Original publish date: November 13, 2014

Republished: November 22, 2018

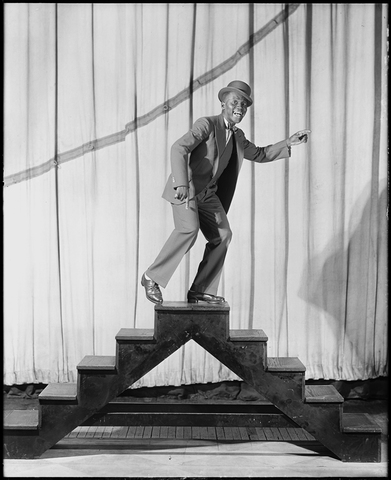

Bill “Bojangles” Robinson was the most famous of all African American tap dancers of the twentieth century. No wait, he was, race notwithstanding, the most famous tap-dancer of all time. Robinson used his popularity to challenge and overcome numerous racial barriers, becoming one of the first minstrel and vaudeville performers to appear without the use of blackface makeup (Yes, African American performers were required to perform in Blackface up until World War I). One of the earliest African American performers to go solo.The first African American to appear in a Hollywood film in an interracial dance team (with Temple in The Little Colonel) and the first African American to headline a mixed-race Broadway production.

Offstage Robinson was the first Hollywood Civil Rights activist by using his fame to persuade the Dallas police department to hire its first African American policemen. He staged the first integrated public event in Miami, a fundraiser which, with the permission of the mayor, was attended by both black and white city residents. He also used his star power to lobby President Franklin D. Roosevelt for more equitable treatment of African American soldiers during World War II. Orphaned at a young age and raised by a grandmother who was a former slave, Bill Robinson was born to make a difference.

In the early 1920s, Robinson took his career on the road as a solo vaudeville act, touring throughout the country. He frequently visited Indianapolis, where he performed multiple shows per night, often on two different stages, at the B.F.Keith theatre. Robinson worked 51 weeks per year, taking a week off every season for the World Series. Bojangles was an avid baseball fan and co-founder of the New York Black Yankees of the old Negro National League in 1936.

In the early 1920s, Robinson took his career on the road as a solo vaudeville act, touring throughout the country. He frequently visited Indianapolis, where he performed multiple shows per night, often on two different stages, at the B.F.Keith theatre. Robinson worked 51 weeks per year, taking a week off every season for the World Series. Bojangles was an avid baseball fan and co-founder of the New York Black Yankees of the old Negro National League in 1936.

Toward the end of the vaudeville era, Robinson joined other black performers on Broadway in “Blackbirds of 1928”, an all- black revue for white audiences. After 1930, black revues waned in popularity, but Robinson remained popular with white audiences for more than a decade starring in fourteen motion pictures produced by such companies as RKO, 20th Century Fox, and Paramount Pictures. Most of them had musical settings, in which he played old-fashioned roles in nostalgic romances. Robinson appeared opposite Will Rogers in In Old Kentucky (1935), the last movie Rogers made prior to his death in an airplane crash. Robinson and Rogers were good friends, and after Rogers’ death, Robinson refused to fly, instead travelling by train to Hollywood for his film work.

He was cast as a specialty performer in a standalone scene. This practice, customary at the time, permitted Southern theaters to remove scenes containing black performers from their showings of the film. Times being what they were, his most frequent role was that of an antebellum butler or servant opposite reigning #1 box office moppet Shirley Temple in films: The Little Colonel (1935), The Littlest Rebel (1935), Just Around the Corner (1938) and Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (1938). In addition, he assisted in the choreography on one of her other films, Dimples (1936). Robinson and Temple became the first interracial dance partners in Hollywood history and lifelong friends. The dance scenes, controversial for their time, were cut out in the south along with all other scenes showing Temple and Robinson making physical contact. By 1937 Robinson was earning $6,600 a week for his films, a strikingly high sum for a black entertainer in Hollywood at the time.

