Tag: The House Where Lincoln Died

Osborn H. Oldroyd’s Greatest Fear.

Original Publish Date March 6, 2025.

https://weeklyview.net/2025/03/06/osborn-h-oldroyds-greatest-fear/

My wife and I recently traveled to Springfield, Illinois for a book release event (actually two books). One book on Springfield’s greatest living Lincoln historian, Dr. Wayne C. “Doc” Temple, and the other on my muse for the past fifteen years, Osborn H. Oldroyd. I have fairly worn out my family, friends, and readers with the exploits of Oldroyd over the years. He has been the subject of two of my books and a bevy of my articles. Oldroyd was the first great Lincoln collector. He exhibited his collection in Lincoln’s Springfield home and then in the House Where Lincoln Died in Washington DC from 1883 to 1926. Oldroyd’s collection survives and forms much of the objects in Ford’s Theatre today.

For this trip, we traveled up from the south to Springfield through parts of northwest Kentucky and southeast Missouri. What struck us most were the conditions of the small towns we drove through. Today many of these little burgs and boroughs are in sad shape, littered by once majestic brick buildings featuring the names of the merchants that built them above the doorways, eaves, and peaks of their frontispieces in a valiant last stand. Most had boarded-up windows and doors and some with ghost signs of products and services that disappeared generations ago.

They are tightly packed and many share common walls. We were amazed how many of them have caved-in or worse, burnt down. The caved-in buildings are the work of Father Time and Mother Nature, but the burnt ones look as if the fires were extinguished just recently. My wife deduces that these are likely the result of the many meth labs that blight these long-forgotten, empty buildings. Indeed, a little research reveals that these rural areas do lead the league in these hastily constructed, outlaw drug factories.

Of course, that got me thinking about Oldroyd’s museum. Oldroyd lobbied for decades to have his collection purchased by the U.S. government and preserved for future generations to explore. The Feds eventually purchased it in 1926 for $50,000 (around $900,000 today). For over half a century while assembling his collection, Oldroyd had one great fear: Fire. Visiting the House Where Lincoln Died today, the building remains unique in size and architecture compared to those around it. In Oldroyd’s day, smoking cigars, pipes, and cigarettes indoors was as prevalent as carrying cell phones and water bottles are today. The threat of fire was very real for Oldroyd.

The March 20, 1903, Huntington Indiana Weekly Herald ran an article titled “A Visit to the Lincoln Museum in Washington City.” After describing the relics in the collection, columnist H.S. Butler states, “It is hoped the next Congress will purchase this collection and care for it. Mr. Oldroyd is not a man of means such as would enable him to do all he would like, and it seems to me a little short of criminal to expose such valuable relics, impossible to replace, to the great risk of fire. I understand Congressman [Charles] Landis, of Indiana, is trying to get the collection stored in the new Congressional Library, in itself the handsomest structure, interiorly, in Washington. I hope that his brother, the congressman from the Eleventh District [Frederick Landis], will lend his influence to Senators [Charles] Fairbanks and [Albert] Beveridge to urge forward the same end.”

Fifteen years later, the Topeka State Journal described an event that fueled Oldroyd’s concern. “May 21 [1918]-a few days ago the Negro cook in the kitchen of a dairy lunch spilled some fat on the fire and the resulting blaze was extinguished with some difficulty. The unique feature of this trifling accident was that, had the blaze gotten beyond control, it would probably have destroyed a neighboring house in which is the greatest collection in the world of relics, manuscripts, and books bearing upon the life and death of Abraham Lincoln…Sixty feet away from the room in which Lincoln died are three kitchens of restaurants and a hotel. More than one recent fire scare has caused alarm over the danger that threatens these relics.”

The February 11, 1922, Dearborn [Michigan] Independent reported, “A vagrant spark, a carelessly tossed cigarette or cigar stub, an exposed electric wire might at any time mean the destruction of the collection and the building which, of course, is itself a sacred bit of Lincolniana.” The January 21, 1924, Daily Advocate of Belleville, Ill. reported “The collection is contained in a small and overcrowded room of the house opposite Ford’s Theatre, with two restaurants across a narrow alleyway constituting a constant fire menace…it is likely that the U.S. Government will request that the Illinois Historical Society return the bed in which Lincoln died, that it may again be placed in the room it occupied on that fateful night and the entire setting restored.” Due to that unresolved fire threat the bed was never returned and is today on display at the Chicago History Museum. A 1924 Christmas day article in the Washington Standard 1924 described, “There are a number of restaurants in the block at the rear, and once an oil supply house did business close at hand. On two occasions there have been fires in the neighborhood.”

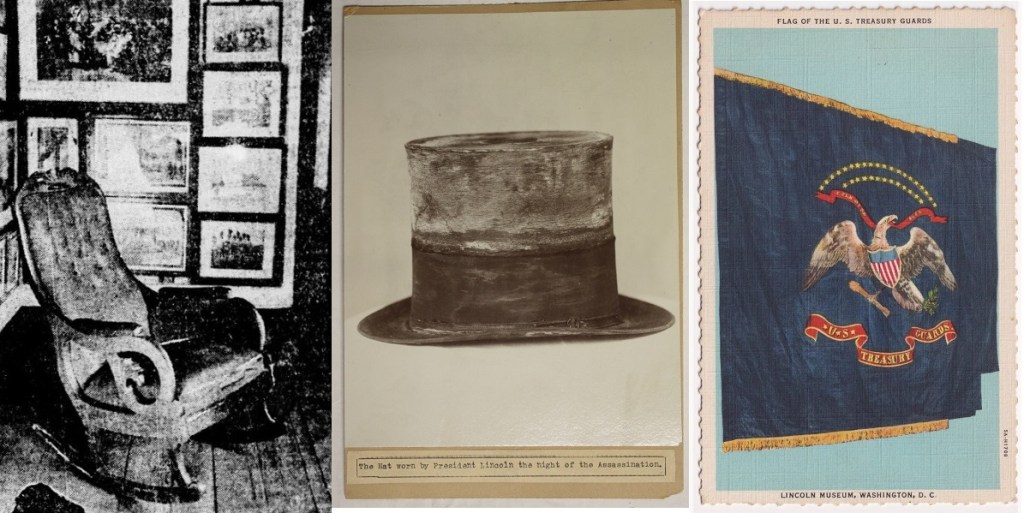

The July 6, 1926, Indianapolis News speculated, “The government will add to the collection the high silk hat Lincoln wore to the theatre that fatal night, the chair in which he sat in the presidential box, and the flag in which Booth’s foot caught. The flag now hangs in the treasury, while the hat and chair are in storage. These articles formerly were in the Oldroyd collection, but after a fire in the neighborhood some years ago, officials of the government took them back, fearing that they might be destroyed.” The February 18, 1927, Greenfield [Indiana] Reporter stated, “The plan proposed by Senator Watson, of Indiana, and Rep. Rathbone of Illinois, is to remodel the building to protect it against the danger of fire and the ravages of age. They would…place in it the famous Oldroyd collection of Lincoln relics.” Fire remained a nightmare for Oldroyd right up to the day he died on October 8, 1930.

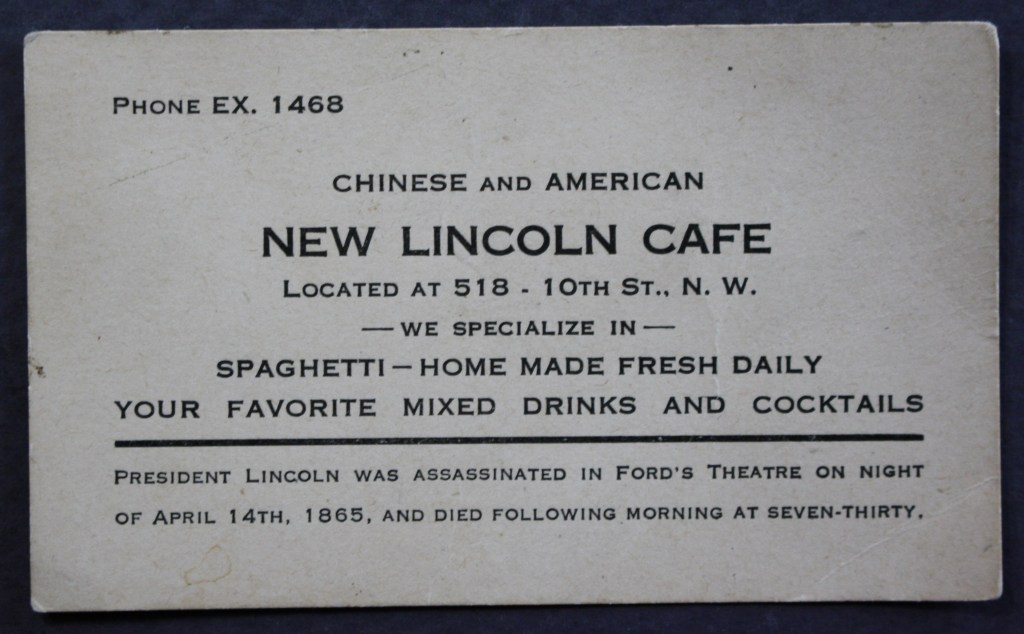

Ironically, after that book signing I found myself browsing the bookstore. I found there a 2 1/2” x 4” business card from the New Lincoln Cafe in the adjoining building to the north of Oldroyd’s Museum (at 516 10th St. NW). Putting aside the fact that I have a personal affinity for old business cards, the item called out to me and made me wonder about the businesses that had been neighbors to this hallowed spot over the generations.

