Original Publish Date February 20, 2025.

https://weeklyview.net/2025/02/20/the-genesis-of-bob-dylan-part-1/

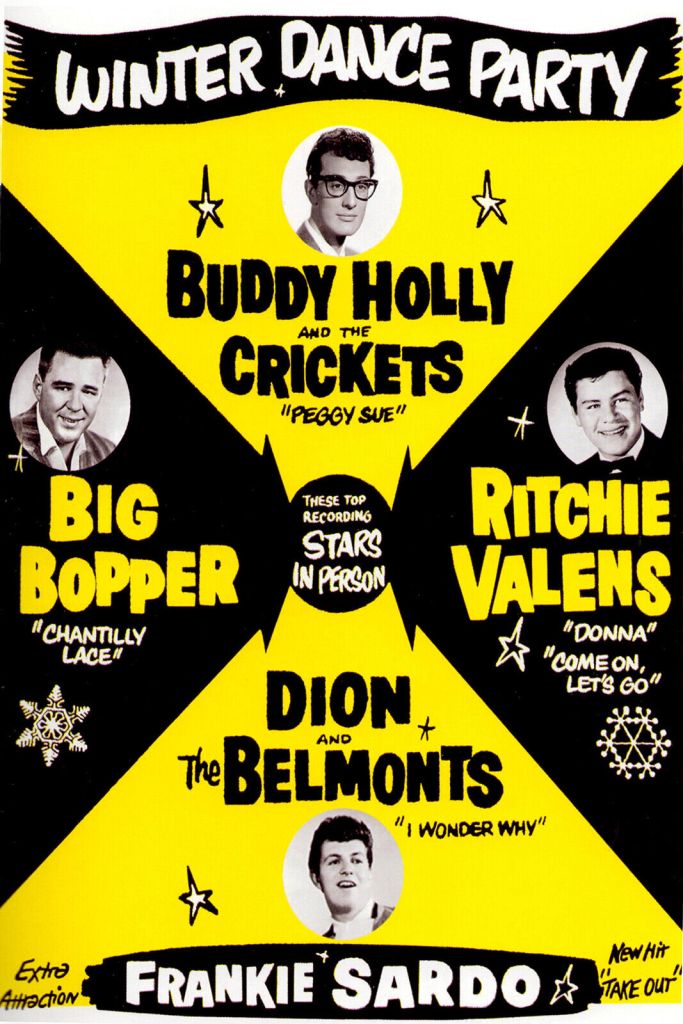

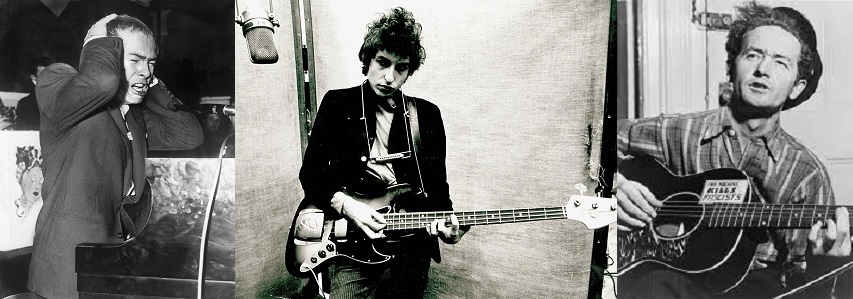

Another sad anniversary passed recently. On February 3, 1959, rock and roll pioneers Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and “The Big Bopper” J. P. Richardson were all killed (along with pilot Roger Peterson) in a plane crash near Clear Lake, Iowa. The event became known as “The Day the Music Died” after Don McLean memorialized it in his 1971 song “American Pie.” While the anniversary passes every year, every so often they put us in a reflective mood. This year’s anniversary observance came on the heels of my 2-part article on the tragic death of Hattie Carroll, a subject that serrated Bob Dylan’s soul.