At the 1939 New York World’s Fair, he returned to the stage in “The Hot Mikado”, a jazz version of the Gilbert and Sullivan operetta which quickly became one of the greatest hits of the fair. Consequently, August 25, 1939 was named ‘’Bill Robinson Day’’ at the World’s Fair. By the 1940s, although he continued to perform, Robinson was past his prime and showing symptoms of heart disease. Robinson’s final film appearance is considered by critics as his best when he starred in the 1943 Fox musical Stormy Weather alongside Lena Horne.

At the 1939 New York World’s Fair, he returned to the stage in “The Hot Mikado”, a jazz version of the Gilbert and Sullivan operetta which quickly became one of the greatest hits of the fair. Consequently, August 25, 1939 was named ‘’Bill Robinson Day’’ at the World’s Fair. By the 1940s, although he continued to perform, Robinson was past his prime and showing symptoms of heart disease. Robinson’s final film appearance is considered by critics as his best when he starred in the 1943 Fox musical Stormy Weather alongside Lena Horne.

From 1936 until his death in 1949, Robinson made numerous radio and occasional television appearances. It was during these appearances that Robinson introduced and popularized a word of his own invention, copacetic, meaning tip-top, which he had used for years in his vaudeville shows. It was added to Webster’s Dictionary dictionary in 1934. During the 1930-40s, Robinson was appointed as the honorary Mayor of Harlem, a lifetime member of countless policemen’s associations and fraternal orders, and a mascot of the New York Giants major league baseball team.

Onstage, Robinson’s open face, twinkling eyes and infectious smile were irresistible and his tapping was delicate and clear. Robinson had no doubts that he was the best at what he did, a self-confidence that some mistook for arrogance. Bojangles felt that he had more than paid his dues and sometimes brooded that, because he was black, he had to wait until he was in sixties before he could enjoy the fame and fortune given to less talented white dancers. Rivals and wags pointed to Robinson’s lack of education as the reason for his nasty demeanor and pegged Bill as confrontational, quarrelsome, and as a heavy drinker and gambler. But they could not deny that his dancing was extraordinary.

On March 21, 1908, as a result of a dispute with a tailor over a suit, Robinson was arrested in New York City for armed robbery. After being released on bail, Robinson failed to take the charges and impending trial seriously. He paid little attention to mounting a defense. On September 30, Bojangles was shocked when he was convicted and sentenced to 11–15 years hard labor in New York’s Sing Sing prison. Robinson’s influential friends hired a new attorney who produced evidence that Robinson had been falsely accused. Though he was exonerated at his second trial and his accusers indicted for perjury, the trial and time spent in the Tombs (Manhattan’s prison complex) affected Robinson deeply. After he was released, he never again traveled unarmed and made a point of registering his pistol at the local police station of each town where he performed. Robinson’s wife, Fanny, always sent a letter of introduction with complimentary tickets and other gifts to the local police chief’s wife in each town ahead of her husband’s engagements.

Robinson loved to play pool and insisted on silence when he attempted certain shots. At these times when the game was on the line, he would pull out his pistol, lay it on the edge of the pool table and take his shot, as the stunned patrons fell silent. African-American newspapers often derided Robinson as the quintessential Uncle Tom because of his cheerful and shameless subservience to whites on film. But in real life Robinson was the sort of man who, when refused service at all-white restaurants, would lay his gold-plated pearl-handled revolver on the counter and demand to be served.

Despite these adverse incidents that appear to reveal more about the times than the man, in fact, Robinson was a remarkably generous man. His participation in benefits is legendary and it is estimated that he gave away well over one million dollars in loans and charities during his lifetime. Despite his massive workload, he never refused to appear at a benefit for those artists who were less successful or ailing. It has been estimated that in one year he appeared in a staggering 400 benefits. Often on two different stages in the same city on the same night. Despite earning and spending a fortune, his memories of surviving the streets as a child never left him, prompting many acts of generosity.

Bill “Bojangles” Robinson held the world record for running backward. He learned this skill while a young vaudevillian and used the trick to generate publicity in cities where he wasn’t the headliner. He called them “freak sprinting” races and would challenge all comers, including Olympic Champion Jesse Owens. He never lost in his lifetime. Later, the duo became such good friends that Owens made a gift to Robinson of one of his four Olympic gold medals. In 1922, Robinson set the world record for running backward (100 yards in 13.5 seconds). The record stood until 1977, when it was beaten by two-tenths of a second.

