Original publish date: May, 2014 Reissue date: October 3, 2019

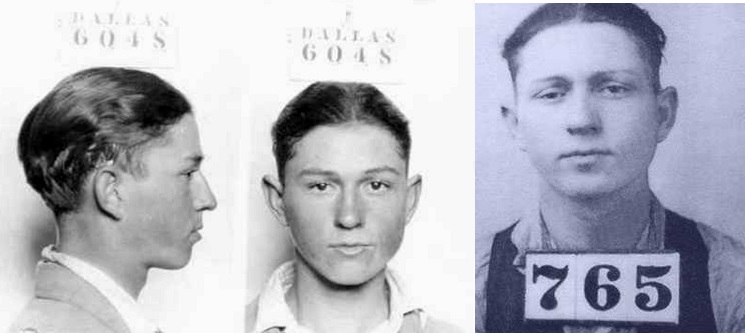

The ambush of Bonnie and Clyde some 80 years ago this month proved to be the beginning of the end of the “Public Enemy” gangster era of the 1930s. By the time of their bloody, bullet riddled deaths on May 23, 1934, new federal statutes made bank robbery and kidnapping federal offenses; and the growing relationship between local jurisdictions and the FBI, plus two-way radios in police cars, combined to make the outlaw bandit sprees much more difficult to carry out. Two months after the Bonnie and Clyde massacre, Hoosier John Dillinger was ambushed and killed in a Chicago alleyway beside the Biograph theatre; three months later, Charles Arthur “Pretty Boy” Floyd was killed by 14 FBI bullets fired into his back in a Clarkson, Ohio cornfield; and one month after that, Lester Gillis, aka “Baby Face Nelson”, shot it out, and lost, in Barrington, Illinois.

Everyone knows of Dillinger’s connection to our state and city. Many know that Pretty Boy Floyd spent time here assisting Dillinger in the robbery of an East Chicago bank on January 15, 1934 where Police Sargent William Patrick O’Malley died at the hands of the gang. Devoted Hoosier crime buffs also recognize that Baby Face Nelson coasted through the state during a robbery of the Merchants National Bank in South Bend on June 30, 1934, during which a police officer was shot and killed. But what about Bonnie & Clyde? Do they have Indiana connections?

Of course! The more your research, the more you find that EVERYTHING has an Indiana connection. For one, the posse that signed on to hunt down the duo to the death, led by the legendary Frank Hamer, had begun tracking the pair on February 12, 1934. Hamer studied the gang’s movements and found they swung in a circle skirting the edges of five Midwestern states, including Indiana, exploiting the “state line” rule that prevented officers in one jurisdiction from pursuing a fugitive into another. Barrow was a master of that pre-FBI rule, but he became quite predictable in his movements, so the experienced Hamer charted his path and easily predicted where he would go next.

On May 12, 1933, during Hamer’s heightened observation, Bonnie and Clyde and the Barrow Gang robbed the Lucerne State Bank in Lucerne Indiana. Some say the gang netted $300, other accounts say they left empty-handed. Lucerne, an unincorporated community founded by Swiss immigrants in Cass County, seems to have forgotten their connection to the deadly duo.

On Thursday May 11, Clyde and Buck cased the place. Later that night, Bonnie dropped the pair off and drove their most recent stolen Ford V-8 out of sight. The duo broke into the building and waited for clerks to arrive to open the bank in the morning. Clyde figured that he could get the drop on the unsuspecting employees before customers arrived to interfere. Great idea, in theory at least. Turns out, it was a fiasco.

Employees Everett Gregg and Lawson Selders arrived at 7:30 Friday morning. As soon as the tellers entered the room, closing the door behind them, the Barrow boys jumped out from their hiding places, ordering the startled workers to put their hands up. But this was 1933 and the rash of bank robberies across the state had made everyone jumpy. The bank managers had hidden a shotgun behind the cashier’s desk. Seems that although the Barrow brothers were alone in the building for hours before the robbery, neither thought to search the place. Cashier Gregg and the Barrow boys exchanged several shots, but no one was hit.

Charging to the sound of the gunfire, Bonnie and Buck’s wife Blanche roared to the rescue in their Flathead Ford. Bonnie was driving. The girls expected to see the boys running out of the bank, arms full of bank bags stuffed with cold hard cash. Instead, their husbands came sprinting towards them firing wildly over their shoulders apparently empty handed. Clyde jumped into the driver’s seat and, despite his well known prowess as a world class driver, getting out of town proved as difficult as the robbery. Locals were out for their morning stroll as the car roared through the small town.

One good citizen deduced that there was a robbery in progress. He quickly picked up a large chunk of wood and threw it in front of the speeding automobile. Clyde swerved into a nearby yard to avoid it. Another man jumped onto the hood of the Ford and Clyde yelled at Bonnie to “shoot him, shoot him!” She grabbed a gun and began to shoot, but failed to hit her prey. The ersatz hitchhiker fled in panic, gunpowder peppered through his thinning white hair. Bonnie later told her family that she deliberately missed because she “didn’t want to hurt an old man.”

