Original publish date January 26, 2023. https://weeklyview.net/2023/01/26/wendell-ladner-the-abas-brawling-burt-reynolds-part-2/

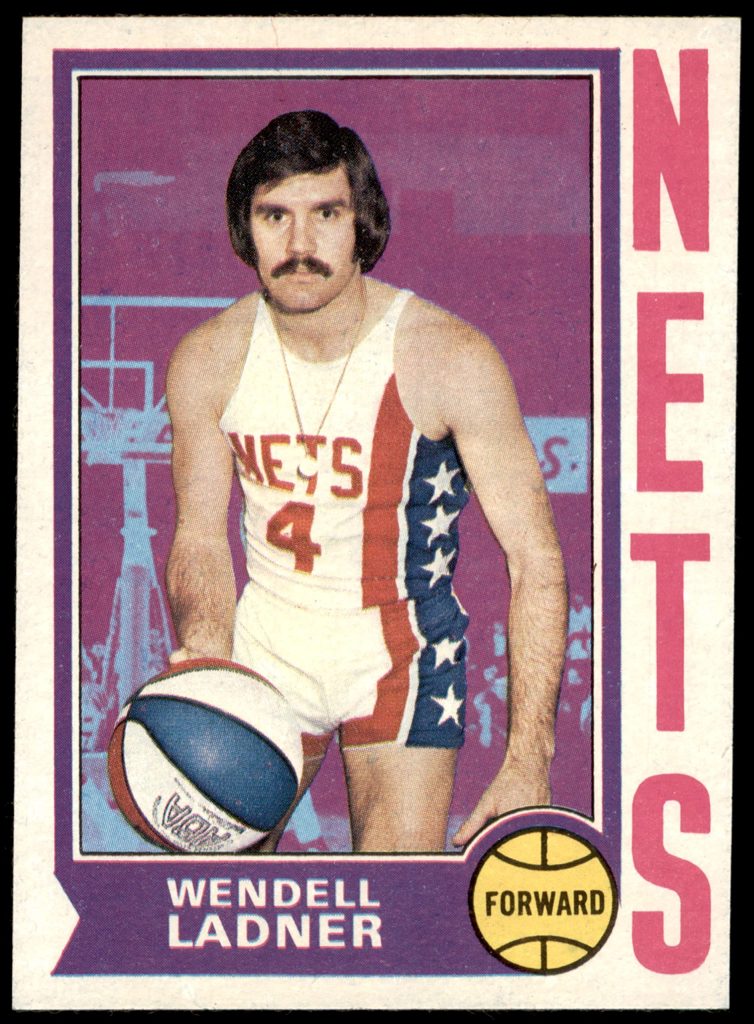

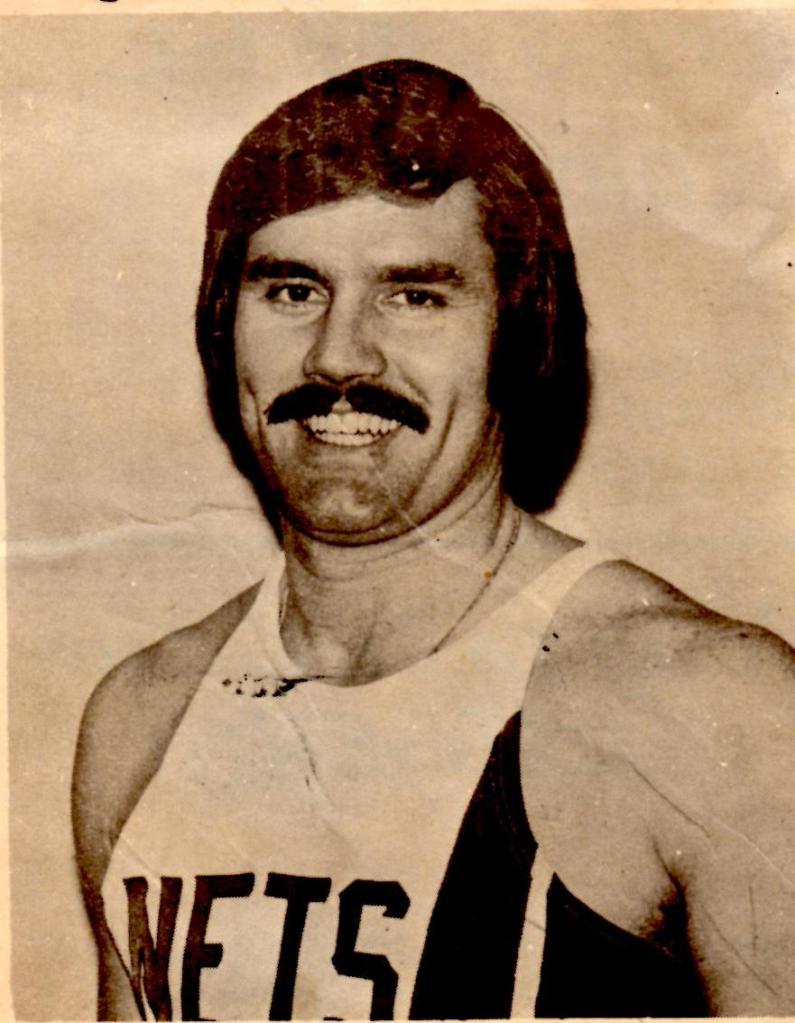

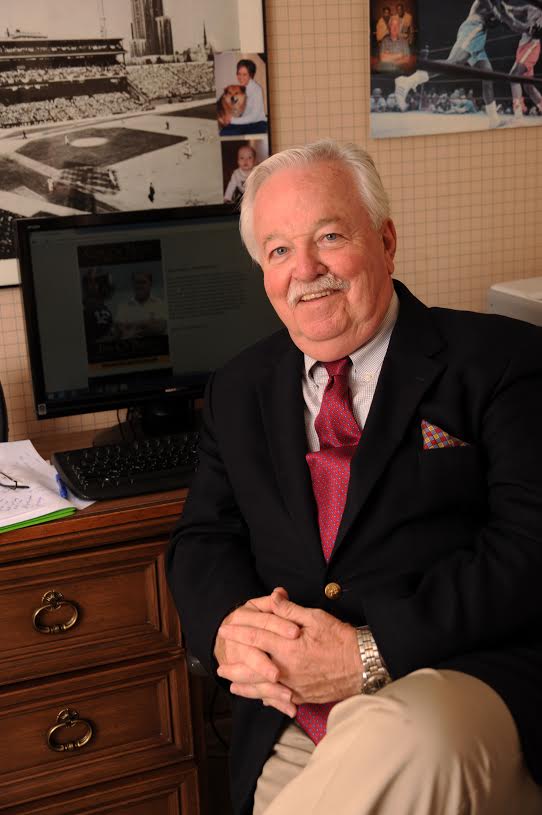

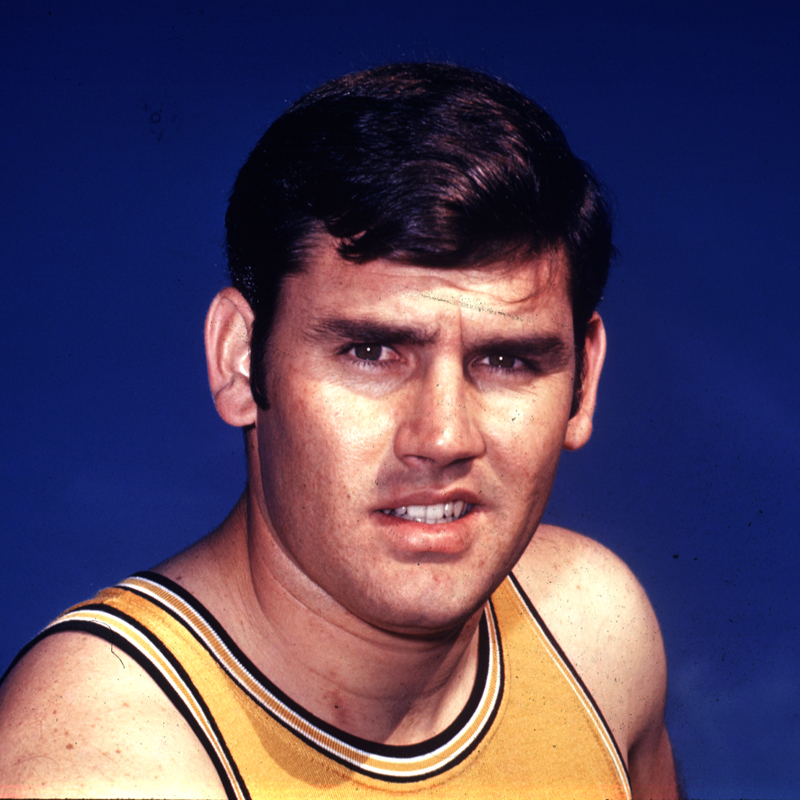

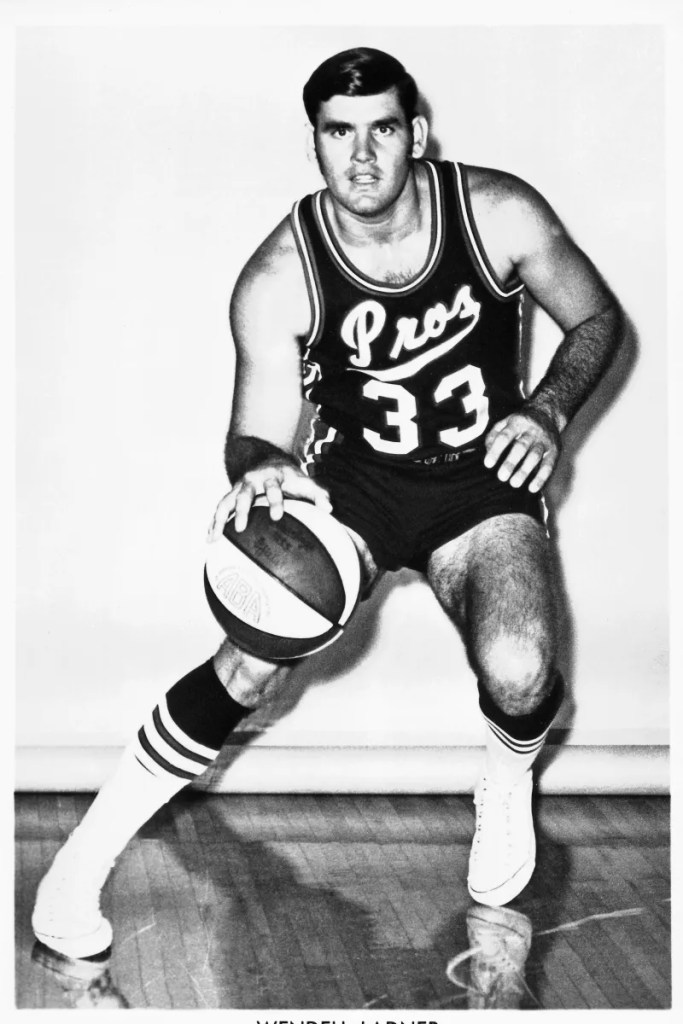

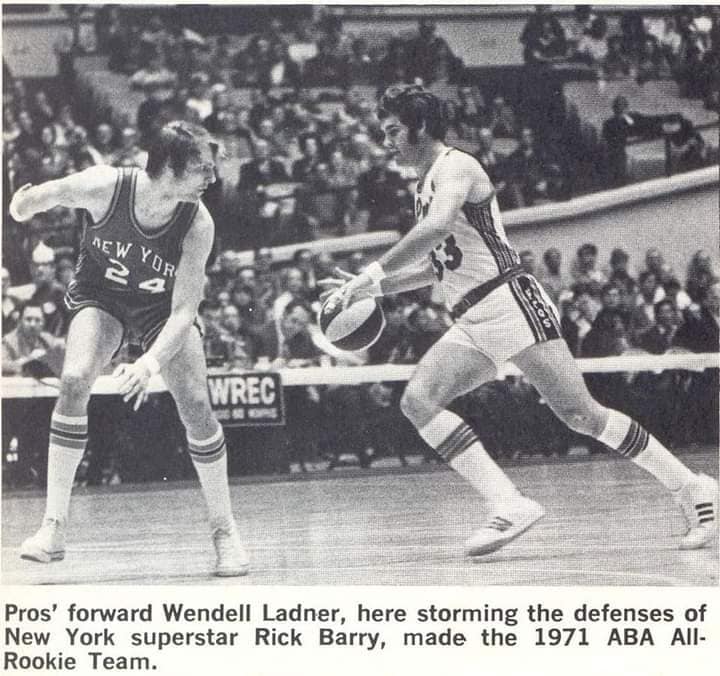

I grew up a gym rat. I’ve mentioned before how my parents used to take me down to the Fairgrounds, drop me off at the player entrance at the State Fairgrounds Coliseum, and leave me there for an hour or so while they traveled over to the TeePee Restaurant for pie and coffee. That’s when this reporter, then a 10-year-old with a Hollywood burr, first encountered a muscular, burly 6-foot-5, 220-pound guy who was a dead ringer for Burt Reynolds. His name was Wendell Ladner, and even though for much of his career he wasn’t even a starter, he always hustled, threw himself after any loose ball, and elbowed his way to every rebound. He was an important cog for a New York Nets team that won an ABA championship and a Kentucky Colonels team that thumped up on my beloved Indiana Pacers often enough that I held a grudge. But he was always nice enough to stop, smile, and talk for a minute to a shy buck-toothed kid when I asked him for an autograph.