After a series of heart attacks, doctors advised him to quit performing in 1948. Robinson maintained that though he had trouble walking, talking, sleeping and breathing, when he danced he felt wonderful. Robinson’s final public appearance was as a surprise guest on Ted Mack’s Original Amateur Hour TV show. He died a few weeks later on November 25, 1949. Despite earning more than $ 3 million during his lifetime, Robinson died penniless at the age of 71 from heart failure at Columbia Presbyterian Center in New York City . His funeral was arranged and paid for by longtime friend and television host Ed Sullivan.

Robinson’s casket lay in state in Harlem, where an estimated 32,000 people filed past to pay their last respects. The schools in Harlem were closed for a half-day so that children could attend or listen to the funeral, which was broadcast over the radio. Reverend Adam Clayton Powell, Sr. conducted the service at the Abyssinian Baptist Church, and New York Mayor William O’Dwyer gave the eulogy. Newspapers estimated that one hundred thousand people turned out to witness the passing of his funeral procession. Robinson is buried in the Cemetery of the Evergreens in Brooklyn. In 1989, a joint U.S. Senate/House resolution declared “National Tap Dance Day” to be May 25, the anniversary of Bill Robinson’s birth.

Robinson’s casket lay in state in Harlem, where an estimated 32,000 people filed past to pay their last respects. The schools in Harlem were closed for a half-day so that children could attend or listen to the funeral, which was broadcast over the radio. Reverend Adam Clayton Powell, Sr. conducted the service at the Abyssinian Baptist Church, and New York Mayor William O’Dwyer gave the eulogy. Newspapers estimated that one hundred thousand people turned out to witness the passing of his funeral procession. Robinson is buried in the Cemetery of the Evergreens in Brooklyn. In 1989, a joint U.S. Senate/House resolution declared “National Tap Dance Day” to be May 25, the anniversary of Bill Robinson’s birth.

Bill Robinson was successful despite the obstacle of racism. My favorite Robinson story finds Bojangles seated in a restaurant as a rude customer loudly object to his presence. When the manager suggested that it might be better if Robinson left, Bill smiled and asked, “Have you got a ten dollar bill?” As the manager lays his bill on the counter, Robinson removes six $10 bills from his own wallet and adds them to the manager’s banknote. After mixing all of the bills together, Robinson says, “Here, let’s see you pick out the colored one”. The restaurant manager served Robinson without further delay.

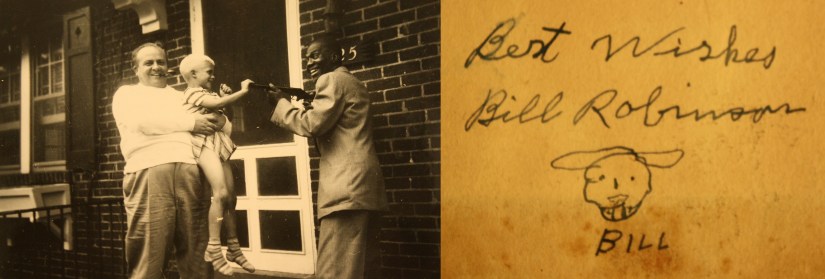

So there you have it, a 2-part story of a true American hero. Now you know why I was so happy to find that suitcase of Big Band memorabilia containing items associated with Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. I’ve already told you about most of the contents in that suitcase. But there is one item that shines above all others. Well, to me at least.

It is a page out of an old fashioned scrapbook. On that page is a small photo of Deke Moffitt with his friend Bojangles. Moffitt is holding his son up and the trio are clowning with a toy pop-gun. The typewritten caption under the photo reads: “I think this was the last snap-shot ever taken of Bill Robinson. It was taken on July 13, 1949.” Of course, there is no real way to prove that claim, but it is certainly intriguing. Under the photo, also attached to the page is a small hand drawn self caricature titled “Bill” with an autograph above it reading “Best Wishes Bill Robinson”. The sketch was drawn by Bill “Bojangles” Robinson himself and it speaks to the innocence and purity of the image Mr. Robinson projected on screen all those years ago.

