Original publish date April 11, 2024. https://weeklyview.net/2024/04/11/george-alfred-townsend-and-the-war-correspondent-memorial-arch/

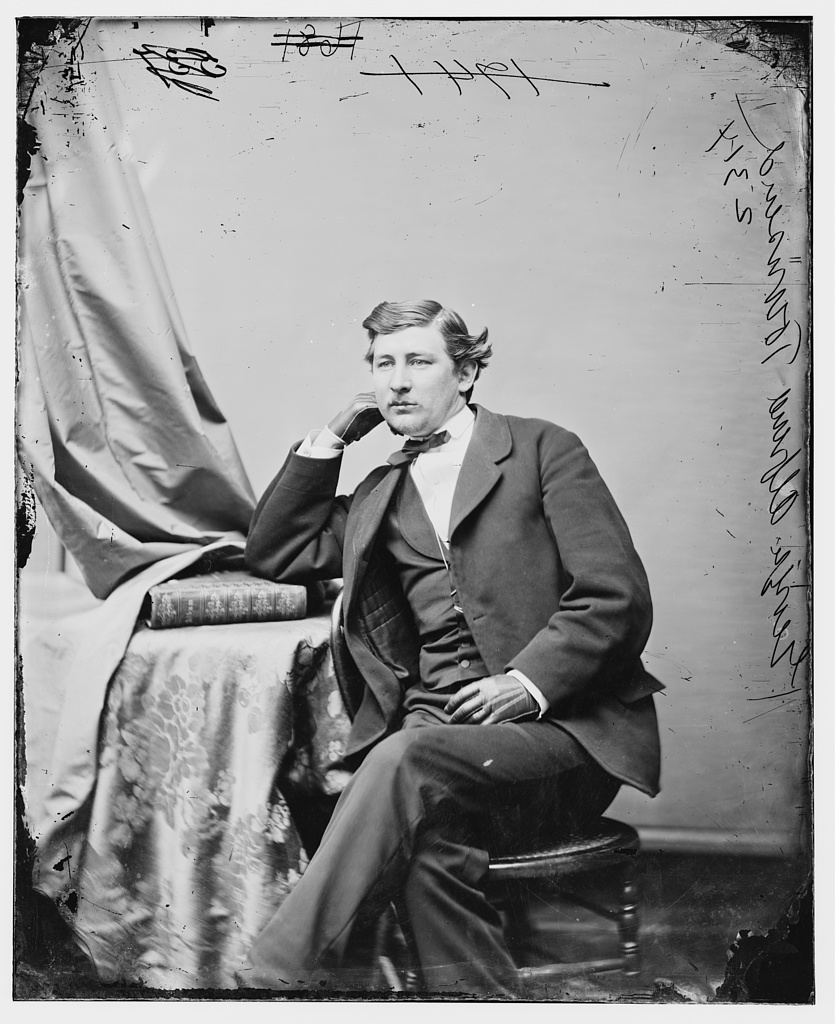

Next week will witness another sad passing in American history: the 159th anniversary of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Because I live with this date dancing around in my head more than most, I want to share my experience (and admiration) for a peripheral character in that tragedy: George Alfred Townsend. Born in Georgetown, Delaware on January 30, 1841, Townsend was one of the youngest war correspondents during the American Civil War. Soon after graduation from high school (with a Bachelor of Arts) in 1860, Townsend began his career as a news editor with The Philadelphia Inquirer. In 1861, he moved to the Philadelphia Press as city editor. As the war broke out, he worked for the New York Herald as a war correspondent in Philadelphia.

