Original publish date: January 25, 2011 Reissue date: June 25, 2020

To most Hoosiers, nay Americans, the name Little Orphan Annie conjures up images of Sunday morning comic strips, ghost story telling nannies or a tiny prepubescent red headed girl singing “The sun will come out tomorrow” in a voice that could shatter glass. But to me, when I hear the name Little Orphan Annie I think of a lonely little graveyard a few miles from Indianapolis’ eastside between Cumberland and Greenfield on the Historic National Road.

Its in this forgotten little graveyard, known locally as Spring Lake cemetery, that you will find the mortal remains of an Indiana legend. On the west edge of the small signless boneyard, rests the gravestone of Mary Alice Gray with a plaque behind it identifying her as the inspiration for the 1885 poem, “Little Orphant Annie” by Poet James Whitcomb Riley. It is likely that you’ve driven past this innocuous little burial ground many times never caring it was there, much less aware of the story of its most celebrated internee.

Mary Alice “Allie” Smith was born the youngest of 10 children near Liberty Indiana on the 25th day of September in 1850. By all accounts, she lived happily on her small family farm until both of her parents died by the time Allie was about nine years old. What we know is that during the American Civil War in the winter of 1862, Mary Alice came to live with the Riley family in Greenfield. Allie was an orphan and the Rileys took her in to help with some of the work.

What we don’t know is how Allie came to the Riley home. Depending on who you talk to, Allie was; a friend of the family, a castoff of the Orphan Train movement (1854-1929), or she was brought to the home by her uncle, John Rittenhouse, who brought the young girl to Greenfield where he “dressed her in black” and “bound her out to earn her board and keep”. Ultimately, Mary Alice was taken in by Captain Reuben Riley as a servant to help his wife Elizabeth with the housework and her four children; John, James, Elva May and Alex.

What we don’t know is how Allie came to the Riley home. Depending on who you talk to, Allie was; a friend of the family, a castoff of the Orphan Train movement (1854-1929), or she was brought to the home by her uncle, John Rittenhouse, who brought the young girl to Greenfield where he “dressed her in black” and “bound her out to earn her board and keep”. Ultimately, Mary Alice was taken in by Captain Reuben Riley as a servant to help his wife Elizabeth with the housework and her four children; John, James, Elva May and Alex.

At first, the Riley family referred to Mary as a “guest”, but soon she was as loved as any other member of the family. The good-natured Ms. Riley taught her young charge how to do housework so that she would have a trade to sustain her. Mary quickly developed a strong bond with young James Whitcomb Riley or “Bud” as the family called him. Mary became like an older sister and soon her tales of “fairies, wunks, dwarfs, goblins and other scary beings” became part of the budding poet’s life.

On her first night in the Riley home, Allie refused to go to sleep and kept returning to the front hall to walk up and down the curved, handmade staircase, talking to herself all the while. One of her duties was to polish these stairs and as she did, she would kneel down and place her face close to each step as she gently rubbed it and called it by name. She was so fascinated with the steps, she told the children that fairies lived under each tread and she made up names for each of the fairies.”This one’s Clarabelle, and this one’s Annabelle, and here is Florabell.”

Although the names of the steps have been lost to history, tour guides at the Riley home believe some of them may have been Biblical names because Allie’s mother so often read the Bible to her daughter. By all accounts, Allie was a bright, creative youngster who kept herself entertained during the drudgery of everyday common household chores by making her work fun. Allie was an ideal babysitter who made up wild tales about the world around her and shared them with the Riley children, who were both thrilled and horrified by her stories. Her tales had a huge impact on young James and the imaginative verses changed the way he looked at the world forever.

When James was eleven, he asked Allie what he would be when he grew up. “Perhaps you’ll be a lawyer, like your father,” she suggested. “Or maybe someday, you’ll be a great poet.” Allie may have been the first to put this idea in James’ mind, but it is known that his mother and father were both gifted storytellers. Riley often shared his vivid childhood recollection of Allie climbing the stairs every night to her lonesome “rafter room” in the attic. And with every careful step leaning down and patting each stair affectionately as she called them by name.

