Part I

https://weeklyview.net/2025/03/13/nazis-at-arsenal-tech-what-part-1/

Original publish date March 13, 2025.

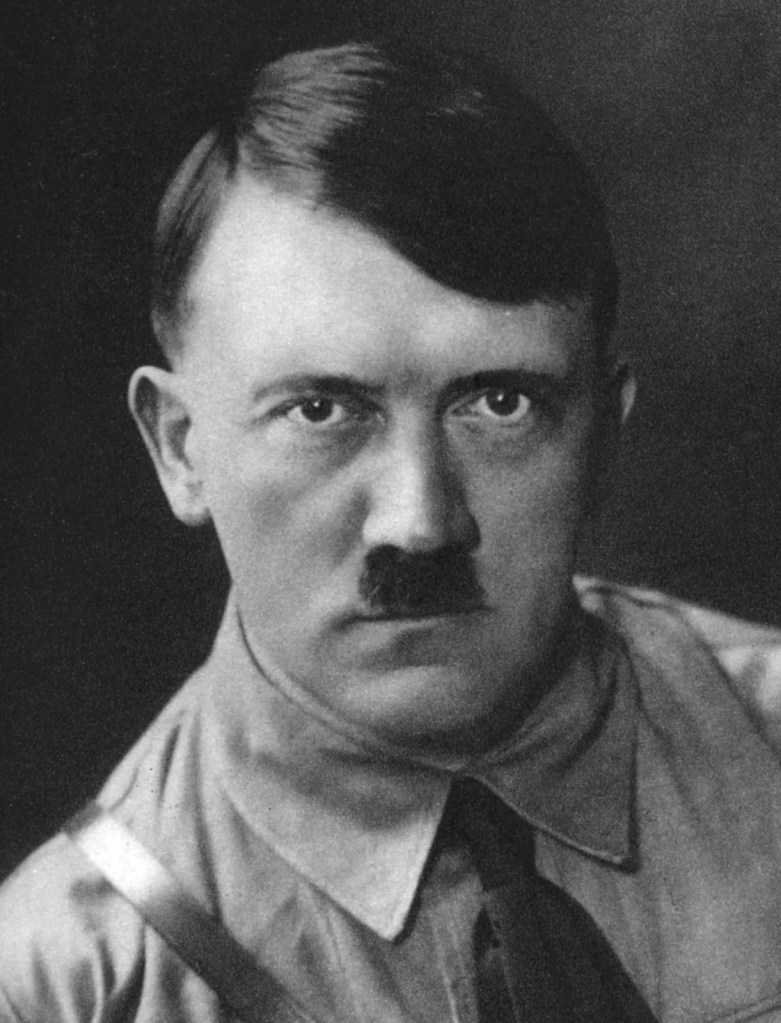

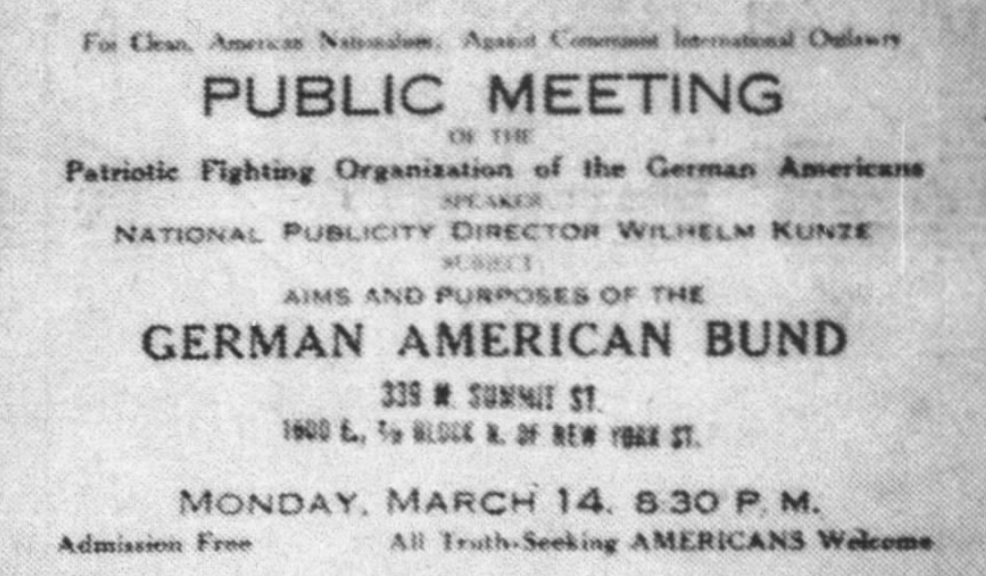

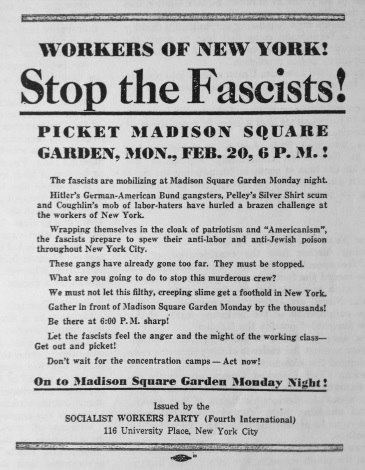

It’s true. In the years leading up to World War II, there was at least one eastside Indianapolis family openly identifying with the American Nazi Party. And three of those proud young Nazis graduated from Arsenal Technical High School. It all came to a head 87 years ago this Saturday when the Soltau home on North Summitt Street (where the La Parada Mexican restaurant now stands) came under attack by an angry mob of Circle City citizens seeking to enact their own “Night of Broken Glass” on March 15, 1938, seven months before Adolph Hitler’s Kristallnacht in Berlin, Germany in November of that same year. In March of 1938, Indianapolis newspapers were dominated by reports of German Wehrmarcht invaders poised at the gate, prepared to annex Austria into a “greater German Reich” and threatening the entire Western European theatre. Those same front pages reported on an organization of Hoosier ethnic Germans who were resolutely pro-Nazi, vehemently anti-Communist, deeply anti-Semitic, and staunchly American isolationists. In 1938, an estimated 25,000 Americans were members of this German American Bund. Indianapolis boosters hoped to swell that number by appealing to the large German immigrant community by advocating “clean American nationalism against Communist international outlawry.”

However, the German-American Bund secured very few Hoosier followers and gained little sympathy for their cause. Indiana had a well-deserved reputation for xenophobia and white nationalism that is most clearly reflected in the Ku Klux Klan’s ascent to power just over a decade before. The number of Hoosiers in league with the German-American Bund was certainly much smaller than the number of members of the 1920s KKK. Still it was committed to many of the same ideological issues as the Klan. Its history confirms the complex range of xenophobic sentiments simmering in the 20th-century Circle City.