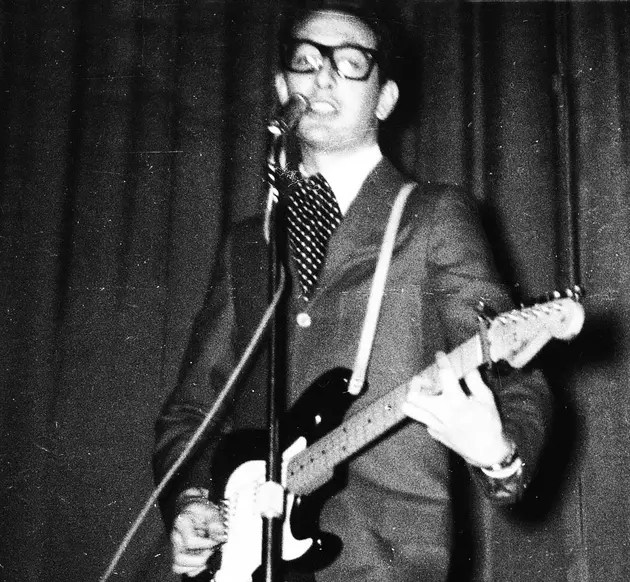

It turns out the Clear Lake plane crash had an equal impact on him, but for this one, Dylan had a front-row seat. On January 31, 1959, 18-year-old Robert Allen Zimmerman was in the crowd when Buddy Holly brought his ill-fated “Winter Dance Party” tour to Dylan’s Duluth Minnesota hometown. Holly, Valens, and the Big Bopper (along with Waylon Jennings and Dion and the Belmonts) came to the National Guard Armory in that city nine days into a grueling 24-date barnstorming tour of small ballrooms and theatres of the midwest in the dead of winter. While the tour was scheduled to go as far south as Chicago, Cincinnati, and Louisville, it did not include any Indiana stops.

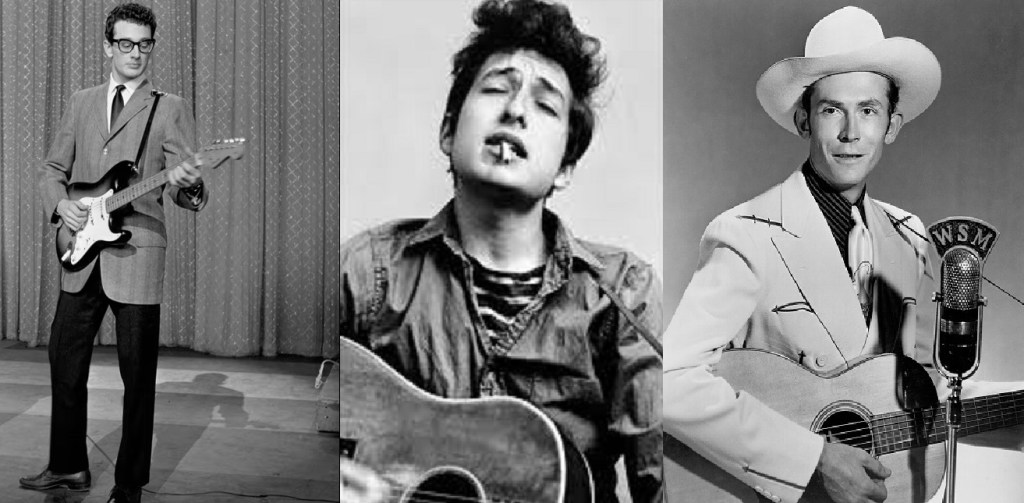

In June 2017, after being honored with the Nobel Prize for Literature, the famously enigmatic Dylan reflected on his earliest influences. As you may imagine, Dylan singled out three books specifically: Moby Dick, All Quiet on the Western Front, and The Odyssey before reflecting on Buddy Holly and how that night started him on his musical journey. “If I was to go back to the dawning of it all, I guess I’d have to start with Buddy Holly. Buddy died when I was about 18 and he was 22. From the moment I first heard him, I felt akin. I felt related like he was an older brother. I even thought I resembled him.” Dylan continued, “Buddy played the music that I loved, the music I grew up on country western, rock and roll, and rhythm and blues. Three separate strands of music that he intertwined and infused into one genre. One brand. And Buddy wrote songs, songs that had beautiful melodies and imaginative verses. And he sang great, sang in more than a few voices. He was the archetype, everything I wasn’t and wanted to be.”