When James was eleven, he asked Allie what he would be when he grew up. “Perhaps you’ll be a lawyer, like your father,” she suggested. “Or maybe someday, you’ll be a great poet.” Allie may have been the first to put this idea in James’ mind, but it is known that his mother and father were both gifted storytellers. Riley often shared his vivid childhood recollection of Allie climbing the stairs every night to her lonesome “rafter room” in the attic. And with every careful step leaning down and patting each stair affectionately as she called them by name.

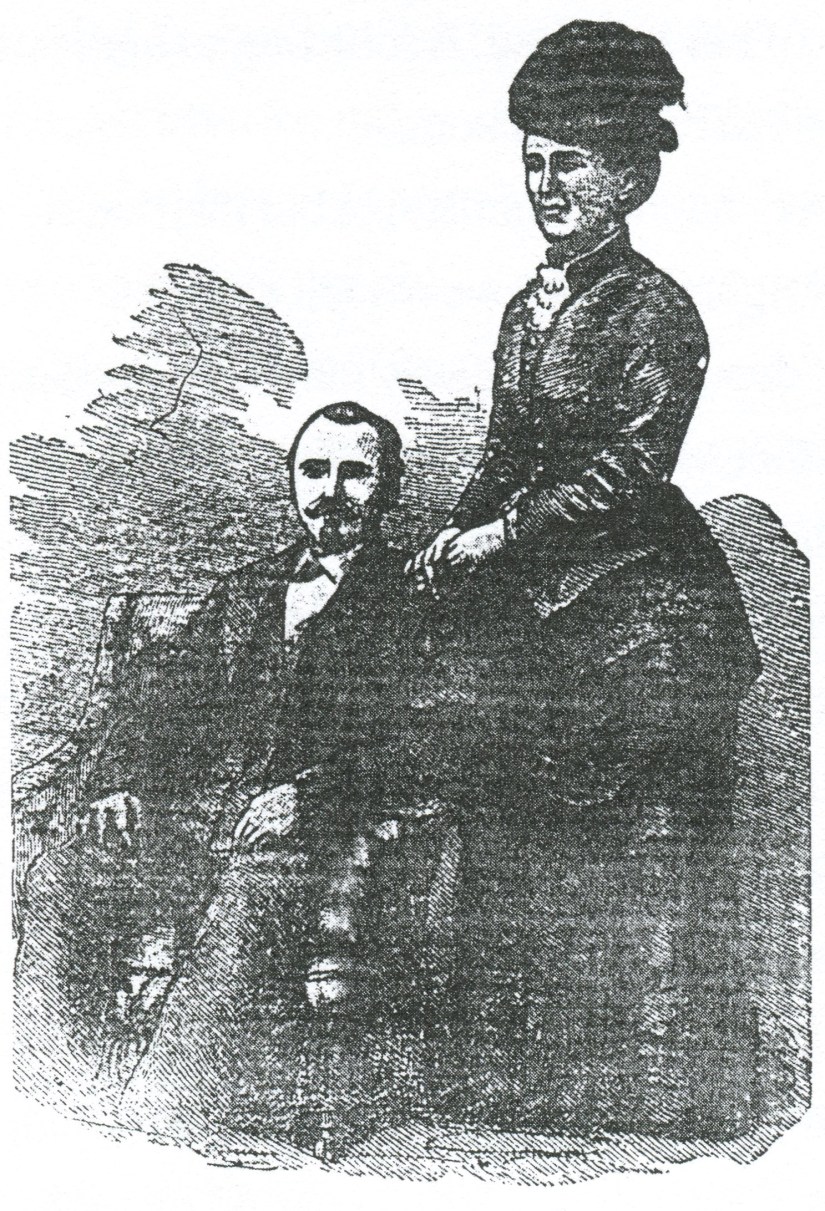

Young Allie used her storytelling gift to entertain the Riley children as they sat around the fireplace at night “listening to witch tales.” She used her fertile imagination to invent characters for use in her whimsical stories that resonated with the Riley children for the rest of their lives . She left the Riley home after only a year and never saw James again. On October 2, 1868, when she was 18, Allie married a local farmer named John Wesley Gray and lived on his farm not far south of Philadelphia until her husband’s death.