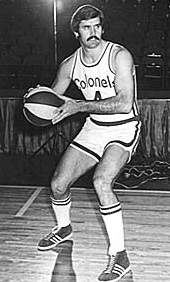

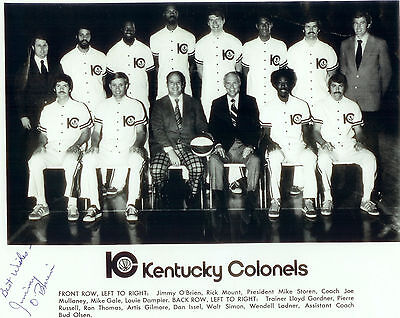

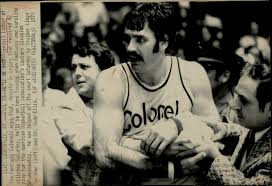

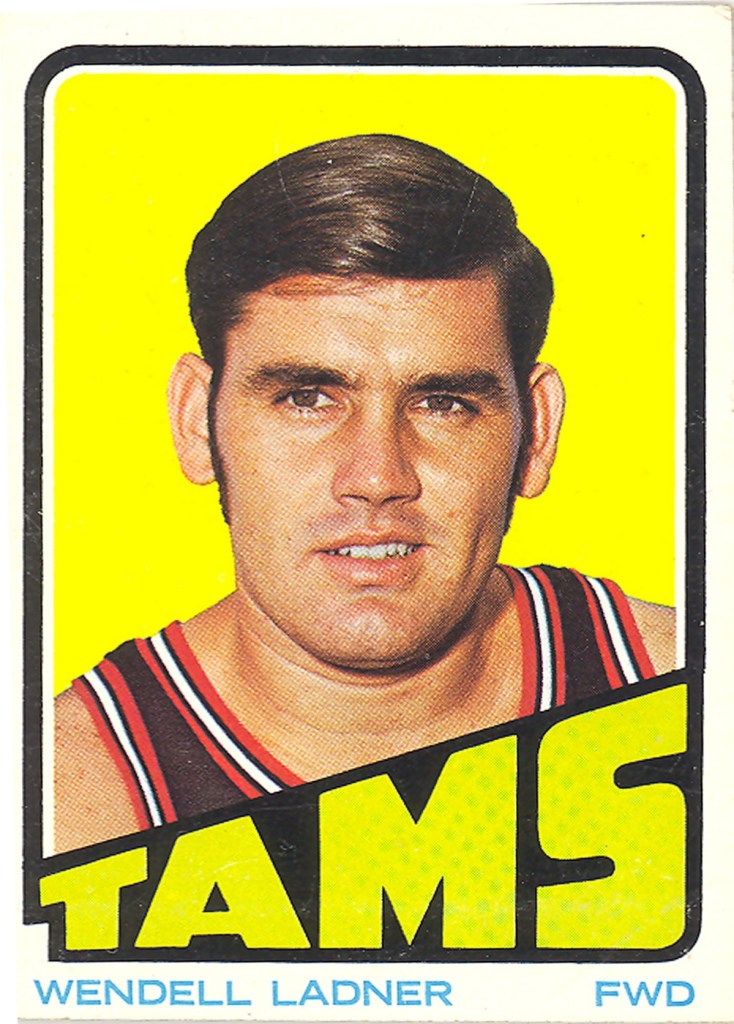

Things changed for Wendell Ladner midway between the 1972-73 season when he joined Southport High School’s “Little” Louie Dampier, “The Horse” Dan Issel, and the “A-Train” Artis Gilmore as a member of Pacer’s arch-rival Kentucky Colonels. His numbers weren’t his best with the Colonels, falling to 7.3 ppg and 4.9 rpg the first season and 9.9 ppg and 7.9 rpg that second season. Despite those numbers, he quickly became one of the most popular players on the Colonels roster — “expecially” with the ladies. However, if you were ever privileged enough to see a Pacers vs. Colonels game in person back then, you know that Colonels fans are tough. So Wendell had to win the male fans over first.

