Original publish date: August 11, 2009

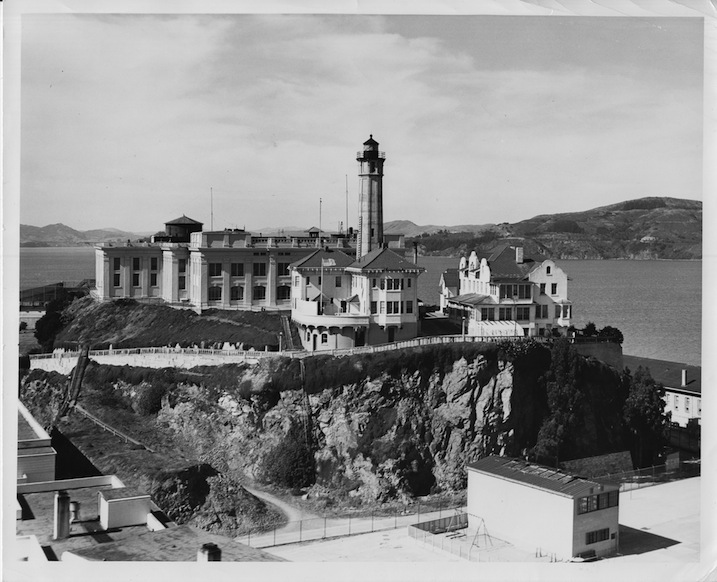

I first ran this article in 2009 on the 75th anniversary of an Alcatraz escape attempt by a desperate inmate with ties to fountain square. I thought it might be worth another read. Next week will mark the 84 years since the escape escape attempt. Since the time of my visit, the Island has changed much. The area where the escape attempt occurred, closed to the public back then, is now open to visitors.

Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary opened on August 11, 1934, exactly 75 years ago last week. I visited “The Rock” last Tuesday morning for an exclusive “Behind the Scenes” tour led by arguably the most famous face on the island, Emmy award winning park ranger John Cantwell. If you’ve ever seen a television program on the subject of Alcatraz, Cantwell’s face should be very familiar as he’s appeared in nearly every taped segment made on the island over the last dozen or so years. A Wisconsin native, Cantwell has worked for the National Park Service for almost 20 years having started as a clerk in the Alcatraz book store while still in high school. During his tenure, he has befriended over two dozen former inmates, countless former island residents and more than a dozen former guards, several of whom were like family to Cantwell often staying with John and his wife in their home while visiting the island for reunions and book signings. Sadly, the ranks of these former alumni have dwindled drastically in the last few years to the point that during the official 75th reunion ceremonies, only 5 former inmates and 2 former guards were in attendance.

The subject of my visit was a young man by the name of James A. Boarman, an Indianapolis bank robber with eastside ties who served two and one half years on “The Rock” from 1940 to 1943. James Arnold Boarman was born on November 3, 1919 in Whalen, Kentucky, the sixth of eight children. His father was a carpenter who died of an accidental drowning when James was only seven years old. His mother moved her brood to Indianapolis where all 9 family members shared residence in a small apartment on the cities’ southeast side. Young Jimmy Boarman attended St. Patrick’s Catholic School in Fountain Square until dropping out at age 14 when he got a job as a gardener to help support the family. His mother recalled that he was a “good boy” who didn’t mind turning his earnings over to her to help support the impoverished family.

At the age of 16, Jimmy was arrested for stealing an automobile, placed on probation and released to the custody of his sickly mother. However, he quickly stole two more cars (one in Indianapolis and another in Oklahoma) and, with two accomplices, headed to California where the trio was quickly apprehended. Unbeknownst to James, with this crime, he had graduated from a small time car thief to an enemy of the Federal Government by transporting a stolen car across state lines. His mother traveled west to plead for mercy for her son to no avail as James was sentenced to three years in Federal Prison in El Reno, Oklahoma. Boarman quickly became involved in several escape attempts and was considered such a high flight risk that he was transferred to the more secure facility at Lewisburg less than a year after arriving in the Sooner state. Unrepentant, James continued to fight, plot escape and hoard weapons until his release right up to his release in Christmas of 1939.

