Here is the radio show companion to my March 13th & 20th and June 19, 2025 articles in the Weekly View newspaper, all of which are available to read on this site.

Here is the radio show companion to my March 13th & 20th and June 19, 2025 articles in the Weekly View newspaper, all of which are available to read on this site.

Original publish date June 19, 2025.

https://weeklyview.net/2025/06/19/nazi-ideology-on-the-eastside-a-contnuance/

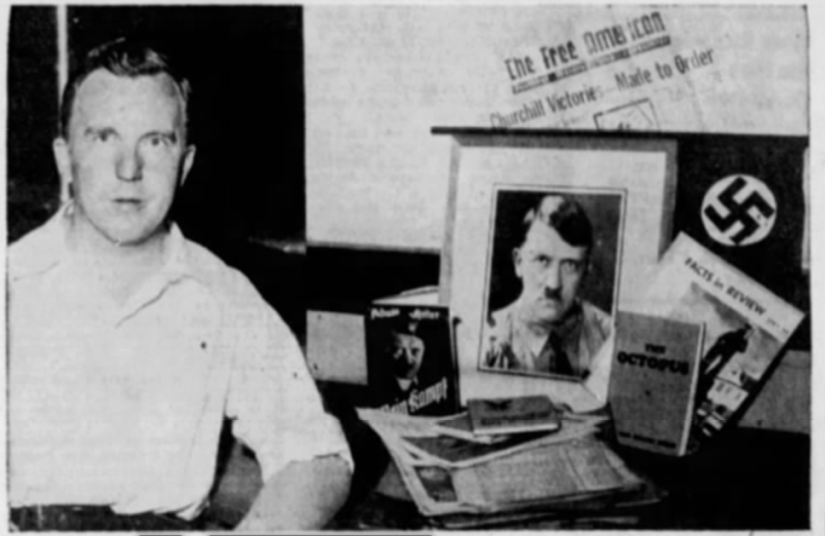

Last March, I wrote a two-part article on Eastsider Charles Soltau, the “Nazi at Arsenal Tech”. This Saturday (June 21st) at noon, I will revisit those articles on Nelson Price’s “Hoosier History Live” radio show WICR 88.7 FM. Nelson, a longtime friend of Irvington, has a personal connection to that story, which he will share for the first time ever during that broadcast. As it happens, weeks after that article appeared, quite by accident, I ran across a few documents that spoke directly to that time in Indianapolis history.

While perusing a few boxes of vintage paper at a roadside antiques market, I found a pair of cards from February 1938, advertising one of the first 35 mm camera photo exhibitions in Indianapolis at the Hotel Lincoln. The Hotel Lincoln, built in 1918, was a triangular flat-iron building located on the corner of West Washington St. and Kentucky Ave. The hotel was named in honor of Abraham Lincoln, who made a speech from the balcony of the Bates House across the street in 1861. Afterwards, that block became known as “Lincoln Square.” The Hotel displayed a bust of Abraham Lincoln on a marble column in its lobby for decades. The Lincoln was a popular convention center and was once the tallest flat-iron building in the city. The Lincoln was the site of the arrest of musician Ray Charles (a subject covered in depth in one of my past columns). It also served as the headquarters for Robert Kennedy and his campaign staff, who leased the entire eleventh floor of the hotel during the 1968 Indiana primary. The Lincoln was intentionally imploded in April of 1973.

It was the Hotel Lincoln’s history that originally piqued my interest. The front of each card read, “You are invited to attend the Fourth International Leica Exhibit on display in the Hotel Lincoln, Parlor A, Mezzanine Floor, Indianapolis, Ind., from February 23 to 26 [1938], inclusive. Hours: 11 A.M. to 9 P.M. (on February 26, the exhibit will close at 5 P.M.) More than 200 outstanding Leica pictures will be on display, representing the use of the camera in various fields…Candid, Amateur, Commercial, Press and Scientific Photography. Do not fail to view this show which represents the progress in miniature camera photography throughout the year. Illustrated Leica Demonstration will be given at the American United Life Insurance Co., Auditorium, Indianapolis, February 24, 8:30 P.M. by Mrs. Anton F. Baumann. ADMISSION FREE. E. Leitz, Inc. New York, N.Y.” Research reveals that the winner of the contest was W.R. Henkel, who resided at 2936 E. Washington Street. Henkel received the Oscar Barnak Medal, named for the inventor of the Leica camera.

The Leica was the first practical 35 mm camera designed specifically to use standard 35 mm film. The first 35 mm film Leica prototypes were built by Oskar Barnack at Ernst Leitz Optische Werke, Wetzlar, in 1913. Some sources say the original Leica was intended as a compact camera for landscape photography, particularly during mountain hikes, but other sources indicate the camera was intended for test exposures with 35mm motion picture film. Leica was noteworthy for its progressive labor policies which encouraged the retention of skilled workers, many of whom were Jewish. Ernst Leitz II, who began managing the company in 1920, responded to the election of Hitler in 1933 by helping Jews to leave Germany, by “assigning” hundreds (many of whom were not actual employees) to overseas sales offices where they were helped to find jobs. The effort intensified after Kristallnacht in 1938, until the borders were closed in September 1939. The extent of what came to be known as the “Leica Freedom Train” only became public after his death, well after the war.