If you’re old enough to remember Black and White TV, the original Sammy Terry TV show, Timothy Church-mouse or Cowboy Bob and Janie, then you should remember Bill Robinson. If you’re over the age of 40, you can remember a time before cable TV. A time when television stations actually went off the air at night and didn’t come back on until farm shows or cartoons popped up the next morning. Back then, it was a badge of honor to say you made it up to watch the flag wave to the rhythm of the National Anthem.

If you’re old enough to remember Black and White TV, the original Sammy Terry TV show, Timothy Church-mouse or Cowboy Bob and Janie, then you should remember Bill Robinson. If you’re over the age of 40, you can remember a time before cable TV. A time when television stations actually went off the air at night and didn’t come back on until farm shows or cartoons popped up the next morning. Back then, it was a badge of honor to say you made it up to watch the flag wave to the rhythm of the National Anthem. For the sake of full disclosure, I must admit that I once owned a photo signed by Bill Robinson. Bojangles signed it for an Indiana Mayor whose name now escapes me. I sold it to a collector in the late 1980s for $ 100. But I rationalized the sale of the relic because the photo literally looked like it had been dipped in water and $ 100 might as well have been $ 1,000 to me and my young bride. By finding this photo on a dew soaked Southern Indian hillside, I felt the pendulum had swung back my way.

For the sake of full disclosure, I must admit that I once owned a photo signed by Bill Robinson. Bojangles signed it for an Indiana Mayor whose name now escapes me. I sold it to a collector in the late 1980s for $ 100. But I rationalized the sale of the relic because the photo literally looked like it had been dipped in water and $ 100 might as well have been $ 1,000 to me and my young bride. By finding this photo on a dew soaked Southern Indian hillside, I felt the pendulum had swung back my way.

Friends say there were three certainties about Bill Robinson: he loved to eat vanilla ice cream, gamble with dice or cards, and dancing was his life. At the time of his divorce his wife Fannie accused him of being a danceaholic-a man willing to sacrifice everything to dance. While his personal life was full of contradictions, his peers and historians agree he was one of the greatest American dancers of all time.

Friends say there were three certainties about Bill Robinson: he loved to eat vanilla ice cream, gamble with dice or cards, and dancing was his life. At the time of his divorce his wife Fannie accused him of being a danceaholic-a man willing to sacrifice everything to dance. While his personal life was full of contradictions, his peers and historians agree he was one of the greatest American dancers of all time. Following the demise of vaudeville, Broadway beckoned with “Blackbirds of 1928,” an all-black revue that would prominently feature Bill and other black musical talents. Soon, he was headlining with Cab Calloway at the famous Cotton Club in Harlem. Robinson is also credited with having introduced a new word, copacetic, into popular culture, via his repeated use of it in vaudeville and radio appearances. Robinson was a true pioneer in his field with many “firsts” to his credit.

Following the demise of vaudeville, Broadway beckoned with “Blackbirds of 1928,” an all-black revue that would prominently feature Bill and other black musical talents. Soon, he was headlining with Cab Calloway at the famous Cotton Club in Harlem. Robinson is also credited with having introduced a new word, copacetic, into popular culture, via his repeated use of it in vaudeville and radio appearances. Robinson was a true pioneer in his field with many “firsts” to his credit.