James headed back to Indianapolis and tried to “go straight” by getting a job at the RCA plant on Sherman Avenue. A series of layoffs and rehires pushed Boarman back into a life of crime. James was later quoted as saying: “When I came out of Lewisburg, I intended to go straight. I got me a job and did go straight. I lost that job, and couldn’t find another one for hell. I tried to join the Army, the Navy, and the Marine Corps and didn’t get in, so I went and got me a gun and started robbin’.” A sympathetic parole officer attempted to help Boarman in his quest to join the military by contacting recruiters directly, but the armed forces representatives felt that James’ past criminal conduct made him an unsuitable prospect for military induction. In August of 1940, James began what would be his last crime spree by stealing a car a gunpoint from an Indianapolis auto dealer and robbing the “Fletcher Trust Company” bank of $ 12,812 in cash. He was quickly arrested in Frankfort, Ky. after drawing attention to himself by spending over $1,000 of the stolen cash on a new car, firearms and several suits of flashy clothing.

When questioned by police, Boarman proudly claimed that while in town, he had amused himself by holding up several gas stations, grocery stores and “two ladies in a parking lot.” His F.B.I. report describes James as a “vicious menace to society… a highly unstable and impulsive youth…quite proud of the fact that he committed the instant offense without the aid or advice of others…He is convinced that he is entirely capable of whipping the whole world.” Sentenced to 20 years in Federal prison, true to form, James would again attempt escape while enroute back to Lewisburg by violently kicking the back of the driver’s seat of the police car transporting him, causing the car to veer off the road into a ditch. James struggled in a vain attempt to wrest the revolver away from the officer earning instead a one way ticket to Alcatraz, arriving 2 days before Halloween of 1940.

Boarman was a “Con’s Con”, generally well liked by his fellow inmates and always on the lookout for a viable escape plan. Ironically, Boarman would hatch his plan for freedom in early 1943 while working in the Island’s mat shop manufacturing cement ballast blocks for submarine nets used by the military during the war, the very same military that denied him employment as a citizen before his incarceration. Boarman, along with three other inmates, Harold Brest, Fred Hunter and Floyd Hamilton, would plan their escape for April of 1943. Brest was a kidnapper and bank robber destined to serve two separate stretches on the rock, Hunter was a member of the Ma Barker / Creepy Karpis kidnapping and robbery gang who made it to the F.B.I.’s legendary “Public Enemy” list, and Hamilton was one of the most famous men on Alcatraz at the time, a bank robber intimately linked to the famed 1930s outlaw couple “Bonnie & Clyde” and former “Public Enemy # 1” on the F.B.I. most wanted list of 1938. The four inmates planned their escape carefully and by April fool’s day were ready to go. However, Hoosier James Boarman insisted that they wait until the time and conditions were perfect for them to “Do the Houdini” and escape.

Tuesday April 13, 1945 dawned unusually cold with a dense layer of fog blanketing Alcatraz Island. The four convicts walked nervously down the narrow gravel road that led from the cell house to the mat shop located in the old “Model Industries Building” on the far northwest corner of the island. The building was built by the U.S. Military in the years that Alcatraz served as a disciplinary barracks before the Federal prison arrived in 1934 and as such was filled with many hidden corners and blind angles, not to mention a design flaw that seemingly allowed the back corner walls to drop directly into San Francisco Bay. The inmates had previously cut through the steel mesh covering the windows in preparation for their big moment. At 10:00 am, they made their move.

Tuesday April 13, 1945 dawned unusually cold with a dense layer of fog blanketing Alcatraz Island. The four convicts walked nervously down the narrow gravel road that led from the cell house to the mat shop located in the old “Model Industries Building” on the far northwest corner of the island. The building was built by the U.S. Military in the years that Alcatraz served as a disciplinary barracks before the Federal prison arrived in 1934 and as such was filled with many hidden corners and blind angles, not to mention a design flaw that seemingly allowed the back corner walls to drop directly into San Francisco Bay. The inmates had previously cut through the steel mesh covering the windows in preparation for their big moment. At 10:00 am, they made their move.