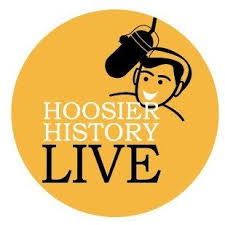

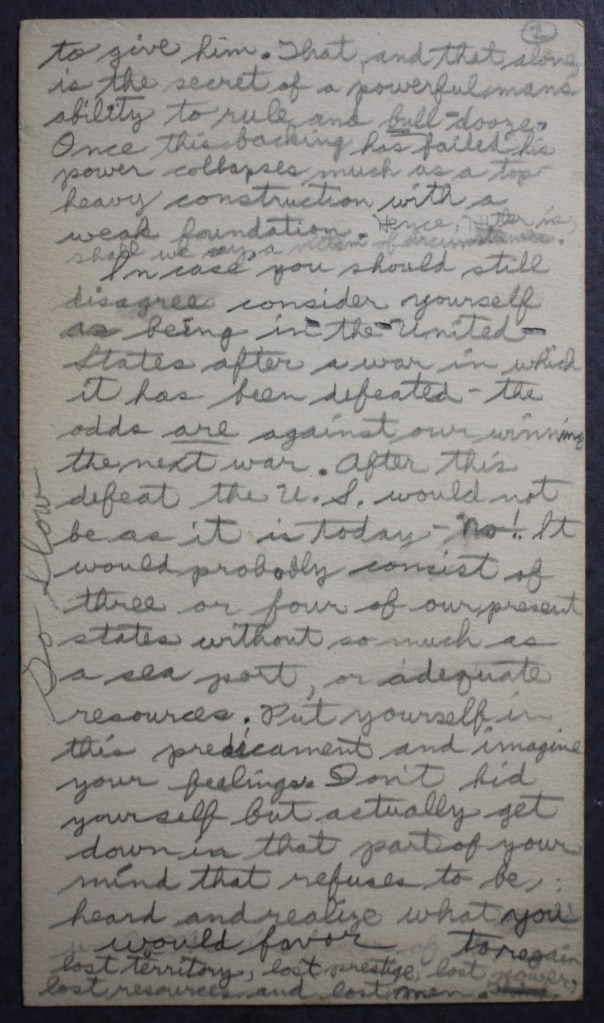

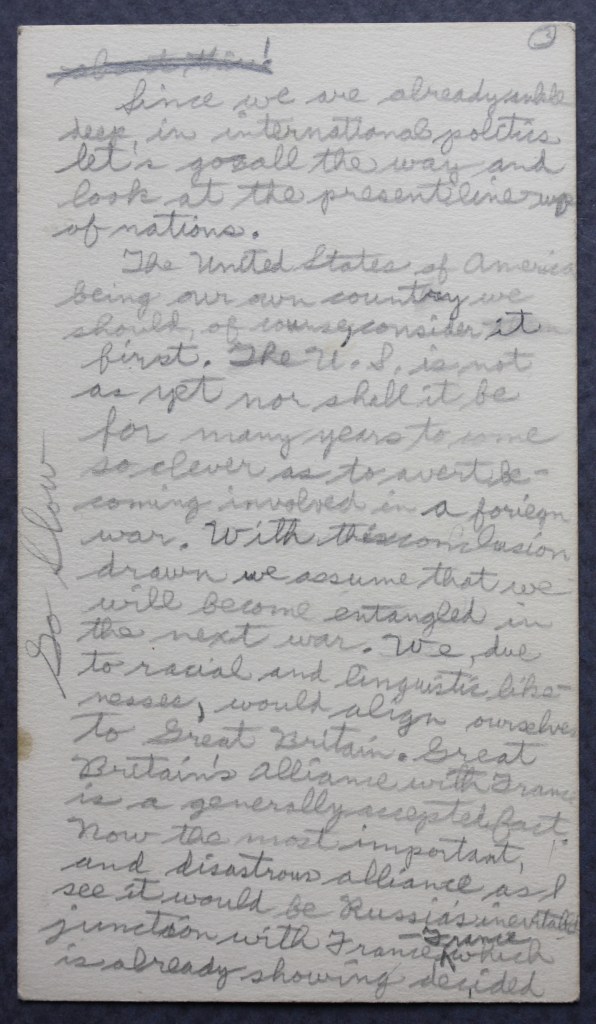

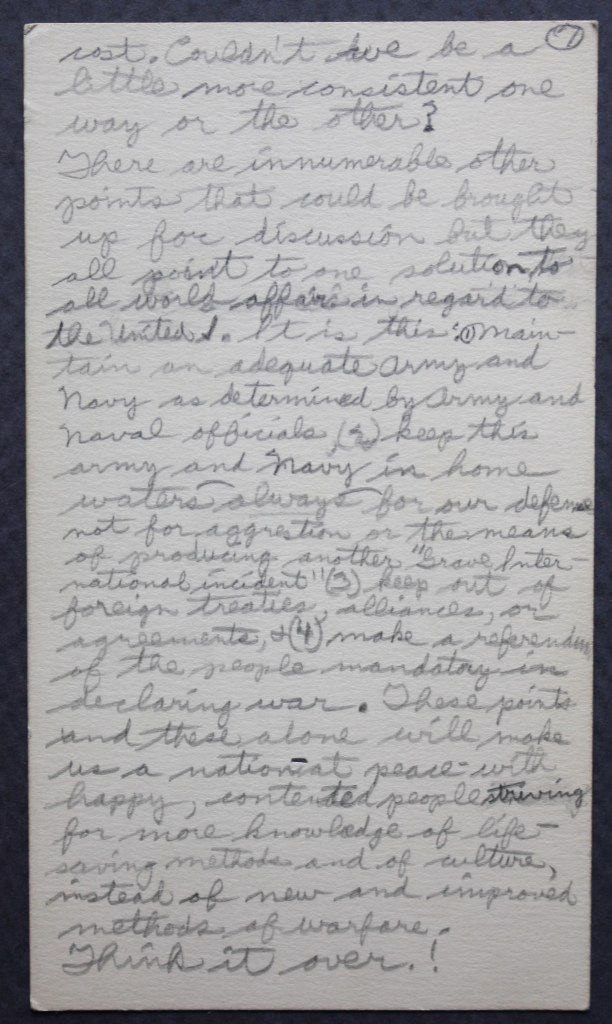

While my interest was drawn to the printed text, it was the handwritten pencil notations on the back of the cards that sparked that purchase. The cards contained a contemporary essay about the political atmosphere in the Circle City less than a month after the Soltau family’s Nazi incident. Written in pencil, the cards, numbered 1 and 2, read: “Hitler! Hitler Dictator of Germany! Is he to blame for the present aggressive stand of Deutchland? No! He is not. Directly, it is the German people that are to blame but additionally and more importantly, this aggressive attitude is the result of the great war to “make the world safe for Democracy!!” This is only a natural outcome of any war, whether large or small. After a war there is a spontaneous decline of morals. This is particularly evident on the defeated side because they have lost men, money, power, land, and consequently, resources. At the lowest ebb of a people’s hope they look to a leader, a strong, fearless, aggressive man. When this superman is found, the people raise him to great heights as their leader. One must remember that a dictator, or any other national leader, has only the power that his people are willing to give him. That, and that alone, is the secret of a powerful man’s ability to rule and bulldoze. Once the backing has failed, his power collapses much as a top-heavy construction with a weak foundation. Hence, Hitler is, shall we say, a victim of circumstance. In case you should still disagree, consider yourself as being in the United States after a war in which it has been defeated; the odds are against ever winning the next war. After this defeat the U.S. would not be as it is today. It would probably consist of three or four of our present states without so much as a seaport or adequate resources. Put yourself in this predicament and imagine your feelings. Don’t kid yourself but actually get down in that part of your mind that refuses to be heard and realize what you would favor to regain lost territory, lost prestige, lost power, lost resources, and lost men.”

The next week, I revisited that roadside market. Lo and behold, the same dealer was there, and he brought more boxes of paper. I found two more of those cards, numbered 3 & 7, with more of that essay featured on the reverse. “Since we are already ankle deep in international politics, let’s go all the way and look at the present lineup of nations. The United States of America, being our own country, we should, of course, consider it first. The U.S. is not as yet, nor shall it be for many years to come so clever as to ever become involved in a foreign war. With this conclusion drawn, we assume that we will become entangled in the next war. We, due to racial and linguistic likenesses, would align ourselves to Great Britain. Great Britain’s alliance with France ia a generally accepted fact . Now the most important and, disastrous as I see it, would be Russia’s inevitable junction with France, which is already showing decided…Couldn’t we be a little more consistent one way or the other?”

“There are innumerable other points that could be brought up for discussion, but they all point to one solution to all world affairs in regard to the United States. (1) It is this: maintain an adequate army and navy as determined by Army and Navy officials. (2) Keep this army and navy in home waters always for our defense and not aggression or the means of producing another “Grave international incident.” (3) Keep out of foreign treaties, alliances, or agreements. (4) Make a referendum of the people mandatory in declaring war. These points, and these alone, will make us a nation at peace with happy, interested people striving for more knowledge of lifesaving methods and of culture, instead of new and improved methods of warfare. Think it over!”

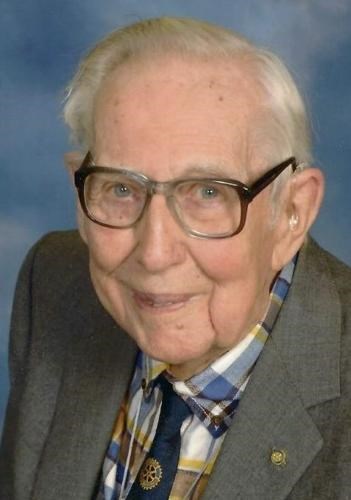

All four of these cards were authored (and signed) by Bob Shoemaker, Jr. of Anderson, IN. Robert W. Shoemaker, Jr. (1921-2022) Bob was born in New Philadelphia, Ohio, the only child of Robert W. Shoemaker, Sr. (1898-1968) and Irene English Shoemaker (1900-1988). The family moved to Anderson in 1935. Shortly after settling in Indiana, Bob became a Boy Scout. While attending the 1937 National Boy Scout Jamboree in Washington DC, Bob received his Eagle Scout award. It is likely that the seeds of this essay were planted when he sailed to Europe to participate in the 1937 World Jamboree in the Netherlands. Here, young Bobby Shoemaker witnessed the changes taking place in Hitler’s Germany firsthand. After graduating from Anderson High School in 1939, Bob enrolled in Harvard College and was on course to graduate with the Class of 1943 when the war came calling. Among Bob’s hobbies and interests were amateur radio, reading, history, and photography. Through slides, home movies, and videos, Bob compiled a remarkable visual history of his life and the life of his family from the 1920s to the current century. His many slides and movies taken during the 1937 Jamboree trips provide a fascinating glimpse of life in Washington DC, and Europe before the tragic onset of World War II. It was that love of photography that drew Bob to that Leica Exhibit at the Hotel Lincoln in Indianapolis back in 1938.

Bob was commissioned as an ensign in the U.S. Naval Reserve in 1942 and attended officers’ training programs in the Bronx, NY, and Washington, D.C, before being assigned to the Naval Mine Warfare Test Station at Solomons Island, MD, where he served as Naval personnel officer. After requesting a shipboard assignment, Bob was transferred to the Pacific for duty aboard the escort aircraft carrier U.S.S. Corregidor (CVE-58) as Lieutenant Junior Grade and Signal Officer until the ship’s decommissioning after the war in 1946. After World War II, Bob earned two graduate degrees from Harvard: an MBA and a Bachelor of Arts Degree in Government in 1947. Upon his return to Anderson in 1947, Bob remained active in the U.S. Naval Reserve Division 9-31. In 1949, Bob and his parents purchased Short Printing, Inc., then located on 20th Street near Fairview Street in Anderson. He successfully operated the business as President for almost five decades, which included building a larger one on Madison Avenue in 1961 and changing the name to Business Printing, Inc. He retired and sold the business in 2000. Bob was a Scoutmaster and Skipper of a Sea Scout ship in Anderson. He also held a variety of district and council leadership positions in Scouting for many years.

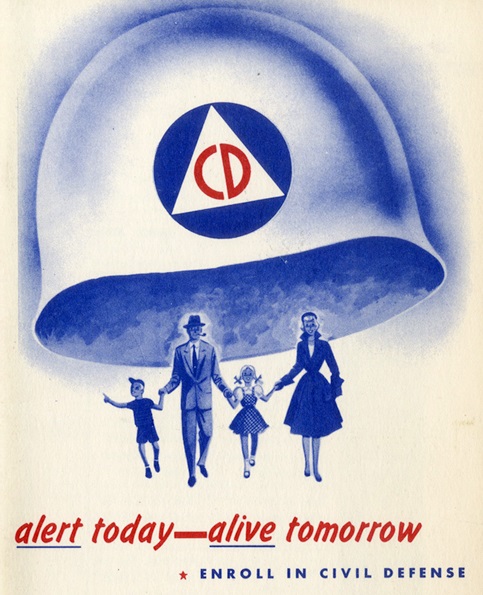

In 1946, Bob obtained his amateur radio license, and in 1952, he was asked to organize amateur radio communications for the Madison County Civil Defense, which led to his appointment as County Civil Defense Director, a position he held for 12 years. This period witnessed rising tensions with the Soviet Union and the threat of nuclear attacks, including the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. As CD Director, Bob gave many educational slide presentations regarding proper preparations in the face of nuclear threats, oversaw the selection and stocking of emergency fallout shelters throughout the county, and helped organize the conversion of the old Lindbergh School north of town into a CD emergency command headquarters. His slide show included photos taken in his capacity as an official observer at the Yucca Flats, Nevada, nuclear test in 1955. Later, Bob was invited by NASA to Cape Canaveral to observe the launch of Apollo 8, which carried astronauts into orbit around the moon for the first time, and the Apollo 15 moon mission launch. As a seven-decade member and officer of the Rotary Club, Bob secured NASA astronaut Al Worden, command module pilot for Apollo 15 and one of 24 people to have flown to the Moon, as a special speaker for the Madison County Rotary Club in 1971.

When Bob Anderson Jr.’s life is measured against that of his “peer,” Arsenal Tech grad Charles Soltau, it is easy to see that while both shared the same isolationist mentality as young men, one chose to follow that Nazi ideology of Adolf Hitler and the other followed that of Uncle Sam. Soltau faded into the obscurity that Gnaw Bone, Indiana, maintains to this day. Anderson became a public-spirited pillar of Madison County society whose shadow is still cast in that community — proving that idealogy comes and goes with the flow of generations. What often sounds like an attractive idea can easily morph into an unexpectedly bad outcome. Mark Twain is often quoted as having said, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes,” and, if so, it applies today.

I will be talking about this series of articles with Nelson Price on his radio show “Hoosier History Live” this Saturday June 21, 2025 noon to 1 (ET) on WICR 88.7 fm, or stream on phone at WICR HD1. See the link below.

