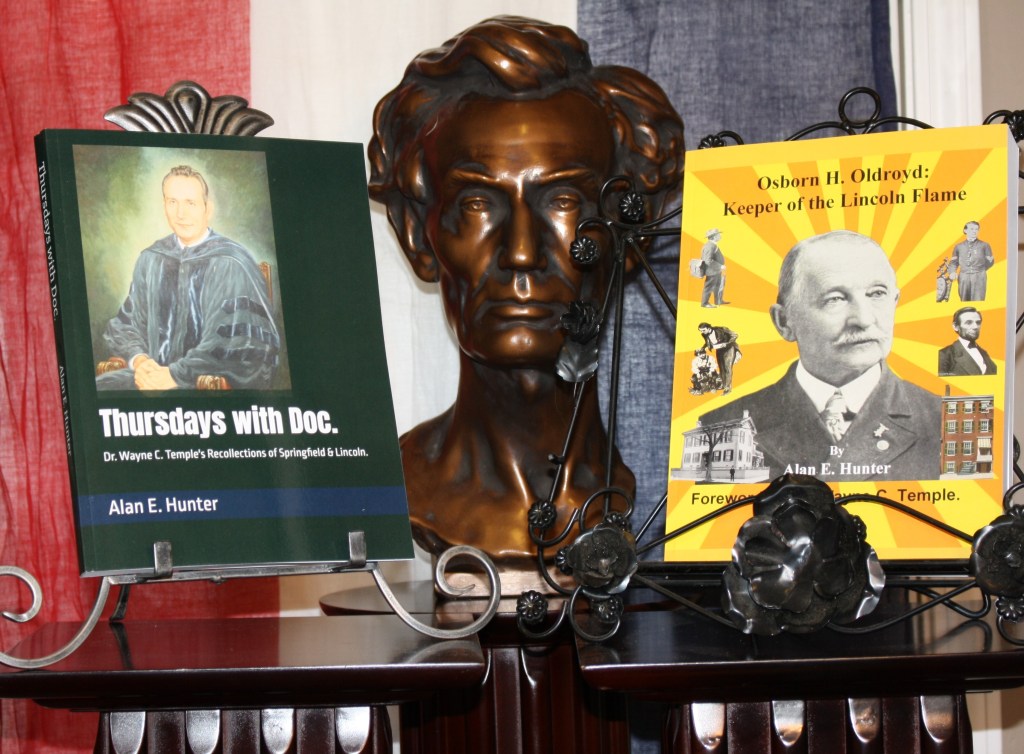

On Sunday, February 16th, 2025, the official book launch for both of my latest books, Thursdays with Doc. Dr. Wayne C. Temple’s Recollections of Springfield & Lincoln and Osborn H. Oldroyd: Keeper of the Lincoln Flame, will be held in Springfield, Illinois. 10:00 am (Central Standard Time) at Books on the Square 427 E. Washington St. Springfield, IL 62701. (217) 965-5443

https://www.booksonthesquare.com/

The author will speak about Doc and Oldroyd, their connection to each other, and Springfield, the day after the Abraham Lincoln 216th Birthday Event: Symposium & Banquet in that historic building across from the Old State Capitol Building where Lincoln served. A book signing will follow the talk. All purchases of Doc’s book that day will include a limited edition, hand-numbered bookplate signed by Doc, Dr. James Cornelius, and the author.

