawfordsville for $150.”It was a real sweet place, but NOBODY showed up-cause it’s Tuesday, no doubt. We got a real good report from here though.” Five days later, the Morticians were once again playing The Place in Fortville for $150. “We finally are going back to play at Fortville once more. It will really bring back old memories. Har de Har de Har!!! All they could say was that it was too loud.” On August 25, Paul Bearer and the Morticians played the Indiana State Fair [likely a warmup for The Cowsills]: “They were really digging our music.” Sept. 3rd finds the band playing a dance at the Bridge Vu Theatre in Valparaiso, IN,. for $175. October 4, 1968: “Today is the 2nd anniversary of PB + M. Ain’t you proud? I found a super contact: Jeff Beck. He is supposed to speak at the Gent tomorrow.” Oct. 12th finds the band playing a Halloween party at the Kendallville Youth Center in Kendallville, IN., for $175. “Everything was going great, until old nag (blind) started raising the roof because she thought we were a bunch of maniacs, how right she was! The kids dug us so much, they clapped after every song.” The show went over so well, the band was asked to play again the next night. On Oct. 25th, the band played the Sigma Phi Epsilon frat house at Ball State in Muncie for $100. Immediately following the show, the band drove straight to New York to see Steppenwolf. On Nov. 6, the band was playing a show at “The Anchor” in Findlay, Ohio, for $125. Nov. 8, 1968: “Went to Indianapolis + saw Canned Heat + Iron Butterfly-Boy were they great. Worth every minute, they were.”

Nov. 11, the band booked a $150 gig at the Purity Inn on High Street in Oxford, Ohio. “They said we were too loud. We won’t go back def. The acoustics were totalled. We each got 20 beans apiece tonight.” Nov. 20, the band played the armory in Crawfordsville, IN., for $175. “We turned WAY DOWN but don’t know if they liked us or not. We split the diff. + each for 30 Beans.” Nov. 30 the band was once again playing the Hullabaloo in Muncie for $135. Dec. 2nd, the band played the Sigma Pi House at Purdue University for $125. “They seemed to like us quite well + I think we did one of our better gigs. They really dug it bad.” The gigs were getting fewer and farther between now and the diary entries ceased until December 29, 1968. “Played at the Muncie Haullabaloo Club today for a measly $43.57, which was 50% of the door-WOW! We’ll probably be playing there steady at jam sessions on Sundays-NO CONTRACT yet.”

Two days later, on New Year’s Eve, 1968, the diary reads: “The last day of ’68-finally. We are being completely taken over by Son Productions. This is the last day, as we know it of Paul Bearer + the Morticians. Fare thee well, my fellow compatriots.” The annual tally for 1968 totalled $5,518.07, or just over $50,000 in today’s money. The memoranda section of the diary reads: “Cut our first record in August!!-FARCE. We Are Mushroom People. We Are Dead.”

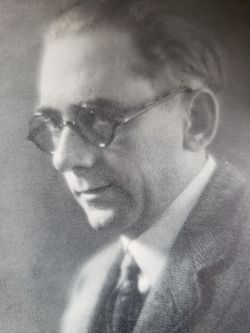

As hard as it is to find detailed information on Paul Bearer and the Morticians, it is even harder to find info on Son Records. Initial information can be found on the band’s contracts, where Larry Scherer signs as the legal representative of “Son Productions P.O. Box 78 Yorktown, Ind. 47396 (Phone) 759-9371”. One article found in the August 1, 1968, Muncie Star newspaper, notes that Son Records founder, Roger Warrum, was born in Shelbyville, attended Mount Comfort schools, graduated from Ball State University, lived in Greenfield, and settled in Anderson. Warrum had a band, The Glass Museum, and also brokered the Jimi Hendrix Concert in Muncie at the Hullabaloo Club. He formed “Son Productions” (named to honor his son Jeffrey Scott) in late 1966 and was described as the “founder-manager-chief worker” for the licensed music booking agency. The company logo incorporated sun rays jutting out of the “o” in “Son”. Warrum made his office inside the Muncie Hullabaloo building, booking bands in Indiana, Eastern Michigan, Ohio, and Kentucky. He opened a branch in Valparaiso to serve the Chicagoland & Greater Michigan, Illinois, and Wisconsin regions. The article states that Warrum planned to open more branches in Bloomington (in October) and Michigan (in January). Warrum only booked union bands and notes, “Paul Bearer and the Morticians came back [to the Muncie Hullabaloo] three times before they had a big enough, good enough sound to make the circuit.” Roger J. Warrum would go on to a successful Insurance career in Anderson, where he was elected to the City Council. He died in Hudson, Ohio in 2009 at the age of 63.

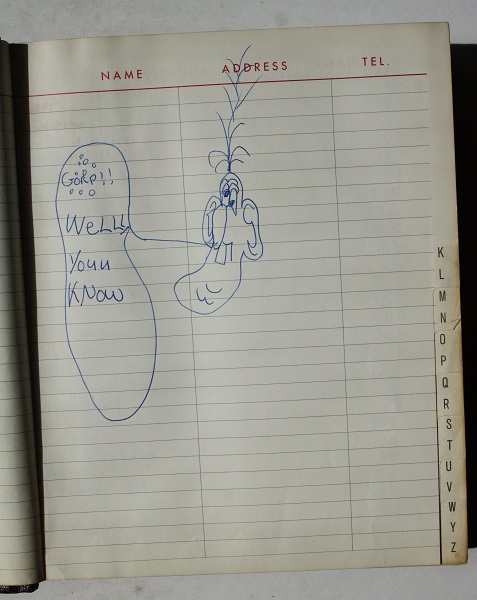

As detailed in Part I of this series, the diarist of these books, Larry Scherer (Paul Bearer himself), died at his home in Greenfield on Jan. 23, 2004, following a brief illness. After the band broke up, Larry taught school in Broxton, GA, and was Teacher of the Year three times. He relocated to Anderson in 1978 and was employed by Madison County Employment & Training Administration as an Assessment Testing Counselor and the Director of Weatherization. Larry was the owner/operator of his business as a General Construction Contractor. As for the rest of the band, Vic Burnett was the guitarist, organist, vocalist, and songwriter, and Jim Shannon was the bassist for the band. Jim Shannon’s signature appears in the diary with a comic profane inscription. Other names appearing on the pages of the diary include Tim Connelly, Jack McCleese, Phil Daily, Rick Thompson, Mike Ford, Chris Wisehart, Michael Eddie, Dave Robertson, Charlie Phillips, Dick Maddox, Steve Whitesell, Ed Wyatt (from Florida), Mike Moore, and Gary Rinker. It should be assumed that these men were members of, or closely associated with, the band.

Despite their hopes of becoming a headliner band, Paul Bearer and the Morticians were little more than a hobby, which they all hoped would turn into something bigger but never did. A thread on the net can be found from Chris Shannon (relative of bassist Jim Shannon) stating that “Paul Bearer and the Morticians made an appearance via satellite on either the Jerry Lewis Telethon or Dick Clark’s American Bandstand. Any time they played in public, the street would be packed with people listening to them play. They were hot, man!” I have spent the last month trying to connect with any family members of the men who created this band, including Chris Shannon, to no avail. So, Chris, if you’re out there, I’d love to hear from you and learn more about Paul Bearer and the Morticians. So, there you have it, the little-known story of a typical 1960s Indiana garage band.