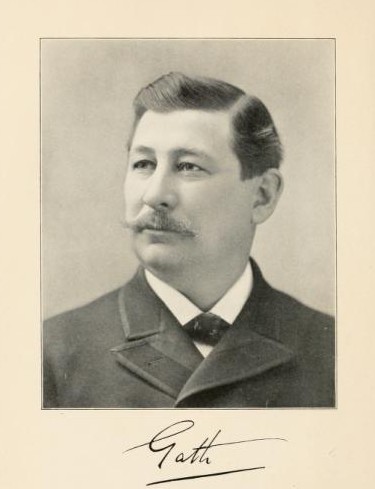

By April 1862, George got his big break when General George McClellan rode through Philadelphia on his way to Washington. That fortuitous meeting would propel young Townsend to exclusive access to many of the Civil War’s greatest battles. One of America’s first nationally syndicated columnists, Townsend used the pen name “Gath” for his newspaper columns. Gath was an acronym of his initials with the addition of an “H” at the end. Friends and contemporaries like Mark Twain, Bret Harte, and Noah Brooks, claimed the “H” stood for “Heaven” while wags and rivals claimed it stood for “Hell.” Gath himself was inspired by the biblical passage uttered by David after the death of King Saul in II Samuel 1:20, “Tell it not in Gath, publish it not in the streets of Askalon.”

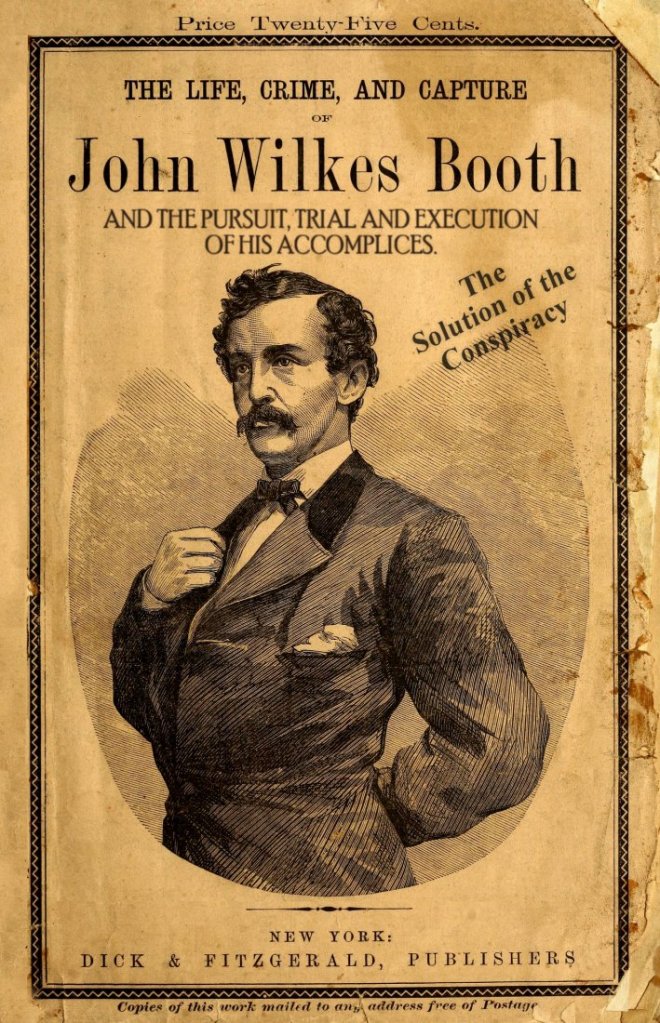

While Townsend won accolades for his work covering the war, it was his coverage of the Lincoln assassination that he is best remembered for. His detailed columns (which he called “letters”) about the tragedy were filed between April 17 – May 17 and would later be published as The Life, Crime and Capture of John Wilkes Booth. Published in 1865, Townsend’s book offers a full sketch of the assassin, the conspiracy, the pursuit, trial, and execution of his accomplices. As a lifelong student of Lincoln, I have read countless books, articles, letters, and various accounts centered on his life. It was in George Alfred Townsend’s “letters” that I found my holy Grail. Townsend’s description of Lincoln in his coffin made me feel as if I were standing there myself. His description of Lincoln’s office left me awestruck and wishful. In my opinion, it would be hard to find a more worthy example of Victorian journalism than these excerpts from Gath’s “letters”.

