Original publish date: March 7, 2019

So, what did you do for Abraham Lincoln’s birthday? Go out to dinner? Go to church? Get together with friends and family? Wait, you knew February 12th was Honest Abe’s birthday didn’t you? Well, don’t feel bad, nobody else did either. But once upon a time, everyone celebrated Lincoln’s birthday.

The move to celebrate Lincoln’s birthday began after his 1865 assassination. In December, the U.S. House of Representatives Select Committee agreed that Feb. 12, 1866 should be set aside for ceremonies in the House of Representatives. Lincoln’s secretary of war, Edwin Stanton, was asked to give a eulogy for Lincoln at the event. When the day arrived, the Capitol was closed to the public and guests filed into the House chamber for the commemoration, which began at noon. The president’s birthday was commemorated by both houses of Congress, the Cabinet, the Supreme Court, officers of the army and navy, and many foreign representatives.

Inside the House chamber guests listened to historian George Bancroft (former Secretary of the Navy and the man who established the Naval Academy at Annapolis) talk about “the life, character, and services of Lincoln…forming one of the most imposing scenes ever witnessed in the land.” The address took nearly two hours. The push for a formal celebration quickly spread to state capitals, legislatures and city councils. Most northern states quickly warmed to the idea but bitterness over Reconstruction and the cult of the “Lost Cause” among southerners scuttled attempts to make Lincoln’s birthday a Federal holiday.

Inside the House chamber guests listened to historian George Bancroft (former Secretary of the Navy and the man who established the Naval Academy at Annapolis) talk about “the life, character, and services of Lincoln…forming one of the most imposing scenes ever witnessed in the land.” The address took nearly two hours. The push for a formal celebration quickly spread to state capitals, legislatures and city councils. Most northern states quickly warmed to the idea but bitterness over Reconstruction and the cult of the “Lost Cause” among southerners scuttled attempts to make Lincoln’s birthday a Federal holiday.

Abraham Lincoln was born on Feb. 12, 1809 in Hodgenville, Kentucky, and to the first few generations after his assassination, that date on the calendar had meaning. Of the 48 states that made up the United States in 1940, exactly half celebrated Lincoln’s Birthday as a holiday. Most celebrations took place in schools, churches, veteran’s halls and political functions. Unlike other traditional American celebrations, Lincoln was not honored with parades but rather with ceremonial dinners and speeches. The states continued to recognize the holiday, which was in close proximity of Washington’s Birthday holiday less than two weeks later, for another 30 years until Congress stepped in and changed all that.

In 1971 Congress passed the Uniform Monday Holiday Act. The law shifted several holidays (Veteran’s Day, Washington’s Birthday, Memorial Day, Labor Day, Lincoln’s Birthday and Columbus Day to name a few) from specific days to a Monday. The reason behind the change was seen as a way to create more three-day weekends and reduce employee absenteeism. The birthdays of George Washington and Lincoln were only 10 days apart, so they were blended into Presidents’ Day.

In 1971 Congress passed the Uniform Monday Holiday Act. The law shifted several holidays (Veteran’s Day, Washington’s Birthday, Memorial Day, Labor Day, Lincoln’s Birthday and Columbus Day to name a few) from specific days to a Monday. The reason behind the change was seen as a way to create more three-day weekends and reduce employee absenteeism. The birthdays of George Washington and Lincoln were only 10 days apart, so they were blended into Presidents’ Day.

Eventually, individual states created their own Presidents’ Day holidays to be observed on the third Monday in February. This celebration has been enacted in some fashion by 38 states, though never federally, and each varies by state. Some mark the day as a specific remembrance of Washington and Lincoln while others view it as a day to recognize all U.S. presidents. Alabama celebrates Washington and Jefferson. A few states still recognize Lincoln’s birthday on February 12 as its own official holiday. Most notably, Kentucky, his birth state and Illinois,his adopted home state, both celebrate Lincoln’s birthday as an official state holiday, along with a few other states including New York, Connecticut, and Missouri. However, this number has declined in recent years, when California, Ohio and New Jersey ended the celebration of Lincoln’s birthday as paid holidays to cut budgetary costs. Unfortunately, more states now celebrate Black Friday as a holiday than celebrate Lincoln’s birthday. Indiana and Georgia are a couple states that recognize Lincoln’s Birthday on the day after Thanksgiving aka Black Friday.

Eventually, individual states created their own Presidents’ Day holidays to be observed on the third Monday in February. This celebration has been enacted in some fashion by 38 states, though never federally, and each varies by state. Some mark the day as a specific remembrance of Washington and Lincoln while others view it as a day to recognize all U.S. presidents. Alabama celebrates Washington and Jefferson. A few states still recognize Lincoln’s birthday on February 12 as its own official holiday. Most notably, Kentucky, his birth state and Illinois,his adopted home state, both celebrate Lincoln’s birthday as an official state holiday, along with a few other states including New York, Connecticut, and Missouri. However, this number has declined in recent years, when California, Ohio and New Jersey ended the celebration of Lincoln’s birthday as paid holidays to cut budgetary costs. Unfortunately, more states now celebrate Black Friday as a holiday than celebrate Lincoln’s birthday. Indiana and Georgia are a couple states that recognize Lincoln’s Birthday on the day after Thanksgiving aka Black Friday.

