Original Publish Date March 21, 2024.

https://weeklyview.net/2024/03/21/abraham-lincoln-the-blood-moon-and-history-part-1/

Indiana is firmly ensnared by “Eclipse Fever,” and for the next few weeks, whether you want to or not, you’re caught smack dab in the middle of the path of totality. Step right up, get your viewing tickets, get your t-shirts, get your eclipse glasses, and start humming Bonnie Tyler’s “Total Eclipse of the Heart,” 24/7. Contrary to what you might think, this is not a modern phenomenon. Eclipses (total or otherwise) have been a staple of American society since the First Crusade’s series of religious wars raged in Jerusalem during the medieval period. Ironically, the First Crusade’s objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Islamic rule. Sound familiar? Well, as Mark Twain once said: “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.”

According to the National Park Service, the first recorded instance of a total eclipse in America can be traced back to July 11, 1097. As evidence, the NPS sites a petroglyph (a symbol carved into rock) in New Mexico’s Chaco National Park. The petroglyph presents a filled-in circle (representing the sun) with wavy lines emanating from its edges with a small, filled-in circle (representing the planet Venus) visible at its upper left. Scientists hypothesize that this would have been the view in that location at the time of the eclipse. The next instance, recorded in 1758 by an amateur astronomer whose name has been lost to history, happened in Rhode Island, making it the first detailed lunar eclipse recorded by a white man in the Americas.

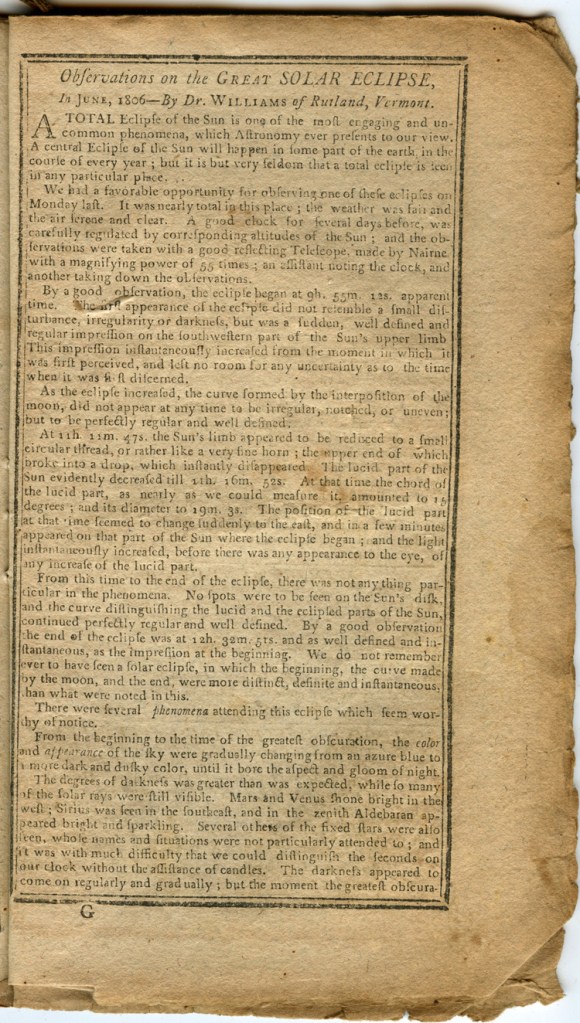

On January 14-15, 1805, Lewis and Clark observed a partial lunar eclipse while at Fort Mandan, North Dakota during their Corps of Discovery Expedition of the newly acquired western portion of the U.S, following the Louisiana Purchase. Unsurprisingly, the explorers eagerly recorded details of that eclipse in their journals including start and stop times. Meriwether Lewis wrote: “Observed an eclips (sic) of the Moon…The commencement of the eclips was obscured by clouds, which continued to interrupt me throughout the whole observation…” A year and a half later, on June 16, 1806, Lewis and Clark observed a solar eclipse while encamped in the Great Pacific Northwest in the path of the total solar eclipse which passed over Arizona, through the Midwest, southern New York State, northern Pennsylvania, and over Boston.

However, far be it from me to assume that eclipse history is notable only from an American point of view. According to NASA “The oldest recorded eclipse in human history may have been on Nov. 30, 3340 B.C.E.” BCE you ask? Well, that means Before Common Era or Before Current Era or Before Christian Era or Before Christ. That is not to say that eclipses were not witnessed by our shared non-white knuckle-dragging ancestors, they just didn’t write it down! Humans struggling through the Stone Ages (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic Eras) surely witnessed eclipses and I suspect that every such occurrence was met with sheer panic. The Vikings believed two wolves would devour the sun or the moon. For the Cherokees, it was a toad. Still, other Native American tribes in northern California believed it was a bear that had swallowed the sun (or moon). Other ancient civilizations believed the Sun was being devoured by planetary monsters: in Siberia, it was a vampire, in Vietnam it was a giant frog, in Argentina it was a jaguar, for indigenous people, and in India and China, it was a dragon. In short, for our pre-Classical Era ancestors, an eclipse meant the world was coming to an end.

Modern research proves that eclipses were recorded in ancient Egypt 4,500 years ago and in China, the Mayan Empire, and Babylonia over 4,000 years old. Chinese legend states that imperial astronomers Hsi and Ho were executed because they failed to predict the total solar eclipse in China on October 22, 2134 BC. Emperor Chung K’ang had the two Royal astronomers “decapitated for having failed to predict an eclipse of the sun which took place while the two delinquents were absent and given to debauchery instead of attending to their duties…Hsi and Ho, drunk with wine, had made no use of their talents. Without regard to the obligations which they owed the Prince, they abandoned the duties of their office…for on the first day of the last moon of Autumn, the sun and moon in their conjunction not being in agreement in Fang, the blind one beat the drum, the mandarins mounted their horses, and the people ran up in haste. At that time, Hsi and Ho, like wooden statues, neither saw nor heard anything and by their negligence in calculating and observing the movement of the stars, they violated the law of death promulgated by our earlier Princes.” The account is important because it proves that astronomers were already able to predict eclipses over four centuries ago.