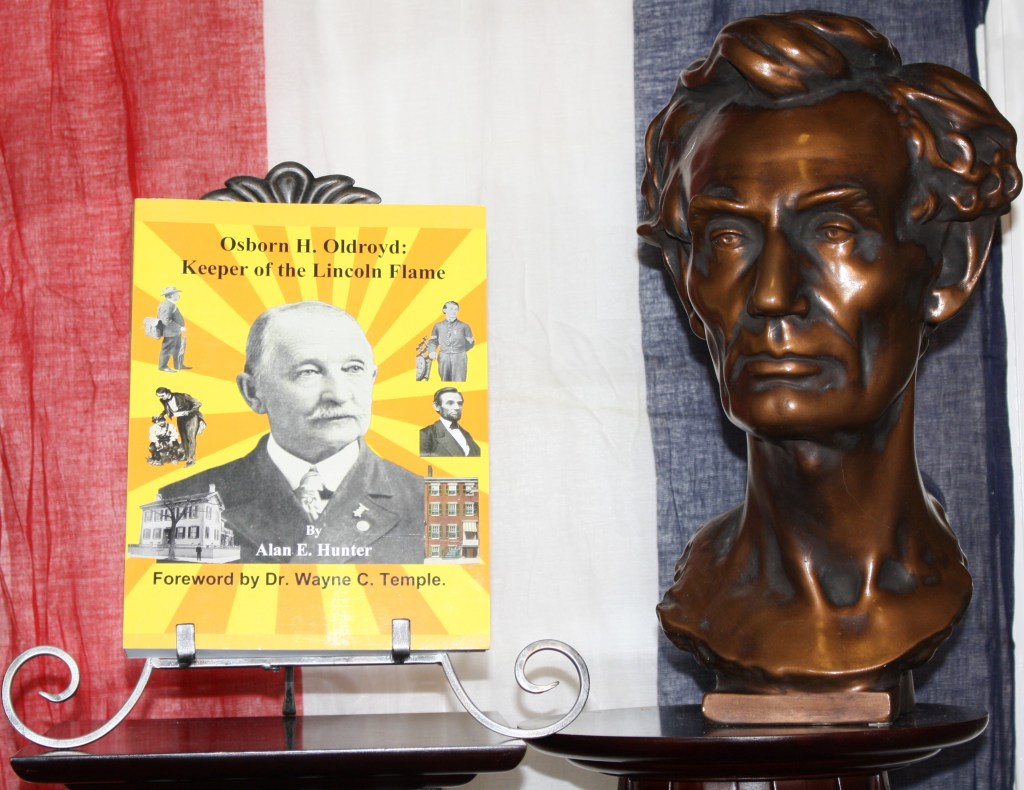

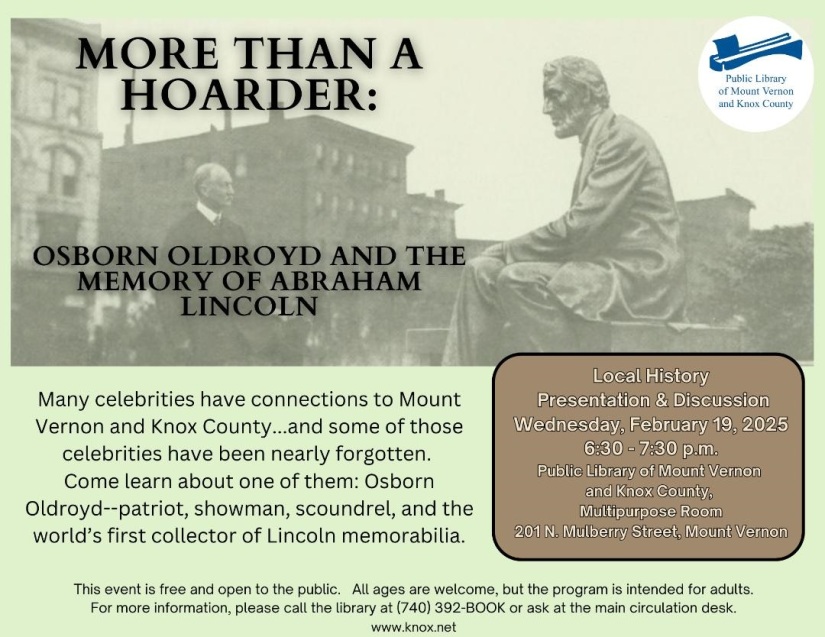

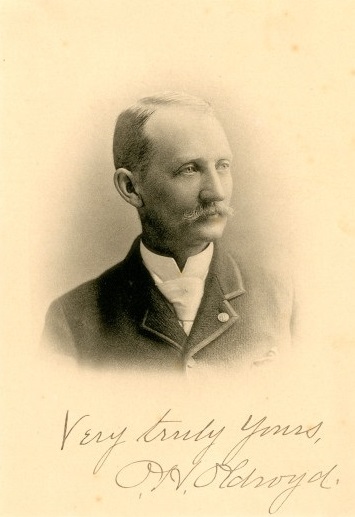

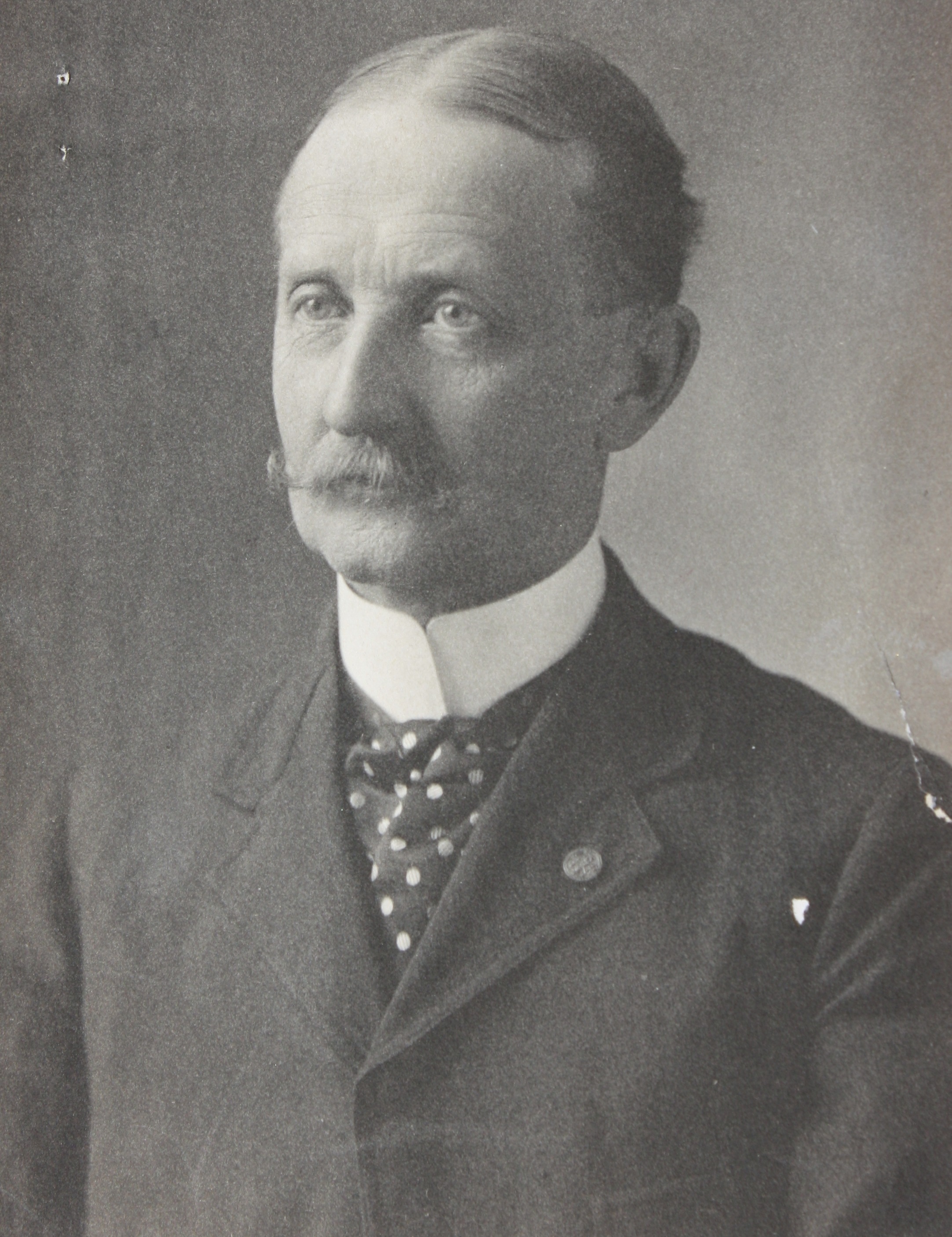

Osborn H. Oldroyd devoted his life to acquiring everything relating to Abraham Lincoln. For nearly half his life, Osborn Oldroyd made his home and displayed his collection in two houses directly associated with the 16th President: the Lincoln Homestead in Springfield, Illinois, and the House Where Lincoln Died in Washington, D.C., a feat that will never be surpassed. Oldroyd guarded a gateway between two worlds. On one side was the world of the now and on the other, the world of the past. When Lincoln passed from life to history, the nation’s grief gave way to reverence; sorrow gave way to esteem. Oldroyd, the loyal log cabin Republican and veteran soldier, did his best to ensure no one