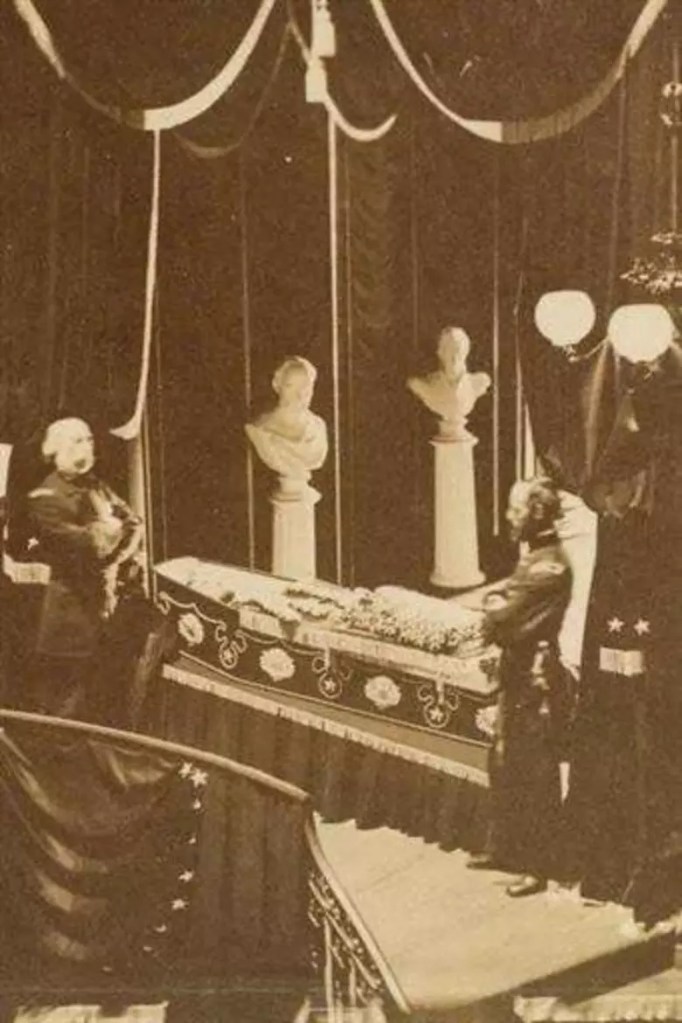

“Deeply ensconced in the white satin stuffing of his coffin, the President lies like one asleep. Death has fastened into his frozen face all the character and idiosyncrasy of life. He has not changed one line of his grave, grotesque countenance, nor smoothed out a single feature. The hue is rather bloodless and leaden; but he was always a sallow. The dark eyebrows seem abruptly arched; the beard, which will grow no more, is shaved close, save the tuft at the short small chin. The mouth is shut, like that of one who had put the foot down firm, and so are the eyes, which look as calm as slumber. The collar is short and awkward, turned over the stiff elastic cravat, and whatever energy or humor or tender gravity marked the living face is hardened into its pulseless outline. No corpse in the world is better prepared according to appearances. The white satin around it reflects sufficient light upon the face to show us that death is really there; but there are sweet roses and early magnolias, and the balmiest of lilies strewn around, as if the flowers had begun to bloom even upon his coffin. Looking on interruptedly! for there is no pressure, and henceforward the place will be thronged with gazers who will take from the site its suggestiveness and respect. Three years ago, when little Willie Lincoln died, Doctors Brown and Alexander, the embalmers or injectors, prepared his body so handsomely that the President had it twice disinterred to look upon it. The same men, in the same way, have made perpetual these beloved lineaments. There is now no blood in the body; it was drained by the jugular vein and sacredly preserved, and through a cutting on the inside of the thigh the empty blood vessels were charged with the chemical preparation which soon hardened to the consistence of stone. The long and bony body is now hard and stiff, so that beyond its present position it cannot be moved any more than the arms or legs of a statue. It has undergone many changes. The scalp has been removed, the brain taken out, the chest opened and the blood emptied. All that we see of Abraham Lincoln, so cunningly contemplated in his splendid coffin, is a mere shell, an effigy, a sculpture. He lies in sleep, but it is the sleep of marble. All that made the flesh vital, sentiment, and affectionate is gone forever.”