By now, the whole town of Lucerne seemed to be descending on the outlaws. Guns were sprouting out of every doorway as nervous townsfolk took potshots at the fleeing robbers. Trouble was, the outlaws were shooting back. Two women, Ethel Jones and Doris Minor, were slightly wounded in the melee. The women were luckier than the livestock though. Clyde plowed his car straight through a pack of hogs, killing two of them, making these the only fatalities of the encounter. By all accounts, the robbery did not go well and Clyde, with Bonnie, his brother Buck and Blanche, had to shoot their way out of town for a paltry reward. According to the official Lucerne report in the FBI files, the gang’s getaway car was recovered in Rushville a couple days later.

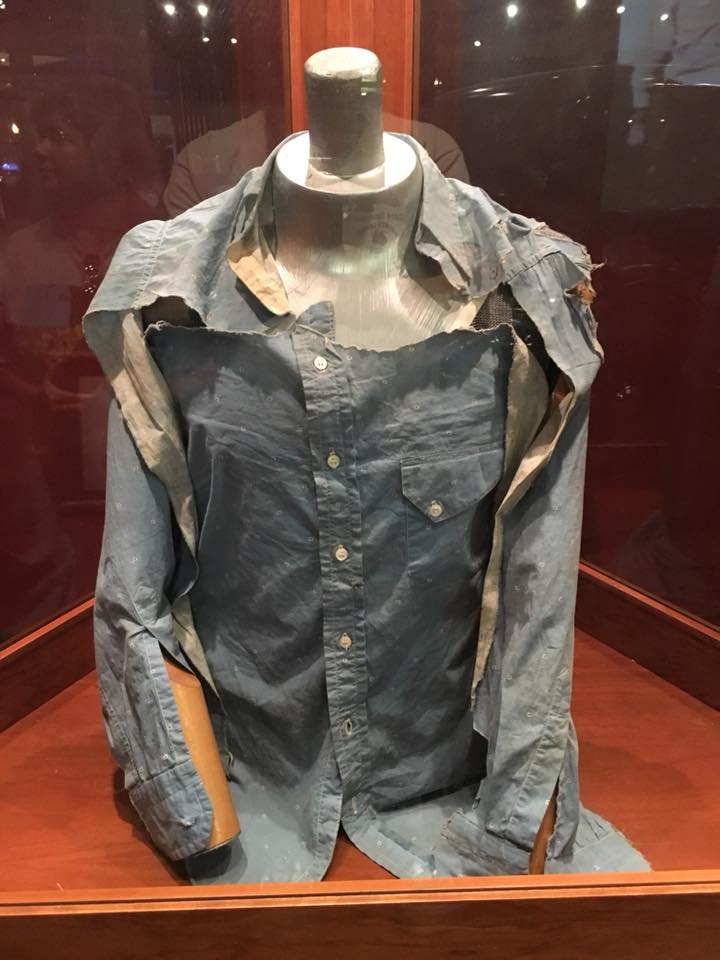

Evidently, perhaps hyped by their adrenaline infused escape, Clyde and his crew stopped into Indianapolis to do some shopping before leaving the Hoosier state forever. As promised in part I of this story, the most famous grisly blood relic associated with Bonnie & Clyde came from a well known department store in downtown Indy. Clyde Barrow’s death shirt came from the H.P. Wasson and Company (aka Wasson’s department store) located at the intersection of Washington and Meridian Streets in Indianapolis.

Clyde was wearing a size 14-32 western style shirt of light blue cotton print with “one patch pocket and pearl buttons” when he was shot to death near Gibsland, Louisiana. The neck label on the shirt reads: “Wasson V Towne shirt/Indianapolis”. The shirt was removed from Clyde Barrow’s body by the coroner who performed the autopsy. Hit by over twenty rounds (Including buckshot), Clyde’s bullet-riddled body slumped against the shattered steering wheel, his 12-gauge shotgun, damaged by the gun fire, slid to the floorboard beside him. Bonnie, with a half-eaten sandwich and magazine at her side, was also struck over twenty times. Both of the star crossed lovers died instantly.

Clyde was wearing a size 14-32 western style shirt of light blue cotton print with “one patch pocket and pearl buttons” when he was shot to death near Gibsland, Louisiana. The neck label on the shirt reads: “Wasson V Towne shirt/Indianapolis”. The shirt was removed from Clyde Barrow’s body by the coroner who performed the autopsy. Hit by over twenty rounds (Including buckshot), Clyde’s bullet-riddled body slumped against the shattered steering wheel, his 12-gauge shotgun, damaged by the gun fire, slid to the floorboard beside him. Bonnie, with a half-eaten sandwich and magazine at her side, was also struck over twenty times. Both of the star crossed lovers died instantly.