In most states, Lincoln’s birthday is not celebrated separately, as a stand-alone holiday. Instead Lincoln’s Birthday is combined with a celebration of President George Washington’s birthday (also in February) and celebrated either as Washington’s Birthday or as Presidents’ Day on the third Monday in February, concurrent with the federal holiday. Good for George Washington. Sad for Abraham Lincoln. Once upon a time, Lincoln’s birthday was a milestone for Americans to pause and honor greatness.

In most states, Lincoln’s birthday is not celebrated separately, as a stand-alone holiday. Instead Lincoln’s Birthday is combined with a celebration of President George Washington’s birthday (also in February) and celebrated either as Washington’s Birthday or as Presidents’ Day on the third Monday in February, concurrent with the federal holiday. Good for George Washington. Sad for Abraham Lincoln. Once upon a time, Lincoln’s birthday was a milestone for Americans to pause and honor greatness.

The centennial of Lincoln’s birth was the largest commemoration of any one person in American history. On the morning of February 12, 1909, the forts around New York Harbor, the National Guard field batteries, and the battleships in port all fired at once to honor Abraham Lincoln. At noon the Gettysburg Address was read in the public schools across America. The culmination of the 100th anniversary was the minting of the first coin bearing the image of an American president, the Lincoln penny. Lately, it seems like the only talk we hear about the penny come from those who want to abolish it. But there may be more to that little copper coin than meets the eye. Well, copper depending on what year you’re talking about. If your Lincoln penny has a date before 1982, it is made of 95% copper. If it is dated 1983 or later, it is made of 97.5% zinc and plated with a thin copper coating.

Since that auspicious debut in 1909, probably no other object in human history has been reproduced more often: to date 1.65 trillion times and counting my friends. That is 1,650,000,000,000 in case you wonder what it looks like. The US Mint estimates 200,035,318,672 are currently in circulation. So what happened to the other 1.4 trillion pennies? Lost in couches? Under car seats? Buried in back yards? My father-in-law Keith Hudson once told me that if you have a stubborn tree stump in the backyard that you want gone just stick a copper penny in it. Well, I don’t know about that but it sure does get you thinking. Maybe that explains where all those pennies went.

Regardless, the U.S. Mint still produces more than 13 billion pennies annually. That’s approximately 30 million pennies per day; 1,040 pennies every second. More than two-thirds of all coins produced by the U.S. Mint are pennies and the U.S. Government estimates that $62 million in circulated pennies are lost every year (according to Bloomberg). In fact, the penny is the most widely used denomination in circulation and it remains profitable to make. Each penny costs .93 of a cent to make, but the Mint collects one cent for it. The profit goes to help fund the operation of the Mint and to help pay the public debt. The average penny lasts 25 years.

Regardless, the U.S. Mint still produces more than 13 billion pennies annually. That’s approximately 30 million pennies per day; 1,040 pennies every second. More than two-thirds of all coins produced by the U.S. Mint are pennies and the U.S. Government estimates that $62 million in circulated pennies are lost every year (according to Bloomberg). In fact, the penny is the most widely used denomination in circulation and it remains profitable to make. Each penny costs .93 of a cent to make, but the Mint collects one cent for it. The profit goes to help fund the operation of the Mint and to help pay the public debt. The average penny lasts 25 years.

The penny was the very first coin minted in the United States. In March 1793, the mint distributed 11,178 copper cents. During its early penny-making years, the U.S. Mint was so short on copper that it accepted copper utensils, nails and scrap from the public to melt down for the coins. That 1909 Lincoln centennial penny was the first U.S. coin to feature a historic figure and the first to have the motto “IN GOD WE TRUST”. Lincoln faces to the right, while all other portraits on coins face to the left. To date, there have been 11 different designs featured on the penny.

Legend claims that we owe that Lincoln penny to Teddy Roosevelt. Privately, President Theodore Roosevelt told intimates that American coins were “pedestrian and uninspiring”. In July 1908, he sat several times for Victor David Brenner, a Lithuanian-born Jew who, since coming to the United States 19 years earlier, had become one of the nation’s premier medalists. Lincoln, like most immigrants, was Brenner’s personal hero. He was the first American he learned about from his tenement house on New York’s Lower East Side. During those White House sittings, Brenner showed Roosevelt a bas-relief sculpture of Lincoln based on a Mathew Brady photograph. Roosevelt, a great admirer of Lincoln himself, allegedly decreed that Brenner’s Lincoln must go on a new penny to commemorate Lincoln’s 100th birthday in 1909.