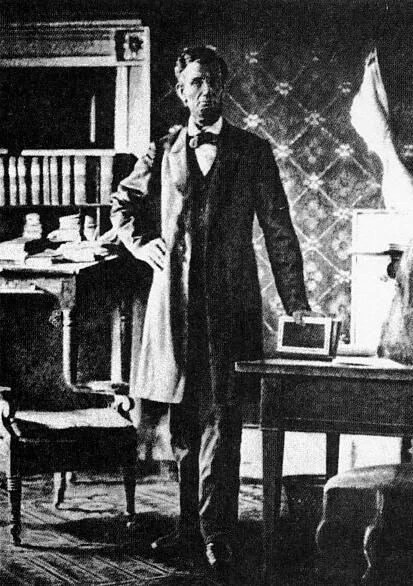

On May 14, 1865, the day Abraham Lincoln’s body was placed on the funeral train to leave Washington DC forever, Townsend visited the White House. Mary Lincoln still resided there with her beloved son Tad, too distraught to leave the White House. “I am sitting in the President’s office. He was here very lately, but he will not return to dispossess me of the high-backed chair he filled so long, nor resume his daily work at the table where I am writing. There are here only Major Hay (Salem Indiana’s John Hay, Lincoln’s private secretary) and the friend who accompanies me. A bright-faced boy runs in and out, darkly attired, so that his fob chain of gold is the only relief to his mourning garb. This is little Tad, the pet of the White House. That great death, with which the world rings, has made upon him only the light impression which all things make upon childhood. He will live to be a man pointed out everywhere, for his father’s sake; and as folks look at him, the tableau of the murder will seem to encircle him.”

Townsend further describes Lincoln’s office, just as he left it. “The room is long and high, and so thickly hung with maps that the color of the wall cannot be discerned. The President’s table at which I am seated adjoins a window at the farthest corner; and to the left of my chair as I reclined in it, there is a large table before an empty grate, around which there are many chairs, where the cabinet used to assemble. The carpet is trodden thin, and the brilliance of its dyes is lost. The furniture is of the formal cabinet class, stately and semi-comfortable; there are bookcases sprinkled with the sparse library of a country lawyer, but lately plethoric, like the thin body which has departed in its coffin. Outside of this room, there is an office, where his secretaries sat – a room more narrow but as long – and opposite this adjacent office, a second door, directly behind Mr. Lincoln’s chair leads by a private passage to his family quarters. I am glad to sit here in his chair, where he has spent so often, – in the atmosphere of the household he purified, and the site of the green grass and the blue river he hallowed by gazing upon, in the very center of the nation he preserved for the people, and close the list of bloodied deeds, of desperate fights of swift expiations, of renowned obsequies of which I have written, by indicting at his table the goodness of his life and the eternity of his memory.”

“They are taking away Mr. Lincoln’s private effects, to deposit them wheresoever his family may abide, and the emptiness of the place, on this sunny Sunday, revives that feeling of desolation from which the land has scarce recovered. I rise from my seat and examine the maps; they are from the coast survey and engineer departments, and exhibit all the contested grounds of the war: there are pencil lines upon them where someone has traced the route of armies, and planned the strategic circumferences of campaigns. Was it the dead President who so followed the March of Empire, and dotted the sites of shock and overthrow? So, in the half-gloomy, half-grand apartment, roamed the tall and wrinkled figure whom the country had summoned from his plain home into mighty history, with the geography of the Republic drawn into a narrow compass so that he might lay his great brown hand upon it everywhere. And walking to and fro, to and fro, to measure the destinies of arms, he often stopped, with his thoughtful eyes upon the carpet, to ask if his life were real and he were the arbiter of so tremendous issues, or whether it was not all a fever-dream, snatched from his sofa in the routine office of the Prairie state.”

“I see some books on the table; perhaps they have lain there undisturbed since the reader’s dimming eyes grew nerveless. A parliamentary manual, a thesaurus, and two books of humor, “Orpheus C. Kerr,” and “Artemis Ward.” These last were read by Mr. Lincoln in the pauses of his hard day’s labor. Their tenure here bears out the popular verdict of his partiality for a good joke; and, through the window, from the seat of Mr. Lincoln, I see across the grassy grounds of the capitol, the broken shaft of the Washington Monument, the long bridge and the fort-tipped Heights of Arlington, reaching down to the shining riverside. These scenes he looked at often to catch some freshness of leaf and water, and often raised the sash to let the world rush in where only the nation abided, and hence on that awful night, he departed early, to forget this room and its close applications in the abandon of the theater. I wonder if it were the least of Booth’s crimes to slay this public servant and the stolen hour of recreation he enjoyed but seldom. We worked his life out here, and killed him when he asked a holiday.”