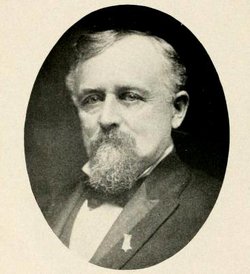

The Soltau family was closely associated with Indianapolis, particularly the east side and Irvington. John Albert Soltau (1847-1938) was a German immigrant who founded the first grocery chain in Indianapolis, the Minnesota Grocery Company. Soltau arrived here in 1873 at the age of 10. After marrying Miss Elizabeth Koehler (1851-1920), Soltau opened the first of what would become a chain of twelve grocery stores at 208 North Davidson Street. The couple had five children: William, Edward, James, John, and Benjamin. The elder Soltau remained in the grocery business for over fifty years. Three of his sons joined him, managing stores of their own. Mr. Soltau was a member of the First Evangelical Church near Lockerbie Square (where New York crosses East Street). The family residence was located at 837 Middle Drive in Woodruff Place.

In 1894, John was a Republican Ward delegate in Indianapolis. In 1902, he was an unsuccessful candidate for Marion County Recorder on the Prohibition ticket, and in 1916, he was a delegate to the national Prohibition Party convention. His long adherence to the temperance cause smacks of social conservativism, but offers no clear evidence for why his family embraced the Nazi ideology. Hoosier Prohibitionists allied themselves with the Klan’s cause in the 1920s, and in 1923, John’s brother James Garfield Soltau (1881-1932) was identified as one of the first 12,208 Ku Klux Klan members in Indianapolis. John died of “uremia and carcinoma of the prostate” on July 18, 1938, and is buried alongside his wife, Elizabeth, at Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis.