Lest you think the Chinese were the eclipse bosses, our ancient Irish ancestors were also expert astronomers. Irish star-gazers were carving eclipse images on ancient stone megaliths over 5000 years ago. The Irish were the ones who recorded that November 30th, 3340, BC event, making it the world’s oldest known solar eclipse literally chiseled in stone. The megalith (a very large rough stone used in prehistoric cultures as a monument or building block) is situated at Loughcrew in County Meath. Loughcrew is home to twenty ancient tombs from the 4th millennium BC, the highest point in Meath. The Irish Neolithic priests/astronomers recorded eclipses as seen from that location on 3 stones located there. Leave it to the Celts, who created a “festival of light” to welcome an eclipse, proving that they were capable of predicting them. Ain’t no party like a Celtic party.

A popular eclipse story has worldwide appeal with a splash of American interest. The story of the eclipse that saved Christopher Columbus’ life. In 1503, on what would become his final voyage to the new world, Columbus steered his sinking ships towards Santiago (modern-day Jamaica) with his crews in despair. With most of his anchors lost and his vessels worm-eaten enough to be little more than floating sponges, he beached his ships. Columbus’ glory days were behind him and he now found himself and his crew of 90 men and boys stranded on this desolate Caribbean island. The Italian and his Spaniards were initially welcomed by the indigenous Taíno people but, as time went on, the crew clashed with the natives. Fearing both starvation and conflict, Columbus forbade his crew from leaving their base and tentatively traded Spanish trinkets and jewelry for food and water with the people living there.

The danger was a constant. When investigating Jamaica’s easternmost point. one of his scouting parties was overpowered and captured by hostile locals. In January 1504, some of the crew mutinied, left the base, and spread out onto the island. They abused and mocked the island residents, stole provisions, and “committed every possible excess”, according to one of Columbus’ biographers. The crew had worn out their welcome as tolerance gave way to contempt and hatred. The trade of food and water came to a halt and, facing imminent starvation, Columbus realized that a lunar eclipse was approaching. On March 1, he gathered the chiefs and leaders of the tribal communities, admonished them for withholding provisions, and issued a warning. “The God who protects me will punish you… this very night shall the Moon change her color and lose her light, in testimony of the evils which shall be sent on you from the skies.” The ploy worked and the terrified locals relented, providing food and water once again. In exchange, Columbus promised to perform a rite that would “pardon” them.

Good thing because rescue wouldn’t arrive until June. Thanks to that eclipse, Columbus was able to return to Spain. The remainder of his life was an unhappy story: he returned to Spain in poor physical and mental health and spent his last two years of life lobbying for official recognition and money, which never came. His patrons doubted his mental condition and ignored his demands. He died on May 20, 1506. While lunar eclipses pop up on the pages of history more than solar eclipses for a few different reasons (more people can see them, they last longer, and are visible for more than half the Earth) there was one solar eclipse that did play an important role in U.S. history and it happened right here in pre-statehood Indiana.

In the early 1800s, Shawnee leader Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa (better known as “The Prophet”) were seeking to unite the Native American people and maintain traditional ways. Instead, the governor of the territory, William Henry Harrison (a future U.S. president and grandfather of Indiana’s only homegrown president, Benjamin Harrison) decided that it was a much better idea to persuade tribal leaders to hand over their land or have it taken from them. Knowing that Tecumseh and his Prophet brother held sway over the tribes, Harrison tried to discredit them by asking them for a sign: if the prophet was so powerful, why not ask him to perform a miracle of biblical proportions? Harrison wrote an open letter to the Indians gathered on the Wabash River: “If he is a prophet, ask him to cause the Sun to stand still or the Moon to alter its course, the rivers to cease to flow or the dead to rise from their graves”. Old Tippecanoe’s stunt backfired.

The Prophet agreed and requested that all in the village be assembled for him to deliver his response. He emerged from his wigwam to announce that he had consulted with the Great Spirit and that she was unhappy about Harrison’s request. The Great Spirit agreed to give a sign proving that she and the Prophet were besties. The Prophet spoke in a loud and confident voice saying that: “Fifty days from this day there will be no cloud in the sky. Yet, when the Sun has reached its highest point, at that moment will the Great Spirit take it into her hand and hide it from us. The darkness of night will thereupon cover us and the stars will shine round about us. The birds will roost and the night creatures will awaken and stir.” At noon on June 16th, 1806, The Prophet raised his arms to the sky at just the right time, and a total solar eclipse crossed the region. It was a long eclipse with a band of totality reaching from the southern tip of Lake Michigan to Cincinnati and encompassing most of the lands inhabited by Tenskwatawa’s followers.

The euphoria did not last long. On November 6, Harrison’s forces approached Prophetstown. Accounts are unclear about how the battle began, but Harrison’s sentinels encountered advancing warriors in the pre-dawn hours of November 7. Although slightly outnumbered and low on ammunition, Tenskwatawa’s force of 600 to 700 men attacked Harrison’s soldiers. The attack failed, and after a two-hour engagement that history recalls as the Battle of Tippecanoe, Tenskwatawa’s forces retreated from the field and abandoned Prophetstown to avoid capture. On November 8, Harrison’s army burned the village to the ground. The war would continue for several years and would end only when Tecumseh was killed on October 5, 1813. His prophet brother Tenskwatawa died in November 1836 at his cabin, a site in present-day Kansas City’s Argentine district.

