Tag: Osborn H. Oldroyd

Osborn H. Oldroyd’s Greatest Fear.

Original Publish Date March 6, 2025.

https://weeklyview.net/2025/03/06/osborn-h-oldroyds-greatest-fear/

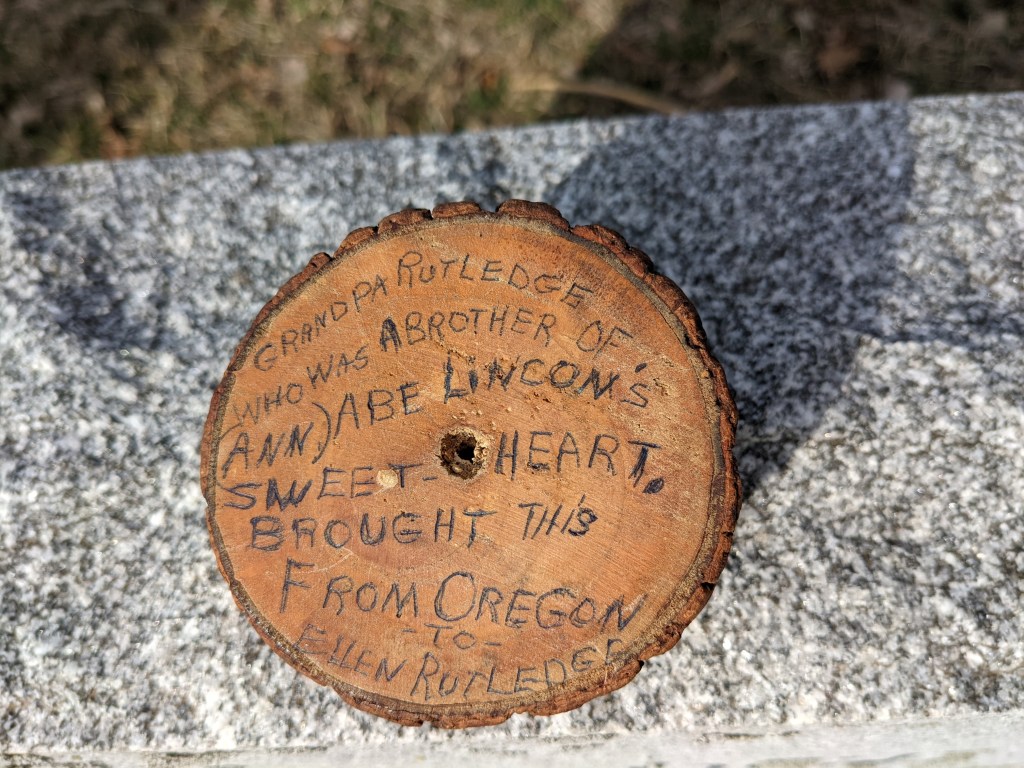

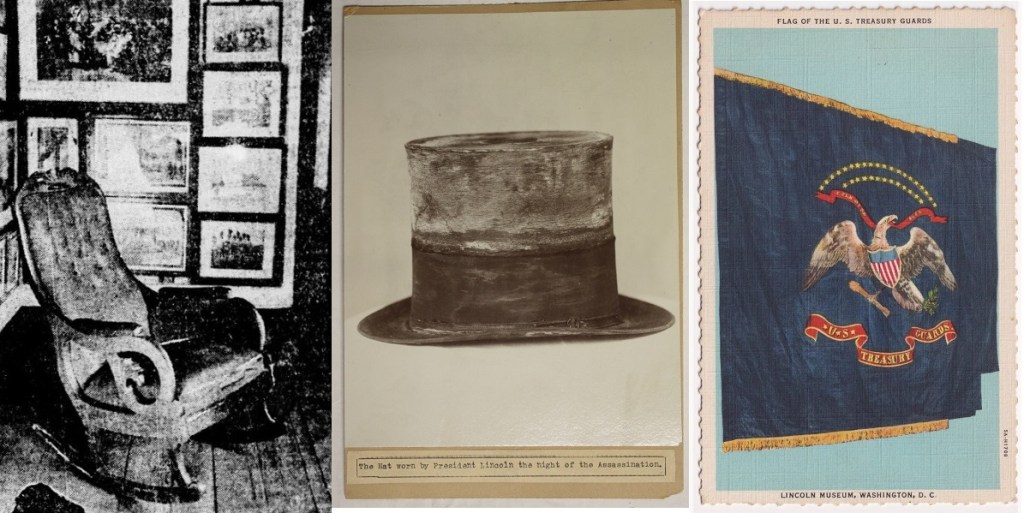

My wife and I recently traveled to Springfield, Illinois for a book release event (actually two books). One book on Springfield’s greatest living Lincoln historian, Dr. Wayne C. “Doc” Temple, and the other on my muse for the past fifteen years, Osborn H. Oldroyd. I have fairly worn out my family, friends, and readers with the exploits of Oldroyd over the years. He has been the subject of two of my books and a bevy of my articles. Oldroyd was the first great Lincoln collector. He exhibited his collection in Lincoln’s Springfield home and then in the House Where Lincoln Died in Washington DC from 1883 to 1926. Oldroyd’s collection survives and forms much of the objects in Ford’s Theatre today.

For this trip, we traveled up from the south to Springfield through parts of northwest Kentucky and southeast Missouri. What struck us most were the conditions of the small towns we drove through. Today many of these little burgs and boroughs are in sad shape, littered by once majestic brick buildings featuring the names of the merchants that built them above the doorways, eaves, and peaks of their frontispieces in a valiant last stand. Most had boarded-up windows and doors and some with ghost signs of products and services that disappeared generations ago.

They are tightly packed and many share common walls. We were amazed how many of them have caved-in or worse, burnt down. The caved-in buildings are the work of Father Time and Mother Nature, but the burnt ones look as if the fires were extinguished just recently. My wife deduces that these are likely the result of the many meth labs that blight these long-forgotten, empty buildings. Indeed, a little research reveals that these rural areas do lead the league in these hastily constructed, outlaw drug factories.

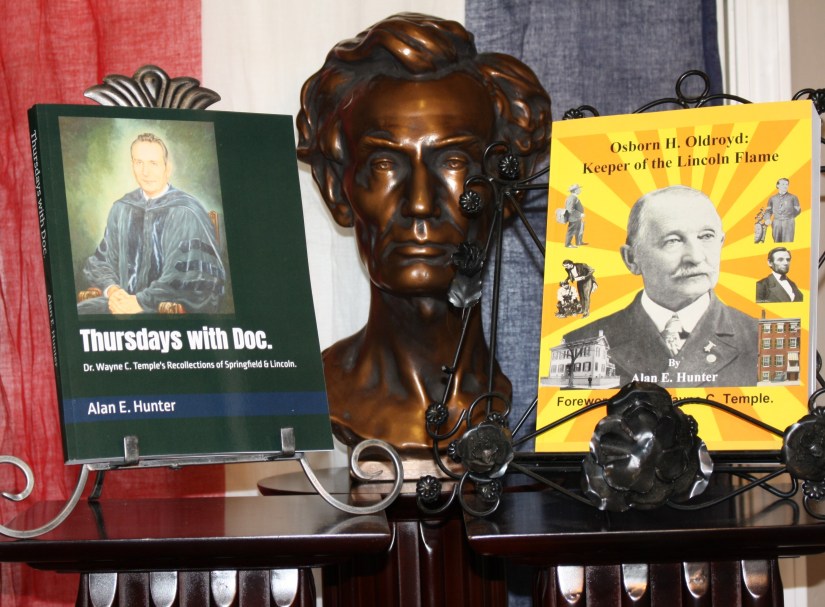

Of course, that got me thinking about Oldroyd’s museum. Oldroyd lobbied for decades to have his collection purchased by the U.S. government and preserved for future generations to explore. The Feds eventually purchased it in 1926 for $50,000 (around $900,000 today). For over half a century while assembling his collection, Oldroyd had one great fear: Fire. Visiting the House Where Lincoln Died today, the building remains unique in size and architecture compared to those around it. In Oldroyd’s day, smoking cigars, pipes, and cigarettes indoors was as prevalent as carrying cell phones and water bottles are today. The threat of fire was very real for Oldroyd.

The March 20, 1903, Huntington Indiana Weekly Herald ran an article titled “A Visit to the Lincoln Museum in Washington City.” After describing the relics in the collection, columnist H.S. Butler states, “It is hoped the next Congress will purchase this collection and care for it. Mr. Oldroyd is not a man of means such as would enable him to do all he would like, and it seems to me a little short of criminal to expose such valuable relics, impossible to replace, to the great risk of fire. I understand Congressman [Charles] Landis, of Indiana, is trying to get the collection stored in the new Congressional Library, in itself the handsomest structure, interiorly, in Washington. I hope that his brother, the congressman from the Eleventh District [Frederick Landis], will lend his influence to Senators [Charles] Fairbanks and [Albert] Beveridge to urge forward the same end.”