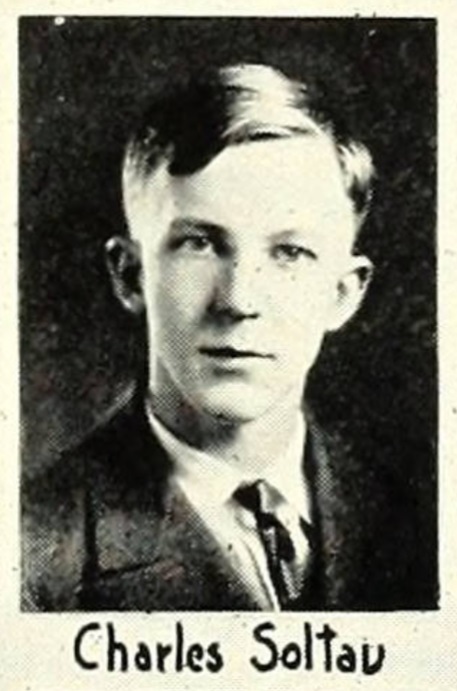

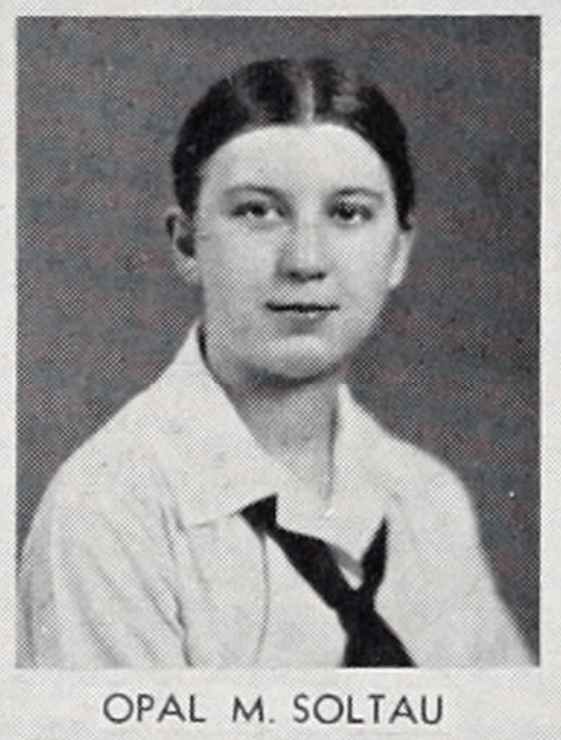

John’s eldest son, William Soltau, was a realtor who operated his agency in room 202 of the Inland Building at 160 East Market Street in the city for a quarter century. William and his wife Laura E. (Hansing) Soltau (1879-1943) were the parents of three children: Pearl Brilliance Soltau (1905-1968), Charles William Soltau (1909-1971), and Opal Margaret Soltau (1920-2008). All three children graduated from Arsenal Technical High School, Pearl, in 1922, Charles in 1926, and Opal in 1938. Pearl graduated from Butler University in 1925, Charles from Purdue in 1931 (with honors and a perfect 6.5 GPA), and Opal attended Butler University until at least 1940. The Soltau’s moved to 339 North Summit Street in 1916 and while the Soltau family was residing under that roof, it appears that all five were emersed in and sympathetic to the Nazi cause.

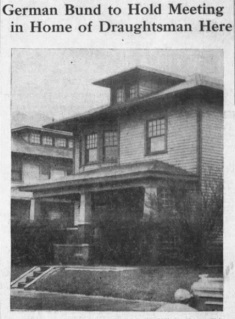

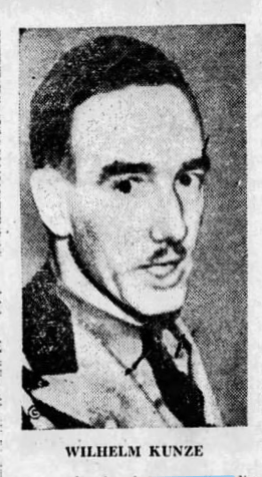

The front page of the March 9, 1938, Indianapolis News ran a photo of the Soltau House with a notice that a meeting of the German American Bund, described as a “Patriotic Fighting Organization of the German Americans”, was to be held there. Regardless, the Soltau family denied that a meeting was to be held in their home. The next day, the news ran a copy of the invitation with the address of the home and the announcement that Wilhelm Kunze, National Publicity Director of the Bund, would be the speaker and that admission was free and open to the public, especially to “All Truth-Seeking Americans”. Again, the family denied that Kunze was in the city at all, let alone scheduled to appear at the house. Kunze was fresh off his January 1938 appearance in a March of Time newsreel that the Library of Congress called “the first commercially released anti-Nazi American motion picture.” The News article announced the meeting’s date as Monday, March 14, at 8:30 pm.