One of the guards, Custodial Officer George Smith, was overpowered by Hamilton, quickly tied up, gagged and dragged into a back room just as the Captain of the Guards, Henry Weinhold, a former Marine that the inmates called “Bullethead”, rounded the corner. James Boarman, armed with a knife and a hammer, began to beat the massive officer repeatedly with the heavy carpenter’s tool until finally subduing and tying him up to join his fellow guard now lying helpless on the floor. The inmates pushed the metal bars off the window and placed a cloth covered wooden ramp over the barbed wire fence located just a few feet from the window. The fugitive foursome then scooted carefully across the makeshift bridge and dropped to the narrow ledge below. The desperadoes, clad only in their underwear and leather belts, miraculously escaped grave injury during their bare-footed 30-foot plunge down a sheer cliff to the rock-strewn shore below. The quartet brought with them two empty cans designed to keep them afloat in the bay, each stuffed with stolen Army uniforms with which they hoped to make good their escape. Keep in mind that 1943 was the height of World War II and the shores of San Francisco Bay were lined with Army units and defense gun crews as well as being a major debarkation point for U.S. soldiers heading off to war in the Pacific theatre. Armed with the false confidence of their makeshift flotation devices and oblivious to the fact that they were surrounded by enough guns to fill an armory, the quartet hit the water.