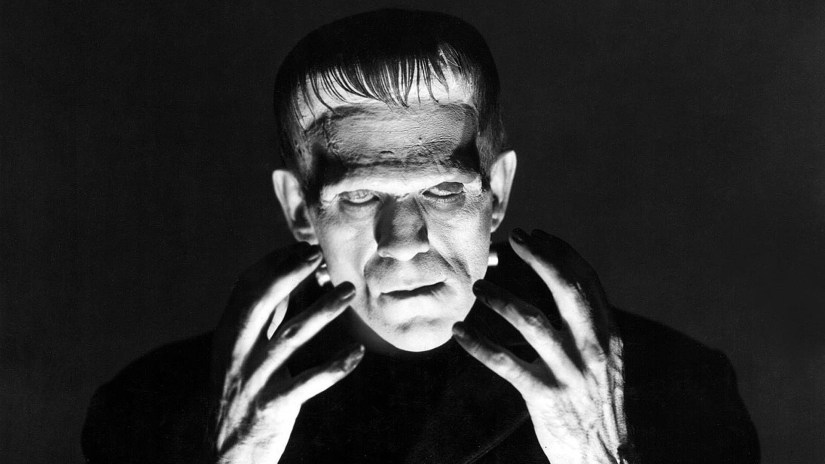

What better time to introduce two of the world’s most popular monsters? Frankenstein and Dracula were born on the same night in the same weekend in 1816. They were brought to life by Mary Shelley and Lord Byron during a contest to see who could create the scariest monster. The weekend was wet and stormy and Lord Byron suggested the reading of ghost stories to pass away the dreary weather. Sitting around a log fire at the Villa Diodati on the shores of Lake Geneva, the company of friends amused themselves by reading German ghost stories translated into French from the book Fantasmagoriana. The members of the party were Lord Byron and his mistress Claire Claremont, his doctor John Polidori, Percy Bysshe and Mary Shelley. Lord Byron is known for his poetry, mostly Don Juan. After reading a few stories, Byron suggested that each member of their party write their own story of horror.

What better time to introduce two of the world’s most popular monsters? Frankenstein and Dracula were born on the same night in the same weekend in 1816. They were brought to life by Mary Shelley and Lord Byron during a contest to see who could create the scariest monster. The weekend was wet and stormy and Lord Byron suggested the reading of ghost stories to pass away the dreary weather. Sitting around a log fire at the Villa Diodati on the shores of Lake Geneva, the company of friends amused themselves by reading German ghost stories translated into French from the book Fantasmagoriana. The members of the party were Lord Byron and his mistress Claire Claremont, his doctor John Polidori, Percy Bysshe and Mary Shelley. Lord Byron is known for his poetry, mostly Don Juan. After reading a few stories, Byron suggested that each member of their party write their own story of horror. Unable to think of a story, young Mary became anxious, in the introduction to her book she recalled: “Have you thought of a story? I was asked each morning, and each morning I was forced to reply with a mortifying negative.” During one evening in the middle of summer, the discussions turned to the nature of the principle of life. “Perhaps a corpse would be re-animated”, Mary noted, “galvanism had given token of such things”. It was after midnight before they retired, and unable to sleep, she became possessed by her imagination as she beheld the grim terrors of her “waking dream.” In September 2011, astronomer Donald Olson, after visiting the Lake Geneva villa and inspecting data about the motion of the moon and stars, concluded that her “waking dream” took place “between 2 a.m. and 3 a.m.” on June 16, 1816, several days after the initial idea by Lord Byron that they each write a ghost story.

Unable to think of a story, young Mary became anxious, in the introduction to her book she recalled: “Have you thought of a story? I was asked each morning, and each morning I was forced to reply with a mortifying negative.” During one evening in the middle of summer, the discussions turned to the nature of the principle of life. “Perhaps a corpse would be re-animated”, Mary noted, “galvanism had given token of such things”. It was after midnight before they retired, and unable to sleep, she became possessed by her imagination as she beheld the grim terrors of her “waking dream.” In September 2011, astronomer Donald Olson, after visiting the Lake Geneva villa and inspecting data about the motion of the moon and stars, concluded that her “waking dream” took place “between 2 a.m. and 3 a.m.” on June 16, 1816, several days after the initial idea by Lord Byron that they each write a ghost story. When “Frankenstein” was published it became an immediate sensation. Mary Shelley crafted her book so that readers’ sympathies would lie not only with Frankenstein, whose suffering is dreadful, but also with the creature, whose suffering is worse. Shelley skillfully directs her readers’ sympathy, page by page, paragraph by paragraph, sometimes even line by line, from Frankenstein to the creature. Shelley deftly navigates the creature’s vicious murders, first of Frankenstein’s little brother, then of his best friend, and, finally, of his bride. In 1824, one critic wrote, “The justice is indisputably on his side and his sufferings are, to me, touching to the last degree.”