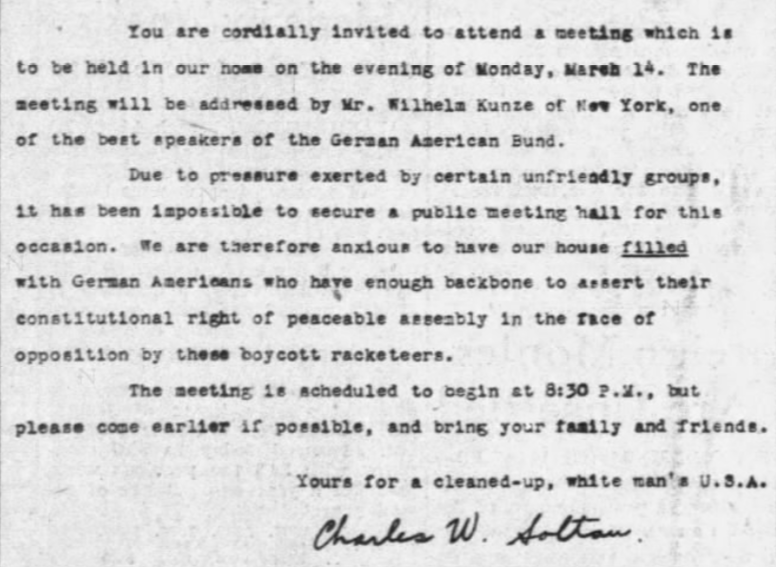

Hoosiers were shocked. After all, in February, the Athenaeum, the Liederkranz Hall (1417 E. Washington St.), and the Syrian-American Brotherhood Hall (2245 East Riverside) had all canceled the Bund’s reservation and refused to host the event. On February 25th the Indianapolis Star identified “an American-born Nazi agent…born in Indiana” attempted to secure a venue “to organize Brown Shirt Nazi units in Indianapolis.” That local organizer was revealed as Charles W. Soltau from the near-Eastside. Charles wrote a letter to the Star complaining that “the German-American Bund has been accused, maligned and condemned without a trial” and suggested that the Bund’s right to meet had been undermined by “Jewish business interests”, arguing that “a certain powerful minority group, which seems to have gained almost complete control of the press, fears the effect of public enlightment.(sic)” Charles further declared that the Soltau family was “anxious to have our house filled with German-Americans who have enough backbone to assert their constitutional right of peaceable assembly in the face of opposition by these boycott racketeers.” He closed his letter as “Yours for a cleaned-up, white man’s U.S.A. Charles Soltau.” Shortly after that revelation, 27-year-old Soltau announced that the meeting was called off.

The front page of the March 15, 1938, Indianapolis Star reported, “Rocks hurled through the windows at the home of William A. Soltau, 339 North Summit Street, broke up an organization meeting of the Indianapolis affiliate of the Nazi Amerika Deutschen Volksbundes (German American bund) late last night.” William Albert Soltau (1875-1950) called the police for help after it was learned that Gerhard Wilhelm “Fritz” Kunze (1882-1958) and a small entourage had joined the Soltau family for dinner earlier that evening. Fritz Kuhn, often referred to as the “American Führer”, was the leader of the fledgling German-American Bund (Federation). Fearing for his dinner guests’ safety, Soltau asked police to escort Kunze and his guests to safety. Although Kunze refused to divulge his identity to any of the officers present, his “tooth-brush mustache”, proper Sturmabteilung brownshirt, and swastika tie-clasp made the physical connection to German Chancellor Adolph Hitler unmistakable.

When escorted from the home, Kunze declared to the officers and crowd gathered on the sidewalk, “I am a guest of Mr. Soltau, and he does not want my name known.” Kunze eventually admitted his identity to the police after they discovered the Bund application blanks Kunze held in his hands, wrapped up in a newspaper. An Indianapolis News article claimed that visible through the broken windows were, “Fifteen chairs had been arranged around a dining room table, and on it were application blanks for Bund membership.” The article noted that the “photographer for the Associated Press was ordered off the Soltau property by a man who carried a gun.” Soltau repeated his denials that a Bund meeting had been held in his home, claiming it was just “a few guests in for dinner.” The shades of the house were drawn, and a police squad car remained in front of the house from dusk to 10:30 pm when the officers went off duty. At 10:43 pm, a barrage of rocks crashed through the north windows of the Soltau house. Cars buzzed Summit Street for days afterward as curious motorists drove past the Soltau home and a near-constant gang of 40 or 50 youngsters “milled in the neighborhood”. Further exacerbating the situation, on July 18, 1938, just 4 months after the attack at his son’s home, family patriarch and Indianapolis grocery chain magnate John Albert Soltau died at age 90. Over the years, the elder Soltau and his son had purchased 4 tracts of land totaling 234 acres along State Road 46 in Gnaw Bone, 8 miles east of Nashville in Brown County. Newspapers speculated that the land was to be used as a Bund camp for Nazi activities, but the Soltau’s denied it.

Next Week: Part II: Nazi’s at Arsenal Tech…What?

Nazi’s at Arsenal Tech…What?

Part II

https://weeklyview.net/2025/03/20/nazis-at-arsenal-tech-what-part-2/

Original publish date March 20, 2025.