“I saw him only but once, and that was a few days before he was gone,” Dylan recalled. “I had to travel a hundred miles to get to see him play, and I wasn’t disappointed. He was powerful and electrifying and had a commanding presence. I was only six feet away. He was mesmerizing. I watched his face, his hands, the way he tapped his foot, his big black glasses, the eyes behind the glasses, the way he held his guitar, the way he stood, his neat suit. Everything about him. He looked older than 22. Something about him seemed permanent, and he filled me with conviction.”

Even though it happened 57 years prior, Dylan remembered the experience of standing a few feet away and making eye contact with Holly like it was yesterday. And of course, he described it exactly as you would expect: Bob Dylan style: “Then, out of the blue, the most uncanny thing happened,” said Dylan. “He looked me right straight dead in the eye, and he transmitted something. Something I didn’t know what. And it gave me the chills.” Three days after locking eyes with his musical idol, Buddy Holly was dead. Holly’s death caused Dylan to reflect on his own mortality at such a young age, stripping away the confidence of youth and beginning the complicated relationship between Dylan and death that would resonate in his songwriting for the rest of his career. Throughout his career, Dylan covered many of Holly’s songs: “Gotta Travel On,” “Not Fade Away,” “Heartbeat,” and others.

On his 1997 triple Grammy-winning album Time Out of Mind Dylan sings “When the last rays of daylight go down / Buddy, you’re old no more” on “Standing in the Doorway.” Dylan said he could feel the late rocker’s presence while making the album. In a 1999 interview, Dylan said, “I don’t really recall exactly what I said about Buddy Holly, but while we were recording, every place I turned there was Buddy Holly. It was one of those things. Every place you turned. You walked down a hallway and you heard Buddy Holly records like ‘That’ll Be the Day.’ Then you’d get in the car to go over to the studio and ‘Rave On’ would be playing. Then you’d walk into this studio and someone’s playing a cassette of ‘It’s So Easy.’” Dylan continued, “And this would happen day after day after day. Phrases of Buddy Holly songs would just come out of nowhere. It was spooky, but after we recorded and left, it stayed in our minds. Well, Buddy Holly’s spirit must have been someplace, hastening this record.” When it won Album of the Year in 1998, Dylan said, “I just have some sort of feeling that he [Holly] was, I don’t know how or why, but I know he was with us all the time we were making this record in some kind of way.”

Dylan later described what happened a day or two after the plane crash when someone gave him a copy of an obscure 12-string guitarist from Louisiana named Huddy Lead Belly. It was of the 1940 song “Cotton Fields” (also known as “In Them Old Cotton Fields Back Home”). Dylan said, “I think it was a day or two after that that his plane went down. And somebody-somebody I’d never seen before-handed me a Leadbelly record with the song ‘Cotton Fields’ on it. And that record changed my life right then and there. Transported me into a world I’d never known. It was like an explosion went off. Like I’d been walking in darkness and all of a sudden the darkness was illuminated. It was like somebody laid hands on me. I must have played that record a hundred times.” Lead Belly led to more influential artists like Robert Johnson, John Lee Hooker, and others in folk and blues, country, and jazz.