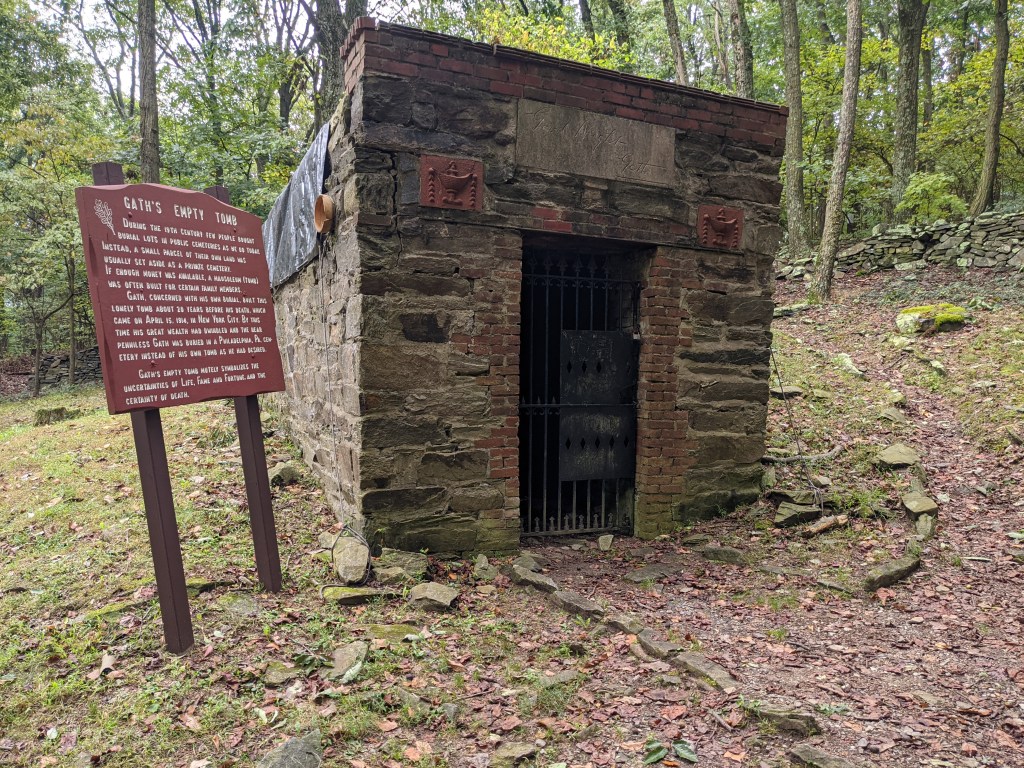

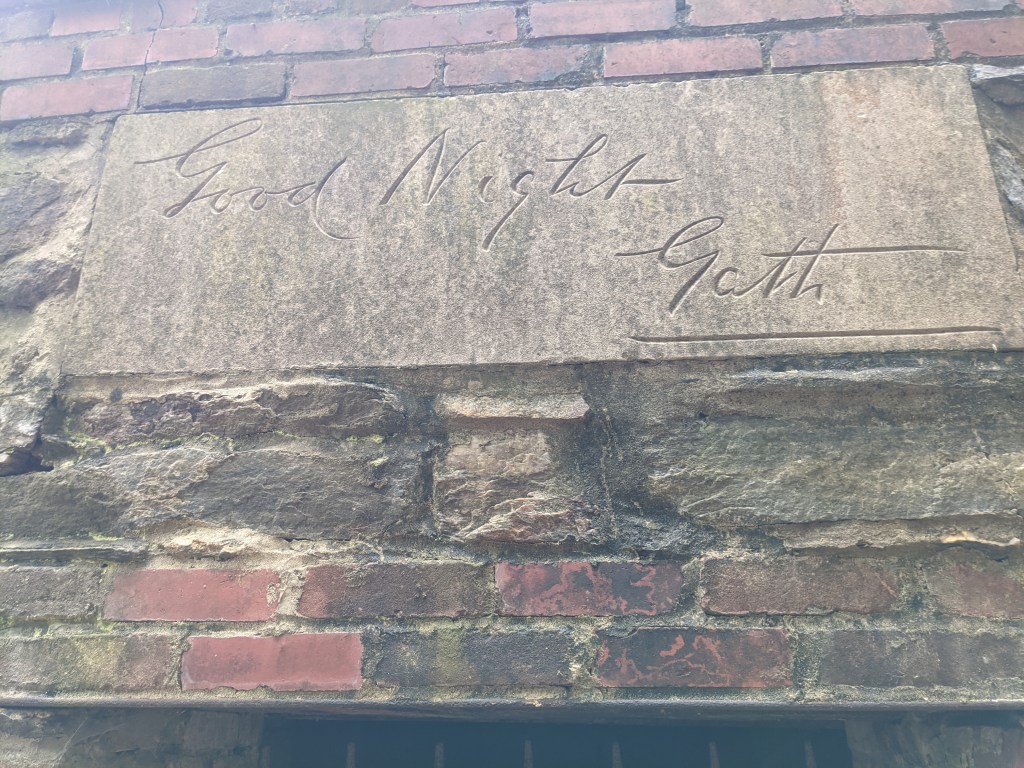

As one of the most successful journalists of his day, Townsend accumulated a tidy fortune. He used much of that fortune to build a 100-acre baronial estate near Crampton’s Gap, South Mountain, Maryland known as “Gapland”. The Civil War Battle of Crampton’s Gap was fought as part of the Battle of South Mountain on September 14, 1862, and resulted in 1,400 combined casualties. Tactically the battle resulted in a Union victory because they broke the Confederate line and drove through the gap. Strategically, the Confederates were successful in stalling the Union advance and were able to protect the rear. Gath literally bought the battlefield upon which he built his estate. The estate was composed of several buildings, including Gapland Hall, Gapland Lodge, the Den and Library Building, and a brick mausoleum (notable for its inscription of “Good Night Gath” above the entrance).

In 1896, Townsend built a monument to war correspondents to memorialize the contributions of his colleagues North and South. Dedicated in 1896, The War Correspondent Memorial Arch is 50 feet high and 40 feet wide and is the only monument in the world dedicated solely to war correspondents. Not only does the arch stand on Townsend’s original estate (operated by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources), it also rests smack dab in the middle of the Appalachian National Scenic Trail. Furthermore, the woods surrounding Gapland and the nearby town of Burkittsville were the setting for the 1999 horror film Blair Witch Project.

Last September, I traveled to the Catoctin Mountains to visit Townsend’s estate not far from the Antietam battlefield. Townsend’s Gapland estate is now known as Gathland State Park. Several buildings still stand, including Gapland Hall (which is the park headquarters) and the mausoleum, while other buildings are mere shadows of their former self. Townsend left Gapland in 1911 and died in New York City three years later on April 15, 1914. The 49th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s death. He was buried at Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia.

His brick mausoleum, fronted by an ominous-looking iron gate causing it to look more like a jail cell than a tomb, stands empty, its roof slowly caving in. Although the object of my quest was The War Correspondent Memorial Arch, I could not help but spend most of my time seated beneath that empty tomb smoking a cigar. While the hale and hearty hikers pausing briefly at the foot of the Appalachian Trail might not have appreciated my vice, as I stared at the epitaph above the iron gate above Townsend’s unused tomb, George Alfred Townsend would understand. Good Night Gath.