The Clyde Barrow death shirt contains over 30 bullet or buckshot holes and the cuts made by the mortician when the shirt was removed. An inked inscription on the shirt tail reads: “This is Clyde Barrow’s shirt worn on May 23, 1934 when be was killed.” and is signed by his youngest sister Marie Barrow as its witness. Traces of bloodstains remain in Parts of fabric. The shirt was given to Clyde’s mother, Connie Barrow, after his death. Marie said her mother kept the shirt in a cedar chest for years before passing it on to her.

The shirt was sold, ironically, on tax day of 1997 by a San Francisco auction house. The bidding was fast and furious and in the end, a Nevada casino known as “Whisky Pete’s ” paid $85,000 for the bloodstained shirt. Much more than Clyde ever stole in his lifetime. That number does not include the $ 10,000 buyer’s premium. The rest of Clyde Barrow’s belongings including a belt and necklace made by Barrow while in prison, a handmade mirror and 17 Barrow family photos, brought $187,809, most of which went to Marie Barrow, Clyde’s sister (She died in 1999).

One of the more prized personal relics that hit the auction block that day was Clyde’s 17-jewel, 10-carat gold-filled Elgin pocket watch. Expected to bring in $3,000, it was sold to an anonymous phone bidder for $20,770, including buyers’ fees. All items in the Barrow lot sold for amounts in excess of their estimated value, often doubling and tripling those estimates. The remaining Barrow family was at the auction to take a final look at the items before they changed hands. That Elgin pocket watch had an “Indianapolis movement.” Did I mention that Wasson’s also sold pocket watches?

Next Week: Part III of Bonnie & Clyde-Saga of he Death Car

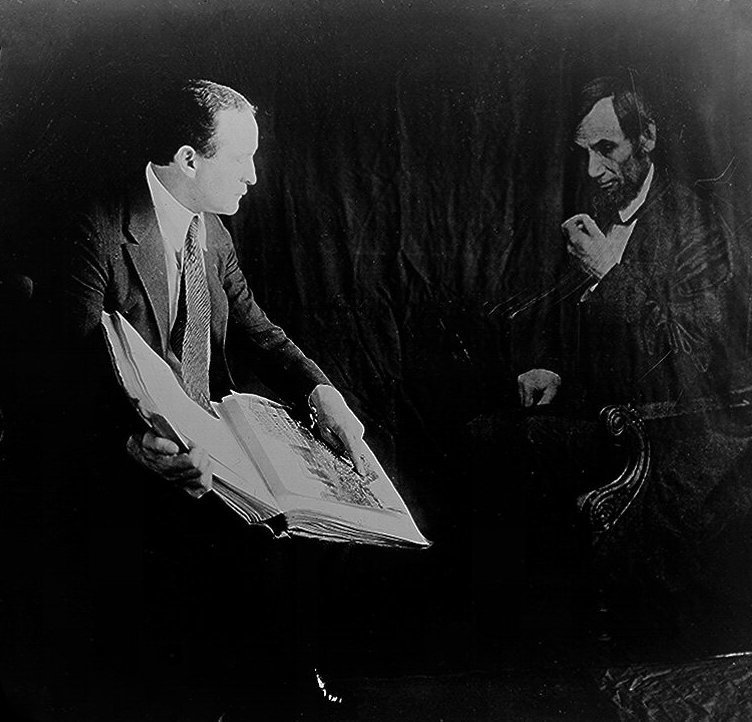

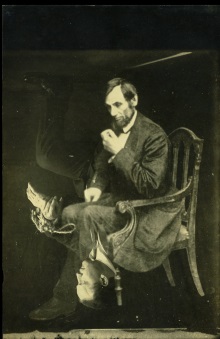

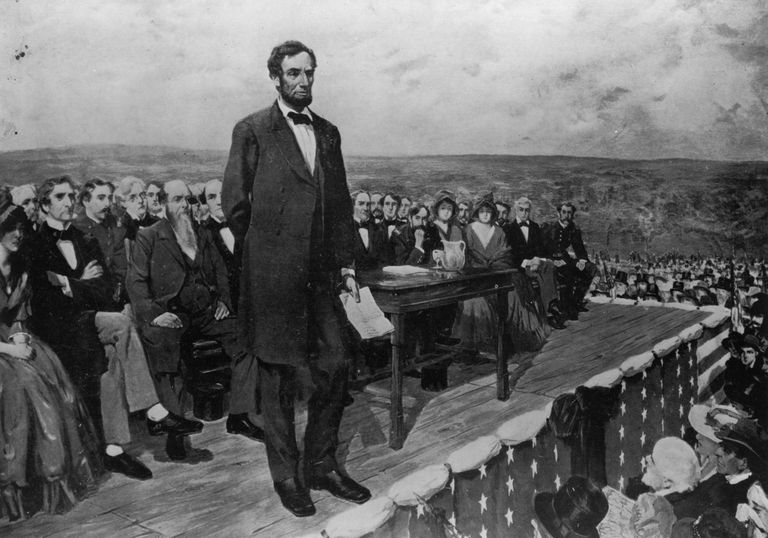

In Kenneth Silverman’s 1996 Biography “Houdini!!!: The Career of Ehrich Weiss : American Self-Liberator, Europe’s Eclipsing Sensation, World’s Handcuff King & Prison Breaker”, the author relays how Houdini referred to Lincoln as “my hero of heroes.” Houdini claimed to have read every book about Lincoln by the time he was a teenager. In William Kalush’s 2006 biography “The Secret Life of Houdini: The Making of America’s First Superhero”, there is a story of young Houdini attending a seance where the medium produced a message from our 16th President. Houdini, Lincoln expert that he was, then asked a question to Lincoln via the medium and was puzzled when the answer that came back was not correct. This encounter led to Houdini’s early discovery that most Spiritualists were fake.