Although gone from Riley’s life at a young age, Allie’s impression on the poet was undeniable and years later he wrote a rhyme to honor his former friend, which he titled “Little Orphant Allie.” Published November 15, 1885 in the Indianapolis Journal and first titled “The Elf Child”, Riley changed the name to “Little Orphant Allie” at its third printing. Ironically, the publisher (Indianapolis Bobbs-Merrill) made an error and the poem was released with a typo and “Allie” became “Annie.” But for that typographical error she would have been known throughout the world as “Little Orphant Allie.” But when James Whitcomb Riley’s famous poem about the little homeless girl who “washed the cups and saucers up” was published and Riley found out how well it was selling, he decided not to tamper with revisions and Little Orphant Allie became Little Orphant Annie forever.

The “Hoosier poet” wrote his poems in nineteenth century Hoosier dialect, the language he’d heard growing up in the wild frontier of Greenfield. “Little Orphant Annie” contains four stanzas of twelve lines each; the first introduces Annie and the following three are stories she is telling to young children. The stories each tell of a bad child who is snatched away by goblins as a result of their misbehavior. The underlying moral and warning is announced in the final stanza, telling children that they should obey their parents and be kind to the unfortunate, lest they suffer the same fate. It remains one of Riley’s best loved poems among children in Indiana and is often associated with Halloween celebrations.

During the 1920s, the title became the inspiration for the names of the Sunday Funnies comic strip character Little Orphan Annie and the popular Raggedy Ann doll, created by fellow Indiana native and onetime Irvington resident Johnny Gruelle. And of course, in more modern times, it was made into a stage play and major motion picture called simply “Annie.”

I, like many fellow Hoosiers, am drawn to this particular poem because it was written to be recited aloud and not necessarily to be read from a page. Written in nineteenth century Hoosier dialect, the words can be difficult to read in modern times. Riley dedicates his poem “to all the little ones,” which immediately gets the attention of his intended audience; children. The alliteration, phonetic intensifiers and onomatopoeia add sing-song effects to the rhymes that become clearer when read aloud. The exclamatory refrain ending each stanza is urgently spoken adding more emphasis as the poem goes on. It is written in first person which makes the poem much more personal. Simply stated, the poem is read exactly as young “Bud” Riley recalled Allie telling it to him when he was a wide-eyed little boy.

I, like many fellow Hoosiers, am drawn to this particular poem because it was written to be recited aloud and not necessarily to be read from a page. Written in nineteenth century Hoosier dialect, the words can be difficult to read in modern times. Riley dedicates his poem “to all the little ones,” which immediately gets the attention of his intended audience; children. The alliteration, phonetic intensifiers and onomatopoeia add sing-song effects to the rhymes that become clearer when read aloud. The exclamatory refrain ending each stanza is urgently spoken adding more emphasis as the poem goes on. It is written in first person which makes the poem much more personal. Simply stated, the poem is read exactly as young “Bud” Riley recalled Allie telling it to him when he was a wide-eyed little boy.

Riley wrote another poem about her titled, “Where Is Mary Alice Smith?” In this poem he depicts the little orphan girl falling in love with a soldier boy who was killed during the war which caused her to die of grief. In truth, after leaving the Riley’s employ, Mary Alice went to work in a Tavern on the National Road in the town of Philadelphia where she met her husband John Gray and their marriage produced seven children.

Riley wrote another poem about her titled, “Where Is Mary Alice Smith?” In this poem he depicts the little orphan girl falling in love with a soldier boy who was killed during the war which caused her to die of grief. In truth, after leaving the Riley’s employ, Mary Alice went to work in a Tavern on the National Road in the town of Philadelphia where she met her husband John Gray and their marriage produced seven children.