But what about that “Blood Moon” thing in this article’s title? What does that mean? Where did it come from? If you think it sounds Biblical, you’re right. While the Bible doesn’t mention eclipses in particular, there are plenty of verses that can apply. The gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, mention a darkness that lasted three hours after the crucifixion of Jesus, but scientists easily poke holes in those stories. The term originates in the Book of Joel and it designates the blood moon as being a sign of the beginning of the end times: “The sun will turn into darkness, and the moon into blood before the great and terrible day of the Lord comes.” The prophecy is repeated by Peter in Acts during Pentecost, as the fulfillment of Joel’s prophecy. Acts 2:20-38: “The sun shall be turned into darkness, and the moon into blood, before that great and notable day of the Lord.” The blood moon is also prophesied in the Book of Revelation 6:12: “And I beheld when he had opened the sixth seal, and, lo, there was a great earthquake; and the sun became black as sackcloth of hair, and the moon became as blood.” So, ye faithful, the total Solar Eclipse falls on Monday, April 8th this year and if you believe in the prophecy of the blood moon, you’d better be in the pews the day before. Rest easy friends, the blood moon only happens during a Lunar Eclipse. Oh wait, that happens March 25th, so, I guess it still applies. Sounds like the Lunar Eclipse needs a better hype man.

Truth is, the blood moon term is a convenient colloquialism designed to evoke an image simple for people of all races, ages, and religions to understand and to accentuate just how rare and noteworthy total eclipses are. The blood moon happens as the sunlight passes through the earth’s atmosphere and breaks down into several refracted colors from behind the dark of the moon. The scattering of those wavelengths drowns out the blue component of yellow sunlight sending it into the void of space leaving only the red component of light remaining. Contrary to what you may think, the moon is not invisible during a total lunar eclipse but does assume a reddish hue. Despite the ominous connotations, the blood moon is clear proof that the Earth has an atmosphere. The same thing happens at sunrise and sunset as the sunlight travels up or down through the atmosphere, the blue light mostly disappears, leaving the red, orange, and yellow light. Conversely, when the Apollo moonwalkers looked back at the Earth, they saw a dark disk surrounded by a bright, red-hued ring: an eclipse. In short, a blood moon means nothing more than the Moon being eclipsed by the Earth’s shadow.

Centuries of superstition entwined with enigmatic mysticism fuel the interest in eclipses to this day. An eclipse does not discriminate among its viewership. Wealthy or poor, short or tall, male or female, worldly or cloistered, illiterate or learned, anyone and everyone with an interest can witness an eclipse. In the case of Abraham Lincoln, an eclipse in the summer of 1831 would become an early benchmark in the life of the rail-splitter.

Next Week: PART II – Abraham Lincoln, the Blood Moon, and History.

Abraham Lincoln, the Blood Moon, and History.

PART II

Original Publish Date March 28, 2024.

https://weeklyview.net/2024/03/28/abraham-lincoln-the-blood-moon-and-history-part-2/