Fifteen years later, the Topeka State Journal described an event that fueled Oldroyd’s concern. “May 21 [1918]-a few days ago the Negro cook in the kitchen of a dairy lunch spilled some fat on the fire and the resulting blaze was extinguished with some difficulty. The unique feature of this trifling accident was that, had the blaze gotten beyond control, it would probably have destroyed a neighboring house in which is the greatest collection in the world of relics, manuscripts, and books bearing upon the life and death of Abraham Lincoln…Sixty feet away from the room in which Lincoln died are three kitchens of restaurants and a hotel. More than one recent fire scare has caused alarm over the danger that threatens these relics.”

The February 11, 1922, Dearborn [Michigan] Independent reported, “A vagrant spark, a carelessly tossed cigarette or cigar stub, an exposed electric wire might at any time mean the destruction of the collection and the building which, of course, is itself a sacred bit of Lincolniana.” The January 21, 1924, Daily Advocate of Belleville, Ill. reported “The collection is contained in a small and overcrowded room of the house opposite Ford’s Theatre, with two restaurants across a narrow alleyway constituting a constant fire menace…it is likely that the U.S. Government will request that the Illinois Historical Society return the bed in which Lincoln died, that it may again be placed in the room it occupied on that fateful night and the entire setting restored.” Due to that unresolved fire threat the bed was never returned and is today on display at the Chicago History Museum. A 1924 Christmas day article in the Washington Standard 1924 described, “There are a number of restaurants in the block at the rear, and once an oil supply house did business close at hand. On two occasions there have been fires in the neighborhood.”

The July 6, 1926, Indianapolis News speculated, “The government will add to the collection the high silk hat Lincoln wore to the theatre that fatal night, the chair in which he sat in the presidential box, and the flag in which Booth’s foot caught. The flag now hangs in the treasury, while the hat and chair are in storage. These articles formerly were in the Oldroyd collection, but after a fire in the neighborhood some years ago, officials of the government took them back, fearing that they might be destroyed.” The February 18, 1927, Greenfield [Indiana] Reporter stated, “The plan proposed by Senator Watson, of Indiana, and Rep. Rathbone of Illinois, is to remodel the building to protect it against the danger of fire and the ravages of age. They would…place in it the famous Oldroyd collection of Lincoln relics.” Fire remained a nightmare for Oldroyd right up to the day he died on October 8, 1930.

Ironically, after that book signing I found myself browsing the bookstore. I found there a 2 1/2” x 4” business card from the New Lincoln Cafe in the adjoining building to the north of Oldroyd’s Museum (at 516 10th St. NW). Putting aside the fact that I have a personal affinity for old business cards, the item called out to me and made me wonder about the businesses that had been neighbors to this hallowed spot over the generations.

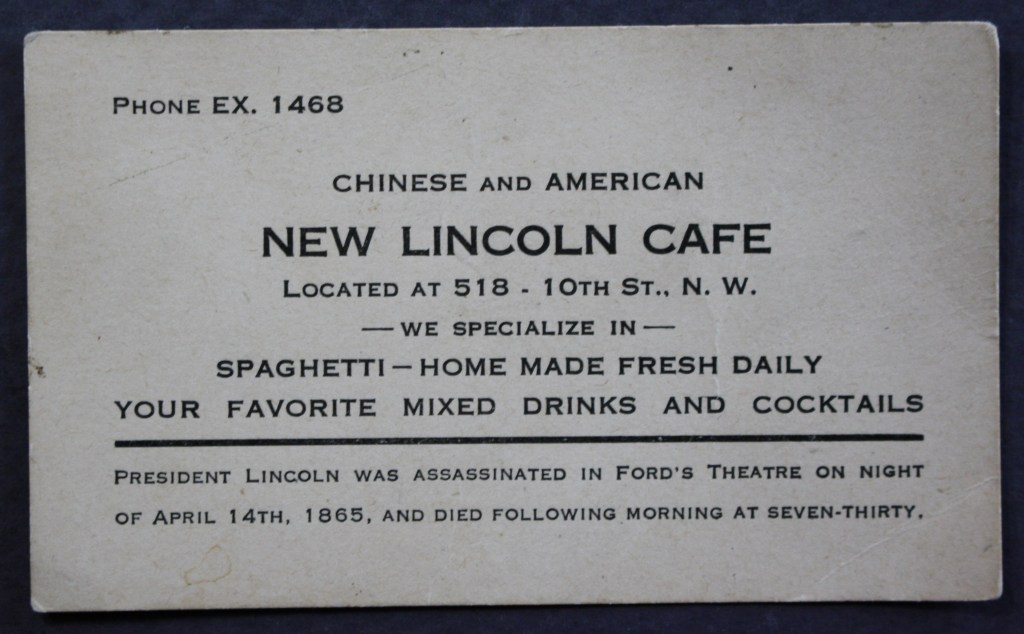

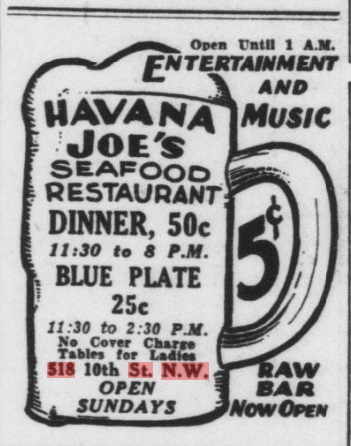

The card reads: “Chinese and American New Lincoln Cafe. Located at 518 10th St., N.W. Phone EX. 1468. We Specialize In Spaghetti-Home Made Fresh Daily. Your Favorite Mixed Drinks And Cocktails. President Lincoln Was Assassinated In Ford’s Theatre On Night Of April 14th, 1865, And Died Following Morning At Seven-Thirty.” A check of the records indicates that this restaurant remained next to the museum from the late 1930s to the early 1960s. This was just one of the businesses to call that space home over the generations.

Located in the Penn Quarter section of DC, the building was built sometime between 1865 to 1873. It envelopes the entire north side and part of the northwest back of the HWLD. It is 4 stories tall and features 11,904 square feet of retail space. One of the earliest storefronts to appear there was Dundore’s Employment Bureau which served D.C. during the 1870-90s. Ironically, when Dundore’s moved three blocks south to 717 M Street NW, the agency regularly advertised jobs at businesses occupying their old address for generations to come. Above the Dundore agency was Mrs. A. Whiting’s Millinery, which created specialty hats for women. The Washington Evening Star touted Mrs. Whiting’s “Millinery Steam Dyeing and Scouring” business for their “Imported Hats and Bonnets”. A 3rd-floor hand-painted sign on the bricks of the building advertising Whiting’s remained for years after the business vacated the premises, creating a “ghost sign” visible for many years as it slowly faded from view.

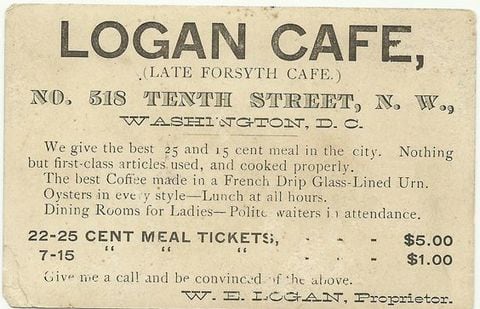

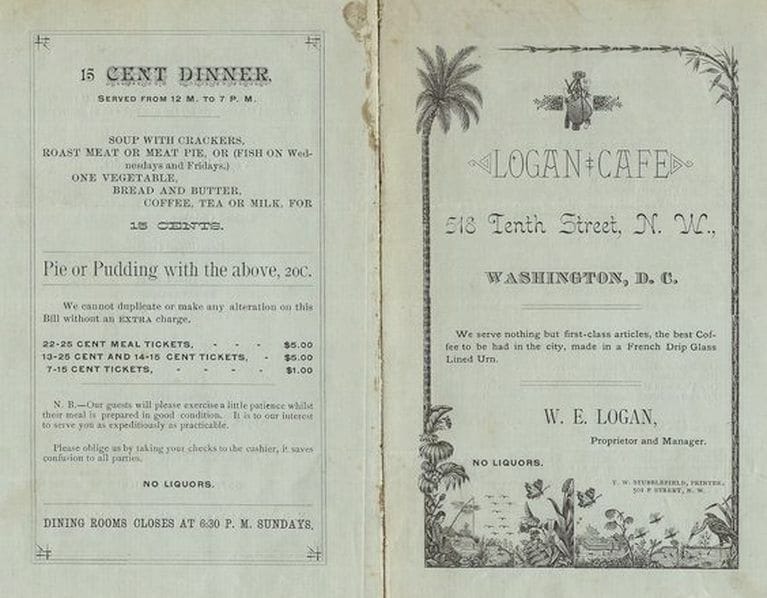

The Forsyth Cafe seems to have been the first bistro to pop up next to the Oldroyd Museum. In late February/March 1885 (in the leadup to Grover Cleveland’s first Presidential Inauguration), DC’s Critic and Record newspaper’s ad for the cafe decries, “Yes, One Dollar is cheap for the Inauguration supper, but what about those excellent meals at the Forsythe Cafe for 15 Cents?” The Forsyth continued to advertise their meals from 15 to 50 cents but by late 1886, they were gone, replaced by the Logan Cafe. The Logan offered 15 and 25-cent breakfasts, “Big” 10-cent lunches, and elaborate 4-course dinners of Roast beef, stuffed veal, lamb stew, & oysters. Proprietor W.E. Logan’s claim to fame was “the best coffee to be had in the city, made in French-drip Glass-Lined Urn” and “Special Dining Rooms for Ladies-Polite waiters in attendance” and his menus warned “No Liquors” served.