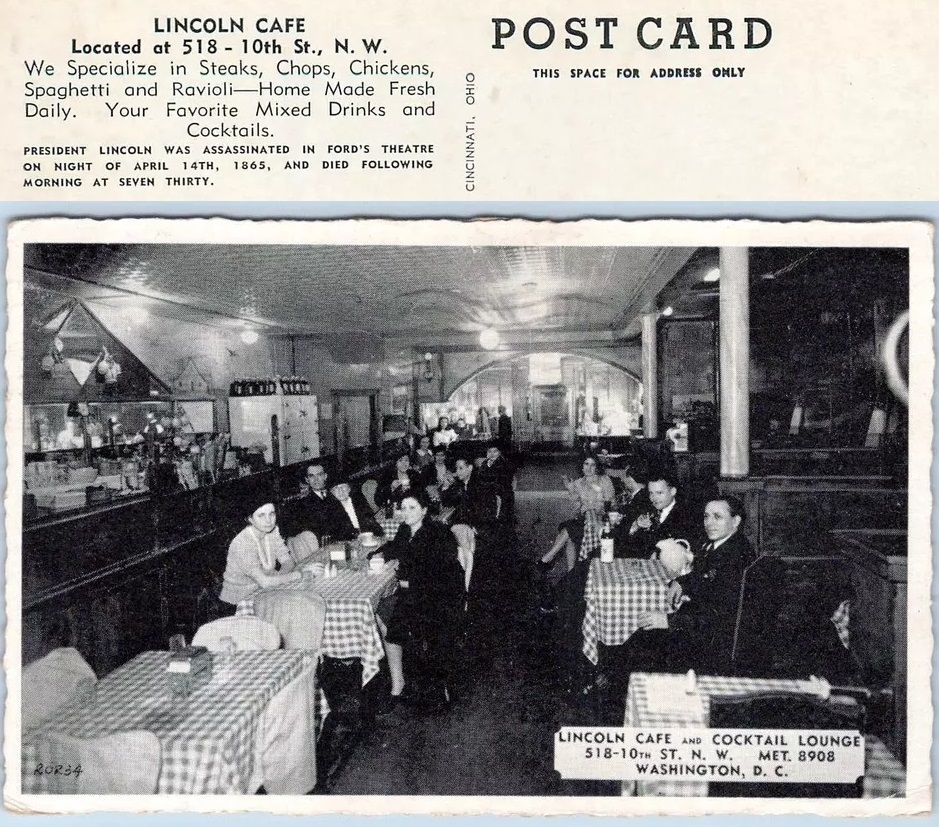

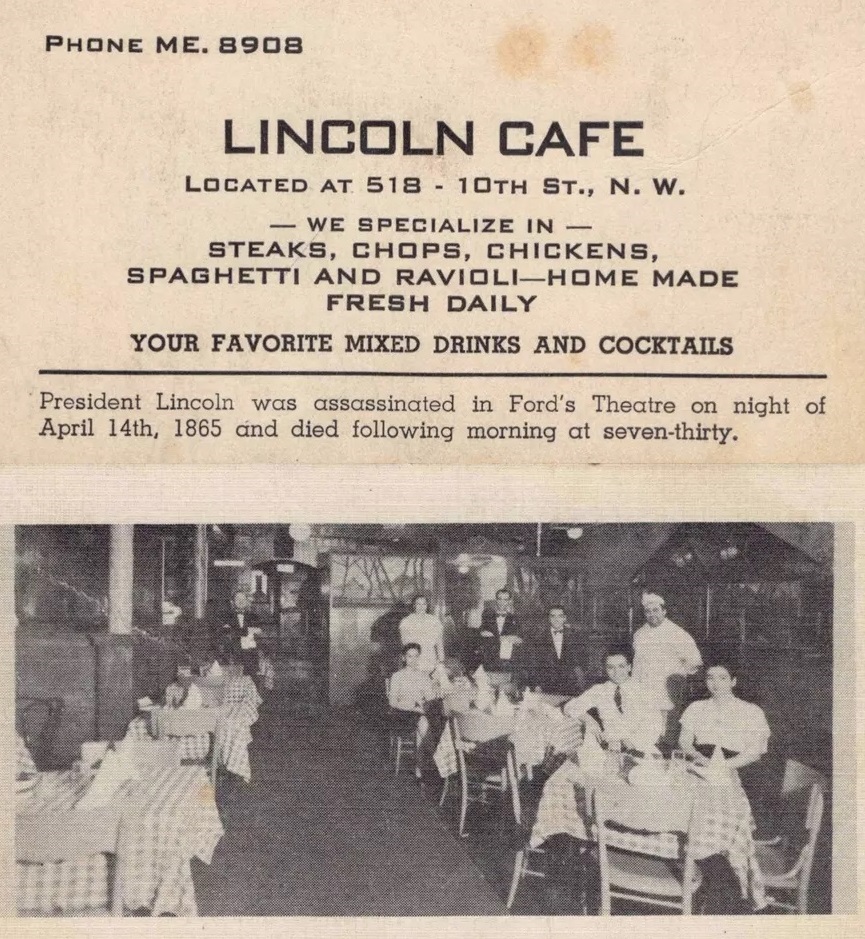

The card reads: “Chinese and American New Lincoln Cafe. Located at 518 10th St., N.W. Phone EX. 1468. We Specialize In Spaghetti-Home Made Fresh Daily. Your Favorite Mixed Drinks And Cocktails. President Lincoln Was Assassinated In Ford’s Theatre On Night Of April 14th, 1865, And Died Following Morning At Seven-Thirty.” A check of the records indicates that this restaurant remained next to the museum from the late 1930s to the early 1960s. This was just one of the businesses to call that space home over the generations.

Located in the Penn Quarter section of DC, the building was built sometime between 1865 to 1873. It envelopes the entire north side and part of the northwest back of the HWLD. It is 4 stories tall and features 11,904 square feet of retail space. One of the earliest storefronts to appear there was Dundore’s Employment Bureau which served D.C. during the 1870-90s. Ironically, when Dundore’s moved three blocks south to 717 M Street NW, the agency regularly advertised jobs at businesses occupying their old address for generations to come. Above the Dundore agency was Mrs. A. Whiting’s Millinery, which created specialty hats for women. The Washington Evening Star touted Mrs. Whiting’s “Millinery Steam Dyeing and Scouring” business for their “Imported Hats and Bonnets”. A 3rd-floor hand-painted sign on the bricks of the building advertising Whiting’s remained for years after the business vacated the premises, creating a “ghost sign” visible for many years as it slowly faded from view.

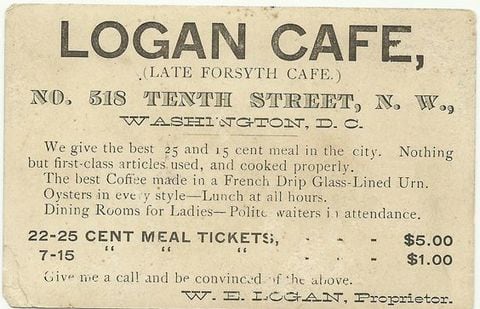

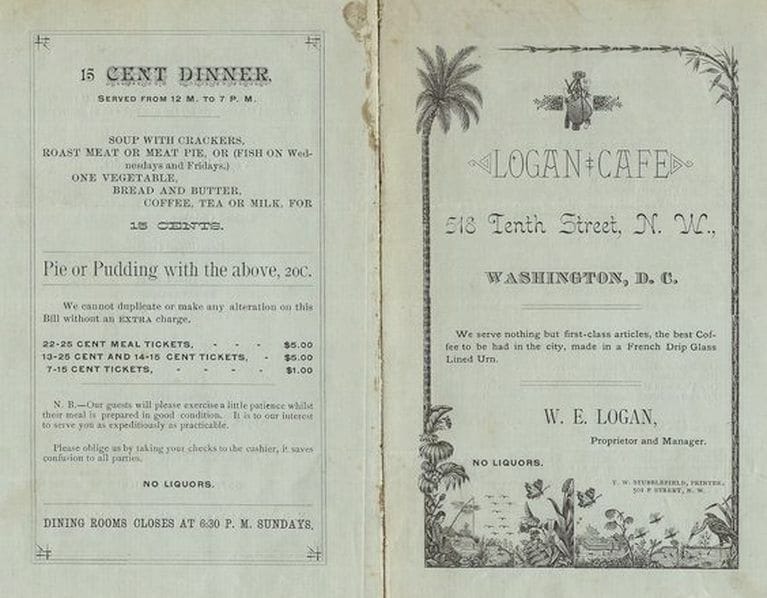

The Forsyth Cafe seems to have been the first bistro to pop up next to the Oldroyd Museum. In late February/March 1885 (in the leadup to Grover Cleveland’s first Presidential Inauguration), DC’s Critic and Record newspaper’s ad for the cafe decries, “Yes, One Dollar is cheap for the Inauguration supper, but what about those excellent meals at the Forsythe Cafe for 15 Cents?” The Forsyth continued to advertise their meals from 15 to 50 cents but by late 1886, they were gone, replaced by the Logan Cafe. The Logan offered 15 and 25-cent breakfasts, “Big” 10-cent lunches, and elaborate 4-course dinners of Roast beef, stuffed veal, lamb stew, & oysters. Proprietor W.E. Logan’s claim to fame was “the best coffee to be had in the city, made in French-drip Glass-Lined Urn” and “Special Dining Rooms for Ladies-Polite waiters in attendance” and his menus warned “No Liquors” served.