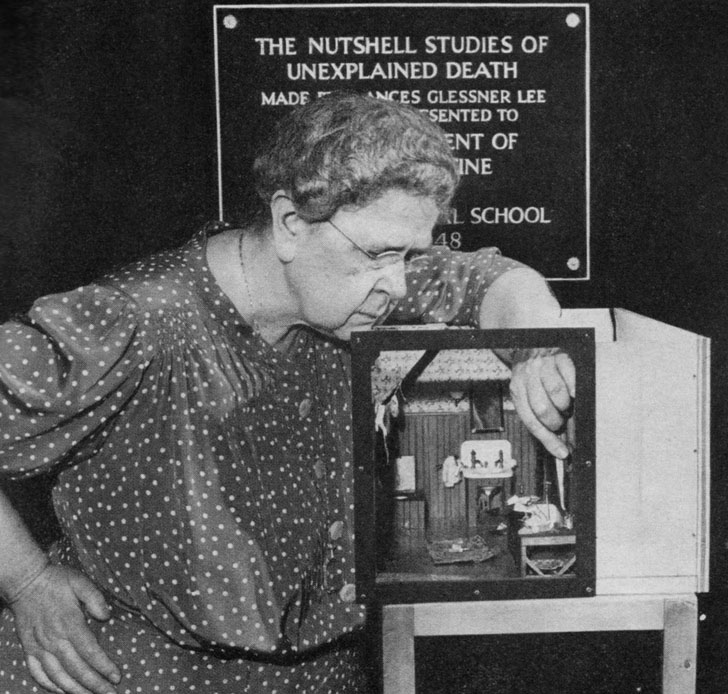

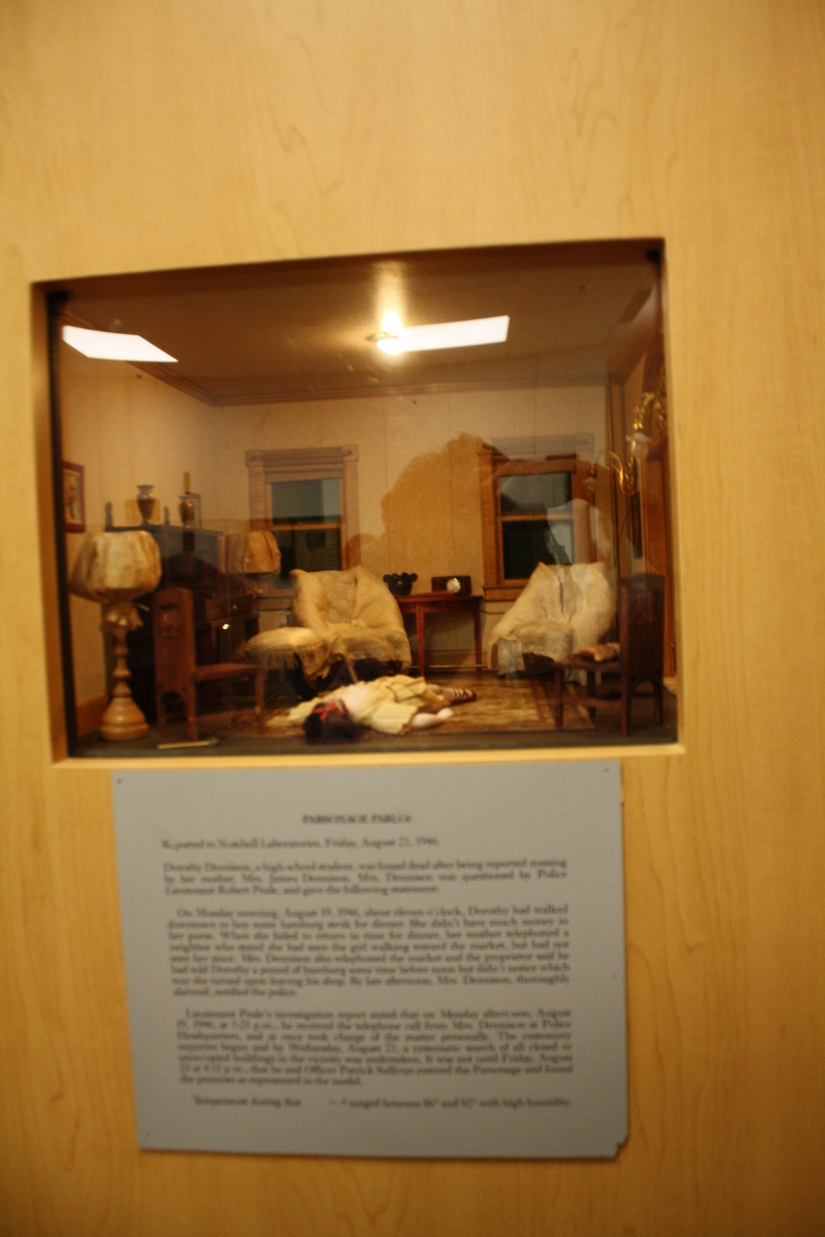

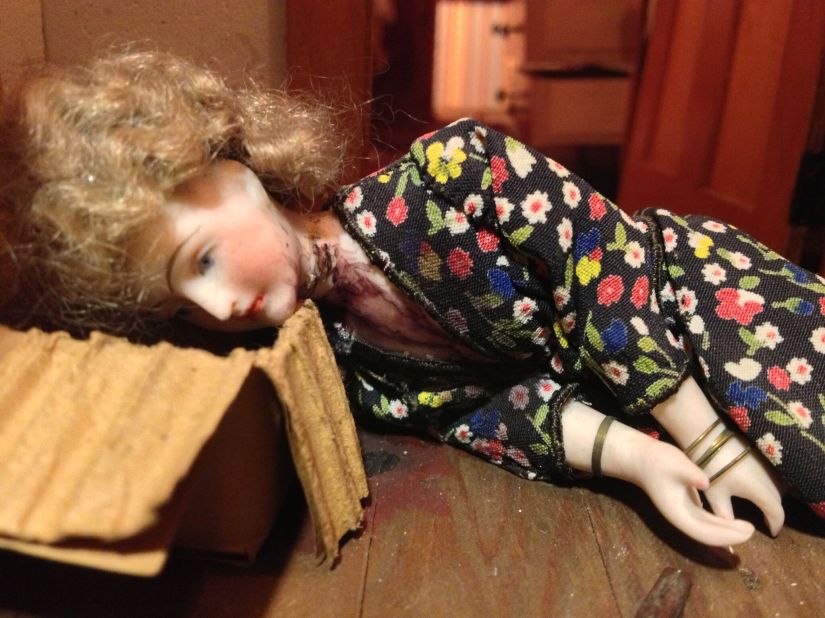

Housed in impressive looking wood and glass locked cases, they are not unlike the ancient penny arcade mechanical machines recalled by every baby boomer’s childhood. Except these scenes are populated by dead bodies, gruesome instruments of death and startling realistic blood spatter patterns. The scenes take place in attics, barns, bedrooms, log cabins, bathrooms, garages, kitchens, parsonages, saloons, jails, porches and even a woodman’s shack. Sometimes, it’s easy to determine the cause of death, but look closer and conclusions are tested. There is more than meets the eye in the Nutshell Studies and any object could be a clue. Every element of the dioramas-angles of minuscule bullet holes, placements of window latches, discoloration of painstakingly painted miniature corpses-challenges the powers of observation and deduction.