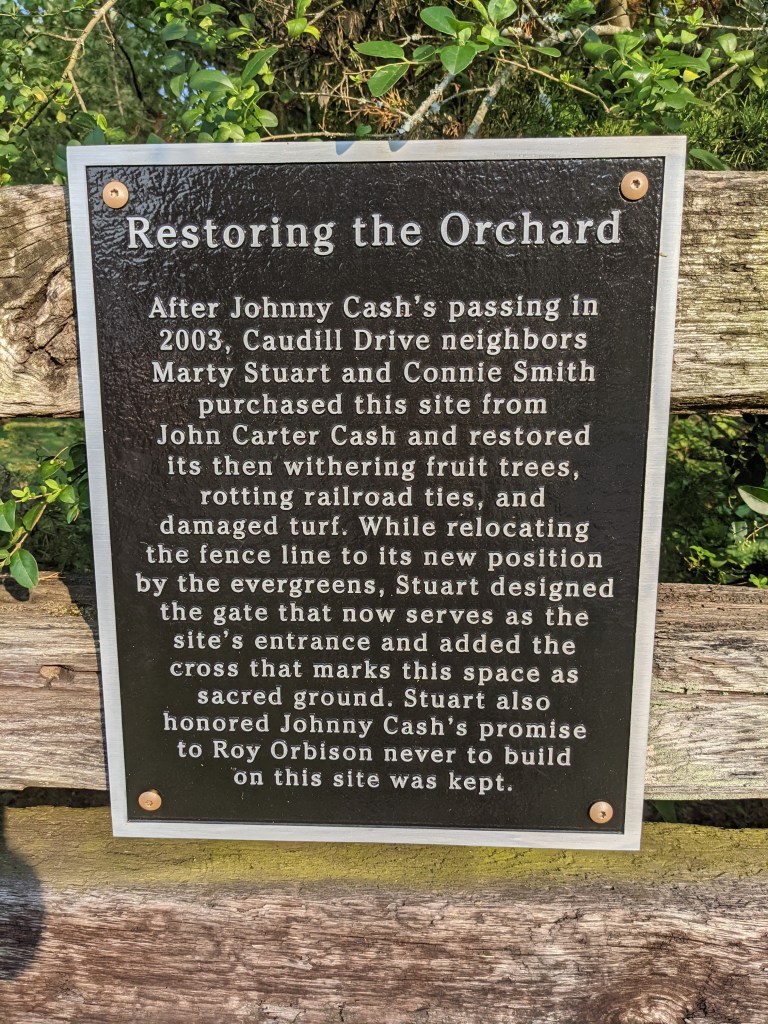

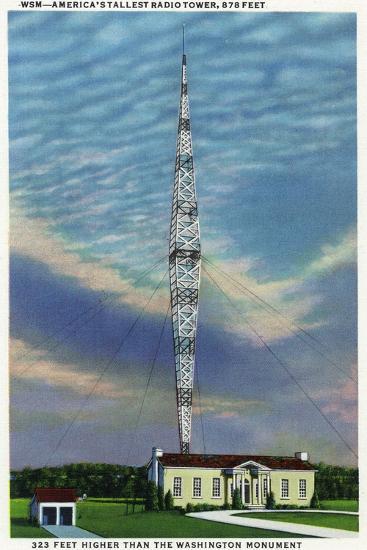

Songwriter Kris Kristofferson once described his friend Johnny Cash as being “a walking contradiction, partly fact, partly fiction” but that verse could easily be applied to Bob Dylan, especially when one considers that Cash was another of Dylan’s acknowledged influences. Over the years, Dylan has acknowledged other influences, and, like Cash, some are more obvious than others. Dylan’s Jewish Russian immigrant parents were fond of the Grand Ole Opry show on WSM radio. WSM broadcasts originated in Brentwood, Tennessee, and featured a unique 808-foot tall “Diamond” shaped tower that allowed the radio station to broadcast to forty states and hundreds of largely rural and small-town audiences. To this day, the WSM Tower is the oldest surviving intact example of this type of radio tower in the world.