Putting Lincoln on the most widely circulated coin made perfect sense, after all, it was Lincoln who’d said “Common-looking people are the best in the world; that is the reason the Lord makes so many of them.” Brenner received $1,000 for the commission. Production of the Lincoln penny began at the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia on July 10, 1909. The sculptor asked that he receive the first 100 of the new Lincoln pennies, but his request was deinied, so great was the anticipation. Fearing regional jealousies, the Mint ordered the coin be released across the country simultaneously. That May, the Boston Globe reported, “The new Lincoln cents, it seems, will be distributed the first week in August…It is so hard to wait!”

On Monday, Aug. 2, 1909 the New York Sun reported on the first of the new Lincoln pennies issued by the Federal Sub-treasury (today’s Federal Reserve Bank) to long lines of budding numismatists waiting anxiously in the financial district. “The big man down in Wall Street yesterday was the man who had a few of the new Lincoln cents. He could have had a fairly good time on 10 of them; he could start a celebration on a quarter’s worth, and for 50 of them there was no reason why he couldn’t purchase a regular jubilee.” The lines continued all week long and by Friday, even the rain couldn’t dampen the money rush in Lower Manhattan.

Some people near the front of the lines sold their spots for a dollar. Other more ambitious entrepreneurs hired women, who in a still chivalrous era, were ushered to the head of the line. “Within 15 minutes there were enough girls at the door to make it look like a bargain counter sale on a busy Monday,” The Sun reported. Many in what The Tribune called “the penny-mad crowd” were poor raged looking little children, some carrying a single battered Indian Head penny to trade in. The resale rate hovered around three new pennies for a nickel, but shot up slightly when supplies ran low. It was pretty much the same all around the country.

The Washington Star compared the “penny-chasers” to the crowds watching the Wright brothers test their new “aeroplanes.” The Boston Globe said, “you could get the new Lincoln coins for a cent apiece by spending, say, a dollar’s worth of time.” The Illinois State Register in Lincoln’s Springfield hometown reported that the Lincoln Bank ordered 5,000, but received only 50. Even in the old Confederacy, The Constitution newspaper reported that “demand was so high outside one Atlanta bank the crowd would have made a Chicago bread line look small.”

Carl Sandburg wrote, “If it were possible to talk with that great, good man, he would probably say that he is perfectly willing that his face is to be placed on the cheapest and most common coin in the country. Follow the travels of the penny and you find it stops at many cottages and few mansions. … The common, homely face of ‘Honest Abe’ will look good on the penny, the coin of the common folk from whom he came and to whom he belongs.”

The ALPLM’s “problems” began back in 2007 when it purchased the famous Taper collection for $23 million. “The collection is amazing,” says Sam, “the Lincoln top hat and bloodied gloves seem to be the items that resonate most with people, but the collection is much more than that.” Dr. Wheeler says that the uniqueness of the Taper collection centers around its emphasis on assassination related items, a field that had been largely ignored by Lincoln collectors at that time of its assemblage. The collection was created by Louise Taper, daughter-in-law of Southern California real estate magnate S. Mark Taper. She created the exhibition The Last Best Hope of Earth: Abraham Lincoln and the Promise of America which was at the Huntington Library from 1993–1994 and at the Chicago Historical Society from 1996-1997.

The ALPLM’s “problems” began back in 2007 when it purchased the famous Taper collection for $23 million. “The collection is amazing,” says Sam, “the Lincoln top hat and bloodied gloves seem to be the items that resonate most with people, but the collection is much more than that.” Dr. Wheeler says that the uniqueness of the Taper collection centers around its emphasis on assassination related items, a field that had been largely ignored by Lincoln collectors at that time of its assemblage. The collection was created by Louise Taper, daughter-in-law of Southern California real estate magnate S. Mark Taper. She created the exhibition The Last Best Hope of Earth: Abraham Lincoln and the Promise of America which was at the Huntington Library from 1993–1994 and at the Chicago Historical Society from 1996-1997. “Bottom line,” Sam says, “we need to keep the collection here. That is our first priority.” It is easy to see how important this collection is to Dr. Wheeler by simply watching his eyes as he speaks. To Wheeler, the collection is not just a part of the museum, it is a part of the state of Illinois. Sam relates how when he speaks to groups, which he does quite regularly on behalf of the ALPLM, he often reaches into the vault to bring along pieces from the Taper collection to fit the topic. “People love seeing these items. It gives them a direct connection to Lincoln.” states Wheeler.