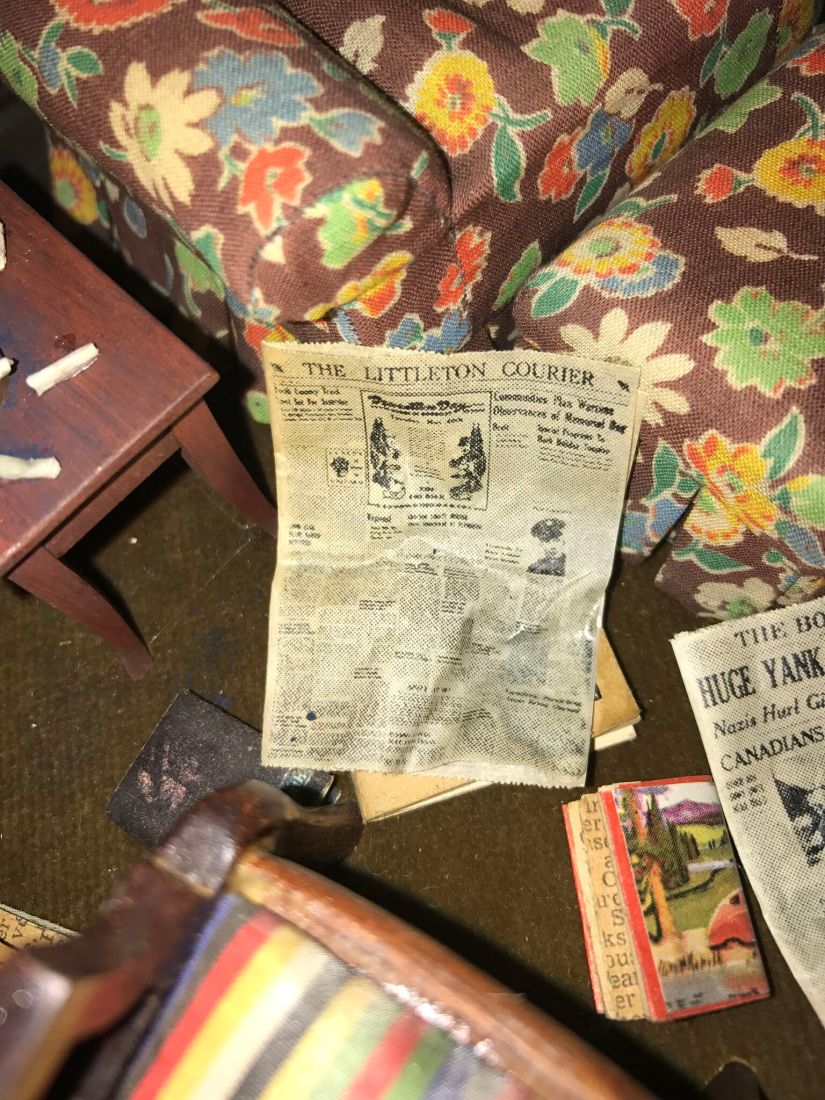

Housed in impressive looking wood and glass locked cases, they are not unlike the ancient penny arcade mechanical machines recalled by every baby boomer’s childhood. Except these scenes are populated by dead bodies, gruesome instruments of death and startling realistic blood spatter patterns. The scenes take place in attics, barns, bedrooms, log cabins, bathrooms, garages, kitchens, parsonages, saloons, jails, porches and even a woodman’s shack. Sometimes, it’s easy to determine the cause of death, but look closer and conclusions are tested. There is more than meets the eye in the Nutshell Studies and any object could be a clue. Every element of the dioramas-angles of minuscule bullet holes, placements of window latches, discoloration of painstakingly painted miniature corpses-challenges the powers of observation and deduction. Bruce says, “Look at the miniature sewing machine (about the size of your thumbnail) it’s threaded. There is graffiti on the jail cell walls. The newspapers (less than the size of a postage stamp) are real. Each one had to be printed on a tiny press, the newsprint is immeasurably small. The Life magazine cover is accurate to the week of the crime. The ant-sized cigarettes are hand rolled and burnt on the end. Amazing!” Bruce, who came to the M.E.’s office in 2012, says that although he’s been over every inch of each diorama, he is still making new discoveries.