Mary Alice Gray never realized that she was “Orphant Annie” until years after the poem was published. Riley tried in vain to locate her during his final years, going so far as to advertise widely in newspapers all over the Midwest. All the while never knowing that she was living just a few miles southwest of the old Riley homestead, leading the quiet life of a farmer’s wife. Riley was near death in Florida when Mrs. L.D. Marsh, Mary Alice’s daughter, saw one of the advertisements and contacted Riley to let him know the whereabouts of her mother. But by this time, the poet was too ill to make the trip to see her before his death.

Mary Alice Gray spoke of Riley frequently and delighted in telling about young “Bud’s” habit of writing verses and drawing pictures on the walls of the house, the porch, and the fence. Mary Alice passed away on Friday, March 7, 1924. Funeral services were held at 1 o’clock Sunday afternoon in Mrs. Marsh’s residence at 2225 Union Street and her burial was in Spring Lake Cemetery in Philadelphia. When she died, Ms. Gray’s obituary made the front page of The Indianapolis Star. Above her photo the headline read, “Little Orphant Annie Dies Suddenly.” On October 7, 1922, two years before her death and on what would have been Riley’s 73rd birthday, Ms. Gray took part in the ceremonial laying of the corner stone of the James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Hospital for Children. The legacy of “Little Orphant Annie,” however, has outlived both the poet and his muse.

The old Riley homestead in Greenfield is open to the public. The historic home is filled with lovely black walnut harvested from trees on the original property. After all these years, the deep brown, curving staircase still glistens in the morning sun making it very easy to imagine Allie sweeping the dirt off the steps and speaking to each one as she ascends. If you pause at the bottom of the stairs, you can almost imagine you hear the fairy voices.

Jut remember, as you travel out to the old Riley home on U.S. Highway 40 (the old National Road) you’re bound to pass through the remains of a little pike town called Philadelphia. The road starts to rise just past the Philadelphia signpost and there on the right is a small cemetery. Stop your car and walk towards the oldest headstones under the tall trees in back of the old burial ground. It is there that you will find the final resting place of Mary Alice Smith Gray, Riley’s beloved “Little Orphant Annie.” Its best you go before twilight though because should you delay past nightfall, “the Gobble-uns ‘at gits you ef you don’t watch out!”

Jut remember, as you travel out to the old Riley home on U.S. Highway 40 (the old National Road) you’re bound to pass through the remains of a little pike town called Philadelphia. The road starts to rise just past the Philadelphia signpost and there on the right is a small cemetery. Stop your car and walk towards the oldest headstones under the tall trees in back of the old burial ground. It is there that you will find the final resting place of Mary Alice Smith Gray, Riley’s beloved “Little Orphant Annie.” Its best you go before twilight though because should you delay past nightfall, “the Gobble-uns ‘at gits you ef you don’t watch out!”

In 1808, Irving created an updated version of Old St. Nick that rode over the treetops in a horse-drawn wagon “dropping gifts down the chimneys of his favorites.” Irving described Santa as a jolly Dutchman who smoked a long-stemmed clay pipe and wore baggy breeches and a broad-brimmed hat. Irving’s work also included the familiar phrase, “laying a finger beside his nose” some 14 years before a Troy, New York newspaper published the iconic children’s poem “Twas the night before Christmas,” which turned Santa’s wagon into a sleigh powered by reindeer.