“Bottom line,” Sam says, “we need to keep the collection here. That is our first priority.” It is easy to see how important this collection is to Dr. Wheeler by simply watching his eyes as he speaks. To Wheeler, the collection is not just a part of the museum, it is a part of the state of Illinois. Sam relates how when he speaks to groups, which he does quite regularly on behalf of the ALPLM, he often reaches into the vault to bring along pieces from the Taper collection to fit the topic. “People love seeing these items. It gives them a direct connection to Lincoln.” states Wheeler. Hoosiers may ask, why doesn’t the ALPLM just ask the state of Illinois for the money? After all, with 300,000 visitors annually, the Lincoln Library Museum is one of the most popular tourist sites in the state of Illinois and is prominently featured in all of their state tourism ads. Well, the state is billions of dollars in debt despite approving a major income-tax increase last summer and as of the time of this writing, has yet to put together a budget. To the casual observer, one would think that financial stalemate between the state and the museum would be a no-brainer when you consider that the ALPLM has drawn more than 4 million visitors since opening in 2005. The truth is a little more complicated than that. Illinois State government runs and funds the Lincoln library and museum. The separately run foundation raises private funds to support the presidential complex. The foundation, which is not funded by the state, operates a gift store and restaurant but has little role in the complex’s operations, programs and oversight.

Hoosiers may ask, why doesn’t the ALPLM just ask the state of Illinois for the money? After all, with 300,000 visitors annually, the Lincoln Library Museum is one of the most popular tourist sites in the state of Illinois and is prominently featured in all of their state tourism ads. Well, the state is billions of dollars in debt despite approving a major income-tax increase last summer and as of the time of this writing, has yet to put together a budget. To the casual observer, one would think that financial stalemate between the state and the museum would be a no-brainer when you consider that the ALPLM has drawn more than 4 million visitors since opening in 2005. The truth is a little more complicated than that. Illinois State government runs and funds the Lincoln library and museum. The separately run foundation raises private funds to support the presidential complex. The foundation, which is not funded by the state, operates a gift store and restaurant but has little role in the complex’s operations, programs and oversight.

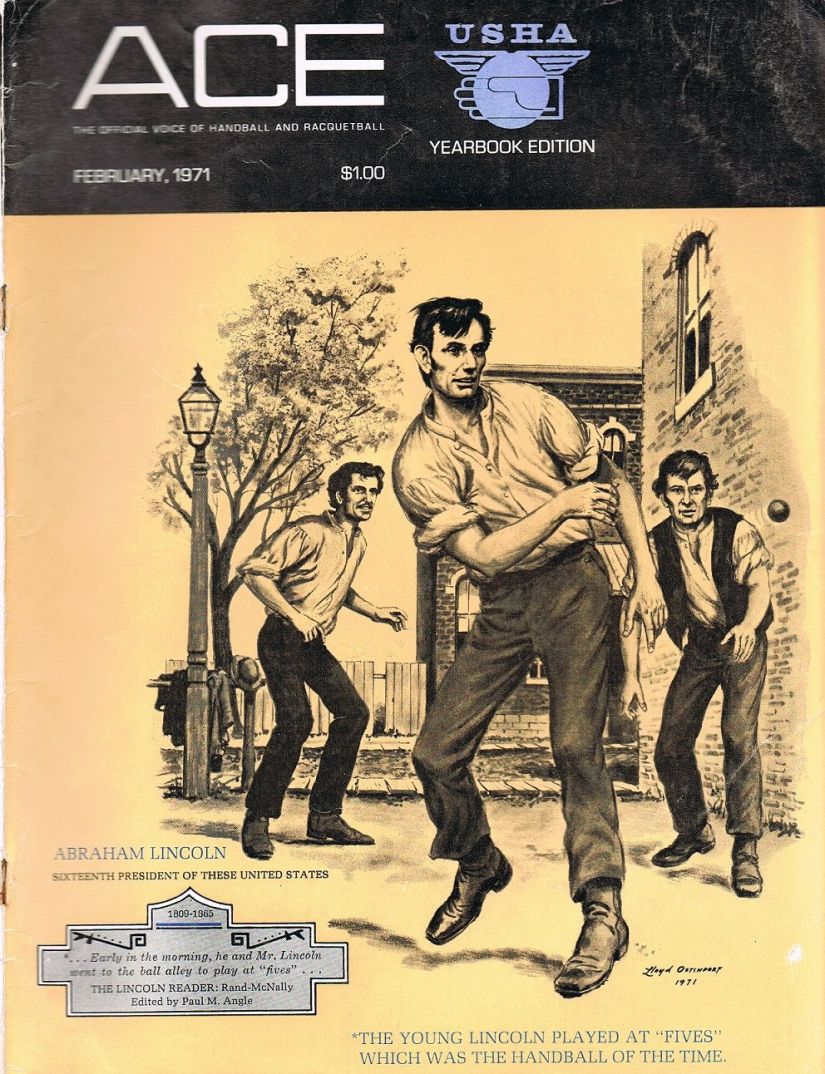

Likewise, you may have heard that he was a handball player, as have I, but details have always been hard to find. The game of handball was much better suited to Lincoln. At 6 feet 4 inches tall, his long legs and gangly arms served the rail splitter well. Muscles honed while wielding an axe as a youth were kept tight and toned as an adult. Lincoln milked his own cows and chopped his own wood even though he was a successful, affluent lawyer with little time to spare.