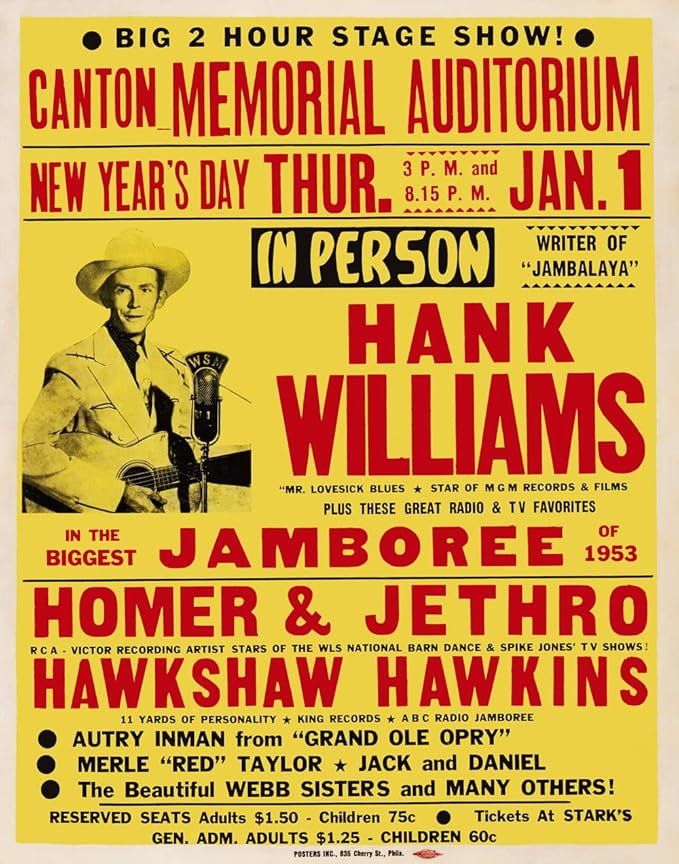

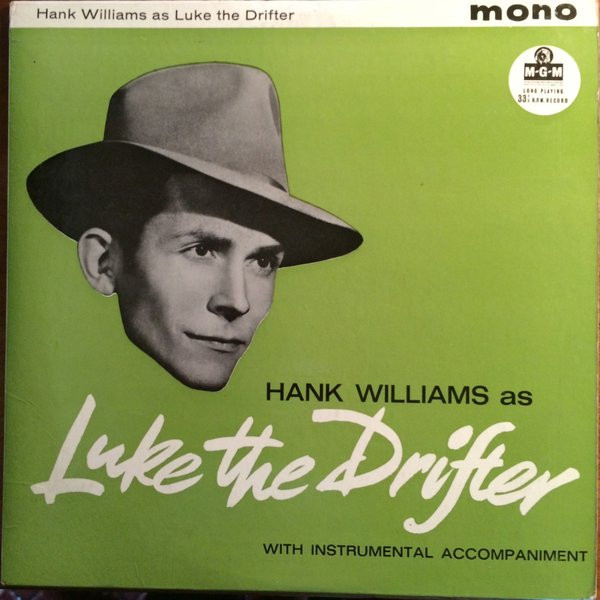

In the early 1950s, Dylan listened to the Grand Ole Opry radio show and heard the songs of Hank Williams for the first time. In his 2004 book, Dylan wrote: “The first time I heard Hank [Williams] he was singing on the Grand Ole Opry…Roy Acuff, who MC’d the program was referred to by the announcer as ‘The King of Country Music.’ Someone would always be introduced as ‘the next governor of Tennessee’ and the show advertised dog food and sold plans for old-age pensions. Hank sang ‘Move It On Over,’ a song about living in the doghouse and it struck me really funny. He also sang spirituals like ‘When God Comes and Gathers His Jewels’ and ‘Are you Walking and a-Talking for the Lord.’ The sound of his voice went through me like an electric rod and I managed to get a hold of a few of his 78s-’Baby We’re Really In Love’ and ‘Honky Tonkin’’ and ‘Lost Highway ‘-and I played them endlessly.”

Dylan continued, “They called him a ‘hillbilly singer,’ but I didn’t know what that was. Homer and Jethro were more like what I thought a hillbilly was. Hank was no burr head. There was nothing clownish about him. Even at a young age, I identified fully with him. I didn’t have to experience anything that Hank did to know what he was singing about. I’d never seen a robin weep, but could imagine it and it made me sad. When he sang ‘the news is out all over town,’ I knew what news that was, even though I didn’t know. The first chance I got, I was going to go to the dance and wear out my shoes too. I’d learn later that Hank had died in the backseat of a car on New Year’s Day, kept my fingers crossed, hoped it wasn’t true. But it was true. It was like a great tree had fallen. Hearing about Hank’s death caught me squarely on the shoulder. The silence of outer space never seemed so loud. Intuitively I knew, though, that his voice would never drop out of sight or fade away-a voice like a beautiful horn.”