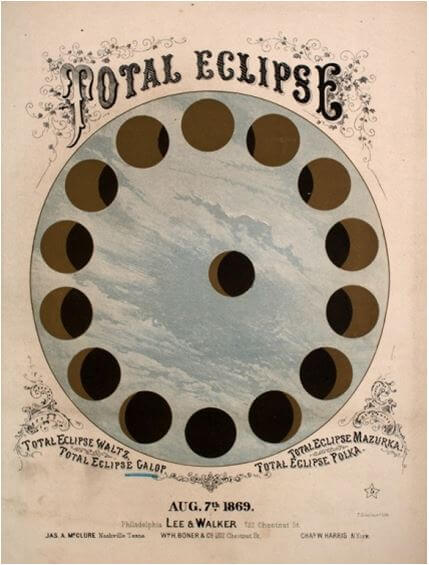

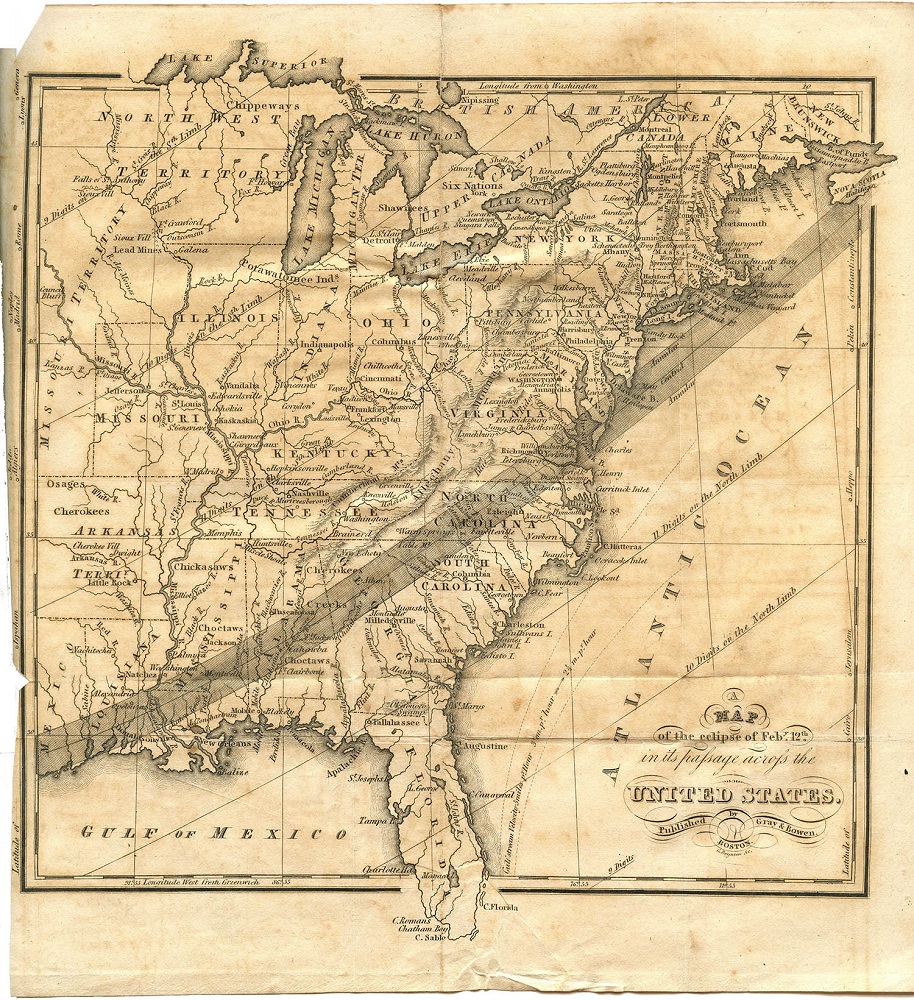

The total eclipse of February 1831 began at 5:21 pm in Cape Cod Massachusetts, swept across the eastern seaboard through Maryland, North and South Carolina, Alabama, and Mississippi, and exited an hour past sunset (6:36 pm) in the Mexico territory that would soon become Texas. The annular solar eclipse (when the Moon passes between the Sun and Earth while it is at its farthest point from Earth) occurred on February 12, 1831. This eclipse is historically important for a few reasons. First, it was the subject of the earliest known eclipse map in the United States, printed in the American Almanac and Repository of Useful Knowledge. Second, it happened on Abraham Lincoln’s twenty-second birthday, and third, because it provided the impetus for Nat Turner’s slave uprising in Virginia. Turner, an enslaved African-American preacher adjudged to be one of the 100 Greatest African Americans by Temple University in 2002, would pay with his life. Lincoln, just over a year after leaving Indiana for Illinois on March 1, 1830, would emancipate Turner’s descendants three decades later and also pay with his life.

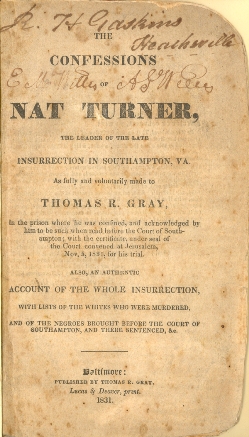

Nat Turner was born into slavery around October 2, 1800, and by his own account, he was born with special powers. In a jailhouse interview published just before he died in 1831, Turner told author Thomas Ruffin Gray for the book The Confessions of Nat Turner that when he was three or four years old, he could provide details of events that occurred before his birth. His mother and other family members believed that Nat was a prophet who was “intended for some great purpose.” Turner learned how to read and write at a young age. He grew up deeply religious and was often seen fasting, praying, or immersed in reading the Bible. Pastor Turner, while preaching to his fellow enslaved people, testified, “To a mind like mine, restless, inquisitive and observant of everything that was passing, it is easy to suppose that religion was the subject to which it would be directed.”

Turner had visions that he interpreted as messages from God, believing that God used the natural world as a backdrop for the placement of omens and signs that guided his life. After Turner witnessed the solar eclipse, he took it as a sign from God to begin an insurrection against slaveholders. Turner, convinced that he was destined for greatness, began preparing for a rebellion against local slaveholders. Nat confessed to author Gray that his divine vision was to avenge slavery and lead his fellow enslaved people from bondage. Turner said the most vivid of those visions came on May 12, 1828, when “I heard a loud noise in the heavens, and the Spirit instantly appeared to me and said the serpent was loosened, and Christ had laid down the yoke he had borne for the sins of men, and that I should take it on and fight against the serpent, for the time was fast approaching when the first should be last and the last should be first.”

Turner purchased muskets and enlisted over seventy freed and enslaved men to his cause. On August 22, 1831, they rebelled and swept through the countryside of Southampton County, Virginia, killing whites and freeing upwards of 75 slaves. By the end of the rebellion, one of the largest slave rebellions in American history, over sixty whites were dead. After it was revealed that Turner and his small band of hatchet-wielding enslaved people had killed his master, Joseph Travis, along with his wife, nine-year-old son, and a hired hand as they slept in their beds, the white citizens became incensed. Then, after it was discovered that two of Turner’s men returned to the Travis home and killed “a little infant sleeping in a cradle” before dumping its body in the fireplace, the die was cast. As a result, over 120 Black people, some of whom had nothing to do with the rebellion, were killed.

Militias were formed and law enforcement was called in to put down the two-day rebellion. Hundreds of federal troops and thousands of militiamen quelled the uprising, capturing most of the participants (except for Turner himself). Nat Turner remained hidden in the woods only a few miles away from the Travis farm for two months. On October 30, 1831, Benjamin Phipps was walking across a nearby farm. He noticed “some brushwood collected in a manner to excite suspicion,” according to a Richmond newspaper, below an overturned pine tree. When Phipps raised his gun, a weak, emaciated Turner emerged from the foxhole, surrendered, and was taken to the Southampton County Jail. Six days after his arrest, he stood trial and was convicted of “conspiring to rebel and making insurrection” and sentenced to death. Turner was hanged from a tree on November 11, 1831. Ironically, his death came in a small town called Jerusalem (present-day Courtland, Virginia). According to many historians, Nat Turner’s revolt contributed to the radicalization of American politics and helped chart the course toward the Civil War.