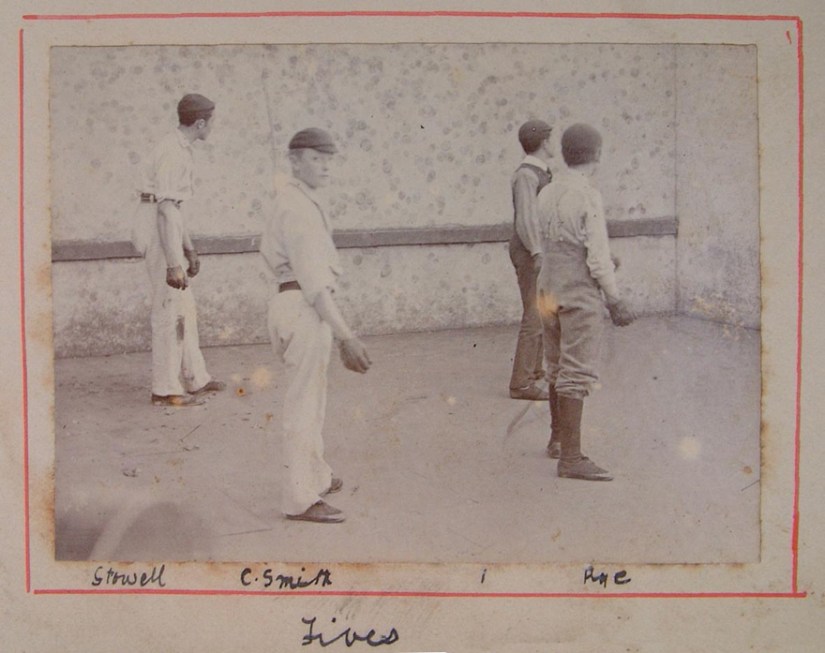

Likewise, you may have heard that he was a handball player, as have I, but details have always been hard to find. The game of handball was much better suited to Lincoln. At 6 feet 4 inches tall, his long legs and gangly arms served the rail splitter well. Muscles honed while wielding an axe as a youth were kept tight and toned as an adult. Lincoln milked his own cows and chopped his own wood even though he was a successful, affluent lawyer with little time to spare. The term handball really didn’t exist in Lincoln’s day. It was called a “game of fives” by Abe and his contemporaries. When Mr. Lincoln went to town, he frequently joined with the boys in playing handball. In the Springfield version, players choose sides to square off against one another. The game is begun by one of the boys bouncing the ball against the wall of the Logan building. As it bounced back, and opponent strikes it in the same manner, so that the ball is kept going back and forth against the wall until someone misses the rebound. ‘Old Abe’ was often the winner, for his long arms and long legs served a good purpose in reaching and returning the ball from any angle his adversary could send it to the wall. The game required two, four or six players, spread equally on each side. The three players who lost paid 10 ¢ each, making 30 ¢ a game. So as you can imagine the games got pretty serious.

The term handball really didn’t exist in Lincoln’s day. It was called a “game of fives” by Abe and his contemporaries. When Mr. Lincoln went to town, he frequently joined with the boys in playing handball. In the Springfield version, players choose sides to square off against one another. The game is begun by one of the boys bouncing the ball against the wall of the Logan building. As it bounced back, and opponent strikes it in the same manner, so that the ball is kept going back and forth against the wall until someone misses the rebound. ‘Old Abe’ was often the winner, for his long arms and long legs served a good purpose in reaching and returning the ball from any angle his adversary could send it to the wall. The game required two, four or six players, spread equally on each side. The three players who lost paid 10 ¢ each, making 30 ¢ a game. So as you can imagine the games got pretty serious. Court clerk Thomas W.S. Kidd spoke of Mr. Lincoln’s love of the game: “In 1859, Zimri A. Enos, Esq., Hon. Chas. A. Keyes, E. L. Baker, Esq., then editor of the Journal, William A. Turney, Esq., Clerk of the Supreme Court, and a number of others, in connection with Mr. Lincoln, had the lot, then an open one, lying between what was known as the United States Court Building, on the northeast corner of the public square, and the building owned by our old friend, Mr. John Carmody, on the alley north of it, on Sixth street, enclosed with a high board fence, leaving a dead wall at either end. In this ‘alley’ could be found Mr. Lincoln, with the gentlemen named and others, as vigorously engaged in the sport as though life depended upon it. He would play until nearly exhausted and then take a seat on the rough board benches arranged along the sides for the accommodation of friends and the tired players.”