When “Frankenstein” was published it became an immediate sensation. Mary Shelley crafted her book so that readers’ sympathies would lie not only with Frankenstein, whose suffering is dreadful, but also with the creature, whose suffering is worse. Shelley skillfully directs her readers’ sympathy, page by page, paragraph by paragraph, sometimes even line by line, from Frankenstein to the creature. Shelley deftly navigates the creature’s vicious murders, first of Frankenstein’s little brother, then of his best friend, and, finally, of his bride. In 1824, one critic wrote, “The justice is indisputably on his side and his sufferings are, to me, touching to the last degree.” A century later, a lurching, grunting Boris Karloff defined the most widely accepted version of the creature in Universal Pictures’s 1931 production of “Frankenstein.” Karloff’s monster-portrayed as prodigiously eloquent, learned, and persuasive in the novel-was no longer merely nameless but all but speechless, too. “Frankenstein” has spawned many different depictions in the two centuries since its publication. For its bicentennial, the original, 1818 edition has been reissued in paperback form by Penguin Classics as “The New Annotated Frankenstein.”

A century later, a lurching, grunting Boris Karloff defined the most widely accepted version of the creature in Universal Pictures’s 1931 production of “Frankenstein.” Karloff’s monster-portrayed as prodigiously eloquent, learned, and persuasive in the novel-was no longer merely nameless but all but speechless, too. “Frankenstein” has spawned many different depictions in the two centuries since its publication. For its bicentennial, the original, 1818 edition has been reissued in paperback form by Penguin Classics as “The New Annotated Frankenstein.”

The Chicago club opened on a bitterly cold day in Chicago, yet lines of eager prospective members stretched around the block, warmed by ideas of what was to be found inside. Membership was available to anyone willing to purchase a key – $50 for residents and $25 for out-of-towners. The club “key” itself was metal and topped off with a rabbit head, later replaced by a gold plastic credit card to carry in a wallet. Hefner was present at the grand opening until the club closed at 4am. Keyholders gawked at ladies in their colorful Playboy Bunny outfits and dined on steaks and salads (no fancy hors d’oeuvres or desserts here), drank cocktails and bought packs of cigarettes and Playboy logo lighters. Most club items were available for the standard price of $1.50 per item (an exorbitant price at the time, especially for drinks and cigarettes). In the club’s first year, entertainment included the most popular stars of the day, including Mel Torme, Barbara Streisand and a 19-year-old Aretha Franklin.

The Chicago club opened on a bitterly cold day in Chicago, yet lines of eager prospective members stretched around the block, warmed by ideas of what was to be found inside. Membership was available to anyone willing to purchase a key – $50 for residents and $25 for out-of-towners. The club “key” itself was metal and topped off with a rabbit head, later replaced by a gold plastic credit card to carry in a wallet. Hefner was present at the grand opening until the club closed at 4am. Keyholders gawked at ladies in their colorful Playboy Bunny outfits and dined on steaks and salads (no fancy hors d’oeuvres or desserts here), drank cocktails and bought packs of cigarettes and Playboy logo lighters. Most club items were available for the standard price of $1.50 per item (an exorbitant price at the time, especially for drinks and cigarettes). In the club’s first year, entertainment included the most popular stars of the day, including Mel Torme, Barbara Streisand and a 19-year-old Aretha Franklin. The Bunnies themselves were instructed, in a 44-page “Bunny Manual”, that they could not date customers, give out their phone numbers, or meet their boyfriends or husbands within two blocks of the club. If they did, they would face the tortuous penalty of being banned from the “bunny hutch.” There were different types of Bunnies, including the Door Bunny, Cigarette Bunny, Floor Bunny, Playmate Bunny and the Jet Bunnies (specially selected to serve on the Playboy “Big Bunny” Jet). To become a Bunny, women first had to audition. Prospective “Kits” (short for “Kitten Rabbits”) underwent thorough and strict training before officially becoming a Bunny. Bunnies were required to be able to identify 143 brands of liquor and know how to garnish 20 cocktail variations. Customers were also not allowed to touch the Bunnies, and demerits were given if a Bunny’s appearance was not properly organized.