Equally ironic is that Turner’s revolt brought to an end an embryonic abolitionist movement in Virginia. Following the insurrection, the Virginia legislature narrowly rejected a measure for gradual emancipation that would have followed the lead of the North. About forty petitions, signed by more than 2,000 Virginians, urged the General Assembly to address the troublesome issue of slavery. Some petitions called for outright emancipation, others for repatriation of the enslaved to Africa. Many advocated the removal of free Blacks from the state, seeing them as a nefarious influence. The House established a select committee and the debate finally spilled over into the full body. After vigorous debate, members declined to pass any law. Pro-slavery, anti-abolitionist opinion hardened in Virginia in the years that followed, citing Turner’s intelligence and education as a major cause of the revolt. As a result, measures were passed in Virginia and other southern states making it unlawful to teach enslaved people, or free African Americans for that matter, how to read or write.

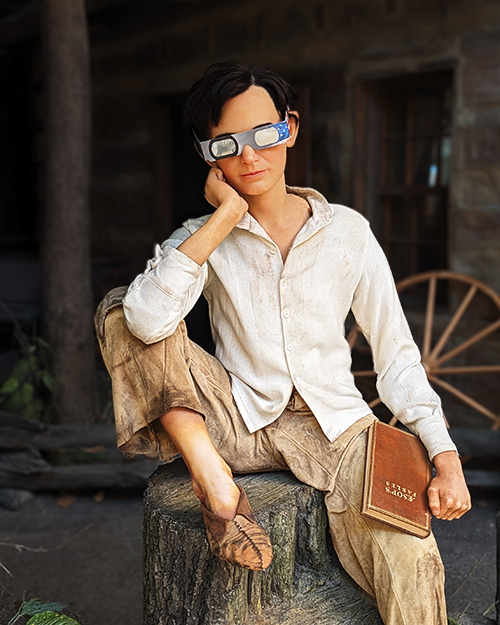

As for Abraham Lincoln, no one knows what the 22-year-old did on his birthday that year. After all, another eclipse, this one a partial eclipse, had occurred over northwest North America at 8:28 pm on Lincoln’s third birthday, February 12, 1812. But for the 1831 total solar eclipse, all that we know for sure is that sometime that year, Lincoln struck out on his own, arriving in New Salem via flatboat and remaining in the village for about six years. The citizens of New Salem first took notice of the lanky fellow when his flatboat became stranded on a nearby milldam in the Sangamon River. A crowd gathered to watch the crew work to free the boat, noticing that Lincoln was obviously in charge. Lincoln directed (and assisted) the other crew members to unload the cargo from the stern which caused the flatboat to free itself from the barrier. Much to the amazement of the gawkers on shore, the flatboat still refused to budge, so Lincoln calmly waded ashore and borrowed an auger from Onstot’s cooper shop. Wading back to the flatboat, auger held high in the sky, Lincoln then drilled a hole in the bow allowing the water to drain out, which caused the flatboat to ease over the dam.

The auger’s owner, Denton Offutt, was so impressed with Lincoln’s handling of the incident, that he offered him a job as a clerk in his store in the flourishing village of New Salem. The store operated from July 1831 to 1832 but the business failed and Offutt moved on. It was at Offutt’s store where the young Lincoln accidentally overcharged a customer six cents (about $1.50 today) and traveled two miles to return the money. Legend states the incident is one of the acts that earned him the nickname “Honest Abe”. It is a great story, but in truth, the fact is that it was Offutt who forced Abe to run those many miles.

One thing is for sure, around the time of the eclipse, Lincoln nearly lost his feet to frostbite. Midwestern Winters can be brutal, especially in February, and the Winter of 1831 in New Salem is remembered as the “deep snow”. According to the book Lincoln Day by Day. A Chronology 1809-1865, in February of 1831, “While crossing Sangamon River, Lincoln breaks through the ice and gets his feet wet. In going two miles to the house of William Warnick he freezes his feet. Mrs. Warnick puts his feet in snow, to take out frostbite, and rubs them with grease.” The “grease” was likely goose grease, skunk oil, or rabbit fat according to the custom of the day. Lincoln recalled the episode with typical humility and humor recalling that he was “comfortably marooned” for weeks in the cabin belonging to Macon County Sheriff William Warnick.

Lincoln was a voracious reader known throughout his young lifetime to travel miles in search of reading material. So, it is at least plausible to imagine that the young rail-splitter may have got ahold of a copy of an American Almanac and Repository of Useful Knowledge to peruse the map of the eclipse found within its pages. Nothing like it had ever been published and it certainly would have been a topic of conversation and focal point of interest by any inquisitive frontier mind.

After all, everyone knew it was coming. The Philadelphia Saturday Bulletin, citing Ash’s Pocket Almanac, proclaimed, “THE GREAT ECLIPSE OF 1831 will be one of the most remarkable to be witnessed in the United States for a long course of years.” Afterward, newspapers proclaimed that “the darkness was such that domestic fowls retired to roost” and “it appeared as if the moon rode unsteadily in her orbit, and the earth seemed to tremble on its axis.” On the day of the eclipse, Americans from the Atlantic seaboard to Galveston Bay cast their eyes toward the heavens in anticipation of this much-ballyhooed celestial event. One diarist saw “men, women, and children … in all directions, with a piece of smoked glass, and eyes turn’d upward.” The Boston Evening Gazette reported that “this part of the world has been all anxiety … to witness the solar eclipse… Business was suspended and thousands of persons were looking at the phenomena with intense curiosity.” “Every person in the city,” noted the Richmond Enquirer, “was star gazing, from bleary-eyed old age to the most bright-eyed infancy.”

