Original Publish Date February 6, 2025.

https://weeklyview.net/2025/02/06/the-lonesome-death-of-hattie-carroll-part-1/

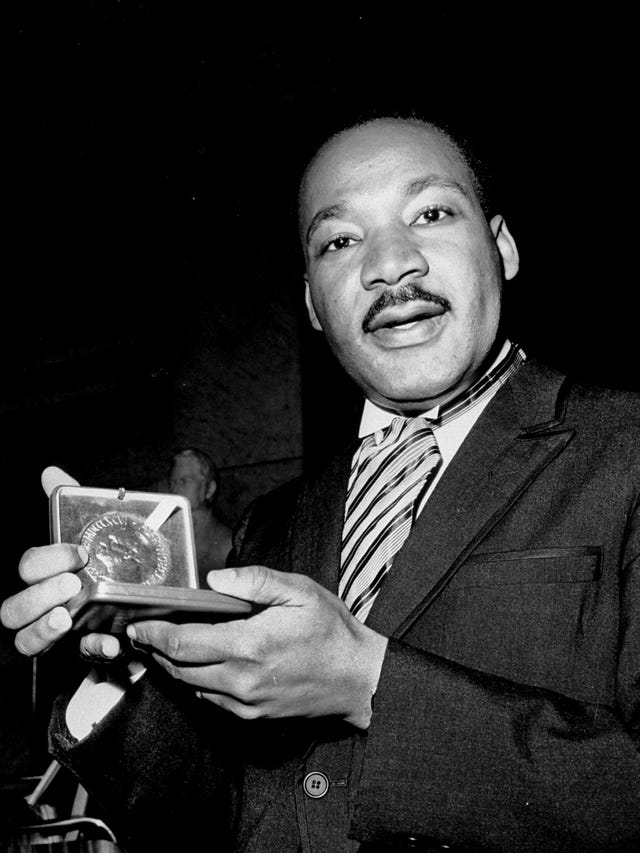

On August 28, 1963, Baptist minister Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech to over 250,000 civil rights supporters during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. In that speech, King called for civil and economic rights and an end to racism in the United States. The speech became the foundation of the civil rights movement and is among the most iconic speeches in American history. Sharing the steps that day was a curly-haired mop-top folk singer named Bob Dylan. This is a story, an insight into the fertile mind of America’s greatest living singer/songwriter. A story most of you have likely never heard.

Born Robert Allen Zimmerman on May 24, 1941, in Duluth, Minnesota, the youngster grew up listening to Hank Williams on the Grand Ole Opry. In his biography, Dylan wrote: “The sound of his voice went through me like an electric rod.” Soon, he began to introduce himself as “Bob Dylan” as an ode to poet Dylan Thomas. In May 1960, Dylan dropped out of the University of Minnesota at the end of his first year. In January 1961, he traveled to New York City in search of his musical idol Woody Guthrie, who was suffering from Huntington’s disease at Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital in New Jersey. As a young man, Dylan read Guthrie’s 1943 autobiography, “Bound for Glory”, and Guthrie quickly became Dylan’s idol and inspiration.

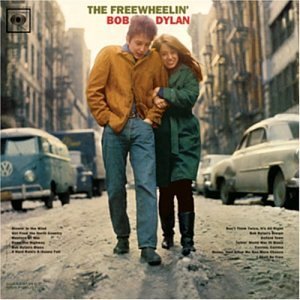

By May 1963, with the release of his second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, the Minnesota folksinger was on the rise as a singer/songwriter. On June 12, 1963, civil rights activist Medgar Evers was assassinated in Jackson, Mississippi. Evers was a veteran U.S. Army soldier who served in a segregated unit during World War II and as the NAACP’s first field secretary in Mississippi. Evers’s death spurred Dylan to write “Only a Pawn in Their Game” about the murder. The song exonerates Evers’s murderer as a poor white man manipulated by race-baiting politicians and the injustices of the social system. At the request of Pete Seeger, Dylan first performed the song at a voter registration rally in Greenwood, Mississippi on July 6, 1963. Two weeks later (August 7) Dylan recorded several takes of the song at Columbia’s studios in New York City, only to select the first take for his album The Times They Are a-Changin’.