In 1808, Irving created an updated version of Old St. Nick that rode over the treetops in a horse-drawn wagon “dropping gifts down the chimneys of his favorites.” Irving described Santa as a jolly Dutchman who smoked a long-stemmed clay pipe and wore baggy breeches and a broad-brimmed hat. Irving’s work also included the familiar phrase, “laying a finger beside his nose” some 14 years before a Troy, New York newspaper published the iconic children’s poem “Twas the night before Christmas,” which turned Santa’s wagon into a sleigh powered by reindeer. Irving’s stories are full of mistletoe and evergreen wreaths, Christmas candles and blazing Yule logs, singing and dancing, carolers at the door and the preacher at the church, wine and wassail, and, of course, the festive Christmas dinner. The description of Old Christmas as Irving experienced it in “Merrie Olde England,” helped to popularize these traditions in his native land.

Irving’s stories are full of mistletoe and evergreen wreaths, Christmas candles and blazing Yule logs, singing and dancing, carolers at the door and the preacher at the church, wine and wassail, and, of course, the festive Christmas dinner. The description of Old Christmas as Irving experienced it in “Merrie Olde England,” helped to popularize these traditions in his native land. The Yule-log is a great log of wood, sometimes the root of a tree, brought into the house on Christmas eve, laid in the fireplace, and lighted with a piece of last year’s log. While it burned there was great drinking, singing, and telling of tales. The Yule-log was to burn all night; if it went out, it was considered bad luck. If a squinting person come to the house while it was burning, or a barefooted person, it was considered bad luck. A piece of the Yule-log was carefully put away to light the next year’s Christmas fire.

The Yule-log is a great log of wood, sometimes the root of a tree, brought into the house on Christmas eve, laid in the fireplace, and lighted with a piece of last year’s log. While it burned there was great drinking, singing, and telling of tales. The Yule-log was to burn all night; if it went out, it was considered bad luck. If a squinting person come to the house while it was burning, or a barefooted person, it was considered bad luck. A piece of the Yule-log was carefully put away to light the next year’s Christmas fire.

Dickens’s memorable descriptions of Christmas scenes in “A Christmas Carol” owe a great deal to Irving. In February of 1842, while attending a New York dinner hosted by Irving, Dickens amusingly revealed his devotion to the great American author when he rose his glass in a toast and said, “I say, gentlemen, I do not go to bed two nights out of seven without taking Washington Irving under my arm upstairs to bed with me.”

Dickens’s memorable descriptions of Christmas scenes in “A Christmas Carol” owe a great deal to Irving. In February of 1842, while attending a New York dinner hosted by Irving, Dickens amusingly revealed his devotion to the great American author when he rose his glass in a toast and said, “I say, gentlemen, I do not go to bed two nights out of seven without taking Washington Irving under my arm upstairs to bed with me.” Irving’s descriptions of the short and cold winter days in his story “Old Christmas” make their way into the moral landscape lacking in Scrooge’s character in Dickens “A Christmas Carol”: “In the depth of winter, when nature lies despoiled of every charm, and wrapped in her shroud of sheeted snow, we turn for our gratifications to moral sources. The dreariness and desolation of the landscape, the short gloomy days and darksome nights, while they circumscribe our wanderings, shut in our feelings also from rambling abroad, and make us more keenly disposed for the pleasures of the social circle. Our thoughts are more concentrated; our friendly sympathies more aroused. We feel more sensibly the charm of each other’s society, and are brought more closely together by dependence upon each other for enjoyment. Heart calleth unto heart; and we draw our pleasures from the deep wells of living kindness, which lie in the quiet recesses of our bosoms; and which, when resorted to, furnish forth the pure element of domestic felicity.”