The June 4, 1887, Critic and Record reported on a “friendly scuffle” at the Logan between two “colored” employees when cook Charles Sail tripped waiter William Butler who hit his head on the edge of a table and died the next morning at Freedman’s Hospital. The men were described as best friends and the death was deemed an accident. By late 1887, the Logan disappears from the newspapers. From 1897 to 1897, the building was home to the Yale Laundry. The Jan. 7, 1897, DC Times Herald reported on an event that likely added to Oldroyd’s anxiety. The article, titled “Laundry is Looted” details a break-in next door to the museum during which a couple of safecrackers got away with $85 cash including an 1883 $5 gold piece.

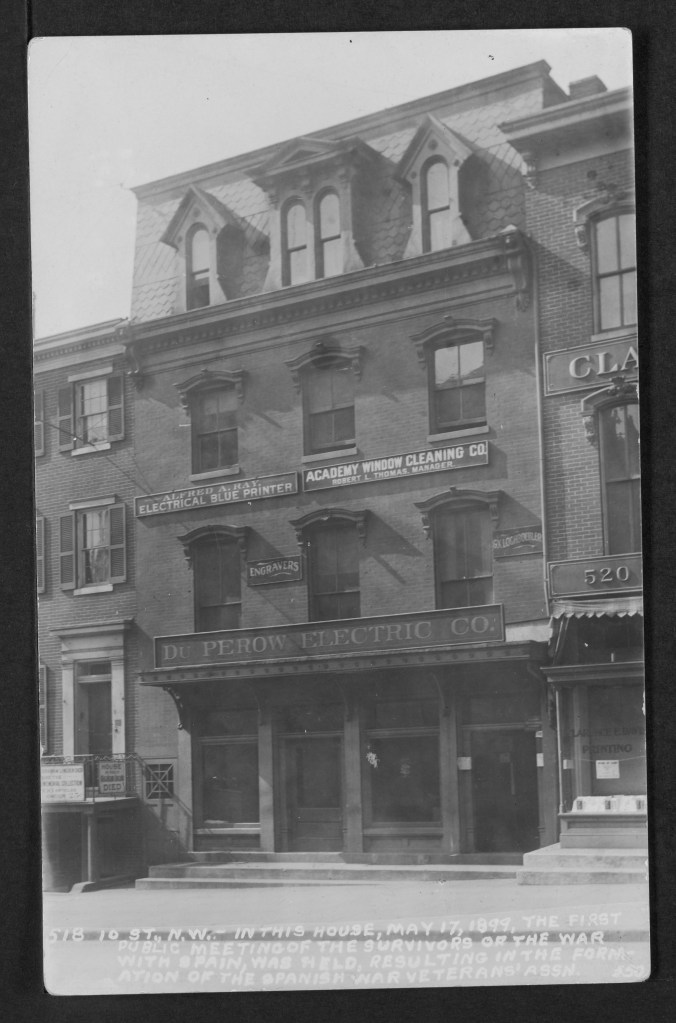

A real photo postcard in the collection of the District of Columbia Public Library pictures the building during Yale Laundry’s tenure captioned, “In this house the first public meeting of the survivors of the war with Spain, was held on May 17, 1899, resulting in the formation of the Spanish War Veterans’ Association.” The Dec. 1, 1900, Washington Star notes the addition of Harry Clemons Miller’s “Teacher of Piano” Studio and by 1903, the “Yale Steam Laundry” appeared in the DC newspapers at the address.

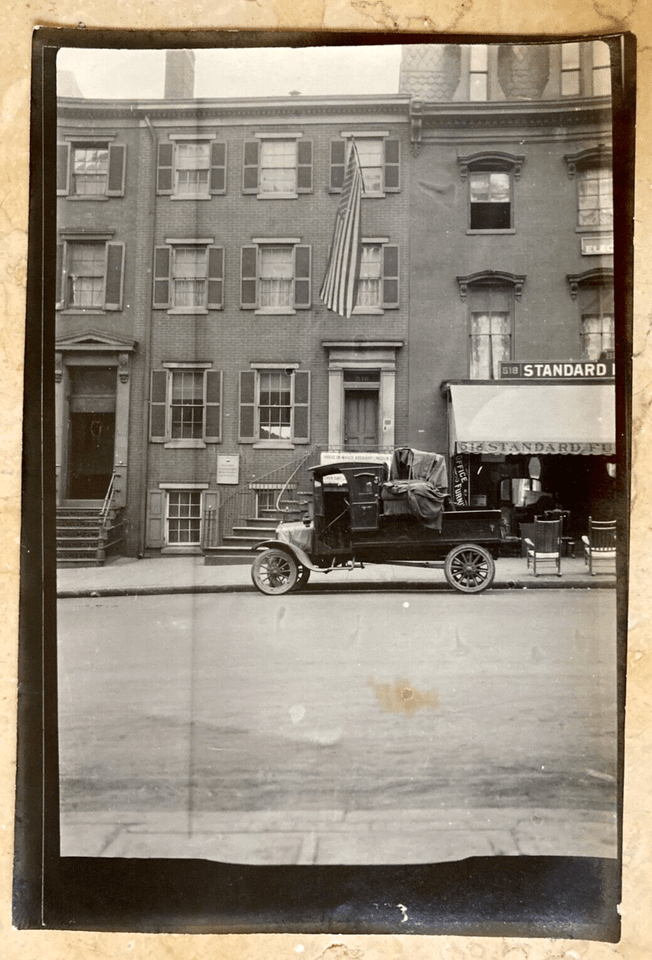

In 1909, Du Perow Electric Co. (AKA as “Du Pe”) and partner Alfred A. Ray “Electrical Blueprints” occupied the building. A window cleaning company occupied room # 9 and a leather goods store was located there during this same period. By 1912, the storefront was occupied by the Standard Furniture Co. At least one photo survives presenting an amusing scene of a furniture truck blocking the entrance to Oldroyd’s museum. Amusing to the viewer today but most assuredly not to the museum curator back in the day. Eventually, the restaurants, bars, and cafes that worried Oldroyd began to come and go, among them, the Lincoln Cafe & Cocktail Lounge, whose sign was dominated by the words “Beer Wine.” It appears that during the 1920-50s, a Pontiac, DeSoto, Plymouth Motor Car dealer known as “News & Company” kept an office in the building, with the car lot and gas station across the street.

Old-timers remember a long-term tenant known as “Abe Lincoln Candies” that occupied the space from the 1950-70s. Other recent tenants included Abe’s Cafe & Gift Shop, Bistro d’Oc and Wine Bar, Jemal’s 10th Street Bistro, Mike Baker’s 10th St Grill, and the I Love DC gift store, and last year, The Inauguration-Make America Great Again Store, who one Yelp reviewer complained was crowded with outdated, sketchy clothing and that “they make u give them a good review before they give u a refund kinda scummy.”

As for the building on the opposite side of Oldroyd’s museum at 514 Tenth St. NW, it remained a residence until 1922 when a $55,000, 10-story concrete & steel building with steam heat and a flat slag roof was built. Designed by architect Charles Gregg and built by Joseph Gant, the sky-scraper, known as the Lincoln Building, dwarfed the Oldroyd Museum. It was home to several businesses, including the Electrical Center (selling General Electric TVs, radios, and appliances) and the Garrison Toy & Novelty Co, its modern construction alleviated any concern of fire.

It must be noted that many great collections of Lincolniana fell victim to fire in the century and a half after Lincoln’s death. The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 consumed many Lincoln objects, documents, and personal furniture that had been removed from the Springfield home after the President’s departure to Washington DC. On June 15, 1906, Major William Harrison Lambert (1842-1912), recipient of the Congressional Medal of Honor and one of the Lincoln “Big Five” collectors, lost much of his collection in a fire at his West Johnson St. home in Germantown, Pa. Among the items lost were a bookcase, table, and chair from Lincoln’s Springfield law office and the chairs from Lincoln’s White House library. The threat of fire was a constant waking nightmare in Oldroyd’s life. While he did his best to control what went on inside his museum, he had no control over what happened outside. His life’s work of collecting precious Lincoln objects, over 3,500 at last count, could be gone in the flash of a pan.

ADDITIONAL IMAGES.

Lewis Gardner Reynolds, Carnation Day & Abraham Lincoln. PART II

Original publish date: February 6, 2020

https://weeklyview.net/2020/02/06/lewis-gardner-reynolds-carnation-day-abraham-lincoln-part-2/