Likely at the urging of Pete Seeger, who was busy preparing for a tour of Australia at the time, Dylan, and then-girlfriend Joan Baez, traveled to Washington DC for the March on Washington rally. Of that day, in the 2005 documentary No Direction Home, Dylan recalled, “I looked up from the podium and I thought to myself, ‘I’ve never seen such a large crowd.’ I was up close when King was giving that speech. To this day, it still affects me in a profound way.” On that day, Dylan performed “Only a Pawn in Their Game” and “When the Ship Comes In.” The songs were received with only scattered applause, likely because many marchers did not agree with the sentiments of the song. The famously reflective and observant Dylan walked away from that day contrarily looking inward.

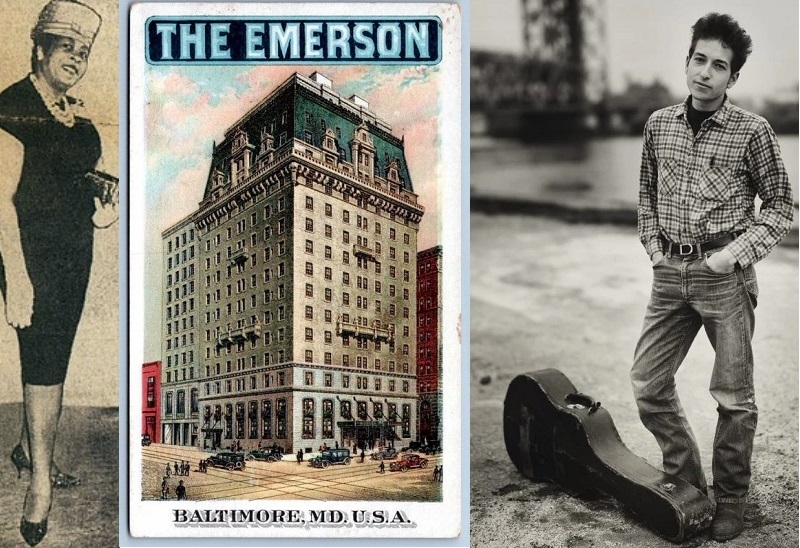

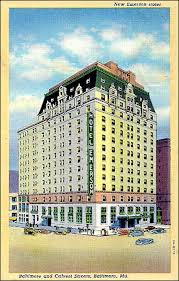

According to a 1991 Washington Post article, while on the journey home to New York City the 22-year-old Dylan read a newspaper article about the conviction of a white man from a wealthy Maryland family named William Devereux “Billy” Zantzinger (1939-2009) for the death of a 51-year-old African-American hotel service worker named Hattie Carroll on February 9, 1963, at the Spinsters’ Ball at the Emerson Hotel in Baltimore, Md. The white tie event was a debutante ball designed to introduce women in their late 20s to the “right” sort of men. The details of the event are just as shocking today as they must have been to Dylan 62 years ago.

On February 8, 1963, 24-year-old Zantzinger attended the event with his father, a former member of the Maryland House of Delegates and the state planning commission who ran one of the most prosperous tobacco operations in Charles County. Before the ball, the Zantzingers stopped for an early dinner and cocktails at downtown Baltimore’s Eager House restaurant. According to witnesses, once at the Spinster’s Ball, a drunken Zantzinger stumbled into the ballroom wearing a tophat with white tie and tails and a carnation in his lapel and carrying a 25-cent wooden toy cane. “I just flew in from Texas! Gimme a drink!” a laughing Billy shouted to the packed crowd of 200 guests. Witnesses said that he was “pretending to be Fred Astaire and when he wanted a drink, he used the cane to tap smartly on the silver punch bowl; when a pretty woman whom he knew waltzed by, he’d tap her playfully, all in fun, no offense, of course.” By 1:30 in the morning, Billy’s mood had darkened and the imposing 6’2″ Zantzinger began to assault hotel workers with his cane, poking and slapping them with it at will. His targets of drunken rage included a bellboy, a waitress, and barmaid Hattie Carroll.

First Zantzinger berated a 30-year-old black employee named Ethel Hill, 30 years old from Belkthune Avenue in Baltimore, with the worst of racial slurs as she was clearing a table near the Zantzingers. Billy asked the young woman about a firemen’s fund, and then, as the police reported it later, she was struck across the buttocks “with a cane of the carnival prize kind.” As she tried to move away, Billy followed her, repeatedly striking her on the arm, thighs, and buttocks. Mrs. Hill wasn’t seriously injured, but her arm hurt, causing her to flee the room in tears.