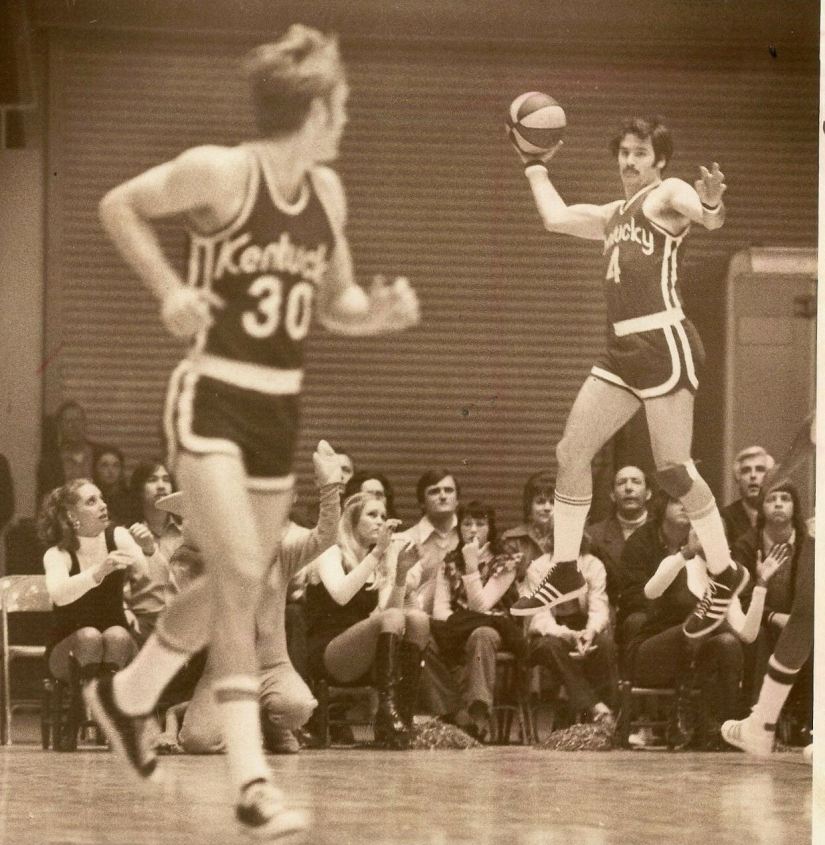

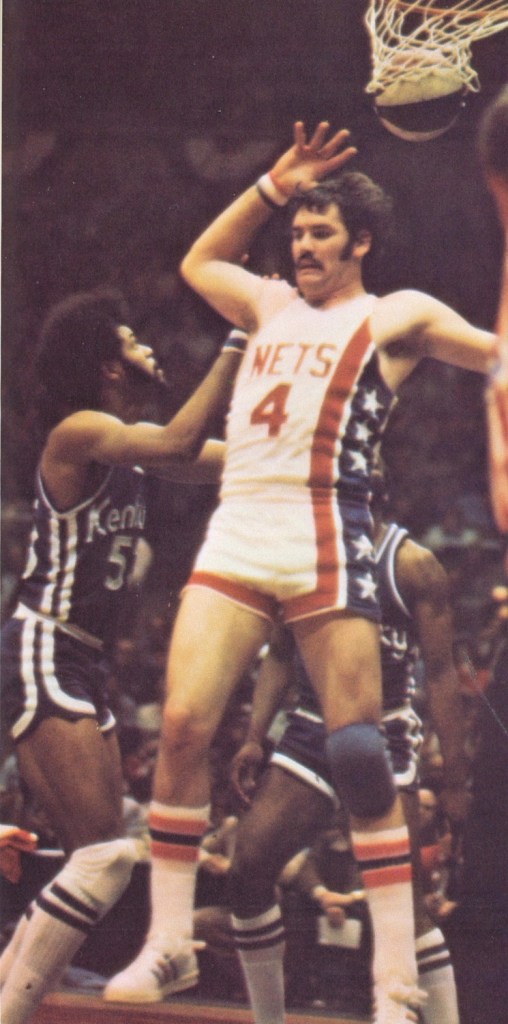

Today, they would call Wendell Ladner a “defensive specialist” for the Colonels. But what that really meant was Ladner was an enforcer whose job it was to hack the hell out of anyone who dared foul Dan Issel or Artis Gilmore. He was involved in more than one Pacers fistfight during his tenure with the Colonels. While fight stats in the ABA were never kept, I would be willing to bet that Ladner got in a “spirited scuffle” with players on every team in the league. Rumor has it that the Dallas Cowboys once invited Ladner to try out for the team. Colonels minority owner Bill Boone called him “the toughest SOB I’ve ever seen . . . a rebounding fool and hatchet man.”

During the 30th ABA reunion in 1997, Bob Netolicky and I traveled down to do a radio show in Louisville with longtime Colonels trainer Lloyd “Pink” Gardner. After the show, we retreated to the radio station breakroom for some after-hour storytelling. Pink was the team trainer for all nine seasons of the ABA (1967-1975) so he knew everyone. He remembered Wendell’s habit of fussing over his hair constantly. Pinky said, “Wendell had a habit of never adding the ‘ed’ suffix to his words when he talked. He’d say things like ‘I don’t want to get my hair all mess up.’ or ‘I’m going out tonight so I gotta get all dress up.’ One night Ladner had a terrible game, lost us the game actually. Dan Issel came into the locker room and saw Wendell primping in the mirror with his hairbrush getting ready to scoot out for a hot date. Dan yelled, ‘Watch out everybody, Wendell’s game was all foul up so don’t say nothin’ to him or you’ll get him all peeve off.’ (Only Issel didn’t say foul or peeve if you know what I mean.) Next thing you know Issel and Ladner were throwing punches while the whole locker room was rolling on the floor laughing.”

In his book Kentucky Colonels: Shots from the Sidelines, Pink explained: “Wendell always played with reckless abandon, always diving after loose balls, jumping over press tables, always hoping that he would come down in the lap of some beautiful lady.” Pink recalled one game “with 3:09 left in the game and the Colonels with a sizable lead, Wendell went airborne over the Cougars bench, crashing into a five-gallon glass water cooler.” The bottle smashed to the floor and Wendell landed on the shards of broken glass. He jumped up quickly and tried to get back to the floor, but the trainer stopped him because he was bleeding profusely from gashes in his arm. Pink continued, “He wanted to go back out and play. Dr. Rudy Ellis said no. We took him to the hospital and stitched him up, 37 stitches in all.

It was April 21st, 1973, game 6 of the ABA Eastern Division finals against the Carolina Cougars at Freedom Hall and the Cougars were up in the series 3 games to 2. Play was stopped while Wendell was led to the locker room dripping in blood while the crowd watched in stunned silence. Thirty minutes later, here comes Ladner sprinting back to the bench, a bandage encasing his left forearm. The Colonels were losing and Ladner begged to re-enter the game, but sanity prevailed and Mr. Excitement was placed at the end of the bench for his own protection.” Pink noted, “but Wendell never missed a practice or game.” Kentucky would win that game and then another to take the series. But they lost the ABA Championship to the Indiana Pacers 4 games to 3. The Pacers became the first team to win a third ABA championship while the Colonels became the first team to lose two separate ABA championship series. Complete disclosure: The Pacers would eventually lose two, too.