Court clerk Thomas W.S. Kidd spoke of Mr. Lincoln’s love of the game: “In 1859, Zimri A. Enos, Esq., Hon. Chas. A. Keyes, E. L. Baker, Esq., then editor of the Journal, William A. Turney, Esq., Clerk of the Supreme Court, and a number of others, in connection with Mr. Lincoln, had the lot, then an open one, lying between what was known as the United States Court Building, on the northeast corner of the public square, and the building owned by our old friend, Mr. John Carmody, on the alley north of it, on Sixth street, enclosed with a high board fence, leaving a dead wall at either end. In this ‘alley’ could be found Mr. Lincoln, with the gentlemen named and others, as vigorously engaged in the sport as though life depended upon it. He would play until nearly exhausted and then take a seat on the rough board benches arranged along the sides for the accommodation of friends and the tired players.” Lincoln’s friend, Dr. Preston H Bailhache, recalled a handball game played on a court built by Patrick Stanley in an ‘alley’ in the rear of his grocery in the Second Ward, which is still standing. “I have sat and laughed many happy hours away watching a game of ball between Lincoln on one side and Hon. Chas. A. Keyes on the other. Mr. Keyes is quite a short man, but muscular, wiry and active as a cat, while his now more distinguished antagonist, as all now know, was tall and a little awkward, but which with much practice and skill in the movement of the ball, together with his good judgment, gave him the greatest advantage. In a very hotly contested game, when both sides were ‘up a stump’ – a term used by the players to indicate an even game – and while the contestants were vigorously watching every movement, Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Turney collided with such force that it came very near preventing his nomination to the Presidency, and giving to Springfield a sensation by his death and burial. Both were badly hurt, but not so badly as to discourage either from being found in the ‘alley’ the next day.”

Lincoln’s friend, Dr. Preston H Bailhache, recalled a handball game played on a court built by Patrick Stanley in an ‘alley’ in the rear of his grocery in the Second Ward, which is still standing. “I have sat and laughed many happy hours away watching a game of ball between Lincoln on one side and Hon. Chas. A. Keyes on the other. Mr. Keyes is quite a short man, but muscular, wiry and active as a cat, while his now more distinguished antagonist, as all now know, was tall and a little awkward, but which with much practice and skill in the movement of the ball, together with his good judgment, gave him the greatest advantage. In a very hotly contested game, when both sides were ‘up a stump’ – a term used by the players to indicate an even game – and while the contestants were vigorously watching every movement, Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Turney collided with such force that it came very near preventing his nomination to the Presidency, and giving to Springfield a sensation by his death and burial. Both were badly hurt, but not so badly as to discourage either from being found in the ‘alley’ the next day.” Another eyewitness was the unofficial gatekeeper of the Handball Court, William Donnelly, a nephew of John Carmody. Years later, Donnelly offered this account to a reporter, “I worked in the Carmody store and usually had charge of the ball court. I smoothed the wall and leveled the ground. I made the balls. Old stockings were rolled out and wound into balls and covered with buckskin. Mr. Lincoln was not a good player. He learned the game when he was too old. But he liked to play and did tolerably well. I remember when he was nominated as though it were yesterday. It was the last day of the convention and he was plainly nervous and restless.”

Another eyewitness was the unofficial gatekeeper of the Handball Court, William Donnelly, a nephew of John Carmody. Years later, Donnelly offered this account to a reporter, “I worked in the Carmody store and usually had charge of the ball court. I smoothed the wall and leveled the ground. I made the balls. Old stockings were rolled out and wound into balls and covered with buckskin. Mr. Lincoln was not a good player. He learned the game when he was too old. But he liked to play and did tolerably well. I remember when he was nominated as though it were yesterday. It was the last day of the convention and he was plainly nervous and restless.” John Carmody recalled another handball game: “An incident took place, during one of those games, which I have retained clearly in my memory. I had a nephew named Patrick Johnson who was very expert in the game. He struck the ball in such a manner that it hit Mr. Lincoln in the ear. I ran to sympathize with him and asked if he was hurt. He said he was not, and as he said it he reached both of his hands toward the sky. Straining my neck to look up into his face, for he was several inches taller than I was, I said to him, ‘Lincoln, if you are going to heaven, take us both.’”

John Carmody recalled another handball game: “An incident took place, during one of those games, which I have retained clearly in my memory. I had a nephew named Patrick Johnson who was very expert in the game. He struck the ball in such a manner that it hit Mr. Lincoln in the ear. I ran to sympathize with him and asked if he was hurt. He said he was not, and as he said it he reached both of his hands toward the sky. Straining my neck to look up into his face, for he was several inches taller than I was, I said to him, ‘Lincoln, if you are going to heaven, take us both.’” In October of 2004, the Smithsonian Institution displayed Abraham Lincoln’s handball as part of their exhibit “Sports: Breaking Records, Breaking Barriers.” It’s small (about the size of a tennis ball), dirty and well worn and really, really old. The ball has “No. 2” stamped on the side but it is unclear if the stamp was on the ball when Lincoln handled it or if it was stamped on the side for reference years later. It came from the Lincoln Home in Springfield, where Lincoln lived with his family from 1844 until 1861.