The difference with this 1831 was simple. The fears of evil and gloomy predictions of the end of days were mostly absent from big cities. The eclipse was now viewed as a natural atmospheric occurrence aptly explained by science. Rational explanations of atmospheric events, however, offered little solace to many rural Americans. In his book “1831 Year of Eclipse” author Louis P. Masur notes that, “a kind of vague fear, of impending danger-a prophetic presentiment of some approaching catastrophe prevailed” in small towns and “the reasonings of astronomy, or the veritable deductions of mathematical forecast,” did little to diminish the anxiety. One correspondent reported that an “old shoe-black accosted a person in front of our office, the day previous to the eclipse, and asked him if he was not afraid. For, said he, with tears in his eyes, the world is to be destroyed tomorrow; the sun and moon are to meet … and a great earthquake was to swallow us all!—Others said the sun and the earth would come in contact, and the latter would be consumed. Others again, were seen wending their ways to their friends and relations, covered with gloom and sadness; saying that they intended to die with them!”

The day after the eclipse, the world did not end, the sun shone bright again and the eclipse hype subsided. Life returned to normal and newspapers diminished the event, reporting that “The darkness was that of a thunder gust,” and that “The light of the sun was sickly, but shadows were very perceptible.” Edward Everett, a senator from Massachusetts, reported that “a motion was made in the House of Representatives to adjourn over till Monday in consequence of the darkness which was to prevail.” The motion did not pass, and Everett later quipped, “After sitting so frequently when there is darkness inside the House, it would be idle I think to fly before a little darkness on the face of the heavens.” Three decades later, it would be Everett who delivered the speech preceding Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. It would be hard to find two more disparate men in February 1831. Everett in the U.S. Senate and Lincoln on the dirt paths of New Salem, Illinois.

Now understood (and survived) eclipses (Solar, Lunar, and partial) would be better understood by the people experiencing them. Just three years later, another total solar eclipse would cross the U.S. territories from Montana to South Carolina, swooping through parts of the American heartland and the South, on Nov. 30, 1834. While in Springfield, Lincoln experienced another annular solar eclipse on February 12, 1850, his 41st birthday. That event began at 5:54 am and lasted 8 minutes and 35 seconds. If Lincoln witnessed the event, he never noted it. What we do know is on that day, another notable American was experiencing the same celestial event on his own special day. For whenever Lincoln experienced an eclipse on his birthday, so did Charles Darwin. Abraham Lincoln was born on Feb.12, 1809, the same day as Charles Darwin.

Next Week: PART III – Abraham Lincoln, the Blood Moon, and History.

Abraham Lincoln, the Blood Moon, and History.

PART III

Original Publish Date April 4, 2024.

https://weeklyview.net/2024/04/04/abraham-lincoln-the-blood-moon-and-history-part-3/

While rare, total solar eclipses have been a part of life on this planet for centuries. Ironically, if the Solar System had formed differently, they wouldn’t happen at all. While what Hoosiers will witness on April 8th is real, the truth is, it is a bit of an optical illusion. The Sun is 400 times larger than the Moon and we are sitting about 400 times further from the Earth, so while the two appear to be the same size in the sky, it’s merely a coincidence. The Moon does not cover the Sun, it only blocks our sightline, causing the moon’s shadow to fall on the Earth’s surface, resulting in temporary darkness during daylight hours. It is a mesmerizing spectacle that has fascinated humans for centuries.

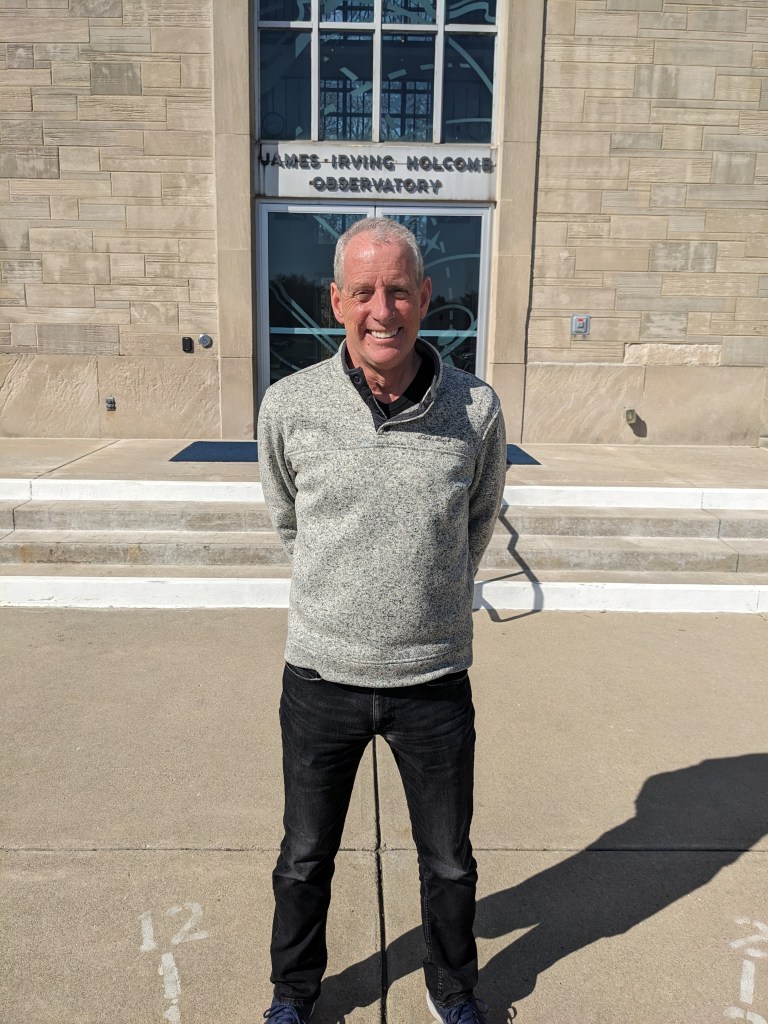

Just how rare is a total solar eclipse? To find the answer, I traveled to the JI Holcomb Observatory and Planetarium on the campus of Butler University in search of Physics & Astronomy Professor Brian Murphy. Murphy, who joined the staff in 1993, has been at Holcomb longer than anyone else on campus. He knows the building like the back of his hand. On Tuesday, March 19, Brian invited me and my trusty photographer Rhonda Hunter to the Observatory for a special behind-the-scenes tour. We were in search of the Irvington connection to this upcoming total eclipse event and Professor Murphy was more than happy to lead the way.