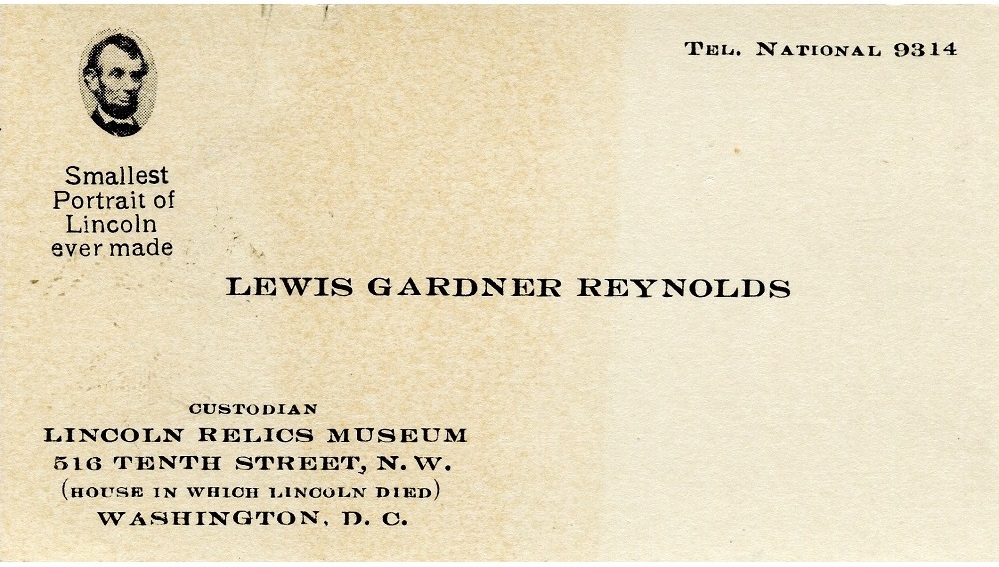

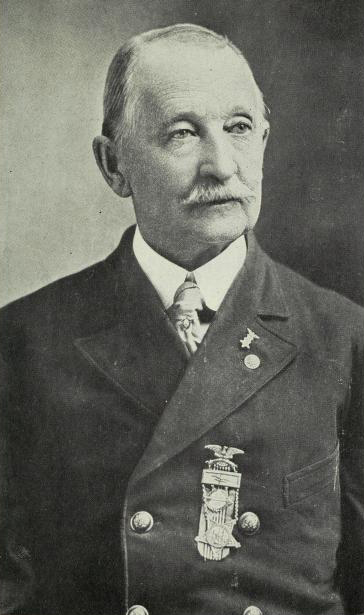

Last week the oft-forgotten holiday known as “Carnation Day” was detailed in Part I of this series. The holiday, today observed mostly only in Ohio, was created to commemorate assassinated President William McKinley on his birthday (January 29) by wearing his favorite flower, a red carnation, to honor him. The formal recognition of the holiday was due largely to the efforts of a man named Lewis Gardner Reynolds from Richmond, Indiana. In 1903, Reynolds formed the Carnation League of America to establish the custom of observing the McKinley floral holiday. That alone might be enough for most historical resumes, but not for Mr. Reynolds. Among this (and other noteworthy achievements) it should be noted that Reynolds was the last person to meet the living Abraham Lincoln.

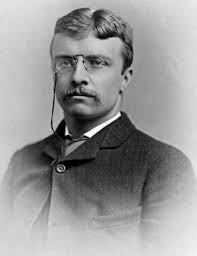

Mr. Reynolds was born at Bellefontaine, Ohio on June 28, 1858, and grew up in Dayton, Ohio. In Dayton, he worked for his father at the Reynolds & Reynolds Co., manufacturing notebooks and other school supplies. Later he started his own company, manufacturing paper cartons, and served for 10 years as a member of the school board of that city. While in Ohio, Mr. Reynolds came to know many American leaders, including President McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt, and Ohio politicos Myron T. Herrick, and Mark Hannah. In 1896 he married Miss Jeanette Lytle in Dayton. She died in 1903 and in 1909 he married Mary V. Williams of Richmond, Indiana. The couple relocated to Richmond and during World War I, Reynolds was prominent in organizing Liberty Loan drives for the war effort.

Upon the death of Teddy Roosevelt on January 6, 1919, Lewis G. Reynolds was made chairman of the Wayne County Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Committee. Reynolds led Indiana’s fundraising plans to honor Roosevelt with monuments in Washington D.C., the national shrine at Oyster Bay, Long Island, restoration of his birthplace at No. 28 West Twenty-Second Street in New York City, and lastly, through an endowment fund, “to perpetuate Colonel Roosevelt’s ideals of courageous Americanism.” The next year, Reynolds traveled to Indianapolis for a speech to the Indiana General Assembly advocating for the construction of the World War Memorial in the capital of the Hoosier state. Thanks in part to his efforts, the resolution was adopted, the memorial built.

After World War I Reynolds led the European Relief Commission, in particular the Wayne County Council headquartered at 1000 Main Street in Richmond. The January 11, 1921 issue of the Richmond Palladium noted, “Lewis G. Reynolds today received the following telegram: “Congratulations on dignified and successful manner in which you are conducting campaign for European relief. The American people are thoroughly aroused to the appealing need of this great mercy call. The need is great. The call urgent. Let mercy impel us to give relief to the starving children of Europe. Herbert Hoover.”

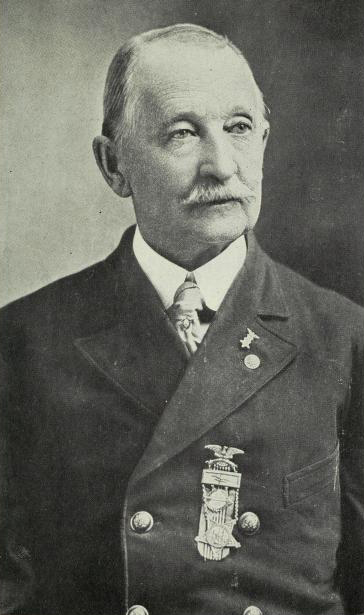

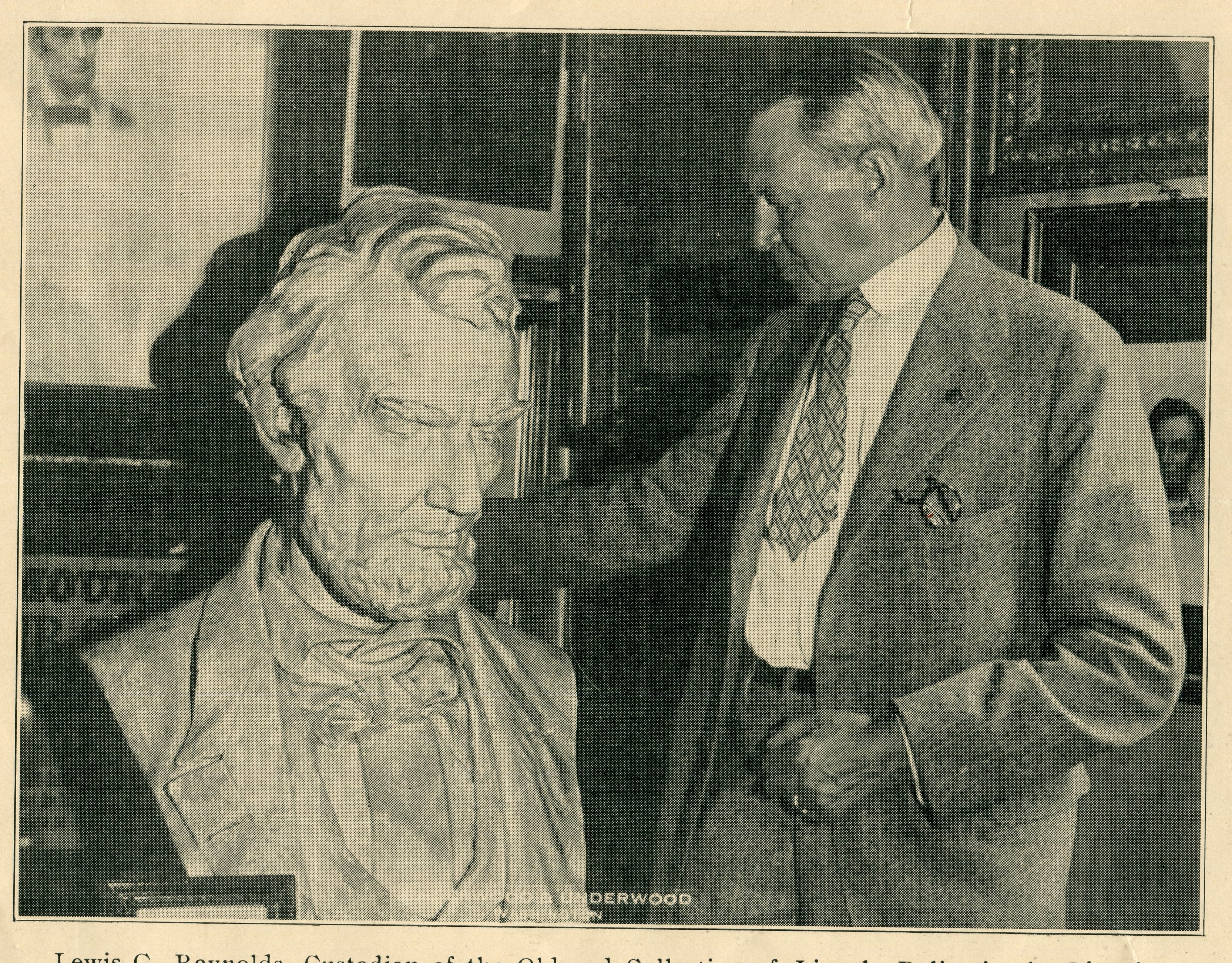

After Osborn H. Oldroyd, the first Lincoln museum curator, sold his collection to the US government in 1926, Reynolds was called to Washington by Col. U.S. Grant, III to take charge of the Oldroyd collection. Ironically, the Reynolds family moved from their house on North Tenth Street in Richmond to their new house on Tenth Street Northwest in Washington D.C.: The House Where Lincoln Died.

A year before Oldroyd’s death, the two old friends were profiled together one final time in the February 12, 1929, Battle Creek Enquirer. “Two men who spend most of their time in the house where Abraham Lincoln died are probably more interested in the anniversary of his birth than anyone else in the country. They are Osborn Oldroyd, aged 87, who has spent 65 years collecting mementos and documents relating to the life of Lincoln, and Lewis Gardner Reynolds, 71, who sat on Lincoln’s knee as a little boy of six…Mr. Reynolds in the last year has shown 20,000 persons from all over the world through the room where Lincoln died.”

So not only was Mr. Reynolds in charge of the world’s largest Lincoln object collection contained within the house where the sixteenth president died, but he could now also entertain visitors with the story of how he, as a six-year-old child, once sat upon Abraham Lincoln’s knee in the White House. In 1929, while the Nation celebrated the 120th anniversary of the Great Emancipator’s birth, Mr. Reynolds recalled that meeting to a local Washington D.C. newspaper reporter. Although not positive about the exact date, Mr. Reynolds said he felt reasonably sure that it was June 28, 1864, his sixth birthday, when the memorable event occurred.