Next, the cane was used against a bellhop, accentuated with more insults toward the young man, calling him a “Black SOB.” Billy then attacked another employee by yanking the chain around the wine waiter’s neck. When Billy’s 24-year-old wife, Jane, tried to calm him down, he collapsed on top of her in the middle of the dance floor and began hitting her over the head with his shoe. When another guest tried to pull the madman off, Zantzinger thumped him too. Then, temporarily regaining his composure, he stood up and dusted himself off, and the University of Maryland student decided he needed another drink. That is when Zantzinger first encountered Hattie Carroll.

Part II Original Publish Date February 13, 2025.

https://weeklyview.net/2025/02/13/the-lonesome-death-of-hattie-carroll-part-2/

On the night of February 8, 1963, 51-year-old African-American hotel service worker Hattie Carroll was at work behind the bar as an extra employee for special functions and “ballroom events” at the Emerson Hotel in Baltimore, Md. Hattie was active in local social work as a longtime member of the Gillis Memorial Church in that city. The mother of 11 children, Hattie lived with two of her daughters, a 14-year-old and an 18-year-old, her other nine children were all older and married. While a hard worker, she suffered from an enlarged heart and had a history of hypertension.

Zantzinger strode to the bar at a quarter til two and demanded a bourbon and ginger ale. Hattie was busy with another guest when Billy barked out his order. Proud of his prior actions, the drunkard turned his rage on Hattie Carroll whom he accused of not bringing him his bourbon fast enough, again hurling the “N-word” around the room loudly. According to the court transcript, despite the repeated indignations, Hattie replied, “Just a moment sir” and started to prepare his drink. Hattie, now nervous from the berating, fumbled with the glass. Zantzinger shouted, “When I order a drink, I want it now, you black b….!” When Hattie replied that she was hurrying as best she could. Zantzinger again berated her for being too slow and “struck her a hard blow on her shoulder about halfway between the point of her shoulder and her neck.” She shouted for help and slumped against the bar, looking dazed.

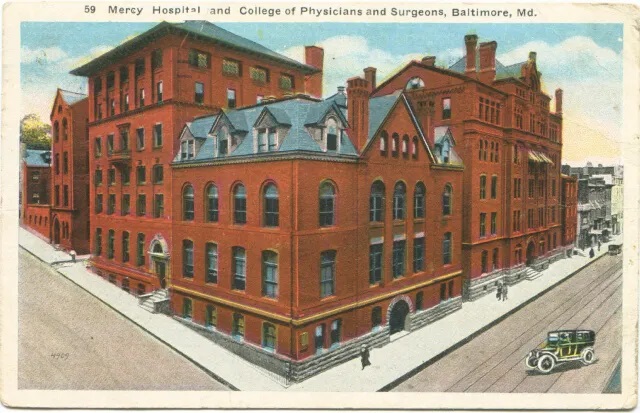

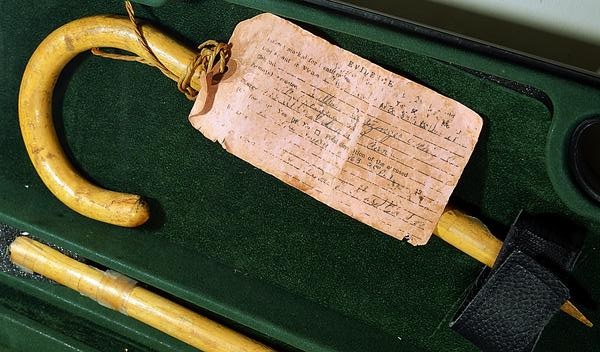

Within five minutes after being struck with the cane, Hattie slumped against another barmaid and said she was feeling sick. Coworkers said that Carroll complained, “I feel deathly ill, that man has upset me so.” Her coworkers helped Hattie to the kitchen. Hattie said her arm had gone numb and her speech became labored just before she collapsed. A hotel official called for an ambulance and the police. The unconscious Hattie Carroll was hospitalized at Mercy Hospital where she died eight hours later at 9 a.m. on February 9, 1963, never having regained consciousness. Her autopsy showed she suffered from hardening of the arteries, an enlarged heart, and high blood pressure. A post-mortem spinal tap confirmed that a brain hemorrhage was the cause of her death. When the wooden cane was found later, it was broken in three places.