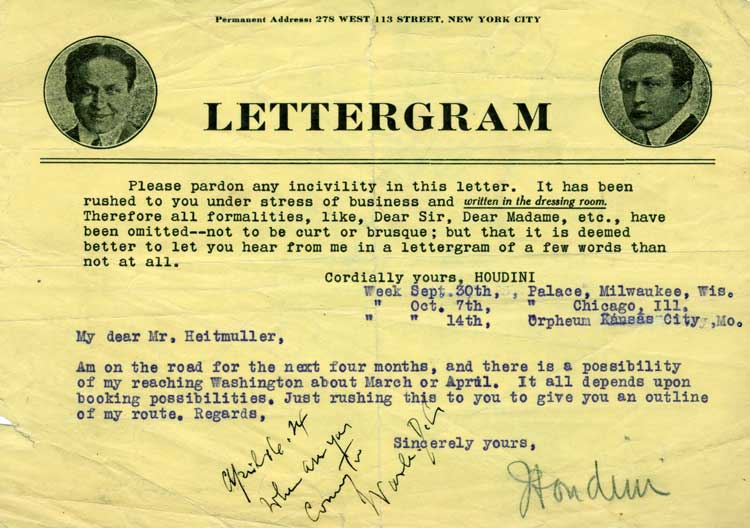

In Kenneth Silverman’s 1996 Biography “Houdini!!!: The Career of Ehrich Weiss : American Self-Liberator, Europe’s Eclipsing Sensation, World’s Handcuff King & Prison Breaker”, the author relays how Houdini referred to Lincoln as “my hero of heroes.” Houdini claimed to have read every book about Lincoln by the time he was a teenager. In William Kalush’s 2006 biography “The Secret Life of Houdini: The Making of America’s First Superhero”, there is a story of young Houdini attending a seance where the medium produced a message from our 16th President. Houdini, Lincoln expert that he was, then asked a question to Lincoln via the medium and was puzzled when the answer that came back was not correct. This encounter led to Houdini’s early discovery that most Spiritualists were fake. As he grew older and more financially secure, Houdini began to amass a personal collection of Lincoln memorabilia, particularly letters and autographs of the Great Emancipator. He also collected handwritten letters of every member of the assassin John Wilkes Booths family, several in response to letters sent by Houdini himself. Spending much of his adult life on the road, in hotels and traveling for days on ships and trains, Houdini became a prolific man of letters. One such letter survives that illustrates his desire and devotion to add to his Lincoln collection, despite the constraints of his vagabond lifestyle.

As he grew older and more financially secure, Houdini began to amass a personal collection of Lincoln memorabilia, particularly letters and autographs of the Great Emancipator. He also collected handwritten letters of every member of the assassin John Wilkes Booths family, several in response to letters sent by Houdini himself. Spending much of his adult life on the road, in hotels and traveling for days on ships and trains, Houdini became a prolific man of letters. One such letter survives that illustrates his desire and devotion to add to his Lincoln collection, despite the constraints of his vagabond lifestyle.

On Feb. 13, 1924, a day after the 115th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth, Houdini typed out a letter to Mary Edwards Lincoln Brown, the grand-daughter of Ninian and Elizabeth Edwards, Mary Lincoln’s sister. The letter, written from the dressing room of the State Lake Theatre in Chicago, Illinois, reads: “My dear Mrs. Brown: Enclosed you will find a Spirit Photograph of your renowned ancestor, and although the Theomonistic Society in Washington, D.C. claim that it is a genuine spirit photograph, as I made this one, you have my word for it, that it is only a trick effect. Mrs. Houdini joins me in sending you kindest regards, Sincerely yours, Houdini.”

On Feb. 13, 1924, a day after the 115th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth, Houdini typed out a letter to Mary Edwards Lincoln Brown, the grand-daughter of Ninian and Elizabeth Edwards, Mary Lincoln’s sister. The letter, written from the dressing room of the State Lake Theatre in Chicago, Illinois, reads: “My dear Mrs. Brown: Enclosed you will find a Spirit Photograph of your renowned ancestor, and although the Theomonistic Society in Washington, D.C. claim that it is a genuine spirit photograph, as I made this one, you have my word for it, that it is only a trick effect. Mrs. Houdini joins me in sending you kindest regards, Sincerely yours, Houdini.” Furthermore, Houdini also produced ‘fake spirit messages’ from Lincoln during his lectures to debunk spiritualism. Many spiritualists attempted to back up their fake photos and messages by claiming that Abraham Lincoln himself was a devoted spiritualist who had held seances in the White House. As proof, they cited a piece of British sheet music, published while Lincoln was President, which portrayed Honest Abe holding a candle while violins and tambourines flew about his head. The piece of music was called The Dark Séance Polka and the caption below the illustration of the president read “Abraham Lincoln and the Spiritualists”.