In 1888, Butler College built the school’s first observatory while the campus was still located here in Irvington on the east side of Indianapolis. That observatory housed a 6-inch (150 mm) telescope that was purchased from the estate of Robert McKim of Madison, Indiana that year. McKim, born in County Tyrone Ireland on May 25, 1816 (the year of Indiana statehood), was a stonemason by trade who made his money in real estate. His May 13, 1887, obituary stated that he first landed in Philadelphia before moving to Madison, where, “by industry, frugality, and rapid advance in the price of property, he accumulated a large fortune and expended much of it for the public good…He was in every sense a public benefactor.” He died of Bright’s disease at the age of 71 but not before donating $8,000 for the construction and equipping of a new observatory on the campus of DePauw University. That observatory, built in 1884, became known as McKim Observatory, and it still stands today.

The lens for the Holcomb telescope was manufactured by Alvan Clark & Sons in 1883 and was originally part of McKim’s observatory located near his home in Madison. Alvan Clark & Sons of Cambridgeport, Massachusetts became famous for crafting lenses for some of the largest refracting telescopes in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Five times, the firm built the largest refracting telescopes in the world. When Butler moved to the north side of Indianapolis in 1928, the old observatory on the Irvington campus was torn down. Professor Murphy informs me, “I think the concrete foundation still exists in someone’s backyard in Irvington, although I’ve never seen it.” Steve Barnett, Executive Director at the Irvington Historical Society, delineates by saying, “The foundation of the observatory is in the backyard of 214 S. Butler Avenue.”

While the building was razed, the telescope was saved and removed to the new campus where it was occasionally brought out of storage and placed on the roof of Jordan Hall. The telescope was reconditioned in the 1930s and remounted on the new campus, but sat unused until 1945. In 1953, benefactor James Irving Holcomb (1876-1972) and his wife Sarah (1851-1941) gave $325,000 to construct an observatory as the centennial gift to the university. The couple donated more than $ 4 million to the University in total. Holcomb, who began his business with 25 borrowed dollars as a teenager, sold furniture polish on the streets of Indianapolis. His entrepreneurial hopes were dashed when his bottles of polish exploded in the noonday sun. Thus began a lifetime of interest in Astronomy for JI Holcomb. Along with his philanthropic efforts, Holcomb was a director of the Indiana Lincoln Foundation and the Indiana Lincoln Sesquicentennial Commission.

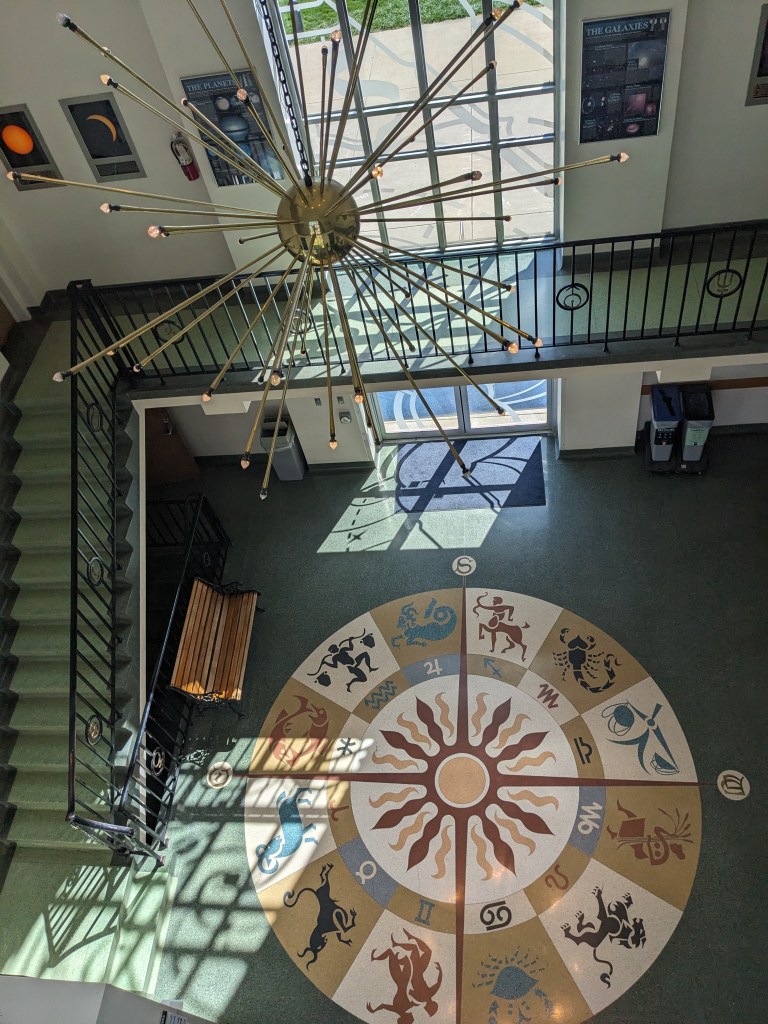

Professor Murphy points out that Holcomb’s shadow still looms large throughout the building. The first thing one notices upon entering is the lobby, the “showplace” of the building, is the 14-foot replica of the zodiac inset in bright colors on the terrazzo floor. A space-age “Sputnik” satellite chandelier dominates the space above the design and strategically placed spotlights enhance the entire appearance of the lobby. A cantilever stairway of 66 steps, also bearing zodiac and planet signs within the iron handrails, winds upward to the dome and telescope. Along the stairway and on the landings are 20 lighted cases containing images from telescopes and spacecraft. The planetarium is both a laboratory and theater, used to examine celestial objects and follow their motions. In addition to the telescope, the observatory has a clock room displaying times from all over the world, a classroom, and, of course, the planetarium. Murphy explains that the designs were perfected by students from the Herron School of Art and Design. Murphy stands in the center of the Zodiac symbol and proclaims, “This is my favorite spot on campus. You can see all the way to the stoplights at 38th Street.” The front door view glides past the greenspaces of the North Mall, Norris Plaza, and the South Mall. Murphy explains, “Mr. Holcomb specifically requested this view as the center of campus.”