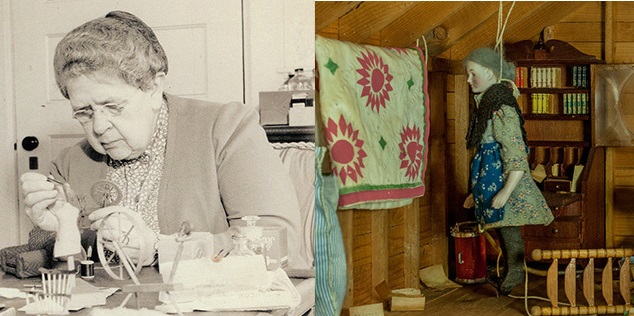

Housed in impressive looking wood and glass locked cases, they are not unlike the ancient penny arcade mechanical machines recalled by every baby boomer’s childhood. Except these scenes are populated by dead bodies, gruesome instruments of death and startling realistic blood spatter patterns. The scenes take place in attics, barns, bedrooms, log cabins, bathrooms, garages, kitchens, parsonages, saloons, jails, porches and even a woodman’s shack. Sometimes, it’s easy to determine the cause of death, but look closer and conclusions are tested. There is more than meets the eye in the Nutshell Studies and any object could be a clue. Every element of the dioramas-angles of minuscule bullet holes, placements of window latches, discoloration of painstakingly painted miniature corpses-challenges the powers of observation and deduction.

Housed in impressive looking wood and glass locked cases, they are not unlike the ancient penny arcade mechanical machines recalled by every baby boomer’s childhood. Except these scenes are populated by dead bodies, gruesome instruments of death and startling realistic blood spatter patterns. The scenes take place in attics, barns, bedrooms, log cabins, bathrooms, garages, kitchens, parsonages, saloons, jails, porches and even a woodman’s shack. Sometimes, it’s easy to determine the cause of death, but look closer and conclusions are tested. There is more than meets the eye in the Nutshell Studies and any object could be a clue. Every element of the dioramas-angles of minuscule bullet holes, placements of window latches, discoloration of painstakingly painted miniature corpses-challenges the powers of observation and deduction. Bruce says, “Look at the miniature sewing machine (about the size of your thumbnail) it’s threaded. There is graffiti on the jail cell walls. The newspapers (less than the size of a postage stamp) are real. Each one had to be printed on a tiny press, the newsprint is immeasurably small. The Life magazine cover is accurate to the week of the crime. The ant-sized cigarettes are hand rolled and burnt on the end. Amazing!” Bruce, who came to the M.E.’s office in 2012, says that although he’s been over every inch of each diorama, he is still making new discoveries.

Bruce says, “Look at the miniature sewing machine (about the size of your thumbnail) it’s threaded. There is graffiti on the jail cell walls. The newspapers (less than the size of a postage stamp) are real. Each one had to be printed on a tiny press, the newsprint is immeasurably small. The Life magazine cover is accurate to the week of the crime. The ant-sized cigarettes are hand rolled and burnt on the end. Amazing!” Bruce, who came to the M.E.’s office in 2012, says that although he’s been over every inch of each diorama, he is still making new discoveries.

The Nutshell Studies made their debut at the homicide seminar in Boston in 1945. It was the first of it’s kind. Bruce says, “Frances’ intention was for Harvard University to do for crime scene investigation what they had done for their famous business school. When Frances died in 1962, support evaporated and by 1966, the department of legal medicine at Harvard was dissolved.” When asked how the displays made the trip from Harvard yard to Baltimore, Bruce states, “That’s a good question. When Harvard planned to throw them away, longtime medical examiner Russell S. Fisher brought them here in 1968. Fisher was a legend and a former student of Frances Glessner Lee. Fisher was one of the doctors called in to examine John F. Kennedy’s head wounds.”

The Nutshell Studies made their debut at the homicide seminar in Boston in 1945. It was the first of it’s kind. Bruce says, “Frances’ intention was for Harvard University to do for crime scene investigation what they had done for their famous business school. When Frances died in 1962, support evaporated and by 1966, the department of legal medicine at Harvard was dissolved.” When asked how the displays made the trip from Harvard yard to Baltimore, Bruce states, “That’s a good question. When Harvard planned to throw them away, longtime medical examiner Russell S. Fisher brought them here in 1968. Fisher was a legend and a former student of Frances Glessner Lee. Fisher was one of the doctors called in to examine John F. Kennedy’s head wounds.”