Furthermore, Houdini also produced ‘fake spirit messages’ from Lincoln during his lectures to debunk spiritualism. Many spiritualists attempted to back up their fake photos and messages by claiming that Abraham Lincoln himself was a devoted spiritualist who had held seances in the White House. As proof, they cited a piece of British sheet music, published while Lincoln was President, which portrayed Honest Abe holding a candle while violins and tambourines flew about his head. The piece of music was called The Dark Séance Polka and the caption below the illustration of the president read “Abraham Lincoln and the Spiritualists”.

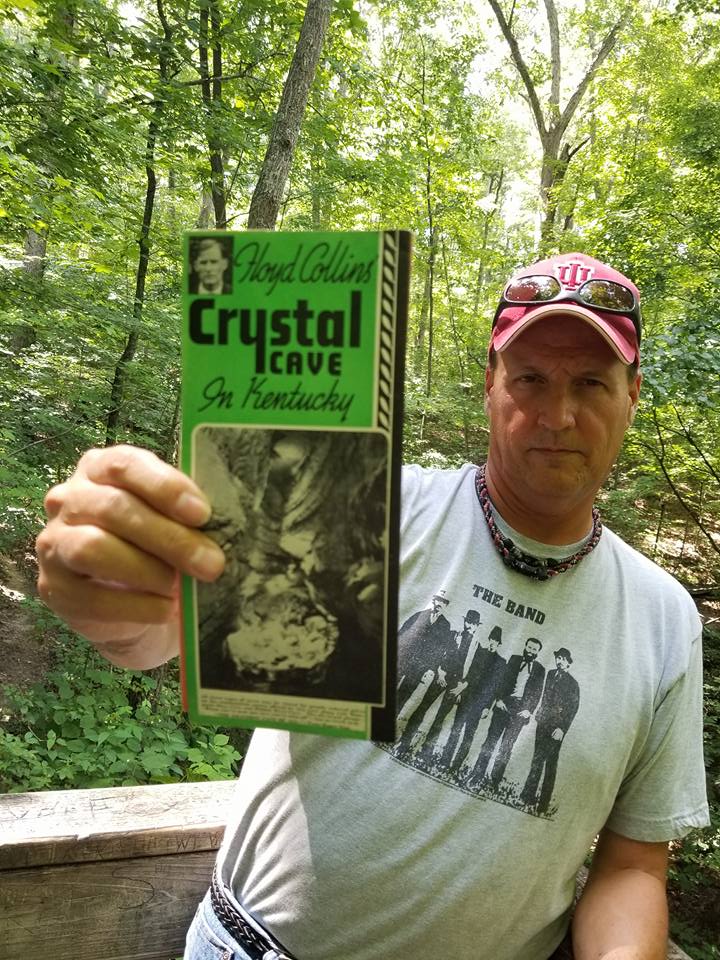

As springtime returned to the Kentucky hills, the Collins family melted back into their rocky, hillside farm; no richer from the limelight. After the crowds departed, locals saw old man Lee scouring the rescue site for glass bottles to return for deposit. Two years later, in 1927, a struggling Lee Collins sold Crystal Cave to a dentist named Dr. Harry B. Thomas. The sale included White Crystal cave and the burial site of Floyd Collins. Lee’s $10,000 deal with Dr. Thomas included a morbid clause: that his son’s body could be exhumed and displayed in a glass-covered coffin inside the cavern. The enterprising country doctor quickly dug the dead man up and placed Floyd’s encased body on display in Crystal Cave. The gimmick worked and, much to the horror of Floyd’s friends and the Collins family, tourists flocked to Crystal Cave to view the embalmed body of the man now known as the “Greatest Cave Explorer Ever Known.”

As springtime returned to the Kentucky hills, the Collins family melted back into their rocky, hillside farm; no richer from the limelight. After the crowds departed, locals saw old man Lee scouring the rescue site for glass bottles to return for deposit. Two years later, in 1927, a struggling Lee Collins sold Crystal Cave to a dentist named Dr. Harry B. Thomas. The sale included White Crystal cave and the burial site of Floyd Collins. Lee’s $10,000 deal with Dr. Thomas included a morbid clause: that his son’s body could be exhumed and displayed in a glass-covered coffin inside the cavern. The enterprising country doctor quickly dug the dead man up and placed Floyd’s encased body on display in Crystal Cave. The gimmick worked and, much to the horror of Floyd’s friends and the Collins family, tourists flocked to Crystal Cave to view the embalmed body of the man now known as the “Greatest Cave Explorer Ever Known.”