“Much later, I’d discover that Hank had been in tremendous pain all of his life, suffered from severe spinal problems-that the pain must have been torturous. In light of that, it’s all the more astonishing to hear his records. It’s almost like he defied the laws of gravity. The Luke the Drifter record, I just about wore out. That’s the one where he sings and recites parables, like the Beatitudes. I could listen to the Luke the Drifter record all day and drift away myself, become totally convinced in the goodness of man. When I hear Hank sing, all movement ceases. The slightest whisper seems sacrilege. In time, I became aware that in Hank’s recorded songs were the archetype rules of poetic songwriting. The architectural forms are like marble pillars and they had to be there. Even his words-all of his syllables are divided up so they make perfect mathematical sense. You can learn a lot about the structure of songwriting by listening to his records, and I listened to them a lot and had them internalized. In a few years’ time, Robert Shelton, the folk and jazz critic for the New York Times, would review one of my performances and would say something like ‘resembling a cross between a choirboy and a beatnik…he breaks all the rules in songwriting, except that of having something to say”. The rules, whether Shelton knew it or not, were Hank’s rules, but it wasn’t like I ever meant to break them. It’s just that what I was trying to express was beyond the circle.”

The Genesis of Bob Dylan, Part 2

Original Publish Date February 27, 2025.

https://weeklyview.net/2025/02/27/the-genesis-of-bob-dylan-part-2/

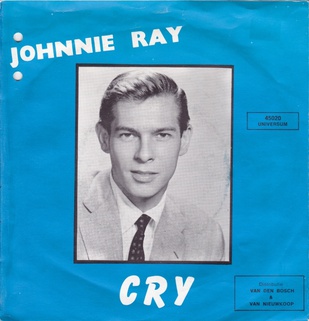

Bob Dylan’s next early musical influence came sandwiched between Hank and Buddy, and it is one you might not expect. Dylan discovered the plaintive delivery of Johnnie Ray (1927-1990) a singer/songwriter who played piano while delivering song lyrics tinged by a stream of tears. Although Ray is largely forgotten today, he was wildly popular for most of the 1950s and has been cited by many artists and critics as a major precursor to rock and roll. Tony Bennett called Ray the “father of rock and roll.” Dylan wrote of Johnnie Ray: “He was the first singer whose voice and style, I guess, I totally fell in love with… I loved his style, wanted to dress like him too.”

Johnnie Ray was a star in a pre-Elvis gyrating world of pop music, a genre of teenaged music that hadn’t existed before World War II. Ray was tall and lanky, partially deaf, and a little awkward on stage, a perceived fragility that caused his songs like “The Little White Cloud That Cried” and “Cry” to soar. Johnnie Ray didn’t just sing these songs-he became them. The press nicknamed him “The Prince of Wails,” “Mr. Emotion,” and “The Nabob of Sob.”

Ray was every bit of an enigma as Bob Dylan. He was an alcoholic who was loved and admired by the Black community (he began his career by performing in segregated Black nightclubs in the 1950s) and a man who never really divulged his sexuality. He was married to a woman in 1952/separated in 1953/divorced in 1954 and was allegedly the father of a child with journalist and What’s My Line TV show panelist Dorothy Kilgallen (1913-1965). In 1951, and again in 1956, Johnnie was arrested and briefly jailed for soliciting a plain-clothed police officer, both times in Detroit. Ray pled guilty to both charges, paid the fine, and was released. Ray was later arrested in a gay bar but the charges were kept quiet.

Sadly, Johnnie found no place in the folk music phenomenon, the rock ‘n’ roll revolution passed him by, and the British Invasion killed all the “white bread” acts, even though Ringo Starr admitted that, in the early days of The Beatles, they only loved “Chuck Berry, Little Richard, and Johnnie Ray.” Oh, there were movie roles, starring alongside Marilyn Monroe in 1954’s There’s No Business Like Show Business, but only fans in the UK and Australia stood by him. During the ’60s and ’70s, Ray made occasional television appearances, but he was largely a forgotten man. Although today, it should be said that Johnnie is mentioned in a Billy Idol song, featured in the opening lines of “Come On Eileen” by Dexys Midnight Runners, and as a cultural touchstone in Billy Joel’s “We Didn’t Start The Fire.” Bob Dylan said this of Ray: “He was the first singer whose voice and style, I guess, I totally fell in love with. There was just something about the way he sang ‘When Your Sweetheart Sends A Letter’…that just knocked me out. I loved his style, wanted to dress like him too.”