“Father, (Lucius Delmar Reynolds 1835-1913), a captain of one of the companies of the Treasury Guards, was to have a conference with his Commander-in-Chief, and I accompanied him,” Mr. Reynolds said. “While they were discussing the matter of the conference, which lasted nearly an hour, the President picked me up, set me on his knee, and I can feel yet the gentle stroke of that big firm hand as he stroked my head, like the halo of a great benediction. I almost remember his voice. Toward the end of the conference Mr. Lincoln carried me to one of the large windows overlooking the Potomac River, rested me on the deep window seat and stood there with one arm about me while pointing out to the captain some points of vantage he wished him to be familiar with…I saw President Lincoln scores of times,” Mr. Reynolds says, “as father’s duties took him frequently to the Executive Mansion, and he often took me with him. But I recall being actually on Lincoln’s lap and in his arms but once.”

In 1928 Reynolds authored a leaflet titled: “A Wonderful Hour with Abraham Lincoln” which he handed out to friends and special guests visiting the museum. While the leaflet ostensibly tells the story of his encounter with Lincoln, it also offers more details. “The very earliest recollection I have of anything is intimately connected with the Civil War…We removed to Washington and resided there from 1862 to 1866. Father was chief of one of the many bureaus of the treasury department. All the clerks and higher officials of the department were organized into military companies, known collectively as “The Treasury Guards.” They were intensely drilled by officers of the regular army, and as well-equipped as the soldiers in the field, except that they were not uniformed. They represented a potential army of nearly 2,000 men. Their military duties were to be, in case of an emergency, to protect the Treasury Department and the Executive Mansion, nearby. Father was made captain of one of these companies, and to his command was assigned the protection of the White House, and the President. Upon that fact rests my story.”

The Reynolds leaflet further reveals,”Father and mother were at Ford’s Theatre the night of the assassination, and although it was late when they returned home, the general excitement of the night had reached our neighborhood. The newsboys shrill cries of “Extra! Extra! President Lincoln Shot” had awakened everybody in the boarding house. I, too, was awake. Young as I was, I realized what dreadful thing had happened, and I lay wide-eyed in my little trundle bed while father and mother related to the others their personal story of the tragedy. Father, accompanied by several of the men guests, went back to the scene and did not return until after the fateful hour of 7:22 the next morning. I remember as clearly as though it were of yesterday, wearing a wide band of black around the sleeve of my bright plaid jacket, and, carried in father’s arms, of passing the somber catafalque in the rotunda of the Capitol, which inclosed (sic) all that was mortal of the beloved Lincoln. A few weeks later I witnessed the Grand Review of the Army – that wonderful spectacle of the returning boys in blue – which took several days in its passing.”

The Reynolds leaflet further reveals,”Father and mother were at Ford’s Theatre the night of the assassination, and although it was late when they returned home, the general excitement of the night had reached our neighborhood. The newsboys shrill cries of “Extra! Extra! President Lincoln Shot” had awakened everybody in the boarding house. I, too, was awake. Young as I was, I realized what dreadful thing had happened, and I lay wide-eyed in my little trundle bed while father and mother related to the others their personal story of the tragedy. Father, accompanied by several of the men guests, went back to the scene and did not return until after the fateful hour of 7:22 the next morning. I remember as clearly as though it were of yesterday, wearing a wide band of black around the sleeve of my bright plaid jacket, and, carried in father’s arms, of passing the somber catafalque in the rotunda of the Capitol, which inclosed (sic) all that was mortal of the beloved Lincoln. A few weeks later I witnessed the Grand Review of the Army – that wonderful spectacle of the returning boys in blue – which took several days in its passing.”

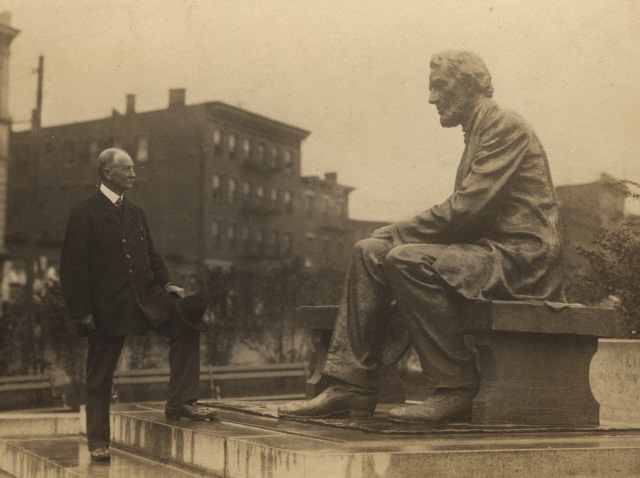

On February 5, 1931, a story and photo of Lewis G. Reynolds appeared in newspapers all around the world. Mr. Reynolds was pictured standing on the spot where Lincoln died and speaking into a CBS radio microphone. The article details the radio address commemorating Lincoln’s upcoming birthday titled, “A World Tour of the Lincoln Museum”. It read in part, “In telling of the Lincoln Museum and the relics it contains, Reynolds said no story of it would be complete without reference to Col. O.H. Oldroyd to whom the world is indebted for the collection. ‘A monument should be erected to that man,’ he declared.”

Mr. Reynolds supervised the removal of the Oldroyd collection out of the House Where Lincoln Died and into Ford’s Theatre across the street. It began on December 8, 1931, and by New Year’s Day of 1932, Oldroyd’s collection had been fully moved into the newly repurposed Ford’s Theatre. The Oldroyd collection officially opened in its new location at 2:00 P.M. on February 12, 1932. In an article for the Washington Sunday Star magazine on February 12, 1933, Reynolds states, “Twenty-five thousand one hundred and eighty-one persons have visited the Lincoln house since it was open to the public and the number will increase from month to month as the rehabilitation of the shrine becomes more widely known.”

Mr. Reynolds continued in charge of the Lincoln Memorial collection until 1936 when he retired after suffering a stroke. He returned to his home at 39 North Tenth Street in Richmond to convalesce but never worked again. Custodian Reynolds met a sad and untimely end. On August 21, 1940, police and fire were called to the Reynolds home at 39 North Tenth Street where, upon entry, Reynolds was found seated in an invalid’s chair seriously burned. His clothing caught fire when the tip of a lighted match ignited his clothing while his nurse, Mrs. Anna Farlowe, was in the kitchen preparing his evening meal. Investigators believed the accident took place while Reynolds was trying to light his pipe. His wife Mary, who heard his screams for help, rushed to his aid, and with Mrs. Farlowe, succeeded in putting out the fire with blankets. Mr. Reynolds was taken to a nearby hospital by ambulance and both women were treated for severe burns on their hands. Lewis G. Reynolds died in Reid Memorial Hospital in Richmond; He was 82 years old. Mr. Reynolds was survived by his widow, Mary V. Reynolds; and two daughters. Mrs. Horace Huffman. Dayton, Ohio, Mrs. John W. Clements, of Richmond; a stepson, Edward B. Williams, of Richmond; 10 grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

Two decades later, in 1960, the Richmond Palladium-Item newspaper profiled the widow of the former curator, offering new insight. The article is titled: “Local Woman Conducted Tours In House Where Lincoln Died.” It reveals, “Mrs. Reynolds and her husband lived on the second floor of the house at 516 Tenth Street, Washington, DC, at the time Mr. Reynolds was curator of the Oldroyd Lincoln Memorial collection. This was from 1928 through 1936. “I never heard anyone ask Mr. Reynolds a question about Mr. Lincoln he could not answer,” Mrs. Reynolds recalls. Her husband acquired the job as curator when he heard Oldroyd wanted to retire… “I have had visitors say to me doesn’t it give you a creepy feeling?” (sleeping in the house where Lincoln died.) Her answer was always “No.” To the reporter, she said, “I never had a creepy feeling. When I thought about it, it was just a feeling of awe and reverence.” Mr. Reynolds described the collection via radio from the Petersen house several times.“

Two decades later, in 1960, the Richmond Palladium-Item newspaper profiled the widow of the former curator, offering new insight. The article is titled: “Local Woman Conducted Tours In House Where Lincoln Died.” It reveals, “Mrs. Reynolds and her husband lived on the second floor of the house at 516 Tenth Street, Washington, DC, at the time Mr. Reynolds was curator of the Oldroyd Lincoln Memorial collection. This was from 1928 through 1936. “I never heard anyone ask Mr. Reynolds a question about Mr. Lincoln he could not answer,” Mrs. Reynolds recalls. Her husband acquired the job as curator when he heard Oldroyd wanted to retire… “I have had visitors say to me doesn’t it give you a creepy feeling?” (sleeping in the house where Lincoln died.) Her answer was always “No.” To the reporter, she said, “I never had a creepy feeling. When I thought about it, it was just a feeling of awe and reverence.” Mr. Reynolds described the collection via radio from the Petersen house several times.“

Finally, the article makes note of the widow Reynolds’s role at the House Where Lincoln Died. “Mrs. Reynolds read the Lincoln Library in the Oldroyd collection. In her study of history and Lincoln material, she qualified herself to talk with visitors on Lincolniana. “I met most interesting people,” Mrs. Reynolds said, “I often took them through the rooms…even the people from the South were pleasant. It was a wonderful experience.”

Lewis Gardner Reynolds accomplished more in his 82 years than most could ever dream of. When he died in 1940, Abraham Lincoln had transcended into secular sainthood and Reynolds was the last tangible connection to the mortal Lincoln. Not only was Lewis Gardner Reynolds the last to encounter the living Lincoln, the Reynolds family (following the Petersons, the Schades, and the Oldroyds) were the last to reside in the House Where Lincoln Died. And of course, he was a Hoosier.