Bruce says, “Look at the miniature sewing machine (about the size of your thumbnail) it’s threaded. There is graffiti on the jail cell walls. The newspapers (less than the size of a postage stamp) are real. Each one had to be printed on a tiny press, the newsprint is immeasurably small. The Life magazine cover is accurate to the week of the crime. The ant-sized cigarettes are hand rolled and burnt on the end. Amazing!” Bruce, who came to the M.E.’s office in 2012, says that although he’s been over every inch of each diorama, he is still making new discoveries.

The Nutshell Studies made their debut at the homicide seminar in Boston in 1945. It was the first of it’s kind. Bruce says, “Frances’ intention was for Harvard University to do for crime scene investigation what they had done for their famous business school. When Frances died in 1962, support evaporated and by 1966, the department of legal medicine at Harvard was dissolved.” When asked how the displays made the trip from Harvard yard to Baltimore, Bruce states, “That’s a good question. When Harvard planned to throw them away, longtime medical examiner Russell S. Fisher brought them here in 1968. Fisher was a legend and a former student of Frances Glessner Lee. Fisher was one of the doctors called in to examine John F. Kennedy’s head wounds.”

The Nutshell Studies made their debut at the homicide seminar in Boston in 1945. It was the first of it’s kind. Bruce says, “Frances’ intention was for Harvard University to do for crime scene investigation what they had done for their famous business school. When Frances died in 1962, support evaporated and by 1966, the department of legal medicine at Harvard was dissolved.” When asked how the displays made the trip from Harvard yard to Baltimore, Bruce states, “That’s a good question. When Harvard planned to throw them away, longtime medical examiner Russell S. Fisher brought them here in 1968. Fisher was a legend and a former student of Frances Glessner Lee. Fisher was one of the doctors called in to examine John F. Kennedy’s head wounds.”

When you hear the term “Gypsy”, what comes to mind? A vagabond road wanderer? A classic motorcycle? Maybe a Sonny and Cher song? Well, let me share with you a real gypsy story from a century ago that happened just up the National Road in Terre Haute. On May 16, 1914 three bodies were interred in “Terry Hot’s” Highland Lawn cemetery. According to newspaper accounts of the day, at the burial site “strange balls of incense” were placed around the graves. As the caskets were slowly lowered into the ground, veiled women wailed, tore at their clothing and pounded their chests. Their grief cut through the thick sickly sweet smoke hovering over the graves like a switchblade. When the graves were closed wine bottles were opened and their contents pored atop each grave in the shape of a cross.

When you hear the term “Gypsy”, what comes to mind? A vagabond road wanderer? A classic motorcycle? Maybe a Sonny and Cher song? Well, let me share with you a real gypsy story from a century ago that happened just up the National Road in Terre Haute. On May 16, 1914 three bodies were interred in “Terry Hot’s” Highland Lawn cemetery. According to newspaper accounts of the day, at the burial site “strange balls of incense” were placed around the graves. As the caskets were slowly lowered into the ground, veiled women wailed, tore at their clothing and pounded their chests. Their grief cut through the thick sickly sweet smoke hovering over the graves like a switchblade. When the graves were closed wine bottles were opened and their contents pored atop each grave in the shape of a cross. The May Day visit began like any other visit to town by the Gypsies. But Sunday May 3rd would prove to be an especially raucous day in camp. No-one knows what the Gypsies were celebrating, but celebrating they were. During the day (and through most of the night) 8 kegs of beer, wine and ale were consumed in camp. Neighbors reported the “camp was a scene of brawling and hilarity.” Eventually, most of the Gypsies passed out cold in their bunks. But in the predawn hours of Monday, one man still stalked the camp: John Demetro.