Original publish date May 22, 2025.

https://weeklyview.net/2025/05/22/the-hilton-sisters-vaudevilles-beautiful-siamese-twins/

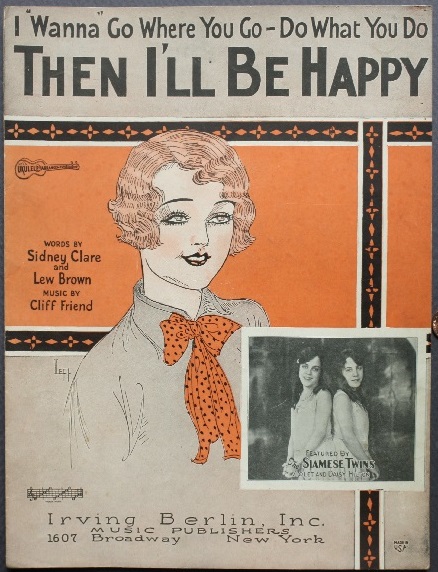

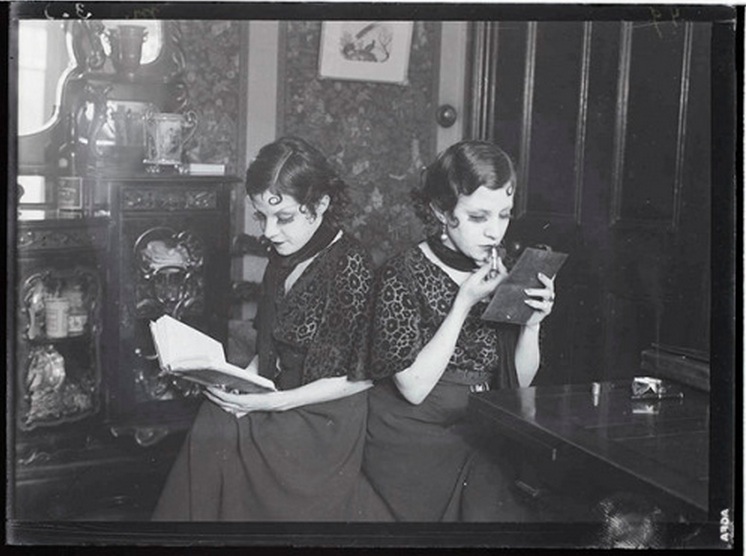

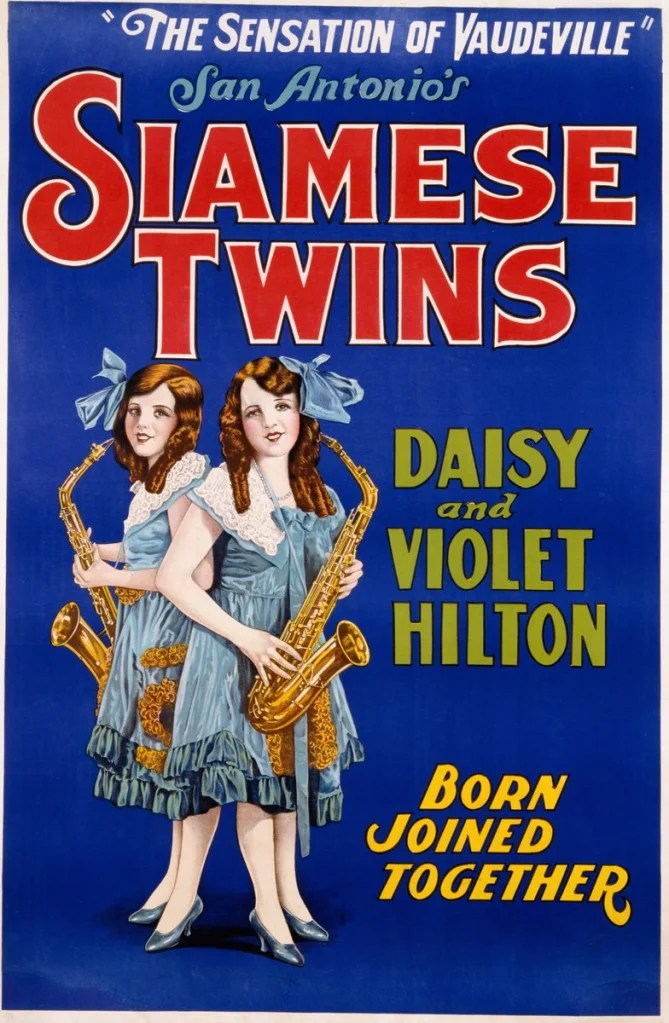

I recently ran across a five-dollar box of sheet music at an antique show. It seems like nobody wants sheet music anymore. I suppose, like recipe books, almanacs, TV guides, and car manuals, they are seen as obsolete nowadays. It turned out to be a fun, if not very valuable, box of paper. One was from the 1952 Marilyn Monroe film Niagara, along with a bunch of 1920s-40s songbooks and “how to” manuals for the Hawaiian guitar. The one that caught my eye was a piece of ukulele sheet music for the 1925 Irving Berlin song “I Wanna Go Where You Go—Do What You Do. Then I’ll Be Happy,” performed by a pair of lovely young ladies known as the “Hilton Sisters.” These beautiful young girls are pictured side by side on the cover in a pose that suggests that they were joined at the hip. A closer examination reveals a caption proclaiming the duo as a pair of conjoined “Siamese Twins,” and it turns out, during the Vaudeville era, Daisy and Violet Hilton were the biggest stars of their day.

Daisy and Violet Hilton were born on February 5, 1908, in Brighton, Sussex, England, birthplace of authors Charles Dickens and Rudyard Kipling. The twins were born to an unmarried barmaid named Kate Skinner. After seeing her babies, Kate was horrified, thinking that her children’s birth defects were a punishment from God for her unmarried status. She refused to look at them, let alone hold them, so she sold the girls to the midwife who had delivered them, Mary Hilton. Hilton looked at those baby girls and saw dollar signs. Hilton immediately began displaying the girls in the backroom of the Queen’s Arms pub on George Street, which she ran with her husband. As they grew, she taught the girls how to sing, dance, and play musical instruments. The Hilton sisters toured first in Britain in 1911 (aged three) as “The Double Bosses” and from then on, the twins were on the road touring the United Kingdom, Europe, and Australia. The twins were the first set of conjoined twins born in Britain to survive more than a few weeks. The girls were connected at the hip and pelvis by a fleshy appendage and shared no organs. Doctors stated that they could have easily been separated at an early age and would have lived independent lives. But the girls were seen as piggybanks in those formative years, so “fixing” them would kill the golden goose.

In 1913, rebranded as the “Famous Brighton United Twins”, they toured Australia, where they made their debut at Luna Park in Melbourne on Friday the 13th of December, 1912. Despite a massive advertising campaign, the novelty of their act quickly wore off. The show closed after only a week, and the twins, their mother Mary, and sister Edith were abandoned down under by the show’s promoter. Somewhere along the line, the Hilton family came into contact with Myer Myers, a traveling circus balloon and candy seller. Myers formed a romantic interest in the twins’ older sister Edith, and the couple was married. The marriage was not based on love, it was based on financial gain. While the twins were fond of their older sister, they never liked Myer.

In June 1916, Myer brought the girls to the United States via San Francisco. But immigration officials had never seen anything like Violet & Daisy before, so they were detained and quarantined at Angel Island (next to Alcatraz) in the San Francisco Bay for months until they were finally cleared for entry. By 1918, the 10-year-olds were traveling the Orpheum Circuit of Vaudeville Theatres across the country. The adorable little girls were extremely popular, although still categorized as medical oddities and relegated to the sideshow carnival “Freak Show” class. But the Hilton sisters were different, they weren’t just an act, they were talented. The girls were trained in singing and dancing and eventually learned to play the piano, violin, and saxophone. The twins made huge amounts of money in Vaudeville, but regardless of who was managing them, they retained very little of it.

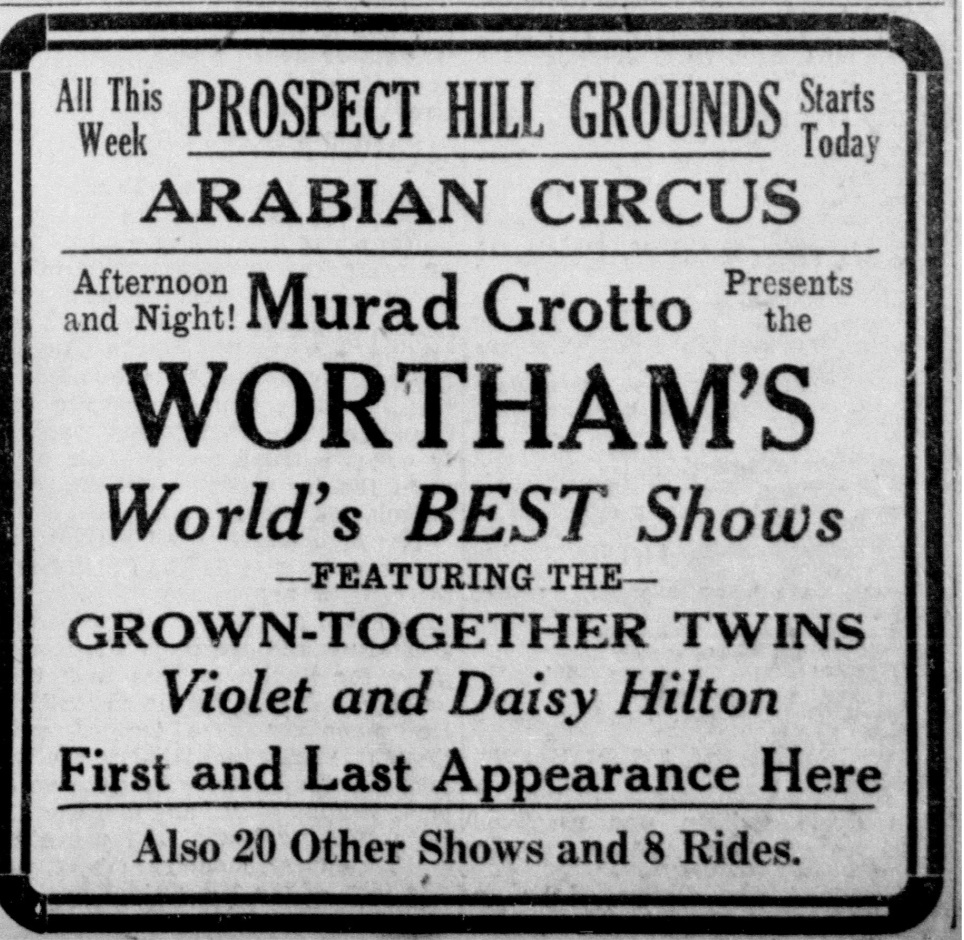

Throughout their lives, Violet and Daisy often voiced their dislike of Myer Myers and how he exerted complete control over every aspect of their lives. Myers insisted that the twins call him “Sir,” that the girls sleep in the same bedroom with their parents, and when they were not performing in the circus, that they spend their days doing school lessons and practicing their musical instruments. The twins were also forbidden to play with other children. Myer Myers promoted the twins unscrupulously and toured them mercilessly. In time, the twins became the star attraction of the “Great Wortham Show”, a traveling carnival that toured the United States. People around the country flocked to see these beautiful, mysterious young girls. In 1917, while performing at the San Jacinto Fiesta in San Antonio, Myers built a castle-like pavilion directly across from the Alamo. Now, every visitor to the shrine of Texas independence made the trip across the street to see the twins. Myers continued to tour the twins across the USA, and whenever he entered a city or town, he ensured that the first stop was a visit to the mayor or, if it was a state capital, the governor.