On March 15, 1938, an eastside Indianapolis house was rocked (quite literally) by an angry crowd after the city learned about a formational meeting of the German-American Bund, an organization formed to follow the ideals and edicts of Adolph Hitler’s Nazi party. The Soltau family, who lived at 339 North Summit Street, welcomed a controversial visitor to their home, a German transplant named Fritz Kunze. The Nazi’s visit was greeted by Circle-City residents hurling rocks through the front windows of the Soltau home. Gerhard Wilhelm Kunze was the Bund’s publicity director who invented derogatory names for people (Franklin D. Rosenfeld) and programs (The Jew Deal) he disapproved of while extolling Jim Crow laws, warned against immigrants, and advocated for the Chinese Exclusion Act. Fritz warned white Americans: “You, Aryan, Nordic, and Christians…wake up” and “demand our government be returned to the people who founded it…It has always been very much American to protect the Aryan character of this nation.”

Despite the Eastside Indianapolis Nazi recruitment session debacle, the Soltau family stayed committed to Nazi ideology. In November 1938, Charles and his youngest sister, Opal, fresh off her graduation from Tech High School, returned from a Bund indoctrination trip to Germany. Some of these trips included meetings with Joseph Goebbels, Heinrich Himmler, and Hitler himself. Whether the siblings were in the Rhineland to attend a German youth camp or to enjoy a post-graduation vacation is unknown. While 18-year-old Opal fit the profile, Charles was almost 30 and may have aged out of that group. They left Hamburg on November 3rd, arriving back in New York on the 11th. The Soltau family quietly supported the Bund cause by subscribing to The Free American newsletter and other Nazi propaganda publications including a liturgy of anti-Semitic tracts like The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and Hitler’s Mein Kampf manifesto. A November 1941 FBI investigation identified the Soltau family as 4 of 38 stockholders in the Press (The publishing house had issued 5000 shares of preferred stock at $10 a share in 1937). The FBI noted that the Soltau family were the only stockholders from Indiana. While the Free American had local news columns in Fort Wayne and South Bend, there were none in Indianapolis.

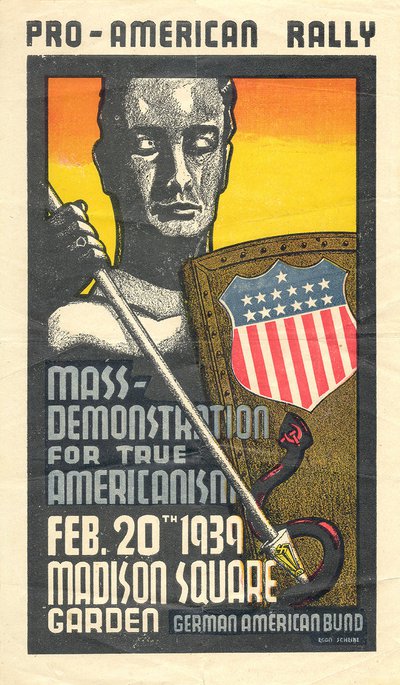

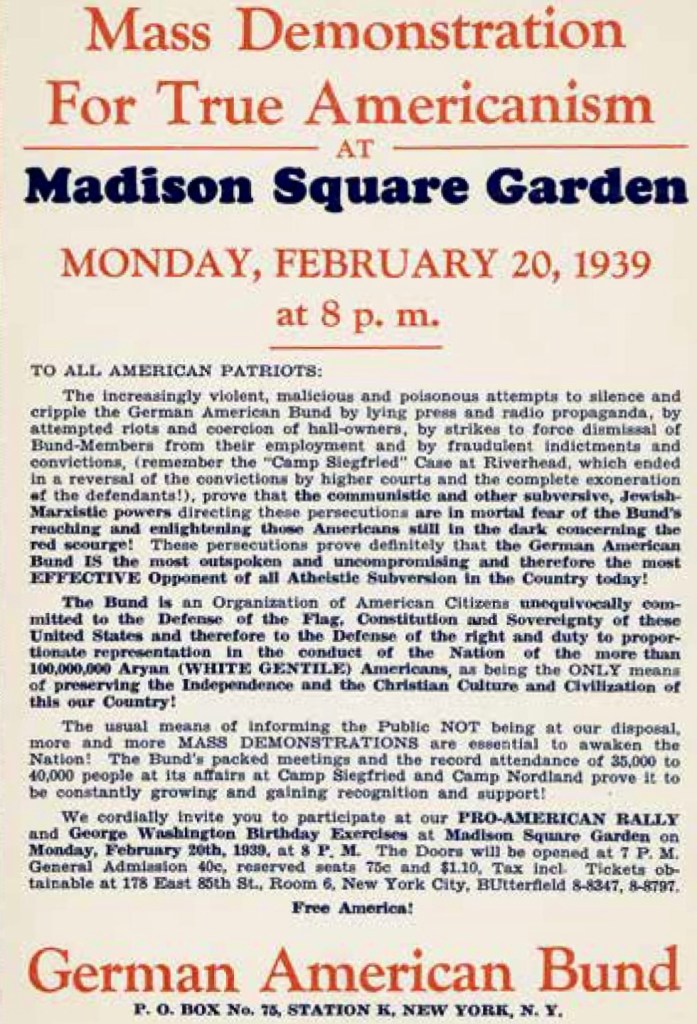

The German-American Bund was at its zenith in 1938-39, but after 20,000 people attended a Bund rally at Madison Square Garden in February 1939, New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia instigated a series of investigations that would ultimately bring them down. In September 1939, after the Nazis invaded Poland the FBI and federal government went after the Bund. Fritz Kunze was detained by the South Bend Police on May 12, 1941.