The May Day visit began like any other visit to town by the Gypsies. But Sunday May 3rd would prove to be an especially raucous day in camp. No-one knows what the Gypsies were celebrating, but celebrating they were. During the day (and through most of the night) 8 kegs of beer, wine and ale were consumed in camp. Neighbors reported the “camp was a scene of brawling and hilarity.” Eventually, most of the Gypsies passed out cold in their bunks. But in the predawn hours of Monday, one man still stalked the camp: John Demetro. Camp residents warned officers to be careful as Demetro was still stalking around the camp, most likely armed with his 16-shot Remington rifle, and was sure not to go down without a fight. Officers found him sitting in front of his tent, gun laid across his lap, staring blankly at the ground. Policemen cautiously approached, guns drawn, ready for a gunfight. But instead of resisting, Old John placidly handed over his gun and calmly surrendered. When they drew back the tent flap, they learned that Demetro had first bludgeoned, then shot, his wife to death. He then turned the gun on her father Bob Riska and shot Joe Riska in the face. Socca and Bob were DOA but Joe, despite missing half of his head, was still clinging to life. They took John to jail and Joe to the hospital were he died of his awful shotgun wound the next day.

Camp residents warned officers to be careful as Demetro was still stalking around the camp, most likely armed with his 16-shot Remington rifle, and was sure not to go down without a fight. Officers found him sitting in front of his tent, gun laid across his lap, staring blankly at the ground. Policemen cautiously approached, guns drawn, ready for a gunfight. But instead of resisting, Old John placidly handed over his gun and calmly surrendered. When they drew back the tent flap, they learned that Demetro had first bludgeoned, then shot, his wife to death. He then turned the gun on her father Bob Riska and shot Joe Riska in the face. Socca and Bob were DOA but Joe, despite missing half of his head, was still clinging to life. They took John to jail and Joe to the hospital were he died of his awful shotgun wound the next day. John Demetro’s wife and other victims lay in a Terre Haute Cemetery far from the lands of their birth. In Terre Haute’s Highland Cemetery Gypsies make almost annual pilgrimages to visit the graves each summer. Of course, there are numerous reports that the gravesites are haunted by “Gypsy Ghosts”, but most consider these stories as mere folklore designed to scare girlfriends and make kids nervously giggle. But, like every historical ghost story, there is truth behind the legend.

John Demetro’s wife and other victims lay in a Terre Haute Cemetery far from the lands of their birth. In Terre Haute’s Highland Cemetery Gypsies make almost annual pilgrimages to visit the graves each summer. Of course, there are numerous reports that the gravesites are haunted by “Gypsy Ghosts”, but most consider these stories as mere folklore designed to scare girlfriends and make kids nervously giggle. But, like every historical ghost story, there is truth behind the legend.

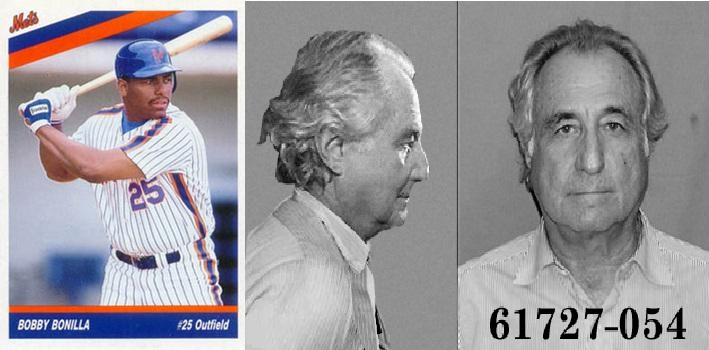

Many of these athletes are notoriously bad at managing their own money. Their teams often take care of all travel, meal and lodging expenses as part of their contracts. They see their salaries as instant, disposable income and make terrible investment decisions. When they retire or injury ends their career, they continue to spend wildly even though there is no more money coming in. Curt Schilling lost every cent of the $50 million he made playing baseball on a failed video game company. Allen Iverson squandered a $150 million fortune on gambling, houses, jewelry, child support and a 50-person entourage. Mike Tyson blew through a $300 million fortune. Evander Holyfield blew through a $250 million fortune. Phillies star Len Dykstra lost his fortune, then regained it only to lose it again. Locally, former Colts Quarterback Art Schlicter lost his fortune to drugs and gambling and he has been in-and-out of prison since his playing days ended.