The June 4, 1887, Critic and Record reported on a “friendly scuffle” at the Logan between two “colored” employees when cook Charles Sail tripped waiter William Butler who hit his head on the edge of a table and died the next morning at Freedman’s Hospital. The men were described as best friends and the death was deemed an accident. By late 1887, the Logan disappears from the newspapers. From 1897 to 1897, the building was home to the Yale Laundry. The Jan. 7, 1897, DC Times Herald reported on an event that likely added to Oldroyd’s anxiety. The article, titled “Laundry is Looted” details a break-in next door to the museum during which a couple of safecrackers got away with $85 cash including an 1883 $5 gold piece.

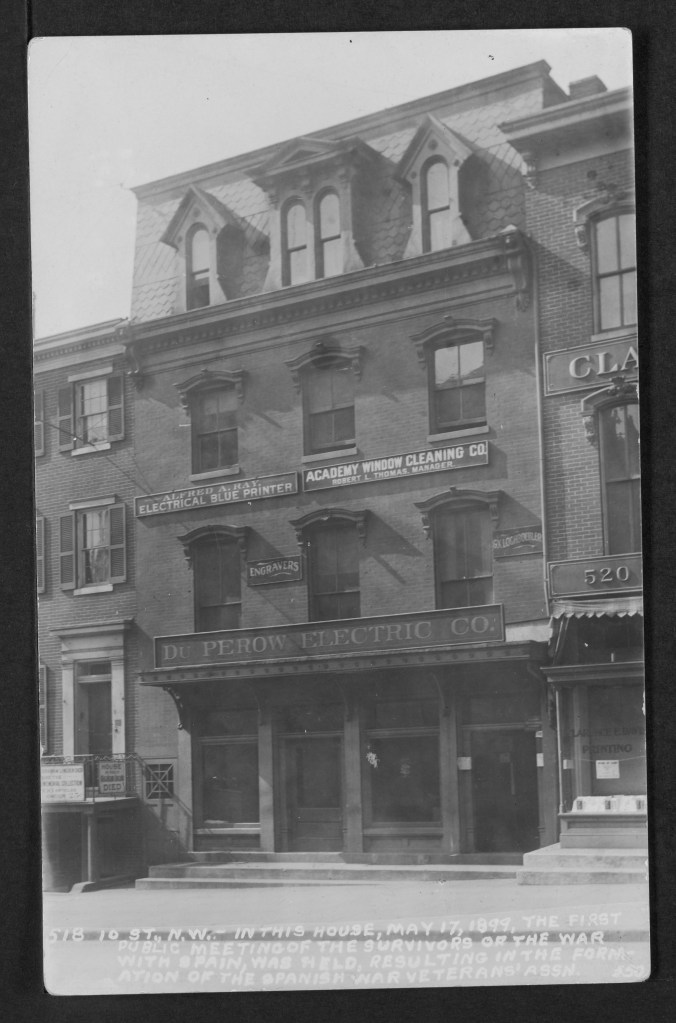

A real photo postcard in the collection of the District of Columbia Public Library pictures the building during Yale Laundry’s tenure captioned, “In this house the first public meeting of the survivors of the war with Spain, was held on May 17, 1899, resulting in the formation of the Spanish War Veterans’ Association.” The Dec. 1, 1900, Washington Star notes the addition of Harry Clemons Miller’s “Teacher of Piano” Studio and by 1903, the “Yale Steam Laundry” appeared in the DC newspapers at the address.