In the inventory of Kunze’s papers confiscated by the Police were cards with the names and addresses of Bund members, including the Soltau family, the only members from Indiana. Kunze was charged with espionage, and in November 1941, just a month before Pearl Harbor, he fled to Mexico, hoping to escape to Germany. Kunze was captured by the Feds in Mexico in June 1942 and sent to jail for espionage, where he spent the rest of the war. The German-American Bund disbanded officially immediately after Pearl Harbor. Regardless, some Bund members had their American citizenship revoked and were deported, while others were prosecuted for refusing to register for the draft. Kunze was eventually deported himself in 1945.

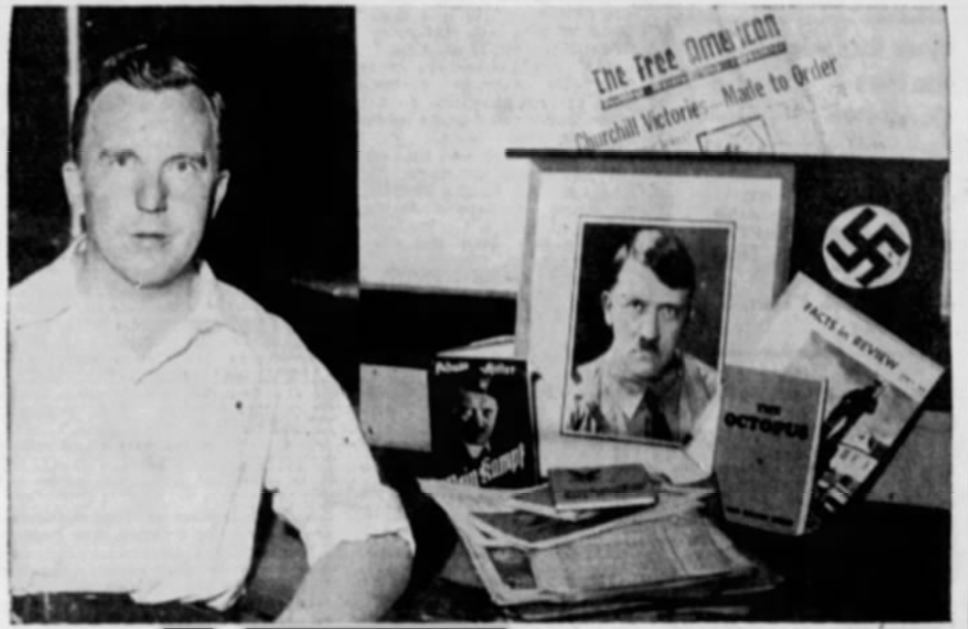

In September 1940, when the draft began, the Bund instructed its members to boycott registration, and soon, former Bundist members began to be prosecuted by the Selective Service System for failure to register. 33-year-old Hoosier Charles William Soltau was among those who refused to report for induction. In August 1942, draft dodger Soltau was arrested, and his home was raided by US Marshals who discovered a large cache of Nazi propaganda there. It included issues of The Free American, a portrait of Hitler, Swastika banners, and Nazi memorabilia. In a four-page letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Soltau argued that “in all my association with the German-American Bund I never was guilty of any subversive activity.” After spending a couple of nights in jail, Soltau posted a $5000 cash bond. When he appeared in court in November, he argued that, “My conscience will not permit me to bear arms against the German people.” He informed the court that “This war is a war of aggression by the United States against the Germans. I am a man of German blood, and I don’t think it is right or fair or just for a man of German blood to bear arms against the German people.” It took the jury six minutes to deliberate and deliver a five-year sentence to Soltau. Judge Robert C. Baltzell concluded that “I have never seen a more contemptuous fellow in this court,” and “I am going to do all I can to see that you serve as much [time] as possible.” In December 1943, while serving his sentence at the Federal Correctional Institute in Milan, Michigan federal prison, Soltau’s mother Laura died. Charles was released in 1946, and with his sisters, Opal and Pearl, he moved to their secluded Brown County property near Gnaw Bone.