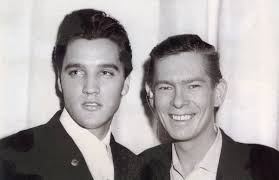

During the fifties, Johnnie Ray went toe-to-toe on the charts with Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Elvis Presley. While the press tried to gin up an imagined feud between Elvis and Johnnie, the two had a mutual respect. After returning to the States from a European tour in 1956, Johnnie Ray was asked “What do you think of Elvis Presley?” He replied, “What’s an Elvis Presley?” People thought he was disrespecting Elvis, but at that point, he had been out of the country and never heard of him. However, Elvis would often sing Johnnie’s songs (like “Such a Night”) through the years. Johnnie Ray bridged the gap between swing and rock n roll and his influence is a huge one. But what about Elvis, was the king of rock n roll an influence on Bob Dylan?

In a 2009 Rolling Stone interview, Dylan said, “I never met Elvis, because I didn’t want to meet Elvis. Elvis was in his Sixties movie period, and he was just crankin’ ’em out and knockin’ ’em off, one after another. And Elvis had kind of fallen out of favor in the Sixties. He didn’t really come back until, whatever was it, ’68? I know the Beatles went to see him, and he just played with their heads…Elvis was truly some sort of American king…And, well, like I said, I wouldn’t quite say he was ridiculed, but close. You see, the music scene had gone past him, and nobody bought his records. Nobody young wanted to listen to him or be like him. Nobody went to see his movies, as far as I know. He just wasn’t in anybody’s mind. Two or three times we were up in Hollywood, and he had sent some of the Memphis Mafia down to where we were to bring us up to see Elvis. But none of us went. Because it seemed like a sorry thing to do. I don’t know if I would have wanted to see Elvis like that. I wanted to see the powerful, mystical Elvis that had crash-landed from a burning star onto American soil. The Elvis that was bursting with life. That’s the Elvis that inspired us to all the possibilities of life. And that Elvis was gone, had left the building.“