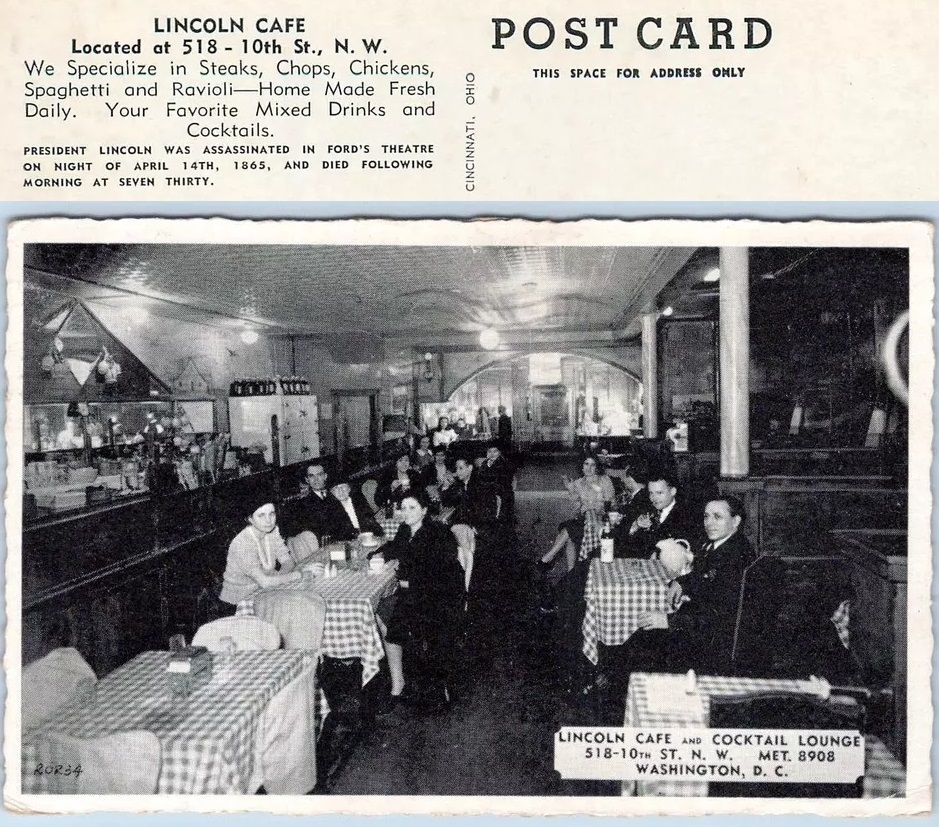

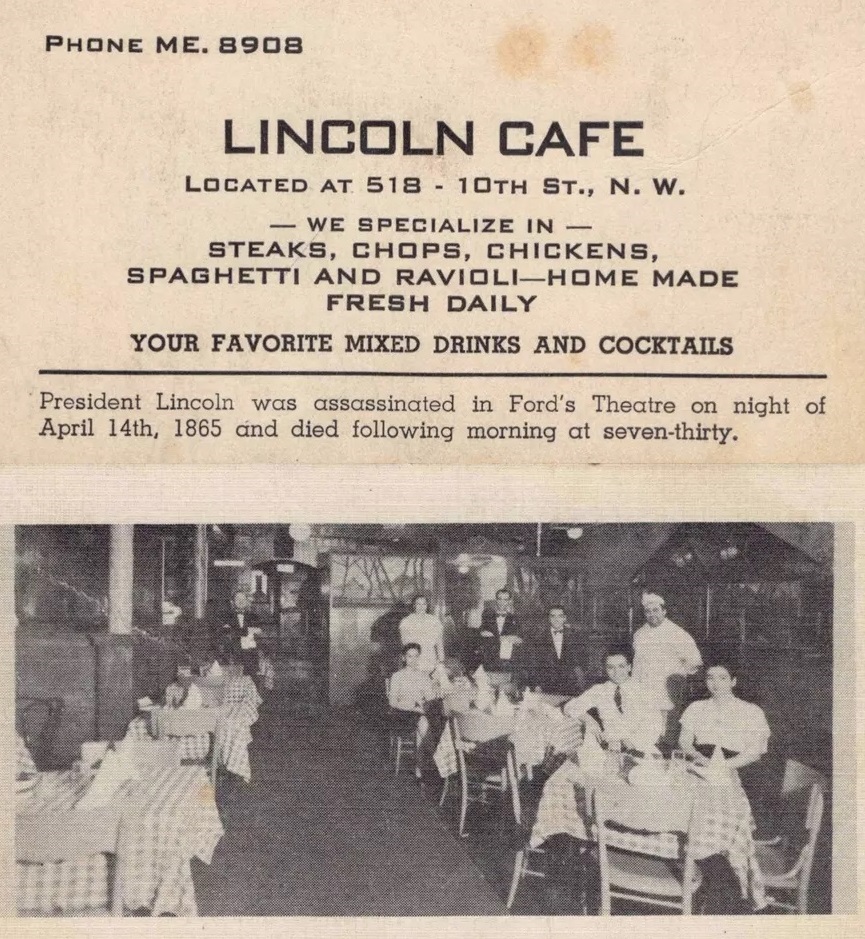

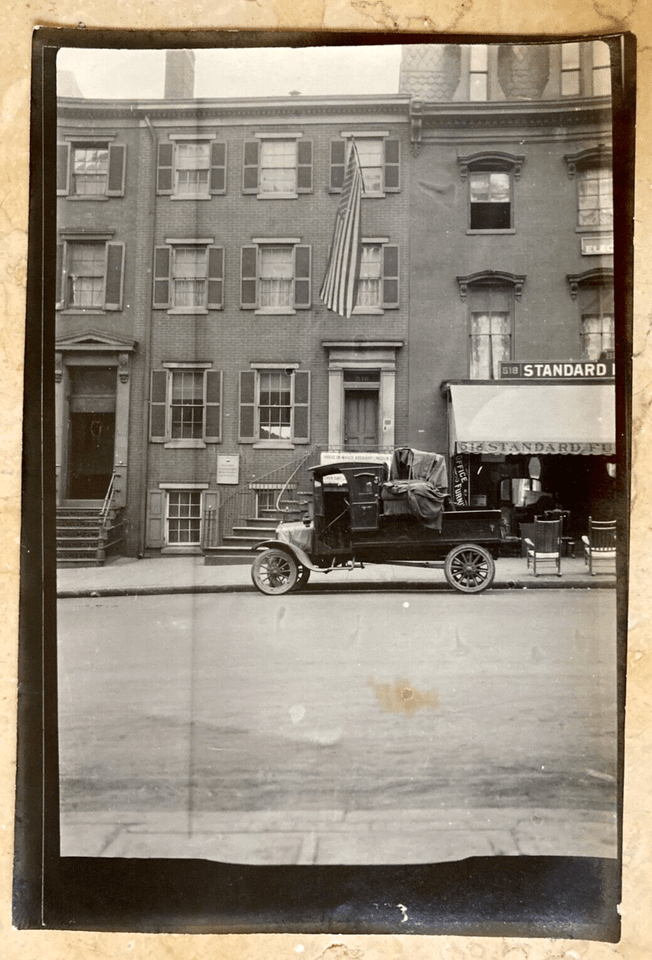

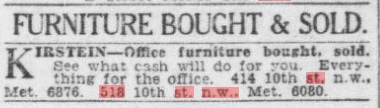

In 1909, Du Perow Electric Co. (AKA as “Du Pe”) and partner Alfred A. Ray “Electrical Blueprints” occupied the building. A window cleaning company occupied room # 9 and a leather goods store was located there during this same period. By 1912, the storefront was occupied by the Standard Furniture Co. At least one photo survives presenting an amusing scene of a furniture truck blocking the entrance to Oldroyd’s museum. Amusing to the viewer today but most assuredly not to the museum curator back in the day. Eventually, the restaurants, bars, and cafes that worried Oldroyd began to come and go, among them, the Lincoln Cafe & Cocktail Lounge, whose sign was dominated by the words “Beer Wine.” It appears that during the 1920-50s, a Pontiac, DeSoto, Plymouth Motor Car dealer known as “News & Company” kept an office in the building, with the car lot and gas station across the street.

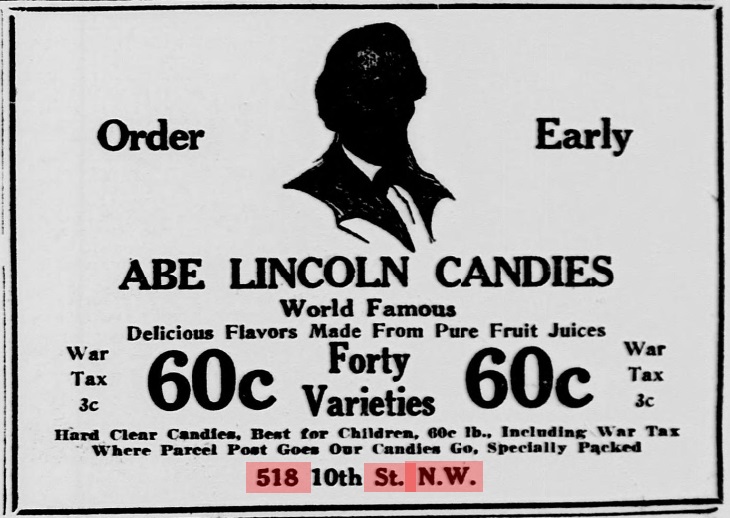

Old-timers remember a long-term tenant known as “Abe Lincoln Candies” that occupied the space from the 1950-70s. Other recent tenants included Abe’s Cafe & Gift Shop, Bistro d’Oc and Wine Bar, Jemal’s 10th Street Bistro, Mike Baker’s 10th St Grill, and the I Love DC gift store, and last year, The Inauguration-Make America Great Again Store, who one Yelp reviewer complained was crowded with outdated, sketchy clothing and that “they make u give them a good review before they give u a refund kinda scummy.”

As for the building on the opposite side of Oldroyd’s museum at 514 Tenth St. NW, it remained a residence until 1922 when a $55,000, 10-story concrete & steel building with steam heat and a flat slag roof was built. Designed by architect Charles Gregg and built by Joseph Gant, the sky-scraper, known as the Lincoln Building, dwarfed the Oldroyd Museum. It was home to several businesses, including the Electrical Center (selling General Electric TVs, radios, and appliances) and the Garrison Toy & Novelty Co, its modern construction alleviated any concern of fire.

It must be noted that many great collections of Lincolniana fell victim to fire in the century and a half after Lincoln’s death. The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 consumed many Lincoln objects, documents, and personal furniture that had been removed from the Springfield home after the President’s departure to Washington DC. On June 15, 1906, Major William Harrison Lambert (1842-1912), recipient of the Congressional Medal of Honor and one of the Lincoln “Big Five” collectors, lost much of his collection in a fire at his West Johnson St. home in Germantown, Pa. Among the items lost were a bookcase, table, and chair from Lincoln’s Springfield law office and the chairs from Lincoln’s White House library. The threat of fire was a constant waking nightmare in Oldroyd’s life. While he did his best to control what went on inside his museum, he had no control over what happened outside. His life’s work of collecting precious Lincoln objects, over 3,500 at last count, could be gone in the flash of a pan.

ADDITIONAL IMAGES.

The Gun That Killed Vincent Van Gogh?

Original Publish Date February 15, 2024.

https://weeklyview.net/2024/02/15/the-gun-that-killed-vincent-van-gogh/

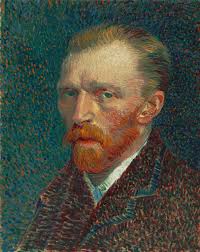

I have spent the past 12 years on a quest. A quest to discover a little-known Lincoln collector turned museum curator named Osborn H. Oldroyd. I have written about Oldroyd many times and, sometimes, the mere mention of his name elicits groans from family and friends whom I’ve forced to share my obsession, whether they want to or not. No worries, I’m not going down that road again today. I simply mention him regarding another of my early obsessions: artist Vincent van Gogh. I know, I know, Oldroyd to Van Gogh? Evel Knievel couldn’t have made that jump. Stay with me now.

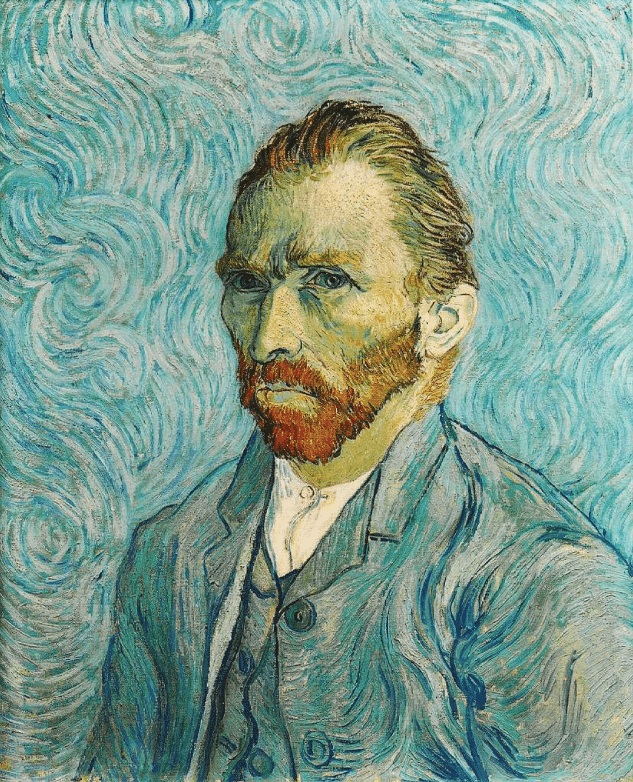

A few years back, a Paris auction house (Auction Art–Rémy Le Fur) sold the gun that Van Gogh allegedly killed himself with for approximately $182,000 to an unidentified Belgian buyer. The hammer price was almost triple the auction estimate of $44,800 to $67,000 and presumably included the buyer’s premium. Like everything in Van Gogh’s life, the sale was not without controversy. And, like many of the objects in Oldroyd’s collection (for his collection was his life), the provenance of the firearm is the sticking point. If authentic, the auction house’s description of it as “the most famous weapon in the history of art” would be unchallenged. However, let’s examine the event, the discovery, and its ultimate disposition and see what you think.