Sometime in the wee hours of March 18-19, 1929, Floyd’s body was stolen. The grave robbers “rescued” Collins’s corpse with the intentions of chucking him into the Green River, but Floyd’s body got tangled in the heavy underbrush and Dr. Thomas recovered the remains from a nearby field, minus his injured left leg. The remains were re-interned in a chained casket and placed in a secluded portion of Crystal Cave dubbed the “Grand Canyon”. A half-a-year later, the Great Depression blanketed the country and Floyd Collins’ saga was now a forgotten footnote. Times in Cave City got tough. Tourism plummeted-the same limelight that drew tourists innumerable to the Kentucky cave region now caused visitors to avoid it. As tourism dollars dried up, the sleazy tricks of local cave owners intensified. That feeling pervades Cave City today.

Sometime in the wee hours of March 18-19, 1929, Floyd’s body was stolen. The grave robbers “rescued” Collins’s corpse with the intentions of chucking him into the Green River, but Floyd’s body got tangled in the heavy underbrush and Dr. Thomas recovered the remains from a nearby field, minus his injured left leg. The remains were re-interned in a chained casket and placed in a secluded portion of Crystal Cave dubbed the “Grand Canyon”. A half-a-year later, the Great Depression blanketed the country and Floyd Collins’ saga was now a forgotten footnote. Times in Cave City got tough. Tourism plummeted-the same limelight that drew tourists innumerable to the Kentucky cave region now caused visitors to avoid it. As tourism dollars dried up, the sleazy tricks of local cave owners intensified. That feeling pervades Cave City today.

However, Paula’s younger sister Gail, (a Harvard graduate and architect who lives in Oakland, CA) caught the Collins’ family fever and is a caver. Paula explains, “she got the spelunking gene – she and her husband belonged to a Spelunking Club when she was in her 20s.” Gail states, “Floyd Collins was in a forbidden “sandstone” cave which is the most fragile of rocks. I only went into Limestone caves which are more stable. The biggest concern about spelunking in Indiana & Kentucky is flash flooding. We only did caving during the dry months and mostly winter, when the ground is frozen for 5-8 weeks at a time. I spent New Yea’s Eve in a cave with Chuck (her husband) and our Spelunking group one year. One of my last spelunking adventures I was pulled out of a very wet cave entry, by a caving buddy, 6’6″, 250 lb former Marine, because the makeshift tree trunk ladder was missing two rungs. He reached into the hole and used one arm to hoist me out. A harrowing adventure indeed.” Seems that Gail narrowly escaped the fate of her long lost cousin Floyd.

However, Paula’s younger sister Gail, (a Harvard graduate and architect who lives in Oakland, CA) caught the Collins’ family fever and is a caver. Paula explains, “she got the spelunking gene – she and her husband belonged to a Spelunking Club when she was in her 20s.” Gail states, “Floyd Collins was in a forbidden “sandstone” cave which is the most fragile of rocks. I only went into Limestone caves which are more stable. The biggest concern about spelunking in Indiana & Kentucky is flash flooding. We only did caving during the dry months and mostly winter, when the ground is frozen for 5-8 weeks at a time. I spent New Yea’s Eve in a cave with Chuck (her husband) and our Spelunking group one year. One of my last spelunking adventures I was pulled out of a very wet cave entry, by a caving buddy, 6’6″, 250 lb former Marine, because the makeshift tree trunk ladder was missing two rungs. He reached into the hole and used one arm to hoist me out. A harrowing adventure indeed.” Seems that Gail narrowly escaped the fate of her long lost cousin Floyd.

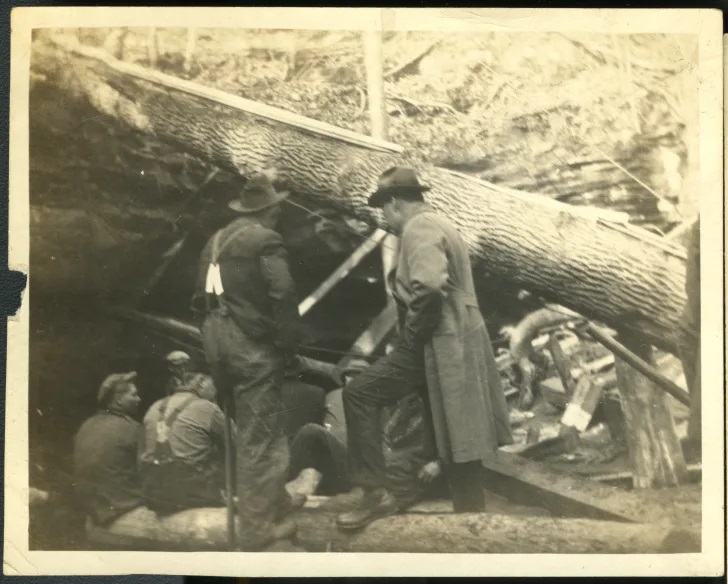

An enterprising local scientist jerry-rigged a wire to a lightbulb that was sent down to not only illuminate the hole, but also to keep Floyd warm. An amplifier on the other end was closely monitored by technicians hunched over an electronic box under the tarp. A cross between a telegraph and a stethoscope, it detected vibrations whenever Collins moved and was viewed as a desperate lifeline. The amplifier crackled 20 times per minute, which the scientist claimed as proof positive that Collins was still alive and breathing. Alive and breathing, but still trapped.