Osborn Oldroyd-Keeper of the Lincoln flame. Part IV

Original publish date: July 27, 2017

I have spent the last 3 weeks retracing the steps I have taken chasing one of my heroes, Osborn Oldroyd. In early June of this year, I was contacted by a Marshalltown, Iowa auction house that informed me of a small group of items they were auctioning off that came from the Oldroyd Museum in Springfield. There were 10 items in the sale that could be directly traced to Osborn Oldroyd’s museum, and all 10 were marked “Property of O.H. Oldroyd” in one form or another.

On June 16th I found myself in Marshalltown examining the items. I obtained my bidder number, which happened to be bidder # 1, and retreated to my hotel room to await the next day’s auction. There’s not much to do in Marshalltown, Iowa so I decided to drive to the nearby community of LeClaire, Iowa to mark time.

On June 16th I found myself in Marshalltown examining the items. I obtained my bidder number, which happened to be bidder # 1, and retreated to my hotel room to await the next day’s auction. There’s not much to do in Marshalltown, Iowa so I decided to drive to the nearby community of LeClaire, Iowa to mark time.

LeClaire rests a stone’s throw from the Mississippi River. The town is best known as the home of TV’s American Pickers. The duo’s Antique Archaeology headquarters is a converted gas station and car wash atop a small rise on the west side of the river. I pulled in about 9:30 in the morning, a half hour before they opened, and drove slowly through a crowd of some thirty people who all stopped and stared at me uncomfortably as I cruised past. I soon realized that these people were checking me out carefully to make sure I wasn’t one of “them”. The disappointment was palpable as they realized I wasn’t Frank Fritz or Mike Wolfe. I walked around the buildings, looked through the windows, and since I wasn’t in the market for a 10-foot gas station or junk car and didn’t need any American Pickers t-shirts, coffee mugs, hats, or water bottles, I headed back to Marshalltown.

The Oldroyd lots were in the middle of a 600-lot sale billed as a “Gentlemen’s Items and Silver Collector’s Auction” by the Tom Harris auction house. So I sat patiently and watched nearly 200 items (mostly an assortment of old-fashioned silver match safes) get gaveled down before my first item came up on the auction block. I won’t bore you any further with a blow-by-blow account of each item’s bidding and disposition, however, when the dust cleared, I had won 8 out of 10 Oldroyd items sold that day. Why not 10 out of 10, you ask? Well, as I am not independently wealthy, I decided it best to let 2 lots (a pair of eyeglasses with a dubious claim to fame and a cabinet photo made after Lincoln’s death) be sacrificed for the acquisition of the other 8.

Among the items I brought home were a pair of contemporaneous framed leaflets. Both are displayed starkly in black wood and glass frames, one is a copy of Lincoln’s farewell address to the citizens of Springfield, and the other is a copy of Lincoln’s favorite poem. The farewell address is important to me because Lincoln’s first stop after the delivery of this poignant edict was Indianapolis. The next item was a classic-looking photo of Lincoln ascending to heaven wrapped in the open arms of George Washington. The careworn oval metal frame fits snugly in the palm and bears the wear and patina of an item held repeatedly in the loving hands of a legion of Lincoln admirers.

Among the items I brought home were a pair of contemporaneous framed leaflets. Both are displayed starkly in black wood and glass frames, one is a copy of Lincoln’s farewell address to the citizens of Springfield, and the other is a copy of Lincoln’s favorite poem. The farewell address is important to me because Lincoln’s first stop after the delivery of this poignant edict was Indianapolis. The next item was a classic-looking photo of Lincoln ascending to heaven wrapped in the open arms of George Washington. The careworn oval metal frame fits snugly in the palm and bears the wear and patina of an item held repeatedly in the loving hands of a legion of Lincoln admirers.

The next item is the haunting life mask of Abraham Lincoln that once hung on the wall of Oldroyd’s museum. The lifesized mask is attached to a larger handcrafted oval wooden plaque with a smaller brass nameplate attached to the front. The lifemask, made by artist Leonard Volk in 1860 before Lincoln grew his signature beard, is an accurate representation of what it would have been like to look at the face of a young and vibrant Lincoln. This item was surely a highlight of the museum and, judging by the loss of paint and subsequent repair of the nose, was a good luck talisman for all visitors. Rubbing Lincoln’s nose is still a popular tradition at the Lincoln tomb in Springfield.

The next item is the haunting life mask of Abraham Lincoln that once hung on the wall of Oldroyd’s museum. The lifesized mask is attached to a larger handcrafted oval wooden plaque with a smaller brass nameplate attached to the front. The lifemask, made by artist Leonard Volk in 1860 before Lincoln grew his signature beard, is an accurate representation of what it would have been like to look at the face of a young and vibrant Lincoln. This item was surely a highlight of the museum and, judging by the loss of paint and subsequent repair of the nose, was a good luck talisman for all visitors. Rubbing Lincoln’s nose is still a popular tradition at the Lincoln tomb in Springfield.

The next item was, according to Oldroyd, the last Bible that the Lincoln family ever  owned. The Bible was obtained by Oldroyd after Mr. Lincoln was killed and presumably following the death of Mary and Tad Lincoln. The phone book-sized Bible shows signs of heavy wear and transport in compliance with the somewhat vagabond lifestyle led by Mary and Tad after vacating the White House in 1865. Mary died in 1882. Tad preceded her in 1871. The Bible includes a couple pages of contemporary Carte de Visite photographs of the Lincoln family along with a few other disparate images from the Civil War and immediate post-period. The inclusion of CDVs depicting Union Civil War Generals Grant, Sheridan, Burnside, and Sherman alongside images of the US Capitol Dome under construction and George and Martha Washington could easily be construed as Tad’s version of collecting baseball cards.

owned. The Bible was obtained by Oldroyd after Mr. Lincoln was killed and presumably following the death of Mary and Tad Lincoln. The phone book-sized Bible shows signs of heavy wear and transport in compliance with the somewhat vagabond lifestyle led by Mary and Tad after vacating the White House in 1865. Mary died in 1882. Tad preceded her in 1871. The Bible includes a couple pages of contemporary Carte de Visite photographs of the Lincoln family along with a few other disparate images from the Civil War and immediate post-period. The inclusion of CDVs depicting Union Civil War Generals Grant, Sheridan, Burnside, and Sherman alongside images of the US Capitol Dome under construction and George and Martha Washington could easily be construed as Tad’s version of collecting baseball cards.

The last three items of acquisition were perhaps the most important to me. I am a native Hoosier. I cherish the idea that Abraham Lincoln grew to manhood in the southern region of my home state. These three items offered a direct connection to Lincoln and Indiana. The first two items are innocuous in their relevance to Lincoln the Hoosier; the Lincoln family coffee grinder and Abraham Lincoln’s ice skate.

The last three items of acquisition were perhaps the most important to me. I am a native Hoosier. I cherish the idea that Abraham Lincoln grew to manhood in the southern region of my home state. These three items offered a direct connection to Lincoln and Indiana. The first two items are innocuous in their relevance to Lincoln the Hoosier; the Lincoln family coffee grinder and Abraham Lincoln’s ice skate.

The ancient-looking coffee grinder consists of a sturdy metal handle crank sprouting from the top of a wooden cabinet tower. The coffee maker’s tower was likely constructed by Abraham Lincoln’s father Thomas, a carpenter by trade. Hidden at the foot of the cabinet is a small drawer designed to catch the ground-up remains of coffee beans. The Lincoln homestead in Spencer County was part of the western frontier when the family arrived in 1816. Many diaries and letters confirm the importance of coffee to Western pioneers. In his diary, Josiah Gregg, a frontier trapper, wrote about the pioneers’ love of coffee. “The insatiable appetite acquired by travelers upon the Prairies is almost incredible, and the quantity of coffee drank is still more so,” he wrote. “It is an unfailing and apparently indispensable beverage, served at every meal.” This innocent-looking household appliance would have been one of the most cherished articles owned by the Lincoln family as young Abe grew up.

The next Indiana Lincoln item is an ice skate. The thick wooden shoe stand is shaped like an hourglass and the heavy iron blade is curled at each end like an ancient Crakow shoe. While no official reference exists of Lincoln the ice skater, the skate presents a romantic image of boyhood Lincoln at play on a frozen southern Indiana pond. Simply holding it in your hands brings a smile to your face.

The next Indiana Lincoln item is an ice skate. The thick wooden shoe stand is shaped like an hourglass and the heavy iron blade is curled at each end like an ancient Crakow shoe. While no official reference exists of Lincoln the ice skater, the skate presents a romantic image of boyhood Lincoln at play on a frozen southern Indiana pond. Simply holding it in your hands brings a smile to your face.

The last item I purchased was the one I had resolved was heading back home to Indiana  with me, at all costs. It is an ancient-looking Colonial Era metal candle maker. During colonial times up to the Antebellum Era, candles were the main source of light during the long, dark, nighttime hours. Candles on the western frontier were made from beeswax and tallow (animal fat). The wicks were lain loosely inside the tube as the wax was poured in around them to harden.

with me, at all costs. It is an ancient-looking Colonial Era metal candle maker. During colonial times up to the Antebellum Era, candles were the main source of light during the long, dark, nighttime hours. Candles on the western frontier were made from beeswax and tallow (animal fat). The wicks were lain loosely inside the tube as the wax was poured in around them to harden.