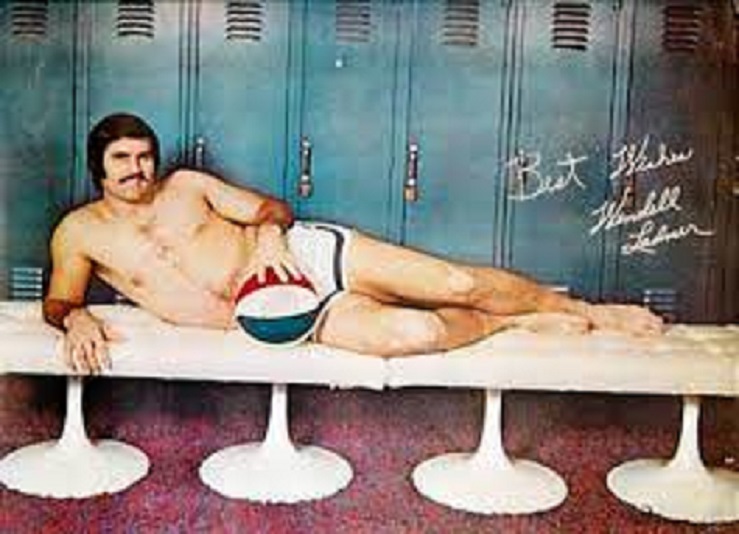

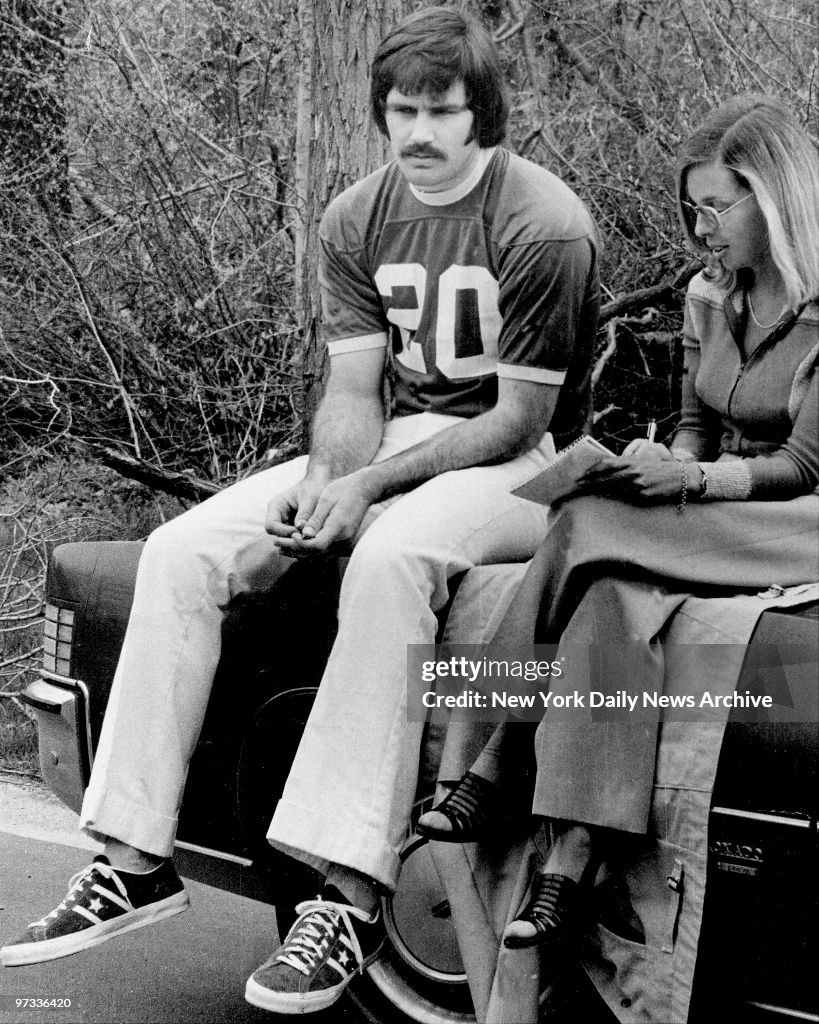

Also in 1973, Wendell pulled off the stunt he is most remembered for to this day. Ladner did his best imitation of Burt Reynolds infamous Cosmopolitan magazine nude pose in a shirtless beefcake poster that sold out in hours. Wendell is posed stretched out on the Colonels’ locker room bench at Freedom Hall in Louisville wearing only his “tighty-whitey” home uniform trunks (players didn’t wear the baggy trunks they wear today) with a Red, White, & Blue ABA basketball strategically positioned to hide his naughty bits. Ladner flashed a million-dollar smile for the female Colonel faithful. Oh, and the poster has a “Best Wishes” facsimile autograph in the upper right corner. After that poster came out, Ladner really played up to that image. During timeouts, women jockeyed for position behind the Colonels bench to giggle and shout sweet nothings to their favorite as he brushed the hair away from his eyes and smiled back at them.