The Hilton Sisters exploded onto the American scene at precisely the right time, for the years between World War I and World War II were considered the heyday of vaudeville side shows. On stage, the adorable twin girls sang, danced, and played saxophone & piano. They were exhibited as children as sideshow curiosities, but now they toured the United States in vaudeville theatres and American burlesque circuits in the 1920s and 1930s. Myers reinvented the twins’ biographies, saying their “Mother died at their birth and their father, a soldier, was killed a short time afterward in an accident. Firmly joined together at the base of their spines, the Hilton girls present a curious spectacle, especially so as the odd grafting of nature has materialized into a seemingly uncomfortable back-to-back, half-diagonal position. Despite this, the girls move about with an ease and freedom and movement that is nothing less than astonishing.”

The Indianapolis News for Saturday, March 28, 1925, touted the twins’ first appearance at the Globe Theatre, reporting that the performance got out of hand. Their appearance caused traffic jams, and police were called to control the lines of rowdy curiosity seekers on the streets outside trying to get into the theater. During their act, the girls sang songs, played music, and always concluded in the same fashion: a waltz. Two young men were waiting in the wings offstage. On cue, the men would glide out and dance with the sisters in rythm to an orchestra posed behind them. One of those young men was an unknown vaudevillian named Lester Townsend, soon to be known to the world as Bob Hope. In 1926, the sisters teamed up with up-and-coming comedian Bob Hope, who formed a new vaudeville act he called “Dancemedians.”

The twins appeared onstage with other luminaries like George Burns & his wife Gracie Allen, Sophie Tucker, and Charlie Chaplin. The Twins’ songwriter during their vaudeville years was Bart Howard (then known as Howard Joseph Gustafson), who wrote “Fly Me To The Moon.” That same Star newspaper article reported that the girls were like any other pair of sisters. Sometimes they would fight, and one sister would not speak to the other for days offstage. The article noted that the “girl’s fingerprints were different, one would read while the other slept, one sister may prick her finger, but the other is unaware of it, but,if one has a headache, the other will feel it. Daisy sews, but Violet is not particularly fond of sewing. Daisy enjoys housework while Violet prefers to arrange the furniture and decorate the house. There seemed to be a subtle telepathy between the twins.”

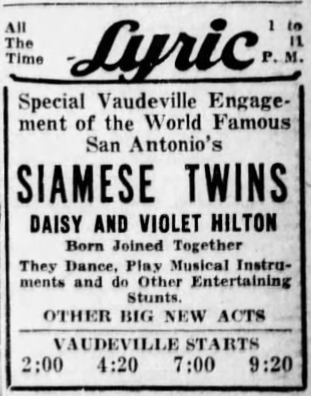

Throughout the 1920s, the twins earned $5,000 per week for 44 weeks on the Orpheum Circuit, over $91,000 weekly in today’s money. They were the highest-paid vaudeville act in America. Myer Myers was their manager, and the girls never saw a dime of that money. The Hilton Sisters were befriended by escapologist Harry Houdini, who taught them how to “mentally separate from each other.” Learning of the twins’ disadvantageous financial arrangement with Myer Myers, Houdini strongly advised the girls to emancipate themselves from their legal guardians and hit the road on their own. In his book Very Special People, author Frederick Drimmer quoted Houdini as telling the twins, “You must learn to forget your physical link. Put it out of your mind. Work at developing mental independence from each other.” Houdini died on Halloween night of 1926 and was never able to help the twins achieve that goal in his lifetime. The girls appeared in Indianapolis many times during their career. Indianapolis had a strong vaudeville, burlesque, and theatre district. The Hilton Sisters appeared at the Lyric Theatre on March 6, 1928, and again on September 6, 1928. Before that appearance, Chicago Commissioner of Health Herman Bundersen declared them healthy and described them as: “Two souls with but a single thought.” While the girls received a clean bill of health, both physically and spiritually, could the same be said of their industry?

PART II

The Hilton Sisters-Vaudeville’s Beautiful Siamese Twins.

Original publish date May 29, 2025.

https://weeklyview.net/2025/05/29/the-hilton-sisters-vaudevilles-beautiful-siamese-twins-part-2/

In the Roaring Twenties, the Hilton Sisters were the darlings of Vaudeville. That circuit ran straight through the heart of Indianapolis. Violet and Daisy Hilton were conjoined twins who were abandoned by a single mother and sold to a Brighton, Sussex, England, saloon matron who subjected them to years of exploitation, only to be adopted by a corrupt manager on the fringes of the sideshow circus & show-business circuits. Despite those obstacles, the twins managed to strike out on their own and become hugely successful stars of stage, vaudeville, and film in the United States.

These personal appearances would most often last for a week or more. Since the Hilton Sisters traveled 52 weeks a year, wherever they laid their suitcase was their home. Five years after his death, their mentor Harry Houdini’s wish for the sisters was realized. The Indianapolis Times of Saturday, April 25, 1931, reported “Verdict Frees Siamese Twins From Bondage. Texas Pair Wins $99,000 in ruling releasing them from Guardian.” The sensational trial made headlines all over the country. After the verdict, the girls told reporters, “It is so wonderful to be free to go wherever we please, choose our own friends, and appear in public as humans rather than as freaks.” However, even though the twins received a boatload of money (over $1.8 million in today’s world), the rigid structure of Myer Myers disappeared, and the girls ran through that money in a relatively short time.

The twins, now aged 24, appeared in the 1932 exploitation movie “Freaks”, which led to another promotonal appearance at the Lyric theatre in Indianapolis (June to July 1932). The Indianapolis Times of July 31, 1932, reported: “The Hilton Sisters, Siamese Twins, were seen going into a subway station recently and a crowd of nearly one hundred people followed them to see if they would pay one fare or two. They paid two.” “We may seem like one, but everything costs us for two,” Daisy explained. “We pay insurance for two, but could only collect for one. The only bargain we get is our weight for a penny.” (For the record, the twins stood four feet six inches tall and weighed 166 pounds, or 83 pounds each.)

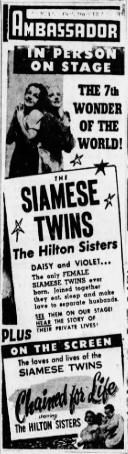

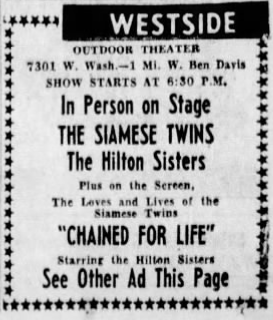

The twins came back to the Circle City in May to June 1936, at the “Chez Paree nightclub downstairs at the Apollo Theatre”, Dec 22-28, 1946, at the “Murat Theatre”, March 26, 1947 at the “Fox Burlesk Theatre”, and from May to June, 1952 at the “Ambassador Theatre.” These appearances all coincided with the slow downward spiral of the Hilton Sisters’ career. The first talkie movie (Al Jolson’s The Jazz Singer on Oct. 27, 1927) signaled the end of the Vaudeville Era.

During those years, as Great Depression Era America watched these unique beauties mature to adulthood, the Hilton Sisters remained in the news. The twins resumed their vaudeville careers as “The Hilton Sisters’ Revue”. Daisy dyed her hair blonde, and they began to wear different outfits to distinguish each other. After vaudeville lost popularity, the sisters performed at burlesque venues. But Burlesque reviews were risque, and while the attending patrons were interested in women, they were not necessarily interested in women wearing clothing, talented or not.

After gaining independence from Myer Myers, the Hiltons sailed to the UK, where they spent most of 1933, returning to the States in October 1933. Violet began a relationship with musician Maurice Lambert, and they applied in 21 states for a marriage license, but were always refused. The Indianapolis Star Fri, Jul 06, 1934, reported on the prospect of marriage: “The very idea is quite immoral and indecent. No, there is no law against it, but it just seems indecent.” Maurice grew tired of the newsreel life and one day, simply walked away from the relationship. Afterward, Violet became briefly engaged to Jewish boxer Harry Mason, who later went on to have a relationship with Daisy. In 1936, Violet married actor James Moore at the Cotton Bowl during the Texas Centennial Exposition as a publicity stunt. The marriage lasted ten years on paper, but the couple never lived as husband and wife. It was discovered that Jim Moore was gay, so the marriage was eventually annulled.

At the time of Violet’s wedding, the press noted that Daisy was visibly pregnant. Daisy gave birth, but the child, a boy, was put up for adoption immediately. In 1941, Daisy married Harold Estep, better known as dancer Buddy Sawyer. The marriage lasted ten days when it was discovered that Buddy, like Violet’s husband Jim Moore, was gay.

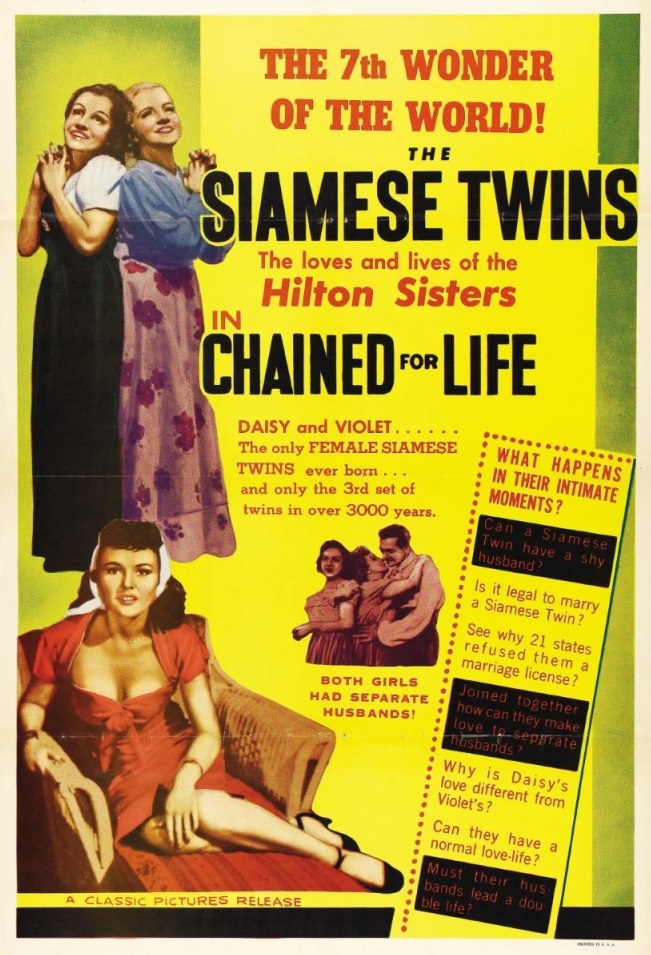

In 1952, the twins starred in a second film, Chained for Life, an exploitation film loosely based on their lives. The film’s producer ran off with all the money and left the Hilton Sisters holding the bag. They paid the bills out of their own pockets and undertook a grueling series of personal appearances at double-bill screenings of their two films in theatres and drive-ins across the country. Sadly, the entertainment world had moved on, and few people were interested in the aging vaudevillians, curiously conjoined or not. Afterwards, their popularity faded, and they struggled to make a living in show business. Violet once told a reporter, ‘We fooled ourselves that by entertaining others we were making ourselves happy.’