Police arrested Zantzinger on the spot for disorderly conduct plus two charges of assault “by striking with a wooden cane.” As they escorted him out through the hotel lobby, the officers were attacked by Zantzinger and his wife. Patrolman Warren Todd received multiple bruises on his legs; Zantzinger received a black eye. Billy Zantzinger spent the rest of those predawn hours in jail, and his wife was released. While Hattie Carroll was taking her last breath, Zantzinger stood in the Central Municipal Court in front of Judge Albert H. Blum, still wearing his white tux and tails, the carnation still in the lapel, though now without his white bow-tie and tophat. Billy pleaded not guilty to the charges and was released on $600 bail. At 9:15 that same morning, Judge Blum was notified of Hattie Carroll’s death. Zantzinger was charged with homicide and a warrant for his re-arrest was issued. It was the first time in the history of the state of Maryland that a white man had been charged with the murder of a black woman.

Zantzinger’s only excuse for these indefensible actions was that he had been extremely drunk and could not remember the attack. His wealthy family retained a top-notch lawyer who managed to get the charges reduced to manslaughter and assault. The trial was moved from Baltimore to the more racially friendly Hagerstown. The attorney proposed that it was the victim’s stress reaction to his client’s verbal and physical abuse that led to the intracranial bleeding, rather than the blunt-force trauma from the blow (that left no physical marks) that killed her. The attorney contended that Hattie was a large, overweight woman with a history of high blood pressure. She could have suffered a fatal stroke at any time. His client was just a victim of circumstances. On August 28, the same day as Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, Zantzinger was convicted on all charges and sentenced to six months’ imprisonment in county jail. With time off for good behavior, he was home in time for Christmas. He was fined $125 for assaulting the other members of the hotel staff.

Upon learning these details, Dylan decided to write a protest song about the case. The song was written in Manhattan while Dylan sat alone in an all-night cafe. The song was “polished” by Dylan at the Carmel, California home of Joan Baez, his then-lover. Nancy Carlin, a friend of Baez who visited the home at the time, recalled: “He would stand in this cubbyhole, beautiful view across the hills, and peck type on an old typewriter…there was an old piano up at Joan’s…and [Dylan would] peck piano playing…up until noon he would drink black coffee then switch over to red wine, quit about five or six.” The result was the song “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll.” It was recorded on October 23, 1963, and quickly incorporated into his live performances. The song was released on February 10, 1964, a year and a day after Zantzinger’s conviction and 61 years ago this week.

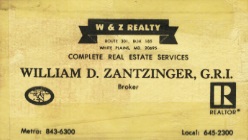

But whatever happened to Billy Zantzinger, the child of white privilege who got away with murder? Zantzinger didn’t have any difficulty at all settling back into Charles County society. He inherited the family tobacco farm which included several “shanties” that he rented to the poor Black population. Billy was a nice fun-loving guy whose neighbors all liked him. But years later, Billy facing financial ruin, began to sell off sections of the 265-acre family estate farm which eventually led him into real estate. He ran a nightclub in La Plata, opened a small weekends-only antique shop, and promoted himself as an appraiser and auctioneer. He was active with the Chamber of Commerce and was elected Chairman of the board of trustees of the Realtors Political Action Committee of Maryland in 1983. Even though Zantzinger ostentatiously drove a Mercedes-Benz sporting a specialized license plate reading “SOLD2U,” the Maryland Terrapin Frat boy quickly got behind in paying his county, state, and federal taxes, both business and personal.

By 1986, the Internal Revenue Service had seized all of his properties. The Washington Post reported that Zantzinger continued to act as landlord of the rental properties on this confiscated land, collecting outrageous amounts of rent for his “shanties” described in the local newspaper as “some beat-up old wooden shacks in Patuxent Woods” even though the hovels had no running water, no toilets, and no heating. Over five years, he collected thousands of dollars from properties he no longer owned. In June of 1991 for his actions, he was charged with “unfair and deceptive trade practices.” After pleading guilty to 50 misdemeanor counts, he was sentenced to 19 months in prison and fined $50,000. A far cry from the six-month sentence and $125 fine in connection with the attack and death of Hattie Carroll 27 years earlier. During sentencing, Zantzinger said, “I never intended to hurt anyone, ever, ever,” Zantzinger said, pleading for leniency; “it’s not my nature.”

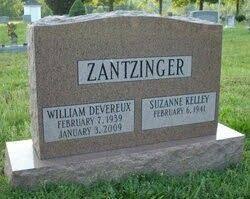

The lasting irony of this story is that William Zantzinger was born on February 7, 1939, almost 25 years to the day of light sentencing for the death of Hattie Carroll. He died on January 3, 2009, just a few days before we as a nation celebrate Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. day every year. Zantzinger is forgotten, barely a footnote in American history while the story of Hattie Carroll will live on forever in Bob Dylan’s song. Hattie’s story is just one of the reasons why Bob Dylan is the greatest American singer/songwriter of all time. Dylan ranks everyone. His earliest idol Hank Williams Sr., known as the “Hillbilly Shakespeare,” would have made a run at Dylan for the title, but Hank checked out way too soon. Dylan has been around for over 60 years (and counting) with an estimated figure of more than 125 million records sold worldwide (and counting). Dylan’s value to music is incalculable. Not only for what Encyclopedia Britannica called his “sophisticated lyrical techniques to the folk music of the early 1960s, infusing it with the intellectualism of classic literature and poetry” but also for his ability to crystalize social issues at the most opportune times in this country’s history.