Irving’s descriptions of the short and cold winter days in his story “Old Christmas” make their way into the moral landscape lacking in Scrooge’s character in Dickens “A Christmas Carol”: “In the depth of winter, when nature lies despoiled of every charm, and wrapped in her shroud of sheeted snow, we turn for our gratifications to moral sources. The dreariness and desolation of the landscape, the short gloomy days and darksome nights, while they circumscribe our wanderings, shut in our feelings also from rambling abroad, and make us more keenly disposed for the pleasures of the social circle. Our thoughts are more concentrated; our friendly sympathies more aroused. We feel more sensibly the charm of each other’s society, and are brought more closely together by dependence upon each other for enjoyment. Heart calleth unto heart; and we draw our pleasures from the deep wells of living kindness, which lie in the quiet recesses of our bosoms; and which, when resorted to, furnish forth the pure element of domestic felicity.” Dickens Washington Irving inspired story popularized the phrase “Merry Christmas” and introduced the name ‘Scrooge’ and exclamation ‘Bah! Humbug!’ to the English language. However the book’s legacy is the powerful influence it has exerted upon its readers. A Christmas Carol” is widely credited with the “Spirit” of charitable giving associated so closely with the holiday today. Victorian Era examples can be found many places; in 1874, “Treasure Island” author Robert Louis Stevenson vowed to give generously after reading Dickens’s Christmas book, a Boston, Massachusetts merchant, expressed his generous hospitality by hosting two Christmas dinners after attending a reading of the book on Christmas Eve in 1867, and was so moved he closed his factory on Christmas Day and sent every employee a turkey and in 1901, the Queen of Norway sent gifts to London’s crippled children signed “With Tiny Tim’s Love.”

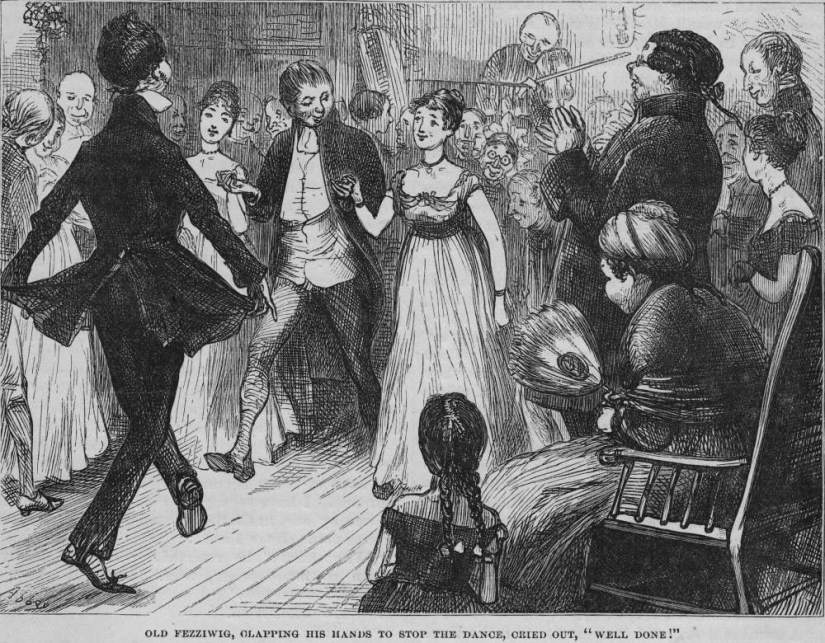

Dickens Washington Irving inspired story popularized the phrase “Merry Christmas” and introduced the name ‘Scrooge’ and exclamation ‘Bah! Humbug!’ to the English language. However the book’s legacy is the powerful influence it has exerted upon its readers. A Christmas Carol” is widely credited with the “Spirit” of charitable giving associated so closely with the holiday today. Victorian Era examples can be found many places; in 1874, “Treasure Island” author Robert Louis Stevenson vowed to give generously after reading Dickens’s Christmas book, a Boston, Massachusetts merchant, expressed his generous hospitality by hosting two Christmas dinners after attending a reading of the book on Christmas Eve in 1867, and was so moved he closed his factory on Christmas Day and sent every employee a turkey and in 1901, the Queen of Norway sent gifts to London’s crippled children signed “With Tiny Tim’s Love.” Speaking solely for myself, I often find myself drawing upon Dickens description of Old Fezziwig when I think of how others may observe me. In the novel, the Ghost of Christmas Past conjures up the memory of Scrooge’s old employer, Mr. Fezziwig, who converts his warehouse into a festive hall in which to celebrate Christmas: “Clear away. There is nothing they [Fezziwig’s employees] wouldn’t have cleared away, with old Fezziwig looking on. It was done in a minute. Every movable was packed off, as if it were dismissed from public life for evermore; the floor was swept and watered, the lamps were trimmed, fuel was heaped upon the fire; and the warehouse was as snug, and warm, and dry, and bright a ball-room, as you would desire to see upon a winter’s night.” Thus the ledger books, the daily grind, and the cold give way to music, dance, games, food, and fellowship.