An enterprising local scientist jerry-rigged a wire to a lightbulb that was sent down to not only illuminate the hole, but also to keep Floyd warm. An amplifier on the other end was closely monitored by technicians hunched over an electronic box under the tarp. A cross between a telegraph and a stethoscope, it detected vibrations whenever Collins moved and was viewed as a desperate lifeline. The amplifier crackled 20 times per minute, which the scientist claimed as proof positive that Collins was still alive and breathing. Alive and breathing, but still trapped.

Floyd Collins is one of those people. Collins was long, lean, logical and legendary. He remains history’s most famous spelunker. Not only because of the way he lived, but also because of the way he died. William Floyd Collins was born on July 20, 1887 in Auburn, Kentucky. He was the third child of Leonidas Collins and Martha Jane Burnett. Collins had five brothers and two sisters, including another brother named Floyd. Which was not uncommon for the time as frontier families often feared that a child might not survive to adulthood.

Floyd Collins is one of those people. Collins was long, lean, logical and legendary. He remains history’s most famous spelunker. Not only because of the way he lived, but also because of the way he died. William Floyd Collins was born on July 20, 1887 in Auburn, Kentucky. He was the third child of Leonidas Collins and Martha Jane Burnett. Collins had five brothers and two sisters, including another brother named Floyd. Which was not uncommon for the time as frontier families often feared that a child might not survive to adulthood. The biggest business in the area was Mammoth Cave, but there were others: Great Onyx Cave, Colossal Cavern, Great Crystal Cave, Dorsey Cave, Salt Cave, Indian Cave, Parlor Cave, Diamond Cave, and Doyles Cave. These holes were all owned and operated by men who charged admission to the visiting tourists who were more than happy to pay for the privilege. At the center of it all was Cave City. Here was the depot that brought wealthy visitors in on the hour, all hungry for adventure. And Cave City residents were more than happy to assist these gullible visitors by relieving them of their cash. As we will see later in this article, not much has changed in 200 years.

The biggest business in the area was Mammoth Cave, but there were others: Great Onyx Cave, Colossal Cavern, Great Crystal Cave, Dorsey Cave, Salt Cave, Indian Cave, Parlor Cave, Diamond Cave, and Doyles Cave. These holes were all owned and operated by men who charged admission to the visiting tourists who were more than happy to pay for the privilege. At the center of it all was Cave City. Here was the depot that brought wealthy visitors in on the hour, all hungry for adventure. And Cave City residents were more than happy to assist these gullible visitors by relieving them of their cash. As we will see later in this article, not much has changed in 200 years.