In October of 2004, the Smithsonian Institution displayed Abraham Lincoln’s handball as part of their exhibit “Sports: Breaking Records, Breaking Barriers.” It’s small (about the size of a tennis ball), dirty and well worn and really, really old. The ball has “No. 2” stamped on the side but it is unclear if the stamp was on the ball when Lincoln handled it or if it was stamped on the side for reference years later. It came from the Lincoln Home in Springfield, where Lincoln lived with his family from 1844 until 1861. Although Assassin John Wilkes Booth was not in the production, he would appear at the McVicker’s 4 times in different productions between 1862 & 1863 while Mr. Lincoln was in the White House. Ironically, the McVickers Theatre was the very first place where actor Harry Hawk began theater work as a call boy, or stagehand. Hawk was the actor on stage alone at the moment of Lincoln’s assassination and likely uttered the last words Mr. Lincoln ever heard. Who knew a well worn piece of leather sports equipment could have so many connections?

Although Assassin John Wilkes Booth was not in the production, he would appear at the McVicker’s 4 times in different productions between 1862 & 1863 while Mr. Lincoln was in the White House. Ironically, the McVickers Theatre was the very first place where actor Harry Hawk began theater work as a call boy, or stagehand. Hawk was the actor on stage alone at the moment of Lincoln’s assassination and likely uttered the last words Mr. Lincoln ever heard. Who knew a well worn piece of leather sports equipment could have so many connections?

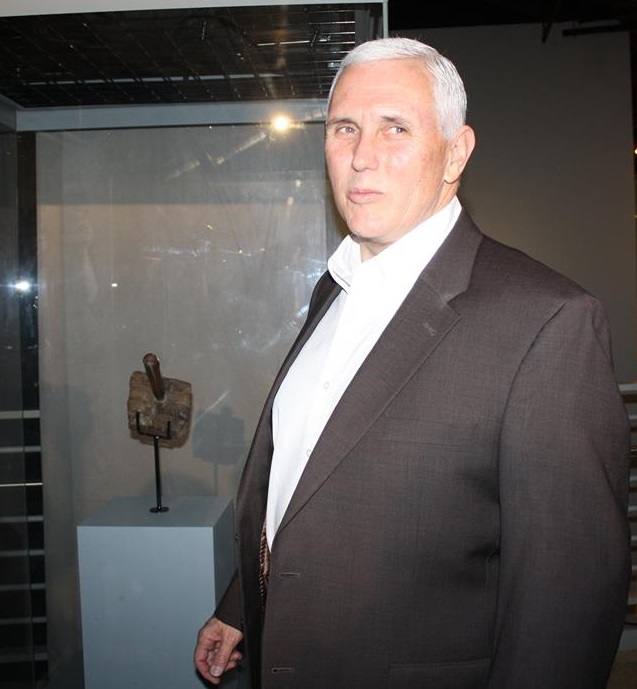

The primitive looking hammer seems perfectly matched to the muscular 20-year-old young man who wielded it back in 1829. The mallet is made from the trunk of a tree cut from the virgin timber forest that once populated Spencer County, Indiana. No doubt Thomas Lincoln cut the tree from the unbroken forest surrounding the family cabin for use by his young son Abraham in splitting wood. Those famous “rail splitting” images we all remember from our history books? Well they all picture Honest Abe using this mallet.

The primitive looking hammer seems perfectly matched to the muscular 20-year-old young man who wielded it back in 1829. The mallet is made from the trunk of a tree cut from the virgin timber forest that once populated Spencer County, Indiana. No doubt Thomas Lincoln cut the tree from the unbroken forest surrounding the family cabin for use by his young son Abraham in splitting wood. Those famous “rail splitting” images we all remember from our history books? Well they all picture Honest Abe using this mallet. Before Governor Pence dropped the curtain to reveal the relic, he took off his jacket to reveal rolled up shirt sleeves in a workingman’s fashion to honor the Indiana Railsplitter. “I thought it was appropriate for the occasion,” the Governor explained. Staying in the moment, Pence harkens back to a predecessor by repeating Governor Otis Bowen’s quote, “Lincoln made Illinois, but Indiana made Lincoln.” He made sure to mention his trip to Southern Indiana a couple days before to bury another predecessor, Edgar Whitcomb, who died February 6th. Make no mistake about it, Mike Pence loves Indiana history.