The Hiltons’ last public appearance was in 1961 at a drive-in theater in Charlotte, North Carolina. Without warning, their tour manager abandoned them there with no means of transportation or income. Charles Reid, owner of the Park-N-Shop grocery store in Charlotte, hired the twins for a commercial advertising “Twin-pack” potato chips. Afterward, they applied for a job at the store, stating they would work for one salary if necessary. Reid, ever the savvy businessman, realized he was getting four hands on one body and hired them as produce handlers and checkout girls. He paid them each a salary. The twins worked at a specially designed and constructed checkout station that looked no different than the others. The only way anyone would know the difference was if they looked back over their shoulder as they walked out the door.

The Hiltons rented a small two-bedroom home courtesy of Purcell United Methodist and settled into a quiet life centered around work and church. Daisy learned how to drive a car because she was the twin who could sit in the left-hand driver’s seat. Later, the twins bought a former driving instructor’s car with dual controls, so Violet could also drive.

Violet and Daisy had very different political views: Violet was a staunch Democrat, while Daisy supported the Republican Party. During the holidays, they remembered fellow employees and favorite customers with small, inexpensive Christmas gifts. One neighbor recalled that the girls had a phone booth installed in the home to allow for private conversations for each twin when needed and that the twins kept an array of purses around the house, each one containing two or three dollars for cab fare. Later in life, a doctor visited them and declared that they could be separated if they so desired, but they said no. Daisy contracted Hong Kong flu, but Violet refused medical intervention.

On January 4, 1969, after failing to report to work and unable to reach them by telephone, the store manager called the police to investigate. The twins were found dead in their home, victims of the Hong Kong flu. Their bodies were found on the heat grate in the hallway. Daisy’s decomposition was worse than Violet’s, which presents a nightmare scenario. The autopsy determined that Daisy died first and Violet died two to four days later. It was speculated that during those final few days, freezing cold from the Hong Kong flu, Violet dragged her sister to the heat grate and slumped to the floor where she drank heavily and chain-smoked cigarettes while waiting for the end to come. The house was adorned by carefully wrapped Christmas presents, all identified and tagged to go to their friends. They had spent every second of their lives together and had made a pact that they were going out together.

The Hilton Sisters were buried together in one casket in a donated plot at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Charlotte, NC. At their funeral service, the Reverend Jon Sills said, as he stood next to the sisters’ wide coffin: “Daisy and Violet Hilton were in show business for all but the last half dozen years of their life. In the end, though, they were cast aside by the glittery and glamorous world they had been part of for so long. In the end, it was only ordinary people who showed they cared about them.”

In May 2018, it was announced that Brighton and Hove City Council in Sussex, England, and the current owner of the house in which the twins were born had agreed that a commemorative plaque could be erected at the property. On May 26, 2022, a commemorative blue plaque was unveiled at 18 Riley Road, dedicated to them. Additionally, the Brighton & Hove Bus and Coach Co. honored the twins by naming a bus after them. Upon their death in 1969, Mrs. Luther E. Mason, a longtime friend of the twins and secretary to the lawyer who represented them at their trial, said that they wanted nothing more than to “live normally.”

Original publish date May 15, 2025.

https://weeklyview.net/2025/05/15/foul-ball/

Last week, I ran a story about Cleveland Indians phenom Bob Feller’s pitched foul ball that hit and injured his mother during a game against the White Sox at old Comiskey Park in Chicago. That got me thinking about other foul ball stories and legends I’d heard about. Growing up, I spent a lot of time at old Bush Stadium on 16th Street in Indy. My dad, Robert Eugene Hunter, a 1954 Arsenal Tech grad, had worked there as a kid selling Cracker Jack/popcorn in the stands during the Victory Field years. He recalled with pleasure seeing Babe Ruth in person there and could name his favorites from those great Pittsburgh Pirates farm club teams from the late 1940s/early 1950s. I can’t tell you how many RCA Nights at Bush Stadium he took me to back in the 1970s during the team’s affiliation with the Cincinnati Reds Big Red Machine. During those outings, nothing was more exciting than chasing foul balls.

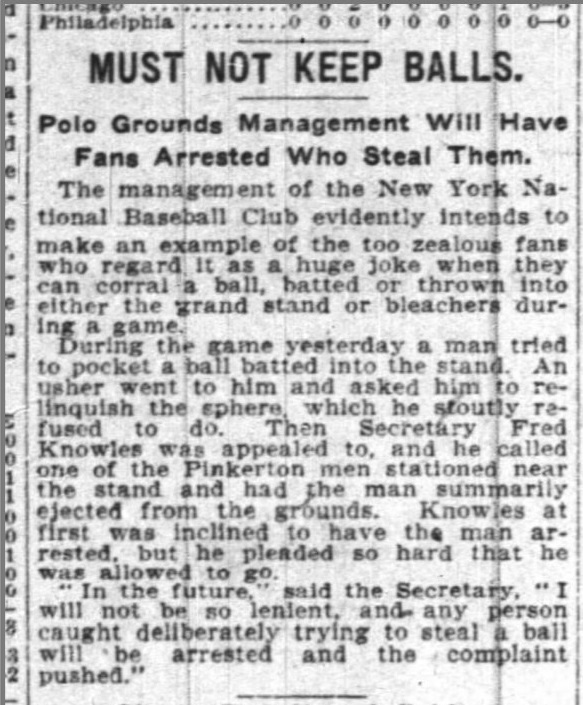

Not all foul balls are fun adventures, though; some are crazy, and others are just plain scary. Growing up, I loved reading about the exploits of those players who played before World War I. Back in those days, baseballs were considered team property and quite expensive. Fans were expected to return any ball hit into the stands (including homeruns), and balls hit out of the stadium were meticulously retrieved. In 1901, the National League rules committee, as a way of cutting costs, suggested fining batters for excessively fouling off pitches. Beginning in 1904, per a newly created league rule, teams posted employees in the stands whose sole job was to retrieve foul balls caught by the fans. Fans had a keen sense of humor, though, and they would often hide them from the “goons” or frustrate the hapless employees by throwing them from row to row. Sometimes, the games of keep-away in the stands were more fun to watch than the ones on the field. But those early WWI stories mostly involved the exploits of the players, not the fans. There were some characters in the league back then. Some of them are long forgotten and some made the Baseball Hall of Fame.

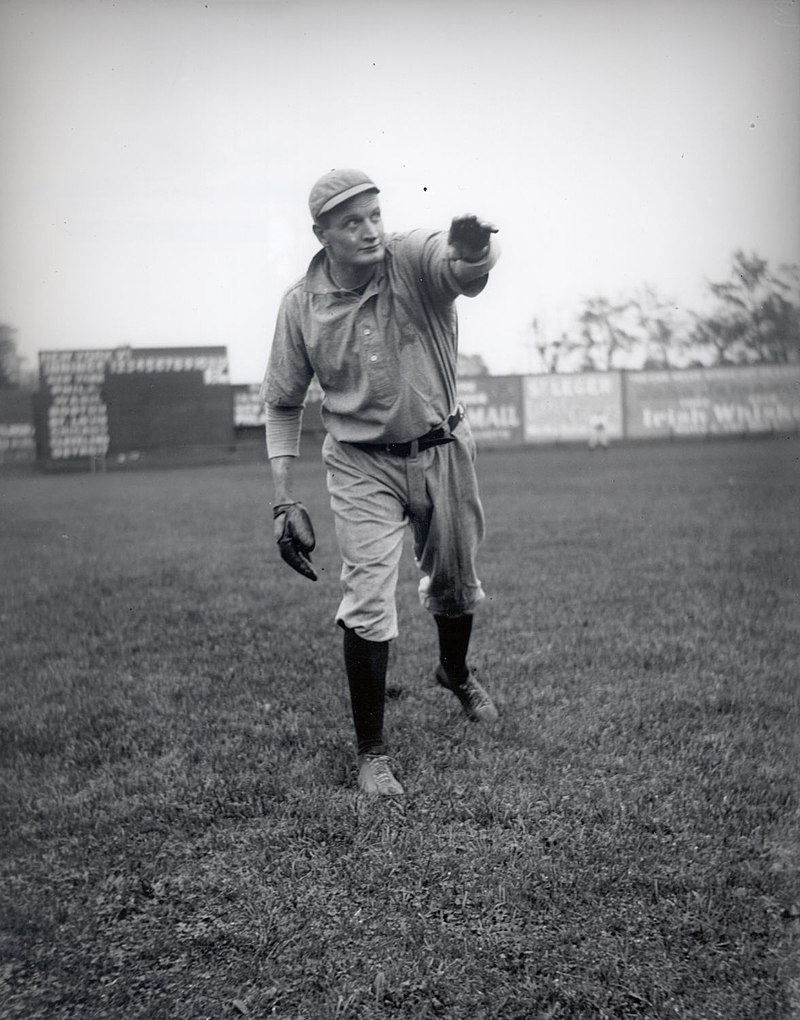

One of my favorite players from that hardball era was a square-jawed eccentric left-handed pitcher from the oil town of Bradford, Pa. named George Edward “Rube” Waddell (1876-1914). Rube played for 5 teams in 13 years. His lifetime 193-143 record, 2,316 strikeouts, and 2.16 ERA landed him in the Hall of Fame. And if there were a hall of fame for flakes in baseball, Rube would have been a first-ballot electee. If a plane flew above the field, Rube would stop in the middle of a game. If Rube heard the siren of a firetruck, he’d drop his glove and chase it. He once left in the middle of a game to go fishing. Opposing fans knew that Rube was easily distracted so they brought puppies to the game and held them up in the stands to throw him off. Rival teams brought puppies into the dugout for the same reason, knowing that Rube would drop his glove and run over to play with them every time. Shiny objects seemed to put Rube in a trance. His eccentric behavior led to constant battles with his managers and scuffles with bad-tempered teammates. Even though he was a standout pitcher, Rube’s foulball stories came off his bat, not out of his hand.