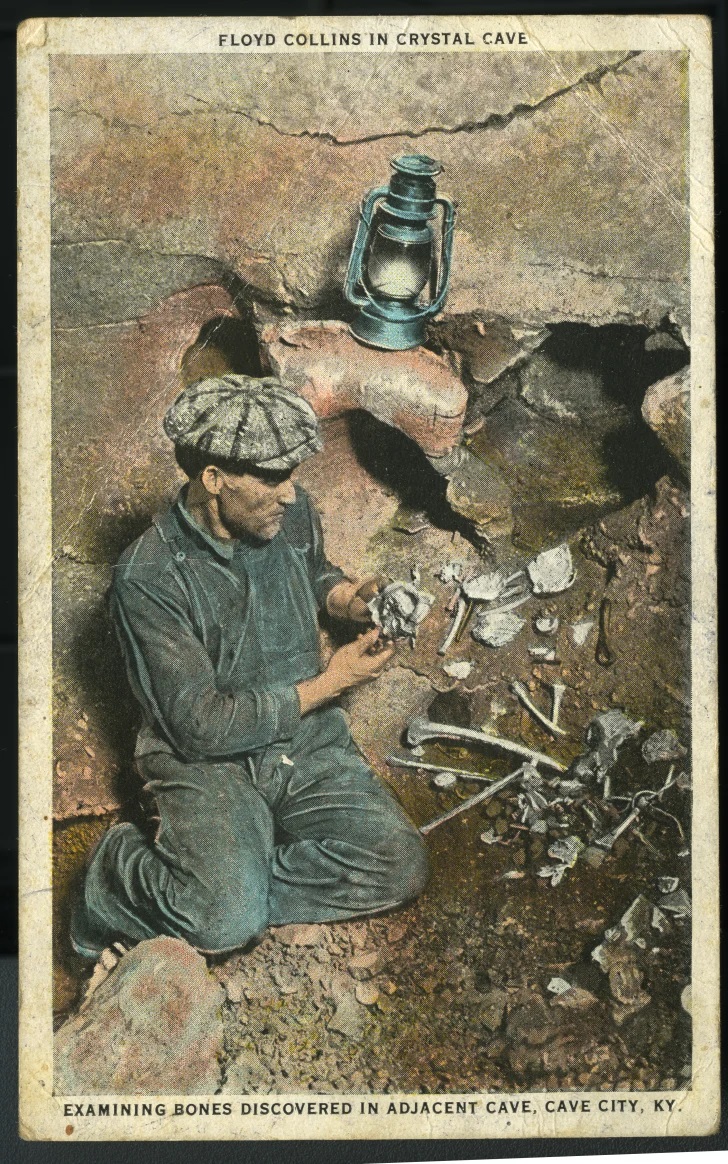

Collins first tasted celebrity when he discovered Crystal Cave in 1917 when he discovered Crystal Cave (now part of the Flint Ridge Cave System of the Mammoth Cave National Park). Twenty-seven year old Collins had chased a ground hog down a hole on his father’s farm. The hole turned out to be a passage to a large cavern Floyd called “White Crystal Cave”. He owned one half and his father owned the other. They went into business, selling options on the cave to a neighbor named Johnny Gerald who’d made a little money buying and selling tobacco. Johnny and Floyd took turns; one of them stood on the side of the road and tried to talk the tourists inside; the other guided them through the cave’s.

Collins first tasted celebrity when he discovered Crystal Cave in 1917 when he discovered Crystal Cave (now part of the Flint Ridge Cave System of the Mammoth Cave National Park). Twenty-seven year old Collins had chased a ground hog down a hole on his father’s farm. The hole turned out to be a passage to a large cavern Floyd called “White Crystal Cave”. He owned one half and his father owned the other. They went into business, selling options on the cave to a neighbor named Johnny Gerald who’d made a little money buying and selling tobacco. Johnny and Floyd took turns; one of them stood on the side of the road and tried to talk the tourists inside; the other guided them through the cave’s. Soon the Collins family found themselves smack dab in the middle of the “Cave Wars” of the early 1920s, where Central Kentucky cave owners and explorers entered into a bitter competition to exploit the bounty of caves for commercial profit. Trouble was, Crystal Cave was the last cave on the road from Cave City. By the time tourists discovered it, they were out of money and interest. During the Cave War years, cave owners competed bitterly among each other in order to bring in visitors. The most common tactic was to deploy a man, referred to as a “capper”, who would suddenly rush out of the bushes, hop onto your car’s running board along the rugged road out to Mammoth to excitedly inform you that Mammoth had collapsed or was under quarantine from Consumption (now known as Tuberculosis) and would persuade you to visit their cave instead.

Soon the Collins family found themselves smack dab in the middle of the “Cave Wars” of the early 1920s, where Central Kentucky cave owners and explorers entered into a bitter competition to exploit the bounty of caves for commercial profit. Trouble was, Crystal Cave was the last cave on the road from Cave City. By the time tourists discovered it, they were out of money and interest. During the Cave War years, cave owners competed bitterly among each other in order to bring in visitors. The most common tactic was to deploy a man, referred to as a “capper”, who would suddenly rush out of the bushes, hop onto your car’s running board along the rugged road out to Mammoth to excitedly inform you that Mammoth had collapsed or was under quarantine from Consumption (now known as Tuberculosis) and would persuade you to visit their cave instead.

Floyd was encased under a 4′ x 4′ square, two ton block of solid limestone ceiling, the sidewalls of the tunnel were composed of loose stones, pebbles, sand and mud. Floyd was careful to avoid bumping or displacing anything likely to cause a collapse. Collins made it through, muddy, soaked and sweating, after leaving his securely attached rope for a future trip into the 60-foot precipice he had yet to see. He wriggled head first back into the tight gravelly crevice leading to the steep, serpentine chute he’d just come in by. Pushing the kerosene lantern ahead of him as far as he could, he would then twist and squirm, shrugging ahead inch by inch till reaching the lantern before repeating the pattern by pushing ahead. Suddenly, Floyd’s lantern fell over, broke and went out.

Floyd was encased under a 4′ x 4′ square, two ton block of solid limestone ceiling, the sidewalls of the tunnel were composed of loose stones, pebbles, sand and mud. Floyd was careful to avoid bumping or displacing anything likely to cause a collapse. Collins made it through, muddy, soaked and sweating, after leaving his securely attached rope for a future trip into the 60-foot precipice he had yet to see. He wriggled head first back into the tight gravelly crevice leading to the steep, serpentine chute he’d just come in by. Pushing the kerosene lantern ahead of him as far as he could, he would then twist and squirm, shrugging ahead inch by inch till reaching the lantern before repeating the pattern by pushing ahead. Suddenly, Floyd’s lantern fell over, broke and went out.