As a kid, I spent most of my free time in the library. Like many my age, my first instinct was to discover a much-wished-for connection to some (or any) historical event. I pored through the annual book of Guinness World Records looking for some record (any record) that I could conceivably break. I never found one. Then I tried to prove a genealogical link to anyone of note . . . Please be Lincoln . . . Please be Lincoln. It was not Lincoln. I was descended from a long line of boringly average people. The last hope was a connection to someone/something according to my birthday (July 30th). I found two: Jimmy Hoffa disappeared and Vincent van Gogh was buried. Oh sure, Henry Ford was born, Jamestown was founded, but not much else. So I clung to the Van Gogh square. He’s been a windmill for me to tilt at ever since.

There are so many mysteries surrounding Vincent van Gogh. Was he crazy? Was a visual problem responsible for his unique painting style? Why did his paintings, all acknowledged masterpieces, not sell until after he died? And perhaps most of all, did he REALLY kill himself? Well, he did famously cut off an ear after an argument with fellow artist Paul Gauguin and famously presented it to a prostitute in a nearby brothel. And he was confined to insane asylums more than once in his lifetime. But that gun may fuel the biggest Van Gogh mystery of them all.

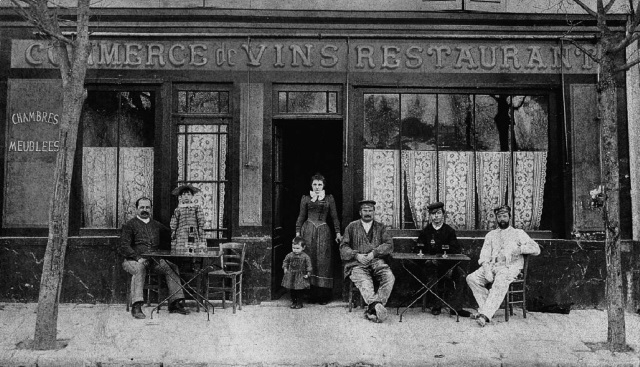

Arthur Ravoux’s Inn in Auvers-sur-Oise in France today (at left) & in Van Gogh’s time.

In May of 1890, after one of those asylum stays, Van Gogh moved into Arthur Ravoux’s Inn in Auvers-sur-Oise in France. While living in room number five there, he turned out an average of a painting a day, despite his increasingly unstable mental state. The common theory is that on Sunday, July 27th, 1890, Van Gogh ventured from his château hideaway to a nearby wheat field in the village of Auvers-sur-Oise and shot himself in the chest. The gunshot did not kill him immediately, instead, Van Gogh lost consciousness and, after waking up and in seeming defiance of his mortal injuries, left his easel against a haystack before stumbling back to his modest attic room, lit only by a small skylight, in the Ravoux Inn. He died two days later, his beloved brother Theo by his side.

According to the auction house, while admitting that it could never be 100% certain that it was the actual gun used by the artist to take his life, circumstantial evidence certainly points to that conclusion. According to museum officials, the rusted skeletal frame of the 7mm Lefaucheux revolver was “discovered where Van Gogh shot it; its caliber is the same as the bullet retrieved from the artist’s body as described by the doctor at the time; (and) scientific studies demonstrate that the gun had stayed in the ground since the 1890s.” Devil’s advocate: Lefaucheux pinfire revolvers were inexpensive and plentiful in the late 19th century. They can be found everywhere all over the world, so finding one in a field under a random tree in France may not constitute proof experts require for authentication. While stories like that may have worked in Oldroyd’s day, it certainly does not live up to modern curatorial standards. However, it does pique one’s imagination.

The story goes that a local farmer found the gun in 1965 after plowing up the very spot in the field where tradition states the artist shot himself in the stomach in July of 1890. The farmer presented the weapon to the owners of an inn in the village, and it was passed down through their family before it was given to the auction consignor’s mother, who put it up for auction. Also weighing in the gun’s favor is the fact that it is a low-power gun, which explains why the gun didn’t kill Vincent instantly. For those subscribing to the theory that Van Gogh did not shoot himself, the auction house explains that even if his death was caused by hoodlums with a grudge against him or after two young boys playing with a gun “accidentally pressed the trigger and wounded Van Gogh by mistake” the gun could still be the weapon responsible for his death. In 2016, the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam exhibited the gun as part of the show “On the Verge of Insanity, Van Gogh and His Illness.”

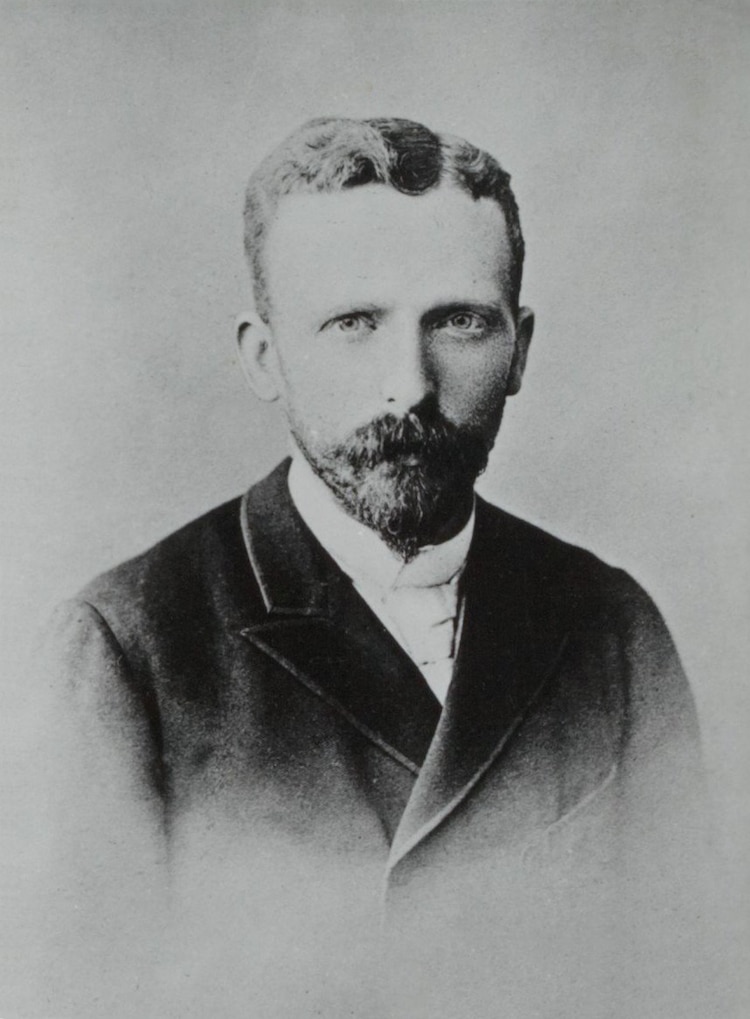

Regardless, Vincent’s myth is so complicated, his art so unattainable to all but the ultra-rich, the thought of owning the pistol that killed him may strike some as irresistible. Imagine owning the ultimate instrument of tortured artistic doom, carried into an otherwise unremarkable wheat field in northern France in late July of 1890 by a man tortured with night terrors and “overwhelmed by boredom and grief.” Did the nightmares of mental illness finally prove too much to bear? Is this the final instrument of self-martyrdom? I’ll leave that for you, the reader, to decide. Shortly before his death, on July 2, writing to his brother Theo, Vincent commented: “I myself am also trying to do as well as I can, but I will not conceal from you that I hardly dare count on always being in good health. And if my disease returns, you would forgive me. I still love art and life very much…” Eight days later, Vincent wrote Theo in French, “Je me sens – raté” (I feel failed), and added: “And the prospect grows darker, I see no happy future at all.” Before his death at 1:30 in the morning, Vincent’s last words to his brother were remembered as “La tristesse durera toujours” (The sadness will last forever).

On the afternoon of July 30th, Van Gogh’s body was laid out in his attic room, surrounded by his final canvases and masses of yellow flowers including dahlias and sunflowers. His easel, folding stool, and paintbrushes were placed before the coffin. Van Gogh’s last retreat at the Auberge Ravoux has remained intact since his death, as according to legend a room where a suicide took place must never again be rented out. Legend states that the room remained sealed up for almost a century for fear of bad luck. The room is unfurnished, except for a chair. However, like Oldroyd’s museum in the House Where Lincoln Died in Washington D.C., Van Gogh’s spirit can be felt there, permeating the very floors, joists, ceiling, and walls where he passed.