Before Governor Pence dropped the curtain to reveal the relic, he took off his jacket to reveal rolled up shirt sleeves in a workingman’s fashion to honor the Indiana Railsplitter. “I thought it was appropriate for the occasion,” the Governor explained. Staying in the moment, Pence harkens back to a predecessor by repeating Governor Otis Bowen’s quote, “Lincoln made Illinois, but Indiana made Lincoln.” He made sure to mention his trip to Southern Indiana a couple days before to bury another predecessor, Edgar Whitcomb, who died February 6th. Make no mistake about it, Mike Pence loves Indiana history.

The mallet most closely resembles a carnival strongman’s prop,or Thor’s hammer, but a closer examination immediately reveals it’s cryptic secret. Above the handle’s stem lay the initials “A.L.” with a year date of “1829.” Steve Haaff explains that the initials and date are not carved as one may surmise, but rather they are metal inlays. Haaff states, “Thomas Lincoln was a carpenter and Abe was his only apprentice. Thomas hoped that his young son would follow him into carpentry, but Abe Lincoln wanted to be a blacksmith. These metal pieces were inserted into the mallet by Abe Lincoln himself.”

The mallet most closely resembles a carnival strongman’s prop,or Thor’s hammer, but a closer examination immediately reveals it’s cryptic secret. Above the handle’s stem lay the initials “A.L.” with a year date of “1829.” Steve Haaff explains that the initials and date are not carved as one may surmise, but rather they are metal inlays. Haaff states, “Thomas Lincoln was a carpenter and Abe was his only apprentice. Thomas hoped that his young son would follow him into carpentry, but Abe Lincoln wanted to be a blacksmith. These metal pieces were inserted into the mallet by Abe Lincoln himself.” ISM’s Ogden further explains, “He didn’t put those initials and that date into the mallet because he was Abraham Lincoln, he put them there to mark the tool as his own. He was just a Hoosier farm-boy at the time with no idea he was on his way to becoming a legend.” Ogden, whose fervor for Lincoln is rivaled by few, explains the mallet’s secret by identifying it as the only known item that ties Abraham Lincoln to Indiana. “The Lincoln’s were Indiana pioneers, they arrived here just a week before we were made a state in the Union. While they were not poor, they were also not wealthy.” says Ogden. “The Lincoln family used everything they owned, in most cases using it all up. When they moved to Illinois in 1830, they couldn’t take everything with them and this mallet was among those things left behind. Whether Abe gave the mallet to his neighbors, or whether the Carter family simply picked it up from the pile of discards is debatable. But we’re certainly glad it survived and are delighted to be able to display it for our guests.”

ISM’s Ogden further explains, “He didn’t put those initials and that date into the mallet because he was Abraham Lincoln, he put them there to mark the tool as his own. He was just a Hoosier farm-boy at the time with no idea he was on his way to becoming a legend.” Ogden, whose fervor for Lincoln is rivaled by few, explains the mallet’s secret by identifying it as the only known item that ties Abraham Lincoln to Indiana. “The Lincoln’s were Indiana pioneers, they arrived here just a week before we were made a state in the Union. While they were not poor, they were also not wealthy.” says Ogden. “The Lincoln family used everything they owned, in most cases using it all up. When they moved to Illinois in 1830, they couldn’t take everything with them and this mallet was among those things left behind. Whether Abe gave the mallet to his neighbors, or whether the Carter family simply picked it up from the pile of discards is debatable. But we’re certainly glad it survived and are delighted to be able to display it for our guests.” Ogden explains that the ISM was fortunate to obtain the collection and although it is vast and comprehensive, he says that the question he got the most from visitors was, “Where is the Indiana material? and I always had to reply, There is no Indiana material. This mallet changes all that. Those railsplitter legends were all we had. This mallet confirms that folklore and brings all of those stories together.”

Ogden explains that the ISM was fortunate to obtain the collection and although it is vast and comprehensive, he says that the question he got the most from visitors was, “Where is the Indiana material? and I always had to reply, There is no Indiana material. This mallet changes all that. Those railsplitter legends were all we had. This mallet confirms that folklore and brings all of those stories together.” Lincoln’s mother Nancy died of milk sickness in October of 1818. Haaff states that the planks were made from a log from the leftovers pile used to make the family cabin. “Thomas made the coffin while 9-year-old Abe sat nearby and whittled the pegs for his mother’s coffin.” His mother’s death, and that of his beloved elder sister Sarah’s death 10 years later, devastated Lincoln and laid the foundation for the depression that haunted him for the rest of his life. No doubt, Thomas and Abraham made the coffin for Sarah too.

Lincoln’s mother Nancy died of milk sickness in October of 1818. Haaff states that the planks were made from a log from the leftovers pile used to make the family cabin. “Thomas made the coffin while 9-year-old Abe sat nearby and whittled the pegs for his mother’s coffin.” His mother’s death, and that of his beloved elder sister Sarah’s death 10 years later, devastated Lincoln and laid the foundation for the depression that haunted him for the rest of his life. No doubt, Thomas and Abraham made the coffin for Sarah too.