forgot. Oldroyd had the institutional memory gained from walking in Lincoln’s footsteps, talking with Lincoln’s contemporaries, and examining the objects associated with his idol. Oldroyd was never trained as a curator. He was a born collector whose experience in handling and researching objects while building his personal collection was his curatorial education. His ability to recount the story behind the object and inject it with enthusiasm, humor, and believability, made him a folk hero to the common man. Just as Oldroyd’s museums can be considered the first of their kind in American museum history, Oldroyd himself can be labeled as America’s first folk curator. To the collection and study of Lincoln, Osborn Oldroyd’s name is unavoidable, particularly in the study of his assassination. It could easily be said that without the efforts of Osborn H. Oldroyd, we may have lost the Lincoln Home in Springfield, the House Where Lincoln Died, and Ford’s Theatre itself. Oldroyd’s obsessive, idiosyncratic devotion to Abraham Lincoln brought the martyred President down from the fog of intellectualism and back to earth for everyone to rediscover in object form. Oldroyd was the last of his kind and the first of another. He arrives by adoration and departs by dedication, opening doors for every Lincoln collector, admirer, and scholar that followed. Born in an age of covered wagons and canals, Oldroyd lived to see the age of the automobile and the airplane. And, thanks mainly to Osborn Oldroyd, visitors to the Petersen house today can walk through the first floor, down the long hallway to stand inside the tiny, dimly-lit otherwise insignificant room with the slanted ceiling where the last, best hope of a nation was lost.