Fun conversation with Dave Taylor about Doc Temple & Osborn Oldroyd.

In Search of Ann Rutledge: Lincoln’s lost love.

Original publish date March 23, 2023. https://weeklyview.net/2023/03/23/in-search-of-ann-rutledge-lincolns-lost-love/

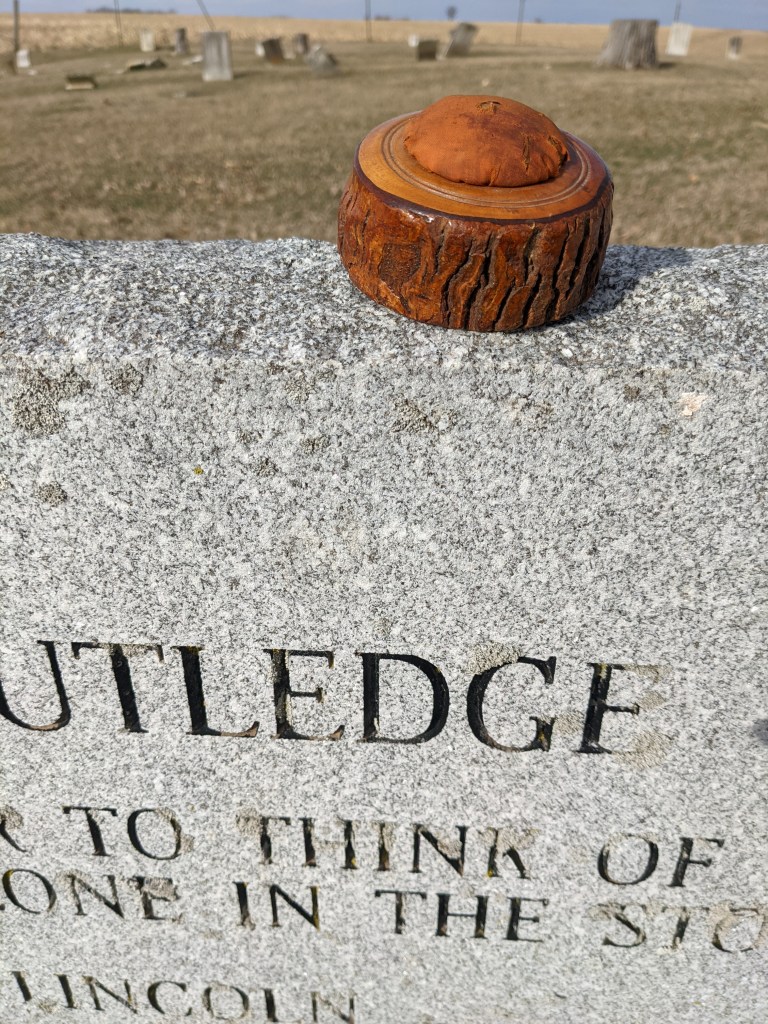

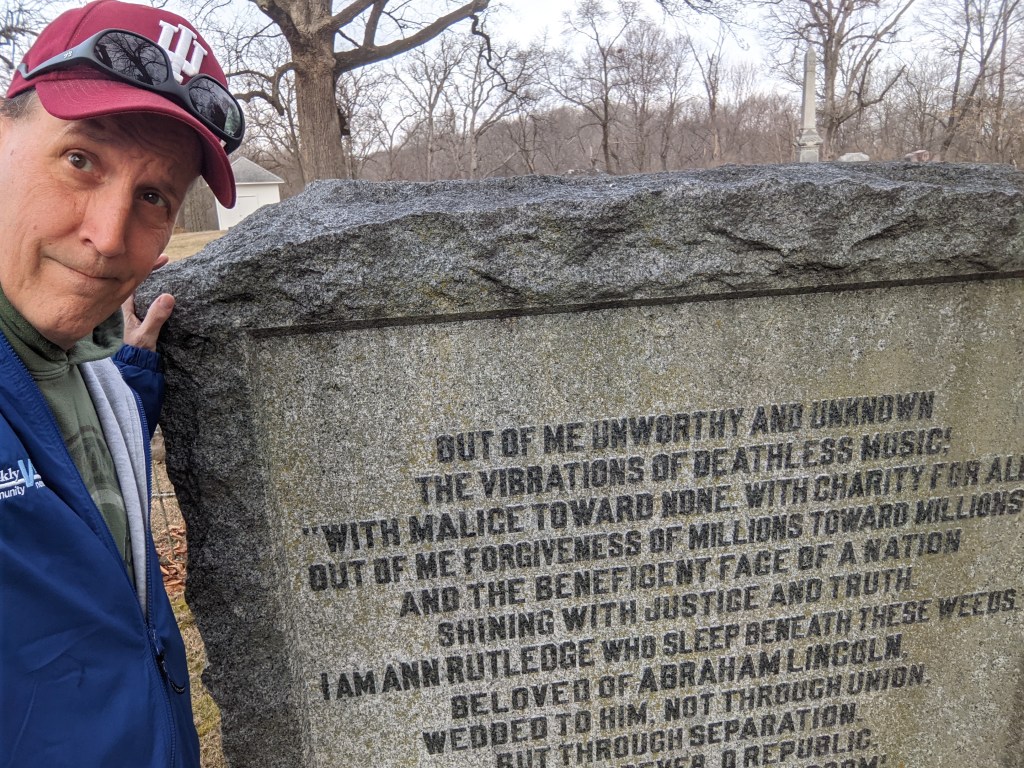

(Author’s trinket explained below)

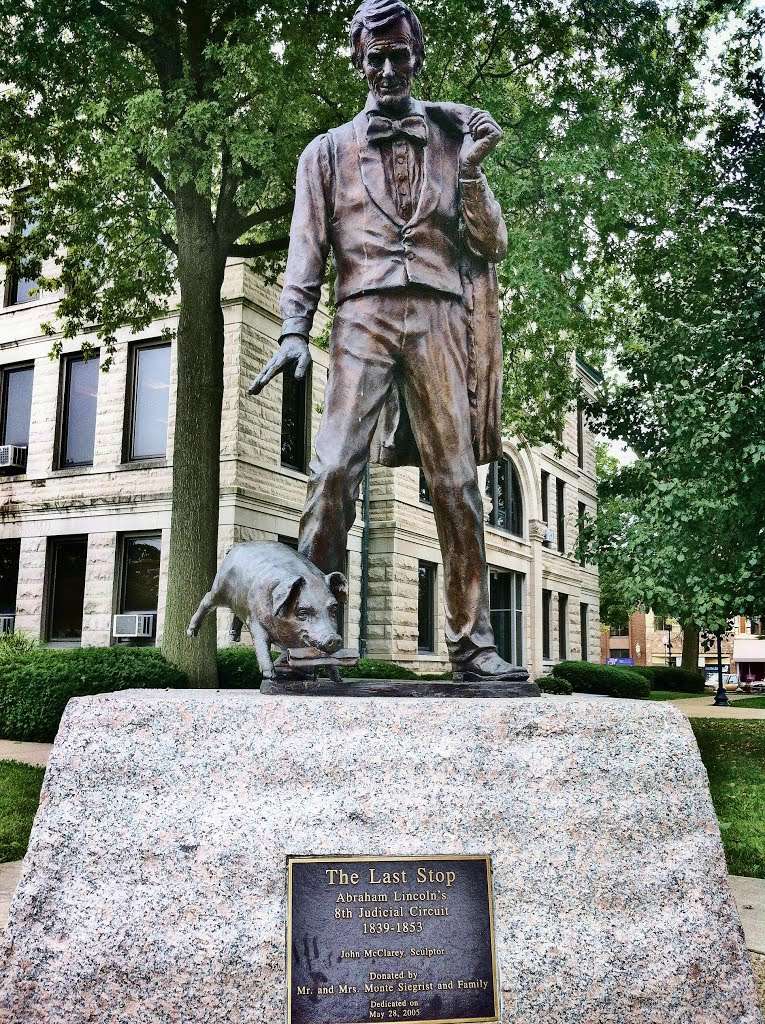

On March 1 I visited Springfield Illinois while working on an ongoing book project. My wife Rhonda wanted me out of the house for a couple of days for heavy spring cleaning. So I took advantage of an opportunity to visit some of the places I had long wished to visit but never seemed to get to. I visited a few of the markers on Lincoln’s 400-mile 8th judicial court circuit that he regularly traveled as a young lawyer during the 1840s and 1850s. I visited the courthouse in Taylorsville, where Lincoln’s court proceedings were often interrupted by the sounds of squealing pigs rooting under the courthouse floor — once so loudly that Lincoln asked the judge for a “writ of quietus” to calm the commotion. As you might imagine, Illinois is full of interesting Lincoln sites off the beaten path.