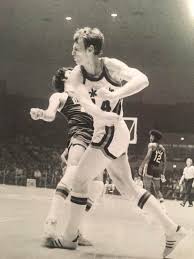

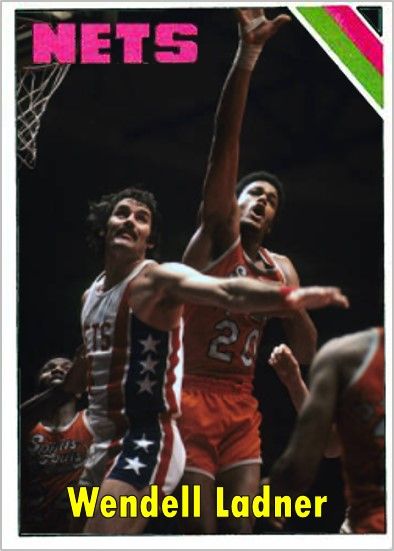

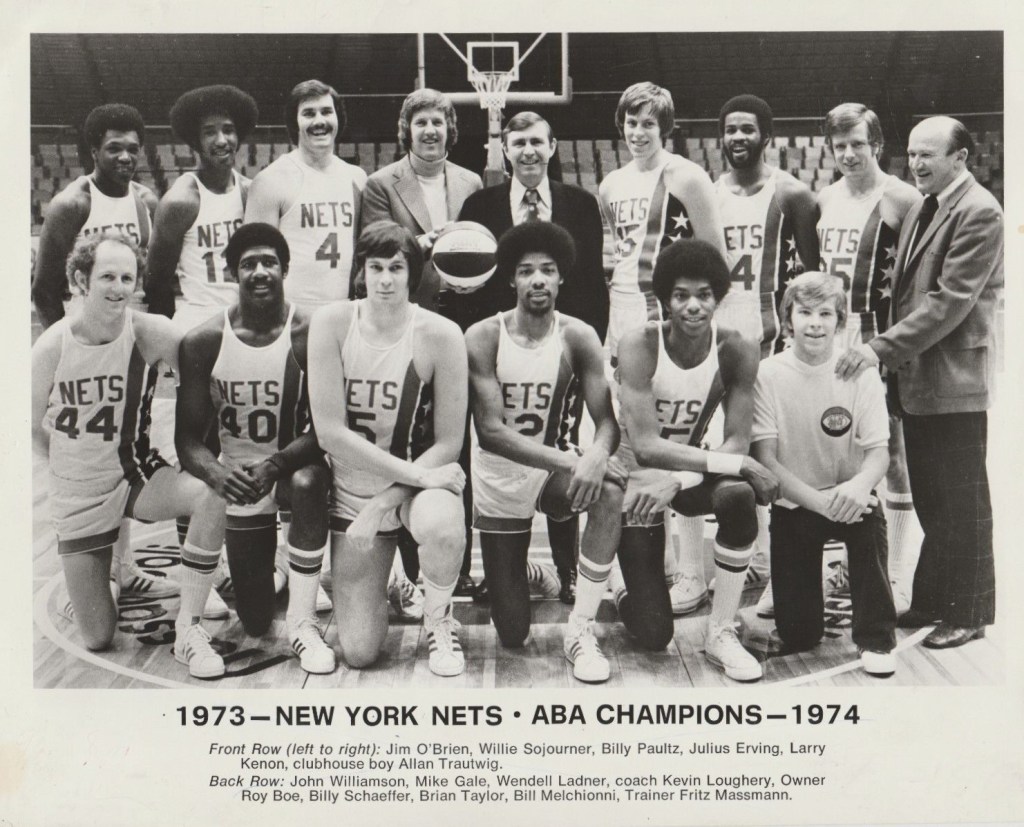

The next season (January of 1974), Ladner was traded to the New York Nets, a trade KFC magnate and Colonels owner John Y. Brown, Jr. later said he regretted. The Colonels traded Ladner and Mike Gale to the Nets for John Roche, pronounced “Ouch” by Colonels fans. At the time of the trade New York trailed Kentucky in the Eastern Division standings, but after adding Ladner, the Nets surged past the Colonels to win the Eastern Division championship and the 1974 ABA championship beating his old team. During that series, Ladner and his old teammate Dan Issel exchanged punches in one game: Issel wound up with three stitches under one eye.

Former ABA Virginia Squires and Cincinnati Reds broadcaster Marty Brennaman called it “the worst trade ever in professional basketball.” Maybe not the worst pro basketball trade ever, but it sure was a bad one. The next year, Little Louie Dampier busted his hand wide open during a game and asked Colonels team doctor Rudy Ellis to stitch up his hand “in a hurry so I can get back into the game” to which the Doctor replied, “I thought Wendell Ladner was the only person that crazy.” In New York, Ladner’s job with the Nets was to protect Julius Erving. Dr. J called Wendell his wackiest teammate ever because “he wanted to be Burt Reynolds with a basketball”.

After winning his one and only ABA Championship, on June 24, 1975, Ladner boarded Eastern Air Lines Flight 66 from New Orleans to New York City. The plane, a Boeing 727 trijet tail number N8845E, departed from Moisant Field (Louis Armstrong International Airport today) without any reported difficulty at 1:19 PM EDT with 124 people on board, including 116 passengers and a crew of 8. A severe thunderstorm hit JFK airport just as Flight 66 was approaching the New York City area. At 3:52, the approach controller warned all incoming aircraft that the airport was experiencing “very light rain showers and haze” with zero visibility and that all approaching aircraft would need to perform instrumental landings. At 3:53, Flight 66 was approaching Runway 22L. 6 minutes later, the controller warned all aircraft of “a severe wind shift” on the final approach, the aircraft encountered a microburst or wind shear environment caused by the severe storms.

The plane continued its descent until it began striking the approach lights approximately 2,400 feet from the start of the runway. Upon the first impact, the plane banked to the left. It continued striking the approach lights until it burst into flames and scattered the wreckage along Rockaway Boulevard, which runs along the northeast perimeter of JFK airport. Of the 124 people on board, 107 passengers and six crew members (including all four flight crew members) were killed. The other 11 people on board, including nine passengers and two flight attendants, were injured but survived. Wendell Ladner was not among them.

Ladner died at the age of 26. His body was identified by medical examiners only because he was wearing his charred Nets ABA championship ring. At the time, the crash was the deadliest in United States history. For many years, the Nets included his name and uniform number in their list of retired numbers, though Ladner’s No. 4 did not hang in the rafters with the other retired numbers. Out of respect to Ladner, Fritz Massmann, Nets trainer from 1970 to 1992, never issued No. 4 to any other player for 17 years after Ladner’s death. When Fritz retired, the New Jersey Nets issued Wendell’s number 4 to Rick Mahorn which he wore for the next 4 years.