Their father, William Albert Soltau, died there on October 6, 1950, at age 75. His funeral service was held at Shirley Brothers Central Chapel in Irvington, and he is buried at Memorial Park Cemetery on Washington Street alongside his brothers, whose funeral services were also held at Shirley Brothers. At least one brother, Benjamin Harrison “Ben” (1889-1963), was a member of Irvington Masonic Lodge 666, and another, James Garfield Soltau (1881-1932), was an admitted member of the KKK. The Soltau siblings quietly left Indianapolis and moved to Gnaw Bone, where they lived together in Brown County for the remainder of their lives, and none of the three ever married. The siblings started with three goats in 1952, and by 1962, their “trip” (or tribe) had reached 44 head, so they created Pleasant Valley Goat Farm on their 200-acre Gnaw Bone property. The family sold goat’s milk and yogurt in local farm markets. Pearl Soltau also moonlighted as an accountant for a local hosiery mill, preparing tax returns on the farm. After a two-year illness, Pearl died at the Gnaw Bone farm in May 1968 at the age of 62. Charles died there on July 5, 1971, at age 61. Although Charles’s membership in the “German-American National Congress” was mentioned in his obit, Pearl betrayed no history of continued xenophobic activism after the war. Both are buried at Henderson Cemetery in Gnaw Bone.

However, the youngest sibling, Opal, remained committed to neo-Nazi causes for more than a half-century after the war. Even after the deaths of her siblings, Opal continued to agitate for unpopular political causes. Opal had been a standout at Arsenal Tech High School. She was a straight-A Honor Roll Student and received the scholarship medal from the Tech faculty in 1938. In the 1980s, Opal Soltau was accused of mailing neo-Nazi propaganda from the post office in Nashville, In. In September 1996, Opal sold her parcel of 120 acres in Brown County and by January 1997, she had moved to Nebraska. That same month, she became a Director for the National Socialist German Workers’ Party-Overseas Organization. Opal Soltau died in Lincoln in August 2008 and is presumed buried there. No one knows how the pilot light of Nazi fervor was lit in the Soltau family and, for that matter, how it burned out of control within the hearts and minds of these three Arsenal Tech graduates. Political ideology grows unchecked when surrounded only by like-minded individuals living in a silo of misinformation. Sometimes, it is the better part of valor to explore divergent opinions. The flame of Nazism burns through everything it touches. Characterized by extreme nationalism and steered by blind faith in misguided authoritarianism, its victims don’t realize what has happened until it’s too late. And by then, no matter what, they will never admit that they were ever wrong in the first place.

For a more thorough study of the Soltau family, I recommend the blog Nazis in the Heartland: The German-American Bund in Indianapolis by the late Paul R. Mullins (1962-2023), Anthropology Professor at IU Indianapolis (formerly IUPUI).

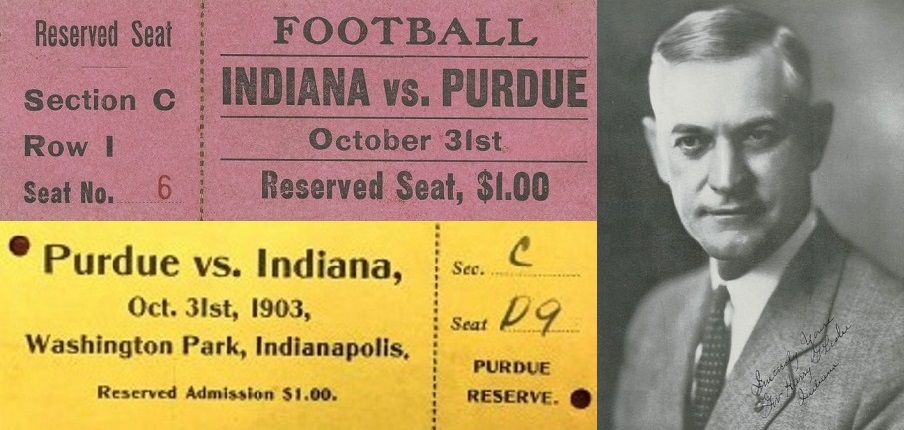

A total of 17 people died immediately, including 13 players, a coach, a trainer, a student manager and a booster. One member of the team miraculously landed on his feet and was unharmed after being thrown out a window. All the casualties were limited to the team’s railcar. Twenty-nine more players were hospitalized, several of whom suffered crippling injuries that would last the rest of their lives. Further tragedy was averted when several people, led by the “John Purdue Special” brakeman, ran up the track to slow down the second special train that was following 10 minutes behind the first. This heroic action undoubtedly saved many lives by preventing another train wreck. One of the survivors of the wreck was Purdue University President Winthrop E. Stone who remained on the scene to comfort the injured and dying.