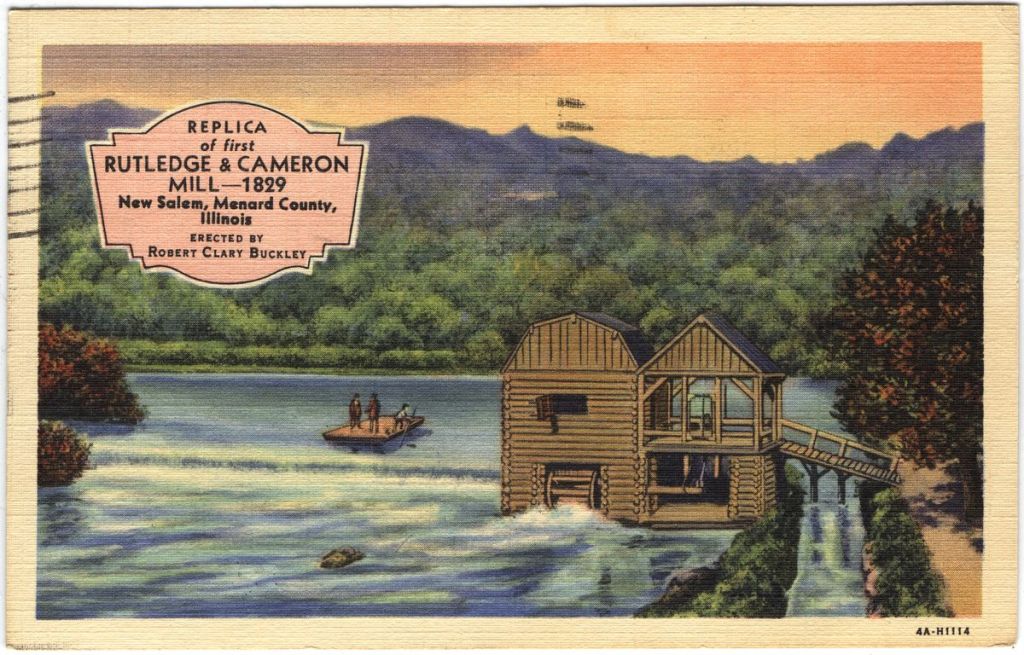

The place that I longed to see most was the final resting place of Abraham Lincoln’s first love, Ann Mayes Rutledge. She was born on January 7, 1813, near Henderson, Kentucky, the third of ten children born to Mary Ann Miller Rutledge and James Rutledge. In 1829, her father moved to Illinois and became one of the founders of New Salem, a community located 21 miles northwest of Springfield.

James Rutledge built a dam, sawmill, and gristmill in New Salem and is credited with laying out the town and selling the first lots of land there. In time, he converted his home into a tavern and inn where Ann worked — eventually, she took over the family business. Allegedly, Ann was the first (some say the only) girl to attend New Salem School. She was described as physically beautiful, 5 feet, 3 inches tall, 120 pounds with auburn hair, blue eyes, and a fair complexion. Her attitude was always positive, described as sweet and angelic, beloved by all who knew her. Her schoolteacher, Mentor Graham, described her as beautiful, amiable, kind, and an exceptionally good scholar. In 1832, young Abraham Lincoln boarded at the Rutledge Inn, where he got to know her.

While historians may disagree on the depth of her relationship with the rail splitter, there is no doubt that Ann Rutledge knew Abraham Lincoln. Ann died before the invention of photography, so no photos of her exist and no contemporary drawings of her have ever been found. Little in the way of verifiable data survives about Ann. Most of the details of her life were collected by Lincoln’s law partner of 17 years, former Springfield Mayor William Herndon. Billy was among the first to research those early years of Lincoln. While researching his book on Lincoln, Herndon retraced Lincoln’s tracks through central Illinois and southern Indiana. Billy Herndon did not care for Mary Lincoln and the feeling was mutual. So it comes as no surprise that Herndon was the first to push the relationship between Abraham and Ann.

Herndon’s details about Ann’s life came from people that knew Ann in New Salem, witnesses that historians have called “Herndon’s informants.” Rutledge neighbor James Short described Ann as “a good-looking, smart, lively girl, a good housekeeper, with a moderate education.” Likewise, Harvey Lee Ross, a boarder at the Rutledge family tavern in New Salem described Ann as “very handsome and attractive, as well as industrious and sweet-spirited. I seldom saw her when she was not engaged in some occupation – knitting, sewing, waiting on tables, etc…I think she did the sewing for the entire family. Lincoln was boarding at the tavern and fell deeply in love with Ann, and she was no less in love with him. They were engaged to be married, but they had been putting off the wedding for a while, as he wanted to accumulate a little more property and she wanted to go longer to school.” When interviewed by Herndon, Ann’s family testified that Lincoln was certainly smitten with Ann.

Not only was Lincoln attracted to Ann’s good looks, but he was also intrigued by her intelligence, a rare quality on the frontier. Herndon once said “I believe his very soul was wrapped up in that lovely girl. It was his first love – the holiest thing in life – the love that cannot die.” That all changed on August 25, 1835, when typhoid fever swept through New Salem and 22-year-old Ann Rutledge died. Legend states that Ann called Lincoln to her deathbed for a final goodbye before passing. Ann’s death unhinged Lincoln, leaving him severely depressed, a condition he would battle for the rest of his life. Upon her death, Lincoln confided to Mentor Graham that he felt like committing suicide, but Graham reassured him that “God has another purpose for you.” New Salem resident John Hill later said “Lincoln bore up under it very well until some days afterward when a heavy rain fell, which unnerved him.” Lincoln’s friend, Henry McHenry, testified that after Ann’s passing Lincoln “seemed quite changed, he seemed retired, & loved solitude, he seemed wrapped in profound thought, indifferent, to transpiring events.”

According to author Harvey Lee Ross in his book The Early Pioneers and Pioneer Events of the State of Illinois, Lincoln told friends: ‘My heart is buried in the grave with that dear girl. He would often go and sit by her grave and read a little pocket Testament he carried with him.” Another New Salem neighbor, Isaac Cogdal told Herndon that President-elect Lincoln confessed his love of Ann to him before leaving Springfield for Washington. “I did really – I ran off the track: it was my first. I loved the woman dearly & sacredly: she was a handsome girl – would have made a good loving wife – was natural and quite intellectual, though not highly educated…I did honestly – & truly love the girl & think often – often of her now.”

Ann was originally buried at the Old Concord graveyard (sometimes called Goodpasture graveyard) a pioneer cemetery located about seven miles northwest of New Salem. Some 200 people were buried there, many of whom knew Abraham and Ann personally. Today they stand as silent sentinels to the truthfulness of their courtship. Lincoln visited her gravesite frequently. According to Herndon, after Ann’s death, Lincoln “sorrowed and grieved, rambled over the hills and through the forests, day and night. He suffered and bore it for a while like a great man — a philosopher. He slept not, he ate not, joyed not. This he did until his body became emaciated and weak, and gave way. In his imagination he muttered words to her he loved … Love, future happiness, death, sorrow, grief, and pure and perfect despair, the want of sleep, the want of food, a cracked and aching heart, and intense thought, soon worked a partial wreck of body and of mind.”

To friends, Lincoln claimed that the thought of “the snows and rains fall(ing) upon her grave filled him with indescribable grief.” For days following her death, damp, stormy days, and gloomy weather triggered a deep depression that sent Lincoln to her gravesite where he lay prostrate over Ann’s grave. Lincoln’s behavior became so alarming that his friends sent him to the house of another kind friend, Bowlin Greene, who lived in a secluded spot hidden by the hills, a mile south of town. According to Herndon, “Here Lincoln remained for weeks under the care and ever-watchful eye of this noble friend, who gradually brought him back to reason or at least a realization of his true condition.” Yes, Abraham Lincoln knew Old Concord Graveyard well.

Here’s where the story takes a strange turn. Many years later, some enterprising citizens of nearby Petersburg, a town located four miles to the north, decided that Ann’s grave could help put their town on the map. Chief among them was Petersburg undertaker Samual Montgomery, ironically an elderly relative of Ann’s, and a cemetery promoter with the improbable name of D.M. Bone. These ad-hoc graverobbers decided it would be financially advantageous to move Rutledge’s remains for fear that their cemetery needed the draw of a famous name to compete with crosstown rival Rose Cemetery.