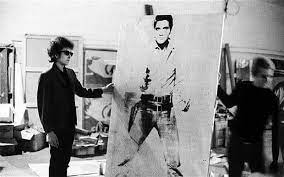

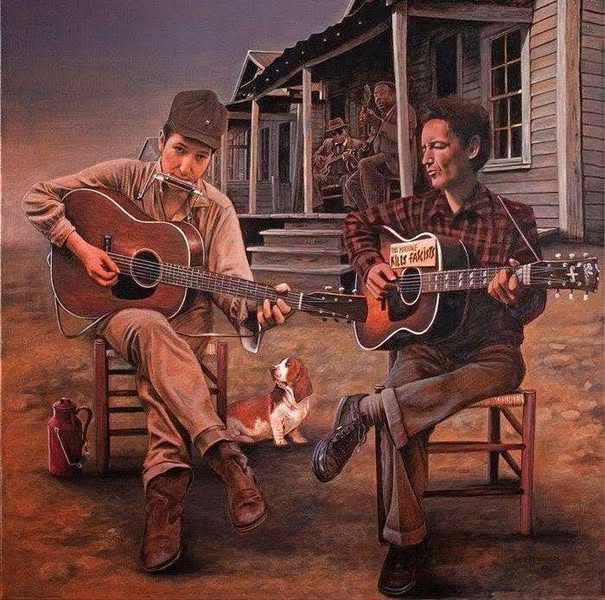

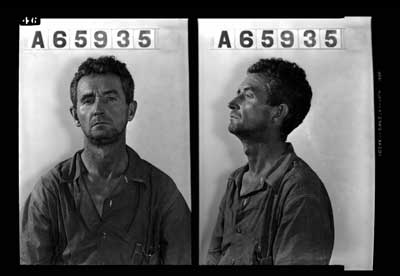

But who was Bob Dylan’s main influence on his musical career? Other than Buddy Holly, it was the only artist that Dylan ever made an effort to find: Woody Guthrie. In May 1960, Dylan dropped out of college and by January 1961, he was performing in coffee houses around Greenwich Village in New York City. Five days after arriving in “The Village,” Dylan tracked Guthrie down at Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital in Morris Plains, New Jersey. In September of 1954, unable to control his muscles, Guthrie checked himself into the facility. He wouldn’t leave for another two years, and when he did so in May 1956, he spent days wandering the streets of Morristown, New Jersey, in a state of homelessness. Guthrie was picked up by police and spent a night in Morris County Jail. It was believed that he was suffering from paranoid schizophrenia and Woody was transferred back to Greystone. It was a voluntary readmission and Greystone staffers could not believe that this drifter had published a book and countless songs. Later Guthrie was diagnosed with Huntington’s disease, a hereditary condition that cause loss of body control.

By the time Bob Dylan met his hero in the winter of 1961, “The Village” was flooded with folk players, and the radio was populated with singers riffing on black artists (Pat Boone’s “Tutti-Fruiti” being the most egregious example) or catchy, but safe, songs from Tin Pan Alley songwriters. This prompted Dylan to comment, “I always kind of wrote my own songs but I never really would play them. Nobody played their own songs, the only person I knew who really did it was Woody Guthrie. Then one day,” he continued, “I just wrote a song, and it was the first song I ever wrote, and it was ‘A Song for Woody Guthrie.’ And I just felt like playing it one night and I played it. I just wanted a song to sing and there came a certain point where I couldn’t sing anything, I had to write what I wanted to sing because what I wanted to sing nobody else was writing, I couldn’t find that song someplace. If I could’ve I probably wouldn’t have ever started writing.” The song would be featured on Dylan’s self-titled debut album, released on March 19, 1962. The album sold 5,000 copies in its first year, just breaking even.

By then, Guthrie’s condition had declined to the point that he could barely move and depending on the day, barely speak. Performing was out of the question. So Dylan sang Woody’s songs back to him and the friendship blossomed. In the novel My Name is New York, Dylan said, “When I met him, he was not functioning with all of his facilities at 100 percent. I was there more as a servant. I knew all of his songs, and I went there to sing him his songs. He always liked the songs. He’d ask for certain ones and I knew them all!” Thereafter, the two shared a unique bond that would last the rest of Guthrie’s life. Dylan wrote of Guthrie’s impact: “The songs themselves had the infinite sweep of humanity in them… [He] was the true voice of the American spirit. I said to myself I was going to be Guthrie’s greatest disciple.” When Guthrie died at age 55 in 1967, Dylan emerged from a self-imposed exile after a motorcycle accident to perform a tribute concert to his hero at Carnegie Hall. According to one biographer, “This farewell to Dylan’s ‘last idol’ was the moment the legacy of American folk was crystalized.”

While any conversations shared between Dylan and Guthrie during those meetings will likely never be known, one Guthrie song is irresistible to not comment on…and speculate. In 1954, Guthrie wrote a song that describes what he felt were the racist housing practices and discriminatory rental policies of his landlord. In December 1950, Guthrie signed a lease at the Beach Haven apartment complex in Gravesend, Brooklyn. The song is called “Old Man Trump” and his landlord was none other than Fred Trump, father of U.S. President Donald Trump. In the song, Guthrie expresses his dissatisfaction with the “color line” Trump had drawn in his Brooklyn neighborhood. Oddly, there are no known Guthrie recordings of this song. However, the lyrics (written in Guthrie’s own hand) were discovered in 2016. “I suppose Old Man Trump knows, Just how much Racial Hate He stirred up In the bloodpot of human hearts When he drawed That color line Here at his Beach Haven family project…Beach Haven is Trump’s Tower, Where no Black folks come to roam. No, no, Old Man Trump! Old Beach Haven ain’t my home!”