Speaking solely for myself, I often find myself drawing upon Dickens description of Old Fezziwig when I think of how others may observe me. In the novel, the Ghost of Christmas Past conjures up the memory of Scrooge’s old employer, Mr. Fezziwig, who converts his warehouse into a festive hall in which to celebrate Christmas: “Clear away. There is nothing they [Fezziwig’s employees] wouldn’t have cleared away, with old Fezziwig looking on. It was done in a minute. Every movable was packed off, as if it were dismissed from public life for evermore; the floor was swept and watered, the lamps were trimmed, fuel was heaped upon the fire; and the warehouse was as snug, and warm, and dry, and bright a ball-room, as you would desire to see upon a winter’s night.” Thus the ledger books, the daily grind, and the cold give way to music, dance, games, food, and fellowship.

Although Lincoln was the first to officially recognize the U.S. holiday of Thanksgiving, Halloween was just beginning to take root during the Civil War. Some historians credit the Irish for “inventing” Halloween in the United States. Or more specifically, the Irish “little people” with a tendency toward vandalism, and their tradition of “Mischief Night” that spread quickly through rural areas. According to American Heritage magazine (October 2001 / Vol. 52, Issue 7), “On October 31, young men roamed the countryside looking for fun, and on November 1, farmers would arise to find wagons on barn roofs, front gates hanging from trees, and cows in neighbors’ pastures. Any prank having to do with an outhouse was especially hilarious, and some students of Halloween maintain that the spirit went out of the holiday when plumbing moved indoors.”

Although Lincoln was the first to officially recognize the U.S. holiday of Thanksgiving, Halloween was just beginning to take root during the Civil War. Some historians credit the Irish for “inventing” Halloween in the United States. Or more specifically, the Irish “little people” with a tendency toward vandalism, and their tradition of “Mischief Night” that spread quickly through rural areas. According to American Heritage magazine (October 2001 / Vol. 52, Issue 7), “On October 31, young men roamed the countryside looking for fun, and on November 1, farmers would arise to find wagons on barn roofs, front gates hanging from trees, and cows in neighbors’ pastures. Any prank having to do with an outhouse was especially hilarious, and some students of Halloween maintain that the spirit went out of the holiday when plumbing moved indoors.” So it is that the origins of our two most celebrated autumnal holidays trace their American roots directly to our sixteenth President. And no President in American history is more closely associated with ghosts than Abraham Lincoln. However, where did all of these Lincoln ghost stories originate? After all, they had to start somewhere because one thing is for certain, they didn’t come from Abraham Lincoln. Many historians believe that most of those stories (at least the Lincoln ghost stories in the White House) came from a middle-aged freedman born in Anne Arundel County Maryland who worked as a White House “footman” serving nine Presidents from U.S. Grant to Teddy Roosevelt. His duties as footman included service as butler, cook, doorman, light cleaning and maintenance.

So it is that the origins of our two most celebrated autumnal holidays trace their American roots directly to our sixteenth President. And no President in American history is more closely associated with ghosts than Abraham Lincoln. However, where did all of these Lincoln ghost stories originate? After all, they had to start somewhere because one thing is for certain, they didn’t come from Abraham Lincoln. Many historians believe that most of those stories (at least the Lincoln ghost stories in the White House) came from a middle-aged freedman born in Anne Arundel County Maryland who worked as a White House “footman” serving nine Presidents from U.S. Grant to Teddy Roosevelt. His duties as footman included service as butler, cook, doorman, light cleaning and maintenance.