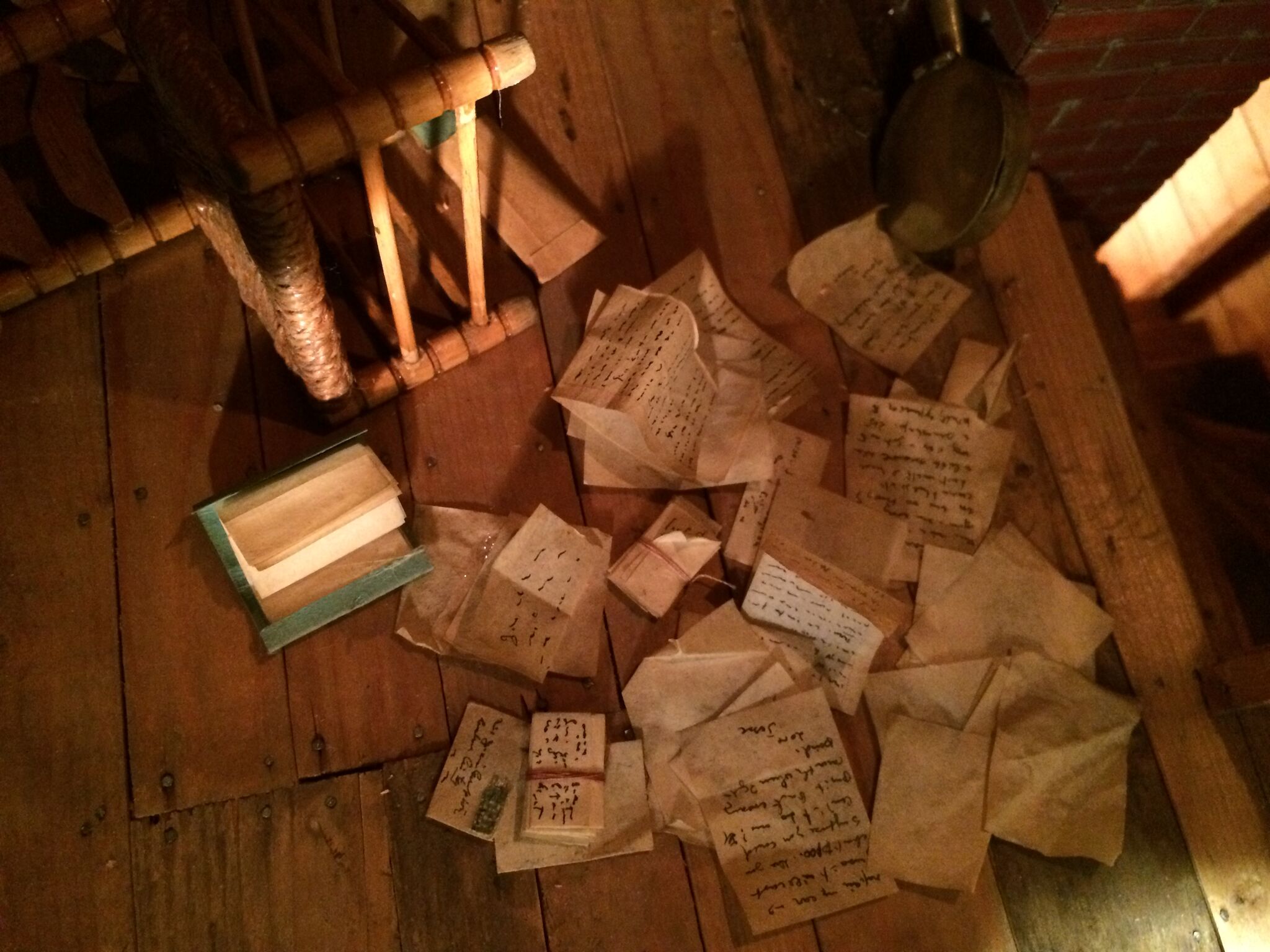

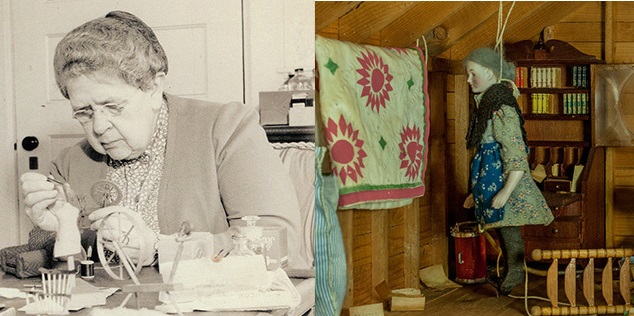

Housed in impressive looking wood and glass locked cases, they are not unlike the ancient penny arcade mechanical machines recalled by every baby boomer’s childhood. Except these scenes are populated by dead bodies, gruesome instruments of death and startling realistic blood spatter patterns. The scenes take place in attics, barns, bedrooms, log cabins, bathrooms, garages, kitchens, parsonages, saloons, jails, porches and even a woodman’s shack. Sometimes, it’s easy to determine the cause of death, but look closer and conclusions are tested. There is more than meets the eye in the Nutshell Studies and any object could be a clue. Every element of the dioramas-angles of minuscule bullet holes, placements of window latches, discoloration of painstakingly painted miniature corpses-challenges the powers of observation and deduction.

Housed in impressive looking wood and glass locked cases, they are not unlike the ancient penny arcade mechanical machines recalled by every baby boomer’s childhood. Except these scenes are populated by dead bodies, gruesome instruments of death and startling realistic blood spatter patterns. The scenes take place in attics, barns, bedrooms, log cabins, bathrooms, garages, kitchens, parsonages, saloons, jails, porches and even a woodman’s shack. Sometimes, it’s easy to determine the cause of death, but look closer and conclusions are tested. There is more than meets the eye in the Nutshell Studies and any object could be a clue. Every element of the dioramas-angles of minuscule bullet holes, placements of window latches, discoloration of painstakingly painted miniature corpses-challenges the powers of observation and deduction. Bruce says, “Look at the miniature sewing machine (about the size of your thumbnail) it’s threaded. There is graffiti on the jail cell walls. The newspapers (less than the size of a postage stamp) are real. Each one had to be printed on a tiny press, the newsprint is immeasurably small. The Life magazine cover is accurate to the week of the crime. The ant-sized cigarettes are hand rolled and burnt on the end. Amazing!” Bruce, who came to the M.E.’s office in 2012, says that although he’s been over every inch of each diorama, he is still making new discoveries.