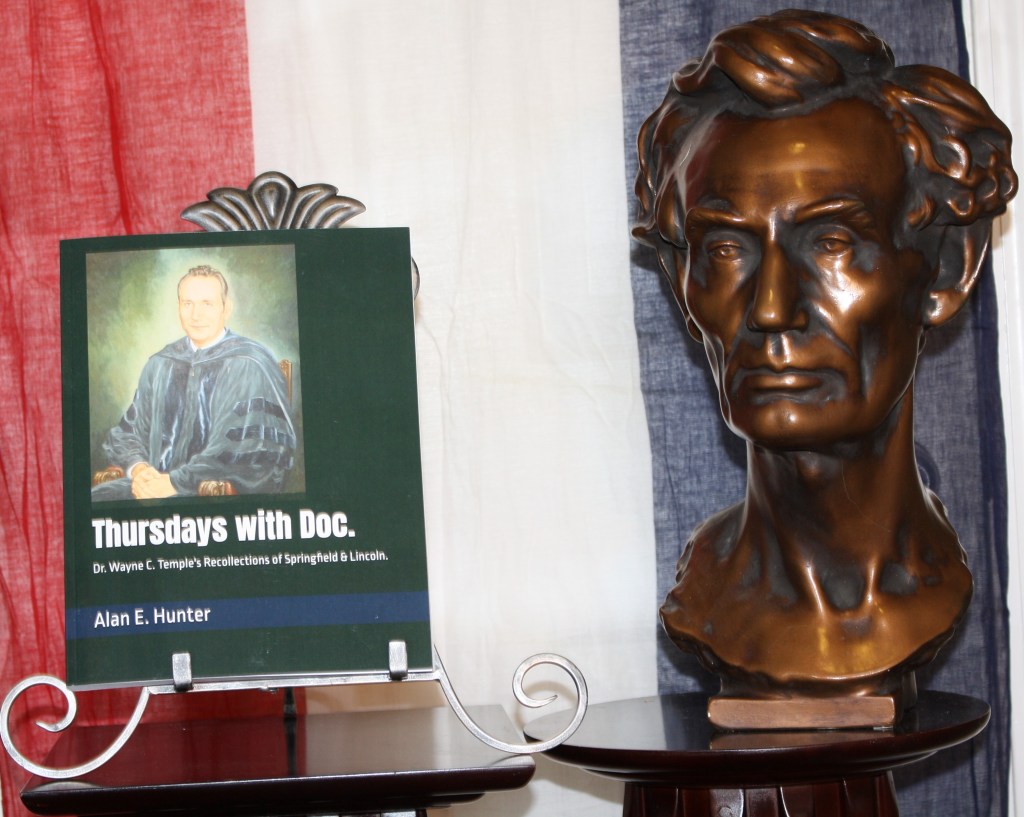

KA series of informal discussions with Springfield Illinois Lincoln scholar and author Dr. Wayne C. Temple, known affectionately as “Doc”. Who, for over 56 years, worked for nine different Illinois Secretaries of State and ten different Governors representing both parties, a remarkable feat of its own. It is a record unlikely to be equaled. Doc was with the Illinois State Archives from 1964 to 2016, much of that time as the Chief Deputy Director. Before that, Doc was editor-in-chief of the Lincoln Herald and in charge of the Dept. of Lincolniana at Lincoln Memorial University in Harrogate, Tennessee from 1958 to 1964, remaining in that position remotely from Springfield until 1973. Doc was an honorary member of the Lincoln Sesquicentennial Commission, 1959-1960, and served on the advisory council of the United States Civil War Centennial Commission, 1960-1966. Doc served in the U.S. Army from 1943 to 1946, and during that time he helped to establish General Dwight D. “Ike” Eisenhower’s communications in Europe. Doc has authored over 20 books, mostly on Lincoln, and has written over 600 articles, poems, reviews, and papers during his career. Doc graduated from the University of Illinois in 1949, studying under his mentor J.G. Randall, the “Dean of Lincoln Scholars.” Doc’s accomplishments are well covered in this volume. This book spans almost three years of interviews with Doc, James Cornelius (former Curator of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum), and author/newspaper columnist Alan E. Hunter. The topics cover Abraham Lincoln, the little-known history and colorful personalities of Springfield, Illinois, the Indigenous Peoples of Illinois, and the life and times of Springfield’s preeminent Lincoln scholar. Now over 100 years old, Dr. Wayne C. Temple has seen it all.

Original publish date: July 6, 2017

Original publish date: July 6, 2017 During his early years in Springfield, he ran a succession of failed businesses. All the while, Oldroyd was moving his family ever closer to the Lincoln Home at Eighth and Jackson Streets. The Oldroyd family first lived at 1101 South Seventh, then 500 South Eighth Street (immediately south of the home), and then, in 1883, when the Lincoln Home became available to rent, Oldroyd moved his family in before the last occupants had completely moved out. At that time, Lincoln’s only surviving son, Robert, owned the home and reluctantly charged Oldroyd $25 per month rent. Contemporary accounts claim that Robert Todd Lincoln agreed to the idea of a museum as long as it was free to the public, a stipulation in place to this day.

During his early years in Springfield, he ran a succession of failed businesses. All the while, Oldroyd was moving his family ever closer to the Lincoln Home at Eighth and Jackson Streets. The Oldroyd family first lived at 1101 South Seventh, then 500 South Eighth Street (immediately south of the home), and then, in 1883, when the Lincoln Home became available to rent, Oldroyd moved his family in before the last occupants had completely moved out. At that time, Lincoln’s only surviving son, Robert, owned the home and reluctantly charged Oldroyd $25 per month rent. Contemporary accounts claim that Robert Todd Lincoln agreed to the idea of a museum as long as it was free to the public, a stipulation in place to this day.

For the next five years “Captain” Oldroyd kept the Lincoln Home and added to his Lincoln collection. At one point, reports claim that Robert Lincoln was furious when Oldroyd allegedly displayed a photograph of John Wilkes Booth in the home, reportedly on the fireplace mantle. Some sources claim that Robert protested and in 1893, when the Illinois state political tides shifted, Oldroyd was unceremoniously ousted as custodian. The new governor put one of his own men into Oldroyd’s former position as political patronage.

For the next five years “Captain” Oldroyd kept the Lincoln Home and added to his Lincoln collection. At one point, reports claim that Robert Lincoln was furious when Oldroyd allegedly displayed a photograph of John Wilkes Booth in the home, reportedly on the fireplace mantle. Some sources claim that Robert protested and in 1893, when the Illinois state political tides shifted, Oldroyd was unceremoniously ousted as custodian. The new governor put one of his own men into Oldroyd’s former position as political patronage.