I asked about the plans for the upcoming eclipse at Butler. “We’ve canceled classes for the day and expect about 3,000 people to visit. We will close Sunset Avenue in front of the Observatory and will have telescopes set up all over the greenspaces out front for people to look through.” Murphy continues, “We’re free because we are for the public. Park at Hinkle Fieldhouse or in the Clowes Hall garage and walk over. It is a short walk.” He explains, that the observatory will be open that day from noon to nine o’clock, but “We’ll close for awhile before 3:00 so we can all go out and look at the eclipse. We encourage everyone to get outdoors and see it.” Butler has doubled the number of tours for eclipse weekend, “We had 900 people last weekend, so get reservations!” The professor states specifically, “Irvington is in the path of totality. 2017 was the last big deal but it was only a partial eclipse. This is a total solar eclipse. A partial eclipse, even if it is 99%, is nothing like a total eclipse.”

Professor Murphy’s eyes light up as he explains, “Every state will have a partial eclipse, but we are right in the middle of the path of totality. The eclipse will begin around 3:05 pm on April 8, 2024, and it will last about 3 minutes and 45 seconds. We expect to have media from all over the world here including scientists from the National Center for Atmospheric Research from Boulder Colorado.” Murphy is quick to warn, “Do not stare at the sun and absolutely no binoculars! I think everyone knows that, but still. We will have eclipse glasses here for the public for $2 a pair. There will be a big cheer when it first occurs. The only time you can stare at the sun is during totality. Then, take off your glasses for 3 minutes and 45 seconds. You’ll be able to see the Diamond Ring effect in its last stages and the orange glow of the horizon. The temperature will drop 10 degrees, the birds will roost, bugs will chirp, and animals will get confused. We expect to get all of the Chicago people, and I hope a lot of families since Butler has a strict no alcohol policy, we’re very family friendly.”

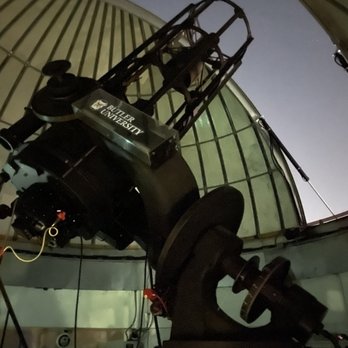

As we ascend the 66 steps up to the observatory, Professor Murphy points out many more of the hidden architectural elements of the building. “It was built in 1953 / 1954 on this hill on the north end of the campus. When I started here in 1993, it was still stuck in the 1950s. Frozen in time. I wanted it to retain its 1950s look but bring it up to date in function.” As we reached the top of the stairway we were encouraged to look down at the mosaic on the floor and see how the lights interact with it. The professor opens the door to the observatory to reveal the gem of the building: the Telescope. Murphy states, “Looks like something out of a 1950s Sci-Fi movie doesn’t it?” And indeed, the apparatus would make any steampunk aficionado drool. The metal dome reveals a triangular aperture that opens and closes at will, spinning towards any celestial waymark one’s heart might desire. In October of 1954, a 38-inch (970 mm) reflecting telescope was installed here by J. W. Fecker, Inc. The telescope was, and still is, the largest in the state of Indiana. Murphy notes, “The observatory’s wooden dome was replaced with its current aluminum dome in the early 1980s. The telescope itself was refurbished in 1995 by AB Engineering of Fort Wayne at a cost of approximately $120,000.”

The giant erector set is topped by two telescopes controlled by 16 or 18 motors and is powered by a $60,000 mirror. The smaller Irvington telescope rides piggyback atop the larger, more modern scope. Murphy states, “For my first five years, I had to spin the telescope around by hand with a crank. Sometime around 1997-98, we reset it to computer ops, everything is automated now.” As he circles the black metal skeleton, Murphy points to a shiny steel bolt that looks oddly out of time, “That was a problem. The original bolt sheared off and we had no idea how to fix it. One of our students went down to Sullivan’s Hardware, picked up a five-dollar bolt, and solved the problem. Sometimes we forget the simple stuff.” Updated, but still ancient-looking celestial charts line the walls of the upper chamber and Murphy assures me they are integral to the operation to this day.

Professor Murphy states with a smile, “Your readers will like to hear that the Irvington lens is in use every night. Since it has a smaller scope, it is used to pinpoint stars and planets for better detail. The lens is worth at least $10,000, but it is always available for use by our guests free of charge.” We make our way back down to the lobby and as we stand on the sunspot mosaic, Murphy reveals a chilling discovery. “I learned that in the late-1970s / early-1980s, the building was scheduled to be torn down and the telescope was to be sold to Ball State University. Luckily that never happened.” Professor Murphy further reveals, “This eclipse will be my last official event here at Butler, I am retiring. My last day is August 15th, 2024.” So with that revelation, I urge all Irvingtonians to make the short trip to the campus observatory and spend a little time with Professor Murphy. When I ask if he will remain connected to the observatory after his retirement, he smiles and replies, “Well, I’m not giving back my keys.”