Bruce says, “Look at the miniature sewing machine (about the size of your thumbnail) it’s threaded. There is graffiti on the jail cell walls. The newspapers (less than the size of a postage stamp) are real. Each one had to be printed on a tiny press, the newsprint is immeasurably small. The Life magazine cover is accurate to the week of the crime. The ant-sized cigarettes are hand rolled and burnt on the end. Amazing!” Bruce, who came to the M.E.’s office in 2012, says that although he’s been over every inch of each diorama, he is still making new discoveries.

The Nutshell Studies made their debut at the homicide seminar in Boston in 1945. It was the first of it’s kind. Bruce says, “Frances’ intention was for Harvard University to do for crime scene investigation what they had done for their famous business school. When Frances died in 1962, support evaporated and by 1966, the department of legal medicine at Harvard was dissolved.” When asked how the displays made the trip from Harvard yard to Baltimore, Bruce states, “That’s a good question. When Harvard planned to throw them away, longtime medical examiner Russell S. Fisher brought them here in 1968. Fisher was a legend and a former student of Frances Glessner Lee. Fisher was one of the doctors called in to examine John F. Kennedy’s head wounds.”

The Nutshell Studies made their debut at the homicide seminar in Boston in 1945. It was the first of it’s kind. Bruce says, “Frances’ intention was for Harvard University to do for crime scene investigation what they had done for their famous business school. When Frances died in 1962, support evaporated and by 1966, the department of legal medicine at Harvard was dissolved.” When asked how the displays made the trip from Harvard yard to Baltimore, Bruce states, “That’s a good question. When Harvard planned to throw them away, longtime medical examiner Russell S. Fisher brought them here in 1968. Fisher was a legend and a former student of Frances Glessner Lee. Fisher was one of the doctors called in to examine John F. Kennedy’s head wounds.”