Jeremiah would often spin yarns for visiting reporters. Most of these tall tales were pure Americana always designed to bolster the reputation of his employer and their families, but some of Jerry’s best remembered tales were spooky ghost stories. Smith claimed that he saw the ghosts of Presidents Lincoln, Grant, and McKinley, and that they tried to speak to him but only produced a buzzing sound.

Jeremiah would often spin yarns for visiting reporters. Most of these tall tales were pure Americana always designed to bolster the reputation of his employer and their families, but some of Jerry’s best remembered tales were spooky ghost stories. Smith claimed that he saw the ghosts of Presidents Lincoln, Grant, and McKinley, and that they tried to speak to him but only produced a buzzing sound.

One Chicago reporter said this about Smith: “He is a firm believer in ghosts and their appurtenances, and he has a fund of stories about these uncanny things that afford immense entertainment for those around him. But there is one idea that has grown into Jerry’s brain and is now part of it, resisting the effects or ridicule, laughter, argument, or explanation. He firmly believes that the White House is haunted by the spirits of all the departed Presidents, and, furthermore, that his Satanic majesty, the devil, has his abode in the attic. He cannot be persuaded out of the notion, and at intervals he strengthens his position by telling about some new strange noise he has heard or some additional evidence he has secured.”

One Chicago reporter said this about Smith: “He is a firm believer in ghosts and their appurtenances, and he has a fund of stories about these uncanny things that afford immense entertainment for those around him. But there is one idea that has grown into Jerry’s brain and is now part of it, resisting the effects or ridicule, laughter, argument, or explanation. He firmly believes that the White House is haunted by the spirits of all the departed Presidents, and, furthermore, that his Satanic majesty, the devil, has his abode in the attic. He cannot be persuaded out of the notion, and at intervals he strengthens his position by telling about some new strange noise he has heard or some additional evidence he has secured.”

If he was fearful, Joseph Brown did not show it as he sat down for what would be his last meal. At 5:30 PM, Mary Brown sent her two older children to the Smith’s, neighbors whose home was frequently visited by Wade, the children and Mary Brown. Mary instructed the children that she would come to get them after dinner and that Wade would play fiddle that evening to entertain at the Smith home. During the course of the evening, Wade asked Brown to borrow his buggy. He stated that he wanted to sell a horse to Irvington’s Dr. long. Brown agreed. As dinner ended, Brown went into the front yard to work on an ax handle. Wade was hitching the horse to the buggy.

If he was fearful, Joseph Brown did not show it as he sat down for what would be his last meal. At 5:30 PM, Mary Brown sent her two older children to the Smith’s, neighbors whose home was frequently visited by Wade, the children and Mary Brown. Mary instructed the children that she would come to get them after dinner and that Wade would play fiddle that evening to entertain at the Smith home. During the course of the evening, Wade asked Brown to borrow his buggy. He stated that he wanted to sell a horse to Irvington’s Dr. long. Brown agreed. As dinner ended, Brown went into the front yard to work on an ax handle. Wade was hitching the horse to the buggy. The investigation by Coroner George Wishard, namesake of today’s Wishard Hospital, was thorough and damning to Wade. During his investigation at the Brown farm, Wishard “found a board, probably a small kneading tray, hidden away under the shed… Which is bespattered with blood.” Signs of a violent struggle and blood were found in the yard. The mountain of evidence was building against Wade. But did he act alone? Or was “Bloody Mary” Brown, as one of the contemporary newspapers dubbed her, more involved than she claimed?

The investigation by Coroner George Wishard, namesake of today’s Wishard Hospital, was thorough and damning to Wade. During his investigation at the Brown farm, Wishard “found a board, probably a small kneading tray, hidden away under the shed… Which is bespattered with blood.” Signs of a violent struggle and blood were found in the yard. The mountain of evidence was building against Wade. But did he act alone? Or was “Bloody Mary” Brown, as one of the contemporary newspapers dubbed her, more involved than she claimed?