Included with the candle maker is a framed certificate written and signed by Osborn Oldroyd reading: “This candle maker is from the Lincoln and Sparrow Cabin on Pigeon Creek Indiana (1818-1835) O.H. Oldroyd Washington April 9, 1901”. The certificate has a small brass diecut tab attached with the seal of the state of Indiana inset. It would be hard to find a more romantic artifact to illustrate Lincoln’s time spent in the Hoosier state. Young Abraham may well have learned to read by the light of a candle made in this, the Lincoln family candle mold. Stories abound of Young Abe the railsplitter reading by candle and firelight into the wee hours of the morning after a long day’s work in the fields.

Included with the candle maker is a framed certificate written and signed by Osborn Oldroyd reading: “This candle maker is from the Lincoln and Sparrow Cabin on Pigeon Creek Indiana (1818-1835) O.H. Oldroyd Washington April 9, 1901”. The certificate has a small brass diecut tab attached with the seal of the state of Indiana inset. It would be hard to find a more romantic artifact to illustrate Lincoln’s time spent in the Hoosier state. Young Abraham may well have learned to read by the light of a candle made in this, the Lincoln family candle mold. Stories abound of Young Abe the railsplitter reading by candle and firelight into the wee hours of the morning after a long day’s work in the fields.

The reference by Oldroyd to the “Lincoln-Sparrow” cabin is an obscure one, recognized by only the most astute Lincoln scholar. Elizabeth and Thomas Sparrow (Nancy’s maternal aunt and uncle), moved in with the Lincoln family at Pigeon (or Pidgin) Creek in 1817 a year before Captain Oldroyd’s certificate denotes. The Lincolns had just finished their cabin and moved out of their 3-sided lean-to, later known as the “half-faced camp”. The Sparrows were given the lean-to to live in while they built their cabin. Shortly after the Sparrows arrived, Nancy bought six milk cows to provide milk for the two families. In the fall of 1818, an illness known as “the milk-sick” swept the area. People at Pigeon Creek were dying from drinking milk. To be safe the Lincolns and Sparrows kept the children from drinking milk. However, the adults of both families drank it for almost two years before becoming sick. Lincoln’s “Angel Mother” and the Sparrows all died of the milk sickness. 9-year-old Abraham Lincoln never really got over the childhood loss.

So now you can see why these items were so important for me to bring back to Indiana. They belong here. Ironically, two days after I returned from my Iowa Oldroyd journey, I was visited in my home by WISH-TV 8 reporter Dick Wolfsie. Dick was on a visit to film a segment (which as of this writing has not aired) for a Saturday morning broadcast about collectors and their collections. The items were so new to me that they remained spread out on the kitchen counter with the original auction lot number tags attached.

Like me, Mr. Wolfsie was excited to handle the items. He was drawn in particular to the Lincoln Family Bible which was featured prominently in the segments. He was also drawn to the Lincoln ice skate. How could anyone not be drawn to Abe Lincoln’s ice skate? Dick’s only question was “Where is the other one?” The segments will air soon and can be viewed by going to Dick Wolfsie’s Channel 8 webpage and clicking on his profile and segment list.

A few days later, I received a phone call from representatives of the American Pickers crew. Seems that Frank and Mike were on their way to Indiana in search of stories and things to buy. I informed them that while I certainly had stories to share, I had nothing to sell. We took a mutual pass.

Lastly, my wife treated me to a birthday trip to Springfield, Illinois in July. I traveled to the Lincoln home on an early Saturday morning to reflect while seated in front of the Lincoln home. Based on trips past, I’ve learned that the early morning hours are best. No school buses, tourists or fitness walkers/bikers to mar the scene. I have been coming to Springfield for many years. Of course, Abraham Lincoln is the reason for my visit. However, I never forget that Osborn Oldroyd lived in the house and operated his museum here for nearly a decade (1884-93). I’d asked several people, ranging from officials at the Lincoln Museum to parks department employees, about Oldroyd in the past but always got a cool reception to my querie.

Lastly, my wife treated me to a birthday trip to Springfield, Illinois in July. I traveled to the Lincoln home on an early Saturday morning to reflect while seated in front of the Lincoln home. Based on trips past, I’ve learned that the early morning hours are best. No school buses, tourists or fitness walkers/bikers to mar the scene. I have been coming to Springfield for many years. Of course, Abraham Lincoln is the reason for my visit. However, I never forget that Osborn Oldroyd lived in the house and operated his museum here for nearly a decade (1884-93). I’d asked several people, ranging from officials at the Lincoln Museum to parks department employees, about Oldroyd in the past but always got a cool reception to my querie.

On this latest visit, I wandered over to the interpretive marker directly across the street and facing the Lincoln home. Much to my amazement, there he was. The newly placed plaque is dedicated to Osborn Oldroyd’s museum once housed there. I could not believe my eyes! At last, Oldroyd has received official recognition from the powers that be in Lincoln’s Springfield. Maybe things are looking up for Captain Oldroyd after all. I doubt that I’ll ever be prouder of a historical pursuit than I was that morning.

Osborn Oldroyd-Keeper of the Lincoln flame. Part III

Original publish date: July 20, 2017

Original publish date: July 20, 2017

In the past two columns, I’ve introduced you to Osborn Oldroyd, king of all Lincoln collectors. Over the years, I have chased Oldroyd from Springfield, Illinois to Washington D.C. to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, and most recently to Marshalltown, Iowa. In Gettysburg, I purchased a collection of Oldroyd memorabilia assembled over two decades by a former Abraham Lincoln impersonator named Bill Ciampa. The collection of over 300 items included photos, postcards, books, literature, brochures, business cards, certificates, and even a paperweight. But the bulk of the assemblage consisted of letters written to Oldroyd spanning the time he spent living in the Lincoln family home in Springfield to his move to the “House Where Lincoln died” across the street from Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C.

Granted, the letters were a bit picked over by the time they landed in my lap. Gone were the letters from the big names associated with the life and death of Abraham Lincoln that Oldroyd quoted in his many books about our sixteenth President. There was no U.S. Grant, Andrew Johnson, Mary Lincoln, Winfield Hancock or George Meade, although Oldroyd was known to have corresponded with all of them. But there were a couple famous, albeit obscure, personalities from the Lincoln Era that remained. I recognized a letter from suffragette and women’s Temperance leader Frances Willard, as well as another from T.M. Harris, a Brigadier General who served on the Lincoln Conspirators trial in Washington, D.C. Harris, wrote the forward to one of Oldroyd’s books.

There was a fascinating letter from Ferdinand Petersen, son of the owner of the House where Lincoln died, who was present the night Lincoln was assassinated. The letter was written in October of 1913 by Ferdinand to Oldroyd in an effort to clear up several myths that had plagued his family for years about that tragic night. “It makes me tired as the youngest man living of the very few left who were there at the time…I own and still have the pillowcases on which President Abraham Lincoln died and I have mostly all of the pictures that were in the room at the time and…I do not wish to sell them to the Government either nor any relic I have…Someday I’ll hand them over to the government for preservation.” Ferdinand also makes it a point to dispel the rumor that the Petersen house was ever a rooming house, “it was a home”.

Another of the letters, dated Dec. 10, 1902, touched me personally because it was written by the sister of Louis Weichmann, the main government witness at the trial of the conspirators. Weichmann lived in Mrs. Surratt’s boarding house and many believe it was Weichmann’s testimony that got Mary Surratt hung. Weichmann moved to Anderson Indiana after the trial and founded Anderson business college. He is buried in Anderson’s St. Francis cemetery in an unmarked grave. “Dear Sir-I am sending you a copy of Sunday’s Indianapolis Journal containing a confession of one of the conspirators of President Lincoln….With best regards from our family, I remain Sincerely yours, Mrs. C.O. Crowley Sister of the late L.J. Wiechmann.” Curiously, Mrs. Crowley misspelled her own maiden name in her letter.

Another of the letters, dated Dec. 10, 1902, touched me personally because it was written by the sister of Louis Weichmann, the main government witness at the trial of the conspirators. Weichmann lived in Mrs. Surratt’s boarding house and many believe it was Weichmann’s testimony that got Mary Surratt hung. Weichmann moved to Anderson Indiana after the trial and founded Anderson business college. He is buried in Anderson’s St. Francis cemetery in an unmarked grave. “Dear Sir-I am sending you a copy of Sunday’s Indianapolis Journal containing a confession of one of the conspirators of President Lincoln….With best regards from our family, I remain Sincerely yours, Mrs. C.O. Crowley Sister of the late L.J. Wiechmann.” Curiously, Mrs. Crowley misspelled her own maiden name in her letter.

There is an amusing letter dated April 9, 1906, from Teddy Roosevelt’s Secretary of the Treasury to Oldroyd: “It is requested that the flag in which J. Wilkes Booth caught his spur, and which was loaned to you for temporary use in the house in which President Lincoln died, be delivered to the bearer for return to the Treasury Department.” It’s easy to imagine Oldroyd’s dismay at the prospect of returning such an important artifact from his museum. More so, it implies that this may not have been the first request for return.

However, it was the letters from common, everyday people that proved to be the most fascinating. The letters began in 1869 while Osborn was just an average autograph seeker and continued through to 1929 after Oldroyd sold his collection to the US Government and just months before he died in 1930. Several of the letters are from prospective customers wishing to obtain a copy of one of Oldroyd’s many books or souvenirs about Lincoln. Many of the letters were sent by visitors to his Lincoln Museum. They extol the hearty virtues of Oldroyd’s collection and his superior tour guide skills. (Funny, most of these are from women leading me to believe that Captain Oldroyd was an unashamed flirt.) Still more are from folks wishing to send Oldroyd some cherished family Lincoln memento for display in his museum. All of the letters offer a fascinating glimpse into the life of Osborn Oldroyd.