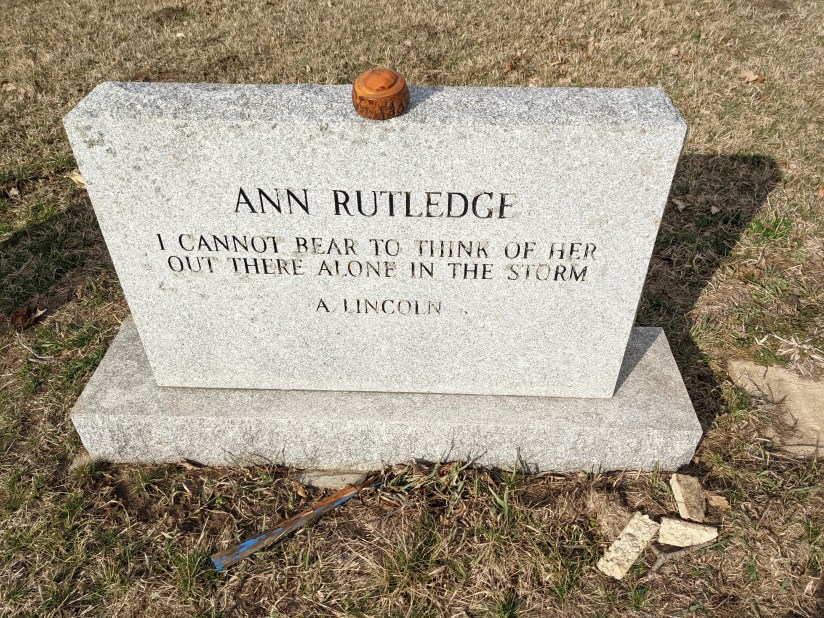

For three decades, all that marked Ann’s grave at the new cemetery was a rough stone with her name emblazoned in white letters on the front. In January 1921, Rutledge’s grave was fitted out with a magnificent granite monument inscribed with the text of the poem “Anne Rutledge,” from Edgar Lee Masters’s Spoon River Anthology. His words, engraved on her cenotaph at Oakland Cemetery are haunting: “I am Ann Rutledge who sleeps beneath these weeds, Beloved in life of Abraham Lincoln, Wedded to him, not through union, But through separation. Bloom forever, O Republic, From the dust of my bosom!” Regardless of the attempts by Lincoln biographers like Herndon, Ward Hill Lamon (Lincoln’s bodyguard), Carl Sandburg, and Indiana Senator Albert Beveridge to legitimize the Lincoln/Rutledge romance as fact, by the 1930-40s, Lincoln scholars expressed increased skepticism of the story. Most biographers agree that Lincoln and Rutledge were close, but several historians point to a lack of evidence of a love affair between them.

For my part, as a lifelong student of Lincoln, I choose it to be true. It is for that reason that I traveled to Petersburg, Illinois in search of Ann Rutledge’s grave. Finding Oakland Cemetery is an easy task and worth the visit. The massive granite marker is the most impressive memorial in the graveyard. Surrounded by an equally impressive wrought iron fence, the rough stone marker that originally graced her final resting place remains tucked away at the front of the plot although her name is slowly eroding away. Edgar Lee Masters’ epitaph is clear, legible, and easy to read. Master’s grave is only yards away. As impressive as the site may be, if you know the backstory, an overpowering soullessness pervades the spot simply because she is not there.

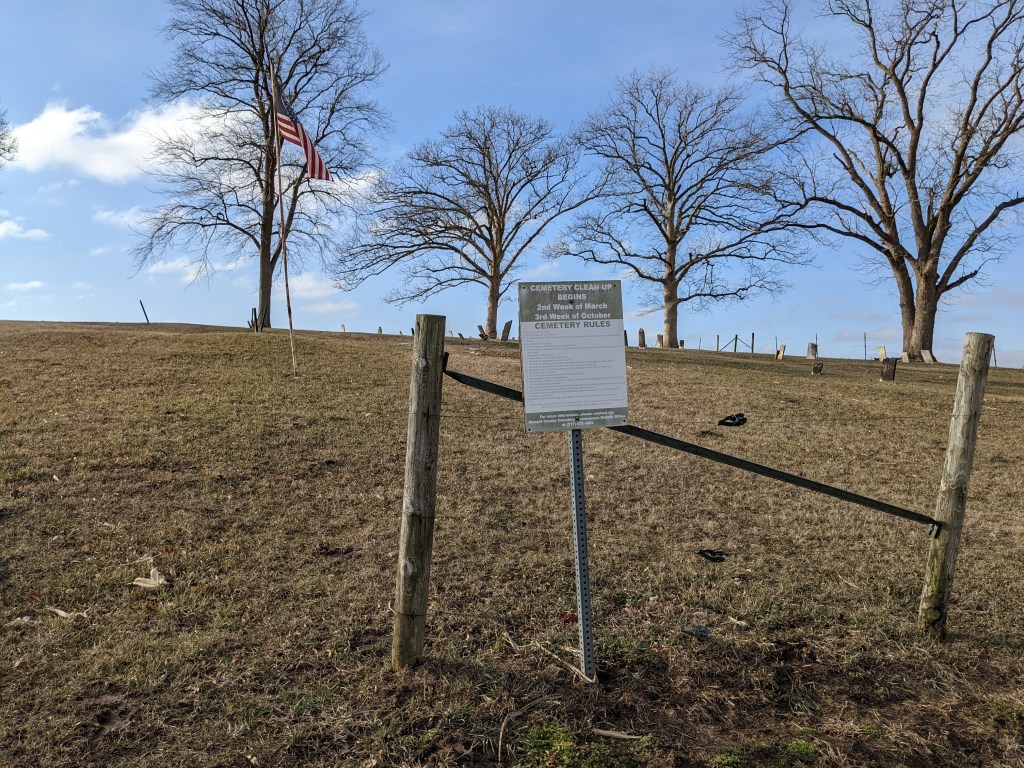

The place I really wanted to find was the Old Concord Graveyard. So I did what every stranger in a strange place does: I consulted Google maps. Oh, the navigator took me there, but just barely. The map directions led me to Route 97 North and the Lincoln Trail Road through the farm fields of Menard County, off the paved highway, and onto a gravel road. Like most midwestern roads, the winding serpentine roadways mimic the buffalo traces of centuries past. They wind through hills cut not by machinery, but by carts pulled by oxen and horses generations ago. Blind hills make the driver wonder if the road continues past each rise and dangerous curves make you tighten your grip on the steering wheel. Along the way, pheasants and quail stroll leisurely along the roadside. This is their domain and they fear no man out here.

Time and time again, my GPS ended in front of a brick farmhouse proclaiming “You have reached your destination.” This was not a cemetery, so I retraced my route, and five miles later, I found myself in the same spot. Finally, I pulled into the driveway and knocked on the door. My summons was answered by a friendly dog followed by a lovely mature woman. I threw myself upon the mercy of a stranger, apologized for the intrusion, and asked if this was the place. She smiled and said, “Well, you’re close” and led me to the side of the house where she pointed to the cemetery about a half mile in the distance.

She told me to head back out on the county road and keep turning left until I found an abandoned, dried-up waterway through a pair of cornfields. She said, “It is not really a road but the county crews still drive their equipment back there to keep the grass cut, so you should be able to find it,” The cemetery can not be seen from the gravel road, so it took me two passes to find it. When I did, I nervously went offroading about a quarter mile back upon a grassy lane between two cornfields. It had been raining before my arrival and rain was predicted for later that day, so I was less than confident that I could make it without getting stuck. Luckily, I arrived there safely.

The ancient graveyard is filled with veterans of the Revolutionary War like Robert Armstrong from North Carolina who died September 9th, 1834. Next to Robert is the marker of his son, Jack Armstrong of the Clary Grove gang, who famously fought Abe Lincoln to a draw in a wrestling match in New Salem. The battle became the stuff of legend and ultimately got Lincoln inducted into the Wrestling Hall of Fame. It did nothing for Jack Armstrong though. He died in 1854 although his stone incorrectly lists the death date as 1857. Most of the stones have been laid down face up so that they may still be read. Many are broken and rest in pieces strewn about in this ancient burying ground. A flagpole stands guard with a tattered American flag that shows the scars of a constant battle with the rough winds of the Illinois plains.

Ann’s grave rests on top of the hill next to that of her father, whose body was not removed to the new cemetery. Also near Ann is the grave of her brother David who died in 1842, a decade after serving with Abraham Lincoln in the Black Hawk War. There are many Rutledges still resting here. It is likely that most, if not all of them, were known by Ann or she by them. From Ann’s grave, I could look over my shoulder and see the farmhouse where I started. I wonder to myself what it would be like to live so close to such a magical place. Talking with the lady she told me they had been living there for 30 years. They had directed a few travelers like me to the spot, but not many. She informed me that her home was built by the Grosbaugh family and that it would have been there in 1835 when Ann drew Lincoln there. She pointed to an ancient natural stone step in the sideyard between her house and the graveyard and stated, “This was the watering trough and buggy turnaround, the start of a path that used to lead directly to the cemetery. It hasn’t been used in over a century.”

I’ve chased Lincoln all over this country. I’m sure I have stepped in his footprints many times. This spot, the Old Concord Cemetery, is the toughest Lincoln site I have ever found. It is impossible to find on your own and no map will lead you here. Here young Abraham Lincoln came day after day to mourn over his lost love. Here he lay upon her grave from autumn to winter, protecting her because he could not bear the thought of it raining or snowing upon her mortal remains. Today, a modern stone rests in Old Concord Graveyard on the spot that reads: “Original Grave of Ann Mayes Rutledge Jan. 7, 1813-August 25, 1835. Where Lincoln Wept.” Lincoln was here and here Ann remains. Her body literally melted into the soil of the central Illinois prairie. Here is the lone individual spot where anyone may visit to experience the raw emotion that was Abraham Lincoln.