On August 11, 1903, the Philadelphia Athletics were visiting the Red Sox. In the seventh inning, Rube Waddell was at the plate. Waddell lifted a foul ball over the right field bleachers that landed on the roof of a Boston baked bean cannery next door. The ball rolled to a stop and became wedged in the factory’s steam whistle, which caused it to go off. It wasn’t quitting time yet, but the workers abandoned their posts, thinking it was an emergency. The employee exodus caused a giant caldron full of beans to boil over and explode. Suddenly, the ballpark was showered by scalding hot beans. Nine days before, on August 2, another foul ball off the bat of Waddell hit a spectator, supposedly igniting a box of matches in the fan’s pocket and ultimately setting the poor guy’s suit on fire and causing an uproar.

Waddell’s 1903 E107 Card.

Still, a foul ball hit by the aptly named George Burns of the Tigers in 1915 is worth mentioning in the same breath. His “scorching” foul liner struck an unlucky fan in the area of his chest pocket, where he was carrying a box of matches. The ball ignited the matches, and a soda vendor had to come to the rescue, dousing the flaming fan with bubbly to put out the fire.

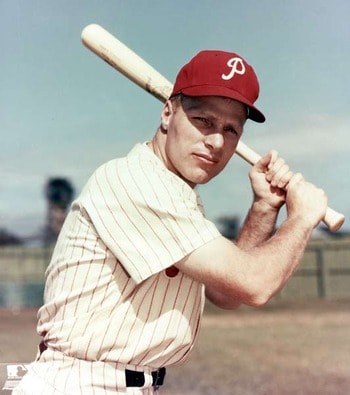

Richie Ashburn figures in many of the best foul ball stories in baseball lore. A contact hitter, Ashburn had the ability to foul off many consecutive pitches till he found one he liked. On one occasion, he fouled off fourteen consecutive pitches against Corky Valentine of the Reds. Another time, he victimized Sal “The Barber” Maglie for “18 or 19″ fouls in one at-bat. ”After a while,” said Ashburn, “he just started laughing. That was the only time I ever saw Maglie laugh on a baseball field.” Ashburn’s bat control was such that one day he asked teammates to pinpoint a particularly offensive heckler seated five or six rows back. The next time up, Ashburn nailed the fan in the chest. On another occasion, Ashburn unintentionally injured a female fan who was the wife of a Philadelphia newspaper sports editor. Play stopped as she was given medical aid. Action resumed as the stretcher wheeled her down the main concourse, and, unbelievably, Ashburn’s next foul hit her again. Thankfully, she escaped with minor injuries.

Another notable foul ball hitter was Luke Appling, the Hall of Fame shortstop with a career batting average of .310. As the story goes, Appling once asked White Sox management for a couple of dozen baseballs, so he could autograph them and donate them to charity. Management balked, citing a cost of several dollars per baseball. Appling bought the balls from his team, then went out that day and fouled off a couple dozen balls, after which he tipped his hat toward the owner’s box. He never had to pay for charity balls again, the legend goes.

Another great foul ball story involves Pepper Martin and Joe Medwick of the St. Louis Cardinals famous Gas House Gang teams of the mid-1930s. With Martin at bat, Medwick took off from first base, intending to take third on the hit-and-run. Martin fouled the ball into the stands, and Reds catcher Gilly Campbell reflexively reached back to home plate umpire Ziggy Sears for a new ball. Then, just for fun, Campbell launched the ball down to third, where Sears, forgetting that a foul had just been hit and that he had given Campbell a new ball, called Medwick out. The Cardinals were furious, but not wanting to admit his error, Sears refused to reverse his call, and Medwick was thrown out-on a foul ball!

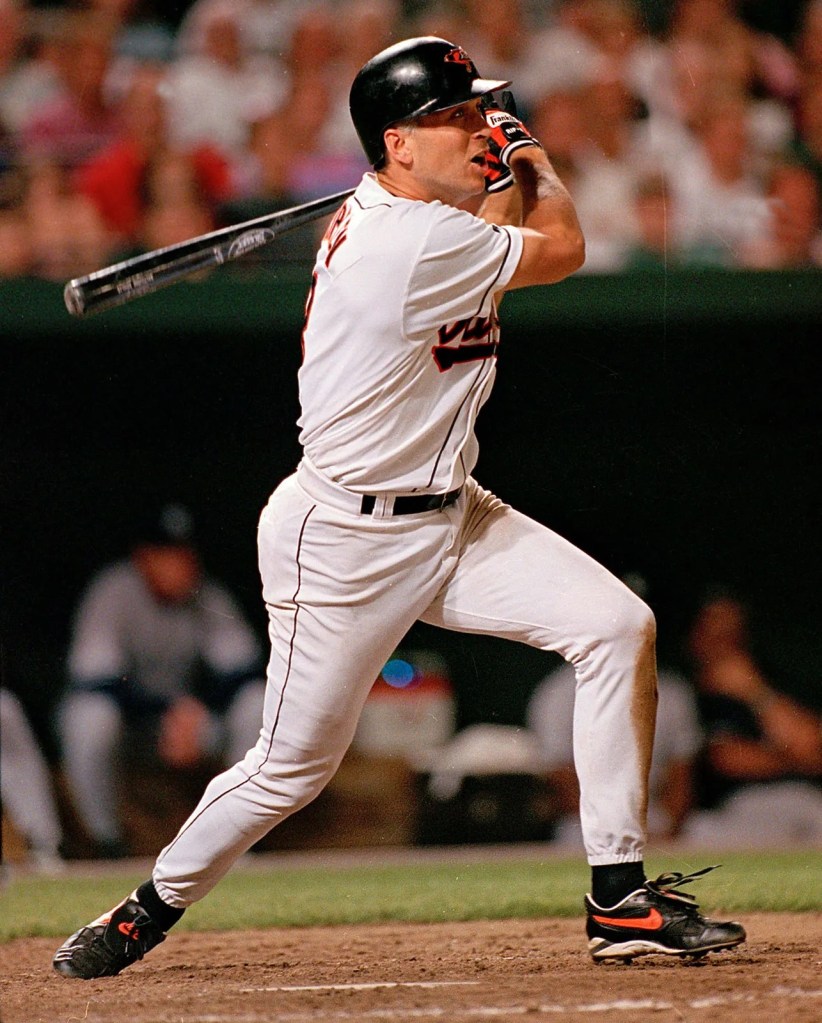

The great Cal Ripken Jr. made life imitate art with a foul ball in 1998. In the movie The Natural, Roy Hobbs lofts a foul ball at sportswriter Max Mercy, as Mercy sits in the stands drawing a critical cartoon of the slumping Hobbs. Baltimore Sun columnist Ken Rosenthal faced a similar wrath of the baseball gods after he wrote a column in 1998 suggesting that it might be time for Ripken to voluntarily end his streak, at that point several hundred games beyond Lou Gehrig’s old record, for the good of the team. Ripken responded by hitting a foul ball into the press box, which smashed Rosenthal’s laptop computer, ending its career. When told of his foul ball’s trajectory, Ripken responded with one word: “Sweet.”

Another sweet story involves a father and son combination. In 1999, Bill Donovan was watching his son Todd play center field for the Idaho Falls Braves of the Pioneer League. Todd made a nice diving catch and threw the ball back into the second baseman, who returned it to the pitcher. On the next pitch, a foul ball sailed into the outstretched hands of the elder Donovan. “I was like a kid when I caught it,” said the proud papa. “It made me wonder when was the last time that a father and son caught the same ball on consecutive pitches.”

One day in 1921, New York Giants fan Reuben Berman had the good fortune to catch a foul ball, or so he thought. When the ushers arrived moments later to retrieve the ball, Reuben refused to give it up, instead tossing it several rows back to another group of fans. The angered usher removed Berman from his seat, took him to the Giants’ offices, and verbally chastised him before depositing him in the street outside the Polo Grounds. An angry and humiliated Berman sued the Giants for mental and physical distress and won, leading the Giants, and eventually other teams, to change their policy of demanding foul balls be returned. The decision has come to be known as “Reuben’s Rule.”

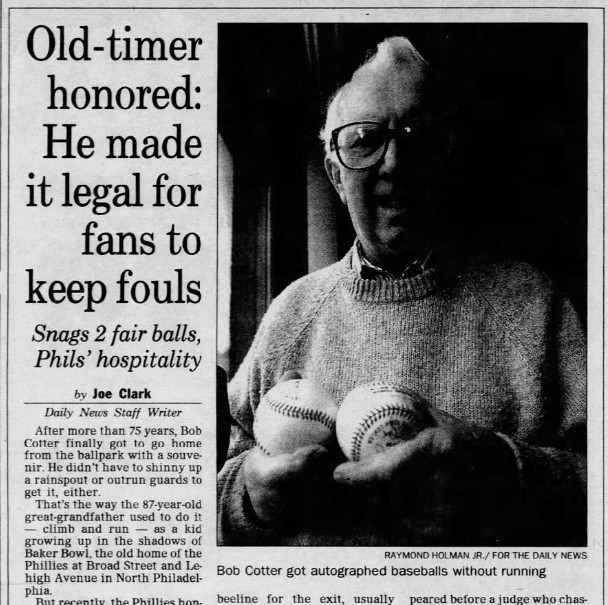

While Berman’s case was influential, the influence had not spread as far as Philadelphia by 1922, when 11-year-old fan Robert Cotter was nabbed by security guards after refusing to return a foul ball at a Phillies game. The guards turned him over to police, who put the little tyke in jail overnight. When he faced a judge the next day, young Cotter was granted his freedom, the judge ruling, “Such an act on the part of a boy is merely proof that he is following his most natural impulses. It is a thing I would do myself.” The tide eventually changed for good, and the practice of fans keeping foul balls became entrenched. World War II was another time when patriotic fans and owners worked together to funnel the fouls off to servicemen. A ball in the Hall of Fame’s collection is even stamped “From a Polo Grounds Baseball Fan,” one of the more than 80,000 pieces of baseball equipment donated to the war effort by baseball by June 1942.