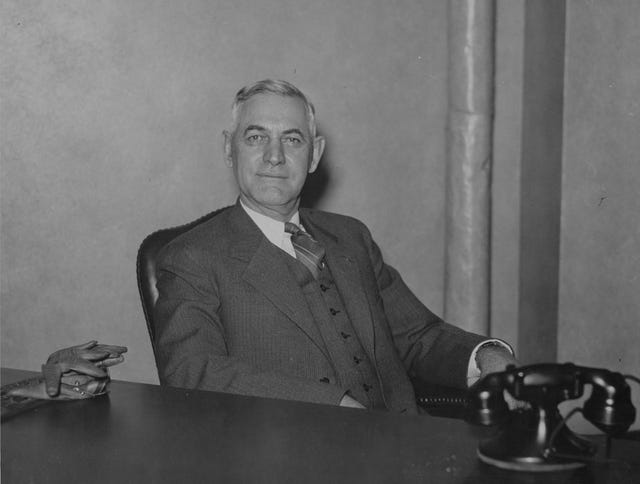

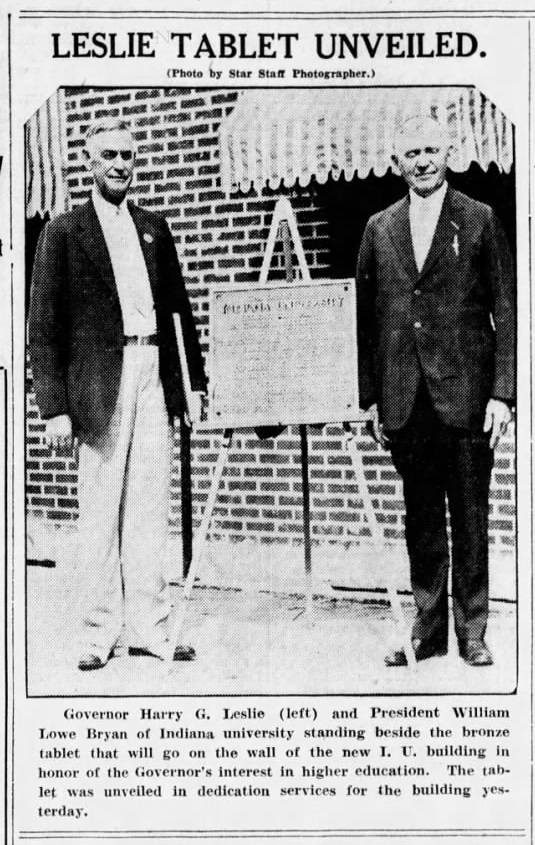

A total of 17 people died immediately, including 13 players, a coach, a trainer, a student manager and a booster. One member of the team miraculously landed on his feet and was unharmed after being thrown out a window. All the casualties were limited to the team’s railcar. Twenty-nine more players were hospitalized, several of whom suffered crippling injuries that would last the rest of their lives. Further tragedy was averted when several people, led by the “John Purdue Special” brakeman, ran up the track to slow down the second special train that was following 10 minutes behind the first. This heroic action undoubtedly saved many lives by preventing another train wreck. One of the survivors of the wreck was Purdue University President Winthrop E. Stone who remained on the scene to comfort the injured and dying. Walter Bailey, a reserve player from New Richmond, was grievously injured but refused aid so that others could be helped before him. Bailey would die a month later at the hospital from complications from his injuries and massive blood loss. Purdue team Captain Harry “Skeets” Leslie was found with ghastly wounds and covered up for dead. His body was transported to the morgue with the others. Leslie would later be upgraded to “alive” when, while his body lay on a cold slab at the morgue, someone noticed his right arm move slightly and he was found to have a faint pulse. Skeets was clinging to life for several weeks and needed several operations before he was out of the woods. Leslie would later go on to become the state of Indiana’s 33rd governor, the only Purdue graduate to ever hold that office. As a reminder of that Halloween train disaster, Skeets would walk with a limp for the rest of his life.

Walter Bailey, a reserve player from New Richmond, was grievously injured but refused aid so that others could be helped before him. Bailey would die a month later at the hospital from complications from his injuries and massive blood loss. Purdue team Captain Harry “Skeets” Leslie was found with ghastly wounds and covered up for dead. His body was transported to the morgue with the others. Leslie would later be upgraded to “alive” when, while his body lay on a cold slab at the morgue, someone noticed his right arm move slightly and he was found to have a faint pulse. Skeets was clinging to life for several weeks and needed several operations before he was out of the woods. Leslie would later go on to become the state of Indiana’s 33rd governor, the only Purdue graduate to ever hold that office. As a reminder of that Halloween train disaster, Skeets would walk with a limp for the rest of his life.