The Bunnies themselves were instructed, in a 44-page “Bunny Manual”, that they could not date customers, give out their phone numbers, or meet their boyfriends or husbands within two blocks of the club. If they did, they would face the tortuous penalty of being banned from the “bunny hutch.” There were different types of Bunnies, including the Door Bunny, Cigarette Bunny, Floor Bunny, Playmate Bunny and the Jet Bunnies (specially selected to serve on the Playboy “Big Bunny” Jet). To become a Bunny, women first had to audition. Prospective “Kits” (short for “Kitten Rabbits”) underwent thorough and strict training before officially becoming a Bunny. Bunnies were required to be able to identify 143 brands of liquor and know how to garnish 20 cocktail variations. Customers were also not allowed to touch the Bunnies, and demerits were given if a Bunny’s appearance was not properly organized.

Most readers are aware of feminist Gloria Steinem’s crusade to expose the sexist treatment of Playboy Bunnies in her 1983 book “Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions.” The article featured a photo of Steinem in Bunny uniform and detailed how women were treated at those clubs. The article was first published in 1963 in Show magazine as “A Bunny’s Tale”. But are there any other famous former Bunnies out there? Well, yes, the “hutch” is littered with the names of young, struggling Hollywood actresses. Some are familiar: Lauren Hutton, Sherilyn Fenn (Twin Peaks TV star), Barbara Bosson (Hill Street Blues TV star), Patricia Quinn (Magenta from Rocky Horror), Kathryn Leigh Scott (Dark Shadows TV star) and many others. Jon Bon Jovi’s mom, Carol Sharkey, was a Bunny as was Kimba Wood, Bill Clinton’s nominee for Attorney General in 1993. At least 32 former Bunnies were also Playboy Magazine Centerfold “Playmates.” Rock stars Dale Bozzio (Missing Persons and Frank Zappa) and Blondie’s Debbie Harry were also Bunnies. Harry once famously remarked, “The girls there were part of the entertainment; part of the sort of mystique, the excitement, the naughtiness of it. But on the inside of that job, the girls were treated very, very well. There was a lot of benefits: health benefits, job security, good salary, good money. It was a very sought-after kind of job.”

Most readers are aware of feminist Gloria Steinem’s crusade to expose the sexist treatment of Playboy Bunnies in her 1983 book “Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions.” The article featured a photo of Steinem in Bunny uniform and detailed how women were treated at those clubs. The article was first published in 1963 in Show magazine as “A Bunny’s Tale”. But are there any other famous former Bunnies out there? Well, yes, the “hutch” is littered with the names of young, struggling Hollywood actresses. Some are familiar: Lauren Hutton, Sherilyn Fenn (Twin Peaks TV star), Barbara Bosson (Hill Street Blues TV star), Patricia Quinn (Magenta from Rocky Horror), Kathryn Leigh Scott (Dark Shadows TV star) and many others. Jon Bon Jovi’s mom, Carol Sharkey, was a Bunny as was Kimba Wood, Bill Clinton’s nominee for Attorney General in 1993. At least 32 former Bunnies were also Playboy Magazine Centerfold “Playmates.” Rock stars Dale Bozzio (Missing Persons and Frank Zappa) and Blondie’s Debbie Harry were also Bunnies. Harry once famously remarked, “The girls there were part of the entertainment; part of the sort of mystique, the excitement, the naughtiness of it. But on the inside of that job, the girls were treated very, very well. There was a lot of benefits: health benefits, job security, good salary, good money. It was a very sought-after kind of job.” The Chicago Playboy Club enjoyed a long and successful quarter century run, but closed in 1986. Today, the “One Magnificent Mile Building” has replaced the Chicago Playboy Club, and in 2000, that stretch of Walton was given the honorary name of “Hugh Hefner Way.” The original magazine headquarters was located nearby as was the original Playboy Mansion at 1340 N. State St., both of which have also moved on. Sadly, nothing has quite replaced the Playboy Club in Chicago. Hugh Hefner died at his home in Holmby Hills, Los Angeles, California, on September 27, 2017, at the age of 91. The cause was sepsis brought on by an E. coli infection. He is interred at Westwood Memorial Park in Los Angeles, in the $75,000 crypt beside Marilyn Monroe. “Spending eternity next to Marilyn is an opportunity too sweet to pass up.”