One of those baseballs may well have been involved in one of the strangest of all foul ball stories. In a military communique datelined “somewhere in the South Pacific,” the story is told of a foul ball hit by Marine Private First Class George Benson Jr., which eventually traveled 15 miles. Benson’s batting practice foul looped up about 40 feet in the air, where it smashed through the windshield of a landing plane. The ball hit the pilot in the face, fracturing his jaw and knocking him unconscious. A passenger, Marine Corporal Robert J. Holm, muttering a prayer, pulled back on the throttle and prevented the plane from crashing, though he had never flown before. The pilot recovered momentarily and brought the plane to a landing at the next airstrip, 15 miles away.

In 1996, at the age of 71, former President Jimmy Carter made a barehanded catch of a foul ball hit by San Diego’s Ken Caminiti, while attending a Braves game. “He showed good hands,” said Braves catcher Javy Lopez.

With foul balls by this time an undeniable right for fans at the ballpark, what are your actual chances of catching a foul ball at a game? Well, to start with, the average baseball is in play for six pitches these days, which makes it sound as though there will be many chances to catch a foul ball in each game. While comprehensive statistics are not available, various newspapers have sponsored studies which, uncannily, seem quite often to come down to 22 or 23 fouls into the stands per game.

That seems like a healthy number until you look at average major league attendance at games. In the year 2000, the average game was attended by 29,938 fans. With 23 fouls per game, that works out to a 1 in 1,302 chance of catching a foul ball. With numbers like that, no wonder it feels so special to catch a foul ball. Nevertheless, those who yearn to catch a foul ball can improve their chances. I have listed some tips to help you bring home that elusive foul ball. Good luck!

Original Publish date May 8, 2025.

https://weeklyview.net/2025/05/08/bob-fellers-happy-mothers-day/

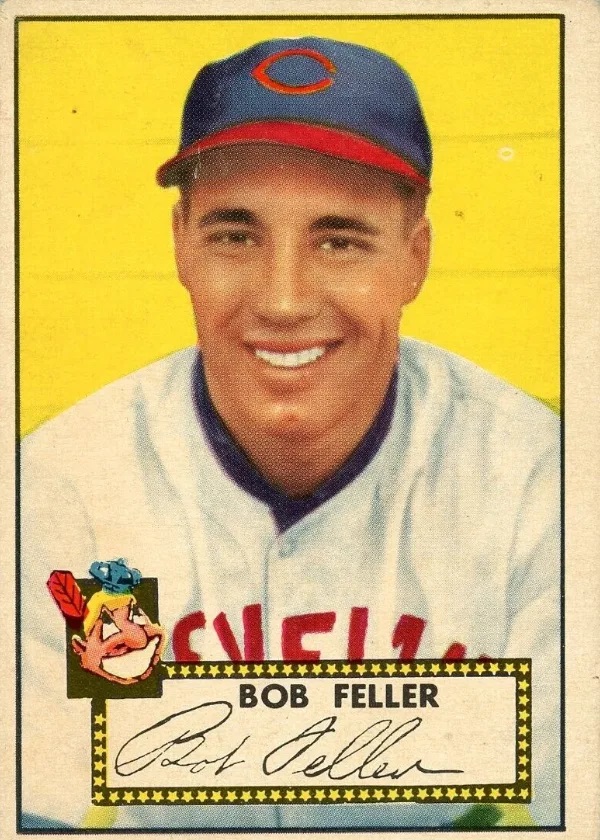

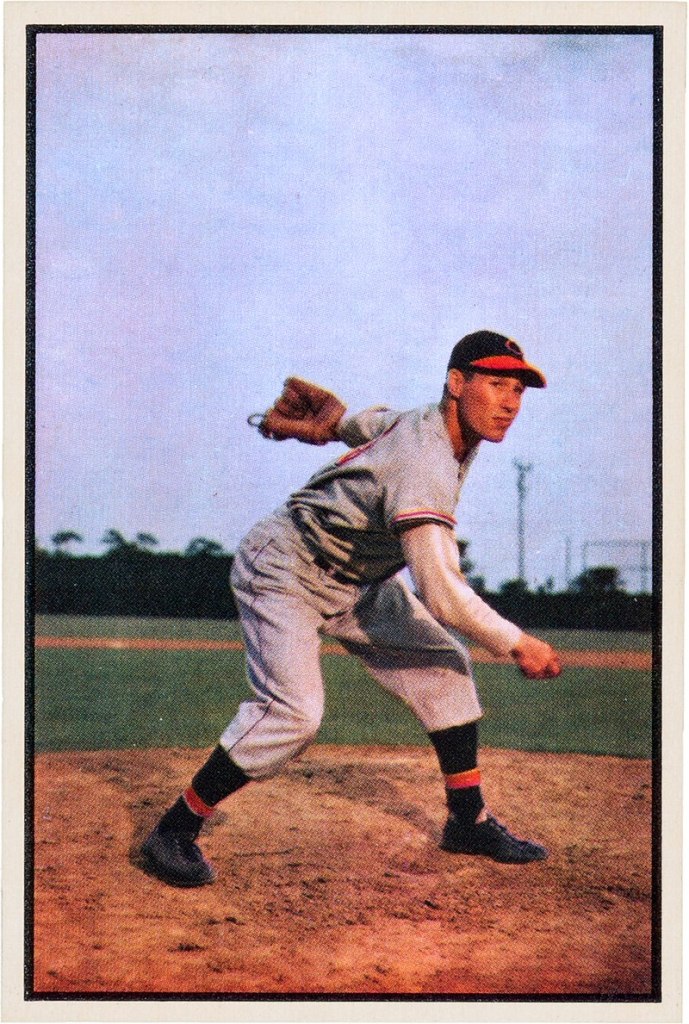

So what did you get for Mother’s Day this year? I hope it was something fun, delicious, or useful, but just in case the answer was nothing, this article might make you feel a little better. Every year, as the boys of summer take the field anew, I try to dig up a baseball story that you may have never heard of before. Or, if you’ve heard of it, perhaps you’re not familiar with or don’t recall all the details. I was lucky enough to meet Baseball Hall of Famer Bob Feller on several occasions. I suppose the most memorable was on July 27, 1984. That was the day of the Cracker Jack Baseball Old-Timers Dream Game at the Hoosier Dome Downtown. I was midway through my term as Deputy Auditor for the state of Indiana, and my office was a short walk to the Dome and an even shorter walk to the Embassy Suites Hotel where the players were staying. So I strolled over and took an extended lunch hour to see if I could meet any of the players as they checked in. I was fortunate that day and had the opportunity to meet Joe DiMaggio, Sal “The Barber” Maglie, Billy Williams, Tony Oliva, Don Larsen, Minnie Minoso, Don Newcombe, Luke Appling, and Bob Feller. Mr. Feller was a gentleman and we talked for a little bit after he checked in. I told him that in my opinion, he was (along with Nolan Ryan and Bob Gibson) one of the three greatest pitchers of my lifetime. I asked him if he could still throw (I think he was 66 at the time) and if so, how fast can he bring it. He answered, “Well, I could still hit 85-90 mph, I guess. If I didn’t want to comb my hair for a month.”

This story is about Bob Feller and his mom on Mother’s Day 1939. Robert William Andrew Feller, nicknamed “the Heater from Van Meter”, “Bullet Bob”, and “Rapid Robert”, was born on November 3, 1918, in Van Meter, Iowa. As a teenager, Feller was a shortstop/outfielder, but by the age of 15, he began to pitch and never looked back. In 1936, Feller was signed by legendary Cleveland Indians scout Cy Slapnicka for one dollar and an autographed Indians team baseball. A prodigy who bypassed baseball’s minor leagues, Feller made his Major League debut at the age of 17 in a relief appearance against the Washington Senators on July 19, 1936. A month later, on August 23, Feller made his first career start against the St. Louis Browns. Feller struck out all three batters he faced in the first inning on his way to recording 15 strikeouts (highest ever at the time for a starting pitcher’s debut) and earned his first career win. Three weeks later, he struck out 17 in a win over the Philadelphia Athletics, tying Dizzy Dean’s single-game strikeout record. He finished that first season with a 5–3 record over 14 games, 47 walks and 76 strikeouts in 62 innings. Then, Feller traveled back to Van Meter for his Senior Year of high school. The governor of Iowa met him at the door on that first day.

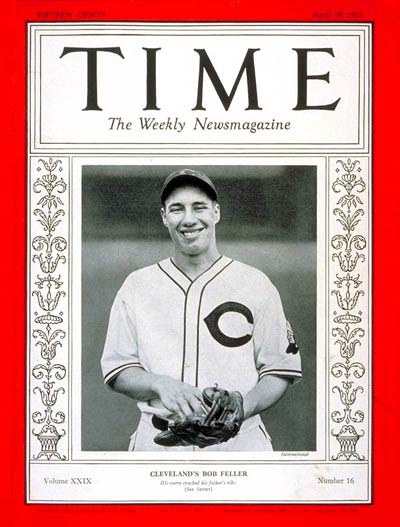

For the start of the 1937 season, Feller appeared on the cover of the April 19, 1937, issue of Time magazine. Rookies appearing on magazine and video game covers have been a longtime curse in the sports world. Feller was no different. After that Time cover, during his first appearance of the season on April 24, Feller blew out his elbow throwing a curveball. He spent April and May healing and traveled back to Van Meter to graduate high school in May in a ceremony that was aired nationally on NBC Radio. For the 1937 season, Feller finished 9-7 despite his 0-4 start. He allowed only 116 hits while striking out 150 batters against a paltry 106 walks pn just under 149 innings.

For the 1938 season, Feller led all pitchers with 208 walks and 240 strikeouts. Feller pitched in 39 Major League games during the 1938 regular season finishing with 17 wins, 11 losses, and 1 save. He allowed 225 hits and finished with a 4.08 E.R.A. with no hit batters, no wild pitches, and no intentional walks. On April 20, 1938, Feller pitched the first of his 12 career one-hitters in the Cleveland Indians’ 9-0 win over the St. Louis Browns. His biggest fan, his mother Lena, was bedridden and sick with pneumonia, so she could only listen to her son’s milestone game on the radio and cheer from home. It was the Indians’ second game of the new season Cleveland’s fireballing right-hander was nearly unhittable. The only hit came in the sixth inning off a weak grounder back to the mound by St. Louis Browns’ catcher Billy Sullivan who beat out an infield hit. Two-time all-star and 1935 batting champion Buddy Myer told the papers, “Bob Feller’s fastball comes at you looking like a shirt button-and as easy to hit.”