Two of the letters hail from the Hoosier state. One written in 1929 from L.N. Hines, President of Indiana State Teachers College (modern-day ISU in Terre Haute): “I always remember my wonderful visit with you a year ago last February. I hope that I may be fortunate enough to come your way again before long.” and the other from a man in Larwill, Indiana written in 1926: “We have in our possession (sic) a campaign button of Lincoln & Hamlin. Would you care to have it among your other relics? Resp. Burton R. White”

The others, well, they’re from all over. They address Oldroyd variously as Colonel, Uncle, Cousin, Father, or Captain. A Boston lawyer writes: “I send you, herewith, a ticket of admission to the ‘Green Room’ (at the White House) on the occasion of President Lincoln’s funeral, April 19, 1865.” A York, Pennsylvania museum curator writes: “We have…a wooden short sword made out of the table that ‘Peanut Johnny’ used in front of Ford’s Theatre the night Lincoln was shot. It was ‘Johnny’ who held Booth’s horse.”

A Chicago businessman writes, “I want you to know how keenly I appreciate the kindness and courtesy which you showed me while in your museum. I count the hours spent there and with you, as the most pleasent (sic) and profitable ones of my weeks visit to our capitol.” A famous Washington DC female lawyer writes, “I have a friend who is in limited circumstances who has a very small lock of President Lincoln’s hair-which she wishes to dispose of-It occurs to me that you must know persons interested in Lincoln relics who might like to purchase this. It was given to Miss Gardner’s father Alexander Gardner, photographer to the Army of the Potomac by the undertaker who prepared Lincoln’s body for burial.”

Over the past several years, I feel like I’ve traveled in the footsteps of Oldroyd many times. I’ve experienced his highs and his lows. I’ve struggled alongside him as he labored to gain legitimacy for what Abraham Lincoln’s son Robert referred to as “Oldroyd’s Traps”. I agonized with his quest to sell his priceless collection to the United States Government (far below value) that took years to finalize. I think I understand him better now and, after three articles, you should too.

I think my feelings may best be summed up in a letter found in the collection that has become one of my favorites: “Washington, D.C. May 2, 1926. Dear Father Oldroyd: Accept hearty congratulations! I am glad I have lived to see your long years of effort rewarded, and your dream of sixty-three years come true. Very Sincerely, Kathie.” That letter sums it all up for me. Besides, my mother-in-law’s name is Kathie and I kinda like her too.

In the few years that have passed since I first wrote this series, a few things have changed. I have continued my pursuit of all things Oldroyd by picking up a few things here and there. I spent a weekend at the Lilly Library (on the campus of Indiana University in Bloomington) to examine a small group of letters and documents written by, or belonging to, Osborn Oldroyd. The library was created in the late 1950s by Josiah Kirby “Joe” Lilly Jr. (1893 – 1966) grandson of Pharmaceutical magnate Eli Lilly. The Lilly Library, named in honor of the family, houses the university’s rare book and manuscript collections.

Lilly was a prolific collector of rare books and Indiana historical memorabilia. His collection included a First Folio of the works of William Shakespeare, a Gutenberg Bible, a double-elephant folio of John James Audubon’s Birds of America, the first printing of the American Declaration of Independence (the Dunlap Broadside), and a first edition of Edgar Allan Poe’s Tamerlane. Lilly’s gold coin collection is in the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C. In a November 26, 1954 letter to I.U. President Herman B Wells, Lilly outlined his intention to donate the bulk of his collection to the university. IU announced the donation, which the New York Times estimated at over $5 million, on January 8, 1956. Lilly’s donation eventually totaled over 20,000 books and 17,000 manuscripts, including over 350 oil paintings and prints.

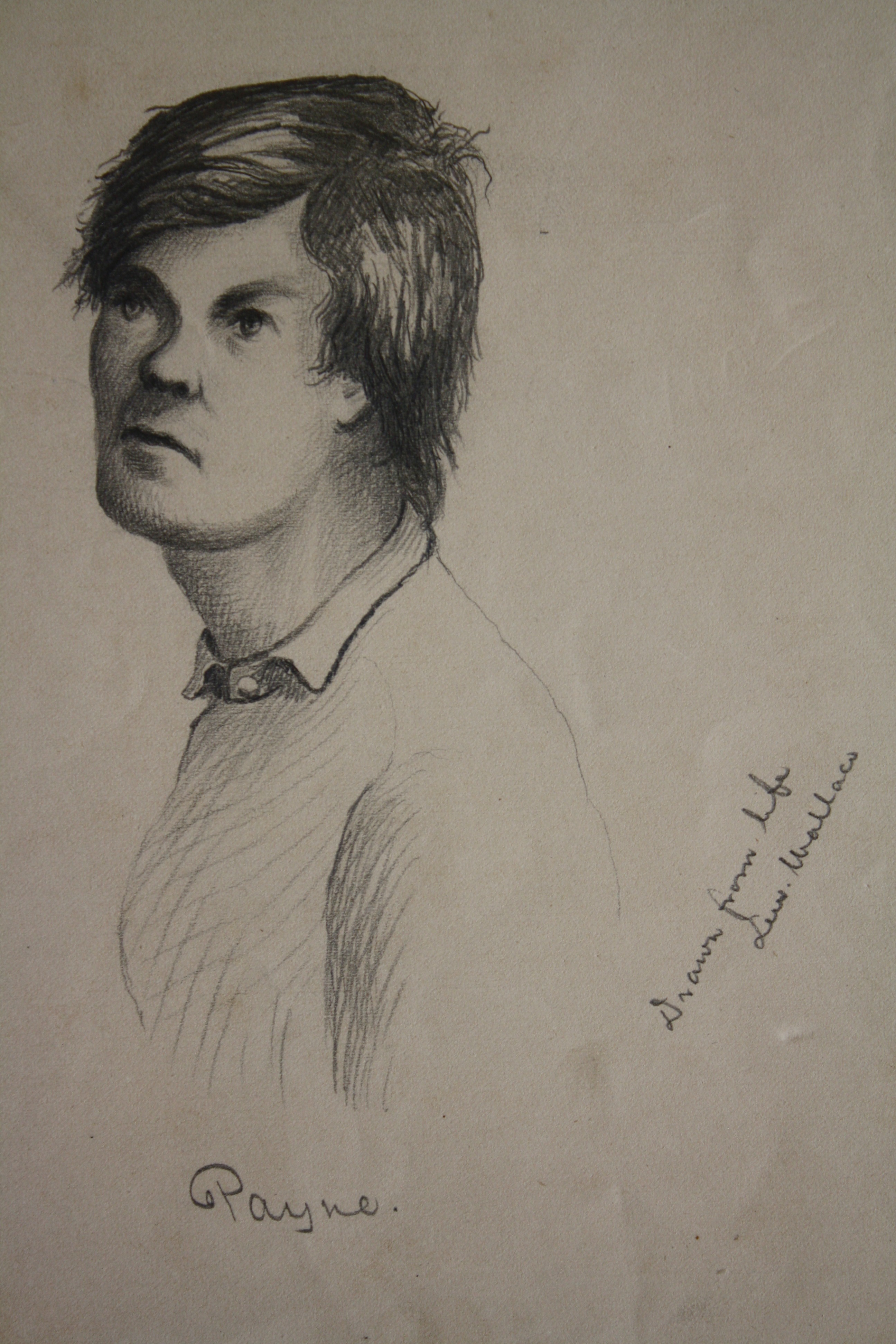

Included within that collection was a group of several dozen items that once belonged to Osborn Oldroyd himself. This included correspondence from Anderson’s Louis Weichmann to Oldroyd about shared information for books about Abraham Lincoln both men were simultaneously working on as well as photos and several handwritten eyewitness accounts of the assassination of President Lincoln. My personal favorite was a pencil drawing of Lincoln Conspirator Lewis Thornton Powell drawn by Crawfordsville, Indiana’s General Lew Wallace.

Included within that collection was a group of several dozen items that once belonged to Osborn Oldroyd himself. This included correspondence from Anderson’s Louis Weichmann to Oldroyd about shared information for books about Abraham Lincoln both men were simultaneously working on as well as photos and several handwritten eyewitness accounts of the assassination of President Lincoln. My personal favorite was a pencil drawing of Lincoln Conspirator Lewis Thornton Powell drawn by Crawfordsville, Indiana’s General Lew Wallace.

While most people recall General Wallace as the author of Ben Hur, many forget that he had other claims to fame including nearly single-handedly saving Washington DC from capture by Rebel General Jubal Early’s troops at the Battle of Monocacy in 1864. He would later be appointed Governor of the New Mexico territory during Billy the Kid’s exploits and also served as a member of the Lincoln assassination conspirator’s trials. General Wallace made the drawing of Powell during the trial while sitting just a few feet away from the man who nearly killed Secretary of State William Seward. Powell would be hanged for his crime. No doubt this single item is the reason these particular Oldroyd items ended up at the Lilly Library.

What I came away from, after my Springtime visit to IU’s Lilly Library, was an even deeper understanding of the passion that must have driven Osborn Oldroyd’s pursuit of Lincoln Memorabilia. It became easy to understand the euphoria that surely overcame Oldroyd as he received, opened, and read these personal accounts written by people connected to Mr. Lincoln. Viewing these priceless relics also reinforced the value of Osborn Oldroyd’s obsession. For without them, precious details and specific memories of historic events would have been lost forever. And thanks to Mr. Lilly, these particular objects are henceforth and forever available for viewing by all Hoosiers at the Lilly Library in B-town. Little did I know that this Springtime visit to my alma mater was just the beginning of a journey that would occupy the next month of my life.

Next week: part IV of “Osborn Oldroyd-Keeper of the Lincoln Flame.”