Wendell Ladner finished his 300-game ABA career with 3,474 points and 2,481 rebounds. He also played in 40 ABA playoff games and a pair of ABA all-star games. Ladner also has a road in Perkinston, Mississippi, named after him in his honor. The crash of Flight 66 led to the development of the first low-level wind shear alert system by the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration in 1976. The accident also led to the discovery of downbursts, a weather phenomenon that creates vertical wind shear and poses dangers to landing aircraft, which ultimately sparked decades of research into downburst and microburst phenomena and their effects on aircraft. ABA fans might find it ironic that the term for the natural phenomenon that took Wendell Ladner’s life became known as a microburst. If Mother Nature had nicknamed this masculine mauler from the Magnolia State herself, she quite likely would have reserved the name microburst for him. Because, make no mistake about it, Wendell Ladner was a true force of nature.

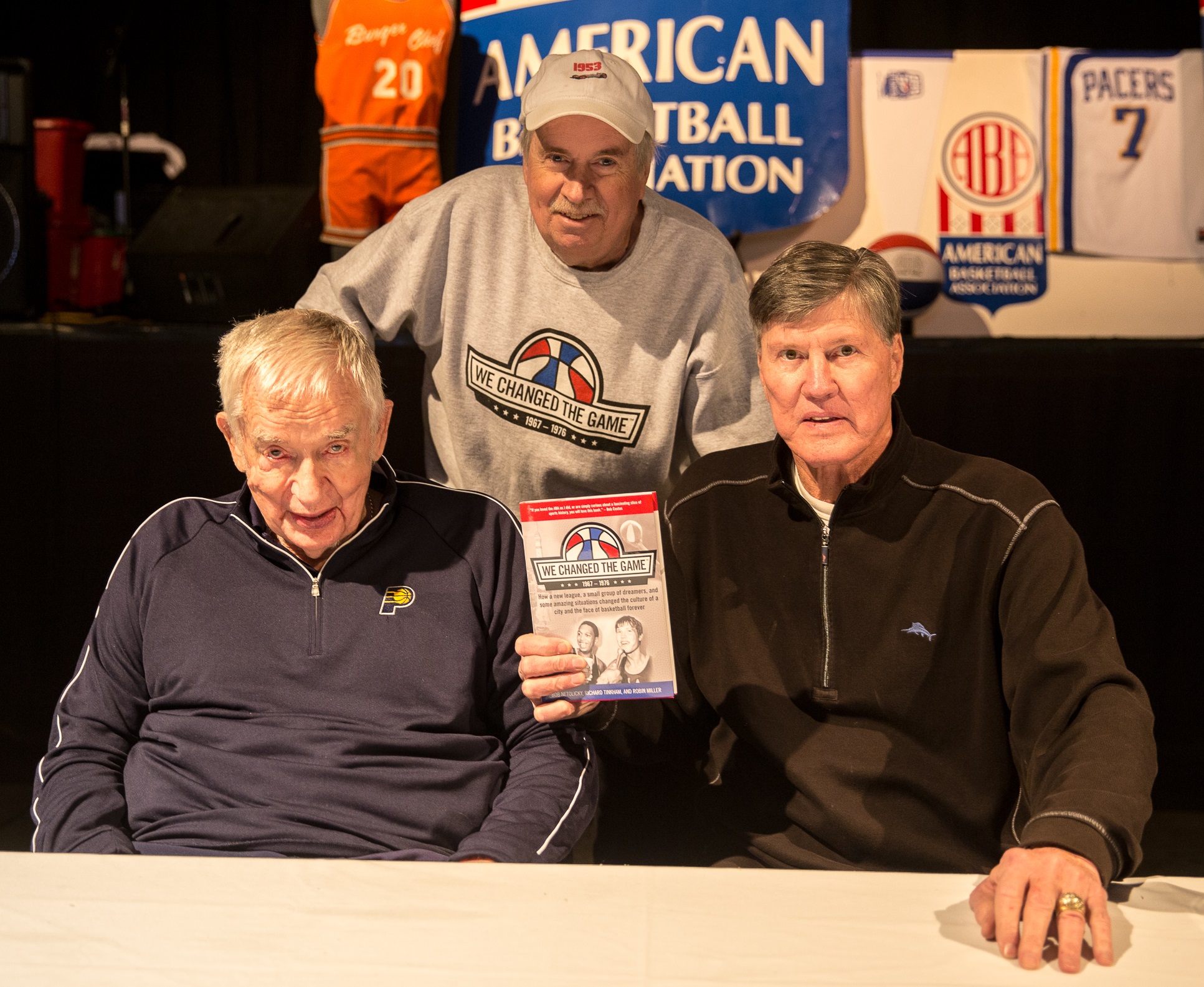

![ABA 50th_BLF[2]](https://alanehunter.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/aba-50th_blf2.png) On Saturday, April 7th, Indianapolis will host the 50th reunion celebration of the ABA with an evening banquet at Banker’s Life Fieldhouse and a special daytime public event at Hinkle Fieldhouse from 11:00 to 3:00. The public is invited to attend this once in a lifetime event that will include a special ABA 50th anniversary ring presentation for all the players followed by a Guinness World Book of Records attempt to set the mark for most pro athletes signing autographs in a single session.

On Saturday, April 7th, Indianapolis will host the 50th reunion celebration of the ABA with an evening banquet at Banker’s Life Fieldhouse and a special daytime public event at Hinkle Fieldhouse from 11:00 to 3:00. The public is invited to attend this once in a lifetime event that will include a special ABA 50th anniversary ring presentation for all the players followed by a Guinness World Book of Records attempt to set the mark for most pro athletes signing autographs in a single session.