Since it was her son’s first game of the season, the Feller house was full of Iowa newspaper reporters, hungry for quotes and reactions from the phenom’s parents. “That’s fine,” Feller’s mother said to her husband, “but it’s a shame he couldn’t have had a no-hit game.” Her nonplussed reaction was no surprise when it came to her son’s prowess on the mound. Lena C. Feller was quite used to her son’s greatness and habit of throwing no-hitters. In 1936, he pitched five no-hitters for Van Meter High School before he went on to help the Indians in the season, all before graduating high school in 1937. Growing up on a farm west of Des Moines, Feller developed great strength and broad shoulders while performing his daily chores. That work helped him throw blazing fastballs. When he was 8 years old, he threw a baseball so hard it broke three of his father William Andrew Feller’s ribs. The elder Feller built his son a ballfield one-quarter mile east of the farmhouse, complete with bleachers and a concession stand. The ballfield has been called the “original Field of Dreams”. That farm was federally designated as a historic site in 1999. In his 2012 biography, Feller stated that if he could relive any moment of his life, it would be “Playing catch with my dad between the red barn and the house.”

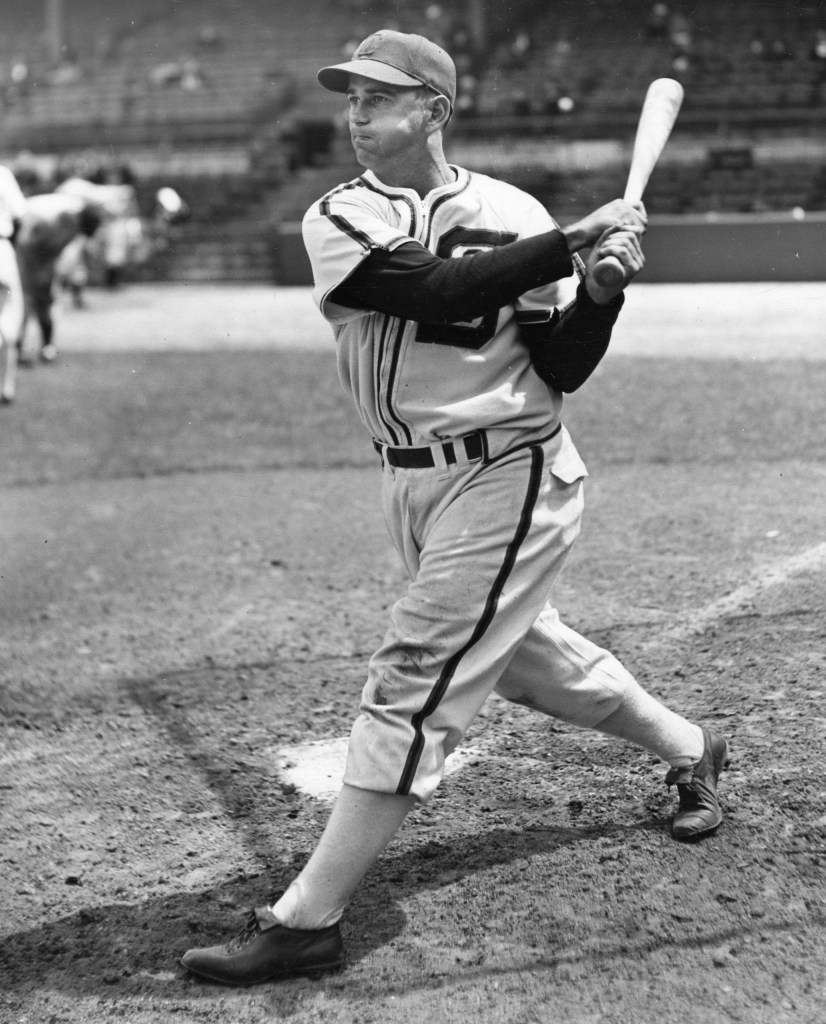

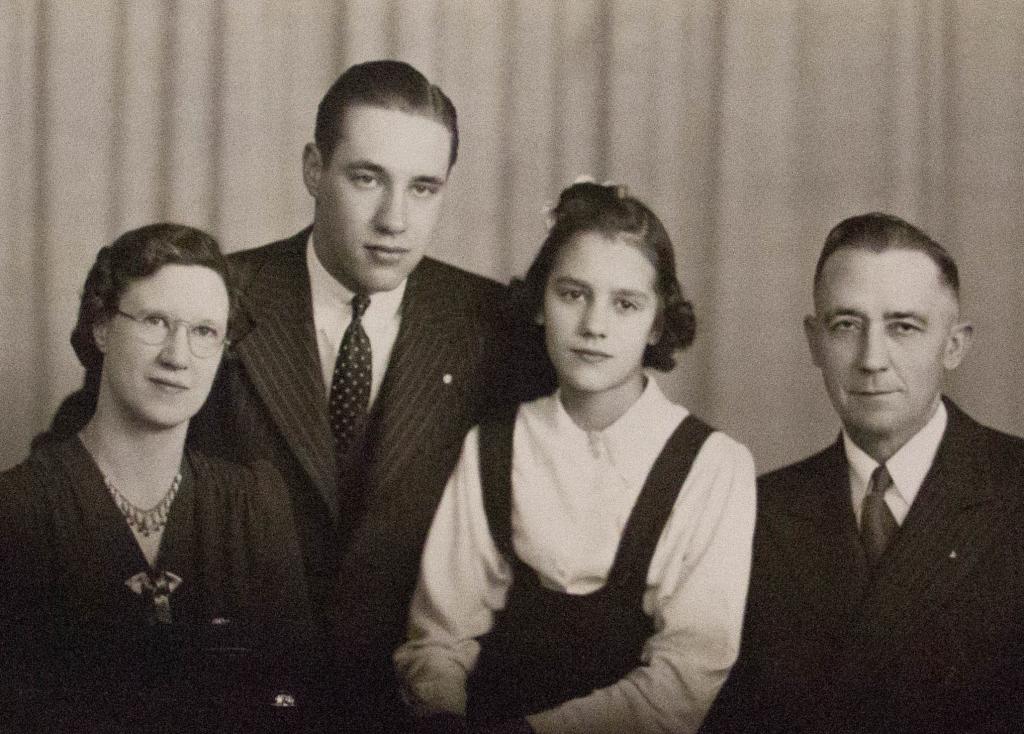

Although already an all-star, 1939 was Bob Feller’s breakout season. He would lead the American League in wins (24), complete games (24), and innings pitched (296 and 2⁄3), and he led the majors for a second consecutive year in both walks (142) and strikeouts (246). And while Feller would repeat as an all-star in 1939, it was an incident on Sunday, May 14, 1939, Mother’s Day, that would be remembered by baseball fans for generations to come. Lena and Bill Feller, along with their 10-year-old daughter Marguerite and over 700 fans from Van Meter, made the 5-hour, 350-mile trip from Iowa to Comiskey Park in Chicago to see their 20-year-old hometown hero pitch against the White Sox in front of 28,000 fans. The Feller family sat in front-row box seats on the first baseline behind the visitors’ dugout.

In the last half of the third inning, Indians up 6 to 0, Feller delivered a pitch to right-handed palehose 3rd baseman Marv Owen. Feller threw a fastball at which Owen swung on hard but late. The foul ball screamed towards the first baseline and into the stands behind the Indians’ dugout, and a horrific CRACK! echoed onto the field. Instinctively, Rapid Robert Feller watched helplessly as the ball struck his mother above her eye, breaking her eyeglasses. News accounts differ as to whether it was her left eye or right eye, but the result was certain: the lenses shattered, lacerating her nose, eyes, and forehead. Blood poured from her eyelid and forehead. The crowd gasped, the Iowa fans shrieked, and Bob Feller froze on the pitcher’s mound. For a few moments stood “stark still,” visibly shaken and agonizing over the drama in the stands. Bob dashed to the box and watched helplessly as she was led off to Chicago’s Mercy Hospital, where stitches were required. The game was delayed as Cleveland Indians trainer Max “Lefty” Weisman rushed into the stands to tend to Mrs. Feller. Lefty escorted her “to a spot below the stands” where he gave Mrs. Feller emergency treatment. He assured his young pitcher that the wounds were not serious before, aided by Lena’s husband and daughter, helping her to a nearby car and driving her to Mercy Hospital. As soon as Lena was safely on her way, Feller retook the mound and struck Owen out. “There wasn’t anything I could do,” Feller later said, “so I went on pitching.” The incident shook him up, and unable to fully concentrate on the game, Feller allowed the White Sox to score three runs before he regained his composure. Settling down, Feller won the game 9 to 4.

At the hospital, 45-year-old Lena received six stitches to close the deepest cut. Doctors determined that Lena probably suffered a mild concussion, but luckily, an X-ray examination determined that her skull was not fractured and no bones were broken. The hospital announced that they expected her to make a full recovery. With the game now over, Bob sped to the hospital to check on his mom. He walked into Lena’s hospital room to find her sitting up in the hospital bed with her head swathed in bandages. He rushed to the bedside and embraced his mother in a hug and she said, “Everything is all right, I just didn’t see that ball coming.” Seeing that his mom was battered and bruised, but otherwise all right, Bob reminded her of his promise to win the game as a Mother’s Day present, which he did. Ironically, it was Bob Feller Day at the ballpark, so Bob was the one who received a gift that day in the form of a brand new portable radio presented before the game from the Iowa delegation. It was his sixth victory of the season, and Feller held the White Sox to six hits, seven walks, and struck out six batters. Another visitor to Lena’s room that day was Kennesaw Mountain Landis, former Hoosier (Delphi & Logansport) and sitting Commissioner of Major League Baseball, whose office was in Chicago.

One newspaper, the May 15, 1939, Lancaster (Ohio) Eagle-Gazette, snarked off after the incident. “Bob Feller will ring up around $10,000 (in today’s money) on the side this year from his endorsements of candy, baseball equipment, breakfast foods, and what have you. That little sum should take care of Master Robert’s [problems].” As detailed above, Feller would recover nicely from the incident and have one of the best seasons of his career. It must be noted that the next year on April 16th, Opening Day of the 1940 season, Bob Feller threw his first no-hitter against, you guessed it, the Chicago White Sox at Comiskey Park. This time Marv Owen was not in the lineup, having been sold to the Boston Red Sox in December 1939, and Feller’s parents were safely at home listening to the game on the radio.