The Chicago Playboy Club enjoyed a long and successful quarter century run, but closed in 1986. Today, the “One Magnificent Mile Building” has replaced the Chicago Playboy Club, and in 2000, that stretch of Walton was given the honorary name of “Hugh Hefner Way.” The original magazine headquarters was located nearby as was the original Playboy Mansion at 1340 N. State St., both of which have also moved on. Sadly, nothing has quite replaced the Playboy Club in Chicago. Hugh Hefner died at his home in Holmby Hills, Los Angeles, California, on September 27, 2017, at the age of 91. The cause was sepsis brought on by an E. coli infection. He is interred at Westwood Memorial Park in Los Angeles, in the $75,000 crypt beside Marilyn Monroe. “Spending eternity next to Marilyn is an opportunity too sweet to pass up.”

With the choice of O’Neill’s work, “The Emperor Jones”, the Society was taking an enormous risk if only for the fact that it required an elaborate stage for a one night performance. And then there was the Klan. The KKK was growing by leaps and bounds despite the fact that it had just been formally recognized in the state that same year. Soon, one third of the native male white born citizenry of the state would belong to the Klan. This was a play solely centered around a strong, murderous black man in a position of absolute authority in production in the principally white governed center of the WASP-ish Midwestern cornbelt.

With the choice of O’Neill’s work, “The Emperor Jones”, the Society was taking an enormous risk if only for the fact that it required an elaborate stage for a one night performance. And then there was the Klan. The KKK was growing by leaps and bounds despite the fact that it had just been formally recognized in the state that same year. Soon, one third of the native male white born citizenry of the state would belong to the Klan. This was a play solely centered around a strong, murderous black man in a position of absolute authority in production in the principally white governed center of the WASP-ish Midwestern cornbelt. W. F. McDermott, drama editor of the Indianapolis News, wrote this about Long: “a colored actor, played the role of the emperor with several moments of great naturalness. He was able to portray the negro fear of “ha’nts” with unusual power.” But McDermott was less kind to the playwrite, “O’Neill writes darkly of brooding, inscrutable fate; of black and stormbound heights, of man, stripped savage and terrified; of man tragically at odds with his environment and foredoomed.”

W. F. McDermott, drama editor of the Indianapolis News, wrote this about Long: “a colored actor, played the role of the emperor with several moments of great naturalness. He was able to portray the negro fear of “ha’nts” with unusual power.” But McDermott was less kind to the playwrite, “O’Neill writes darkly of brooding, inscrutable fate; of black and stormbound heights, of man, stripped savage and terrified; of man tragically at odds with his environment and foredoomed.” Perhaps the most unusual feature of the Indianapolis production was the choice of the lead actor chosen to portray Brutus Jones. Arthur Theodore Long was born on December 31, 1884, the son of Henry and Nattie (Buckner) Long in Morrillton, Arkansas. According to the 6th edition of “Who’s Who in Colored America (1941-1944)”, Long graduated from Sumner High School in St. Louis, Missouri in 1904. He entered the University of Illinois at age twenty and earned a BA degree in 1908. Arthur then went on to further his education at both Indiana and Butler universities. He then studied at the University of Chicago, presumably in pursuit of his master’s degree. Long earned teaching credentials in history, civics, English, music and mathematics.

Perhaps the most unusual feature of the Indianapolis production was the choice of the lead actor chosen to portray Brutus Jones. Arthur Theodore Long was born on December 31, 1884, the son of Henry and Nattie (Buckner) Long in Morrillton, Arkansas. According to the 6th edition of “Who’s Who in Colored America (1941-1944)”, Long graduated from Sumner High School in St. Louis, Missouri in 1904. He entered the University of Illinois at age twenty and earned a BA degree in 1908. Arthur then went on to further his education at both Indiana and Butler universities. He then studied at the University of Chicago, presumably in pursuit of his master’s degree. Long earned teaching credentials in history, civics, English, music and mathematics.