Many of these athletes are notoriously bad at managing their own money. Their teams often take care of all travel, meal and lodging expenses as part of their contracts. They see their salaries as instant, disposable income and make terrible investment decisions. When they retire or injury ends their career, they continue to spend wildly even though there is no more money coming in. Curt Schilling lost every cent of the $50 million he made playing baseball on a failed video game company. Allen Iverson squandered a $150 million fortune on gambling, houses, jewelry, child support and a 50-person entourage. Mike Tyson blew through a $300 million fortune. Evander Holyfield blew through a $250 million fortune. Phillies star Len Dykstra lost his fortune, then regained it only to lose it again. Locally, former Colts Quarterback Art Schlicter lost his fortune to drugs and gambling and he has been in-and-out of prison since his playing days ended. $1.9 million annual salary a decade after an employee leaves the job? What does all that mean? Well, nothing really. That is nothing to everyone except Bobby Bonilla. Keep in mind that an average annual teacher’s salary in Indiana is $ 53,000, a Hoosier cop makes about $ 50.000, a Circle City Fireman makes about $ 45,000 and the President of the United States makes $ 400,000 per year. To me it means that it’s the Major League All-Star game break again and I felt like writing a baseball story. True, the Bonilla deal remains a trivial footnote from the pages of sports history, but it’s a footnote that I find infinitely interesting.

$1.9 million annual salary a decade after an employee leaves the job? What does all that mean? Well, nothing really. That is nothing to everyone except Bobby Bonilla. Keep in mind that an average annual teacher’s salary in Indiana is $ 53,000, a Hoosier cop makes about $ 50.000, a Circle City Fireman makes about $ 45,000 and the President of the United States makes $ 400,000 per year. To me it means that it’s the Major League All-Star game break again and I felt like writing a baseball story. True, the Bonilla deal remains a trivial footnote from the pages of sports history, but it’s a footnote that I find infinitely interesting. Original publish date: February 19, 2016

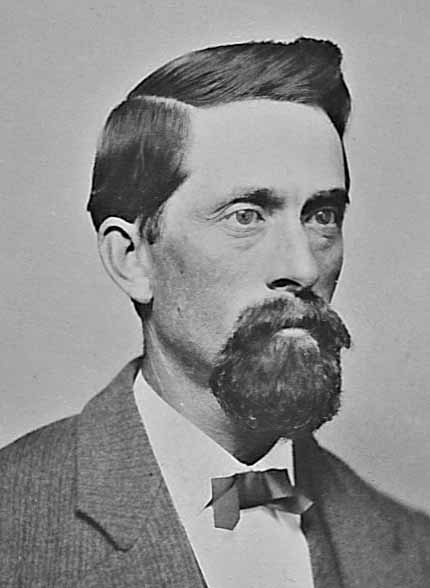

Original publish date: February 19, 2016 That afternoon, Booth sat down and wrote a letter to the editor of a Washington D.C. newspaper called the National Intelligencer. In it, he explained that his plans had changed from kidnapping Lincoln to assassinating Lincoln. He signed the letter not only with his own name but also three of his co-conspirators: Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, and David Herold. Then he got up and walked his rented horse down Fourteenth Street.

That afternoon, Booth sat down and wrote a letter to the editor of a Washington D.C. newspaper called the National Intelligencer. In it, he explained that his plans had changed from kidnapping Lincoln to assassinating Lincoln. He signed the letter not only with his own name but also three of his co-conspirators: Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, and David Herold. Then he got up and walked his rented horse down Fourteenth Street.

Apparently Booth visited Mathews and Warwick at the Petersen house and both rented the Lincoln death room on numerous occasions. Both actors recalled Booth visiting them there, stretching out on the bed, laughing and telling stories, chomping on a cigar or with his pipe hooked in his mouth. There are several unconfirmed claims that Mathews was actually staying in an upstairs room at the Petersen House on the night of Lincoln’s assassination. The accounts are speculative at best but tantalizing to be sure. If that were the case, then Mathews burned Booth’s confessional letter in a fireplace just feet away from the dying President.

Apparently Booth visited Mathews and Warwick at the Petersen house and both rented the Lincoln death room on numerous occasions. Both actors recalled Booth visiting them there, stretching out on the bed, laughing and telling stories, chomping on a cigar or with his pipe hooked in his mouth. There are several unconfirmed claims that Mathews was actually staying in an upstairs room at the Petersen House on the night of Lincoln’s assassination. The accounts are speculative at best but tantalizing to be sure. If that were the case, then Mathews burned Booth’s confessional letter in a fireplace just feet away from the dying President.